Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

e-Journal of Portuguese History

versão On-line ISSN 1645-6432

e-JPH v.8 n.1 Porto 2010

The military in the Chamber of Deputies 1851-1870corporative lines of action in defense of the army

Isilda Braga da Costa Monteiro1

1CEPESE –Center for Studies on the Population, Economy and Society. E-mail:isildamonteiro@bragadacosta.com

Abstract

Based on our reading of the minutes of the parliamentary sessions, we shall attempt in this study to analyze the performance of army officers in the Chamber of Deputies, which, from 1851 to 1870, represented one of the most important settings for the militarys participation in politics.

Keyword

The military; Political participation; Parliament; Regeneration; Army.

Resumo

No presente estudo, procuraremos analisar, através da leitura das actas das sessões, a actuação dos oficiais do Exército na Câmara dos Deputados que, entre 1851 e 1870, se assume como um dos principais espaços da participação política dos militares.

Palavras-chave

Militares; Participação política, Parlamento, Regeneração, Exército

Introduction

Only very recently has the study of the relationship between the military and political power begun to gain its own space in Portuguese historiography.2 Prior to this, the political participation of members of the armed forces had frequently been regarded as a mere episode adorning the scenery of Portuguese history over the last two centuries, denying it the power to explain much of what had effectively influenced and conditioned its development. In fact, in Portugal, as in other countries, the military were characterized in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries by their heavy involvement in politics, which fits in with the various descriptions made of the phenomenon by Abrahamson, ranging from lobbying to armed conflict, passing through the defense, in the press, of corporative or markedly political positions (1985: 258-259).

However, based on the analysis of military interventionism, which is more attractive for historians because of the dynamics and the breaks with the past that it implies, the studies published on this question clearly emphasize two distinct periods in the nineteenth centurythe first one stretching from the time of the French invasions until 1851 and the second one running from the ultimatum to the end of the monarchy. In between these two periods are four decadesfrom 1851 to 1890generally referred to as the period of the Regeneration, linked to concepts such as national reconciliation, rotation, regenerating peace, material development and progress. It was concepts such as these that gave shape to the myth of unitary Regeneration (SARDICA, 1997b: 560), which is itself responsible for the little that is known about each of the phases that marked that period of nineteenth-century national history and, in particular, the first of these, which began in 1851.

In this study, we shall attempt, through our reading of the minutes of the parliamentary sessions, to analyze the performance of the military in the Chamber of Deputies, which, from 1851 to 1870, represented one of the main aspects of the militarys participation in politics. Presented as the moment that marked the armys return to the barracks in the nineteenth century and its unification in what has come to be regarded as the domestication of the military (SARDICA, 1997a: 291), the Regeneration seems to correspond to a time of lesser involvement on the part of the military after several decades of heavy conflict. During the first half of the nineteenth century, the struggle for power and the existence of specific problems related to the functioning of the military institution (particularly promotions, which, in a period of instability, reflected the evolution of the political conflicts themselves) that contributed towards the army being caught in a vicious circle that could only be brought to an end through the stabilization, strengthening and cohesion of the State (MARQUES, 1996: 19). As has already been said by other authors, in the first decades of the nineteenth century, the political question became a military question, at the same time as the military question itself became a central political question (MARQUES, 1999: 119). Taken together, such aspects justify the leading role played by the army during the first half of the nineteenth century, arising from its profound politicization, which had as its immediate consequence the appearance of the soldier-politician, always on the lookout for the right moment to intervene militarily with the support of the troops under his command.

The uprising led by Saldanha in April 1851 marked the turning point in this situation, which had maintained the country in a state of constant upheaval. The greater political, economic and social stability that characterized the first phase of the Regeneration just beginning at that time brought about an at least similar reduction in the preponderance of the army and its soldiers in the running of national political life, leading them to abandon armed military interventionism, while at the same time diminishing the phenomenon of militarization which had indelibly marked the first half of the nineteenth century. The ideological confrontation that had characterized the long post-revolutionary phase had begun to flag. The prevailing interests and objectives were now quite different ones.

It is within this new political framework that we shall attempt to learn more about the political profiles of the military personnel who, while not ceasing to engage in politics due to the abandonment of the revolutionary path, began to behave as political beings through the political mechanisms enshrined in civil society (CAEIRO, 1997: 61) in parliament, regulated by the parliamentary mechanisms in force. The achievement of their aims now depended not on the force of arms, but on their capacity to represent, in the Elective Chamber, the group and institution to which they belonged and on their political performance, the most visible expression of which is the political discourse that was produced in the room where the sessions were held and transcribed in the minutes that we shall now use as our source.

In our analysis, we shall consider two theoretical premises relating to the military institution that will enable us to understand the specificity of the presence and involvement of army officers in the Chamber of Deputies, between 1851 and 1870. The first premise is that the political participation of the military is favoredalthough this phenomenon does not operate by itselfby the symbolic power that they enjoy and which results, above all, from the fact that they are the legitimate holders of a monopoly of violence and, as such, are in the possession of weapons, and of men with the technical knowledge needed to use them. Furthermore, the heavy intra-organizational socialization that characterizes the military institution makes it possible for them to strengthen their identity by internalizing values and attitudes such as the sense of discipline and cooperation and, above all, the esprit de corps, which allow soldiers to set themselves up as a separate social category, building a class identity without actually amounting to a class, and therefore encouraging the lessening, or even the disappearance, of the distinguishing marks of the multi-class composition that characterizes them (MARQUES, 1999: 99). These were aspects that, at the beginning of the second half of the nineteenth century, either did not exist in other socio-professional groups or, if they did, only existed in a very incipient and rudimentary form.

The second premise, about which there is less agreement, is based on the principle that with the armys increasing openness to the middle classes and its growing professionalization throughout the nineteenth century (in Portugal, it had been possible since 1792 for those who were not the holders of titles to embark upon a military career in the army (CARRILHO, 1985: 122), which was required by the development of war technology (and, in the Portuguese case, of the political and military vicissitudes that had marked the first two decades of the nineteenth century), there had been a greater political involvement of the military, gradually bringing an end to the aristocratic tradition that had placed them above politics and obliged them to seek the support of other elites in order to achieve their political aims.2

Consideration of these premises lends another dimension to the evident political involvement of the military in parliament during the Regeneration. An involvement that cannot be justified solely by the mere personal ambition of the men themselves, although it is to be noted that, in the specific case of the military, a parliamentary seat could represent subsequent appointment to important posts of command or to committees under the direct supervision of the ministries, in particular the Ministry of War and the Ministry of Public Works. Nor can it be understood either as the exclusive result of the instrumentalization of the army and the military by the government, factions or political parties, thereby undermining their own autonomy and will. Studying the parliamentary sessions through the reading and analysis of the respective minutes enabled us to detect specific lines of action on the part of the military deputies. Such details show us that the military were also in parliament because they knew that just as had been the case in the first half of the nineteenth century when they had appeared there with their weapons in their hands under the command of such charismatic leaders as Terceira, Saldanha, Sá da Bandeira or Bonfim (VALENTE, 1997: 58) in order to implement revolts and uprisings, so, in the second half of the same century, the survival of the institution to which they belonged again depended, without any visible alternative, upon their proximity to the political power. Survival of this nature would be difficult in a regime that, in essence, was hostile towards them, since liberalism was intrinsically antimilitaristic (HUNTINGTON, 1972: 90-91). This obliged the military institution to rethink its existence, to legitimize itself and to reconstruct itself based on new premises, new raisons dêtre, which were to be sought after in the new national and international political reality. This was naturally a complicated task in a country of undisputed borders in its continental version, whose main interest was in turning the page of history and paving the way towards national reconciliation. More than ever, the army, and above all the material and human costs involved in maintaining the military institution, seemed at such a time to be an unnecessary evil, justifying the voices raised in the press by those who stressed its uselessness in the face of a political power that both could not and would not listen to them. For two main reasons.

On the one hand, although it was intrinsically antimilitaristic in nature, liberalism in Portugal owed a debt to the army and its members, who, at the different moments in the first half of the nineteenth century when the regime was called into question, had always come out in its defense. A debt that the regime recognized and that was strategically and repeatedly stressed by the members of the military with seats in parliament, seeking to repay it by introducing the reforms that the army needed in order to promote its identification with the Nation and, in this way, to define its space within the national reality. On the other hand, the weapons and the men that were in the possession of the army allowed it to keep open the dangerous possibility of the revolutionary path, and this was something that the political power could not permit, since it was aware that neither the country nor the liberal regime could continue to tolerate the social and political instability that had led to its exhaustion and breakdown in the first half of the nineteenth century. Conscious of this reality, both young and old army officers alike took up seats in the Chamber of Deputies after 1851, ready to respond to the political expectations placed in them by the party leaders, but equally ready to make sure that the voices of their comrades and the institution that they served could be properly heard in that arena of power. Thus, regardless of the political faction that they supported, our reading of the parliamentary proceedings has enabled us to detect the main lines of action of the military in the Chamber of Deputies, which we shall now present.

1. The military in the Chamber of Deputies

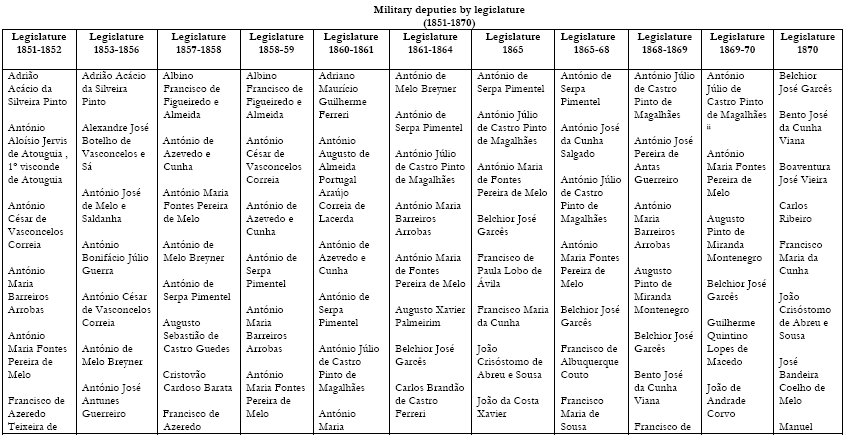

There were many military figures who were members of the Chamber of Deputies between 1851 and 1870 [see APPENDIX I], with the particularity that those who were in active service were able to combine their parliamentary duties with service in their units or at military offices. Covering the whole hierarchical echelon of the military leadership, there were to be found at the Chamber of Deputies not only high-ranking officers, such as, for example, brigadier Augusto Xavier Palmeirim, the retired field marshal, João da Costa Xavier, the brigadier general, promoted in 1864 to field marshal, the Baron of the River Zêzere, but also officers at the beginning of their careers who were younger (with ages ranging between 30 and 40) and had limited military experience but a high level of technical training, such as lieutenant João Nepomuceno de Macedo, captain Guilherme Quintino Lopes de Macedo or lieutenant Fernando Luís Mousinho de Albuquerque. Thus, in the main chamber of power, there were to be found, sitting side by side, high-ranking officers from the army with a knowledge that had been built up over years of service and an experience accumulated in the many battles that had marked the first half of the nineteenth century, under the hail of bullets and pressure from the enemy, and promising subordinates just starting out in their careers, with a new way of seeing and feeling the army.

The identification of the military deputies, whether in active service or in a retirement situation (thus excluding all those who, having begun a career in the army had either been dismissedas was the case with Afonso Botelho de Sampaio e Sousa and Marcos Torres Vaz Freireor had voluntarily abandoned the armed forces, such as Frederico Augusto Ferreira, Rodrigo José de Meneses Ferreira de Eça, the Count of Cavaleiros, António de Sousa Sampaio, Raimundo Correia Pinto Tameirão, the Baron of Valado, José Mesquita da Rosa, José Maria dos Santos and Luís de Almeida Coelho de Campos), regardless of the time when they began or finished their mandate in a certain legislature,4 enabled us to form a more precise idea of their presence in the Chamber throughout the period under consideration.

In the legislature of 1853-1856, 36 members of the military entered parliament, many of them passing through the doorway opened by Saldanha for the first (and, in some cases, the last) time. Seeking to strengthen his position in what was one of the most important organs of powerparliamentSaldanha mobilized some of his most faithful followers in the ranks of the army and caused them to take seats in the Chamber of Deputies. Transformed into a hotbed from which the government could recruit the men that it needed for performing the most diverse political, technical or administrative roles, the army and the members of the armed forces were now at the very centre of attention. A fact that not all of them seemed to accept. In 1854, when the great controversy arose about the accumulation of administrative and military functions in an army general who was to be appointed governor of Madeira, the deputy José Maria de Abreu claimed, there was a time when the toga was considered to be most important, today it is the sword. (...) at this moment, I am pleased to show my respect and veneration for the distinguished men who honor the Portuguese army, and to prove that this is indeed the case all one needs to do is to look at the colleagues around us, but (...) a soldier must be a complete soldier in the performance of his functions, and these are very serious and important.5 Abreu thus referred to the contradiction that the Regeneration had fallen into by, on the hand, attempting to send the soldiers back to the barracks and thus keeping them away from revolutionary temptations, and, on the other hand, seeking to gain from them the support that it needed, placing them within its political orbit, supplying the needs of a state machine for which the professional profile had not yet been defined. While this could be understood as a strategy for military control, it certainly brought with it certain risks, by affording soldiers a leading role in a situation that would always have unpredictable results.

In fact, even after Saldanha had been removed from power in 1856, the military continued to be present in the Chamber in significant numbers, although they were understandably fewer in total than in the period between 1853 and 1856. For the decade from 1858-1859 to 1868-1869, the presence of the military in the Chamber of Deputies amounted to between 20 and 27 deputies. Following on from one another during that period, at different times and representing different political factions, were three highly respected army officers, Loulé, Terceira and Sá da Bandeira, and two civilians, Joaquim António de Aguiar and António José de Ávila. Finally, the last two legislatures (in Sá da Bandeira and Loulé, they recovered the leadership of the government) were characterized by the reduced presence of the military in the Elective Chamber when compared with the numbers recorded previously: 16 deputies in 1869-1870 and 11 in 1870 [see APPENDIX I].

Thus, by forming a socio-professional group of a significant size at the Chamber of Deputies during the period under consideration, between 1851 and 1869, the members of the military took a leading role on the parliamentary stage. Adjusting their activities and their discourse to strengthening the armys identification with the Nation, these men turned the military question into an important political question within the Chamber of Deputies, always placing it on the parliamentary agenda for discussion whenever possible. They brought an end to the previous image of military men as relatively unskilled speakers and, as such, people of fairly limited impact in political and parliamentary circles (MARQUES, 1999: 275), replacing this picture with another more dynamic and more active image. In a criticism published in 1858, which was leveled against the parliament and the deputies who composed the legislature, the author included in the restricted group of thirteen deputies that he considered worthy of the title of parliamentary speakers two military men, captain António de Serpa Pimentel, who was declared the best orator of the legislature that was just beginning at that time, and captain Joaquim Tomás Lobo de Ávila (FAFES, 1858: 4).

The presence and committed involvement of the military in the Chamber of Deputies made both the military question and the soldiers themselves the central figures in a political game played between 1851 and 1870, in which each faction and each party in confrontation with one another sought to gain an advantageous position, being aware that the military deputies were also important political actors and that the military question was also an important political question. Thus, the various parliamentary factions in dispute with one another, who were clearly pursuing other objectives than the mere interests of the army, sought to make political capital out of the presence of the military men and the debates that were held on the military question. This was the inevitable price to be paid for the access that the military were granted to the parliamentary stage and the opportunity to make their voice heard there, even though those army officers with seats in the Chamber of Deputies sought, whenever possible, to stress their political independence and the specificity of the matters of a military nature that they brought up for debate. This was what the retired brigade general and parliamentarian Belchior José Garcês did, in 1864, when he spoke out against the dismissal of the Viscount of Sá da Bandeira as Minister of War after the publication of the armys new Plan of Organization, a question that he considered to be exclusively military and that therefore only we military men know how to deal with and decide, and these are not questions that should be afforded a great political scope, such as the opposition wishes to give them.6

Being an underlying factor in many debates, the question of the political use that was made of the military was brought openly into debate, in February 1863, through the voice of two deputies of recognized meritLuciano de Castro, belonging to the government majority, and Fontes Pereira de Melo, a captain and engineer, from the opposition. Under discussion at that time was a decision taken by the Joint Committee of the Chamber of Peers and the Chamber of Deputies, relating to the government proposal to create new subjects in the degree course in medicine at the University of Coimbra. Speaking in defense of the military, to which he himself belonged, Fontes Pereira de Melo accused the government majority on the day before the above-mentioned debate took place of treating officers unequally by deliberately postponing a parliamentary bill that were it to be approved would allow for an increase in their retirement pay. Luciano de Castro did not mince his words of reply, What you want is to enter into the good books of the army, with which you are sadly and miserably speculating on a point of mere parliamentary business. Later on, he added that as a result of this postponement, which was not to the liking of various army officers, the opposition does not wish to wait to ascend to the seats of power, instead it went straight outside to stir up the feelings of the officers and to instill in them the idea that the government was opposed to their interests,7 accusing Fontes Pereira de Melo of having set himself up as the spokesman for that discontent for purely political purposes. An accusation that Fontes Pereira de Melo denied, turning it back on the government, which, as far as he could glean from the words of Luciano de Castro, was itself seeking to enter into the armys good books.8 At a time when attempts were being made to bring about national reconciliation, a permanent game of seduction was being played out in the parliament between the political power and the military. Winning or losing the game could make the difference between preserving or not preserving the much-desired political stability in Portugal.

Inside the Chamber of Deputies, the importance of the group of soldiers depended on the size and power of the webs of political influence that they succeeded in weaving around them, by establishing relationships of proximity and interest with other groups and other individual members of the political elite. Such figures understandably included not only the civilians employed at the Ministry of War, or those performing specific duties within the military institution, but also the former comrades-in-arms that the armed conflicts of the first half of the century had temporarily forced into the ranks of the army, and with whom they shared common experiences and greater or lesser degrees of knowledge about the problems faced by the institution. And besides these, there were certainly many others, who were linked to them by ties of kinship, interests or personal relationships that we are now unable to piece together, but which were certainly very much in operation at that time.9

In reality, between 1851 and 1869, the military constituted a strong pressure group10 in parliament, acting as the front line of an army that was passing through a crucial moment in its existence. In this way, the responsibility of the military deputies was made considerably greater. As actors upon one of the most important stages of political power, their performance was closely monitored by the military press, which was already beginning to expand in the second half of the nineteenth century. The Revista Militar, founded in 1848, referred to this situation in its opinion articles, written either by the editors or special correspondents, regularly publishing between 1858 and 1865 a column entitled Extracto das sessões das Cortes sobre assumptos militares (Extracts from the parliamentary sessions about military matters), later replaced by Echo Parlamentar (Parliamentary Echo), which made it possible to accompany the activity of each of the Chambers and its members, session by session, in addition to publishing on a more sporadic basis the list of deputies and civilian employees working for the army who had either been elected as members of parliament or raised to the peerage.11 In this way, the Revista Militar echoed what was happening in parliament, selecting information and giving its military readers a general impression of the chamber and the army officers who had seats there. These formed a group with whom the newspaper did, in fact, enjoy a close and special relationship, due to the fact that some of them were to be numbered either among its founding partners (as was the case with Fontes Pereira de Melo, Augusto Xavier Palmeirim or Joaquim Henriques Fradesso da Silveira) or among its correspondents.

Unlike other professional groups represented in parliament, the military institution had specific formal procedures that facilitated internal communication following a pre-established line of command. Its effectiveness as a hierarchically organized body under what was designed to be a powerfully centralized leadership depended on this. If we add to these official procedures all the other mechanisms that informally made the circulation of information possible, based on ties of solidarity and comradeship that had been forged in specific social environments, such as military schools, barracks or even battlefields, we can understand how in a country where the channels of communication were deficient the military, regardless of where they were positioned on the national territory, were able to quite easily exchange ideas, diagnose problems, propose solutions and join together in defense of common objectives, presenting their demands to their comrades-in-arms who were members of parliament and, above all, to the military deputies, whom they regarded as their direct representatives in relation to the political power. A situation that was seen by (almost) everybody involvedboth the institution itself and the members of parliamentas being perfectly natural. Francisco Maria da Cunha, an army officer elected to parliament in 1865, stressed that a deputy is, first and foremost, a representative of the nation, but that he can also be the representative of a class.12 Yet there were other members of the military who held an opposite opinion. The deputy and second lieutenant Joaquim José Coelho de Carvalho, freshly elected to parliament in 1860, insisted on saying that when I am in this chamber, I am not a soldier, here it is my duties as a representative of the nation that speak more loudly than my duties as a soldier. Outside this chamber, I respect my superiors, obey the orders of all the generals and carry them out without any comment; but, here, in this chamber, I am a representative of the nation and I shall say what I think and feel, even though it may not be to the liking of my superiors.13 Coelho de Carvalho was, at that time, just embarking upon a long parliamentary career that was to end in the Chamber of Peers. Curiously, despite the public stance that he had taken, as a parliamentarian, this deputy always paid special attention to the interests of the military (MARINHO, 2004: 640-641).

In this way, the military deputies were transformed, in parliament, into the spokesmen for the problems of their comrades-in-arms, receiving the individual and collective petitions and representations that, hoping to gain better attention to the issues that they raised, these latter people addressed to them and asked them to present to the Executive Board for discussion during the plenary sessions. A reading of the parliamentary proceedings, especially during the period before the commencement of the days business, shows that this was a role to which the military deputies dedicated themselves with a very special attention and devotion. Throughout the period covered by our study, especially at times when the debate about military questions was more intense, with scores and even hundreds of petitions being presented, there was a constant flood of military representations being presented before the executive board. By way of example, it can be said that, in February 1863, the deputy lieutenant-colonel António de Melo Breyner handed in on just one occasion more than two hundred petitions made by army officers and corporations requesting an increase in pay.14

Besides highlighting the belief in the power of the written word and in the services of the deputies themselves, who either individually or as members of the War Committee, could defend the rights of petitioners, such recourse to the military for the presentation of petitions was a frequent and widespread practice and may even be understood as a demonstration of strength, delivered with an intimidatory force and designed to exert great pressure upon the political power. An act of pressure that, in February 1865, seems to have had a very definite effect. Following the presentation of two bills by the deputy, lieutenant João José Alcântara, designed to increase the pay both of commissioned officers and of the rank and file,15 hundreds of petitions from soldiers were presented to the Chamber of Deputies, expressly requesting the discussion and approval of these bills. Through these, we can gauge the extent of the discontent that was increasingly spreading through the barracks. Such discontent would certainly have influenced the decision of the minister of war, Ferreira de Passos, to present a bill, in that very same month,16 through which he sought to respond to the demands that were making themselves heard so loudly, but which did not get to be discussed in a plenary session. However, the undeniable urgency of the question justified the fact that, on 17 April 1865, the newly appointed minister of war, the Viscount of Sá da Bandeira, should make great haste to renew this proposal, subdividing it into two parts. Placed under pressure by both the forthcoming dissolution of the Chamber of Deputies that some people were predicting and the need to stem the tide of military instability that many people feared, the two Chambers therefore hastened the analysis and debate of these proposals. Approved practically without any discussion, in the Chamber of Deputies, on 13 May 1865,17 or, in other words, on the very eve of its dissolution, they were also discussed and approved by the peers on that very same day in the upper chamber.18 An example of great swiftness that did not always characterize parliamentary proceedings, but which, in this case, was justified by the urgent need to stem the always potentially dangerous discontent of the soldiers scattered around the country.

Seeking to find in parliament the solution to those situations in which they considered themselves to be most prejudiced, the military exercised the right to petition the two Chambers that was enshrined in the Constitutional Charter (Title VIII, article 145, paragraph 28). Thus, if, on the one hand, they could cause their demands and grievances to be heard, on the other hand, they also contributed to a powerful public exposure of the many problems that marked the everyday life of the military institution. A situation that, in most cases throughout the period under study does not seem to have been considered by the army and its leaders as a threat to internal cohesion and discipline so that only in occasional isolated instances did they opt to limit the right of their men to enjoy the full freedom of expression. This would have been what happened, in 1853, when the armys supreme commander, marshal Saldanha sent a circular letter to the barracks prohibiting his officers from exercising their right to petition parliament. At that time, Saldanha accumulated the posts of president of the Council of Ministers, minister of War and commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and sought, in this way, to stifle the growing discontent of the officers who considered themselves to have been cast to one side by the successive events of a political and military nature. A discontent that could endanger the process already underway for reunifying and reconciling the army to which both the government and the parliament were committed and would thrust the country into yet another revolutionary adventure, since the many petitions addressed to the Chamber of Deputies gave a somewhat excessive and undeniably disturbing political exposure to this question. Given the silence of the military deputies who were present in the chamber over a question that was so delicate that it naturally made them feel limited in the scope of their possible positions, both in political and military terms, the situation aroused the indignation of just one single deputy, younger and more fiery,19 and, above all, not hidebound by the environment of the barracks, Cunha Sotto-Maior.20

The petitions presented to the Executive Board of the Chamber of Deputies were distributed to the parliamentary committees considered to be most competent to analyze the questions presented. In most situations, those petitions that were subscribed to by the military were placed in the hands of the deputies belonging to the War Committee, which, in the period between 1853 and 1870, was at the centre of the debate about the military question in the Chamber of Deputies.

2. The War Committee

The importance of parliamentary committees, as factors that conditioned the deputies capacity for intervention and decision-making, has already been highlighted (MANIQUE, 1992: 115; MAIA, 2002: 145). Seen as the backbone of the parliamentary structure, and being the first level for the assessment of the bills proposed by the government and those proposed by private members of parliament (whether deputies or peers), which were then submitted to the consideration of each of the chambers, the committees wielded enormous power. Besides formulating the opinions about which the parliamentarians would take a position after their discussion in an assembly (in most cases, the opinion enunciated in the original document would prevail), the committees marked the rhythm of parliamentary business, intensifying it or slowing it down in accordance with their own capacity for work or their political interest in causing a certain matter to be allowed to advance further or to be silenced. The possibility of the committees setting themselves up as an effective counterbalance to the power of the government, sifting the matters to be discussed through their tightly-knit mesh, analyzing, frequently rather summarily, those that they found convenient, and holding back, even in the face of the aggressive demands made by the other deputies, sometimes on a definitive basis, those subjects that seemed to them to be inopportune, all of this justified the constant reference to the bills and legislative proposals that, once they had been channeled there, remained there forever.

In this way, it can be understood that a place on a standing committee, especially on one of those that were considered to be amongst the most importantincluding the Treasury Committee, the Petitions Committee, the Foreign Affairs Committee and, for reasons that will be outlined later on, the War Committeerepresented the great ambition of most of the deputies who sought to embark on a political career, even though this inevitably meant a greater workload and an increase in the number of hours that were to be dedicated to parliamentary activity. The words of Ricardo Guimarães, written in 1863, about the procedure to be followed in electing the committees of the Chamber of Deputies, in each legislative session, are fairly elucidatory about this matter: For a fortnight, the deputies have been coming to the parliament to place lists into two ballot boxes. And despite the wearisome nature of this task, which reduces members of parliament almost to the level of lottery ticket salesmen, by dint of the lists that are thrust into their hands, you frequently find that the session is attended by countless deputies. For it is the ballot boxes of the committees that are the ballot boxes that determine the fate of many of those who most passionately fight for the votes of their colleagues (GUIMARÃES, 1863: 126).

Although it was recognized that the election of the committees could depend upon friendships and interests,21 in practice it did, in fact, depend on matching the educational profile and/or professional experience of the deputy to the committee to which he should belong, especially in the case of those committees whose specialty required a more specific knowledge and a higher level of technical skills, such as the Diplomatic Committee (MAIA, 2002: 150), the War Committee, or even the Ecclesiastical or Legislative Committee. Matching the profiles in this way had its positive and negative aspects. In fact, while on the one hand it may have allowed for a better use of the deputies skills and technical capacities, it did, on the other hand, help to make the committee impervious to other points of view, haughtily considering itself to be the absolute holder of unquestionable truths (MAIA, 2002: 151). Even if they sought to avoid such a situation, the work of the committees was nonetheless suspected of bias and corporatism. In 1863, referring to several committees in particular, Sá Nogueira showed himself to be particularly caustic in his criticism of the War Committee, It is a question of electing the war committee, everyone who is elected is a soldier; a bill is put forward in which the interests of someone are offended, and it is already known that the opinion is against them.22.

The fact that the professional background and/or training of the deputies coincided with the specific area of analysis of the committee that they belonged to made it possible for some socio-professional groups that enjoyed representation in parliament to strengthen their power through the exclusive use of a structure that, as we saw earlier, had a great capacity for influencing the decisions of the Chamber of Deputies and for determining the pace and rhythm at which this body worked. In the particular case of the War Committees that are of interest to us here, the specificity and the high level of technical skills required by the analysis of multiple military questions justified the fact that, over the years, between 185323 and 1870, those who were chosen to serve as members were almost exclusively army officers in active service or in a situation of retirement, joined on occasions by civilian officials from the Ministry of War and/or magistrates linked to the Supreme Council of Military Justice24 [see APPENDIX II]. Regardless of whether they were elected by all the deputies25 or by the sections,26 or even, in exceptional cases, appointed by the Executive Board, as happened in the legislative session that began on 4 November 1860, or else re-appointed,27 the members chosen were almost invariably army officers who already had seats in parliament, some of them being chosen more than once. António de Melo Breyner, Augusto Xavier Palmeirim, Belchior José Garcês, Joaquim Bento Pereira, José Guedes de Carvalho e Meneses, Luís da Câmara Leme and Plácido António da Cunha e Abreu are some of the soldiers whose names appeared most frequently as members of the War Committee. Amongst the civilians, attention is drawn to the names of the magistrates António José de Barros e Sá and Miguel Osório Cabral and the official from the War Ministry, Carlos Cirilo Machado.

The War Committee played a major role in parliamentary dynamics between 1853 and 1870, being the main protagonist in the incessant parliamentary debates on the military question, seeking insofar as possible to ensure that corporative interests were compatible with political interests. They did not always succeed in doing so.

In 1855, the War Committee of the Chamber of Deputies invoked the notion of just offence in order not to give an opinion about the parliamentary bill relating to reparations for pensions that were considered unfair and the passing over of various army officers who were due for promotion. A proposal that was eminently political in its intent, since it either directly or indirectly involved soldiers related with revolutionary moments, as well as going against an opinion that had been issued in the previous year about the same subject, and by the same Committee. Consequently, in its attempts to avoid having to take a clear stance on the matter, the War Committee proposed that, under the scope of its prerogatives, the Chamber should set up and empower a special committee to do so.28 This proposal ended up not being approved, despite the fact that, faced with the criticisms of the deputies, Palmeirim resorted to a second argumentthe degree of kinship existing between some members of the Committee and the officers that were affected by the aforesaid parliamentary bill and who consequently viewed it with suspicion.29 This argument, which does not, however, seem to have affected the adoption of more positive stances in many other areas, consequently enjoyed very little support amongst the other deputies. Silvestre Ribeiro spoke highly critically of the attitude of the War Committee, claiming that it was the committees obligation to take an unequivocal stance upon the matter,30 and suggesting what he considered to be the real reason for its not doing sothe Committees lack of political courage to go against a government proposal and publicly express its disagreement.31 Caught between the interests of the soldiers and the institution to which they belonged (and which many of them considered that they represented in parliament) and their party loyalty, the members of the War Committee chose, in this case, to sit by and do nothing, leaving the responsibility of decision-making to others. This was the dilemma that was frequently placed before the soldiers who had seats in parliament, especially those whose names were recorded as belonging to the government majority. As was said earlier, their passage through parliament could mean their advancement in the military hierarchy, which at that time was based on rules that were not entirely transparent, while their appointment to attractive positions in the public administration and their consequent adoption of politically incorrect positions could mean that they would be kept far removed from all of this.

In this way, it can be understood that, without exposing itself too openly to the accusations of the Chamber, the War Committee should resort, on other occasions and in relation to other equally sensitive matters, to temporarily or permanently holding back legislative proposals or parliamentary bills that were politically inconvenient. A strategy that did not go unnoticed by the skilled intuition of the deputies. This was what happened in 1857, with the opinion about officers who were passed over for promotion after the political events of 1846, which led the deputy Santana e Vasconcelos to say that, The illustrious war committee that has been so solicitous about presenting its opinions on matters requiring such careful thought seems to me, in this matter, to have been, I wont say less zealous, because I do not wish in any way to imply any censure of it, but a little more forgetful.32

Despite the many criticisms that were leveled against it, and in comparison with the other committees, the War Committee demonstrated a remarkable capacity of response in the Chamber of Deputies to the workload that was continuously thrust upon it. Distinguishing itself through the sheer amount of opinions that were presented for discussion (as proof of this, the deputy Lieutenant-colonel Melo Breyner reckoned that, in 1857, one third of the business presented for discussion to the Chamber of Deputies came from the War Committee),33 the work that was performed by this committee underlined the commitment that, in most cases, its members displayed in their defense of the positions that it had adopted and through which they sought to galvanize and unite all the soldiers with seats in parliament, bringing up for discussion both legislative proposals and parliamentary bills that were of interest for the army and the military in general.

Although they formed part of a system that had specific procedures for its operation and functioning, the War Committees reproduced the military reality, being internally structured according to the hierarchical principle on which this was founded. Consequently, in most situations, the choice of the Committees president, a position of highly symbolic power, invariably fell upon the members of the highest military ranks. By way of example, we can mention that, at the legislative sessions of 1853 and 1854, the War Committee was presided over by brigadier José de Pina Freire da Fonseca, at the session that began on 4 November 1858, by lieutenant-colonel António de Melo Breyner, at the legislative sessions beginning on 2 January 1856, 4 November 1862 and 2 January 1864, by brevet brigadier Xavier Palmeirim, at the session that began on 15 April 1868, by general Manuel José Júlio Guerra, and, at the session beginning on 26 April 1869, by lieutenant-colonel Fontes Pereira de Melo. In turn, the lieutenant-colonel and later colonel Belchior José Garcês presided over the War Committee on four occasions, at the legislative sessions of 1860-61, 1867 and, in 1870, at the sessions that began on 2 January and 31 March respectively.

The choice of the secretary and the rapporteur, whether these figures were established at the time when the Committee was formed or whether they were appointed specifically for each matter under debate, was certainly in keeping with the individual predispositions of each of the members, since the first was required to be dedicated and constantly present at meetings and the second was required to have knowledge about the matters in hand and to display a fluent discourse. This explains why, as secretary of the War Committee of the Chamber of Deputies, a figure whose official duties were essentially bureaucratic and certainly called for daily monitoring of the business in hand, we find low-ranking officers such as the deputies, lieutenant João José de Alcântara (at the session from 30 July 1865 to 26 December 1865), captain António José Pereira de Antas Guerreiro (at the session that began on 15 April 1868), or captain D. Luís da Câmara Leme, who filled this post on more than one occasion. Exceptionally, on certain specific occasions, this position was given to a civilian, Cirilo Machado, an official from the War Ministry, at the legislative sessions of 1853, 1854 1855 and 1856, and to the recently resigned army officer, Francisco de Azeredo Teixeira de Aguilar, the Count of Samodães, in 1857. Reflecting the political games underlying the setting up of the parliamentary committees and the internal distribution of the different posts for their members, we are faced, in the first case, with a regenerator who enjoyed the confidence of Saldanha (SARDICA, 2005: 672), who, while the latter was in power, was systematically chosen as the secretary, being replaced when he left by one of his self-confessed political adversaries, who had been dismissed from the army in 1851 for having distanced himself from the April uprising (MARINHO, 2004b: 74).

The closed and heavily corporatist nature of the War Committee of the Chamber of Deputies, which was clearly illustrated by its composition and membership, turned it into the preferred target for the criticism of some deputies, who were aware of the great political importance of its stances on certain issues and its defense of the interests of the military and the army. Overburdened with work, but also endowed with a capacity of response that was clearly greater than that of the other committees, as a result of the effective distribution amongst its various members of the different subject-matters that it had to deal with34, instead of submitting them to the consideration of the group as a whole, the War Committee exposed itself more to the eyes of everyone in parliament, frequently being accused of partiality and favoritism, especially when it was called upon to express its opinion about matters related with the specific situation of a certain soldier. This was what happened, for example, in July 1852, when the Count of Samodães, as a member of the War Committee, informed the Chamber that this has been accused outside, by the newspapers, of being unfair, biased, and not acting in accordance with the Law. Some of those that have written in these newspapers say that there is, in this committee, patronage, that there is immorality, and, in short, it has been called all the names under the sun,35 accusing those who had seen their petitions rejected of genuinely leading a campaign against the War Committee.

However, the criticism frequently came from within the parliament itself, originating amongst the civilian members, who were occasionally joined by the odd soldier who was more discontent with the slow solution of the problems facing the army, due to the way in which the Chamber functioned, which obliged the War Committee to put forward a number of minor proposals,36 relating to personal questions, and to constantly postpone dealing with the more important and more complex matters. Amongst these soldiers, attention is drawn to the infantry lieutenant Fernando Luís Mousinho de Albuquerque. Having been a deputy in the last legislatures of the 1850s, this soldier did not shrink from directing some fairly poignant criticisms at the War Committee, whose workings he knew well from the fact that he himself had been a member of the committee on various occasions, namely as its rapporteur from June 1858 to November 1859. Considering that the Committee was only meant to deal with business relating to purely war-related technical matters, and not with the personal requests of the military, Mousinho threatened in 1859 that he would not take up his seat in parliament again unless the necessary measures were taken to avoid that situation, because, The war committee examines and takes note of the past life of each of the members of the military, because all their claims and complaints are based upon this. The circumstance of our being soldiers in an army in which we have been fighting with one another, makes us suspect in conducting such an examination. If the complainant is one of those who served in the opposite camp to our own, one can see how embarrassing and terrible is the position of a member of the war committee finding himself obliged to sign an opinion against a comrade who might then attribute to spite what is no more than the fulfillment of his duty. In this case, the position is even worse when we have to express an opinion against a friend.37

In reality, the division and confrontation that had internally marked the army in the first half of the nineteenth century justified many petitions being made by soldiers who considered themselves to have been unfairly treated and requested either promotion or re-admittance to the army. The desired reconciliation meant that these corrections were considered to be a priority by the War Committees, thereby delaying the expression of opinions on other important matters that would make it possible to restructure the army along entirely new lines. However, without such reconciliation, it would be hard to lay the new foundations for the army that its members wished to have. Classified, therefore, as highly political measures,38 involving heavy financial costs, they called for a coming together of wills and required the government majority to be in harmony and agreement with the government. The analysis of these questions therefore became more complex, placing even greater restrictions on the decision-making of the War Committee and the military members of parliament. Under pressure from both sides, both from their comrades-in-arms, with whom they shared problems and ambitions, and from the political factions to which they belonged, even though they were still free from the constraints of party discipline, the members of the War Committee were certainly led, in some cases, to put to one side the corporatist spirit and the interest of the military institution, and to adopt politically more correct positions.

In January 1862, seeking to escape from this controversy that enveloped it in a climate of suspicion, the War Committee of the Chamber of Deputies, whose secretary at that time was D. Luís de Câmara Leme, decided not to proceed with any matters relating to private individuals until such time as the more important general questions had been analyzed,39 which had been dragging on from legislature to legislature. In fact, at the military level, in 1851, everything still remained to be done, ranging from the definition of the new principles regulating recruitment to the reorganization of the institution itself. With the intervention of the soldiers present in the Chamber of Deputies, particularly those who were members of the War Committee, something was finally to be done in 1870.

3. The activity of the War Committee and the military deputies.

Throughout the period that is being analyzed in this study, although their discourse remained constant whenever matters of a military nature were being discussed, the military deputies showed themselves to be particularly active and committed in relation to the question of recruitment and the costs that the upkeep of the army represented for the countrys finances.

Going beyond the boundaries of a merely military question, recruitment took on the quality of an ideological, political, economic and social question of prime importance, which, in the period from 1851 to 1870, was given special emphasis by the Regeneration. Elevated to the status of a national question and, as such, afforded a greater airing in parliamentary debates, recruitment was a constant political issue of the time, as it placed all different kinds of points of view and interests in direct confrontation with one another. A debate that was monopolized by the Chamber of Deputies, which was constitutionally responsible for matters relating to taxation (Carta Constitucional, Tít. IV, Cap. II, Art. 35º, § 1º), recruitment (Carta Constitucional, Tít. IV, Cap. II, Art. 35º, § 2º) and the annual fixing of the ordinary and extraordinary land and sea forces, at the proposal of the government (Carta Constitucional, Tít. IV, Cap. I, Art. 10º).

Such a situation provided double justification for the exclusive right that parliament claimed for dealing with the question of recruitment, which during most of the nineteenth century, was frequently referred to as the greatest of all taxes, the blood tax.40 Certainly a very weighty expression, but no less weighty was the image that the question had amongst the general population, given the discordant voices of such military deputies as lieutenant-colonel António de Melo Breyner when he stated that military service is a duty that all are obliged to fulfill, and it is extremely hard to hear it said that recruitment is a blood tax: it is not considered to be a tax. It is meant to be a duty; if it is a duty, then it cannot be called a tax, and so much so that we do not levy at so many per cent the drops of blood that the soldiers shed on behalf of their country.41 In practice, however, thirty years after the liberal revolution, the population continued to regard military service more as a burden of taxation than as a duty of citizenship.

The need for a new recruitment law was therefore generally agreed upon by both the military and civilian men who sat in parliament, in the first few years of the 1850s. The existing legislation was deficient and inadequate for the principles set out in the Constitutional Charter, since it [did] not satisfy the needs of the country, nor even of the army itself, which has the mission in wartime of defending both the independence and the honor of the nation; and, in peacetime, of conserving order, safety and public tranquility,42 bringing to the ranks vagrants and men of irregular behavior devoid of patriotic feelings and any sense of civic duty and virtue. The French model of recruitment adopted in 1832, based on conscription and a lengthy period of service, showed itself to be the best way of forcing those members of society that until then had kept themselves at a goodly distance from the army to end up joining it, without, however, requiring large annual forces, which would reinforce their extreme distaste for military life and would require the government that decided upon these numbers to pick up the tab and pay the respective political bill.

Questioning the committees that had been put in charge of this matter, requesting information from the War Ministry and the Ministry of the Kingdom (Ministério do Reino), appealing to the ministers and presenting parliamentary bills,43 but without demanding the sort of exclusivity that they claimed for other matters, the military spoke assiduously in the Chamber of Deputies upon the subject of recruitment. They did so not only because they recognized that recruitment lay at the very foundations of the army to which they belonged, but also in their capacity as representatives of the nation, steadfastly rejecting the accusation that this was a question of personal interests.44

In 1855, the first great debate on recruitment took place, which the military did not seek to monopolize, only speaking occasionally whenever they saw fit. After more than thirty sessions, a law was approved that, although many deputies considered it to be the best recruitment law that the country had ever had, nonetheless contained certain flaws that made its application difficult and introduced the need for the subsequent introduction of a number of specific alterations. In May 1859, the Public Administration and War Committees expressed their joint opinion on a proposal made by the minister Fontes Pereira de Melo, who, amongst other things, proposed introducing the possibility of purchasing remission from the compulsory nature of military service, while also maintaining the practice of substitution, which was already enshrined in the law of 1855. According to that law, substitution allowed the young man whose number had determined his entry into the ranks of the army to recruit another man to replace him, in exchange for the payment of an amount of money that was to be agreed upon between them. In view of the high level of criminality that was to be found amongst the replacements45, and recognizing the need to look for other ways of supplying the army when the young recruits were themselves unwilling to perform military service, the above-mentioned Committees accepted the proposal of allowing recruits to purchase remission from service put forward by the government, and submitted it to parliament for its consideration. The proposal was approved without any significant opposition.

However, the question of purchasing remission from military service, which was enshrined in the Law of 4 July 1859, was to fuel a controversy that dragged on for some years, clearly dividing the deputies who sat in parliament. Heavily criticizing the principles underlying the procedure of purchasing remission from military service, the military, and in particular those who were members of the War Committee, speaking in defense of what they considered to be the armys interests, ended up actively defending its abolition.

The first great parliamentary battle over this question took place in 1861, when the War Committee consisting of the soldiers, the Baron of Rio Zêzere, Plácido António da Cunha e Abreu, José Guedes de Carvalho e Meneses, Carlos Brandão de Castro Ferreri, Fernando de Magalhães Vilas Boas and the Count of Vale dos Reis, in addition to Belchior José Garcês himself, took a stance in opposition to the position adopted by the Minister of War, the Viscount of Sá da Bandeira, in the debate on the proposal that he himself had presented on 1 March. Pointing out the harmful consequences for the army of accepting the legal possibility of being able to purchase remission from military service (which they considered to be responsible, in 1861, for the 1705 vacancies of which the State was only able to fill 455 through the contracting of replacements), the Committee completely altered the contents of the ministerial proposal, establishing entirely opposite principles in the bill that they presented to the Chamber of Deputies. Whilst, in stressing the negative effects of such substitutions, the ministerial proposal set the price of remission at 150 thousand réis and called for the setting up of a pay office to manage that fund, the War Committee submitted to parliament, for its consideration, a bill whose very first article would revoke Article 7 of the Law of 4 July 1859, which, as we saw earlier, regulated remissions from military service and was in favor of the mechanism of substitutions.46 A fairly unusual situation that gave rise to great controversy among the deputies and did not meet with the approval of two military deputies, second lieutenant Joaquim Coelho de Carvalho and brigadier Augusto Xavier Palmeirim, whose parliamentary activity was marked by the defense of the military and the army (MARINHO, 2004: 640-641; SARDICA, 2006: 171). They both put their names to the proposal to postpone discussion of the article that would put an end to the purchase of remissions from military service, while leaving the other articles up for discussion. In view of the unusual nature of this situation, this was certainly the most convenient path to follow in political terms, so that the proposal was passed by the Chamber of Deputies.47 With the defeat of the War Committee, the government succeeded in gaining approval, on that same night of 3 August 1861, for the setting up of a fund into which would be channeled the money originating from the cash paid for remissions from military service, as stated in one of the articles of the parliamentary bill presented by the Minister of War, Sá da Bandeira.

In reality, putting an end to the purchase of remissions from military service, as was the wish of the members of the armed forces serving on the War Committee, would represent a harsh blow for the political aspirations of some deputies who used conscription as an important electoral weapon, although (in a way that was more or less clear) they recognized the harmful effects of maintaining it, not only for the army, but also for society itself. Keeping the system of substitutions and the possibility of purchasing remission from military service was justified in the light of their wish to please the local political bosses, continuing to allow them legal loopholes for ensuring that their children and protégés could be spared the need to do military service, in exchange for much-needed votes. Furthermore, the existence of legal mechanisms for avoiding military service allowed the wealthier classes the chance to remain exempt from such compliance, in a society that was still relatively unprepared to accept military service as a duty of citizenship. Revoking the possibility of purchasing remission from military service and maintaining only the system of substitution would mean accepting a political price that no faction, regardless of whether it belonged to the government majority or the opposition, would be in a position to pay at that time.

The postponement of the discussion about the abolition of the possibility of purchasing remission from military service, a measure that was presented in 1861, represented a serious setback for the War Committee. Regrets were expressed in the Chamber of Deputies, not only by the military deputies, but also by the various civilian deputies, including José Estêvão. Referring to the unpopularity of a measure that enabled people to purchase remission from military service, due to the fact that it was not known what use the State made of such money and the fear that it might be channeled into other purposes, Estêvão declared himself to be radically opposed to any form of substitution in the performance of military service, concluding that we will not have an army if people lack the courage to decree this principle and to make sure that it is observed blindly, namely that all citizens, all individuals, all young men, whatever their place in the hierarchy, upon whom the luck of the draw has fallen, shall serve, no matter whether they have millions or belong to the highest echelons of the state. These men, and not others in their place.48 Most of the military deputies were not prepared to go so far, accepting the mechanism of substitutions as a lesser evil, which, despite everything, made it possible to replenish the ranks.

However, the setback suffered by the military members of the Chamber of Deputies War Committee, in 1861, did not cause them to abandon their proposals, transforming the question of remission from military service into a battle horse that was agreed upon in each opinion that they presented about the bills proposed by the war ministers for the annual establishment of the size of the land forces and their respective distribution. This was what happened in 1862, when the War Committee reminded parliament of the need to revoke article 7 of the Charter of 4 July 1859, relating to remission,49 obliging the Chamber of Deputies to once again reflect upon this question. The military members of the War Committee considered remission to be a mechanism of recruitment that was unfavorable to the army, transforming the State into a banker for recruits,50 with money, but without soldiers when we need soldiers and not money. However, in seeking to escape from the pressure, the Chamber did not allow itself to be deceived by the strategy of the Committees military members, who wished to force it to take a decision on this matter. Although many of the deputies referred negatively to remission as a privilege of the rich,51 the Chamber of Deputies maintained that its abolition could only be analyzed within the broader context of a reform of the law of recruitment. A reform about which there were already several legislative proposals, but which, when they were handed to the Public Administration Committee for analysis, came up against an evident lack of the political will needed to bring them up for discussion in parliament.52 According to the Chamber of Deputies, it was because of a question of principle that, despite its efforts, the War Committee was unable to get around the fact that a ruling of a permanent nature, such as the abolition of the purchase of remission from military service, should not be included in a temporary law seeking only to establish the size of the armed forces for the current year.

The following year, in 1863, the Chamber of Deputies War Committee, composed of the soldiers Augusto Xavier Palmeirim, Plácido António da Cunha e Abreu, Fernando de Magalhães Vilas Boas, José Guedes de Carvalho e Meneses, D. Luís da Câmara Leme, João Nepomuceno de Macedo, João Crisóstomo de Abreu e Sousa and António de Melo Breyner, took advantage of the legislative proposal made by Sá da Bandeira about establishing the size of the armed forces to once again promote a discussion on the question of putting an end to the possibility of purchasing remission from military service. In the preamble to his proposed bill, Sá da Bandeira insisted on the harmful effects for the army of the possibility of paying cash for the remission of military service, with article 3 providing for its abolition.53After being approved in its general sense,54 the discussion of the particular details of the law spread over three sessions and once again highlighted the fact that most of the military deputies were in agreement about this question.55

Setting a heated discussion in motion, Pereira de Carvalho e Abreu, a deputy who had no links with military circles, defended the system of remissions and substitutions, pointing out that for the young man who does not wish to serve, if the law does not permit substitution or voluntary remission, enforced remission is marvelously converted into optional remission,56 thereby increasing the number of deserters. In turn, and defending its abolition, the deputy from the War Committee, major Plácido de Abreu, referred to the increasing shortage of soldiers, the poverty of the farmers from the Minho, who, because of the payment of their remissions, found themselves caught in the clutches of usurers, moneylenders and rich men,57 also stating that If the army does not imbibe fresh Portuguese blood on a constant and yearly basis, then the army may be an element of tyranny, but never an element of freedom,58 maintaining in its ranks men whose time of service has already come to an end, but who could not be discharged, at the risk of the army ceasing to exist because of a lack of soldiers. However, more than just the principle of remission, what seems to have been at stake, as the same deputy explained, was the fact that the remission process was performed through the State, That is to say that the State is the banker or broker in this transaction. The committee leaves remission to the individual who is interested in the business; and he is left responsible for adapting it, arranging it and promoting it, and for doing it in the way that he considers most convenient,59 thus making it possible for more accessible prices to be charged.

In a repetition of what had already happened in 1861, the proposal presented by Cirilo Machado for a postponement in relation to articles 2 and 3, introduced by the War Committee into the governments legislative proposal regarding the establishment of the size of the army, was put to the vote. In the session of 11 June 1863, although most of the military deputies cast their nominal votes in support of the War Committee, some of them once again distanced themselves from the committee. Amongst the 46 votes that rejected the proposal for a postponement, as against the 40 votes cast in its favor, were those of the army officers, Carlos Brandão de Castro Ferreri, Augusto Xavier Palmeirim, the Baron of Rio Zêzere, Belchior José Garcês, José Rodrigues Coelho do Amaral, D. Luís de Câmara Leme and Plácido António da Cunha e Abreu. However, in the opposite camp, defending the postponement of the discussion were four members of the military. The three members of the War Committee who signed their names together with an explanation for the way in which they had voted, lieutenant António de Melo Breyner and the captains João Crisóstomo de Abreu e Sousa and Fontes Pereira de Melo,60 were also joined by António Júlio de Castro Pinto de Magalhães. Two of them justified their position. João Crisóstomo de Abreu e Sousa referred to the need to avoid undermining the authority of the parliament by changing the recruitment laws every year61. In turn, at the next session, Fontes Pereira de Melo, without contradicting the position adopted by most of the military in relation to the matter in question, traced the history of the systems of substitution and remission and mentioned that this latter procedure had in its favor the fact that the young recruits handed the money directly to the State without having to resort to the scandalous usury that the system of substitutions allowed for62, thus avoiding their becoming caught up in the cogs of a system operated by private individuals who, capitalizing on the shortage of available substitutes, were able to greatly inflate the prices to be paid. And to prevent the War Committee from continuing to use that same stratagem for bringing this subject up for debate, he proposed to the Chamber of Deputies that, before all else, it should determine that it was not convenient, in the annual law for the establishment of the armys size, to decide upon other matters that had to do with the basic law of recruitment. His proposal was not accepted by the Chamber of Deputies and the parliamentary bill was approved: besides establishing the contingent of recruits for that year, it also maintained the system of substitutions, but abolished the possibility of purchasing remissions from military service. Everything seemed to be in place to ensure that, after their failed attempts in the previous two years, the military members of the War Committee would finally succeed in bringing an end to the possibility of purchasing remission from military service.

However, before a definitive victory could be declared, the approval was still required of the Chamber of Peers, where the bill was also to enjoy the favorable opinion of the respective War Committee, composed of the armys highest-ranking officers, field marshal Viscount of Nossa Senhora da Luz, brigadiers José Maria Baldy and D. António José de Melo e Saldanha, general Count of Melo, as well as the civilian Joaquim Filipe de Soure, the latter including a statement explaining the way in which he had voted as he considered the system of substitution to be more harmful to the army than that of remission63. There was therefore a general consensus in the positions adopted by the members of the military serving on the War Committees of the two Chambers. An agreement that did not, however, extend to its other members. Faced with the silence of the military peers belonging to the respective War Committee, which could equally well indicate either compliance or the inability to fight, and the allegation that it went beyond the aim of the already-mentioned bill, which was to establish the military contingent for the current year, the Chamber of Peers approved the bill by eliminating the articles relating to substitutions and remissions64. Despite its displeasure with the position adopted by the peers, the Chamber of Deputies found itself obliged to accept the changes that were made to the bill. It was already June, and the legislative session was drawing to a close, so that there was no time for a battle to be fought between the two chambers. However, the member of the War Committee, Plácido de Abreu, insisted on promising that this same Committee would not abandon its defense of the ideas that it had upheld in the discussion of the earlier bill, already mentioned above .65

In keeping with what had been promised, the struggle of the military members of the War Committee for the abolition of the possibility of purchasing remission from military service continued until 1865. However, thereafter, the discussions about the proposals for the distribution of the contingents involved less conflict and the question of remissions and substitutions was only occasionally brought up in the speeches of individual members of parliament, although there was not now sufficient force to fuel a more heated debate in the Chamber of Deputies. The greater projection that was given in parliamentary debates to other matters of a military nature, such as the reorganization of the army, military training and rearmament, all considered from the broader perspective of National Defense (a subject the political and military situation in Europe had turned into a matter of great urgency), began to monopolize the attentions of the military in the Chamber of Deputies, and above all the attention of those who belonged to the War Committee, relegating the question of remissions66 to a secondary position.

A recurrent theme of discussion during the chronological period covered by this study was that of the need to maintain a well organized and well trained army, as well as the costs that this involved, a subject that justified the intervention of the military deputies in the plenary sessions of parliament. A reading of the parliamentary proceedings shows that this discussion was not only an underlying theme of the debates taking place about military questions and matters of National Defense, such as the building of fortifications, the purchase of arms or the reorganization of the army, which heavily marked the agenda of the Chamber of Deputies throughout the 1860s, but also of the debates about the State budget and, in particular, the budget of the War Ministry. As stated in 1854 by Cirilo Machado, an official at this same ministry and a member of the War Committee, An army, without enjoying the conditions that it should have, without being well armed and well equipped, in which the soldiers are poorly fed and do not do exercises, filling the hospitals in their sickly and rachitic state, is not an army, is not fit for any purpose, and is very expensive, no matter how small the amount that is spent on its upkeep.67 With the return of the military to the barracks and the process of reconciliation that was already underway, there was a need to make choices and decide upon the paths that were to be followed.

The military deputies could choose from two possible pathswhether to have an army of the militia type or to have one of the permanent typewhereby Either all citizens are to be entrusted with the nations military defense, sustaining public order and national independence, or they will have to contribute with their own funds so that only a part of them are entrusted with this mission. It must be known, and it must be decided, whether they wish or consider it better for there to be a force entrusted with the nations defense, honor and dignity, or to have all citizens armed with a rifle and standing at the door of their houses to defend their safety and their independence.68 Faced with such a choice, the military deputies had no doubt about which path they should follow. The same could not be said of some civilian deputies. The material and human costs that were involved in maintaining an army of the permanent type justified the jurist Manuel Vaz Preto Geraldes noting, in 1862, that it is a problem that has not yet been solved, whether or not our small kingdom should or should not have an army.69

Words such as these, which the press caused to echo all around the country, became particularly powerful whenever the budgets of the War Ministry were being debated, with a very clear dividing line being drawn in parliament between its military members and some civilian deputies who were critical of the army and, in particular, of the expenses that were involved in its upkeep.