Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

e-Journal of Portuguese History

versão On-line ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH v.9 n.1 Porto 2011

Nobility and Military Orders. Social and Power Relations.(Fourteenth to Sixteenth Centuries)

António Maria Falcão Pestana de Vasconcelos1

1Researcher at CEPESE - Center for Studies on the Population, Economy and Society, Portugal. Post-doctorate scholarship holder from the Foundation for Science and Technology. E-mail: a_pestvasc@hotmail.com

Abstract

This article summarizes the main conclusions of the authors doctoral dissertation. It examines the behavior of the nobility and the Military Orders in their dealings with the established power, and the relationship of this sector of society with these monastic-military institutions, from the late fourteenth century to the first quarter of the sixteenth century. Based on a prosopographic analysis of a broad universe of individuals identified as knights and commanders of the Military Orders, this work also analyses the presence of the nobility in the Military Orders, as well as the growing interest of certain lineages in having their own representatives in these institutions, not only because of the social prestige that this generated, but also because of the economic and patrimonial advantages that might derive therefrom. Throughout this approach to the question, special attention is given to the family relationships established between lineages linked to these institutions, both through the male and the female lines of each family.

Keywords: Portugal; medieval history; nobility; Military Orders; knights; commanders; war

Resumo

Este artigo resume as principais conclusões da tese de doutoramento do autor. Nela é abordado o comportamento da nobreza e das Ordens Militares face ao poder instituído, e o relacionamento deste sector da sociedade com estas instituições monástico militares, desde finais do século XIV até ao primeiro quartel do século XVI. Partindo de uma análise prosopográfica de um universo alargado de indivíduos identificados como cavaleiros e comendadores das Ordens Militares, este trabalho analisa também a presença da nobreza nas Ordens Militares, bem como o interesse crescente de certas linhagens em terem elementos seus, nestas instituições, não só pelo prestígio social, mas também pelas vantagens económicas e patrimoniais que daí podiam advir. Ao longo desta abordagem dá-se uma especial atenção às relações familiares estabelecidas entre linhagens ligadas a estas instituições, quer por parte do elemento masculino, quer por parte do elemento feminino.

Palavras-chave: Portugal; história medieval; nobreza; Ordens Militares; cavaleiros; comendadores; guerra

The aim of this article is to present the main conclusions from my doctoral dissertation entitled Nobreza e Ordens Militares. Relações Sociais e de Poder. (Sécs. XIV a XVI) (Nobility and Military Orders.Social and Power Relations.(Fourteenth to Sixteenth Centuries), defended at the Faculty of Letters of the University of Porto in January 2009.

This work is intended to afford some continuity to other studies already made on the subject of the Military Orders, which served as the starting point for gaining a better understanding of the internal organization, the heritage, the rules of conduct of these institutions, their importance and influence at the political leveltheir relationship with the established powerat the economic levelgovernment and administrationand at the social levelwith extensive lists of individuals who formed the human component of the various orders.2

In my Ph.D. dissertation, in seeking to lay special stress on the study of the human universe of which these institutions were comprised, I undertook a survey of all the individuals mentioned as belonging to the Military Orders. For this purpose, not only did I make use of the specific documentary sources available for each of the militiasthe Orders of the Hospital, Avis, Santiago and Christbut also various works published on this theme, and the other type of sources, particularly the writings of the chroniclers,3 and the peerage and genealogical books.4 This made it possible for me to compile a prosopographic record of 427 individuals, identified as knights and commanders of the Military Orders present in Portugal during the period from the rise to power of the dynasty of Avis to the end of the reign of Dom Manuel.

Next, I identified the genealogy of this human universe, which led me to select and study 33 lineages5those that, because of the number of their members present in these institutions, gave me greater guarantees of being able to obtain an overall picture of the important role that the monastic-military institutions played in the strategy devised by these lineages. It should also be noted that all the lineages selected belonged to the nobility.

This study is divided into two parts, each composed of two chapters: the first deals with the theme of the military orders, while the second provides an analysis of the nobility.

The dissertation begins with a synthesis of the evolution of the various Military Orders (Avis, Christ, Santiago and Hospital) from the reign of Dom Dinis to the reign of Dom Manuel, focusing in particular on the relationship between these institutions and the established power.

The reign of Dom Dinis is therefore the starting point for our approach to this question, since it was during this period that the Military Orders underwent the first changes that were to leave their mark on the following centuries. If, until that time, the Military Orders had generally been seen as institutions of an essentially religious/military nature, from the late thirteenth/early fourteenth century onwards, because of the lands donated to them, they began to be seen as great territorial powers, endowed with extensive estates that it was in their interest to control and render profitable.

As far as the Order of Avis is concerned, Dom Dinis intervention in the daily life of this militia took place at different moments and at various levels:

- The appointment of the Master of the Orderthe first appointment was made in 1311, with the nomination of Dom Garcia Peres do Casal,6 the second in 1316, with the election of Dom Gil Martins;7 and the last with the nomination of Dom Vasco Afonso as the replacement for the same Dom Gil Martins, whom the king appointed as the master of the newly created militia of Our Lord Jesus Christ;

- The pursuit of a policy which, in the short term, freed the Order of Avis from its links to the Order of Calatrava, thus avoiding the need for the representatives of the Castilian militia to confirm the master appointed in Portugal.8

Dom Dinis also gave special attention to the Order of Santiago, intervening in matters relating to the estate of this militia and creating the necessary conditions for the restructuring of its administration. In parallel to this, he implemented a policy of awarding privileges through charters of donation, trading rights and patronages, which enabled him to endow this militia with a larger and more concentrated estate, while at the same time successfully marking out the area of its implantation and influence.9

Another of Dom Dinis concerns was to place the Order of Santiago amongst the group of the Crowns interests within the framework of international policyseparating the Order in Portugal from its headquarters at Uclés, and consequently from its subordination to the master or general of that Order based in Castile10thus succeeding in bringing an end to the rather equivocal situation that had existed until then regarding the obedience and loyalty of the holders of countless lands and castles on the border between the two countries in the event of any conflict between them.

Besides his interference in the affairs of the Orders of Avis and Santiago, Dom Dinis also made his presence felt, more forcefully, in the process leading to the extinction of the Order of the Temple and the consequent creation of Order of Our Lord Jesus Christ.11 The Crowns intervention in this institution was not only limited to this foundational act, but it was also to be noted in the appointment of its masters, beginning with the appointment of Dom Gil Martins, until that time the Master of the Order of Avis, and later, on his death, with the appointment of Dom João Lourenço, contrary to the rules that provided for the free election of the master by the community.

Dom Dinis also intervened in the internal life of the Order of the Hospital, seeking to check some of the seigniorial impulses of some of its knights.12 He interfered in matters of a legal and/or administrative nature,13encouraging the signing of various trade and exchange agreements, always with the aim of establishing his influence and power over the reorganization of his realm.14

As far as international policy was concerned, the suppression of the Order of the Temple led Dom Dinis to hand the property of the Knights Templar to the newly created militia of Our Lord Jesus Christ,15 thus preventing this estate from being annexed by an international Orderthe Order of St. John of Jerusalem.

The reigns of Dom Afonso IV, Dom Pedro I and Dom Fernando were characterized by a continuity in the Crowns relationship with these institutions, even though there were clearly certain differences in the way these kings attempted to influence the life of these organizations.

Afonso IVs relationship with the Order of Avis was marked by his constant attempts to control the abuses perpetrated by the members of this militia in their dealings with other powers, particularly the concelhos,16whereas, in the case of Dom Pedro I, his relationship with this institution was marked by the granting of certain letters of privilege, both to the institution and its members, but above all by the appointment of his son Dom João as its master.17 In his turn, Dom Fernando, his actions dictated by the international conjuncturewars with Castileand the behavior of the queen Dona Leonor, who sought to control the master of this militia, actually ended up imprisoning the latter in Évora castle.18

In the case of the Order of Santiago, we should note the importance that both Dom Afonso IV and Dom Fernando attached to the process of succession that was followed in appointing the master of this militia. The former clearly demonstrated the great care and attention that he dedicated to this process when, after the death of Dom Pedro Escacho, he requested information about the way that the election of the new master should take place;19 the latterDom Fernandohidebound by the crisis that marked his reign, chose to entrust the mastership of this militia to someone who merited his complete confidenceDom Fernão Afonso de Albuquerque. As far as Dom Pedro I is concerned, his behavior towards this militia, just like all the others, was marked by the granting of privileges both to this Order and to its members. At the same time, the absence of any conflict between these two institutions makes it possible for us to consider that his behavior towards this Military Order was altogether quite pacific.20

Throughout this period, the Crowns position in relation to the Order of Christ was marked, at certain moments, by some divergences between the various monarchs and masters, episodes that always culminated in the resignation of the latter. This was what happened when Dom Afonso IV ascended the throne, with the consequent resignation of Dom João Lourenço, and later, when Dom Pedro I ascended the throne and the master of the Order at that time, Dom Rodrigo Eanes, resigned his position. Such situations clearly highlight the power and influence that the Crown had over this institution, immediately dismissing those who did not give it their support and placing people that it could trust in charge of the Order.

In view of what has just been said, it is therefore not surprising to find that, throughout the period in question, all the monarchs paid special attention to the process of succession in regard to the mastership of this militia. This is clearly proved by Dom Afonso IVs appointments of Dom Martim Gonçalves Leitão, his brother Estêvão Gonçalves Leitão and Rodrigo Eanes; by Dom Pedro Is appointment of Dom Nuno Rodrigues Freire de Andrade; and Dom Fernandos appointment of Dom Lopo Dias de Sousa, the queens nephew.21

The Crowns placing of trusted people in charge of this Military Order was a guarantee that they could depend on this institution whenever they needed to. This seems to have been the case with the presence of this Military Order fighting on the side of Dom Afonso IV at the Battle of Salado; the presence of this militia in the aid that Dom Pedro I decided to offer Castile in the war against Aragon; in the support that the Order gave Dom Fernando throughout the successive campaigns against Castile; and, given the Great Schism in the Catholic Church, in the choice to render obedience to Avignon or Rome depending on the position of the monarch.

As far as the Order of the Hospital is concernedsince this was an international order whose leadership was located outside Portugalthe Crowns dealings with this institution amounted more to a demonstration of the exercise of power and the requirement that the Order fulfill its duties. It is in this context that we should understand Dom Afonso IVs actions in raising obstacles to the free circulation both of goods and people from the Order, as well as obliging it to provide evidence of the jurisdictional rights that it claimed to be entitled to.22 For Dom Pedro I, the exercise of his power and authority was to be displayed in another way, namely through the exercise of his royal prerogativegranting privileges both to the Order and its members.

The policy followed by Dom Fernando differed from that of his predecessors. As a result of the schism existing in the Christian world, the king did not shrink from calling into question the nomination made by the Grand Master of the Order of the Hospital of Dom Álvaro Gonçalves Camelo for the position of Prior of Crato. By momentarily choosing to pay obedience to Pope Clement VII, Dom Fernando managed to achieve his wishes, namely the appointment of Pedro Álvares Pereira to the position of Prior of the Portuguese Knights Hospitaller. Once again, this clearly demonstrated the Crowns concern with placing trustworthy people at the head of these institutions.23 It was not by chance that the king sought the opinion of the Prior of Crato about matters of government and later appointed him governor of the city of Lisbon.

Throughout the period corresponding to the reigns of Dom João I, Dom Duarte and Dom Afonso V, the most notable feature of the relationship between the Crown and the Military Orders was the Crowns concern with exercising control over these institutions.

This is how we can understand that the successive kings, or those who momentarily exercised power on their behalf, always paid particular attention to the nomination and appointment of the governors of the Orders of Avis, Santiago and Christ, and to the appointment of the Prior of Crato, in the case of the Order of the Hospital. At first, these positions were occupied by people who did not belong to the Royal FamilyDom Fernão Rodrigues de Sequeira in the Order of Avis; Dom Fernando Afonso de Albuquerque, and after his death Mem Rodrigues de Vasconcelos, in the Order of Santiago; Dom Lopo Dias de Sousa in the Order of Christ; and Dom Álvaro Gonçalves Camelo24, and on his death Dom Nuno Gonçalves de Góis, as the Prior of the Order of the Hospital. In the short term, however, this practice became unthinkable, in view of the increasingly centralized policy adopted by these sovereigns.

Thereafter, the government and administration of the Military Orders was handed as a matter of course to the Infantes, members of the Royal Family, and preferably the sons of kings. When this did not happenas in the case of the Order of the Hospitalsuch appointments always took into account the proximity of the appointee to the monarch, and there were even ties of kinship between the two, as in the case of Dom Vasco de Ataíde, one of the godfathers of the future Dom João II.

Not only did the Crown strictly adhere to this policy of carefully choosing certain specific people to take charge of the governorship and administration of these militias, but it also sought to intervene in these institutions in order to clearly exert its authority and power. It is therefore not surprising to find that the successive monarchs marked their presence in these institutions through a policy of granting jurisdictional, fiscal, economic or judicial privileges to the Orders and their members, as well as letters of pardon and exemptions, while also providing them with services, donations, pensions, authorizations and appointments.

In the reigns of Dom João II and Dom Manuel, the relationship between the Crown and the Military Orders cannot be understood without taking into account the fact that, before ascending the throne, both monarchs were already Masters of Military OrdersDom João, as the Infante and heir to the throne was already responsible for the administration of the Orders of Avis and Santiago, and Dom Manuel, simultaneously Duke of Viseu and Duke of Beja, was already the Governor of the Order of Christ. Another factor to be borne in mind is that they were both fully aware of the importance that these militias had within the fabric of society, and the support and loyalty that they could provide. This situation certainly contributed to the fact that, after being acclaimed king, they both refused to give up their governorships of their respective Orders.

It is therefore not surprising to find that, in combining their prerogatives as sovereigns with those that they enjoyed as governors of the aforementioned militias, both Dom João II and Dom Manuel paid particular attention to the rules governing each of those institutions. In this context, they both ordered the formation ofCapítulos Gerais (General Chapters)the Order of Avis in 1488, whose decisions were applied in Santiago in 1490; and the Order of Christ in 1503with the aim of ensuring the approval of new rules to better preparetheir militias for meeting the new challenges facing the Crown and consequently the Orders.25

Besides this stance that each of the monarchs took towards the Order for which they were responsible, we should also mention the fundamental points in the relationship that each of the sovereigns was to maintain with the other Military Orders.

Thus, as far as the reign of Dom João II and his relationship with the Order of Christ are concerned, attention is drawn to the death of the then governor of the Order, Dom Diogo, at the hands of the monarch and the subsequent appointment of his brother Dom Manuel as the governor of this same militia. In keeping with what had always been the Crowns policy towards these institutions, the stance taken by Dom Manuel/the Orderfollowing the death of his brother/the Governormade a decisive contribution to the Crowns granting a series of benefits, donations and privileges.26

For the Order of the Hospital, the Crowns position was not substantially different from the one that it adopted towards the other institutions. Thus, in accordance with its policy of limiting the seigniorial power of the Order, the king was to intervene in this institution by reducing certain privileges, or by marking out strict limits for its area of influence. Such a situation did not invalidate the granting of privileges and donations both to the Order as an Institution and to its members. On the death of the Prior of Crato, Dom Vasco de Ataíde, the kings godfather, the Crown would again intervene in the internal affairs of this militia, namely in the appointment of his successor. The choice fell upon Dom Diogo Fernandes de Almeida, the son of the first Count of Abrantes, originating from a family that had always demonstrated great proximity and loyalty to this king.27

Besides these moments referred to above, mention should also be made of the fact that the governorships of the Orders of Avis and Santiago were handed to the prince and heir to the throne Dom Afonso, and later, on his death, to Dom Jorge de Lencastre, the bastard son of Dom João II.

When Dom Manuel ascended the throne, the relationship with the other Military Orders was immediately and forcibly imposed with the handing of the governorship of the Orders of Avis and Santiago to Dom Jorge. The references to the king in the various rulings made by Dom Jorge, and his presence on the estates belonging to the Order of Santiago, are a clear example of the kings determination to impose the Crowns control over these institutions.28 This situation would only be attenuated to some extent when the king implemented some of the clauses from the will of Dom João II relating to this son of his, instituting a house for him and also preparing his marriage.

In the case of the Order of the Hospital, Dom Manuel was also to place this institution within his sphere of influence by granting and confirming a wide variety of privileges. The Crowns presence was also felt, as usual, when it came to deciding upon the succession of the Prior of Crato, Dom Diogo Fernandes de Almeida, who had died in the meantime. Dom Manuel was therefore to request the Pope to nominate as the prior of the Portuguese Hospitallers Dom João de Meneses, the count of Tarouca, who until then had been the commander of Sesimbra, of the Order of Santiago.29

In relation to the Order of Christ, Dom Manuels actions were closely bound up with the fact that he was simultaneously master and king. This is how we can best explain the profound changes that were made to this militia, namely through the creation of the pensions of ten thousand reais, the new benefices of twenty thousand reais, and the 50 benefices of the Royal Patronage, resulting from the annexation of the same number of churches from the Royal Patronage.30

In studying the theme of the Military Orders, I have sought to point out the main differences in the rules governing these institutionsstressing the rules of conduct that were to be obeyed by all those wishing to enter these institutions as friar-knights. I have also sought to stress the reforms that over time were to lighten the modus vivendi of these knights, both at a temporal and a spiritual level. This process was designed to make them better prepared for the Crowns great aim of expansion into North Africa and the Orient, while, at the same time, making the orders more attractive to the sector of society that it was most important to captivate; namely the nobility.

In fact, the changes to the rules, which made it possible for friar-knights to be property owners and to bequeath their possessions by will,31 as well as the possibility of their marrying,32 allied to the fact that these institutions could offer those entering the order honor (war), power (through the holding of positions of high rank) and benefits (through the administration of benefices and monetary allowances), certainly helped to ensure that the interest of the nobility in joining the orders remained high over successive reigns, in other words from the time of Dom João I to that of Dom Manuel.

The second part of this dissertation deals in particular with the subject of the nobility. I therefore begin by analyzing the behavior of this sector of society towards the monarchy, from the reign of Dom João I to that of Dom Manuel, giving special emphasis to the strategies adopted by noblemen.

Following on from what was said above, it is important to stress the idea that, throughout the period under consideration (from Dom João I to Dom Manuel), the nobility always displayed a great capacity for adapting to the political, economic and social conjuncture of each moment.

Many of the positions adopted by the nobility were therefore the fruit either of interests existing among the different sectors of this class or of the increasing rivalry between different lineages seeking to gain ever greater influence and status, or of the constant search for prominence on the part of certain branches in relation to others, even within the same lineage. However, the prominence and influence of the nobility in medieval society had always called for the adoption of a strategy, be it one of support, rejection or even submissiveness at certain moments in the life of the nation, always trusting that the choice that was made would result in their ending up on the winning side. So, it is therefore not surprising to find that, throughout the period under analysis, and particularly at the most troubled times in the nations history (the election of the Master of Avis, and the Battle of Aljubarrota;33 the regency of the Infante Dom Pedro, and the Battle of Alfarrobeira;34 participation in the conspiracies against Dom João II;35 support for the succession of Dom Manuel in detriment to Dom Jorge),36 the nobility, as a whole, never adopted a uniform strategy and behavior towards the different factions in confrontation with one another. In fact, the adoption of a certain strategy on the part of one particular branch, lineage or sector of the nobility, resulting in the victory of a certain faction, was in itself only an added advantage for the nobles with a view to their seeing their efforts rewarded, either through the granting of benefices, property or even noble titles, by the power that came to be instituted.

The nobilitys constant search for ever more and better benefits soon led them to devise strategies for situating themselves close to the court and the monarch, frequently with the aim of joining the restricted circle of royal counselors, gaining influence in the administration and government of the realm, and occupying the main positions in the more important institutions, such as the monastic and military Orders.

The support given by the nobles to the policy for expansion into North Africa, which had begun in the reign of Dom João I with the conquest of Ceuta in 1415, and was successively encouraged by the monarchs who followed him, not only provided the various sectors of the nobility with the ideal conditions for exercising their main functionwarbut also enabled some sectors, namely those situated in the middle nobility of the court and the middle and low regional nobility, to take up arms and see their deeds rewarded with noble titles and the appointment to important positionsas governors and captains of fortresses in Moroccoas well as seeing their personal prestige and that of their lineage increased, at the same time providing them with a new source of income and an increase in their wealth and property.37

It is also in this context that we can understand the strategy adopted by the nobility in its support for Dom Afonso Vs claim to the crown of Castile, actively participating in the different episodes of war occurring in the neighboring country, most notably the Battle of Toro.38

However, it was when Dom João II ascended the throne and implemented his centralizing policy that the high nobility suffered its greatest setbacksand here I am referring in concrete terms to the suppression of the House of Bragança and the death of its duke,39 and the death of Dom Diogo, duke of Viseu. However, this centralizing policy, which greatly reduced the privileges enjoyed by the grandees of the realm, did not prevent the monarch from creating the necessary conditions for other sectors of the nobility to prosper. I am referring in concrete terms to the attention that the monarch began to pay to all maritime and trading activity along the coast of West Africa, in which many members of the regional middle and low nobility became involved.40It was precisely as a result of this participation that commercial activity and profit seeking began to be regarded by certain sectors of the nobility as another way of life, in contrast to their traditional view of enrichment through the granting of benefits, the conquest of honor and the recognition of armed services. In this context, the arrival of Vasco de Gama in India and the consequent opening of a new trade route with direct access to spices represented a clear turning point in the strategy adopted by some sectors of the nobility in terms of their involvement in commercial activity.

The ascension to the throne of Dom Manuel, the restoration of the House of Bragança, and the creation of the House of Coimbra, were events that led to the reorganization and the definition of the hierarchy of the nobility. Changes that made it possible for the different sectors, depending on the hierarchical level to which they belonged, to devise strategies that were more favorable for their own interests, enabling them to choose their preferred area of interventionNorth Africa and/or the Orientand the nature of their particular interventionwar and/or trade.

Even though, for most of the titled nobility who already had their own jurisdictional dominions and higher offices in the royal household, the services that they rendered at the Court continued to be seen as more honorable and demonstrative of their power and social distinction,41 this did not prevent them from choosing North Africa as their preferred area of intervention, and from seeing armed service as the best way of increasing their prestige, honor and wealth. Illustrative of this fact was the participation of the Duke of Bragança in the conquest of Azamor42 and of the other members of the titled nobility who remained there continuously as captains and governors of the different Moroccan fortresses,43 besides the large number of untitled noblemen, particularly the second sons and representatives of families of lesser importance. Contrary to what happened in the case of North Africa, there were few individuals from distinguished noble families who travelled to the Orient, there being no reference to any member of the titled nobility there,44although this situation did not, however, prevent the award of the main overseas posts to members of the nobility. In fact, command of the voyages of exploration and navigation, as well as the positions as officers of the House of India were preferably handed to knights and squires, with the captaincies of the ships sailing to India and the fortresses being reserved for the members of the high nobility, as well as the governorship of the State of India.45 In fact, in the case of this latter position, those who were chosen were also sometimes close relatives of important members of the high court nobility.

Following this study of the behavior of the nobility in the period between the rise to power of the Dynasty of Avis and the end of the reign of Dom Manuel, I shall now analyze the presence of this sector of society in the various Military Orders.

The genealogical reconstruction of the 33 noble families already referred to makes it possible not only to characterize them inside the social grouping to which they belonged (note that of the families in question, referred to 84% belonged to the group of the Court Nobility, and 16% to the group of the Regional Nobility, representing as a whole the main lineages of the Portuguese nobility of that time), but also to note the ever greater interest that these families showed in having representatives in these institutions. Having members of ones family in the Military Orders was not only a matter of social prestige, but also brought economic and hereditary advantages.

If, until the beginning of the fourteenth century, the equal sharing of a familys estate was the common practiceleading to its division among all the members of the family and consequently resulting in a greater fragmentation of the inheritancethe appearance of the morgadio system of entailment, with the consequent indivisibility of the estate and its transmission solely to the first-born son, led many of the second sons of the main noble families to opt for a career of armed service in one of the Military Orders, as a way of guaranteeing that they could maintain their status within the class to which they belonged.

It is therefore not surprising that, from the mid-fourteenth century onwards and throughout the fifteenth century, there was an ever greater number of aristocrats to be found joining the Military Orders.46

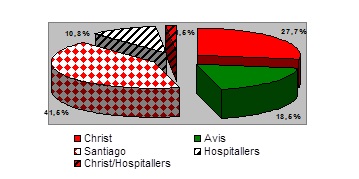

Thus, for the period between 1385 and 1450, we can note the presence of an already significant number of nobles in the various Military Orders, with 41% of them opting for the Order of Santiago, followed by roughly 28% joining the Order of Christ, 19% in the Order of Avis, and, finally, 11% in the Order of the Hospital.

Graph 1Distribution of the human component in the different Military Orders1385/1450

Various factors contributed to the preference shown by the nobility for the Order of Santiago, most notably:

- the legacy and family tradition that some lineages had in this militia;

- the fact that this institution accepted the possibility of married friars whose descendants could also join the order;

- the opportunity that this militia offered those entering the order to own and control the orders propertybeneficesto their own advantage,

- the possibility of being able to transmit this property to their descendants, relatives and children, also allowing for their families to live in geographical regions which, since the reconquest, had been closed to the nobility, such as the central and southern regions of Portugal, which were the privileged areas for the implantation of the Military Orders;

- the great political and economic influence that the Order of Santiago enjoyed, both internally and externally;

- the fact that its masterMem Rodrigues de Vasconceloswas a member of the high nobility, who enjoyed the kings trust and confidence, as can be understood from Dom João Is active participation in his election, and the fact that the person chosen to succeed him after his death was, for the first time, a member of the Royal Householdthe Infante Dom João.

It is in this context that we can understand the preference shown for this militia by a considerable number of noble families, during the period under study here.47

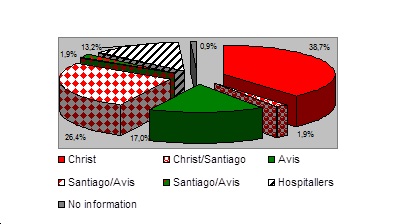

This interest displayed by the nobility in the Military Orders was to increase considerably in the period between 1450 and 1495, with a remarkable growth of 63% in the number of noble members compared with the previous period. Also to be noted is the fact that these men chose to enter another institution to the one that had previously been preferred by most of them. Thus, for the period under study, the order chosen by most nobles was that of the Order of Christ, with roughly 39% of all choices, followed by the Order of Santiago (26%), the Order of Avis (17%), and finally the Order of the Hospital (13%).

Graph 2Distribution of the human component in the different Military Orders1450/1495

As far as the Order of Santiago is concerned, it can be seen that there was an almost complete stagnation in the number of members of the nobility joining the institutiononly one more member than in the previous period. So it can be said that, of the families mentioned in the previous period, almost all maintained their preference for the Order of Santiago.48

In the case of the Order of Christ, the high percentage of new members was due to a series of factors, most notably:

- the attempt made to identify the Order of Christ with what was to become the great project of the Dynasty of Avisoverseas expansionismwhich began with the conquest of Ceuta in 1415 in which the master of that same order, Dom Lopo Dias de Sousa took part.49

- the possibility of the nobility benefiting from this institution to become associated with the Crowns project and attaining their own objectives of honor and wealth.

- the appointment of Prince Henry the Navigator as Governor and Administrator of this militia (1420), strengthened by his efforts to prepare it for fighting the Infidel, and for the challenges of this dynastys expansionist policy50North Africa and the West Coast of Africa;

- the presence of its administrator and governor in command of the expedition to conquer Tangier, with the participation of some of the commanders of this militia;51

- the presence of its administrator and governor in command of the expedition to conquer Alcácer Ceguer, in 1458.52

- the concern with maintaining the administration and government of the militia within the Royal Familyinitially entrusted to the Infante Dom Fernando,53 and, after his death, to the Infante Dom Diogo,54and later to his brother Dom Manuel.55

Taking into account the fact that one of the main objectives of the nobility was to gain access to new sources of income, increase their prestige and honor, it is not surprising that, throughout this period, those who entered the Order of Christ did so with the aim of finding new sources of wealth by owning and administering certain properties, namely feudal benefices. It should be stressed that these estates were located in areas where, until then, the nobility had not traditionally owned property, or, in other words, the whole of the region to the south of the River Douro and the valley of the River Tagus. In fact, it was precisely during the reign of Dom Afonso V that the first noble titles were granted that brought their holders possession of estates in this geographical area.56

In this way, we can understand that many of the second sons of the main lineages of the kingdom, who had entered the Military Orders, also came to enjoy ownership and power over the estates of the Order of Christ which were mainly located in that region.57

This reality, while demonstrating a growing feudalization on the part of the nobility over a territory that until then had been closed to them, did, however, amount more to a possession that was consented and controlled by the Crown rather than being one that was effectively controlled by the noble families themselves. It should be remembered that the administration and government of the Order of Christ was in the hands of the members of the Royal Household, subject to the will of its governor, who benefited those who merited his trust and confidence, but also the members of the militia belonging to noble families that it was in the Crowns interest to benefit as part of its global strategy.

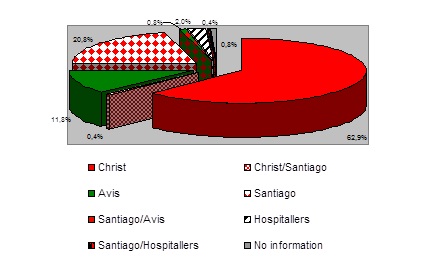

For the period between 1495 and 1521, the number of members of the nobility present in the Orders increased by 131% in relation to the previous period.

Thus, in the case of the lineages covered by this study, it should be noted that their main preference was for the Order of Christ, which accounted for roughly 63% of choices, followed by the Order of Santiago with roughly 21%, the Order of Avis with roughly 12%, and finally the Order of the Hospital with only 2% of all choices.

Graph 3Distribution of the human component in the different Military Orders1495/1521

By not renouncing the government and administration of the Order of Christ and implementing the necessary internal reforms, Dom Manuel created the essential conditions for his being able to enjoy the full benefits of an estate and an income that had previously been closed to him, as the land and property had previously been the hereditary estate of the Church. After his reforms, he was able to use it for the benefit of whoever he wished to grant privileges to.58

Thereafter the great projects of the monarchy also became the aims of the Order of Christ, so that entry into that institution brought added advantages to its new members.

From 1495 until the end of Dom Manuels reign, most of the noble families under study here chose to follow a strategy of channeling the greatest number of its individual members into the Order of Christ, so that this soon began to represent, if not all of the nobilitys preferences, at least its great majority.59

There were other lineages that sought to maintain their preferential links with what until then had been theOrder of the Family, but given the nature of the conjuncture at that time, the important thing was for them to place their members in the Order of Christ.60

This growth in the Order of Christ highlights the importance and influence that this militia was beginning to gain in the kingdom, reaching its peak when it began to be governed and administered by the king himself.

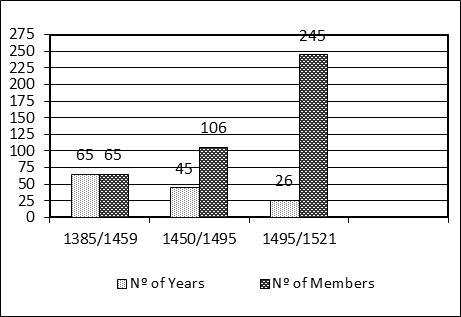

Thus, during the period ranging from the ascension to the throne of Dom João I to the end of the reign of Dom Manuel, it can be seen that the number of individuals entering the Military Orders kept growing, reaching its peak in the reign of Dom Manuel.

Graph 4Relationship between the number of years and the number of people entering the Military Orders

The growth in the number of individuals from the nobility to be found serving as members of the Military Orders provided the Crown, especially during the reign of Dom Manuel, with the possibility of controlling large sections of the nobility and ensuring their dependence upon its favors, by awarding privileges and granting the estates of these institutions, while simultaneously placing them at the service of the Crown.

Bibliography

Abranches, Joaquim dos Santos (1895). Fontes do Direito Ecclesiastico Portuguez. I Suma do Bullario Portuguez, Coimbra: Tip. do Seminário. [ Links ]

Almeida, Fortunato de (1967-1971). História da Igreja em Portugal, 4 vols., 2º edição, preparada e dirigida por Damião Peres. Porto: Portucalense Editora. [ Links ]

Álvaro Lopes de Chaves, Livro de apontamentos, 1438-1439(1984). Intr. e transcrição de Anastácia Mestrinho Salgado e Abílio José Salgado. Lisboa: INCM. [ Links ]

Archivo Histórico Portuguez(1903-1916). Dir. de Anselmo Braancamp Freire, 11 vols., Lisboa: [s.a.]. [ Links ]

Arnaut, Salvador Dias (1986). D. Fernando: o homem e o governante. In Anais da Academia Portuguesa da História. Lisboa: [s.l.], 11-33. [ Links ]

As gavetas da Torre do Tombo(1960-1977). Ed. A. da Silva Rego. Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos, 12 vols. [ Links ]

Ayala Martinez, C. and Villalba Ruiz, F. J. (1989). Precedentes lejanos de la crise de 1383: circunstancias politicas que acompañan al Tratado de Santarém. In Actas das II Jornadas Luso-Espanholas de História Medieval. Porto: Centro História da Univarsidade do Porto / INIC, vol. I: 233-245. [ Links ]

Documentos das chancelarias reais anteriores a 1531 relativos a Marrocos(1915-1934). Edição de Pedro de Azevedo, 2. vols., Lisboa: Academia das Ciências de Lisboa. [ Links ]

Barros, João de (1988). Décadas da Ásia de João de Barros: dos feitos que os portugueses fizeram no descobrimento e conquista dos mares e terras do Oriente. [Lisboa]: Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda. [ Links ]

Brandão, Fr. António (1973-1980). Monarquia Lusitana. Parte III, IV, V e VI, Lisboa: INCM. [ Links ]

Brito, Fr. Bernardo de (1973-1975). Monarquia Lusitana. Parte I e II. Lisboa: INCM. [ Links ]

Bullarium Militiae Calatravae(1761). Madrid. [ Links ]

Castanheda, Fernão Lopes de (1979). História do Descobrimento e Conquista da Índia pelos Portugueses. Intr. e revisão de M. Lopes de Almeida. Tesouros da Literatura e da História. 2 vols. Porto: Lello & IrmãoEditores. [ Links ]

Castelo-Branco, Manuel da Silva (1974). Uma genealogia medieval. In Estudos de Castelo Branco, vol. 48-49. [ Links ]

Chancelarias Portuguesas. D. Duarte[1999]. Org. e rev. João José Alves Dias. Lisboa: Universidade Nova. Centro de Estudos Históricos. [ Links ]

Chancelarias Portuguesas. D. Pedro I (1357-1367)(1984). Edição de A.H. de Oliveira Marques. Lisboa: INIC. [ Links ]

Coelho, Maria Helena da Cruz (2005). D. João I, o que re-colheu Boa Memória, Lisboa: Circulo de Leitores. [ Links ]

Corpo Diplomático Português contendo todos os tratados de paz, de aliança, de neutralidade ...(1846). Compil. por Visconde de Santarém. Paris: J.P. Aillaud. [ Links ]

Correia, Gaspar (1975). Lendas da Índia. (Introdução e Revisão de M. Lopes de Almeida) in Tesouros da Literatura e da História. Porto: Lello & Irmão Editores, , 4 vols. [ Links ]

Corte-Real, Gilda da Luz de França Passos Vieira (2004). A batalha de Alfarrobeira: nobreza e relações de poder, Porto: Edição policopiada (Dissertação de mestrado em História Medieval e do Renascimento, apresentada à Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto). [ Links ]

Costa, João Paulo de Oliveira e (2000). A Nobreza e a Expansãoparticularidades de um fenómeno complexo. In A Nobreza e a ExpansãoEstudos Biográficos, Cascais : Patrimónia. [ Links ]

Costa, João Paulo de Oliveira e(2005). D. Manuel I, 1469-1521, Um Príncipe do Renascimento. Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores. [ Links ]

Costa, Paula Maria de Carvalho Pinto (1999/2000). A Ordem Militar do Hospital em Portugal: dos finais da Idade Média à Modernidade. In Militarium Ordinum Analecta, nº 3/4, Porto: Fundação Engº António de Almeida. [ Links ]

Costa, Paula Maria de Carvalho Pinto (2001). D. Dinis a Ordem do Hospital: dois poderes em confronto. InActas da II Semana de Estúdios Alfonsíes. Puerto de Santa Maria. [ Links ]

Costa, Paula Maria de Carvalho Pinto; Vasconcelos, António Pestana de (1997). Christ, Santiago and Avis: an approach to the rules of the Portuguese military orders in the Middle Ages. In The Military Orders: Welfare and Warfare. Ed. Helen Nicholson. Aldershot: Ashgate, vol. 2, pp. 251-257. [ Links ]

Crónica dos sete primeiros reis de Portugal(1952-1953) 3 vols., Lisboa: Academia Portuguesa da História. [ Links ]

Cunha, Mafalda Soares da (2004). A Casa de Bragança e a Expansão, séculos XV-XVII. In Actas do Colóquio Internacional A Alta Nobreza e a Fundação do Estado da Índia. Lisboa: C. H. de Além Mar/ U.N.L./I.I.C.T./C.E.H.C.A.: 303-319. [ Links ]

Cunha, Mafalda Soares da (1996). A nobreza portuguesa no início do século XV: Renovação e continuidade. In Revista Portuguesa de História, tomo XXXI, Coimbra: FLUC e Instituto de História Económica e Social: 119-252. [ Links ]

Cunha, Mafalda Soares da (1990). Linhagem Parentesco e Poder. (A casa de Bragança 1384-1483), Lisboa: Fundação da Casa de Bragança. [ Links ]

Cunha, Mafalda Soares da (1988). D. João II e a construção do Estado Moderno. Mitos e perspectivas historiográficas. In Arqueologia do Estado (Actas das primeiras jornadas sobre formas e organização e exercício dos poderes na Europa do Sul, Séculos XIII-XVIII), Lisboa: História & Crítica, p. 652. [ Links ]

Cunha, Maria Cristina Almeida e (1989). A Ordem Militar de Avis (das Origens a 1329). Porto: Edição poli copiada (Dissertação de mestrado apresentada à Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto). [ Links ]

Cunha, Maria Cristina Almeida e (1995). A monarquia Portuguesa e a Ordem de Avis até ao final do reinado de D. Dinis. In Revista da Faculdade de LetrasHistória. 2ª série, vol. XII, Porto. [ Links ]

Cunha, Mário Raúl de Sousa (1991). A Ordem Militar de Santiago (das origens a 1327). Porto: Edição Poli copiada (Dissertação de mestrado apresentada à Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto). [ Links ]

De Witte, Charles Martial (1956). Les Bulles Pontificales et lExpansion Portugaise au XV ème siècle. InRevue dHistoire Ecclésiastiquem, Louvain, vol. LI, pp. 5-46 [ Links ]

Descobrimentos Portugueses. Documentos para a sua história(1988).(Publicados e prefaciados por João Martins da Silva Marques), vol. 1 e supl., vol. 2, tomo I e II, vol. 3, Lisboa, I.N.I.C. [ Links ]

Dias, Pedro (1979). Visitações da Ordem de Cristo de 1507 a 1510 (Aspectos Artísticos), Coimbra: Instituto de História de Arte, FLUC. [ Links ]

Dinis, A. J. Dias (1960). Estudos henriquinos. Coimbra: Atlântida. [ Links ]

Direitos, Bens e Propriedades da Ordem e Mestrado de Avis, Benavila e Benavente e seus termos [1556](1950). Ed. de José Mendes da Cunha Saraiva, sep. de Ocidente, Lisboa: 52-55. [ Links ]

Duarte, Luís Miguel (2005). D. Duarte. Requiem por um Rei triste, Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores. [ Links ]

Fernandes, Fátima Regina (1996), O Reinado de D. Fernando no âmbito das relações Régio-Nobiliárquicas. Porto: Edição poli copiada (Dissertação de Doutoramento em História apresentada à Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto). [ Links ]

Ferreira, Maria Isabel Rodrigues (2004). A Normativa das Ordens Militares Portuguesas (Séculos XII-XVI). Poderes, Sociedade e Espiritualidade. Porto: Edição poli copiada (Dissertação de Doutoramento em História apresentada à Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto) [ Links ]

Ferro, Maria José (1983). A nobreza no reinado de D. Fernando e a sua actuação em 1383-1385. In Revista de História Económica e Social, nº 12, 45-89. [ Links ]

Figueiredo, José Anastácio (1800). Nova história da militar Ordem de Malta e dos senhores grão-priores della em Portugal. Lisboa: Officina de Simão Thadeo Ferreira, 3 vols. [ Links ]

Fonseca, Luís Adão da (2005). D. João II, Rei de Portugal. Lisboa: Circulo de Leitores. [ Links ]

Freire, Anselmo Bramcamp (1996). Brasões da Sala de Sintra, 3 vols., Lisboa: INCM. [ Links ]

Gayo, Felgueiras (1938-1941). Nobiliário de Famílias de Portugal. Edição de Agostinho de Azevedo Meirelles e Domingos de Araújo Affonso, 28 tomos, Braga: Efficinas Gráficas PAX. [ Links ]

Godinho, Vitorino Magalhães (1962). A Economia dos descobrimentos Henriquinos. Lisboa: Sá da Costa. [ Links ]

Góis, Damião (1926). Chronica do Serinissimo Senhor Rei D. Manoel. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade. [ Links ]

Góis, Damião de (1790). Chrónica do Sereníssimo Príncipe D. João, Coimbra: Oficina da Universidade. [ Links ]

Gomes, Saúl António (2005). D. Afonso V, o Africano. Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores. [ Links ]

Guimarães, José Vieira da Silva (1916). Marrocos e os três mestres da Ordem de Cristo. Comemorações do V Centenário da tomada de Ceuta. Coimbra: Imprensa Universitária. [ Links ]

Krus, Luís (1994). A Concepção Nobiliárquica do Espaço Ibérico. Geografia dos Livros de Linhagens Medievais Portugueses (1280-1380). Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian e JNICT. [ Links ]

Leão, Duarte Nunes de (1975 a). Crónica de D. João I; In Tesouros da Literatura e da História, Crónicas dos Reis de Portugal. Porto: Lello & Irmãos. [ Links ]

Leão, Duarte Nunes de (1975 b). Crónica de D. Duarte. In Tesouros da Literatura e da História, Crónicas dos Reis de Portugal. Porto: Lello & Irmãos [ Links ]

Leão, Duarte Nunes de (1975 c). Crónica e vida del Rey D. Affonso o V. In Tesouros da Literatura e da História, Crónicas dos Reis de Portugal. Porto: Lello & Irmãos [ Links ]

Lima, Jacinto Leitão Manso de (2008). Famílias de Portugal. Lisboa: Casa da Prova, Tomo I. [ Links ]

Livro de Linhagens do Conde D. Pedro(1980). (Ed. crítica por José Mattoso). In Portugaliae Monumenta Histórica, Nova Série, vol. II, Lisboa: Academia das Ciências. [ Links ]

Livro de Linhagens do Séc. XVI (1956). Fontes Narrativas da História Portuguesa, nº 3 (Introdução de António Machado de Faria), Lisboa: Academia Portuguesa de História. [ Links ]

Livro dos Copos (2006). In Militarium Ordinum Analecta, nº 7, vol. I, (introdução de Paula Pinto Costa; Maria Cristina Pimenta e Isabel Morgado Sousa e Silva), Porto, Fundação Engº António de Almeida. [ Links ]

Livro dos forais, escripturas, doações, privilégios e inquirições(1946-1948). Subsídios para a história da Ordem de Malta, II-IV, 3 vols., (prefácio de José Mendes da Cunha Saraiva) Lisboa: Arquivo Histórico do Ministério das Finanças. [ Links ]

Lopes, Fernão (1966). Crónica de D. Fernando, nono rei destes regnos. (Introdução de Salvador Dias Arnaut), Biblioteca HistóricaSérie Régia. Porto: Livraria Civilização. [ Links ]

Lopes, Fernão (1983). Crónica de D. João I, (intr. de H. B. Moreno e prefácio de António Sérgio). Porto: Liv. Civilização. [ Links ]

Lopes, Fernão (1986). Crónica de D. Pedro I, (intr. de Damião Peres). Porto: Liv. Civilização. [ Links ]

Marques, José (1990). D. Afonso IV e as suas jurisdições senhoriais. In Actas das II Jornadas Luso-Espanholas de História Medieval, vol. IV, Porto: INIC:1527-1566. [ Links ]

Mascarenhas, D. Jerónimo de (1918). Historia de la Ciudad de Ceuta, sus sucessus militares y politico; memorias de sus santos y prelados y elogios de sus capitanes generales (1648), (pub. por Afonso de Dornelas), Lisboa: Academia das Ciências. [ Links ]

Mata, Joel da Silva Ferreira (1991). Alguns aspectos da Ordem de Santiago no tempo de D. Dinis. In As Ordens Militares em Portugal, Actas do 1º Encontro Sobre Ordens Militares. Palmela: Estudos Locais/C. M. Palmela: 205-217. [ Links ]

Mata, Joel Silva Ferreira (2007). A Comunidade Feminina da Ordem de Santiago: a Comenda de Santos na Idade Média. In Militarium Ordinum Analecta, nº 9, Porto: Fundação Engº António de Almeida. [ Links ]

Mattoso, José ( 1985). A nobreza e a revolução de 1383. In Actas das Jornadas de História Medieval 1383-1385 e a crise geral dos séculos XIV/XV: 391-402; [ Links ]

Mattoso, José (1993). Dois Séculos de Vicissitudes Políticas. O Triunfo da Monarquia, in História de Portugal. A Monarquia Feudal, vol. 2: 149-155. [ Links ]

Monumenta Henricina(1960-1974). Comissão Executiva das Comemorações do V Centenário da Morte do Infante D. Henrique. 15 vols., Coimbra: Atlântida,. [ Links ]

Monumenta Portugaliae Vaticana(1968-1970-1982). (Introduçãoe notas de António Domingues de Sousa Costa), 5 vols., Braga: Livraria Editorial Franciscana. [ Links ]

Morais, Cristóvão Alão de (1943). Pedatura Lusitana., Porto: Livraria Fernando Machado. 6 Tomos. [ Links ]

Moreno, Humberto Carlos Baquero (1979). A batalha de Alfarrobeira. Antecedentes e significado histórico. Coimbra: Biblioteca geral da Universidade de Coimbra. [ Links ]

Moreno, Humberto Carlos Baquero (1988). Contestação e posição da nobreza portuguesa ao poder político nos finais da Idade Média. In Ler História, nº 13: 3-14. [ Links ]

Moreno, Humberto Carlos Baquero (1987). Exilados portugueses em Castela durante a crise dos finais do século XIV (1384-1388). In Actas das II Jornadas Luso Espanholas de História Medieval, vol. I, Porto: 69-101. [ Links ]

OOcallaghan, J. F. (1975). Definiciones of the Order of Calatrava enacted by Abbot William II of Morimond, April, 2, 1468. In The Spanish Military Order of Calatrava and its affiliates, Collected studies, London. [ Links ]

Oliveira, Luís Filipe Simões Dias de (2006). A Coroa, os Mestres e os Comendadores: As Ordens Militares de Avis e de Santiago (1330-1449). Faro: Edição poli copiada (Dissertação de Doutoramento em História Medieval apresentada a Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais da Universidade do Algarve). [ Links ]

Ordenações Afonsinas(1984). (Nota de apresentação de Mário Júlio de Almeida Costa e nota textológica de Eduardo Borges Nunes), Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 5 vols. [ Links ]

Ordenações del-Rei D. Duarte(1988). (Edição preparada por Martim de Albuquerque e Eduardo Borges Nunes), Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. [ Links ]

Ordenações Manuelinas(1984). (Nota de apresentação de Mário Júlio de Almeida Costa), Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 5 vols. [ Links ]

Osório, D. Jerónimo (1944). Da vida e feitos de El-rei D. Manuel. Porto: Livraria Civilização, 2 vols. [ Links ]

Pimenta, Maria Cristina (2001). As Ordens de Avis e de Santiago na Baixa Idade Média: O Governo de D. Jorge. In Militarium Ordinum Analecta, nº 5, Porto: Fundação Eng. António de Almeida. [ Links ]

Pimenta, Maria Cristina (2005). D. Pedro I. Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores. [ Links ]

Pina, Rui de (1977a). Crónica D. Sancho I, In Tesouros da Literatura e da História (introdução e revisão de M. Lopes de Almeida). Porto: Lello & Irmão. [ Links ]

Pina, Rui de (1977b). Crónica D. Afonso II, In Tesouros da Literatura e da História (introdução e revisão de M. Lopes de Almeida). Porto: Lello & Irmão. [ Links ]

Pina, Rui de (1977c). Crónica D. Sancho II, In Tesouros da Literatura e da História (introdução e revisão de M. Lopes de Almeida). Porto: Lello & Irmão. [ Links ]

Pina, Rui de (1977d). Crónica D. Afonso III, In Tesouros da Literatura e da História (introdução e revisão de M. Lopes de Almeida). Porto: Lello & Irmão. [ Links ]

Pina, Rui de (1977e). Crónica D. Dinis, In Tesouros da Literatura e da História (introdução e revisão de M. Lopes de Almeida). Porto: Lello & Irmão. [ Links ]

Pina, Rui de (1977f). Crónica D. Afonso IV, In Tesouros da Literatura e da História (introdução e revisão de M. Lopes de Almeida). Porto: Lello & Irmão. [ Links ]

Pina, Rui de (1977g). Crónica D. Duarte, In Tesouros da Literatura e da História (introdução e revisão de M. Lopes de Almeida). Porto: Lello & Irmão. [ Links ]

Pina, Rui de (1977h). Crónica D. Afonso V, In Tesouros da Literatura e da História (introdução e revisão de M. Lopes de Almeida). Porto: Lello & Irmão. [ Links ]

Pina, Rui de (1977i). Crónica D. João II. In Tesouros da Literatura e da História (introdução e revisão de M. Lopes de Almeida). Porto: Lello & Irmão. [ Links ]

Pizarro, José Augusto de Sotto Mayor (1999). Linhagens medievais portuguesas: genealogias e estratégias, 1279-1325. (Pref. de José Mattoso), Porto: Universidade Moderna / Centro de Estudos de Genealogia, Heráldica e História da Família, 3 vols. [ Links ]

Pizarro, José Augusto de Sotto Mayor (2005). D. Dinis, Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores. [ Links ]

Pizarro, José Augusto de Sotto Mayor (2006). The Participation of the Nobility in the Reconquest and in the Military Orders. In e-JPH, vol. 4, number I, Summer 2006, pp. 1-10. Disponivel em (http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Portuguese_Brazilian_Studies/ejph/html/issue7/html/jpizarro_main.html) [ Links ]

Resende, Garcia de (1973). Crónica de D. João II e miscelânea. (Introdução de Joaquim Veríssimo Serrão) Lisboa: INCM. [ Links ]

Sá, Aires de (1899). Fr. Gonçalo Velho. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional,. 3 vols. [ Links ]

Santarém, Visconde de (1842-1876). Quadro Elementar das relações politicas e diplomaticas de Portugal com as diversas potencias do mundo desde o principio da monarchia portuguesa athe aos nossos dias. Paris: J.P. Ailaud, tomos I-XVIII. [ Links ]

Silva, Isabel Luísa Morgado de Sousa e (2002). A Ordem de Cristo (1417-1521). In Militarium Ordinum Analecta, nº 6, Porto: Fundação Eng. António de Almeida. [ Links ]

Silva, Isabel Luísa Morgado de Sousa e, (2002 b). As comendas novas da Ordem de Cristo no Entre Douro e Minho. In Actas do I Congresso sobre a Diocese do Porto Tempos e Lugares de Memória, Porto: [s.l.], vol. II, 43-71. [ Links ]

Sousa, D. António Caetano de (1946-1954). Provas de História Genealógica da Casa Real Portuguesa. 2ª edição (revista por M. Lopes de Almeida e César Pegado). Coimbra: Atlântida Livraria Editora, 6 vols. em 12 tomos. [ Links ]

Sousa, D. António Caetano de (1946-1955). História Genealógica da Casa Real Portuguesa. 2ª edição, Coimbra: Atlântida Livraria Editora, 14 vols. [ Links ]

Sousa, Manuel de Faria e (1681). Africa portuguesa. Lisboa: Antonio Craesbeeck de Mello. [ Links ]

Soveral, Manuel Abranches de (1998). Sangue Real. As nossas ascendências à Casa Real Portuguesa. Porto: MASmedia. [ Links ]

Soveral, Manuel Abranches de (2004). Ascendências Vianenses. Ensaios genealógicos sobre a nobreza de Viseu. Séc. XIV a XVII, 3 vols., Porto: Edição do Autor. [ Links ]

Soveral, Manuel Abranches de; Mendonça, Manuel Lamas de (2004). Os Furtados de Mendonça portugueses. Ensaios sobre a sua verdadeira origem, [s.l.]: Edição do Autor. [ Links ]

Soveral, Manuel Abranches do (s.d). Ensaio sobre a origem dos Correa, senhores de Fralães. Séculos XIV e XV. Disponível em (http://pwp.netcabo.pt/soveral/mas/Correia.htm) [ Links ]

Soveral, Manuel Abranches do (s.d). Leitão. Origens e ascendências do paço de Figueiredo das Donas. Disponível em (http://pwp.netcabo.pt/soveral/mas/Leitao.htm) [ Links ]

Soveral, Manuel Abranches do (s.d.). Os filhos e netos do muj honrrado barom Dom Frei Lopo Dias de Sousa, 8º mestre da Ordem de Cristo. Disponível em (http://pwp.netcabo.pt/soveral/mas/SousaArronches.htm) [ Links ]

Teixeira, André Pinto de Sousa Dias (2004). Uma linhagem ao serviço da <<ideia imperial Manuelina>>: Noronha e Meneses de Vila Real, em Marrocos e na Índia. In Actas do Colóquio Internacional A Alta Nobreza e a Fundação do Estado da Índia. Lisboa: C.H. de Além mar/U.N.L./I.I.C.T./C.E.H.C.A.: 109-174. [ Links ]

Thomaz, Luís Filipe F.R. (1998). De Ceuta a Timor, 2ª Ed., Miraflores: Edifel. [ Links ]

Vasconcelos, António Maria Falcão Pestana de (2008). Nobreza e Ordens Militares. Relações Sociais e de Poder (séculos XIV a XVI). Porto: Edição policopiada, 2 vols. (Dissertação de Doutoramento em História apresentada à Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto). [ Links ]

Zurara, Gomes Eanes de (1899). Chronica de El-Rei D. João I. Lisboa: Bibliotheca de Classicos Portuguezes, Escriptorio, 3 vols. [ Links ]

Zurara, Gomes Eanes de (1915). Crónica da Tomada de Ceuta por El Rei D. João I. (Edição de Francisco Maria Esteves Pereira), Lisboa, Academia das Ciências. [ Links ]

Zurara, Gomes Eanes de (1992). Crónica da Tomada de Ceuta. (Introdução e notas Reis Brasil), Lisboa: Europa-América. [ Links ]

Zurara, Gomes Eanes de (1978). Crónica do Conde D. Duarte de Menezes. (Edição diplomática de Larry King), Lisboa: Universidade Nova / Faculdade Ciências Sociais e Humanas,. [ Links ]

Zurara, Gomes Eanes de (1988). Crónica do Conde D. Pedro de Meneses. (Apresentação por José Adriano de Freitas Carvalho), Porto: Programa Nacional de Edições Comemorativas dos Descobrimentos Portugueses. [ Links ]

Notes

2Of these studies, attention is drawn to the Ph.D. dissertations presented at the Faculty of Letters of the University of Porto in 1998 (Silva 2002) and 1999 (Costa 1999/2000: 3-592) (Pimenta 2001: 3-600) (Mata 2007). Besides these studies, there are also two other Ph.D. dissertations, the first defended at the Faculty of Letters of the University of Porto, in 2004 (Ferreira 2004) and the second presented at the Faculty of Human and Social Sciences of the University of the Algarve, in 2006 (Oliveira, 2006).

3Barros 1998; Castanheda 1979; Correia 1974: 4 vols.; Góis 1926; Góis 1790; Leão 1975; Lopes 1966; Lopes 1983; Lopes 1986; Mascarenhas 1918; Osório 1944: 2 vols.; Pina 1977; Resende 1973; Sousa 1681; Zurara 1899: 3 vols.; Zurara 1915; Zurara 1992; Zurara 1978; Zurara 1988.

4Livro de Linhagens do Conde D. Pedro, 1980; Livro de Linhagens do Séc. XVI, 1956; Castelo Branco 1974: vol. 48-49; Gayo 1938-1941; Lima 2008; Morais 1943; Sousa 1946-1955; Soveral 1998; Soveral 2004; Soveral (http://pwp.netcabo.pt/soveral/mas/Correia.htm); Soveral (http://pwp.netcabo.pt/soveral/mas/Leitao.htm); Soveral (http://pwp.netcabo.pt/soveral/mas/SousaArronches.htm); Soveral and Mendonça 2004.

5The lineages studied were those of the following noble families: de Abreu; de Almeida; Ataíde; de Azevedo; Barreto; de Brito; de Castelo Branco; Castro/Eça; Coelho; Correia (Fralães); Coutinho; Cunha (Albuquerque); de Faria; Freire de Andrade; Furtado de Mendonça (Lencastre); de Góis; Henrique; Leitão; de Mascarenhas; de Melo; de Meneses; de Miranda; Moniz; de Noronha; Pereira; de Sá; de Sequeira; da Silva; de Sousa (Arronches and Prado); Tavares; de Távora; and de Vasconcelos.

6Cunha 1997: 377.

7Cunha 1997: 378.

8Cunha 1997: 123.

9Mata 1991: 208.

10Pimenta 2001: 35. Pizarro 2005: 104-105 and 164-165. Almeida 1967-1971: I, 150-152; Cunha 1991: 156-169.

11On Dom Dinis involvement in the process leading to the creation of the Order of Our Lord Jesus Christ, see Pizarro 2005: 165-166.

12Mattoso 1993: II, 158-161.

13Figueiredo 1800: II, 310 and ff.; Costa 1999/2000: 189.

14Costa 1999/2000: 189 and 191.

15Costa 2001: 174.

16Pimenta, 2001: 36.

17Mattoso 1993: II, 489-490. Coelho 2005: 16-17.

18Lopes 1966: cap. CXLI.

19Pimenta 2001: 36.

20Pimenta 2001: 37.

21Silva 2002: 27-28; Freire 1927: I, 88; II, 247.

22Marques 1990: IV, 1527-1566.

23On the social and political importance of the lineage of the Pereiras, in relation to both the monarchy and the Order of the Hospital, see Krus 1994: 140-141 and notes 298, 299 and 300.

24This prior was momentarily relieved of the priorship, after having revealed his intention to switch allegiance to the side of Castile (1396). He was temporarily replaced by Lourenço Esteves de Góis. This situation was resolved in 1398, as a result of the intervention of the Constable of the realm, Dom Nuno Álvares Pereira (Leão 1975a: cap. LXXVII, 646-647, cap. LXXIX, 655, and cap. LXXX, 657-658).

25Pimenta 2001: 64; Silva, 2002: 99.

26Silva 2002: 95.

27Costa 1999/2000: 222-224.

28Costa 2005: 77.

29Costa 1999/2000: 569-579.

30AN/TT., Gaveta VII, maço 6, nº 1. Cf. Almeida 1967-1971: II, 217.

31For the Order of Christ, the important moment was the charter dated May 19, 1426, Pub. Monumenta Henricina, III, doc. 60: 112-115. Regarding the rules that were to be followed in drawing up these wills, see Vasconcelos 1998: 14, note 6.

32For the Order of Santiago, see Cunha 1991: 191-192; UCBG - R-31-20, Regra, statutos e diffinções da Ordem de Santiago de 1509, fl. 3. In the case of the Orders of Christ and Avis, the fulfillment of this vow was altered in June 1496, when, through the intervention of Dom Manuel, Pope Alexander VI gave permission for the friar-knights and commanders of these militias to marry. Papal Bull Romani pontificis sacri apostolatus, of June 20, 1496 (Sousa 1946-1954: t. II, 1ª pt, 326-328).

33For more details on this troubled moment in the kingdom, see the studies by Ferro 1983: 45-89; Mattoso 1985: 391-402; Arnaut 1986: 11-33; Moreno 1987: 69-101; Moreno 1988: 3-14; Cunha 1996: 119-252; Fernandes 1996. On the subject of Dom Fernando and the Peninsular War, see also Ayala Martinez and Villalba Ruiz 1989: 233-245.

34On this political moment, see Moreno 1979: I, 99-145 and 266-303; Gomes 2005: 64. Corte-Real 2004.

35Cunha 1990: 167-173; Fonseca 2005: 66-72.

36On this subject, see, amongst others, Freire 1996, III; Teixeira 2004, 109-174.

37There were several noble families that benefited from their members being awarded knighthoods, after the conquest of Ceuta (1415), in recognition of the services that they had provided in battle, most notably the royal family itself with the princes Dom Duarte, Dom Pedro and Dom Henrique (Zurara 1915: cap. XCVI), and the lineages of the following families: Gomide (Zurara 1915: cap. LXXVI); de Albergaria; de Abreu; de Almada; de Almeida; de Ataíde; de Azevedo; de Bragança; de Castelo Branco; Correia; da Cunha; Mascarenhas; de Meneses; de Noronha; Pereira; de Seabra; de Sequeira; da Silva; da Silveira; and de Travaços (Zurara 1915: cap. XCVI). Those rewarded with noble titles after the conquest of Alcácer Ceguer (1458) included the following families: Bragança (Freire 1996: III, 290-291; 291-292; 326-327), de Castro (Freire 1996: III, 280-281), de Meneses (Freire 1996: III, 281-285; 287-289) and de Melo (Freire 1996: III, 289). Those rewarded with noble titles after the conquest of Arzila and Tangier included the following families: Bragança (Freire 1996: III, 299-300), de Castro (Freire 1996: III, 292-293), Coutinho (Freire 1996: III, 310), Galvão (Freire 1996: III, 295-296), de Meneses (Freire 1996: III, 287-289), and de Vasconcelos (Freire 1996: III, 293-294).

38Those rewarded with noble titles after their participation in the Peninsular War (1475-1479) included the following families: de Albuquerque (Freire 1996: III, 307-310), de Almeida (Freire 1996: III, 317-322), de Lima (Freire 1996: III, 81-84 and 316-317), de Melo (Freire 1996: III, 324-325), de Meneses (Freire 1996: III, 327-328), Pereira (Freire 1996: III, 330-332), Silveira (Freire 1996: III, 300-307), and de Sotomaior (Freire 1996: III, 322-324).

39On the House of Bragança, see: Cunha 1990.

40Godinho 1962.

41Cunha 2004: 304.

42Sousa 1946-1955: V, 291-293.

43Examples of this were the House of Vila Real and Alcoutim (Noronha), which held the captaincy of the city of Ceuta, the House of Tarouca (Meneses), which held the captaincy of the fortresses of Arzila and Tangier, and the House of Redondo (Coutinho), which held the captaincy of the fortress of Arzila.

44In relation to this subject, see what is said by Costa 2000: 34. In reality, the only titled member of the nobility to go to India was Dom Vasco da Gama in 1524, when he undertook his third voyage.

45Costa 2005: 170.

46For the period of the fourteenth century, see Oliveira 2006: 15.

47By way of example, we could mention the following families: de Abreu, de Almeida, Barreto, Correia, Freire de Andrade, Furtado de Mendonça, de Mascarenhas, de Miranda, Moniz, de Noronha, and de Vasconcelos.

48The exceptions were the following families: de Almeida, Correia and Freire de Andrade, who mainly showed a preference for other institutions. Those families that showed their preference for the Order of Santiago for the first time were: Henrique, Pereira, de Meneses, and de Sá.

49Freire 1996: III, 201; Sousa, 1946-1954: XII, 174; Guimarães 1916: 71-97.

50I am referring here specifically to the reform introduced by Dom João Vicente, Bishop of Lamego, at the request of Prince Henry the Navigator, which was approved by the Pope, as can be seen by the Papal BullSuper gregem dominicum, of November 22, 1434. Monumenta Henricina, vol. V, doc. 49: 113-115.

51Amongst others, these included: Gonçalo Vaz Coutinho, commander-in-chief of the Order of Christ, accompanied by 20 horsemen and 30 foot soldiers (AN/TT., Chancelaria de D. Afonso V, Liv. 27, fl. 133. Pub.Chancelarias Reais, Tomo I, doc. 168, p. 205.); Diogo Lopes de Faro, knight and commander of Castro Marim (AN/TT., Chancelaria de D. Duarte, Liv. 1, fl. 230v); Fernão Lopes de Azevedo, knight and commander of Casével (Pina 1977g: cap. XXVI and cap. XXVII: 147-151; Leão 1975b: cap. XI, 758; Moreno 1980: 563 and 731-732); Gonçalo Rodrigues de Sousa, commander of Nisa, Montalvão, Alpalhão and Idanha, captain of the Ginetes, who had 300 horsemen under his command (Leão 1975b:cap. X, p. 756 and cap. XI, p. 758; Pina 1977g: 155 and 160).

52On the conquest of Alcácer Ceguer and the activities of Prince Henry the Navigator, see the description made by Pina 1977h: caps. CXXXVIII and CXLII. The active participation of the Order and its governor throughout the course of this process had, as its corollary, the donation made by the monarch to the Order of Christ of the right of patronage over this town, along the same lines as the one that it enjoyed in Tomar.Monumenta Henricina, vol. XIII, doc. 87, 152-153.

53The Infante Dom Fernando was appointed administrator of the mastership of the Order of Christ for life by Pope Pius II, through the Letter Repetentes animo, dated July 11, 1461. Pub. Monumenta Henricina, vol. CIV, doc. 57, 158-162.

54At the request of Dom Afonso V, Pope Paul II, through the letter Dum regalis of February 1, 1471, granted the mastership of the Order of Christ to Dom Diogo for life.Monumenta Henricina, vol. XV, doc. 6, 7-9.

55Pina 1977i: cap, XVIII; Resende 1973: cap. LIV. On this subject, see also Silva 2002: 91, note 339.

56Vasconcelos 2008: 173-181.

57These families included: de Brito, granted command of the benefice of Castelo Novo; de Castelo Branco, responsible for the administration of Pindo; de Castro, given control of the benefices of Segura and Cardiga; Coutinho, given ownership of the benefices of Trancoso, Almourol, Alpalhão, Portalegre, Anciães, Touro and Rosmaninhal; da Cunha, given the benefices of Castelejo and Castelo Novo; Freire de Andrade with the benefice of Lousã; Leitão, with the benefice of São Vicente da Beira; Meneses with Mendo Marques and Penamacor; de Miranda, with Torres Vedras and Santa Maria de Póvos; Pereira, with Casével; da Silva, with the benefices of Ferreira, Soure, Marmeleiro and Reigada; de Sousa (Arronches), with Idanha, Niza and Soure; de Sousa (Prado), with the benefices of Redinha, Segura, Lardosa, Santa Ovaia, Jejua, Salvaterra, Ega, Niza, Idanha, Rates and Arruda.

58SILVA, 2002 b, p. 48.

59This group included, for example, the following families: de Abreu, de Ataíde, de Azevedo, de Brito, Castro/Eça, Coelho, Coutinho, Cunha/Albuquerque, de Faria, Góis, Henriques, de Melo, de Meneses, Moniz, de Noronha, Pereira, de Sá, Sequeira, da Silva, Sousa (Arronches) and (Prado), Tavares, Távora, and de Vasconcelos.

60This was the case with the following families: de Almeida, Barreto, Furtado de Mendonça and Mascarenhas.