Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas

versão impressa ISSN 0873-6529

Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas no.87 Lisboa maio 2018

https://doi.org/10.7458/SPP20188710069

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Fault lines in education: dualization and diversification of pathways over 40 years of debate on education policy in Portugal

Direções e discursos: dualização de percursos e diversificação de vias educativas em 40 anos de debates sobre política educativa em Portugal

Directions et discours: dualisation des parcours et diversification des voies éducatives en 40 ans de débats sur la politique éducative au Portugal

Direcciones y discursos: dualidad de tramos y diversificación de las trayectorias educativas en 40 años de debates sobre política educativa em Portugal

Maria Álvares*

* Doutoranda no CIES-IUL, ISCTE-IUL, Lisbon, Portugal. E-mail: alvares.maria@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The creation of Vocational Education Courses in 2012 rekindled recurring debates that shaped the process of institutionalization of basic education in Portugal and brought to light tensions between the need to diversify education pathways and to ensure equity. A diachronic analysis of educational policies was conducted based on legislation, parliamentary speeches and newspaper articles. The analysis traced the process of dualization of education in Portugal and identified six different periods that help to better understand the reasons for the recent change. It also revealed a story where actors, narratives and solutions reappear, even in face of new realities, raising theoretical questions about what drives change in policy.

Keywords: diversification of educational pathways, policy change, equity in education, educational reforms.

RESUMO

Em 2012 a criação dos cursos vocacionais por parte do governo PSD/CDS suscitou o despertar de um debate há algum tempo adormecido, mas que marcou a institucionalização do sistema compreensivo em Portugal, evidenciando a tensão latente entre a necessidade de diversificar percursos educativos e formativos e, simultaneamente, de garantir a equidade e igualdade de oportunidades educativas. Com base em legislação, debates parlamentares e artigos de imprensa produzidos ao longo de 40 anos, o artigo visa analisar a trajetória das políticas implementadas e as batalhas discursivas travadas no processo de desenvolvimento do modelo compreensivo de educação, identificando-se seis diferentes momentos que ajudam compreender e interpretar a mudança ocorrida em 2012. Esta análise revela também uma história em que se repetem atores, narrativas e soluções, mesmo diante de novas realidades, levantando questões teóricas sobre o que impulsiona a mudança em políticas públicas.

Palavras-chave: equidade, modelo compreensivo de educação, diversificação de vias educativas e formativas, mudança em políticas públicas, institucionalismo histórico.

RÉSUMÉ

La création des filières dites vocationnelles en 2012 par le gouvernement PSD/CDS a relancé un débat que lon croyait clos depuis longtemps, mais qui a marqué linstitutionnalisation du système compréhensif au Portugal, en mettant en évidence la tension latente entre le besoin de diversifier les parcours éducatifs et formatifs et en même temps de garantir léquité et légalité des chances en matière déducation. En sappuyant sur la législation, les débats parlementaires et les articles de presse publiés au long de 40 ans, cet article analyse la trajectoire des politiques mises en uvre et les batailles discursives menées dans le processus de développement du modèle compréhensif déducation, en identifiant six moments différents qui aident à comprendre et à interpréter le changement survenu en 2012. Cette analyse révèle aussi une histoire où lon retrouve les acteurs, les discours et les solutions qui se répètent, même face à des réalités nouvelles, suscitant des questions théoriques sur ce qui pousse au changement des politiques publiques.

Mots-clés: équité, modèle compréhensif déducation, diversification des voies éducatives et formatives, changement de politiques publiques, institutionnalisme historique.

RESUMEN

En 2012 la creación de los cursos vocacionales por parte del gobierno PSD/CDS avivó el debate hace algún tiempo dormido, pero que marcó la institucionalización del sistema comprensivo en Portugal, poniendo en evidencia la tensión latente entre la necesidad de diversificar trayectorias educativas y formativas y, simultáneamente, garantizar la equidad e igualdad de oportunidades educativas. Con base en la legislación, debates parlamentarios y artículos de prensa producidos a lo largo de 40 años, el artículo tiene como objetivo analizar la trayectoria de las políticas implementadas y las batallas discursivas que tuvieron lugar en el proceso de desarrollo del modelo comprensivo de educación, identificándose seis diferentes momentos que ayudan a comprender e interpretar el cambio ocurrido en 2012. Este análisis también revela una historia en la que se repiten actores, narrativas y soluciones, incluso ante nuevas realidades, planteando cuestiones teóricas sobre lo que impulsa el cambio en políticas públicas.

Palabras-clave: equidad, modelo comprensivo de educación, diversificación de trayectos educativos y formativos, cambio en políticas públicas, institucionalismo histórico.

Introduction

The construction of modern education systems all over Europe occurred for three main reasons: (1) because it was central for the formation of citizens and national identity, (2) because it quickly became clear that the populations educational attainment generated economic development, and (3) because technological advances required a high availability of skilled labour (Nóvoa and Lawn, 2002; Green, 1997).[1]

In Portugal, the context of economic and technological growth that preceded the 1974 revolution and the countrys integration in the EU generated the need to feed the labour market with qualified workers and urged the promotion of school access to a large number of students, regardless of their social origin. There was a broad consensus regarding efforts to guarantee that the socioeconomic and cultural background of students didnt limit their ability to have long, meaningful and successful school paths. Equal opportunity became a central issue in educational policy. In the aftermath of the revolution, a comprehensive structure of educational provision was institutionalized. Basic and mandatory schooling was established for the first nine years and diversification of educational pathways postponed to secondary school, where technical and academic pathways coexisted, both enabling access to higher education. However, that was not always the case. Before the revolution, general, universal basic education was short-term and the two educational pathways reproduced the social origins of their attendees. Education was mostly seen as a sub-dimension of employment and labour market policies, and no issues of equity existed in the agenda (Murteira and Branquinho, 1970).

The analysis of the last 40 years of educational policies in Portugal must start with an overview of the state of affairs before the establishment of the basic education law in 1986. It is in that period that one can clearly identify the formation of the ideological oppositions that were latent, and yet evident, in the decades that followed.

The debate about the appropriateness of the comprehensive matrix of the Portuguese educational system and the benefits of pursuing a stronger and earlier diversification of educational pathways apparently a technical and pedagogical discussion has roots in different concepts of equity and the role of education (Antunes, 1997; Crato, 2006; Justino, 2010; Rodrigues, 2014). From a theoretical perspective, this finding raises questions about accounts of the recent changes in education as a result of a social learning processes in decision making or as a result of the crisis (Hall, 1993; Kuipers, 1990).

As in personal lives, change in policies frequently emerges as a result of long and matured processes, and past events have the power to make certain present choices more likely (Pierson, 1994). Without falling into essentialisms, the diachronic analysis of educational policies reveals a story where actors, institutions, narratives and solutions reappear, even in face of new realities. The hypothesis brought forward in this paper is that in the policy cycle from 2011 to 2015 it was the past not best evidence available or the special circumstances of the present that inspired policy choices. This suggests that, although not openly assumed, it was ideology and not policy learning that led to change in policies regarding the structure of educational provision.

The historical institutionalist perspective is based on the diachronical analysis of parliamentary debates, legislation and newspaper articles, as well as on research previously conducted regarding school dynamics offer and demand, education results, etc. and education policies. The documental corpus is composed of parliamentary debates, legislation and newspaper articles and was built by running a number of search words[2] through the public electronic database of Proceedings of Parliament of the Official Gazette of Portugal and of two widely read national newspapers (Público and Expresso). That process enabled the identification of the actors, themes and phases relevant to the analysis of dualization vs. diversification of educational pathways in the chosen timeframe.

The approach is interpretative, meaning that the policy argument is regarded as a patchwork of statements, interpretations, opinions and evaluations that connect the ideological context with data and information (Fisher, 2003). The documental corpus of research was analysed based on a framework analysis model, consisting of a four stage process: familiarization, an overview of all material gathered and identification of the thematic framework; indexing, the creation of analytical categories[3] for analysis and the coding and classification of information according to the categories created; charting, analysing the categorized information by theme (within categories) and case (across categories); and finally, interpretation, when the information analysed is used to create typologies, identify trends, and provide explanations for the phenomena under study (Ritchie and Spencer, 2002).

What dualization means in education

The concept of dualization is somewhat vague. Originally developed within the field of labour economics and labour market research, it has been increasingly used to describe processes of rising inequality regarding employment, access to social rights, welfare state and education that create or increase social barriers, dividing society into two groups: winners and losers (Davidsson and Naczyk, 2009). The peculiarity of these processes today is that they are not only spill-overs of inequality dynamics that emerge from economic relations, but are promoted by the State, which establishes rules and procedures that reinforce disparate access to rights and benefits for different groups (Palier and Thelen, 2010).

When applied to education, the concept can be used to characterize the institutionalization of policies that create parallel educational pathways, socially differentiated and unequally valued, crossing levels of education and leading to unequal labour market positions. Risking oversimplification, dualization is the opposite of equity and equal opportunities. Concerns about dualization emerge in response to policies aimed at diversifying educational offerings.

The economic growth of the last half century pressed the educational system to generate a wider group of qualified workers, which pushed it to incorporate differences in interests, sociocultural background, age, race and so forth. Simultaneously, the market demanded a broader array of qualifications and productive profiles. Both these new challenges found the fittest policy response within the diversification of educational pathways. Diversification of educational pathways responded not only to these challenges but also to problems of school failure and dropout rates that were attributed to an overemphasis in academic knowledge (Tessaring, 2004). Within and across countries, the objectives, the curricular contents and the structure of education became more diverse, with different institutions, curricular subjects and exit profiles becoming more available. This same trend, however, maintained various aspects of distinctiveness between educational models and, especially relevant for the current case, on the focus placed on equity (Lamb, 2011; Janmaat et al., 2013).

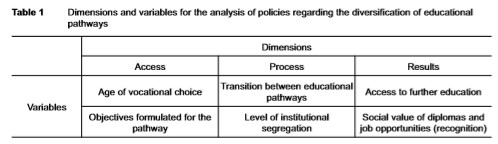

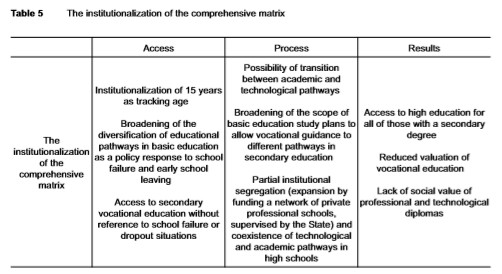

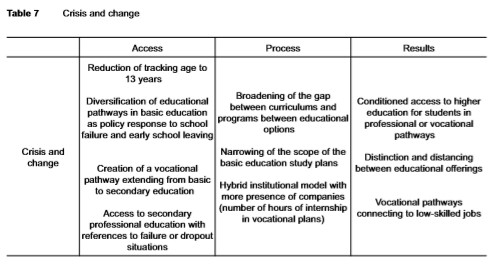

The focus on equity in policies for the diversification of educational pathways can be observed in elements of the design of educational policy measures that vary across countries and within countries throughout time.[4] When present, these elements can reduce risks of dualization and reveal an approach to equity (Lamb 2011). These elements relate to variables of access, process and results, as shown in table 1.

With regards to access, diversification of educational pathways differs from the process of dualization through factors related to the age in which the tracking to different pathways occurs and to some features of the process. Scientific research has long shown that, at an early age, vocational tracking seriously risks the transposition of social inequalities to the educational system (OECD, 2012). Young people from disadvantaged backgrounds tend to do less well with theoretical knowledge and, therefore, are guided to shorter and more practical pathways. In an elitist society where school diplomas matter, this leads them to less prestigious jobs with lower financial return. The earlier the tracking, the stronger the effect of social background in educational results. (e.g. Lemos, 2013; OECD, 2012). Also, diversification of educational pathways risks reinforcing social dualization processes when selection to different paths is based on academic performance relating weaker achievements to one path and school success to another and when selection practices are exclusively school based, without the input of families and other institutions or agents (Lamb, 2011).

Focusing on process variables, diversification policies differ from dualization policies by ensuring, in each curricular design subject areas, programmes, hours, etc. that there are realistic possibilities of shifts between options, safeguarding the transition between educational pathways. By defining a set of core subjects and contents in basic education, it is possible to avoid limiting choices once a student reaches secondary school. Institutional segregation, distinguishing students by school and/or certifying institutions, especially when resources are poorly distributed, can increase the effect of social inequalities in education (Lamb, 2011).

With respect to results, the way to pursue diversification of options without jeopardizing equity is by ensuring access to further education in all pathways and guaranteeing the existence of job opportunities by promoting the social value of diplomas.

Thus we can conclude that there are fundamental differences between policies of diversification of educational pathways and of educational dualization. The reconstruction of the debate that followed the process of democratization of education in Portugal enables the identification of the permanency of these issues throughout time.[5]

The unification/diversification debate in the Portuguese educational system

Background: the reform period of 1947/48

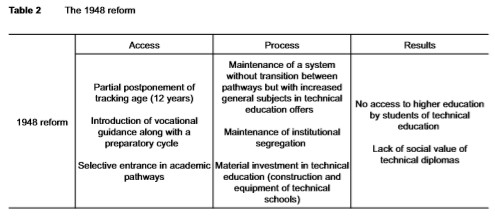

Some studies have highlighted the persistency of an elitist matrix in the Portuguese education system. This is noticeable in the devaluation of more practical pathways which have mainly been pursued by socially underprivileged students and appreciation of academic routes, with high rates of school dropout, and where social origin seems to have accounted for a major part of the school success (Sebastião, 2009; Abrantes, 2008). The background of the institutionalization period shows how a dualized educational system, typical of elitist models, has deep roots in Portuguese society. The break with this tradition began with the reforms of the academic pathway in 1947 (Decree No. 36 508/47, of September 17) and technical path in 1948 (Decree No. 37 029/48, of August 28) that created two additional degrees for acquisition of socio-cultural knowledge in vocational education. This amendment provided two more years of general education for students in technical courses, a partial postponement of the age of tracking. Still, the actual age remained at ten years old.

The public debates surrounding this alteration reveal two opposing views: on the one hand, employers who considered it crucial for the success of the industrialization process, and on the other, the traditionalist forces, which feared the changes would lead to increased expectations of social mobility for the underprivileged. The Soldiers of 26 movement[6] was the main objector in the National Assembly. The preparatory cycle of technical education, where humanistic and socio-cultural content would be taught, was considered scandalous for making of the manual worker a student and also a risk, since they could have the audacity to believe themselves to be graduates (MP Moura Relva, 1947 National Assembly, in Costa, 2005).

The most striking aspect was not the clear opposition between progressive and conservative forces, but the absence of a coalition for the defence of equal opportunity and the blatant defence of educational segregation as a way of upholding social inequality. The decision of 1948 lead to the maintenance of the elitist matrix and the dualized system that characterised the previous regime allowing, however, for subtle departures.

Except for the most conservative sectors, there was widespread acceptance of the reform. School principals reports make explicit references to the process of implementation, identifying it as the new education, making references to the new spirit of cycle of junior/preparatory education (Costa, 2005).

The reform by Veiga Simão

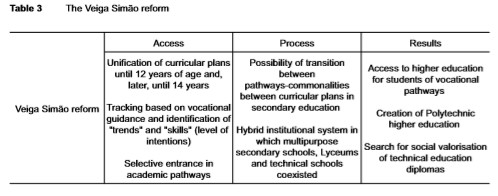

Contrary to what was proclaimed in 1948, it was only in 1973 that one can identify a real change. As widely reported and studied, this process was strongly influenced by the Mediterranean Regional Project and OECD recommendations for Portugal (Lemos, 2014). The latter pointed the need to promote equity and postpone specialization as a way to adapt to future needs, still somewhat uncertain, resulting from the expected economic development.

From 1964 to 1973 gradual changes ended with the approval of the Education Ministry Veiga Simãos reform in the last year (Law No. 5/73 of July 25). Preceding the 1974 revolution, this is the period of institutionalization of the comprehensive system of education.

By Decree-Law No. 45 810, of July 9, 1964, this reform built the Unified Preparatory Cycle of Secondary Education, materializing the postponement of tracking already in place for students of technical education. It established a model where a body of common disciplines existed integrating matter of a technical and professional nature in the Liceu. The role of secondary education was reformed, highlighting its dual function of preparing for higher education and for the labour market (e.g. Decree-Law No. 140-A/78, of June 22). Lifelong learning occupied a place on the agenda, which indicated a concern about the possibility of bypassing school verdicts.

In all analytical dimensions access, process and results and taking the chosen variables into account, Veiga Simãos reform represented a moment of strong change. It reflected a paradigm shift, with the implementation of policies that aimed to limit social reproduction and to promote greater equity in the educational system (Stoer, 1983). Nevertheless it should be stated that Veiga Simãos reform was never fully implemented, because the revolution took place in 1974.

The revolution and the 70s turn

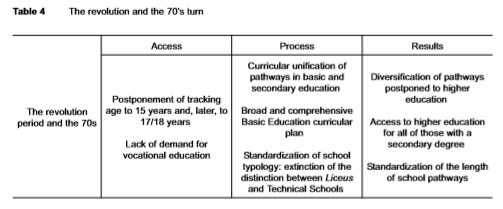

If in most political areas the 25th of April Revolution created great change, in relation to education, those changes were essentially incremental.

The emergence of educational studies and findings of scientific research are important in explaining the change: studies began to show that social inequalities were objectified and legitimized by school processes and policies of diversification of pathways were seen as threats to equal opportunities (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1964). The strategy was one of unification of basic and secondary education, in contrast to the previous periods efforts toward diversification but clearly in line with the overall orientation towards more equity that characterized it. Between 1975 and 1979 the various levels of education were gradually unified, finishing, in the last year, with the postponement of tracking until after the 10th and 11th grade. Professional training was postponed to tertiary education (Teodoro, 1999, 2007).

The deepening of the dynamics initiated in the previous period was pursued, but in the process the diversification of educational offerings was sacrificed and the need for technical workers with qualifications lower than graduation was unmet. A large number of young people were left behind, having failed in school or dropped out (Lemos, 2013).

The 90s, pathway diversification and pedagogical differentiation

The period from the late eighties to the turn of the century focused on the effectiveness of guidelines set out in 1986 in the Education Basic Law (Law No. 46/86, of October 14), in which the promotion of vocational education in secondary school was presented as the main challenge. In 1983 two types of pathways in secondary education were created: the professional courses of one year duration and the technical and professional ones, three years long. A common curricular structure was set for all options: (1) a general or socio-cultural component; (2) a specific or scientific discipline and (3) a technical or technological one (Decree No. 194-A/81, of October 21). Through this definition of a common structure a system of equivalence was instituted that lasted until 2004, and the transposition between pathways in secondary education became a real possibility. In the first two years the demand was very weak and up to 12% of the courses were not offered because of a lack of students. No more than one fifth of the students enrolled in secondary grades opted for professional courses (Azevedo, 1987). This period saw the most significant decrease in the overall and youth unemployment rate (respectively, from 8.6% and 18.5% in 1986 to 5.5 and 12.1% in 1993) and policymakers felt a pressing need to provide the labour market with highly skilled workers.[7]

Different conceptions of equal opportunities guided discussions and policies of basic and secondary education: in basic education consensus was around issues of access (equality of access), participation (equality of process), results (curriculum) and effects in life opportunities (equality of outputs), whereas in secondary education, there was a general agreement including among teacher unions that the issue of equal opportunities should be undisputed when it came to access and process, but regarding results and effects in life opportunities, principles of utility and labour market dynamics should be the main concerns (Antunes, 1997). According to Fatima Antunes (1997), underlying this option for diversification of pathways in secondary school was a view of inequalities as differences in interests, expectations, projects and aspirations that legitimized tracking as a way of promoting equality of opportunities. The strong correlation between the professions and social status of parents and the pathways chosen by/for the children was attributed to a lag in the process of adaptation of individual and collective mentalities to the change. Policymakers tended to disregard underlying inequalities in the distribution of resources, power and benefits that influenced those educational choices.

In 1995 the Socialist Party won the elections and Marçal Grilo became Minister of Education. This change saw the beginning of a very fruitful period where oppositions between public actors and loud discussions between epistemic communities experts, pedagogues and political commentators emerged. This rising debate was related to the intensity of legislative production, the expansion of educational sciences in Portugal and the promotion of participation initiatives, led by the socialist government.

Although in 1995 Portugal achieved the milestone of 100% enrolment at the age of 14, grade retention rates were unsustainably high, and about 35% of young people did not complete compulsory education set at 9th grade after 1986 (Benavente, Campiche, Seabra e Sebastião, 1994; GEPE, 2009). To many teachers and experts the rigidity of the curriculum was thought to be the root cause, so focus was on curricular changes. The changes followed a set of regulations and orders inherited from the previous political cycle, aimed to promote curriculum and program adaptation as educational compensation.

The alternative curricula an option that allowed schools to adapt the structure of each discipline and the content taught was first instituted in 1988 by Order No. 243/88, but only applicable under second chance education and to specific population groups. The expansion of this policy in regular basic education (Order No. 22/SEEI/96, of June 19) transformed the second half of the 90s into a relevant period to trace the history of dualization.

When submitting the Educational Pact for the Future in Parliament, the Communist Party immediately presented its opposition to alternative curricula. MP Luísa Mesquita echoed concerns of the scientific community, which argued that it marginalized students by placing [ ] on the ghetto of school failure all of those whom society has refused equal opportunities (DAR 1st series, No. 83/VII/1 1996/June/2769-2808). In fact, in 1992 Bourdieus work pointed to the production of young people excluded from the inside as a result of compensatory educational options. These reflected new forms of dominance and legitimation of inequalities through the educational system, by enabling social segregation by educational provision (Bourdieu and Champagne, 1992). In response to criticisms the socialist Secretary of State Ana Benavente, highlighted the need to provide answers for high dropout and emphasised differences: the alternative curricula were described as an emergency measure, aimed at facilitating the completion of basic education for children in school failure situations, with year repetitions and at risk of dropping out (DAR 1st series, No. 83/VII/1 1996/June/2769-2808). This type of curriculum would be offered by public schools and its implementation authorized, monitored and evaluated by the Ministry of Education. The proposed curricular structure would have to ensure that students [ ] achieve the essential objectives set for the basic education cycle in which they are integrated (Order No. 22/SEEI/96, of June 19). Students wishing not to continue studies would be exempt from final exams, but the possibility to continue studies in any secondary program was open to those taking national exams at the end of the 9th grade. According to official data, in 1996/97 94 schools had this option and, in the following year, 180 schools accounted for a total of 274 classes.[8]

The policy decision had little media coverage, and discussion of the expansion of the alternative curricula option was mostly absent among teachers and their unions. In a newspaper article of 1999 a school director referred to some resistance to this measure amongst teachers:[9] [ ] it was impossible to persuade more teachers to join a project that is a lot of work : program changes, extra-curricular activities, disciplinary adaptations, study tutoring, weekly meetings of teams. And he concluded: Teachers are not motivated (in Público newspaper, February 5, 1999).

The temporary and exceptional nature of the alternative curricula became clearer in the following period, when the flexible management of the curriculum, created with Decree-Law No. 6/2001, required clarification. In May 2002, the Director of the Basic Education Department,[10] Paulo Abrantes, stated that the curriculum [ ] should be flexible enough to account for all cases. But at this time, conditions needed to eliminate alternative curricula do not exist. Thus, there is no need for new legislation, since it is preferable to encourage schools to explore the Decree-Law No. 6/2001, adapting the class curriculum to problematic situations (Ministry of Education circular to the Board for Monitoring Management Flexible Curriculum, 2002).

Although the promotion of an Educational Pact for the Future enabled the identification of goals for change in curricular and organizational (accountability and evaluation) issues, no education reform was adopted. This was consistent with Javier Corraless observations on successful educational reforms. By applying Wilsons (1973) cost-benefit/interest group analysis to educational reforms, Corrales identified incentives for governments to pursue access educational reforms rise of supply, number of teachers or teachers salaries as opposed to quality reforms related to the reduction of student dropout or grade retention rates or teacher/school evaluation which faced strong opposition from powerful groups. Access reforms concentrated benefits and diffused costs, and quality reforms did the opposite. In quality reforms, teachers emerged as losers of privileges and became burdened with accountability requirements. Given their organization and blocking power, teachers made these quality reforms less likely (Corrales, 1999).

Replicating the analysis of the period based on a chosen set of variables, there are few identifiable changes from the previous period (table 5). The previous dynamics regarding access, process and results remained, and the overall orientation to implement skills assessment as opposed to content assessment deepened. Although the same possibility of access to higher education for students in professional[11] courses was preserved, the quality and preparation of professional courses arose as a critical point, suggesting a slight change in relation to the result variables.

Lack of change in educational results and criticism about the quality of learning in regular paths marked the end of this period. The government was accused of simplifying content and not guaranteeing quality. Education columnists raised their concerns: Carlos Fiolhais attributed the problem to the community of education experts (Fiolhais, 1997). João Queiró criticized the initiatives in order to lighten, increase the flexibility of, and relativize the academic content (Queiró, 1999).

The new century and the new tensions

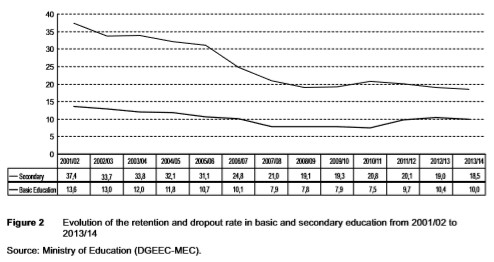

Despite the reduction of the dropout rate from 12.5% in 1991 to 2.7% in 2001, criticism regarding the quality of education dominated the early years of the new century. Criticism stemmed from Portugals low international ranking in terms of failure and early school leaving[12] in a PISA, OECD comparative study. From here on, international comparison played a central role in new educational initiatives (Serrão, 2014).

In 2001, the expert António Barreto published an opinion piece listing dogmas that restricted education policies (Barreto, 2001). Nefarious idea No. 9 is that vocational differentiation and disciplinary specialization should begin at the end of basic education, around fifteen years. This is the first time since the revolution when different ideologies openly clashed. A group of public figures[13] launched a Manifesto for the Education of the Republic and presented a portrait of catastrophe in education (Rodrigues et al., 2016). In opinion articles in the newspaper, the curriculum reform of 2001, based on the 90s guidelines was heavily criticized for being based on wrong educational theories (Valente, 2001). The preponderance of educational sciences was highlighted as the root cause of the bad results (Castilho, 2002). In an opinion piece, Maria Filomena Mónica, education expert, stated that, a civilized country has to ensure good basic education for all its citizens (that is what equal opportunities really means) while preserving universities for the intellectual elites (Mónica, 2003). In the United States the back to the basics movement of No Child Left Behind also gained impetus and supported these perspectives.

The next government,[14] a liberal-conservative (PSD-CDS) coalition, appointed David Justino as Minister of Education, and the pressure for a shift in educational policies continued. The discussion of the governments proposal to amend the Basic Law of Education in 2003 once again brought to the agenda the length of the educational cycles and tracking age (DAR 1st series, No. 140/IX/1 2003/July/5840-5872). The proposal was for the division of basic education into two cycles (the first of four grades and the second of two) and a compulsory secondary education, comprising two cycles of three grades.

Socialist MP and former Minister of Education Augusto Santos Silva viewed this as the critical point of the change and on the floor of Parliament, challenged the Minister of Education on the issue of curricular diversification in the new 1st cycle of secondary education: [ ] our position has been clearly stated: we do not conceive curricular unification as curricular standardization, but we do not accept that the logic of secondary education is, somehow, anticipated for children from 13 to 15 years of age (DAR 1st series, No. 140/IX/ 1 2003/July/5853).

Contradictory interpretations of the proposal seemed to exist within the advocating party. The minister promptly responded that the first cycle of the new secondary must be unified and the second cycle of the new secondary has to be diversified, therefore maintaining the tracking age at 16. However, Fernando Charrua, liberal (PSD) MP stated: With regards to strategies, the courage to ensure, for the first time, a parallel system to regular curricula, now dubbed vocational training, where students who do not complete basic education up to the age limit of 15 years will be compulsorily enrolled, must be pointed out (DAR 1st series, 140/IX/1 2003/Jul/5860). This perspective marked the return to an academic perspective that linked vocational and professional education to the prevention of school failure and early school leaving.

The lack of broad consensus in the parliamentary vote on the amendment to the Basic Law triggered the presidential veto. As a result pathway diversification was strengthened under the 1986 law, creating Education and Training Courses CEF (Joint Order No. 453/2004).

The 2004 reform (Decree-Law No. 74/04 of March 26) was inspired by the secondary curriculum revision of 2001, which had been suspended before implementation, and notwithstanding differences in some substantive aspects, the same policy orientation was apparent (Duarte, 2014). Following legislative elections in 2005, a socialist government took responsibility for implementation.

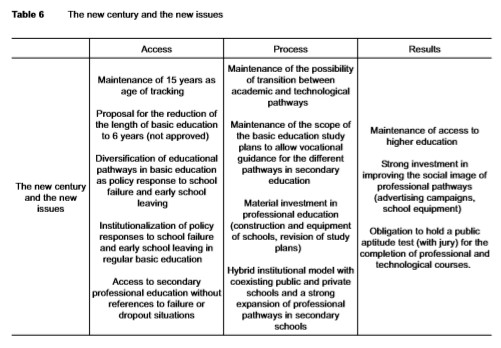

This period saw the greatest expansion of vocational education and training in secondary education, spurred by rising overall unemployment (that doubled from 4% in 2001 to 8% in 2007) and youth unemployment[15] (from 9.4% in 2001 to 16.6% in 2007). The number of students enrolled in dual certification options in secondary education increased 185% from 2006/07 to 2009/10, reaching 85% in the last year (Duarte, 2014). The curricular strategy followed the one inherited from the previous period, based on a unified structure in which access, process and results variables revealed similar conditions for students in scientific and technical routes.

In basic education, alternative curricula were reformulated in 2006 through Order No. 1/2006 establishing the Alternative Curriculum Pathways (PCA). The structure of the original diploma was maintained and access was limited to students with repeated years of retention, at risk of dropping out and/or with records of social integration problems at school. Some cost control measures seemed to have guided changes in the organization of the educational option, maintaining its objectives and curricular structure.

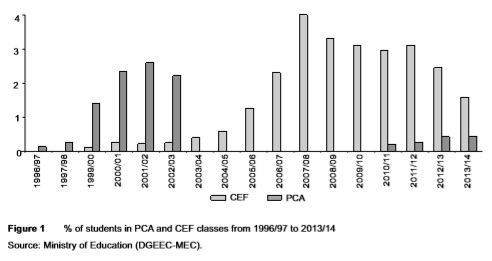

According to the evaluation study, the PCA classes tended to be composed of students for whom all support possibilities have been exhausted (Seabra et al., 2011). Statistical data[16] reveals that the number of students in PCA classes was always small and peaks from 2001 to 2003 with 2.6% of students in basic education enrolled. The CEF courses became more popular especially after 2006, and in 2007/08 were an option for 4% of students in basic education.

Keeping vocational and training opportunities in basic education as an option aimed at students at risk of dropping out this period, especially from 2006 onwards, stands out for the implementation of measures for the recovery of learning in regular classes. These have come to represent an additional support for students at risk for school failure, maintaining the original choice of a combined educational/training path. This was sought as a way to pursue curricular adaptation with less risk of ghettoization in non-qualified educational tracks. Two examples were the Recovery and Monitoring Plans (to be applied to students in failure situations) and the Turma Mais and Turma Fénix projects that created temporary groupings within classes.

These measures reduced early school leaving. According to Eurostat data, in 2003 the early school-leaving rate was 41.2%, dropping to 28.7% in 2010 (Sebastião and Álvares, 2015). In the 2009 PISA Portugal attained the OECD average scores in math proficiency, language and sciences for the first time and made the biggest progress in the various indicators. Portugal was ranked sixth out of 35 countries in its ability to minimize the impact of economic and social disparities in educational achievement, making considerable progress between 2000 and 2009, especially in the performance of young people from lower socio-economic backgrounds. In line with what several studies have demonstrated, it was possible to achieve greater overall educational results and improve equity (OECD, 2010).

In relation to the variables chosen to analyse change, there were no significant changes in this period and the chosen path reinforced previous dynamics.

Notwithstanding the improved results, similarly to what happened in the political change of 2002 the period attracted the same critics, in some cases, from the same public personalities (e.g. Valente, 2005; Crato, 2006). Again, the government was accused of reducing academic standards in order to improve success and of manipulating statistics.

Crisis and change

Despite PISAs favourable assessment, it was the lack of quality thesis that guided the educational policy proposals of the PSD-CDS coalition that won the 2011 elections. The government programme[17] announced the intention of replacing facilitation by effort, laxity by work, educational totalitarianism by scientific rigor, and indiscipline by discipline, pledging to draft a new Basic Law of Education. The continuous growth of the youth unemployment rate since 2002 was cited as evidence of the educational systems inadequacy, and again the proposed solution was to strengthen the connection between schools and the labour market.

In 2012, a basic education curricular reform was formulated (Decree-Law No. 139/2012, of July 5), aiming at (1) reducing the curricular dispersion; (2) strengthening core subject areas; and (3) focusing on core subject content. Subject areas related to the development of social and personal skills such as Civics and Supervised Study (Decree-Law No. 6/2001) were eliminated, even though evaluations of these options in 2006 and 2008 highlighted their importance in supporting students with social disadvantages (IESE, 2006; Bettencourt et al., 2008).

According to the advice[18] of the National Council for Education (CNE)[19] this reform broke with previous ones and represented a return to a traditional paradigm of academic rationalism that viewed the curriculum merely as a set of teaching materials and an organized structure of transmission. Regular basic education programs became more extensive and complex and national assessment tests were introduced in the 6th year (preparatory cycle of basic education) in 2011/12 and in the 4th year (last year of primary education) in 2012/13. In basic education these measures is contemporary with a growth in grade retention and dropout rates that since the introduction of tests of Portuguese and Mathematics in 2010/11 increased from 7.5% to 10%.

In 2012/2013, Ordinance No. 292-A/2012, of September 26, created the Vocational Education Courses. These were aimed at students from 13 years of age onwards who show constraints in regular education studies with two or more retentions in their schooling path. These courses started as a pilot project covering 243 students in the first year but in 2015 expanded to 24,500 students.

The legislation did not define the courses length, nor did they propose a defined program or any prerequisites, except a previous history of school failure and an age over 13 years. Having replaced the CEF option, the class load of these courses was much lower. The CEF type 2, aimed at young people in the 6th, 7th grade or uncompleted 8th grade, had a workload of 2109 hours. The vocational courses that led to the 9th grade diploma had a total workload of 1100 hours regardless of the level of education with which students began the program. The school or training centre that established the programs did not need to conform to program contents of regular options. Unlike the CEF, these vocational courses in basic education did not confer professional qualification.

There are several reasons why the introduction of these courses could be seen as a disruption with the unified model. Firstly, regarding access, the age of tracking was reduced to 13. If, as we have seen, vocational options in basic education already existed, these were limited to students from 15 years onwards and were oriented to recovery and preparation work so that students could opt for a school career in a non-conditioned way at the end of basic education. Secondly, although the referral of students should have taken place after a vocational assessment process guidance was likely to be based exclusively on the results of academic records, since schools faced a chronic shortage of psychologists and counsellors.

With regards to process variables, there is an increase in discrepancy between the workload and content taught in the new option versus the regular one, which materially prevented transitions between the two, given the small general and specific workload in target subjects of national exams and lack of programs or guidelines in these courses (CNE, 2012).

Considering result variables, this new option was limited. If successful in all subjects, vocational education students could access secondary-level professional education without sitting for the national exam and, even if they failed seven units, could attend vocational courses in this level of education.

The type of career option available also indicated increased difference; these were aimed at low-skilled professions with a narrow scope. For 2014 the ANQEP,[20] the national office responsible for vocational education, established as priority for vocational courses in secondary education, level two qualification of the National Qualifications Framework, which referred to functions based on basic factual knowledge, performing tasks and simple problem solving which enables a work under supervision. As job opportunities with higher labour market demand and, therefore, priority in course options, ANQEP set waiter and hotel employee, which replaced the media and information technology courses in high demand in earlier offerings.

Conclusion

The exercise proposed in this paper was to examine the history of Portuguese educational policies regarding the issue of unification versus diversification as a way to make sense of educational policies adopted since 2011, characterized as a change that contradicts the historical process (Sebastião et al., 2013; Estevão and Calado, 2015). By dividing the history into periods, it is possible to show the progress and setbacks of policies with respect to diversification of educational pathways in basic education, revealing tensions and political-ideological and educational dilemmas that such options comprise.

We have found that it is hard to come across an analytical model of change that can fully explain the policy evolution. If it is true that, since 2011, there has been significant change and, in fact, disruptions with processes that had been developing since before 1974 such as the continuous postponement of the age of tracking while others, such as the strategy of diversifying educational pathways to promote better results, appear to represent only incremental changes.

This type of evolution is, however, common. Policy change often emerges as a combination of continuities and ruptures. What is surprising is how change has been insinuating for so long and how adjustments in some parameters of a policy measure such as the compliance of options with possibilities of transition between pathways is clearly indicative of changes in the educational paradigm as a whole.

Recent diachronically conducted research has been able to identify types of change that are suited to describe periods that represent ruptures i.e. paradigm changes and yet, are subtle, incremental and sometimes, only perceived as mere adaptations (Streeck and Thelen, 2005). That description seems to fit the matter at hand. The preliminary findings point out to six different periods and three defining moments.

In the background period (1947-1948) and throughout the Veiga Simão reform, it is possible to identify the formation of two opposing views, present in the 40 subsequent years: one that defends a dualised structure, similar to that of the 1947/48 reform, and the other that defends the social-democratic model of unified comprehensive basic school, clear in the Veiga Simão reform. In the aftermath of the revolution the third period this second position was institutionalized in the Basic Law of Education. That marked the first defining moment.

It is only around 2000 with the publication of OECDs PISA, in which Portugal ranked poorly, that a window of opportunity appeared for the resurgence of the dualised solution: in the fourth period the length of the comprehensive structure was continuously questioned in newspaper articles by public figures and in the fifth period, by 2003, only a presidential veto blocked the change in the Education Basic Law that would enable the institutionalization of a dualised system. This was the second defining moment and one in which the confrontation ended with the defeat of the champions of change. In spite of the bump, we witness a long incremental change from 1986 until 2011, which promoted technical progress in policy solutions regarding the recovery of students at risk for failure or dropping out. As we have seen, in this period of incremental change and policy learning, Portugal witnessed the most rapid and sustained improvement of educational results both in equity and in quality.

In 2012 the sixth period began, and a new defining moment took place: again, is spite of the improvement of educational results, the narrative of the lack of quality and inefficiency of the educational system was invoked to promote a dualised educational solution that clashed with statements in the Education Basic Law (Law No. 46/86, of October 14).21 Austerity reasoning reached education, and policies to prevent and intervene in school failure situations that had been previously implemented with success, were reduced (Barata et al., 2012). Beyond the pressing need to decrease education costs, in the sixth period, there was evidence of change in the overall orientation of education policies. With limited opposition, education policies implemented from 2011 to 2015 - like the student statute (Sebastião and Campos, 2014) or national exams in primary education - revealed less orientation towards the equity and equal opportunities functions of education and a change in the direction of creating a two-tier education system with two parallel pathways: a highly competitive one with low survival rates, which can be seen as aiming to provide the labour market with highly skilled workers and to renew the reduced stock of insiders, and another pathway for all of those experiencing school failure, with lower requirements, more adjusted to the abundant positions of precarious and outsider workers in the labour market. In this setting, education policies are better understood as an instrument, a sub-dimension of employment and labour market policies, in line with a tendency previously observed in other countries to incorporate a rationale of economic competitiveness in education policies (Ball, 2001).

An overall feeling that the Portuguese are somehow to blame for the recent crisis (Capucha, et al., 2014) and the prescribed austerity reasoning help explain the limited opposition to the change in education policies in 2011. But little is new about the policy solution presented. In 2004 only the presidential veto prevented the amendment of the education basic law to enable changes in very much the same direction. In 2011, when the coalition defeated in 2005 came to power, it was mostly strategy that shifted. Although in its electoral programme the wining party (PSD) had promised the amendment of the education basic law, no legislative action was taken in that direction. The international support regarding previous educational policies (OECD, 2012) and the confrontational internal political environment did not favour engaging in an open debate about changes in the purposes and objectives of education that were in place. Instead, the approach was to circumvent opposition and the potential for a legislative veto by promoting adjustments in policy programmes, in setting policy instruments and techniques that, nevertheless, revealed the paradigmatic change.

Not built on consensus, changes made in 2011 are now at risk. Ever since the 2015 elections the Socialist Party, supported by a left wing majority in Parliament, has the mandate to implement a new agenda: ending national exams in basic education, promising to end vocational courses and again postponing tracking to the end of basic schooling. As of this articles publication date, it is still too early to say whether the new government can tackle the challenges ahead or if it will be trapped in the past. The hope remains that comparative science and critical views of history can highlight the effects of previous choices, to avoid bottlenecks and structural traps in policy design and implementation, and thus contribute to better policies and better outcomes.

References

Abrantes, Pedro (2008), Os Muros da Escola. As Distâncias e as Transições entre Ciclos, Lisbon, ISCTE Lisbon University Institute, PhD thesis. [ Links ]

Adão, Aúrea, and Maria José Remédios (2009), Memória para a frente, e o resto é lotaria dos exames: a reforma do ensino liceal em 1947, Revista Lusófona de Educação, 12 (12), pp. 41-64, retrieved from: http://revistas.ulusofona.pt/index.php/rleducacao/article/view/596/491 (accessed in 28/06/2015). [ Links ]

Álvares, Maria, and Alexandre Calado (2014), Insucesso e abandono escolar: os programas de apoio, in Maria de Lurdes Rodrigues (org.), 40 anos de Políticas de Educação em Portugal, vol. I: A Construção do Sistema Democrático de Ensino, pp. 197-223. Coimbra, Almedina. [ Links ]

ANQEP (2015), Resultados do Sistema de Antecipação de Necessidades de Qualificações Report, retrieved from: http://sanq.anqep.gov.pt/?page_id=699 (accessed in 29/06/2015). [ Links ]

Antunes, Fátima (1997), Discursos e projectos para a educação: diversificar, democratizar, universalizar, Análise Psicológica, XV (4), pp. 527-539, Lisbon, Instituto Português de Psicologia Aplicada. [ Links ]

Azevedo, Joaquim (1987), Dificuldades de Implantação Social do Ensino Técnico em Portugal. Avaliação do Ensino Técnico-Profissional, 1983-1986 (Report No. 3), Porto (manuscript). [ Links ]

Ball, Stephen J. (2001), Global policies and vernacular politics in education, Currículo sem Fronteiras, 1 (2), pp. 27-43. [ Links ]

Barata, Maria Clara, et al. (2012), Avaliação do Programa Mais Sucesso Escolar. Final Report, retrieved from Direção-Geral de Estatísticas de Educação e Ciência Ministério da Educação e Ciência: http://www.dgeec.mec.pt/np4/202/%7B$clientServletPath%7D/?newsId=268&fileName=PMSE_Alt_PDF.pdf (accessed in 28/06/2015). [ Links ]

Barreto, António (2001), Ideias nefastas para a educação, Público, April 3rd, retrieved from: http://pascal.iseg.utl.pt/~ncrato/Recortes/ABarreto_Publico_20020304.htm (last access in September 2016). [ Links ]

Benavente, Ana, Jean Campiche, Teresa Seabra e João Sebastião (1994), Renunciar à Escola. O Abandono Escolar no Ensino Básico, Lisboa, Fim de Século. [ Links ]

Benavot, Aaron (2006), The Diversification of Secondary Education. School Curricula in Comparative Perspective, Geneva, United Nations International Bureau of Education. [ Links ]

Bettencourt, Ana Maria, Fátima Guimarães, Jorge Pinto, and Tiago Caeiro (2008), Qualidade do Ensino e Prevenção do Abandono e Insucesso Escolares no 2.º e 3.º Ciclos do Ensino Básico. O Papel das Áreas Curriculares não Disciplinares (final report), Lisbon, Direção-Geral de Inovação e Desenvolvimento Curricular/ESE de Setúbal. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron (1964), Les Héritiers. Les Etudiants et la Culture, Paris, Minuit. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, Pierre, and Patrick Champagne (1992), Les exclus de lintérieur, Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales, 91-92, pp. 71-75, DOI: 10.3406/arss.1992.3008, retrieved from: http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/ arss_0335-5322_1992_num_91_1_3008 (accessed in 28/06/2015). [ Links ]

Capucha, Luís, Pedro Estêvão, Alexandre Calado, and Rita Capucha (2014), The role of stereotyping in public legitimation: the case of the PIGS label, Comparative Sociology, 13, pp. 482-502. [ Links ]

Castilho, Santana (2002), Prós e contras, Público, January 29, retrieved from: http://pascal.iseg.utl.pt/~ncrato/Recortes/SantanaCastilho_Publico_20030208.mht (last access in September 2016). [ Links ]

CNE Conselho Nacional de Educação (2012), Pareceres e Recomendações, Lisbon, Ministério da Educação. [ Links ]

Corrales, Javier (1999), The Politics of Education Reform. Bolstering the Supply and Demand; Overcoming Institutional Blocks, World Bank, The Education Reform and Management Series II (1). [ Links ]

Costa, Albérico Afonso (2005), A reforma de ensino profissional do pós-guerra da mudança necessária à mudança possível, Formar Revista dos Formadores, 52 (October), pp. 14-20. [ Links ]

Crato, Nuno (2006), O Eduquês em Discurso Directo Uma Crítica da Pedagogia Romântica e Constructivista, Lisbon, Gradiva. [ Links ]

Davidsson, Johan, and Marek Naczyk (2009), The ins and outs of dualization: a literature review, UO Barnett Papers in Social Research, Rec-WP 02/2009. [ Links ]

DGEEC Direção-Geral de Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência, Estatísticas da Educação 2013/2014, retrieved from: Ministério da Educação e Ciência: http://www.dgeec.mec.pt/np4/96/ (last access in September 2016). [ Links ]

Duarte, Alexandra (2014), Unificação e diversificação das vias de ensino, in Maria de Lurdes Rodrigues (org.), 40 Anos de Políticas de Educação em Portugal, vol. I: A Construção do Sistema Democrático de Ensino, Coimbra, Almedina. [ Links ]

Estevão, Pedro, e Alexandre Calado (2015), As políticas de Educação e o Memorando de Entendimento, in Maria de Lurdes Rodrigues e Pedro Adão e Silva (orgs.), Governar com a Troika. Políticas Públicas em Tempo de Austeridade, Coimbra, Almedina. [ Links ]

Fiolhais, Carlos (1997), Educação científica: os males e os remédios, Público, October 5, retrieved from: http://pascal.iseg.utl.pt/~ncrato/Recortes/CFiolhais_Publico_19971005.htm (last access in September 2016). [ Links ]

Fisher, F. (2003), Reframing Public Policy: Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices, New York, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

GEPE Gabinete de Estatísticas e Planeamento da Educação (2009), 50 Anos de Estatísticas de Educação, Lisbon, Editorial do Ministério da Educação. [ Links ]

Grácio, Rui (1985), Evolução política e sistema de ensino em Portugal: dos anos 60 aos anos 80, in João Loureiro (org.), O Futuro da Educação nas Novas Condições Sociais, Económicas e Tecnológicas, Aveiro, Universidade de Aveiro, pp. 53-154. [ Links ]

Grácio, Sérgio (1986), Política Educativa como Tecnologia Social. As Reformas do Ensino Técnico de 1948 a 1983, Lisbon, Livros Horizonte. [ Links ]

Green, Andy (1997), Education, Globalization and the Nation State, London, Macmillan. [ Links ]

Hall, Peter (1993), Policy paradigms, social learning, and the State: the case of economic policymaking in Britain, Comparative Politics, 25 (3), pp. 275-296, DOI: 10.2307/422246. [ Links ]

IESE Instituto de Estudos Sociais e Económicos (2006), Monitorização e Acompanhamento do Currículo Nacional do Ensino Básico para as Áreas Curriculares não Disciplinares (final report), Lisbon, Ministry of Education. [ Links ]

Janmaat, Jan Germen, Marie Duru-Bellat, Andy Green, and Phillipe Méhaut (orgs.) (2013), The Dynamics and Social Outcomes of Education Systems, Hampshire, Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Justino, David (2010), Difícil É Educá-los, Lisbon, Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos / Relógio DÁgua. [ Links ]

Kuipers, Sanneke (1990), The Crisis Imperative. Crisis Rhetoric and Welfare State Reform in Belgium and the Netherlands in the Early 1990s, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press. [ Links ]

Lamb, Stephen (2011), Pathways to school completion: an international comparison, in Stephen Lamb, Eifred Markussen, Richard Teese, John Polesel and Nina Sandberg (orgs.), School Dropout and Completion. International Comparative Studies in Theory and Policy, New York, Springer. [ Links ]

Lemos, Valter (2013), Políticas públicas de educação: equidade e sucesso escolar, Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas, 73, pp. 151-169, Lisbon, ISCTE, DOI: 10.7458/SPP2013732812 [ Links ]

Lemos, Valter (2014), A Influência da OCDE nas Políticas Públicas de Educação em Portugal, Lisbon, ISCTE-IUL, PhD, thesis, retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/10071/8434 (last access in September 2016).

Meuret, Denis (2001), A system of equity indicators for educational systems, in W. Hutmatcher, D. Cochrane and N. Bottani (orgs.), In Pursuit of Equity in Education. Using International Indicators to Compare Equity Policies, Dordrecht/ Boston/London, Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 134-164. [ Links ]

Mónica, Maria Filomena (2003), O mito e o pêndulo, Público, February 23, retrieved from: http://pascal.iseg.utl.pt/~ncrato/Recortes/MFMonica23022003.htm (last access in September 2016). [ Links ]

Murteira, Aurora, and Isilda Branquinho (1970), A mão-de-obra industrial e o desenvolvimento Português, Análise Social, VII (27-28), pp. 560-583. [ Links ]

Nóvoa, António, and Martin Lawn (orgs.) (2002), Fabricating Europe. The Formation of an Education Space, Dordrecht/Boston/London, Kluwer Academic Publishers. [ Links ]

OECD (2010), PISA 2009 Results, Paris, OECD. [ Links ]

OECD (2012), Equity and Quality in Education. Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools, Paris, OECD Publishing, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264130852-en [ Links ]

OECD (2015), Education Policy Outlook 2015: Portugal, Paris, OECD Publishing, retrieved from: http://www.oecd.org/education/(last access in September 2016). [ Links ]

OIT Organização Internacional do Trabalho (2012), A Crise do Emprego Jovem. Tempo de Agir, Conferência Internacional do Trabalho, relatório V. [ Links ]

Palier, Bruno, and Katheen Thelen (2010), Institutionalizing dualism: complementarities and change in France and Germany, Politics and Society, 38 (1), March, pp. 119-148, London, Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Pierson, Paul (1994), Dismantling the Welfare State? Reagan, Thatcher and the Politics of Retrenchment, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Queiró, João Filipe (1999), Educação: silêncios e problemas, Público, December 9, retrieved from: https://www.publico.pt/1999/12/09/jornal/educacao-silencios-e-problemas-127544 (last access in September 2016). [ Links ]

Ritchie, Jane, and Liz Spencer (2002), Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research, in A. Michael Huberman and Matthew B. Miles, The Qualitative Researchers Companion, retrieved from: http://methods.sagepub.com/book/ the-qualitative-researchers-companion (last access in September 2016). [ Links ]

Rodrigues, Maria de Lurdes (org.) (2014), 40 Anos de Políticas de Educação em Portugal, vol. I: A Construção do Sistema Democrático de Ensino, Coimbra, Almedina. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, Maria de Lurdes, et al. (2016), Educação. 30 anos de Lei de Bases, Lisbon, Mundos Sociais. [ Links ]

Sebastião, João (2009), Democratização do Ensino, Desigualdades Sociais e Trajectórias Escolares, Lisbon, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian / Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia. [ Links ]

Sebastião, João, et al. (2013), The asymmetrical educational consequences of economic recession in Southern Europe, communication presented in the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) General Conference of 2013 in Bordeaux, panel: Political Economy of Education: Redistributive Battles. [ Links ]

Sebastião, João, and Joana Campos (2014), O estatuto do aluno, in Maria de Lurdes Rodrigues (org.), 40 Anos de Políticas de Educação em Portugal, vol. I: A Construção do Sistema Democrático de Ensino, Coimbra, Almedina. [ Links ]

Sebastião, João, and Maria Álvares (2015), Wavering between hope and disenchantment: the case of early school leaving in Portugal, Scuola Democratica, 2/2015, pp. 439-454, DOI: 10.12828/80467 [ Links ]

Seabra, Teresa, Leonor Castro, Mafalda Gomes, and Ana Figueiredo (2011), Avaliação do Impacto das Turmas PCA e do Despacho 50, final report, Lisbon, Ministério da Educação. [ Links ]

Serrão, Anabela (2014), PISA: a avaliação e a definição de políticas educativas, in Maria de Lurdes Rodrigues (org.), 40 Anos de Políticas de Educação em Portugal, vol. I: A Construção do Sistema Democrático de Ensino, Coimbra, Almedina. [ Links ]

Stoer, Stephen (1983), A reforma Veiga Simão no ensino: projecto de desenvolvimento social ou disfarce humanista? Análise Social, XIX (77-78-79), pp. 793-822. [ Links ]

Streeck, Wolfgang, and Kathleen Thelen (orgs.) (2005), Beyond Continuity. Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Teodoro, António (1999), Os programas dos governos provisórios no campo da educação: de uma intenção de continuidade com a reforma Veiga Simão à elaboração de um programa para uma sociedade a caminho do socialismo, Educação, Sociedade e Culturas, 11, pp. 29-66. [ Links ]

Teodoro, António (2007), Revolução e utopia: um programa de acção no campo educativo para uma sociedade a caminho do socialismo Portugal 1975, Revista Lusófona de Educação, 10 (10), pp. 141-154, retrieved from: http://revistas.ulusofona.pt/index.php/ rleducacao/issue/view/67 (last access in September 2016). [ Links ]

Tessaring, Manfred (2004), Vocational Education and Training. Key to the Future: Lisbon-Copenhagen-Maastricht Mobilising for 2010, Cedefop document, Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/education/policies/2010/studies/cedefop_en.pdf (accessed in 28/06/2015). [ Links ]

Valente, Guilherme (2001), Ensinantes e aprendentes, Público, November 3. [ Links ]

Valente, Guilherme (2005), Eduquês escondido com ministra de fora, Público, December 12. [ Links ]

Plenary sessions of the Parliament from Diários da Assembleia da República (DAR): Official Gazette of Portugal Proceedings of Parliament

Diário da Assembleia da República (DAR), Gazette of Portugal Proceedings of Parliament 1st series, number 9, 3rd legislature, 1983/June/page 229

Diário da Assembleia da República (DAR), Gazette of Portugal Proceedings of Parliament 1st series, number 124, 3rd legislature, 1984/June/page 5326

Diário da Assembleia da República (DAR), Gazette of Portugal Proceedings of Parliament 1st series, number 83, 7th legislature, 1996/July/pages 2769-2808

Diário da Assembleia da República (DAR), Gazette of Portugal Proceedings of Parliament 1st series, number 140, 10th legislature, 2003/July/pages 5840-5872

Legislation

Law No. 5 of July 25, 1973 approves the bases of the reform of the education system and sets the extension of compulsory education up to 15 years

Law No. 46/86 of October 14 Education Basic Law

Decree-Law No. 37029 of August 25, 1947 promulgates the Statute of Professional Industrial and Commercial Education

Decree-Law No. 36507 of September 17, 1947 establishes the reform of secondary education

Decree-Law No. 45810 of July 9, 1964 expands compulsory education by creating the unified junior high school

Decree-Law No. 140-A of June 22, 1978 creates complementary courses in secondary education

Decree-Law No. 240 of July 19, 1980 creates the 12th year and extinguishes the introductory year of higher education

Decree No. 194-A of October 21, 1983 creates professional and technical education courses in secondary education

Decree-Law No. 26 of January 21, 1989 creates professional schools within the non-tertiary education

Decree-Law No. 286 of August 29, 1989 establishes the curriculum defined in the Education Basic Law

Decree-Law No. 6 of January 18, 2001 approves the curricular reorganization of basic education

Decree-Law No. 7 of January 18, 2001 establishes the guidelines of the organization and curricular management of general and technological courses of secondary education, as well as the assessment and the development of the national curriculum

Decree-Law No. 319 of August 23, 1991 approves the system of support for pupils with special educational needs who attend institutions of basic and secondary education

Decree-Law No. 74 of March 26, 2004 establishes the guiding principles of the organization and management of the curriculum and assessment of learning at a secondary level of education

Decree-Law No. 24 of February 6, 2006 amendment of Decree-Law No. 74/2004, of 26 March, which establishes the guiding principles of organization and curriculum management and assessment in secondary education

Decree-Law No. 139 of June 5, 2012 establishes the guiding principles of organization and management of curricula, assessment of knowledge and skills in basic and secondary education

Ordinance No. 194-A of October 21, 1983 creates professional, technical and professional courses as a pedagogical experience

Ordinance No. 243 of April 19, 1988 establishes the possibility of creation of alternative curricula as part of second chance education

Ordinance No. 162/ME of September 9, 1991 approves the student evaluation system in basic and secondary education

Ordinance No. 98 of June 20, 1992 approves the evaluation system of students in basic education

Ordinance No. 22/SEEI of June 19, 1996 sets the legal framework for Alternative Curricula as a measure to combat school failure and exclusion

Ordinance No. 453 of July 27, 2004 Joint Order of the Ministry of Education and of Social Security and Employment to create education and training courses

Ordinance No. 292-A of September 26, 2012 creates the educational offer of vocational courses in basic education, as a pilot experience in the academic year of 2012 -2013 and regulates the terms and conditions for its operation

Ordinance No. 276 of August 23, 2013 creates the educational offer of vocational courses at secondary level, as pilot experience in the academic year of 2013-2014, and regulates the standards organization, operation, evaluation and certification of this particular training.

Receção: 29 de setembro de 2016 Aprovação: 16 de junho de 2017

Notes

[1] This version of the paper takes into account useful comments provided by referees of the journal Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas for which I am thankful.

[2] The search words equity and education; diversification of educational pathways; comprehensive education system; alternative curricula; alternative curricular paths retrieved 20 parliamentary debates.

[3] In this case, the categories were of dimensions of access, process and results regarding education options in basic education (e.g.table1).

[4] This issue has been mainly approached in international comparativere search designs focusing on the classification of countries in educative models, comparing in two dimensions: hierarchical (basic and secondary education) and programmatic (comprehensive vs. technical) (Benavot, 2006; Lamb, 2011). The comparative analysis presented in this paper is different, focused on the national dynamics of development of policies of diversification of educational pathways in basic schooling.

[5] Interventions and speeches taken into account in this analysis, as well as newspaper articles and other sources of analysis of the debates were translated by the paper author.

[6] The movement Soldiers of 26 was constituted by the military involved in the coup that gave rise to the dictatorial regime lasting from1926 until 1974.

[7] OIT data: http://www.ilo.org/empelm/pubs/WCMS_114060/lang--de/index.htm

[8] Data provided by Ministry of Education (DGEEC-MEC).

[9] All citations are translated by the author.

[10] Departamento do Ensino Básico.

[11] When presenting in Parliament the Educational Pact for the Future, Minister of Education Marçal Grilo stated: The National Association of Private Professional Schools has, as this Government and I do, the distinct feeling that the strategy to consolidate the vocational system goes through a school network rationalization. You cannot keep some of these schools working, not because they are good orbad, whether or not they are well equipped, with many orfew students, but due to the promoters project it self (DAR1st series, No. 83/VII/11996/June/2769-2808). This position echoed existing concerns that some of these schools were established for the sole purpose of making use of EU funding.

[12] This point marked the beginning of a political and public attention cycle in which the focus was school dropouts in secondary education (named early school leaving) and in the quality of the preparation of that level of education.

[13] José Dias Urbano and Carlos Fiolhais, both physics college professors and Guilherme Valente, head publisher at Gradiva.

[14] XVconstitutional government which lasted from April 6 of 2002 to July 17 of 2004, due to the resignation of the prime minister.

[15] OIT data: http://www.ilo.org/empelm/pubs/WCMS_114060/lang--de/index.htm

[16] Ministry of Education data. It should be noted that there is a gap in the number of students that attended PCA classes from 2003/04 to 2009/10 due to changes in the data collection and processing.

[18] Published in the Official Gazette 8, 2nd series, of March 7, 2012.

[19] A consultation board formed by experts in education presided over by David Justino, Minister of Education from 2002 to 2004.

[20] National agency for qualification and professional education (Agência Nacional para a Qualificação e Ensino Profissional).