Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Psicologia

versão impressa ISSN 0874-2049

Psicologia vol.11 no.1 Lisboa jan. 1996

https://doi.org/10.17575/rpsicol.v11i1.591

The role of group status and history of the conflict on intergroup discrimination strategies

Maria Luísa Lima*; Maria Benedicta Monteiro**; Jorge Vala***

*-**ISCTE, Lisboa

***ICS, Lisboa

ABSTRACT

According to Tajfel Social Identity and Intergroup Relations Theory, perception of higher status in intergroup conflict is claimed to elicited both stronger Statements of ingroup identification and stronger ingroup favouritism than perceptions of lower status. It was hipothesized that the degree to which both higher and lower status conflicting groups assert ingroup identity and display ingroup favouritism also depends on the history of the conflict. This variable reflects the perceived ratio of gains and losses in the past, as well as the present expectations of positive or negative change of the status relations. A linear history of conflict (without a significant change on groups’ status position) is expected to induce weaker comparisons between groups as well as lower expectations of change, thus eliciting lower ingroup favouritism and ingroup identification assertions in both groups. Non-linear history of the conflict (with significant reversal of group’s status position in the mid-run) is expected, on the contrary, to enhance comparability between groups and expectation of change, thus eliciting stronger group categorizations, stronger assertations of group identification and higher ingroup favouritism. An experimental study was design to study these predictions. The experiment was a two factor design experiment (high vs. low status; linear vs. non-linear history of the conflict) where college students participated in a simulated conflict between two induced groups. Perceived legitimacy and stability of the status relations were controlled and group identification and intergroup differentation strategies were observed. Predictions about the importance of the conflict to moderate ingroup identification assertations and ingroup bias were confirmed.

RESUMO

De acordo com a Teoria da Identidade Social e das Relações Intergrupais de Tajfel, a percepção de um estatuto superior conduz a uma maior identificação com o grupo próprio e a um maior favoritismo para com o grupo próprio do que a percepção de um estatuto inferior. Foi hipotetizado que o grau em que grupos em conflito, quer sejam de estatuto inferior ou superior, afirmam a sua identidade grupal e exibem favoritismo para com o grupo próprio depende também da história do conflito. Esta variável reflecte quer a razão percebida entre os ganhos e as perdas passados, quer as expectativas de mudanças positivas ou negativas nas relações ao nível de estatuto. Uma história do conflito linear (sem mudanças significativas nas posições de estatuto dos grupos) induzirá quer comparações mais fracas entre os grupos, quer menores expectativas de mudança, conduzindo assim, em ambos os grupos, a um menor favoritismo pelo grupo próprio e uma mais fraca identificação com o grupo. Uma história de conflito não-linear (com inversões significativas das posições de estatuto dos grupos) induzirá, ao contrário, maior comparabilidade entre os grupos e mais fortes expectativas de mudança, dando origem assim a mais fortes categorizações grupais, mais fortes afirmações de identificação com o grupo próprio e maior favoritismo para com o grupo próprio. Um estudo experimental foi concebido para estudar estas previsões. O estudo teve um desenho factorial 2x2 (estatuto superior vs. inferior; história do conflito linear vs. não-linear) em que estudantes universitários participaram num conflito simulado entre dois grupos criados experimentalmente. A legitimidade percebida e a estabilidade das relações de estatuto foram controladas e a identificação grupal e as estratégias de diferenciação intergrupal foram observadas. Foram confirmadas as previsões acerca da importância do conflito na moderação das afirmações de identificação com o grupo próprio e nos enviesamentos a favor do grupo próprio.

Introduction.

Some years ago, we began a research project which aimed at understanding social conflicts within organisations. We wanted to apply the framework of Social Identity and Intergroup Relations Theory (Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Tajfel, 1982) to those kinds of realistic conflicts between two professional groups which take place within the same organisation. We think that this theoretical framework can help us to understand and predict the organisational responses of the groups in conflict.

Social Identity and Intergroup Relations Theory has widely postulated the importance of the group status variable on the intergroup favouritism and discrimination phenomena, explained as a way to protect positive group distinctiveness and, therefore, enhance a positive social identity of group members. In the kind of organisational conflicts we study, group status is also an important variable, and it can easily be operacionalized by the mean wages of the professional groups in conflict.

But, so far, the intensity and the orientation of ingroup favouritism and intergroup discrimination do not appear in empirical findings in a consistent way

According to substantial empirical research, dominant groups present higher patterns of outgroup discrimination than dominated ones, the outgroup discrimination becoming stronger whenever group status is unstable, and group members perceive the status quo as legitimate. Conversely, dominated groups would be characterised by lower patterns of ingroup favouritism, namely where group boundaries are perceived as salient and sharp, intergroup asymmetry is perceived as legitimate and stable. This behavioural pattern of inferior status groups can be, in the light of Tajfefs theoretical framework, the source of collective strategies oriented towards positive social identity (Commins & Lockwood, 1979; Caddick, 1982; Van Knippenberg and van Oers, 1984; Sachdev & Bourhis, 1987; Tajfel, 1975; Turner, 1981; Turner and Brown, 1978; Lambert et al., 1960; Brown, 1978).

In some other researches, nevertheless, a reversed pattern of low status ingroup favouritism has been found.

Some researchers have already shown, both in experimental and in field settings, that low status or socially dominated groups can present higher outgroup discrimination patterns than high status/dominant groups who, in turn, mainly displayed a fairness pattern towards the other group members (Gerard and Hoyt, 1974, Turner, 1978, Turner and Brown, 1978, Turner, 1981, Brantwaite and jones, 1975, Brantwaite et al. 1979, Hewstone et al., 1983). The authors also tried to encompass these findings within the Social Identity Theory, stating that «groups who feel their status is not threatened resolve the potential conflict in a more constructive manner by using fairness to equalise the groups». In line with these late findings, our first study (Vala, Monteiro and Lima, 1986, 1988) met the above mentioned behaviour patterns when dealing with asymmetrical professional groups engaged in an organisational conflict.

We thus argue that variables used in the above mentioned studies, namely group status, perceived intergroup stability and legitimacy are not sufficient to account for intergroup behaviour in all its complexity: dominant groups do not always present a strong outgroup discrimination, in the same way that dominated groups do not always engage in ingroup favouritism when an unstable and illegitimate perceived status structure is present.

We hypothesise that the consensual history of an intergroup conflict can be an important variable to broaden our understanding about groups behaviour in intergroup contexts. The history of the conflict encompasses the group successes and failures experienced in the past as well as a prospective view of future encounters, thus providing the groups with a frame of reference for the development of strategies to cope with a renewed conflicting situation. Th is history of the conflict variable cannot be confounded with the stable/unstable status variable, for a conflicting situation is one of overt competition, where the established balance between the groups is necessarily perceived as potentially modifiable or even reversible, thus unstable. The «history of the conflict» as a variable means that group members consensually perceive their history, either as a sequence of encounters with systematic (linear) success/failure outcomes or as a sequence of encounters with some proportion of success/failure outcomes for both groups (non-linear).

From the literature on group status and intergroup discrimination, two organisational studies with the mentioned opposite pattern of results, helped us on our theoretical analysis: Brown (1978) and Vala et al. (1988). We wondered if the history of the conflicts they reported could account for that divergence. In both studies two professional groups within the same company were engaged in an explicit conflict, both with the managerial board (to objectively raise their salaries) and between themselves (to maintain or enhance their relative wage status positions). In Vala’s study, the conflict took place in a transports company, and the outcomes of the conflict, systematically favoured the same dominant group, designing what has been named a «linear history of the conflict». Relative deprivation measures used to assess the intergroup patterns, showed that the lower status group yielded stronger outgroup discrimination than the higher status group.

In Brown’s study in an aircraft factory the same kind of conflict namely opposed the production and the development teams, respectively the lower and the higher status groups. Contrarily to our study, in this conflict the relative positions of the two groups have changed in the last years, designing a «non linear history of the conflict». TajfeFs matrices used by Brown to assess the intergroup behavioural intentions of the two groups showed, comparatively to Vala’s one, a reversed pattern of responses, where the higher status group yielded a strong outgroup discrimination and the lower status group a strong fairness display.

The two opposite patterns of results found by Brown (1978) and by Vala et al. (1988) in similarly conflicting unstable organisational contexts cannot be accounted by any of the previously listed relevant variables (group status, perceived stability and legitimacy). But, of course, the dependent variables were different.

In the two studies we present here, we have investigated the impact of this new variable - the history of the conflict - on intergroup discrimination strategies, social identity of group members and the relation between the two variables.

According to the empirical results previously reviewed, the only possible predictions are that asymmetrical groups will show more similar patterns of outgroup discrimination in a linear than in a non-linear history of the conflict condition, where comparability between them is most salient.

Two studies were conducted to test this hypothesis, one in a field setting, and another one in a experimental setting.

Study 1. Field Study.

Two companies were considered according to a linear or non-linear history criteria. In both cases, two occupational groups were in conflict, not only with the company managerial board, but also confronting each other in order to maintain or modify their relative wage status. The short term history of the conflict in one organisation shows that the relative position of the two groups was that of a consistent dominance of one of the groups over the other, and then it provides a good example of a conflict with a linear history. In the other company, both the present winner and the present loser have already experienced an equalitarian pattem of status relations. That is what we name a non-linear history of the conflict (specifically, a broken equality history pattern).

Method.

Subjects.

65 subjects, randomly chosen among the professional groups of the two companies, participated in this study. Subjects were individually interviewed and they were asked to fill in a questionnaire containing the two dependent measures.

Instruments.

Dependent measures included a simplified format of Tajfel matrices (Tajfel et al., 1971; Turner, 1978) which were introduced as a study on wage negotiation. Professional identity was also assessed.

Results.

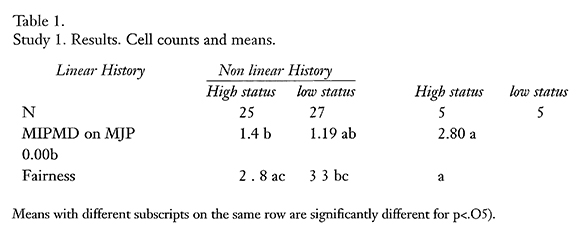

As predicted, intergroup discrimination results show a significant interaction effect, (MIPMD on MJP: (F(1,58)=6.03,p=.017) meaning that, while discrimination scores are similar for both groups in the linear history condition, they are significantly different in the non-linear history one. In fact, in the nonlinear history condition, members of the dominated group do not use this strategy at all, while members of the dominant one reinforce theirs.

Complementary, the Fairness results show significant effects for group status (F(1,58)=10.58; p=.002) and interaction(F(1,58)=8.03; p=.006), meaning that while in the linear condition both groups use this strategy in a similar way, in the non-linear condition only the dominated group relies on this strategy. As in the previous analysis, the main effect of the history of the conflict is non significant (F(1,58)=.520; p=.474).

These results show the importance of the variable «history of the conflict» in order to understand the discrimination pattern of asymmetrical groups. The traditional effect of higher levels of outgroup discrimination in the high status group was only found in the non-linear history condition.

To test our hypothesis in a more controlled environment, an experimental research was conducted.

Study 2. Laboratory Study.

In the second study, two variables were manipulated

- Group Status: the relative status position of two groups in a conflict, with two levels - dominant and dominated.

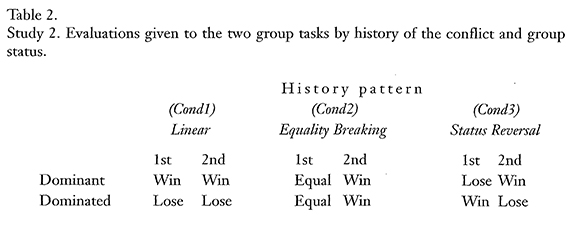

- History of the conflict: the sequence of failure and successes in the relationship between those two groups, in a limited period of time. We considered the two previous levels of the variable: - Linear History: in this type of history of the conflict, the relative status position of the two groups has not been changed in a period of time. - Non Linear History: Equality breaking History Pattern: in this type of history of the conflict, the present asymmetrical group status position was preceded by a equal status position. Behind these two situations, a third one was created, standing for a phenomenologically relevant one: - Non Linear History: Status Reversal History Pattern: in this type of history, the actual asymmetrical status position had already been revered in the past: the group which at present time is in the lower status position had already experienced the dominant position, and the opposite situation occurred with the presently dominant group.

Method.

Subjects: Fifty one subjects enrolled in a management and business administration course participated in this research. In order to replicate our field research, and to prevent any gender effect the subjects were all male.

Procedure.

Subgroup formation.

In each session, 10 subjects were randomly assigned to the experiment. The subjects assigned to each session carne from different classes of daily students, in order to prevent any effects due to previous social interactions. Greeted by the first experimenter, subjects were told: «You are going to participate in a decision making task. The goal of the exercise is to train and assess group decision making skills, an important managerial skill. In order to form the groups, I would like you to fill individually this questionnaire». A self-description questionnaire form was then presented to the subjects, and the second experimenter pretended to assess the answers and announced the sub-group constitution, according to a «group compatibility criteria» (in fact, subjects were randomly assigned to each subgroup, but this procedure was a way of strength ingroup solidarity). The two groups were then asked to occupy different tables in order to proceed the exercise. Members of each group were first asked to create a name for their group, and to record it a group consensus form.

Intergroup competition induction.

The second task was then presented to the subjects: «Now let us begin the group decision making exercise. But before that I would like to elucidate a very important aspect of this situation. Our University is developing a Quality Data Base including the name of students with specially good managerial skills. Decision making skills are considered an important part of a manager’s profile, and so your decisions will be assessed and the names of the students including the best of these two groups will be a part of this Quality Data Base. Now you will work on the first of the three decision making tasks. Please read carefully the problem, and discuss it within the group in order to reach a consensus on the best decision to make. Please record it on your group consensus form as well as the three main arguiu ents which sustain your decision. You have 15 minutes to accomplish this task. Group decision will be evaluated considering both the decision and the arguments.» Groups were given an exemplar of a risky shift problem.

Group status and history of the conflict manipulations.

After the group consensus, the second experimenter pretended to evaluate the answers, and, accordingly to the experimental condition (see Table 2) wrote on the group consensus forms the qualitative classification: «High score»/ «Médium score» / «Low score» (In fact, the classification was given randomly to the two groups).

The first experimenter gave the consensus forms to the groups, and stated clearly the supposed effectiveness of each group:

«Based on the criteria we used to correct your answers, the_[name of one of the groups] scored above the mean, and the____[name of the other group] scored below the mean. Thus, we can say that the____[first group] has won and the____[second group] has losen». (In Condition 2, Equality Breaking History Pattern, the two groups received a «Médium score», and were classified as matched)».

«Let’s now begin the second task. This problem has an higher level of difficulty, and you will have only 10 minutes to reach consensus.» The two groups received a second decision problem.

Once again, the answers were supposedly evaluated, and the scores and the relative positions of the two groups were clearly stated, in order to activate their relative status position and the history of the conflict between those two groups:

«Based on the same criteria, group scored above the mean, while group score below the mean. This time, group has won, and group . has losen. So until now, group had the following results: Win- Win (Cond1) / Equal-Win (Cond2)/ Lose-Win (Cond3), while group had the following results: Lose-Lose (Cond1) / Equal-Lose (cond2) / Win-Lose (Cond3). If we consider that the second task was more difficult than the first one, we can summarise the results and say that, at present time group is the winner, and group is the loser.»

Anticipation of conflict.

«We will now begin the last task. It is the most difficult one, and it is the one what will finally decide which of the two groups is the winner.»

Induction of status instability.

«We have already done this exercise many times, and we can say that the results of the last two tasks are not predictive of the results in this third one. It is a very different type of decision, and we ask you to engage hardly on the resolution of this problem.»

Dependent measures and debriefing.

«Before you begin this last task, we would like you to answer individually to some questions about your personal opinions concerning this exercise and the way things worked within your group. Once you all finish this questionnaire, we will begin the last task.»

Subjects answered a questionnaire which contains all the dependent measures. After that, subjects were fully debriefed.

Dependent measures.

Following the experimental manipulations, the participants were given a questionnaire including:

(a) Manipulation checking. Subjects were asked to State the previous results of their group (lst and 2nd tasks) and the actual relative position of their group (winner, loser, matched) as well as their perceptions of illegitimacy (How just do you consider the evaluation criteria in these tasks?) and instability of the situation (How do you see the possibility of your group change its previous results in the next task?), in 9 points scales. Al these measures aimed at checking the manipulation;

(b) Intergroup discrimination. As we have done in the field study, a simplified format of Tajfel matrices (Tajfel etal. 1971; Turner, 1978) was used. The matriceswere introduced as follows: «We are bargaining a scholarship in the amount of 250 thousand escudos with an international management company, to give to the best group in these exercises. Imagine you had the power to split that value between your group and the other group in this room. We will present to you some possibilities of sharing this amount of money. For each of the possibilities, please mark the one that you prefer. Three types of matrices were used: MD vs. MIP+MJP, MIPMD vs. MJP and F vs. MIP+MD.»

Results.

The checks on the manipulations showed that all subjects gave the correct response when they were asked to indicate the last result of their group (status checking) and the evolution of their group results (history checking). The situation was perceived a equally unstable by the subjects in the different experimental conditions and the dominated groups perceived the situation as more illegitimate (M=6. 12) than the dominant one (M=3.08) (F-group status(1,45)=35.90, p=.0005).

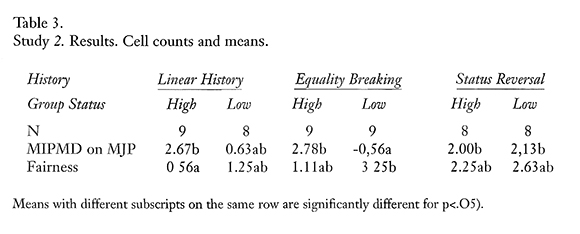

Intergroup Discrimination results are very similar to the field study. Intergroup discrimination results show a significant main effect for group status (MD on MIPMD: F(1,45)=29.37, p=.000; MIPMD on MJP: F(1,45)=12.10, p=.001) and an additional interaction effect (F(2,45)=3.67, p=.033). Similarly to the first study, this result shows that ingroup favouritism is similar for both groups in the linear condition, and that in the BEHP condition dominant groups discriminate more than the dominated ones.

As in the field study, results for the fairness strategy show a significant main effect for group status (F(1,45)=29.37, p=.000), which means higher reliance on this strategy in the dominated groups. It was also found a significant main effect for the history of conflict (F(l ,45)= 12.10, p=.001), standing for higher levels of fairness in the non-linear history conditions than in the linear ones.

Discussion.

Our results stressed the importance of the interaction between group status and history of the conflict between the groups in order to fully understand discrimination strategies.

We could State that the traditional effect of higher levels of discrimination yielded by dominant groups can only be understood if the history of the conflict is considered. As a matter of fact, this effect only shows up in a non-linear history, characterised by a past equalitarian status position between the groups which developed in a presently asymmetrical status position (Broken Equality History Pattern). Only then, dominant groups, both in field and in laboratory settings, showed extreme values of ingroup favouritism, and dominated groups lowered their discrimination pattern while promoted their fairness claims.

It should also be stressed that, in the other non-linear history pattern (Reversed Status) both dominant and dominated groups show the same differentiation strategy.

Such a pattern of results, consistently shown both in laboratory and in field settings, is not easily explained within the theoretical framework of Social Identity Model.

One other model based on SIT premises proposes a strategic approach towards understanding groups discrimination, and this model allows a coherent interpretation for our results. As a matter of fact, both the dominant group’s reduced statements of inequity and the dominated group’s radical propositions of fairness must be understood as a strategic response and not as a bias: the high status group tries to obscure ingroups’s advantages in order to maintain them, as well as the lower status group obscures his «intentions» of later ingroup favouritism. This model was first proposed by Van Knippenberg & Van Oers (1984), and was used more or less explicitly by some other authors. However, this kind of explanation does not allow the statement of any a priori hypothesis, but it only provides an a posteriori interpretation for whatever results are found.

The theoretical meaning of this new variable ( history of the conflict) remains, thus, unclear both in SIT restrict and extended frameworks. However, if we consider the relative solidity of the results showing the variance of intergroup discrimination with the perception of instability, it is worthwhile to conceive some kind of relationship of history of the conflict with this later variable. We thus propose that the history of the conflict should be understood as a specification of the situation when instability is clearly perceived as a characteristic of the situation for both groups in conflict. Realistic long term intergroup conflicts are a sound and persistent reality in human societies, claiming for a more and more comprehensive theoretical framework. We hope that future research on the effects of this new variable can contribute to a more comprehensive approach to those problems.

References

Amâncio, L. (1989). Social differentiation between «dominated» and «dominant» groups: Toward an integration of social stereotypes and social identity. European Journal of Social Psychology 19, 1-10. [ Links ]

Brantwaite, A., & Jones, M. (1975). Fairness an discrimination: English vs. Welsh. European Journal of Social Psychology, 5, 323-38. [ Links ]

Brantwaite, A., Doyle, S., & Lightbown, N. (1979). The balance between fairness and discrimination. European Journal of Social Psychology, 9,149-63. [ Links ]

Brown, R. J. (1978). Divided we fali: an analysis of relations between sections of a factory workforce. In H.Tajfel (Ed.), Differentiation between social givups. London: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Brown, R. J., & Smith, A. (1989). Perceptions of and by minority groups: the case of women in Academia. European Journal of Social Psychology, 19, 61-75. [ Links ]

Caddick, B. (1982). Perceived illegitimacy and intergroup relations. In Tajfel, H. (Ed.) Social identity and intergroup relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Commins, B., & Lockwood, J. (1979). The effects of status differences, favoured treatment and equity on intergroup comparisons. European Journal of Social Psychology, 9, 281- 9. [ Links ]

Gerard, H. B., & Hoyt, M. F. (1974). Distinctiveness of social categorization and attitude toward ingroup members. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29, 836-42. [ Links ]

Hewstone, M. R. C., & Ward, C. (1983). Ethnocentrism and causal attribution in Southeast Asia. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 48, 614-23. [ Links ]

Lorenzi-Cioldi, F., & Doise, W. (1991) Levels of analysis and social identity. In D. Abrams & M. A. Hogg (Eds.), Social identity theory. New York: Harvester. [ Links ]

Monteiro, M. B., Vala, J., & Lima, M. L. (1987). Intergroup conflict in organizational contexts: in search of the lost equity. [ Links ] Paper presented at the VIIth General Meeting of the E.A.E.S.P., Varna, Bulgaria.

Ng, S. H. (1980). The Social Psychology of Power. London: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Rosenberg, M., & Simmons, R.G. (1972). Black and white self-esteem: The urban school child. Washington DC: American Sociological Association.

Sachdev, I., & Bourhis, R.Y. (1985). Social categorization and power differentials in group relations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 15, 415-34. [ Links ]

Sachdev, I., & Bourhis, R.Y. (1987). Status differentials and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 17, 277-93. [ Links ]

Sherif, M. (1966). Group conflict and cooperation. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Simon, B., & Brown, R. J. (1987), Perceived intragroup homogeneity in minority - majority contexts. European Journal of Social Psychology, 53, 703-711. [ Links ]

Stoner, J. A. F. (1968). Risk and causious shifts in group decisions: The influence of widely held values. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 4,442-458. [ Links ]

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social identity and intergroup relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Tajfel, H., Flament, C., Billig, M. G., & Bundy, R. P. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1, 149-178. [ Links ]

Tajfel, H. ,& Turner, J. C. (1979). An integra tive theory of social conflict. In W. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.) The social psychology of intergroup relations. Chicago: Nelson Hall. [ Links ]

Turner, J. C. (1978). Social comparison, similarity and Ingroup favouritism. In H. Tajfel (Ed.) Differenciation between social groups. London: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Turner, J. C. (1980). Fairness or discrimination in intergroup behaviour? A reply to Branthwaite, Doyle and Lightbown. European Journal of Social Psychology, 10, 131-47. [ Links ]

Turner, J. C. (1981). The experimental social psychology of intergroup behaviour. In Turner, J.C. & H. Giles (Eds.), Intergroup behaviour Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Turner, J. C. (1988). Comments on Doise’s individual and social identities in intergroup relations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18, 113-16.

Vala, J. Monteiro, M. B., & Lima, M. L. (1988). Intergroup conflicts in an organizational context: How to survive the failure. In D. Canter, J. C. Jesuíno, L. Soczka, & M. Stephenson (Eds.) Environmental social psychology. Kluwer: Academic Publishers. [ Links ]

Van Knippenberg, A., & van Oers, H.(1984). Social identity end equity concerns in intergroup perceptions. British Journal of Social Psychology, 23, 301-310. [ Links ]