Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

e-Journal of Portuguese History

versão On-line ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH vol.12 no.2 Porto 2014

ARTICLES

Illegitimate Children and High Society Families in the Social Hierarchies of Portuguese America: Rio de Janeiro, Eighteenth Century

Victor Luiz Alvares Oliveira1

1 Scholarship holder from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico do Brasil (CNPq) and a Masters Degree student of the Programa de Pós Graduação em História Social da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. E-mail: victor.alvares@outlook.com

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the relationship of local high society families in Portuguese America with their children conceived out of wedlock in terms of the inheritances left to the latter in wills. Special attention is given to the case of certain generations of the Sampaio e Almeida family, who belonged to the local high society in colonial Rio de Janeiro. From registers found in Catholic parishes, it was possible to reconstruct the social dynamics of that time, illustrating the agreements that were made and the logic that was involved in the acceptance of illegitimate children within a high society family, while simultaneously discovering the hierarchies that prevailed both within noble families and among the population living on their estates.

Keywords: Illegitimate children; Elites; Families; Rio de Janeiro; Portuguese America.

RESUMO

Este artigo tem como proposta pensar a relação das famílias de elite local da América portuguesa com a sua prole natural e espúria no momento da transmissão testamentária ao atentar para algumas gerações da família Sampaio e Almeida, uma das famílias de elite do Rio de Janeiro colonial. A partir dos registros paroquiais foi possível recuperar as dinâmicas que apontam para os acordos e lógicas envolvidas na aceitação dos filhos naturais dentro de uma família de elite, descortinando as formas como se processavam as hierarquias tanto no interior das famílias senhoriais como também entre a população que vivia nos seus engenhos.

Palavras-chave: Filhos naturais; Elites; Famílias; Rio de Janeiro; América Portuguesa

Among the different characters found in Brazils colonial past, there were certain specific social types that can be said to have emerged quite distinctly and consequently became iconic figures: plantation owners who commanded slaves and dominated large sections of land; devout, submissive women who attended church on Sundays; African slaves who worked in gangs and were engaged in a daily fight for survival; as well as many other characters. As part of the basic practice of their work, historians contribute to the complexity of these stereotypes formed about the people and groups who appeared in the past. As far as colonial high society is concerned, recent research has been very productive in helping to identify the different dynamics that shaped social hierarchies in colonial Brazil.

In the case of Rio de Janeiro, studies of the citys first high society families have identified a close link between certain features from the Ancien Regime and the ethos of the social elite that came to settle in those lands, such as, for instance, the economia de mercês.2 As a region that was initially disputed between the Portuguese and the French, the Portuguese conquest of Rio de Janeiro in the sixteenth century presented certain individuals with the opportunity to render service to the King at the risk of their own lives and those of their men, thus establishing the first families who vied with one another to win the favors granted by the monarch. Furthermore, the revenue and privileges to be gained from holding positions on the city council, and from certain royal offices, placed significant capital in the hands of the first conquerors, and their plantations and farms in Rio de Janeiro initiated the production of sugar cane as early as the sixteenth century. Together with the social and economic privileges that the first conquerors enjoyed access to, the local political sphere was also broadly dominated by this same group of people through the positions that they held in the citys administration. This political and economic culture helped to establish the conquering families as the elite group in Rio de Janeiro during the first centuries of colonization (Fragoso, 2001; 2003).

The favors and lands granted to the first colonizers, however, did not give them jurisdictional rights over the land that they held, nor did the local elite enjoy a legal status that differentiated them from farm workers. Their main distinguishing feature, as the historian Maria Beatriz Nizza da Silva points out, was the fact that they mainly constituted a civil or political nobility, i.e., a nobility who had earned their titles as a reward for the services that they had provided to the Crown, occupying posts in the Church, commanding auxiliary troops, performing administrative duties or even engaging in highly profitable trade. Hence, Silva considers that the process through which individuals were admitted to the ranks of the elite is an important subject of research in the case of the colonial nobility, since their status as nobles frequently did not last, and was not even assured for future generations, as was the case in metropolitan Portugal. Therefore, her study does not provide us with a social portrait of this group, but instead discusses the way in which these individuals rose to the positions that granted them their noble distinction (Silva, 2005).

Nevertheless, studies on the elites of Portuguese America often follow a different path, seeking to understand the reproduction of the social hierarchies that, over several generations, continued to afford the same elite group the social prominence that they had enjoyed since the early days of colonization. Therefore, in addition to the administrative positions or privileges that they attained, it is also important to study the strategies that this group of people adopted in order to affirm their social superiority and subsequently to strengthen their position over time. This line of investigation suggests that the analysis of family behaviors is the best means for understanding the dynamics of elite groups. The strategies and actions adopted by these individuals have begun to be studied in a collective context, with the family now being seen as an entity whose preservation depended on its members, all of which meant that these individuals tended to accept positions and occupations that would help them to enhance their familys status and wealth. Thus, studies of the high society of colonial Brazil have been influenced by the work of Nuno Gonçalo Monteiro and Mafalda Soares da Cunha, who have undertaken valuable research into the nobility in Portugal, illustrating how its members adhered to a model for social reproduction that later served as an example for other elite groups in the Portuguese Empire (Monteiro & Cunha, 2010).

One of the best examples of this trend is the recent study by Manoela Pedroza. While researching the elite families of Campo Grande, a rural parish in Rio de Janeiro, she identified a condition that she refers to as that of an excluído senhorial (someone who was excluded from the right of inheritance) in the social reproduction of such families. Those who found themselves in this condition were children whose rights to inherit their parents estates were struck from their wills. This practice was designed to place the family property undivided and intact into the hands of just one male heir (Pedroza, 2011). Another example comes from Muriel Nazzaris work on the changes that were noted in the dowries offered in colonial São Paulo. As a second-category region in Portuguese America, São Paulo developed an economy based on the capture of the local natives. Nazzari identified the great importance that this practice had in the seventeenth century when forming a dowry to help maintain and reproduce noble families in São Paulo. Dowries were assessed in terms of their capacity to increase the workforce belonging to a family or even to attract fiancés of a higher quality from Europe (Nazzari, 2001). As these two studies show, research into these elite groups has tended to dwell on matters relating to social history in the formation of dowries and in the systems developed for the transfer of property.

The analysis presented in this paper adheres to this line of study. This paper seeks to analyze the relations between a high society family and their illegitimate offspring, focusing on the moment of testamentary transfer. The intention is to discover the dynamics of the involvement of illegitimate children in the family businesses of a local elite over generations, and to explore the way in which these relations gave rise to various social hierarchies. The documentation that will be explored basically consists of wills and baptismal records taken from the parish registers of deaths and baptisms. The place investigated is Nossa Senhora do Loreto de Jacarepaguá, a rural parish in the surroundings of Rio de Janeiro. The analysis follows two main avenues: first, it focuses on the legal provisions governing the status of illegitimate children in matters of inheritance; second, an analysis is made of the actions and strategies adopted in the light of the legislation and social practice in this area. We will therefore be speaking about the rights and limitations established in relation to illegitimate children in theOrdenações Filipinas, the legal code that governed such matters in Portugal and Portuguese America.

Illegitimate children and testamentary transfer

During a long period of the Modern Age, the Ordenações Filipinas regulated the production of wills. In a society that was highly influenced by Catholic Christian theology, the will appeared as a powerful tool for the salvation of the deceased persons soul. One of the main functions of writing a will was to leave pious alms and to organize religious masses for the benefit of the soul of a person that was about to die. Therefore, in contrast to its present-day attention to worldly goods, in the past a will was full of religious and supernatural meaning. Most of the population was entitled to write their own wills. Restrictions were placed on the insane, males younger than 14 and females younger than 12, heretics, and deaf and/or dumb people, among many others. According to the Ordenações, the process was apparently simple: a person went to the public notary with five witnesses over 14 years of age in order to dictate his will, which would be written down by the notary. There was also the closed will, written by the testator himself or, in the event of his being illiterate, written by a third person at the request of the testator. The pages containing the will were presented and confirmed by this person before a notary, who would then notarize it (Almeida, 1870).3

The division of a persons estate among the heirs first took into account the matrimonial condition of the deceased. If this person was married under the system of community property (the most common form of marriage, which consisted of joining together the property of the husband and wife), the spouse that outlived the other received half of the couples estate, while the other half was divided into three parts: two thirds for the necessary heirs (legitimate, illegitimate and legitimized children), while the remaining third was to be spent according to the clauses of the will of the deceased person. This part was commonly known as the third and was usually destined to pay for the expenses incurred with the holding of masses and with donations for the soul of the deceased person. The will actually dealt with the testators property in the third, since this was the only part of his property that the testator could dispose of freely, unless he were single and had no offspring or living ancestors in a position to inherit his estate. In this case, the testator could freely give all of his property to whomsoever he wished.

One thing to bear in mind is that wills could give the false impression that everything they stated would actually happen; yet, the will of the deceased person could only be executed in accordance with the possibilities of his possessions. Another source of information on this subject is to be found in post-mortem inventories written after the persons death. There we find a list of the items belonging to the couple (or the deceased person himself, if single), with the division of this property indicating which heir received what, and also including the costs and expenses incurred with the will itself. Unfortunately, in the case of colonial Rio de Janeiro, especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this type of documentation is very rare; only a few inventories can be found in the National Archives of Rio de Janeiro.

Necessary heirs were basically the children of the deceased; if there were none, then these would become the grandchildren or living ancestors. A priori, only legitimate children born within wedlock were acknowledged as heirs. However, the Ordenações Filipinas had certain loopholes allowing illegitimate children to inherit part of their parents estate. Terms such as bastard and illegitimate were not at all precise, as they concealed a series of categorizations that had different degrees of acceptance as far as inheritances were concerned. Among those who were considered illegitimate were the so-called natural children, born of a single father and mother, or in a situation that involved no impediments in terms of wedlock. These children could inherit property from the father as long as it could be proved that the mother had had sexual intercourse exclusively with the father of the child until it was born, thus giving rise to the status of a legal concubine. If the woman had had several partners prior to the birth of the child, leaving the respective paternity in doubt, then the natural child would not be able to inherit. It was also possible to legitimize natural children through the subsequent marriage of the parents, when neither of them had any legal impediment that prevented them from doing so (Lopes, 1998).

Such natural children represented a lesser scandal in society when compared to spurious children. These were the fruit of damned coitus, i.e. sexual intercourse in which one or both of the people involved were faced with some sort of impediment in terms of wedlock. Children of spurious origin were divided into more specific categories, such as sacrilegious children (when the father or mother was a member of the clergy), adulterous children (when one of those involved was married to another person) and incestuous children (involving relatives by blood, or by marriage of ancestors, up to a distance of four generations). Inheritance was forbidden for such children, and could only take place if the child was recognized by the father. Such affiliation could be acknowledged through a declaration made in the will, although it would still not necessarily guarantee access to the inheritance, since this would only happen if no damage was caused to the legitimate heirs, who could contest the statement made by the father or mother. Another means of legitimizing ones heir was by obtaining letters of legitimization, requested from the Desembargo do Paço, which would then render spurious offspring legitimate. Once the letter was approved, the acknowledged children acquired the right to inherit, but could still face a number of limitations brought about by the inheritance rights of the legitimate children, who should not be damaged in any way, nor be subjected to any form of strife (Lopes, 1998: 167).

The parents duties towards children that were born out of wedlock, as well as the different possibilities existing for the legitimization of such children and their participation in the division of the family estate, have occupied a substantial part of Portuguese American historiography. Yet, one issue that has not yet been afforded much attention is the social status of the father of the child, which also led to differences in the way that the heirs were treated. A recent study by Linda Lewin on the rights of illegitimate children in the inheritance of a family estate focused precisely on this aspect, highlighting the impediments and legal complications that such children of inferior status faced when they were fathered by nobles (Lewin, 2003).

The Ordenações Filipinas determined that natural children fathered by workmen (members of the common people who walked on foot and were neither noblemen nor horsemen) were entitled to be contemplated normally in the division of the inheritance, along with legitimate children. Even the children that a common workman had with his slave woman, should they have been freed on the death of their father or even previously, could be contemplated under normal inheritance procedures. The exclusion of natural children took place only when the father was of a superior status, as theOrdenações clearly stated: If such (natural) children are born, fathered by a horseman, or a squire, or a person of a similar condition, a horseman, and not a common workman who may ride a horse, or a mechanical officer, who is not treated as a common workman, then these children may not inherit, nor take part in the division of property with legitimate children, nor with living legitimate ancestors (Livro 4 – Título XCII, Almeida, 1870).

Even if such an exclusion of natural children could be made dependent on other factors, making it necessary to analyze their existing means in order to perceive their effective involvement in social practice, this privilege for men of distinction opened up the possibility of their placing the family estate at less risk, in the case of children born to their concubines. This prerogative did not remain as an idle legal provision that was never invoked; there are clear signs that frequent attempts were made to implement these clauses in Portuguese America. One such example appears in the will written by Francisco Ferreira Travassos. Deceased in 1737, Travassos had registered his will in the book of deaths in Candelária, one of the main urban parishes of Rio de Janeiro, where he acknowledged a natural daughter he had fathered with the mixed-race woman Ana da Costa when he was still single. Despite not having any legitimate heirs, he states that this daughter is not my heiress, nor should she have any part in my estate, since I am a nobleman, like my father and all my relatives who have served in the Republic of this town and have always lived according to the Law of Nobility, just as I myself have, and I have never parted from it (Deaths of Candelária, 1734-1744, f. 23v). The source of his nobility came from his way of life – possibly displaying symbols of nobility such as a horse and a sword – and the fact that his family normally occupied positions of responsibility in the Republic, probably in this case serving on the city council. In fact, his brother-in-law, who is mentioned in his will, Bartolomeu da Siqueira Cordovil, was in charge of the royal treasury of Rio de Janeiro at that time.

Francisco Ferreira Travassos had no noble title, and did not declare any participation in any military order, nor even, at the time when he wrote his will, did he hold any position on the local council. He was merely a member of a traditional family responsible for the administration of the city, and this was enough to confer upon him the privileges of a nobleman. This explains why the reason that he invoked was of a collective nature, namely that he was a member of a family that belonged to the local nobility, and not one of an individual nature, claiming that he had any privilege or right of his own. What can be noted here is that local families belonging to high society easily met the criteria that recognized them as minimally noble. In addition to occupying positions of local government, it was common for them to also be military officers. According to the ordinances that had originated in the sixteenth century, ranks such as Captain, Ensign, Sergeant and others were intended for those serving in local government, except in the case of towns, villages or councils that were privately ruled by a lord of the manor. For all those who accepted these positions, King Sebastian of Portugalgranted the privilege of their being deemed a horseman and enjoying all the benefits that stemmed from this status (Veríssimo, 1816). Therefore, since the leading families in the various parishes of Rio de Janeiro easily achieved such positions, it was natural for such privileges to be widespread among the local elite.

It is not unusual to find resolutions granting privileges to titled men through a body of legislation that provided for the creation of entailed estates, i.e. leading to instances in which the first-born son was the sole heir to all of his familys possessions. Yet, significantly, this was a title that distinguished the succession of common workmen from that of horsemen, and was awarded to the local nobility of Portuguese America. As far as the division of property was concerned, the Ordenações Filipinas were designed to maintain relative equality between heirs, including even the so-called natural children when these were fathered by commoners. The above-mentioned Título 92 was clearly intended to prevent the illegitimate children of the local high society from becoming yet another element in the division of their wealth, establishing a privilege that, while it was not as powerful as that of entailed estates, at least prevented the number of possible sources for the dispersal of an estate from extending beyond those that were covered by the legislation, namely the legitimate children.

Perhaps the noble families in Portuguese America found it difficult to accept the rights enjoyed by those of inferior status, especially in a context in which it was often just enough to be white among a mass of African slaves, native South Americans, and people of mixed race to consider oneself as different and no longer belonging to the ranks of the common people. Nevertheless, the nobility to be found in South America was basically political in nature, i.e. a nobility that had been acquired through graces and favors bestowed by the Crown, and not as a result of belonging to a certain lineage. This political or landed nobility represented an expansion of the condition of nobility that highlighted the ability of the social organization in the Portuguese-speaking world to adapt to new situations, and demonstrated how the various agents involved did not fit precisely into the old social paradigm of the three medieval orders (Monteiro, 1998: 298-299). Besides those differences that were based on traditional hierarchies, and the fact that certain families retained their prestige and administrative positions on the council due to their earlier contributions in the conquest of the city, there still remained the possibility of being awarded certain privileges in some military order or of occupying certain positions of military command, which conferred the same privileges as those enjoyed by noble knights (Veríssimo, 1816: 21 and 61). More importantly, the social differences to be found in Portuguese-American elites were essentially based on local customs, so that it was not only the titles and prestige conferred by the Crown that guaranteed social distinction for certain families or individuals but also the relationships that these people built up with other smaller hierarchical groups, such as mechanical officers, poor freemen, natives and even slaves, forming clientele networks that sustained their prestige in the eyes of the local society (Fragoso, 2001; Krause, 2014).

While the local power enjoyed by the elites served to reinforce their rights and prerogatives, i.e. through the positions of prestige that they enjoyed or the administrative posts that they held on the city council, the public recognition of the quality and status of certain families was also important, since this meant that they could more easily be granted certain privileges as members of the local nobility (Krause, 2014: 228). An example of this is provided by the aforementioned will of Francisco Ferreira Travassos, who did not want his natural daughter to inherit from him, as he was a noble and his family had always held important positions in the Republic, which, at least in his own mind, had granted him this privilege. It therefore seems that the general definition outlined in Título 92 applied perfectly to tropical noblemen, since it stated that any man who was neither regarded nor treated as a workman could cause his natural children to be excluded from his will. The general tone of this law could easily be applied to the various elite groups that existed in the Portuguese overseas empire. Yet, this still remains more of a hypothesis than a certainty, which points to the need for further research in this area, as it is important for the study of the testamentary transfer systems developed by local elites in the old Portuguese empire.

The line of thought that has been developed so far suggests that the families belonging to the local high society did not need to worry about their natural children, since they could be easily excluded from the division of their estate. However, one question that might be asked is whether it was always worthwhile putting this exclusion into practice. Should illegitimate children be excluded from contact with and acknowledgement by the rest of the family? The analysis that follows of a high society family in colonial Rio de Janeiro, the Sampaio e Almeida family, leads us to think that this situation was of direct importance for the hierarchies and roles existing within a family power strategy, so that such questions represent a useful starting point for analyzing the microcosms of the relationships that existed on a plantation and within a family.

The Sampaio e Almeida family and their illegitimate offspring

The Sampaio e Almeida family settled in Rio de Janeiro after Antônio de Sampaio had provided service to the King, leaving faraway Portugal and crossing the Atlantic Ocean. His own determination or madness had brought him to sixteenth-century Portuguese America. Upon his arrival in Rio de Janeiro in 1567 as an infantry captain, Antônio accompanied the Governor General of Brazil, Mem de Sá, who led a naval expedition to expel what remained of the French invaders in the area. Three years later, Antônio de Sampaio was appointed to the position of ordinary judge in Rio de Janeiro, and, in 1573, was granted three thousand braças (9,156 m2) of land in Paranaguape. He married Maria Coelho, with whom he started the Sampaio e Almeida lineage in South America (Belchior, 1965: 440-441). Thus, lying at the root of this familys history, there were various battles, as well as the appointment to government positions legitimizing their social authority amid a larger group of men who formed the regions first elite.

Like so many others, this family gradually spread across the region of the Atlantic Forest, which became the location of the newly created city: Rio de Janeiro. One of the areas settled by the Portuguese was the parish of Jacarepaguá, where a branch of the Sampaio e Almeida family established itself over several centuries. The boundaries of this region were fixed more precisely in 1661, when the parish dedicated to Our Lady of Loreto (Nossa Senhora de Loreto) and Saint Anthony (Santo Antônio)was founded. The elevation of this geographical area to a parish was a clear acknowledgement of its growing population and economic importance, since, like other rural parishes, Jacarepaguá had a thriving agricultural production based on sugar cane, which was exported through the port of Rio de Janeiro, and the planting of general food crops essential for the survival and trade of the small coastal village. According to a report produced by the government of the Viceroy Marquis de Lavradio (1769-1778), the parish of Jacarepaguá had eight mills producing 156 crates of sugar, and a production of 2,888 bushels of flour, making it one of the largest producers of sugar and flour in that district (Lavradio, 1913 [1779]). At the end of the eighteenth century, in 1797, a chart drawn up of the population and production of that parish confirmed the dominant role of sugar in the economic activities of Jacarepaguá: 9,292 arrobas (136,592.4 kg) were produced that year, 8,938 of which were exported, or, in other words, roughly 96% of the production. Other agricultural products also began to appear, such as rice, beans, corn, flour and coffee, which had similarly significant percentages of exports: 98% of the coffee produced was exported. The same chart provides more precise information about the population of the parish: in 1797, a total of 2,224 people lived there – a figure that included 1,235 slaves, i.e. almost 55% of the total population (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, Rio de Janeiro, Caixa 165, Doc. 62). The few surviving records about that parish show a region that had a slave-worked sugar plantation, although its production is not considered to have been very large when compared with that of other sugar mills, such as the ones in Bahia (Schwartz, 1988).

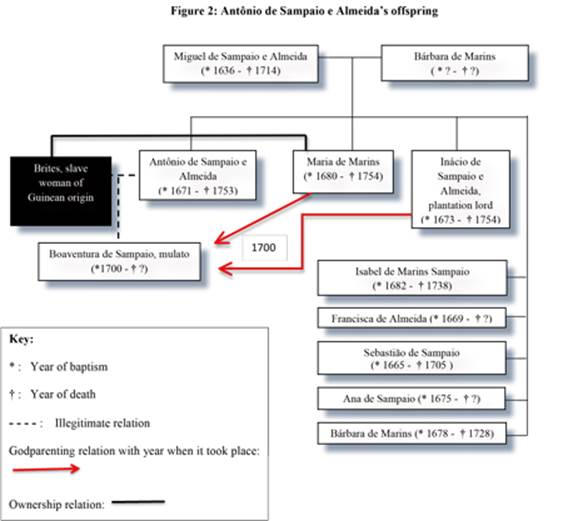

Antônio de Sampaios grandson, Miguel de Sampaio e Almeida, was born, raised, and died in that region. We know a little about his life from the will he wrote before his death in 1714. He married Bárbara de Marins, the daughter of a branch of another of the families that had helped in the conquest of Rio de Janeiro (Rheingantz, 1968), with whom he had eight legitimate children. His offspring were, however, greater in number, since he also had illegitimate children: two natural daughters, Isabel de Sampaio and Maria de Sampaio. Yet, by gathering information from other wills, it was possible to attribute yet more natural daughters to Miguel de Sampaio. Even though they are mentioned in the will, their status is not clearly identified as natural, unlike the other two already mentioned. Figure 1 below details his offspring:

Seven natural daughters, all from the same mother, the black woman Catarina Mendes, and two sons, the name of whose mother is unclear due to the unfortunate deterioration of the document. Nevertheless, Miguel de Sampaio stated that these two men were freemen, since they were born after their mother was officially set free from slavery. Two of his eight legitimate children were already deceased when the father passed away in 1714. One of them, Sebastião de Sampaio, had left children who were, consequently, grandchildren to Miguel de Sampaio and were also his legal heirs. As far as the eventual division of his estate is concerned, which comprised the ample lands in Jacarepaguá and nine slaves, it is difficult to discover how this actually turned out, as the inventory is not available. Still, it is important to highlight that his seven natural daughters were not forgotten: in his will, he left each of them one hundred thousand reais, even stating that part of that amount had already been given to Maria de Sampaio when she married Pedro da Fonseca.

This all indicates that Miguel de Sampaio acknowledged his illegitimate daughters, including them in the division of the third when he awarded them endowments in the form of money. Does this mean that they were legitimized? As stated earlier, at least two of them, Isabel de Sampaio and Maria de Sampaio, are mentioned in the will as his natural daughters. This probably did not bring them legitimacy, since even the testamentary acknowledgement of illegitimate children did not directly lead to legitimization in the case of the offspring of noblemen, making it necessary for the Crown to acknowledge them for these children to be granted rights in the division of assets (Lewin, 2003: 51-52).

Miguel de Sampaio e Almeida had reasons to regard himself as a distinguished person of his time. There is evidence of the services he provided to the city of Rio de Janeiro in a letter written by Antônio de Sampaio e Almeida Marins, Miguel de Sampaios grandson. In that letter, he asks for his rank of Ensign to be confirmed. In order to be awarded this rank, the applicant needed to obtain a certificate from the Rio de Janeiro Council that stated as follows: We certify that Inácio de Sampaio de Almeida, Antônio de Sampaio de Almeida Marins father, is involved in the government of this city and has held in it honorable positions of the Republic, the same role having been fulfilled by Miguel de Sampaio, Antônio de Sampaio de Almeida e Marins paternal grandfather, as well as his maternal grandfather, João Pimenta de Morais. (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, Rio de Janeiro, Caixa 36, Doc. 3.752).

Miguel held positions on the City Council, just as his son Inácio de Sampaio e Almeida would do later on. In addition to this grandson of Miguels, another grandson of his, Manoel Pimenta de Sampaio, also Inácio de Sampaios son, was a military officer in the parish of Jacarepaguá. Hence the prestige of the Sampaio e Almeida family continued to open doors to public positions for its members until, at least, the first half of the eighteenth century, indicating that their families were not commoners in the political context of the city.

Miguel de Sampaio seemed to be a caring father who sought to control the fate of his illegitimate daughters by imposing a condition for the endowments that he left them: these would only take place when each of them married. So, they had to lead their lives in accordance with Christian standards and, for this purpose, he would make them more attractive in the matrimonial market by awarding them an endowment of one hundred thousand reais upon their marriage. Another wish that he expressed in his will was to establish a hierarchy between his legitimate and illegitimate children. Suffice to say that two of his executors (those who made sure his will would be fulfilled) were his legitimate sons: Inácio de Sampaio e Almeida and Antônio de Sampaio e Almeida (cf. Figure 1). Thus, the endowments, while admittedly amounting to financial benefits, ultimately served as a way of perpetuating the relationship of dependence between those who expected to receive the endowments and the legitimate children who had it in their power to grant them. Once more, Miguel de Sampaios own words are highly illustrative: I declare that these alms which I leave to these families will not necessarily come from the residue, as I believe my children will have plenty, since they are left under my sponsorship.

Although they were about to receive endowments, they nonetheless remained in a situation of dependence. If they followed Miguel de Sampaios instructions, they could receive the alms; yet, they would continue under the influence of the Sampaio e Almeida family, as it was due to the latters financial wealth that the illegitimate daughters would be able to arrange a dowry for their marriage that might otherwise be impossible. Such a situation indicates that, even though Miguel de Sampaios illegitimate daughters did not take part in the division of his estate, this does not mean that they were excluded from the family: they would be afforded acknowledgement if they assumed their subordinate position in the family. Further information relating to this aspect can also be found in the will left by João de Sampaio e Almeida, Miguel de Sampaios brother. João de Sampaio died four years after Miguel, in 1718, and, even though he married, he had no legitimate children. Among the executors of his will were his nephews Inácio de Sampaio e Almeida and Antônio de Sampaio e Almeida, Miguel de Sampaios sons. In the division of property that he made with his wife, the following was decided: I declare that I set free, by letter, Catarina, now the wife of Manoel de Fernandes, the father of my goddaughter and niece, albeit natural, as well as her brothers [illegible] and João in order to raise them and to have with me the said family relationship, ( ); and I have brought them into the division of my estate and included this amount in the division of property that I made with my said wife, and no one may interfere with such freed people.

João de Sampaio explicitly stated that Catarina and João were his natural niece and nephew, and that Catarina was his goddaughter. This same Catarina was probably the one that Miguel de Sampaio referred to in his will, to whom he left one hundred thousand reais. She was goddaughter to her uncle and had found a home and a place to grow up in and to have a marriage arranged. In his will, her uncle did not forget his niece, leaving her fifty thousand reais, justified by the acknowledgement and love with which I raised her. The relationship of affection went both ways, as Catarina de Sampaio also asked her uncle to be the godfather to her own daughter, Maria de Sampaio. João de Sampaio showered this goddaughter with presents, leaving her one hundred and fifty thousand reais for a young black girl to be bought and given to her when she got married. He also left her a gold ring with an emerald stone, a gold Saint Benedict chain, two sets of fine-linen embroidered bed sheets, and three silver spoons. A second daughter of Catarina de Sampaio, named Bárbara, also received an endowment of fifty thousand reais.

The family solidarity shown towards natural children thus becomes much clearer. Miguel de Sampaio left some of his natural children to be raised at the house of his brother João de Sampaio, who may have been more of a father figure than Miguel himself. This was also a good option for enjoying access to a safer source of work; after all, João de Sampaio reminds us that he was the one who freed Catarina, João, and another nephew, which means that they came to him first as slaves. Nevertheless, these were slaves of the family, who were raised with love by João himself, as he himself confirms, which certainly distinguished them from the black slaves that came straight from Africa. The family ties and the different treatment that they were given made them more like relatives than slaves, which does not mean that they did not also work.

The acceptance of those illegitimate children into the bosom of the Sampaio e Almeida family was necessarily accompanied by a series of duties. João de Sampaio declared in his will that he was the owner of sugar cane plantations and houses in Irajá, a parish situated to the north of Jacarepaguá, where work was certainly needed and where he may well have raised his brothers children. Those illegitimate children may have been integrated into the family through their work, even if that work was more specialized, and different from the hard physical labor that was reserved for most slaves. João de Sampaio may have been the ideal choice to receive some of Miguels illegitimate children, since he was married, but had no children of his own who would contribute with housework. An exchange of illegitimate children could therefore take place whenever they saw fit. Examples such as this show how important it is to question a childs illegitimacy within a broader perspective rather than to analyze this within the context of the nuclear family itself, i.e. the relationship with the father, mother or siblings alone.

Other illegitimate daughters fathered by Miguel de Sampaio, such as Isabel and Maria de Sampaio, may have lived closer to their father in the parish of Jacarepaguá, and hence may have been the only ones openly recognized as his natural daughters in his will; this information was probably open and public to the local parishioners. In fact, having children outside marriage was not a great outrage according to the standards of the parish of Jacarepaguá. Throughout the second half of the eighteenth century, 18.5% of the children born in that parish were illegitimate, practically all of them originating from relations between freemen and slaves or freedwomen (Venâncio, 1986: 12). As for the black woman Catarina Mendes, who was supposedly the mother of all these natural daughters that Miguel de Sampaio had, only one piece of information was found, provided by the freed man of mixed race João da Costa, his son-in-law, who was married to Isabel de Sampaio (cf. Figure 1). In his will, written in 1711, the year when he died, João da Costa states: I declare that I was born in this city of Rio de Janeiro, the natural son of Gonçalo da Costa and Leonor, a black slave woman belonging to the priest, Father Manoel da Fonseca, and that I am freed and married to Isabel de Sampaio, also freed, the natural daughter of Miguel de Sampaio and Catarina, a black slave woman, belonging to Antônio de Sampaio.

For the first time, Catarina Mendes appears linked to a social condition. Until 1711, at least, she was a black slave woman belonging to Antônio de Sampaio. Miguel de Sampaio had a brother named Antônio de Sampaio e Almeida, who may have been the owner of Catarina Mendes. The problem is that this Antônio de Sampaio died in 1703, so that João da Costa may be referring in the aforementioned fragment of his will to a situation that was already over (Catarina had been a slave) or that was still valid for Antônio de Sampaios heirs (in fact, one of his sons was also called Antônio de Sampaio) (Rheingantz, 1993: 138).

With this piece of information, the story of this romance acquires a more general appearance: Miguel de Sampaio took as his concubine a black slave woman who belonged to one of his brothers and placed some of the offspring she bore him, his illegitimate daughters, to be raised by another brother of his. The rights that Antônio de Sampaio or one of his descendants had over Catarina Mendess offspring, since she was his slave, remained unaltered, as the transfer of her children was made between family members. They had agreements to resolve these cases involving parents, brothers, uncles, nephews and their slaves. This also proves that, besides having the option of abandoning them, high society families could raise such illegitimate children and include them in their family in a hierarchically subordinate role, as Miguel de Sampaio sought to do in his will. One must bear in mind, however, that, even though they had been freed, these illegitimate children would not inherit from the family, due to the Ordenações Filipinas, which prevented them from inheriting from noblemen. In this way, an environment was created that encouraged making such illegitimate children dependent on the goodwill of their relatives and consequently allowed them to be at least contemplated in the third of such wills. Illegitimate children as godparents and the relational world of rural parishes

The relations that these illegitimate children formed in parishes with other people are a very important aspect for understanding how close their interaction could be with other groups in the region. From the analysis of the relationships of god parentage in the case of the illegitimate relatives of the Sampaio e Almeida family, it can be seen that the relations between the aristocratic family and its illegitimate children were frequently more complex than originally seemed to be the case.

Baptizing children, either in large churches in the cities or in small rural chapels, was common practice among the population of colonial Brazil. The widespread nature of the sacrament of Baptism was also of great value to the Catholic Church. The act had wondrous effects, as it meant the remission of all of the sins of baptized people and their consequent integration into the Christian community. Its theological meaning also had social implications, as the parents of baptized children ended up forming spiritual relations with the chosen godparents (Vide, 2010). Hence the choice of godparents was seldom a matter of mere chance, adhering to criteria that were not only based on a relationship of affection between those involved, but were also linked to the interests and alliances that had been established between the godparents and the parents of the baptized child.

The most interesting case seems to be that of Boaventura de Sampaio, the natural son of Antônio de Sampaio e Almeida, Miguel de Sampaios son. This next generation of the family included plantation owners in the parish of Jacarepaguá, such as Inácio de Sampaio e Almeida, Antônios brother, who became the owner of the Rio Grande sugar plantation. Furthermore, Inácio followed in his fathers footsteps and also held positions on the Rio de Janeiro City Council. Some of the Sampaio e Almeida family therefore had a life that revolved around this plantation, which remained in the hands of that family until the early nineteenth century.

Indications left by parish registers clearly point out that Boaventura de Sampaio was Antônio de Sampaio e Almeidas natural son. Antônio married Joana Quaresma, with whom he had no legitimate children, on October 3, 1718. Yet, before that marriage, he had a mulatto son, Boaventura, registered in the book of baptisms of slaves on February 19, 1700. The mother of the child was Brites, a slave of Guinean origin belonging to Maria de Marins, Antônio de Sampaios sister:

Once more, the sins of a family were resolved within it, as he was the son of Antônio de Sampaio and a slave belonging to his sister, Maria de Marins. In addition to owning Boaventura, she was also his godmother and probably helped his mother raise him. The slaves of sisters and brothers seem to have been the preferred consorts of the male members of the Sampaio e Almeida family, as Maria de Marins was not the only one to receive illegitimate nephews. Her sister, Isabel de Marins Sampaio, also went through a similar experience with a woman named Domingas, Isabels slave, who was the mother of two little mulattoes. In her will, Isabel de Marins declared the two of them freed since they were recognized as family, despite her not specifying who their father was.

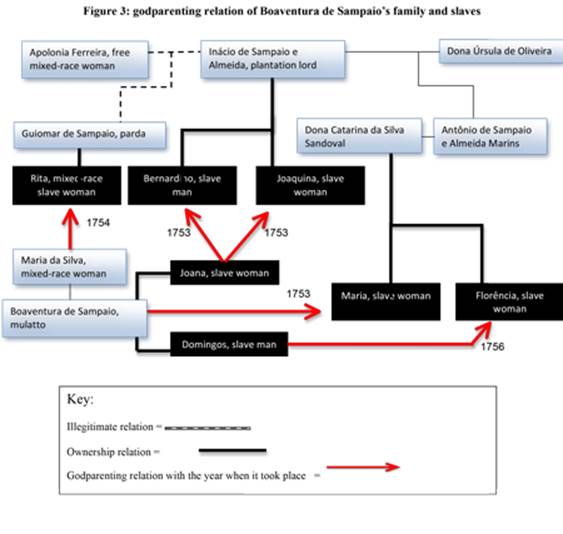

It is most interesting to notice that the Sampaio e Almeida provided godparents for their illegitimate offspring through members of the legitimate family. In addition to his godmother aunt, Boaventura had his other uncle Inácio de Sampaio, the plantation owner, as his godfather. Rather than abandoning their illegitimate children with their slave women, the fathers accepted them into the family from a very early age, linking them to the family through ties that were strengthened through the Catholic rite of godparenting, as seen in the aforementioned case of Catarina de Sampaio, raised by her uncle and godfather, João de Sampaio; and Boaventura de Sampaio, brought up in the house of Maria de Marins, who was also his godmother. They looked after these children with different skin colors and illegitimate origins in the family from early childhood, raising them as family members who were considered inferior within the hierarchy of relatives, but who, nonetheless, were still integrated into their family, through either blood or ritual ties. This ambiguous social position made them valuable intermediaries in the labor field and in relations with other people of inferior status, and they therefore constitute a subject worthy of greater study.

An example of this was the choice of Boaventura de Sampaio as one of the executors of the will of his aunt and godmother, Maria de Marins, who died on September 6, 1754. Maria never married and thus died a spinster, as stated in her will. In her list of endowments, she gave a slave to Francisco da Silva, the son of Boaventura de Sampaio, and left another slave to the same Boaventura, stating: I declare that I leave my slave Miguel to Boaventura de Sampaio, to work for him and to pay with his work for the debts that he knows I owe, and, after paying him, to remain his slave. (...) I declare that I am a partner with Boaventura de Sampaio in a sugar cane business, and my share of this sugar cane I leave to the said Boaventura de Sampaio.

In this case, the inclusion of the illegitimate relations in the Sampaio e Almeida family through work or business is outlined more precisely. For Maria de Marins, this was of great importance, as she had no children and never married, so the formation of a partnership with a nephew of hers in order to run a sugar cane business made good sense. She probably offered him land and some slaves, since she declared five of them in her will, and Boaventura de Sampaio would contribute with his work, running the plantation and its related businesses (note that, in the aforementioned fragment, she states that Boaventura knew about the debts that she had). For her, this relationship with her illegitimate nephew could fill the gap left by the absence of a male figure such as a husband or a son, i.e. Boaventura de Sampaio may have been the link connecting Maria de Marins to the world of business and work, which may not have been accessible to her otherwise, as these were regarded as male prerogatives in colonial Brazil. This situation was also beneficial for Boaventura, who was provided by his family with the necessary resources to develop his plantation and businesses. The fact that he was also appointed as the executor of the wills of Isabel de Marins Sampaio, his other aunt, and of Guiomar de Sampaio, his illegitimate cousin and the natural daughter of Inácio de Sampaio, the plantation owner, who was both uncle and godfather to Boaventura, shows that he was respected by both the legitimate and the illegitimate branches of his family.

Looking at Figure 3 below, it can be seen that the networks that developed around Boaventura de Sampaio and his wife, the mixed-race woman Maria da Silva, were rather complex, even involving his slaves. It can also be seen that his legitimate relatives slaves sought Boaventura de Sampaios slaves or family to be the godparents to their children, showing evident trust and affinity with the family core, which was an illegitimate branch of the aristocratic stem. As previously shown, Boaventura worked on his aunts lands, which were probably located in the Rio Grande plantation, whose owner was his uncle and godfather Inácio de Sampaio e Almeida. There, he probably coordinated the slaves work or performed less tiring work, but it is certain that he functioned as the eyes and ears of both the masters in relation to the slaves and of the slaves in relation to the masters. After all, if he was chosen as the godfather by the slaves, that meant that they looked upon Boaventura to support them in moments of difficulty or tension with their masters.

The Sampaio e Almeida family raised their illegitimate children due to reasons of conscience, and perhaps even as a way of diminishing their guilt in relation to this sin. As these children grew up, they certainly enjoyed more trust from the Sampaio e Almeida family (who gave them responsibility for overseeing part of the plantations and the slaves) than did the foremen from outside the family, who were unrelated to their slaves. Thus, they were able to perform a strategic role if they accepted this subordinate position reserved for them in family businesses. The constant arrival of foreign slaves from Africa and the need to supervise their work brought with it the need for trustworthy communicators. In a way, the Atlantic slave traffic may have encouraged the integration of illegitimate offspring into the bosom of plantation-owning families, since they were accepted and, supposedly, also took interest in developing their businesses.

Conclusion

It is too early to make a precise judgment about the role of illegitimate children in high society families in Portuguese America. Nevertheless, they might be considered to belong to the broader social category of the so-called excluídos senhoriais, as defined by Manoela Pedroza. In such elites, the problem of dividing lands and plantations over various generations was a difficult one, bringing with it serious risks that could weaken the family structure and lead to the break-up of the plantations. So, the elite groups of Rio de Janeiro studied by Pedroza opted to omit some children from the division of property, leaving them with few lands or even with none at all. This did not mean, however, that they were excluded from the family. Many of them lived on the familys plantations, performing small services, working on subsistence smallholdings, or even serving as trusted intermediaries for the plantation owners, who were actually their relatives. Pedroza also points out that it is possible that these relatives who were excluded from the inheritance of the plantation owners estate acted as bridges between the world of the masters and the poor farm workers (Pedroza, 2012: 186-191).

On the other hand, the illegitimate children of elite families, mostly arising from the relations that the lords of the manor had with slave women and free mixed-race women, were therefore born with a legal status that considered them to be hierarchically inferior to a legitimate relative. This is how they appeared to differ from their legitimate relatives who were excluded from the testamentary transfer within their own families: unlike these legitimate relatives, illegitimate children were excluded by specific legislation from inheriting the estate of the prestigious families exerting local power. As a result, they ended up representing an extreme group within the excluídos senhoriais, in terms of testamentary transfer.

However, what initially seemed to be an insurmountable legal exclusion may not have appeared as such in actual social practice. There was a logic behind the acceptance of illegitimate children in prestigious families: the logic of their inclusion in the division of family property arose from their willingness to accept the family hierarchy and the positions dictated by the legitimate relatives. Since these illegitimate children had no legal right to claim any inheritance, they were inclined to be even more obedient of family commands than those legitimate children that were disinherited in the division of property, but who were better placed to make family agreements through which they could obtain other benefits. The respect and obedience that illegitimate children showed to their lineage could entitle them to endowments in family wills, better working and living conditions, and, perhaps, even social ascension.

But what kind of nobility is this that has natural children with slaves and then incorporates them into the familys life? The example of the Sampaio e Almeida family is certainly not a paradigm among elite families in Portuguese America, although recent research describing the nobility in the region of Rio de Janeiro has highlighted the increasing tendency for elite families to have relationships with mixed-race individuals with whom they often shared a family, including mulatto relatives who reached positions of ecclesiastic or military prominence, through the influence of their elite families (Fragoso, 2010; Aguiar, 2012). In fact, the acceptance of natural children was also seen as a valuable asset within that context in which there were vast lands to be occupied and much work to be done, i.e., even though they were natural children, they could be useful for their families by providing some specialized work, serving as intermediaries in business or even occupying those lands, so as to keep them in the family. In this way, they could contribute to the familys material well-being, which was one of the main factors determining the social quality of the family. Thus, for reasons of conscience or even for financial reasons, the exclusion of mixed-race and natural children was not necessarily the norm among all local elite families, even if, legally, they could effectively reject or even disown their natural children.

As previously pointed out, both the use that was made of this legal entitlement that elite families enjoyed to exclude mixed-race and natural children from inheritance and the effectiveness of such a ban is a topic that requires further research through the observation of other cases. Nevertheless, this mechanism may reveal itself to have been one of the key aspects in the reinforcement of the hierarchical relations existing between legitimate and illegitimate relatives within socially acknowledged noble families, thus creating a situation in which relationships of dependence were created between the two sides. It is therefore possible to form a picture that sees illegitimate relatives as enjoying a social condition that extended beyond their particularities as a hierarchically inferior social group, while also reflecting on their role in the formation of hierarchies and the status of an old social elite in Portuguese America.

DOCUMENTATION

Arquivo da Cúria Metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro

Livro de Batismo de Escravos de Jacarepaguá, 1752-1795.

Will and Testament of Isabel de Marins Sampaio, 16/11/1738. Livro de Óbitos de Livres de Jacarepaguá, 1734 – 1796.

Will and Testament of Inácio de Sampaio e Almeida, 28/09/1748. Livro de Óbitos de Livres de Jacarepaguá, 1734 – 1796.

Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino

REQUERIMENTO do alferes de uma das Companhias da Nobreza do Rio de Janeiro, Antônio de Sampaio de Almeida Morais, ao rei [D. João V], solicitando alvará para que os escrivães lhe passassem sua folha de culpas, necessária para poder receber a respectiva carta patente. Rio de Janeiro, 19 de setembro de 1743, Caixa 36, Doc. 3.752, Projeto Resgate (Centro de Memória Digital, Universidade de Brasília, http://www.cmd.unb.br/biblioteca.html)

MAPAS descritivos da população das freguesias de Campo Grande, Jacarepaguá, Guaratiba, Marapicú, Jacutinga, Aguaçú e Taguaí do distrito de Guaratiba, capitania do Rio de Janeiro, feitos por ordem do vice-rei do Estado do Brasil, conde de Resende [1797]. AHU, Rio de Janeiro, Caixa 165, Doc. 62. Projeto Resgate (Centro de Memória Digital, Universidade de Brasília, http://www.cmd.unb.br/biblioteca.html).

Family Search Digital Collection – www.familysearch.org

Livro de Batismos de Escravos de Jacarepaguá, 1691-1721. Visualized through the websitewww.familysearch.org.

Will and Testament of Bárbara de Marins, 28/04/1728. Livro de Óbitos de Livres e Escravos de Jacarepaguá, 1667-1738. Visualized through the website www.familysearch.org.

Will and Testament of João de Sampaio e Almeida, 07/04/1718. Livro de Óbitos de Livres do Santíssimo Sacramento, 1714-1719. Visualized through the website www.familysearch.org.

Will and Testament of João da Costa, 19/07/1711. Livro de Óbitos de Livres e Escravos de Jacarepaguá, 1667-1738. Visualized through the website www.familysearch.org.

Will and Testament of Miguel de Sampaio e Almeida, 01/02/1714. Livro de Óbitos da Candelária, 1736-1744. Visualized through the website www.familysearch.org.

REFERENCES

Aguiar, Júlia Ribeiro (2012). As Práticas de Reprodução Social das Elites Senhoriais da Freguesia de São Gonçalo: um estudo de caso da família Arias Maldonado (séculos XVII – XVIII). Rio de Janeiro: Monograph. Department of History. Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Almeida, Cândido Mendes de (ed.) (1870). Código Philippino ou Ordenações e leis do reino de Portugal recopiladas por mandado dEl-Rey d. Philippe I [14ª edição]. Rio de Janeiro: Typographia do Instituto Philomathico. [ Links ]

Belchior, Elysio de Oliveira (1965). Conquistadores e Povoadores do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Brasiliana Editora. [ Links ]

Fragoso, João (2001). A formação da economia colonial no Rio de Janeiro e de sua primeira elite senhorial (séculos XVI e XVII). In João Fragoso, Maria Fernanda B. Bicalho and Maria de Fátima S. Gouvêa (eds.), O Antigo Regime nos Trópicos: a dinâmica imperial portuguesa (séculos XVI – XVIII). Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 29 – 71. [ Links ]

Fragoso, João (2003). A nobreza vive em bandos: a economia política das melhores famílias da terra do Rio de Janeiro, século XVII. Algumas notas de pesquisa. Tempo, 15: 11 – 35. [ Links ]

Fragoso, João (2010). Capitão Manuel Pimenta de Sampaio, senhor do engenho do Rio Grande, neto de conquistadores e compadre de João Soares, pardo: notas sobre uma hierarquia social costumeira (Rio de Janeiro, 1700-1760). In Fragoso, João and Gouvêa, Maria de Fátima (eds.). Na Trama das Redes: política e negócios no império português, séculos XVI-XVIII.Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. [ Links ]

Fragoso, João (2012). Introdução. In João Fragoso and Antonio Carlos Jucá de Sampaio (eds.). Monarquia Pluricontinental e a Governança da Terra no Ultramar Atlântico Luso: séculos XVI – XVIII. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad X, 7-16. [ Links ]

Furtado, Júnia Ferreira (2011). Testamentos e Inventários. A morte como testemunho da vida. In Carla Bassanezi Pinksy and Tania Regina de Luca (eds.). O Historiador e suas fontes. São Paulo: Contexto. [ Links ]

Hespanha, António Manuel and Xavier, Ângela Barreto (1998). As Redes Clientelares. In António Manuel Hespanha (coord.). História de Portugal, vol. IV – O Antigo Regime (1620-1807).Lisboa: Editorial Estampa, 339-349. [ Links ]

Krause, Thiago Nascimento (2014). De homens da governança à primeira nobreza: vocabulário social e transformações estamentais na Bahia setecentista. Revista de História (São Paulo), 170: 201-232. [ Links ]

Lavradio, Marquês de (1913) [1779]. Relatório do Marquês de Lavradio, parte II. Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, LXXVI: 289-360. [ Links ]

Lewin, Linda (2003). Surprise Heirs: illegitimacy, patrimonial rights and legal nationalism in Luso-Brazilian inheritance, 1750-1821, Vol. I. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Lopes, Eliane Cristina (1998). O Revelar do Pecado: os filhos ilegítimos na São Paulo do século XVIII.São Paulo: Annablume. [ Links ]

Monteiro, Nuno Gonçalo and Cunha, Mafalda Soares da (2010). Aristocracia, Poder e Família em Portugal, séculos XVI-XVIII. In Mafalda Soares da Cunha and Juan Hernández Franco (eds.). Sociedade, Família e Poder na Península Ibérica. Elementos para uma história comparada / Sociedad, Familia y Poder en la Península Ibérica. Elementos para una Historia Comparada. Lisboa: Edições Colibri/ CIDEHUS – Universidade de Évora / Universidad de Murcia, 47-75. [ Links ]

Monteiro, Nuno Gonçalo (1993). Poder Senhorial, Estatuto Nobiliárquico e Aristocracia. In António Manuel Hespanha (coord.). História de Portugal, vol. IV – O Antigo Regime (1620-1807).Lisboa: Editorial Estampa, 297-338. [ Links ]

Nazzari, Muriel (2001). O Desparecimento do Dote: mulheres, famílias e mudança social em São Paulo, Brasil, 1600-1900. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Pedroza, Manoela (2011). Engenhocas da Moral: redes de parentela, transmissão de terras e direitos de propriedade na freguesia de Campo Grande (Rio de Janeiro, século XIX). Rio de Janeiro: Arquivo Nacional. [ Links ]

Pedroza, Manoela (2012). Sistemas de Transmissão no Município do Rio de Janeiro. In Monarquia Pluricontinental e a Governança da Terra no Ultramar Atlântico Luso: séculos XVI – XVIII.Rio de Janeiro: Mauad X, 165-200. [ Links ]

Rheingantz, Carlos G (1968). Primeiras Famílias do Rio de Janeiro (Séculos XVI-XVII). Vol. II, F-M. Rio de Janeiro: Brasiliana Editora. [ Links ]

Rheingantz, Carlos G (1993). Primeiras Famílias do Rio de Janeiro (Séculos XVI-XVII). Vol. III, Ram-Sim. Rio de Janeiro: Gráfica La Salle. [ Links ]

Schwartz, Stuart B (1988). Segredos Internos: engenhos e escravos na sociedade colonial, 1550-1835. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Silva, Maria Beatriz Nizza da (2005). Ser nobre na colônia. São Paulo: Editora UNESP. [ Links ]

Silva, Maria Beatriz Nizza da (1998). História da Família no Brasil Colonial. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira. [ Links ]

Venâncio, Renato Pinto (1986). Ilegitimidade e Concubinato no Brasil Colonial: Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo. São Paulo: Centro de Estudos de Demografia Histórica da América Latina (CEDHAL-USP) (Estudos CEDHAL, nº 1). [ Links ]

Veríssimo, Antonio Ferreira da Costa (1816). Collecção Systematica das Leis Militares de Portugal, Tomo IV – Leis pertencentes às Ordenanças. Lisboa: Impressão Régia. [ Links ]

Vide, Sebastião Monteiro da (2010). Constituições Primeiras do Arcebispado da Bahia. (introductory study and edition by Bruno Feitler and Evergton Sales Souza) São Paulo: EDUSP. [ Links ]

NOTES

2 The Economy of Favors (economia das mercês) is a concept used to describe modern Portugal by António Manuel Hespanha and Ângela Barreto Xavier based on the Gift Economy (economia do dom) described by Marcel Mauss, linking the moral reciprocities involved in the act of giving and receiving through service practices to the ideals of friendship and loyalty developed in the political and social context of the Ancien Regime in Portugal. Cf. Hespanha & Xavier. 1998. For the application of the Economy of Favors in the case of colonial Rio de Janeiro, cf. Fragoso, João. 2001.

3 The different types of wills and testaments are quite complex and are clearly explained in the studies by Silva, 1998 and Furtado, 2011.