Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas

versión impresa ISSN 0873-6529

Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas no.75 Lisboa mayo 2014

https://doi.org/10.7458/SPP2014753578

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Clusters of religiosity of Portuguese undergraduate youth

Clusters de religiosidade da juventude universitária portuguesa

Clusters de religiosité des jeunes universitaires portugais

Clusters de religiosidad de los jóvenes universitarios portugueses

José Pereira Coutinho*

* Investigador da Númena. Taguspark — Núcleo central, 379, 2740-122, Porto Salvo. E-mail: jose.coutinho@numena.org.pt

ABSTRACT

This article presents results of the author’s PhD thesis based on religious beliefs and practices, and attitudes of towards marriage, life, and sexuality. The sample included 500 undergraduate students from public universities of Lisbon. Applying multiple correspondence analysis and cluster analysis to these beliefs, practices, and attitudes, three clusters or types of religiosity were produced: nuclear Catholics, intermediate Catholics, and non-Catholics. These clusters were characterised in terms of religious socialisation, as well as of non-Catholic beliefs and practices, and aspects of life. When crossed with these last items, the clusters were renamed respectively: socio-centred orthodox, ambitious heterodox, activist and hedonist non-believers.

Keywords secularisation, individualisation, socialisation, undergraduate youth.

RESUMO

Este artigo apresenta resultados da tese de doutoramento do autor, baseados nas crenças e práticas religiosas e nas atitudes em relação ao casamento, vida e sexualidade. A amostra incluiu 500 estudantes universitários das universidades públicas de Lisboa. Aplicando análise de correspondências múltiplas e análise de clusters a estas crenças, práticas e atitudes, foram produzidos três clusters ou tipos de religiosidade: católicos nucleares, católicos intermédios e não católicos. Estes clusters foram caracterizados em termos de socialização religiosa, assim como de crenças e práticas não católicas, e de aspetos da vida. Quando cruzados com estes últimos itens, os clusters foram redesignados respetivamente : ortodoxos sociocentrados, heterodoxos ambiciosos, descrentes activistas e descrentes hedonistas.

Palavras-chave secularização, individualização, socialização, juventude universitária.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article présente des résultats de la thèse de doctorat de l’auteur basée sur les croyances et les pratiques religieuses, et les attitudes relatives au mariage, la vie et la sexualité. L’échantillon a inclus 500 étudiants des universités publiques de Lisbonne. En appliquant l’analyse de correspondances multiples et l’analyse de clusters à ces croyances, pratiques et attitudes, trois clusters or types de religiosité ont été produits: les catholiques nucléaires, les catholiques intermédiaires et les non-catholiques. Ces clusters ont été caractérisés en termes des aspects de la socialisation religieuse, ainsi que des croyances et des pratiques non-catholiques, et des aspects de la vie. Après croisement avec ces derniers points, les clusters ont été redésignés respectivement: orthodoxes socio-centrés, hétérodoxes ambitieux, incrédules militants et incrédules hédonistes.

Mots-clés sécularisation, individualisation, socialisation, jeunes universitaires

RESUMEN

En este artículo se presenta resultados de la tesis doctoral del autor sobre las creencias y prácticas religiosas y actitudes hacia el matrimonio, la vida y la sexualidad. La muestra incluyó 500 estudiantes de las universidades públicas de Lisboa. Se aplicó análisis de correspondencias múltiples y análisis de clusters con estas creencias, prácticas y actitudes, dando tres clusters o tipos de religiosidad: católicos nucleares, católicos intermedios y no católicos. Estos clusters se caracterizaron en términos de socialización religiosa, así como de creencias y prácticas no católicas, y de aspectos de la vida. Cuando se cruzan con estos últimos aspectos, los clusters fueron designados de nuevo, respectivamente: ortodoxos socio-centrados, heterodoxos ambiciosos, e incrédulos activistas e incrédulos hedonistas.

Palabras-clave secularización, individualización, socialización, juventud universitaria.

Introduction

The passage from rural to industrial and then to post-industrial European societies had two religious outcomes. With first secularisation, traditional religiosity declined. With second secularisation or individualisation, religiosity lost its authoritarian feature and became individualised, turning into spi- rituality. Given that industrial society in Portugal was incipient, with almost direct transition from primary to tertiary society, both secularisations have possibly occurred simultaneously. The rise of middle classes, schooling, and living standards during the III Portuguese Republic allowed the dissemination of reflexive or late modernity. Portuguese censuses show that, in the last twenty years (1991-2011), both the percentage of Catholics and of non-religious people slightly rose (77.9% to 81%, and 2.7% to 6.9%, respectively) (INE, 1996: 422; 2012: 530). [1] Secularisation is in fact best supported by looking to some indicators of beliefs, practices, and attitudes, available in European Values Study (EVS). Between 1990 and 2008, for all age groups, both religious services attendance and rejection of homosexuality, abortion, divorce, and euthanasia decreased (EVS, 2010a, 2010b).[2] For the same period, beliefs in personal God, life after death, hell, heaven, and sin, as well as the importance of religion and of God increased for the youngest age group and decreased for the oldest age group.[3] In sum, older people continue to believe, to practise, and to follow Church’s norms more than younger people.

Actually, youth is the age group further away from religion. Being impossible to study the entire youth population, in this survey I analysed only the religiosity of undergraduate youth based on many indicators of Catholic beliefs and practices, as well as attitudes towards marriage, sexuality, and life. Using multivariate analysis I intended to engender clusters of religiosity for this empirical referent. Here, I wanted to measure the extension of secularisation in each cluster. Plus, I proposed to cross these clusters with indicators of socialisation, of non-Catholic beliefs and practices, and finally some aspects of life. Briefly, I wanted to measure the extent of religious socialisation and individualisation in each cluster.

Within youth population I opted by undergraduates for two reasons: first, their potential to generate more distinct clusters; second, the fact that it has been underexplored in the Portuguese case. First, as undergraduates come from a more privileged background that reflects a higher educational capital (Mauritti, 2002: 90-91; 2003: 17-20), possibly they are more open to both secularisations. Their greater exposure to modernity than less privileged classes probably permits greater variances in terms of traditional religiosity and spirituality. Second, since 1950s sociology of religion was connoted with the Catholic Church and its religious sociology. Secretariat of Religious Information and its Bulletin of Pastoral Information, constituted both in 1959, were the place to develop and to expose some researches. In this period a national survey concerning undergraduate youth was produced, which included some questions about religion (Codes, 1967). After the Revolution of 1974, sociology of religion gained autonomy and some increment in researching. Still, the only studies about undergraduate youth, in which religion was no more than one issue among others, were those of Figueiredo (1987) and Figueiredo et al. (2001) at national level, Silva and Monteiro (2000), and Fernandes (2001), at local level.

The first problem when dealing with religiosity is to select the dimensions to compose it. The definition and measurement of religiosity has occupied many scholars throughout the last decades. In the first studies, religiosity was measured through a unique indicator (Mass attendance). French sociologist Gabriel Le Bras, whose first work appeared in 1931 (Le Bras, 1931) marked the European sociology of religion throughout the next decades, including Portugal during the 1950s and 1960s. The north-American Fichter in the 1950s developed the first multidimensional approach to religiosity, followed later especially by his countrymen Glock and Stark in the 1960s. These three academics showed fine perspectives to approach the dimensions of religiosity. For all, dimensions of beliefs, practices, and attitudes were common (Fichter, 1969: 176; Glock and Stark, 1969: 20-21). Although their oldness, they keep their theoretical validity.

The second problem is to choose the indicators. The best sources of rough data about religion continue to be international databases: European Social Survey (ESS), European Values Study (EVS), and International Social Survey Programme (ISSP), mainly the last two due to their larger amount of indicators. Though their vast quantity of data and the presence of some Catholic beliefs and practices, as well as some attitudes above referred, these indicators are not enough to comprehend the Catholic religious field. Although authors disagree about the indicators required to measure religiosity (e.g. Rinaman et al., 2009: 419-420; Halman, 2003: 270; Cornwall et al., 1986: 228), the indicators used were chosen simultaneously to stand for the key features of Catholicism and for the defining features that distinguish this faith from other religions and Christian confessions. The indicators offered by these databases were complemented essentially by studies about Spanish youth’s religiosity (Blasco et al., 2006; González-Anleo et al., 2004b).

The third and last problem is the generation of groups or clusters inside a population. Clusters of religiosity are not being widely developed, varying Christian or Catholic clusters between three, five, or six groups (Imaz, 2004; Fulton, 2000; Campiche et al., 1997; Lambert et al., 1997; Lambert, 1992). Lambert et al. (1997: 127) argued that multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) (the multivariate technique used in this study) generates always three poles. So, Fulton (2000: 23) with his three Catholic clusters (nuclear Catholics, intermediate Catholics, and apostates) and Lambert et al. (1997: 127-130) with their three Christian clusters (confessional Christians, cultural Christians, and secular humanists), are until now the best solutions to segment Catholic or Christian youth. Nevertheless, both studies show some limitations: the first did not include Portugal and was based on a reduced sample of life histories; the second was grounded on the second round of EVS (1990); both did not survey undergraduate youth and used a few indicators of belief and practice.

Secularisation, individualisation, and socialisation

Secularisation theory had its major development during the 1960s, with Europeans Wilson, Berger, and Luckmann as its main supporters. For them, modernity’s rationalisation and differentiation brought or would bring inevitable and unstoppable global decreasing of religiosity in terms of beliefs and practices. Though, the increase of empirical evidence that secularisation is not inevitable and generalised forced sociologists to reformulate this theory. Thus, it became less one-dimensional and more complex, summoning different variables to explain not the end but the reorganisation of religion (Tschannen, 1992: 296). Dobbelaere presented since 1980s one of the main and influent three-dimensional theories, showing secularisation as a complex process that can be analysed with some independence in three levels (macro, meso, and micro) (Willaime, 2006: 764). In the middle of 1990s, Chaves (1994) produced an important contribution for secularisation, considering it no longer the decline of religiosity but of religious authority.

Actually, religious reality could not be considered a simple, linear and universal effect of modernity. In fact, influential academics as Eisenstadt (2000) and Taylor (1995) regard modernity in multiple ways, depending on each culture’s features. Thus, the link between modernity and religiosity is not simple, but diversified. For Lambert (1999), modernity had four consequences on religion: decline, adaptation, innovation, and reaction. For instance, both modernity and religion can reinforce each other, as in Pentecostalism (Martin, 2011: 8-9) or in the USA (Berger et al., 2010: 15-21); or they can be antagonist, as in Europe. Following Berger (2008: 24) and Davie (2006: 291), I consider secularisation mainly the exceptional process of Europe’s religious evolution.

There are three groups regarding their position towards secularisation. There are authors like Berger that changed field, from chief supporter of secularisation (Berger, 1990 [1967]) to upholder of Europe’s exceptional case theory (Berger, 2008). Others like Bruce kept his strong position in favour of secularisation since 1990s (Bruce, 1992) until now (Bruce, 2011). Or others like Martin that was always sceptical of secularisation, since the middle of 1960s when he offered his first critique of secularisation (Martin, 1965). Following Popper’s criticism of historicism, he argued that secularisation was an ideological and philosophical imposition on history (Martin, 2005: 19). For him, religious evolution depends on the degree of pluralism in each country: where church and state were separated and where there was religious pluralism and competition, religion flourished most luxuriantly (Martin, 2005: 21).

Following Taylor (1991), Heelas and Woodhead (2005) argued that in modern culture there is a subjective turn from life-as forms of the sacred to subjective-life forms of the sacred. This spiritual revolution turns emphasis on transcendent to inner sources of significance and authority. So life-as religion decreases while subjective-life spirituality increases. In this context, individualisation or second secularisation can be comprehended. Individual is now the sovereign of his/her destiny and does not need to conform to higher authorities in order to reach his/her happiness or to find meaning to his/her life. So individualisation, product of privatisation (the existence of religion only in the private sphere), conjugated with the decline of religious authority and the enlargement of pluralisation (the existence of a religious market), brought religious bricolage, the construction of religion à la carte, mingling doctrines and practices, and developing different degrees of religiosity (Dobbelaere, 1999: 239-241). These elements can be found in New Age, like re-incarnation and yoga, or in popular culture, like superstitions and horoscope, or in the modern world, like consumption and success. Lastly, the concepts of pilgrim and convert are important to understand today’s religion in motion, according to Hervieu-Léger (2005). For the pilgrim, practice is volunteer, personal, plastic, and mobile, and no longer mandatory, communitarian, fixed, and territorially bounded. For the convert, religious identities are also in movement, observed by the change, the entrance, and the deepening into certain religion.

Socialisation is the last sociological concept to present. According to Parsons, socialisation is the process by which individuals internalise social values and learn basic social expectations, which define specific social roles (Scott, 1997: 45). Within religious socialisation, beliefs, practices, and attitudes towards Church’s norms are absorbed. Family is fundamental in general socialisation (González-Anleo and González-Anleo, 2008: 41; Cerezo and Serrano, 2006: 36; Pérez-Delgado, 2006: 87; Casanova, 2003a: 168-169; Casanova, 2003b: 182-183) as well as in religious one (Blasco, 2004: 162; González-Anleo, 2004a: 42). Is the transformation of traditional family in the last decades altering religious transmission? The concepts ‘lineage of belief’ and ‘chain of memory’ from Hervieu-Léger may be helpful to give some insight to this question. According to Hervieu-Léger (1998: 216-218), religious group is a lineage of belief, which constitutes and reproduces itself based on memory, a continuation of the past (anamnesis). Certain belief is transmitted from one generation to another, as well as norms, orientations, and values. A ‘chain of memory’ is created, being transmission the motion by which religion constitutes as such over time. So, firstly today individuals produce their relationship with the lineage of belief from which they take their identity. Thus, they are less influenced by family’s and other institutions’ norms. Secondly, modification in family structure probably induces an even greater detachment from religious memory. In fact, as religious marriage dwindles, possibly aloofness to religion increases, since marriage is the enrolling rite of passage to a lineage of belief. Though, there are always religious people that come from none or less religious families.

Method

In terms of population, Portuguese undergraduate students are the target of this study. Given the practical impossibility of surveying the entire population, I opted for finalist undergraduate students in state universities. Indeed, 76% of Portuguese undergraduate students are in the public system, of which 47% are in state universities (2008/09 figures).[4] Likewise, in Lisbon region (distrito), these percentages stand at 66% and 54%, respectively. In order to gather a representative sample of the inquired population, I resorted first to quota one, a non-random sampling method, with the following criteria: the disciplinary area (sciences, health, etc.), the course, the institution, and the gender. The next step was to apply a random simple sampling, though teachers’ availability imposed a convenience sampling. Initially, I hoped to randomly select the teachers, but soon I realised that this would have been very cumbersome and would not significantly improve the reliability of the sample.[5] Working with time constraints, I obtained a sample of 500 students, aged between 19 and 25, with three-quarters being of 20-21 years old; 47% male and 53% female. The data was gathered during March 2010.

In terms of results, I had two goals. First, cluster the sample by religiosity and measure the level of secularisation for each cluster. Second, characterise the sample in terms of individualisation (non-Catholic beliefs and practices, and aspects of life) and socialisation. For the first goal, I applied MCA with cluster analysis (CA). First, I opted to produce separate clusters for beliefs, practices, attitudes, and religiosity, instead of producing only one set of clusters of religiosity, for two reasons. In the first place, for theoretical reasons, I pretended to test if each dimension of religiosity is important by itself, which is checked through inertia and also Cronbach’s Alpha. In the second place, for operational reasons, it is more practicable to scatter the thirty-six indicators by each dimension of religiosity. In fact, these indicators together would produce an unreadable array of data. For the second goal, I applied Chi-square tests in order to evince the differences of each cluster in terms of those parameters above referred, which are very important to deepen their characterisation.

MCA is a topological method that converts multidimensional space into a two-dimensional in which the categories of input variables are grouped. It works as alternative to principal components analysis (PCA) whenever variables are qualitative, as in this study. Dimensions are the structural axes of the space in analysis and they have some variables with stronger explanatory powers, that is, variables that differentiate more the objects (respondents) between them. As in PCA, a dimension can be seen as a new variable that brings together the input variables. The degree of differentiation or discrimination of objects is measured by the inertia, which varies between zero and one. The most interesting variables have a value closer to one and are greater than, or equal to, the inertia. Other important measure is Cronbach’s Alpha, which gauges the reliability of the model adjustment, serving as a complement to the inertia. Higher Cronbach’s Alphas imply better model adjustment.[6] If topological graph of MCA shows distinct types, then the final step is to implement cluster analysis to MCA in order to create and to quantify them. To determine the number of clusters, I applied Ward’s method and I resorted to K-means method to optimise the solution. In each kind of variables, firstly MCA is applied. If variables discriminate well the respondents (checked by inertia) and if the model adjustment is reliable (checked by Cronbach’s Alpha), secondly cluster analysis is applied to each group. Finally, the clusters of beliefs, practices, and attitudes are used as variables for the last MCA, in similar process.

There are a few tests to evaluate the relationship between two variables. When both variables are nominal or at least the dependent variable is nominal, Chi-square test (c2) is used. In fact, the dependent variable ‘clusters of religiosity’ used for all the tests in this article is nominal. To apply this test there are some premises that have to be followed: population larger than 20, all expected frequencies higher than 1, at least 80% of expected frequencies equal or higher than 5 (Maroco, 2010: 107). When at least one of these premises is not adopted, Fisher’s test (Phi) is applied as replacement (Maroco, 2010: 111-112).

Results and discussion

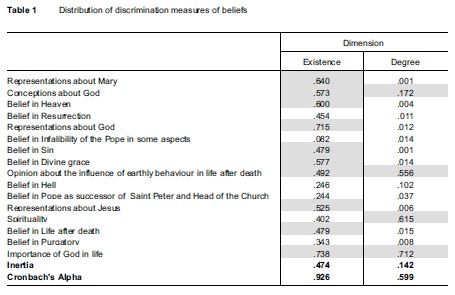

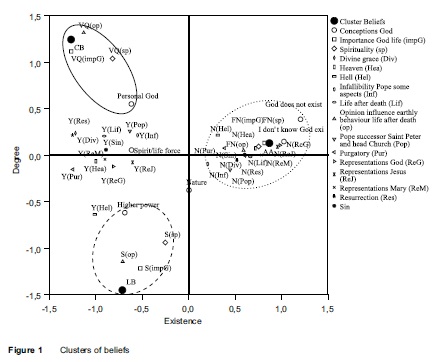

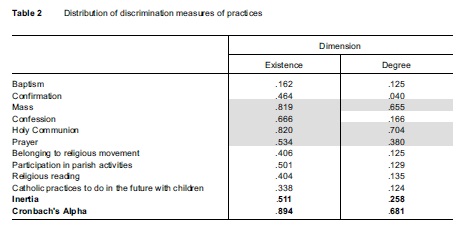

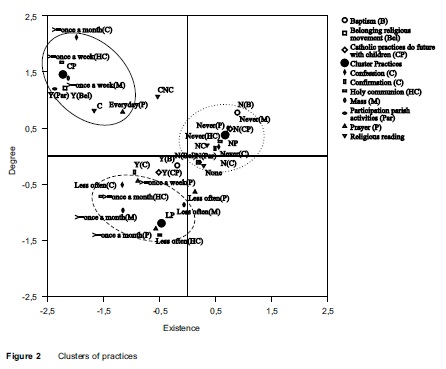

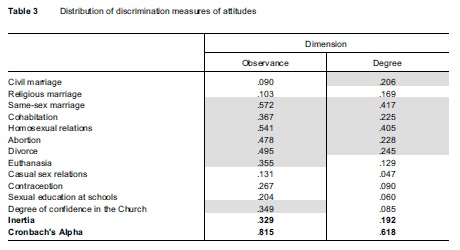

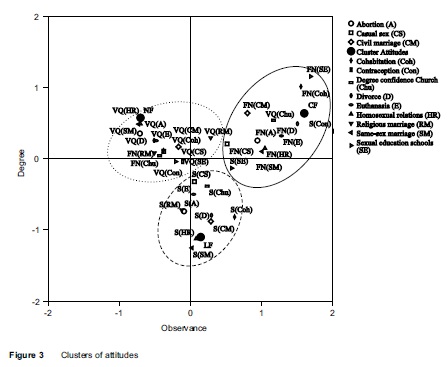

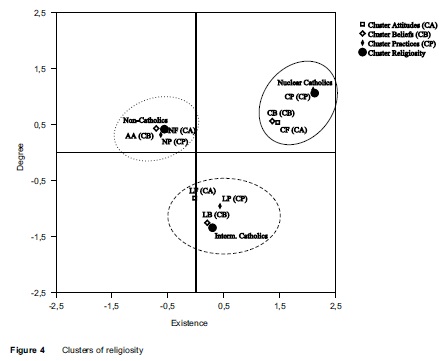

To analyse the results linked to the first goal I focused on the values of inertia and on Cronbach’s Alpha. Since it is not possible to insert more than seven tables and graphs, I opted to include only the tables of discrimination measures and the graphs of clusters. Thus, the graphs of discrimination measures were excluded, as well as graphs about cluster analysis. For tables of discrimination measures, in grey are the variables with values higher than inertia. For graphs of clusters, the most religious clusters are represented with a full line; the least religious clusters are represented with a dashed line; the non-religious clusters are represented with a dotted line.

The set of clusters of beliefs makes sense by itself, since Cronbach’s Alpha is at least high for dimension 1 (low for dimension 2) and there are many variables with high values of inertia (table 1). Dimension 1 can be denominated ‘Existence’ of beliefs, since its central axe divides believers from non-believers. Dimension 2 can be named ‘Degree’ of beliefs, because its central axe separates two kinds of believers: convinced believers and loose believers. In short, the clusters of beliefs can be characterised as follows (figure 1):

Cluster ‘Atheists/Agnostics’ (AA) (50.6%): belief and importance of God in life is inexistent or meets strong scepticism; all the dogmatic beliefs are absent (mainly about God, Jesus and Mary, Heaven and the Divine grace). Cluster ‘Loose believers’ (LB) (27.2%): believe in God as a higher power and acknowledge the importance of God in life, the spirituality, and the influence of earthly behaviour in life after death. Cluster ‘Convinced believers’ (CB) (22.2%): strongly believe in a personal God and accept the importance of God in life, the spirituality, and the influence of earthly behaviour in life after death.

All dogmatic beliefs, used in this study as two-answer questions, are in-between LB and CB. They are insufficient to separate the least believers from the most believers. Probably if they were five-answer questions, like ‘degree of spirituality’, their distribution could be similar to this.

Like in the previous clustering, on the one hand the set of clusters of practices makes sense by itself, and on the other hand dimensions 1 and 2 are ‘Existence’ and ‘Degree’, for the same reasons (table 2). In short, the clusters of practices can be characterised as follows (figure 2):

Cluster ‘Non-practitioners’ (NP) (57.6%): non-baptised and non-confirmed; never assist Mass, nor take Holy Communion, nor confess themselves, nor pray; do not belong to any religious movements nor participate in any parish activities; never read religious texts; avow that in the future they will not have any Catholic practice with their future children. Cluster ‘Convinced practitioners’ (CP) (10.8%): attend Mass and take Holy Communion at least once a week; confess themselves at least once a month; pray daily; belong to religious movements and participate in parish activities; read religious texts. Cluster ‘Loose practitioners’ (LP) (22.2%): attend Mass and take Holy Communion, even if sometimes less than once a month; confess themselves, even if not very often; pray regularly (at least once a month).

Unlike clusters of beliefs, two-answer questions may help to differentiate CP from LP, as ‘Belonging to religious movement’, ‘Participation in parish activities’ and ‘Religious reading’.

Unlike previous clusterings, the quality of set of clusters of attitudes is unobvious, since the highest value of inertia is 0.572, although acceptable Cronbach’s Alphas (table 3). Dimension 1 is denominated ‘Observance’ of Church’s rules, since its central axe divides non-followers of Church’s rules from followers. Dimension 2 is named ‘Degree’ of observance of Church’s rules, because its central axe separates two kinds of followers: convinced followers and loose followers. Clusters of attitudes can be characterised as follows (figure 3):

Cluster ‘Convinced followers’ (CF) (17.8%): strongly disapprove same-sex marriage, homosexual relations, divorce, abortion, cohabitation, euthanasia, civil marriage, and strongly (or quite strongly) rely on the Church. Cluster ‘Loose followers’ (LF) (34.8%): agree with same-sex marriage, homosexual relations, divorce, abortion, cohabitation, euthanasia, civil marriage, and put some confidence in the Church. Cluster ‘Non-followers’ (NF) (47.4%): strongly or quite strongly agree with same-sex marriage, homosexual relations, divorce, abortion, cohabitation, euthanasia, civil marriage, and have little or no confidence in the Church.

The clusters of religiosity[7] are mainly produced by variables ‘clusters of beliefs’ and ‘clusters of practices’, since variable ‘clusters of attitudes’ have values lower than inertia for both dimensions. Once again, dimension 1 and 2 are ‘Existence’ of religiosity and ‘Degree’ of religiosity, for the same reasons. Clusters of religiosity can be characterised as follows (figure 4):

Cluster ‘Nuclear Catholics’ (NC) (26%): composed by cluster CB of beliefs, cluster CP of practices, and cluster CF of attitudes. In short, this cluster reunites the believing and practising Catholics, who follow Church’s rules. Cluster ‘Intermediate Catholics’ (IC) (19.6%): composed by cluster LB of beliefs, cluster LP of practices, and cluster LF of attitudes. In short, this is the cluster of the somewhat believing and practising Catholics, who sometimes follow Church’s rules. Cluster ‘Non-Catholics’ (Non-C) (54.4%): composed by cluster AA of beliefs, cluster NP of practices, and cluster NF of attitudes. In short, this is the cluster of the atheists/agnostics, who do not believe and do not practise at all, and hold contrary opinions to Church’s rules and trust a little or nothing in this institution.

This typology meets the ones from Lambert (1992), Lambert et al. (1997) and Fulton (2000). Cluster NC corresponds to the ‘confessional Christians’ or ‘nuclear Catholics’, believers in a personal God; cluster IC corresponds to the ‘cultural Christians’ or ‘intermediate Catholics’, who believe in an impersonal God; cluster Non-C corresponds to the ‘secular humanists’ or the ‘apostates’, non-believers. In this study the percentage of the most Catholics is approximately equal or higher than in the studies of Campiche et al. (1997) and Imaz (2004), whilst the percentage of atheists/agnostics is clearly higher and the percentage of the least Catholics is sharply lower.

And which are the dimensions and variables of religiosity to be included? From this study, attitudes seem to be less important for clustering religiosity. Rinaman et al. (2009) in their study about American Catholic religiosity highlighted seventeen variables, which they considered the most important to predict cluster membership. From these variables, ‘Representations about Jesus’ (resurrection), ‘Belief in life after death’, ‘Mass’, ‘Prayer’ (devotions to Mary), ‘Confession’, ‘Same-sex marriage’ and ‘Homosexual relations’ (homosexual behaviour) are common to my study. From the less important variables for Rinaman et al. (2009), only representations of Mary, abortion, and euthanasia were used in both studies.

For the second goal of this analysis, I begin with socialisation and its influence on clusters. Family religiosity gradually decreases from cluster NC to cluster Non-C.[8] The results show that the most religious young people have more religious parents. The child, the adolescent, and the youngster grow within the family, and are influenced by their parents, who are physically and emotionally closer to them and who are role models through their example and words. Here, the transmission of religious beliefs, practices, and values serves the continuity of a lineage. However, this diffusion is reduced by individualisation, wherein the looseness of social bonds and family role is patent. In fact, Voas and Crockett (2005: 20-22) stated that the gap in religious socialisation has produced entire generations who are less active and less believing than the previous ones: the children of middle age generation in relation to their parents have half the probability of believing and belonging (neither believing nor belonging).

The Catholic practices in family are basically the same in clusters NC and IC, but quite lower in cluster Non-C.[9] Perhaps this shows that these practices, while important to tell apart Catholics from atheists/agnostics, are not sufficient to distinguish the higher or lower Catholic religiosity, because these practices might not imply any deep religiosity on behalf of their parents. However, looking separately at the practices, there is a decrease from cluster NC to cluster Non-C in all of them. In ‘Going together to Mass’ and ‘Subscribing religious magasines’, clusters IC and Non-C are closer; in ‘Celebrating Christmas/Easter religiously’ and ‘Keeping religious symbols at home’, clusters NC and IC are closer; ‘None’ is bigger in cluster Non-C. The first two categories imply deeper commitment to the Church and so parents’ religiosity and transmission of faith are stronger. The population of cluster NC comes from these families; the other two involve less parental devotion, although some religiosity is required; in this case, cluster Non-C is set aside.

Other agents of socialisation besides the family also influence students’ religious position. These include ‘Church’, ‘school’, ‘friends’, and ‘cultural media’. The influence of family, Church, and school diminishes from cluster NC to cluster IC and the influence of friends is bigger in cluster NC than in the other clusters.[10] These results show that family, Church, school, and friends are determinant in religious socialisation. I have already alluded to the importance of family. The other entities also foster the religiosity in undergraduate students: the Church, with the examples and words of its priests, friars, and catechists; the schools, with their teachers’ instruction and possible testimony; the close friends with the likely capacity to mutually stimulate certain type of religiosity.

The Sunday school frequency diminishes from cluster NC to cluster Non-C [11] and conditions respondents’ religiosity. More religious education probably diminishes the possibility of being influenced by other doctrines and being conducted to other religions, beliefs, or philosophies. The Catholic school frequency decreases from cluster NC to cluster Non-C, although clusters IC and Non-C have close values.[12] Enrolment in Catholic schools differentiates more clearly cluster NC from the rest, a datum that may show a marked influence from Catholic schools on students’ identity. The presence in a Catholic environment disentangles them from the public school’s students.

In terms of closest friends’ religious position, there are clearly ‘more practising Catholics’ in cluster NC than in the other clusters. There are more ‘non-practising Catholics’ in cluster IC than in the other clusters. The ‘atheists/agnostics’ are sharply more present in cluster Non-C.[13] Having friends with religious affinities may help to develop and to strengthen one’s own Catholicism. Belonging to similar social contexts, with identical cultural capitals and experiences, induces proximate religious positions.

For all the parameters of Catholic religiosity transmission, cluster NC has always the highest values, followed by cluster IC.[14] This cluster approaches cluster NC only in ‘Baptising’, while in the others is nearer cluster Non-C. The mere fact of baptism does not implicate very high religiosity from the parents, whereas the others reflect bigger parental involvement in their children’s religious socialisation. In alternative ‘none’ almost 50% of cluster Non-C opted by this response, being null for cluster NC. Other important aspect is the inexistence of non-response in cluster NC, whilst in cluster IC and Non-C it was 10% and 13% respectively.

Non-Catholic beliefs are more common in cluster IC and less common in cluster NC, except for re-incarnation which is equal in clusters NC and IC.[15] Non-responses were more common in clusters NC and/or IC, depending on the belief, which may indicate that non-Catholics are more convinced of these beliefs. The existence of two extreme clusters (NC and Non-C), with stronger and clearer convictions, discourages the entrance of new beliefs in the personal ‘mixed kit’. On the contrary, in the less convinced, less consolidated religious territories, there is more space for the flexibility or plasticity of beliefs. Here the theory of religious patchwork or bricolage fits well. The permanence of spirituality in the individual and the religious institutions’ loss of influence open the possibility to obtain suitable beliefs for the consumer’s profile. Cluster IC is composed by people from lower social classes, followed by cluster Non-C; cluster NC has more people from higher social classes. So, these beliefs are far more common in people from not so privileged social classes, and thus likely less educated, and lower in students from higher social classes, probably more educated. Yet, there is an exception: the belief in re-incarnation is stronger in cluster NC than in cluster Non-C, possibly because it implies a belief in the sacred, a belief that is opposed to atheists/agnostics’ ideas.

All non-Catholic practices present very low frequencies, except meditation.[16] These results are supported by what Heelas and Woodhead (2005: 127) argued: “during the last few decades the milieu [in which can be included the non-Catholic practices] does not seem to have attracted many younger people”. In horoscope reading, frequencies are more differentiated and show cluster IC standing out for having higher percentages in more regular frequencies and lower in ‘never’.[17] As mentioned, the lack of conviction of cluster IC, together with a less educated background, creates conditions conducive to greater acceptance of heterodox practices, acquired in the profane or religious markets.

Finally, the students were asked about the importance of twenty-three aspects of life. These are important to understand not only the most central players in youngsters’ lives (e.g. family, friends), but also their Ersatz cults (e.g. music, sex, body). I wanted to comprehend what moves these young people, their passions, and so eventually what detaches them from Catholicism, partly or fully. Cluster NC stands out for ‘family’, ‘friends’, ‘religion’, ‘community organisations’, ‘love’, and ‘mobile phone’; cluster IC stands out for ‘professional success’, ‘academic success’, ‘health’, ‘TV’, ‘football’, and ‘big money’; cluster Non-C stands out for ‘politics’, ‘sex’, ‘internet’, ‘music’, ‘ecology/environment’; both clusters IC and Non-C stand out for ‘leisure’, ‘partying’, ‘sports’, ‘food’, ‘shopping’, and ‘beautiful/elegant body’. Still, from these aspects only four presented significant differences: ‘politics’ and ‘sex’, which increase from cluster NC to cluster Non-C; ‘religion’, which decreases from cluster NC to cluster Non-C; ‘academic success’, which is bigger in cluster IC.[18] These indicators, conjugated with non-Catholic elements, help to reformulate and deepen the original clustering, in order to measure the impact of individualisation. So, clusters can be characterised as follows:

Cluster ‘Nuclear Catholics’ ascribes greater importance to religion and to strong and lasting social relationships, whereby family, friends, community organisations, love, and mobile phone are relevant. Sex, as opposed to love, strikes lowest in this cluster. In fact, when regarded in a matter-of-fact light, sexual relations are insufficient to develop long lasting human relationships. This cluster appears more oriented towards the others, rather than self-oriented: its members want to help the others and to leave their mark, but more centred in the construction of relationship, of community. They do not want a radical upturning of the world; they appear more realistic than idealistic and search for concrete solutions. Here, the sacred is well defined, institutionally delimited, with a visible organisation, a set of beliefs, practices, and values to which this cluster faithfully adhere. On account of their orthodoxy and their more educated background, this cluster is less prone to accepting other cults or substitutes of religion. In short, this is the cluster of the socio-centred orthodox. Cluster ‘Intermediate Catholics’ ascribes great importance to success, both professional and academic. Cluster IC has a project centred in the individual rather in the others. Sports and welfare are also important, though less than success. This cluster contains, along with its Catholic heterodoxy and its lower cultural capital, the possibility of adopting other cults to the immanent sacred like success, which includes work, study, money, and beautiful/elegant body, to which can be associated sports and welfare (health and healthy food). In short, this is the cluster of the ambitious heterodox. Cluster ‘Non-Catholics’ gives importance mainly to sex and politics, which remain its new sacred, as here transcendent gods do not exist. Politics may be understood as revolutionary way of expression, channel of youthful energy and means of solving public problems. Concern for ecology/environment, likewise a new cult, can be lumped together with politics. Students in cluster Non-C also enjoy entertainment (internet, music, shopping, leisure, partying). Being the biggest, cluster Non-C congregates inside different trends. First, there are people centred in entertainment and sex; second, there are the mostly female political activists, who do not appear inclined to sex; third, there are those, mostly male, who combine politics with sex. In short, this is the cluster of the activist and hedonist non-believers.

Conclusion

In this study, I had two main goals: first, to group undergraduates by religiosity; second, to characterise them in terms of non-Catholic beliefs and practices, aspects of life, and socialisation. In short, I pretended to test secularisation, individualisation, and socialisation theories. In fact, this study had three main outputs. First, it confirmed the classification of previous researches. Second, it showed that secularisation, individualisation, and socialisation are not equal but vary with the segment of undergraduate population. Third, for me the most important output, it produced a new insight over the often studied clustering. The introduction of non-Catholic elements and aspects of life in the clusters turned them richer and fuller.

The sample is divided by one-fourth of nuclear Catholics, one-fifth of intermediate Catholics and more than a half of non-Catholics. The nuclear Catholics are those who have the strongest belief, who practise more and those who follow more closely Church’s rules. The non-Catholics do not believe, do not practise, and do not follow Church’s rules. The intermediate Catholics lay in-between these two. Interpreting the three clusters with the help of non-Catholic elements and aspects of life, they are reformulated: the nuclear Catholics become socio-centred orthodox, focused on religion and on people; the intermediate Catholics turn into ambitious heterodox, self-oriented, centred on success and more opened to alternative beliefs and practices; the non-Catholics are converted into activist and hedonist non-believers, centred on sex and politics. Generally, the religious socialisation of these clusters decreases from cluster NC to cluster Non-C. The impact of family, Church, school, and friends in students’ religious position decreases from cluster NC to cluster Non-C, although it is stronger in the first two. The close friends are chosen among those who have similar religious positions: NC with practising Catholics, IC with non-practising Catholics and Non-C with atheists/agnostics. The parameters about Catholic religiosity transmission confirmed what was expected, namely that the most religious families would spread their faith more than the least religious. Non-Catholic beliefs are stronger in cluster IC followed by cluster Non-C, with the already-mentioned single exception of re-incarnation. Of the non-Catholic practices, only one stands out from the others: horoscope reading. Once again, cluster IC distinguishes itself. The prevalence of horoscope reading signifies that this cluster is more open to the patchwork of beliefs and practices. Better educated families, from upper classes and from higher school education levels, divide in two: Catholic and non-Catholic convictions, although higher social class families are more represented in cluster NC. The cluster IC, less educated, has fewer profound convictions and is more receptive to alternative ideas: it can be moulded with beliefs, practices, and values from diverse origins, whereby individualisation assumption fits better this cluster. But is the minor level of cultural and financial capital enough reason to be more plastic, more unlocked to individualisation? Maybe the types of non-Catholic beliefs and practices influence the level of individualisation. In upcoming researches this topic could be developed with greater depth and extent: first, to identify the most important non-Catholic beliefs and practices for youngsters; second, to check the relationship between them and the clusters of religiosity; third; to understand the connection between social class and cultural capital in their choice.

References

Berger, Peter L. (1990 [1967]), Sacred Canopy. Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion, New York, Anchor Books.

Berger, Peter L. (2008), “Secularization falsified”, First Things. A Monthly Journal of Religion & Public Life, 180, pp. 23-27. [ Links ]

Berger, Peter L., et al. (2010), Religious America, Secular Europe? A Theme and Variations, Farnham, Ashgate. [ Links ]

Blasco, Pedro G. (2004), “La socialización religiosa de los jóvenes”, in Juan González-Anleo (dir.), Jóvenes 2000 y Religión, Madrid, Ediciones Santa Maria, pp. 119-165. [ Links ]

Blasco, Pedro G. (dir.) (2006), Jóvenes Españoles 2005, Madrid, Fundación Santa Maria. [ Links ]

Bruce, Steve (1992), Religion and Modernization. Sociologists and Historians Debate the Secularization Thesis, Oxford, Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Bruce, Steve (2011), Secularization. In Defence of an Unfashionable Theory, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Campiche, Roland (dir.) (1997), “Identité religieuse des jeunes en Europe: état des lieux”, in Roland Campiche (dir.), Cultures Jeunes et Religions en Europe, Paris, Editions du Cerf, pp. 45-96. [ Links ]

Casanova, José L. (2003a), “Círculos de pertença”, in João F. Almeida, et al., Diversidade na Universidade. Um Inquérito aos Estudantes de Licenciatura, Oeiras, Celta Editora, pp. 167-179. [ Links ]

Casanova, José L. (2003b), “Contextos de opinião”, in João F. Almeida, et al., Diversidade na Universidade. Um Inquérito aos Estudantes de Licenciatura, Oeiras, Celta Editora, pp. 181-193. [ Links ]

Cerezo, Jose, and Pedro Serrano (2006), Jóvenes e Iglesia. Caminos para el Reencuentro, Madrid, PPC Editorial. [ Links ]

Chaves, Mark (1994), “Secularization as declining religious authority”, Social Forces, 72 (3), pp. 749-774. [ Links ]

Codes — Gabinete de Estudos e Projectos de Desenvolvimento Sócio-Económico (1967), Situação e Opinião dos Universitários, Lisbon, Codes. [ Links ]

Cornwall, Marie, et al. (1986), “The dimensions of religiosity: a conceptual model with an empirical test”, Review of Religious Research, 27 (3), pp. 226-244. [ Links ]

Davie, Grace (2006), “Religion in Europe in the 21st century: the factors to take into account”, European Journal of Sociology, 47 (2), pp. 271-296. [ Links ]

Dobbelaere, Karel (1999), “Towards an integrated perspective of the processes related to the descriptive concept of secularization”, Sociology of Religion, 60 (3), pp. 229-247. [ Links ]

Eisenstadt, Shmuel (2000), “Multilple modernities”, Daedalus, 129 (1), pp. 1-29. [ Links ]

EVS (2010a), European Values Study 1990 Integrated Dataset. GESIS Data Archive, (release 2, 2007), 2nd wave, Cologne, Germany, ZA4460 Data File Version 2.0.0 (2010-04-13), doi: 10.4232/1.4460. [ Links ]

EVS (2010b), European Values Study 2008 Integrated Dataset. GESIS Data Archive, 4th wave, Cologne, Germany, ZA4800 Data File Version 2.0.0 (2010-11-30), doi: 10.4232/1.10188. [ Links ]

Fernandes, António T. (coord.) (2001), Estudantes do Ensino Superior no Porto. Representações e Práticas Culturais, Porto, Edições Afrontamento. [ Links ]

Fichter, Joseph H. (1969), “Sociological measurement of religiosity”, Review of Religious Research, 10 (3), pp. 169-177. [ Links ]

Figueiredo, Eurico, et al. (1987), Portugal, os Próximos 20 anos, vol. II: Conflito de Gerações, Conflito de Valores, Lisbon, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. [ Links ]

Figueiredo, Eurico, et al. (2001), Valores e Gerações. Anos 80 Anos 90, Lisbon, ISPA. [ Links ]

Fulton, John (2000), “Young adults, contemporary society and Catholicism”, in John Fulton, et al., Young Catholics at the New Millennium. The Religion and Morality of Young Adults in Western Countries, Dublin, University College Dublin Press, pp. 1-26. [ Links ]

Glock, Charles, and Rodney Stark (1969), Religion and Society in Tension, Chicago, IL, Rand McNally. [ Links ]

González-Anleo, Juan (2004a), “La religiosidad de los jóvenes: creencias, ritos y comunidad”, in Juan González-Anleo (dir), Jóvenes 2000 y Religión, Madrid, Ediciones Santa Maria, pp. 15-117. [ Links ]

González-Anleo, Juan (dir.) (2004b), Jóvenes 2000 y Religión, Madrid, Ediciones Santa Maria. [ Links ]

González-Anleo, Juan, and Juan María González-Anleo (2008), Para Comprender la Juventud Actual, Estella (Navarra), Editorial Verbo Divino. [ Links ]

Halman, Loek (2003), “Capital social na Europa contemporânea”, in Jorge Vala, et al. (orgs.), Valores Sociais. Mudanças e Contrastes em Portugal e na Europa, Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais, pp. 257-292. [ Links ]

Heelas, Paul, and Linda Woodhead (2005), The Spiritual Revolution. Why Religion is Giving Way to Spirituality, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Hervieu-Léger, Danièle (1998), “The transmission and formation of socioreligious identities in modernity: an analytical essay on the trajectories of identification”, International Sociology, 13 (2), pp. 213-228. [ Links ]

Hervieu-Léger, Danièle (2005), O Peregrino e o Convertido. A Religião em Movimento, Lisbon, Gradiva. [ Links ]

Imaz, Javier E. (2004), “Una tipología sociorreligiosa de los jóvenes españoles”, in Juan González-Anleo (dir.), Jóvenes 2000 y Religión, Madrid, Ediciones Santa Maria, pp. 167-192. [ Links ]

INE — Instituto Nacional de Estatística (1996), Censos 1991. Resultados Definitivos. Portugal, Lisbon, INE. [ Links ]

INE — Instituto Nacional de Estatística (2012), Censos 2011. Resultados Definitivos. Portugal, Lisbon, INE. [ Links ]

Lambert, Yves (1992), “Les jeux de la transcendance et de l’immanence”, in Yves Lambert, and Guy Michelat (dirs.), Crépuscule des Religions chez les Jeunes? Jeunes et Religions en France, Paris, Editions L’Harmattan, pp. 189-203. [ Links ]

Lambert, Yves (dir.) (1997), “Les croyances des jeunes européens”, in Roland Campiche (dir.), Cultures Jeunes et Religions en Europe, Paris, Editions du Cerf, pp. 97-166. [ Links ]

Lambert, Yves (1999), “Religion in modernity as a new axial age: secularization or new religious forms?”, Sociology of Religion, 60 (3), pp. 303-333. [ Links ]

Le Bras, Gabriel (1931), “Introduction à l’enquête de la pratique et de la vitalité religieuse du catholicisme en France”, Revue d’Historie de l’Eglise de France, XVII, pp. 425-449. [ Links ]

Maroco, João (2010), Análise Estatística — com Utilização do SPSS, Lisbon, Edições Sílabo. [ Links ]

Martin, David (1965), “Towards eliminating the concept of secularisation”, in Julius Gould (ed.), Penguin Survey of the Social Sciences, London, Penguin, pp. 169-182. [ Links ]

Martin, David (2005), On Secularization. Towards a Revised General Theory, Aldershot, Ashgate. [ Links ]

Martin, David (2011), The Future of Christianity. Reflections on Violence and Democracy, Religion and Secularization, Farnham, Ashgate. [ Links ]

Mauritti, Rosário (2002), “Padrões de vida dos estudantes universitários nos processos de transição para a vida adulta”, Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas, 39, pp. 85-116. [ Links ]

Mauritti, Rosário (2003), “Caracterização e origens sociais”, in João F. de Almeida, et al., Diversidade na Universidade. Um Inquérito aos Estudantes de Licenciatura, Oeiras, Celta Editora, pp. 13-30. [ Links ]

Pérez-Delgado, Esteban (2006), Impacto de la Religión en el Pensamiento de los Jóvenes. El Punto de Vista Psicológico y Otros Puntos de Vista, Salamanca, Editorial San Esteban. [ Links ]

Reis, Elizabeth, and Raul Moreira (1993), Pesquisa de Mercados, Lisbon, Edições Sílabo. [ Links ]

Rinaman, William C., et al. (2009), “Dimensions of religiosity among American Catholics: measurement and validation”, Review of Religious Research, 50 (4), pp. 413-440. [ Links ]

Scott, John (1997), Sociological Theory. Contemporary Debates, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar Publishing. [ Links ]

Silva, Manuel C., and José M. Monteiro (2000), “Estilos de vida numa concepção multidimensional de classe: o caso dos estudantes do politécnico de Viana do Castelo”, Cadernos do Noroeste, 13 (29), pp. 7-50. [ Links ]

Taylor, Charles (1991), The Ethics of Authenticity, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Taylor, Charles (1995), “Two theories of modernity”, Hastings Center Report, 25 (2), pp. 24-33. [ Links ]

Tschannen, Oliver (1992), “La genèse de l’approche moderne de la sécularisation : une analyse en histoire de la sociologie”, Social Compass, 39 (2), pp. 291-308. [ Links ]

Voas, David, and Alasdair Crockett (2005), “Religion in Britain: neither believing nor belonging”, Sociology, 39 (1), pp. 11-28. [ Links ]

Willaime, Jean-Paul (2006), “La sécularisation: une exception européenne? Retour sur un concept et sa discussion en sociologie des religions”, Revue Française de Sociologie, 47 (4), pp. 755-783. [ Links ]

Receção: 26 de novembro de 2012. Aprovação: 10 de janeiro de 2014

Notes

[1] However, two aspects have to be noted: first, non-answers decreased from 17.6% to 8.3%; second, in 1991 and 2011 the population with at least 12 or 15 years old respectively is considered. People with other religions passed from 1.8% to 3.8%.

[2] Since there are several age groups, only the youngest (15-24) and the oldest (> 64) groups are referred. All the results are weighted and are for 1990 and 2008. For indicator of practice (religious services attendance) only category ‘at least once a week’ is referred: 15-24 (26%/16%); > 64 (55%/41%). For indicators of attitudes the sum of categories from ‘never’ until ‘5’ is referred. Homosexuality: 15-24 (87%/65%); > 64 (96%/88%). Abortion: 15-24 (72%/61%); > 64 (87%/80%). Divorce: 15-24 (50%/42%); > 64 (71%/59%). Euthanasia: 15-24 (77%/61%); > 64 (89%/72%).

[3] Personal God: 15-24 (46%/58%); > 64 (80%/75%). Life after death: 15-24 (29%/50%); > 64 (62%/50%). Hell: 15-24 — (17%/40%); > 64 (50%/49%). Heaven: 15-24 (39%/47%); > 64 (79%/63%). Sin: 15-24 (52%/63%); > 64 (81%/78%). For the indicator ‘importance of religion’ the sum of categories ‘very’ and ‘quite’ is referred: 15-24 (39%/51%); > 64 (84%/77%). For the indicator ‘importance of God’ the sum of categories from ‘6’ until ‘very’ is referred: 15-24 (50%/60%); > 64 (87%/75%).

[4] Source: Bureau for Planning, Strategy, Evaluation, and International Relations — Ministry of Science, Technology, and Higher Education.

[5] According to Reis and Moreira (1993: 153-156), for a finite population the sample dimension can be calculated through the formula: n = S2 / [D2/(Z/2 )2 + S2/N] and the level of precision is equal to: ±D=±Z/2 S/[5]n = ± 4.4%— Z: normal distribution value (Z/2 = Z0.025 = 1.96), the confidence level is ( =1— = 1— 0.05 = 0.95); S: sample standard deviation (0.5); n: sample dimension (500).

[6] Cronbach’s Alpha has to be greater than 0.5; from 0.5 to 0.9, reliability varies between low and moderate; when greater than 0.9, reliability is high.

[7] Dimension 1: clusters of beliefs (0.682), clusters of practices (0.761), clusters of attitudes (0.513), inertia (0.652), Cronbach’s Alpha (0.734). Dimension 2: clusters of beliefs (0.591), clusters of practices (0.478), clusters of attitudes (0.358), inertia (0.476), Cronbach’s Alpha (0.449).

[8] Means: cluster NC (4.05), cluster IC (3.37), and cluster Non-C (2.74). 2 (4) = 85.758, p = 0.000.

[9] Percentages: clusterNC(95%), cluster IC (93%), and clusterNon-C(61%). 2(2) = 65.908, p = 0.000.

[10] Means: cluster NC (family — 4.0, Church — 4.0, school — 2.2, friends — 2.7, cultural media — 2.1), cluster IC (family — 3.4, Church — 2.8, school — 1.9, friends — 1.9, cultural media — 1.9), and cluster Non-C (family — 2.7, Church — 1.9, school — 1.6, friends — 1.8, cultural media—1.8). Family: 2 (4) = 56.796, p = 0.000; Church: 2 (4) = 127.930, p = 0.000; School: 2 (4) = 20.079, p = 0.000; Friends: 2 (4) = 42.027, p = 0.000; Cultural media: 2 (4) = 7.745, p = 0.101.

[11] Percentages: clusterNC(90%), cluster IC (78%), and clusterNon-C(53%). 2 (2) = 45.625, p = 0.000.

[12] Percentages: clusterNC(43%), cluster IC (28%), and clusterNon-C(22%). 2 (2) = 12.373, p = 0.002.

[13] Percentages: cluster NC (practising Catholic—56%, non-practising Catholic—64%, other religion—10%, atheist/agnostic—31%), cluster IC (practising Catholic—22%, non-practising Catholic—80%, other religion—4%, atheist/agnostic—39%), cluster Non-C (practising Catholic — 18%, non-prasticing Catholic — 67%, other religion — 4%, atheist/agnostic — 54%). x2 (8) = 67.989, p = 0.000.

[14] Percentages: cluster NC (baptizing — 95%, Sunday school — 85%, religious education — 85%, Catholic school — 27%, none — 0%, DK/NA — 0%), cluster IC (baptizing —72%, Sunday school 39%, religious education — 31%, Catholic school — 8%, none — 11%, DK/NA — 10%), cluster Non-C (baptizing — 29%, Sunday school — 12%, religious education — 11%, Catholic school — 6%, none — 49%, DK/NA — 13%). x2 (12) = 548.571, p = 0.000.

[15] Percentages: cluster NC (re-incarnation — 20%, luck/destiny — 35%, superstitions — 13%, efficacy of magic — 7%), cluster IC (re-incarnation — 26%, luck/destiny — 74%, superstitions — 40%, efficacy of magic—24%), cluster Non-C (re-incarnation — 20%, luck/destiny — 54%, superstitions — 28%, efficacy of magic — 18%). Re-incarnation: x2 (2) = 5.604, p = 0.061; Luck/Destiny: x2 (2) = 29.808, p = 0.000; Superstitions: x2 (2) = 17.363, p=0.000; Efficacy of magic: x2 (2) = 10.710, p=0.005.

[16] Percentages of frequency ‘never’: cluster NC (yoga — 93%, reiki — 100%, meditation — 75%, seer consultancy — 98%, feng shui — 97%, spiritism — 100%, tarot — 97%), cluster IC (yoga — 92%, reiki — 96%, meditation — 76%, seer consultancy — 92%, feng shui — 96%, spiritism — 96%, tarot — 87%), cluster Non-C (yoga — 86%, reiki — 95%, meditation — 78%, seer consultancy — 96%, feng shui — 95%, spiritism — 96%, tarot — 93%). Yoga: Phi = 0.111, p = 0.187; Reiki: Phi = 0.083, p = 0.499; Meditation: x2 (4) = 0.432, p = 0.980; Seer consultancy: Phi = 0.107, p = 0.219; Feng Shui: Phi = 0.083, p = 0.493; Spiritism: Phi = 0.071, p = 0.648; Tarot: Phi = 0.112, p = 0.191.

[17] Percentages: cluster NC (weekly/monthly — 18%, annually/less often — 27%, never — 55%), cluster IC (weekly/monthly — 34%, annually/less often — 29%, never — 37%), cluster Non-C (weekly/monthly — 23%, annually/less often — 25%, never — 52%). x2 (4) = 10.789, p = 0.029.

[18] Means: cluster NC (politics — 2.7, religion — 4.2, academic success — 4.4, sex — 3.4), cluster IC (politics — 2.7, religion — 2.6, academic success — 4.5, sex — 3.8), cluster Non-C (politics — 3.0, religion — 1.8, academic success — 4.4, sex — 4.1). Politics: x2 (4) = 8.793, p=0.066; Religion: x2 (4) = 290.361, p=0.000; Academic success: Phi = 0.132, p=0.067; Sex: x2 (4) = 28.565, p=0.000.