Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas

versión impresa ISSN 0873-6529

Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas no.68 Oeiras ene. 2012

https://doi.org/10.7458/SPP201268697

Care: a challenge to healthy organizations? A case study of a hospital department

Leila Billquist*, Stefan Szücs**, and Margareta Bäck-Wiklund***

* Senior lecturer at the Department of Social Work, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. E-mail: Leila.Billquist@socwork.gu.se

** Assistant professor at the Department of Social Work, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. E-mail: Stefan.Szucs@socwork.gu.se

*** Emeritus professor of Social Work and Family Policy at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. E-mail: Margareta.Back-Wiklund@socwork.gu.se

Abstract

In this article we study a healthy organization through exploring the dual agenda from the perspective of a human service organization. Looking at the case of a specialized department at a major teaching hospital in Sweden, we analyze whether the concept of the healthy organization needs an added dimension. Quantitative and qualitative methods have been used, collected within the framework of the EU project Quality of Life in a Changing Europe. We explore the dual agenda from two perspectives the work-household duality and workforce-organization duality. Using a multi-method approach shows a complex picture, especially with regard to stress and workload intensity.

Keywords healthy organizations, human service organization, health care, multi-method approach, workload intensity.

Cuidado: um desafio para as organizações saudáveis? Estudo de caso de um serviço hospitalar

Resumo

Neste artigo estudamos uma organização saudável através da exploração da agenda dual, na perspetiva de uma organização de serviços a pessoas. Olhando para o caso de um departamento especializado num hospital universitário na Suécia, analisamos se o conceito de organização saudável necessita de uma dimensão adicional. Foram usados métodos quantitativos e qualitativos, recolhidos no âmbito do projeto europeu Qualidade de Vida numa Europa em Mudança. Explorámos a agenda dual em dois planos a dualidade do trabalho doméstico e a dualidade do trabalho em contexto organizacional. Usámos uma abordagem multi-método que dá a conhecer uma realidade complexa, especialmente no que diz respeito ao stress e à intensidade da carga de trabalho.

Palavras-chave organizações saudáveis, organização de serviços a pessoas, saúde, abordagem multi-método, intensidade da carga de trabalho.

Les soins: un défi pour les organisations saines? Une étude de cas d'un service hospitalier

Résumé

Cet article étudie une organisation saine à travers lexploration du double emploi du temps, du point de vue dune organisation de services à la personne. En observant le cas dun département spécialisé dans un hôpital universitaire en Suède, nous nous sommes demandé si le concept dorganisation saine nécessite une dimension additionnelle. Les méthodes quantitatives et qualitatives utilisées ont été relevées dans le cadre du projet européen Qualité de vie dans une Europe en changement. Nous avons exploré le double emploi du temps sur deux plans la dualité du travail domestique et la dualité du travail en milieu organisationnel. Nous avons utilisé une approche multi-méthode qui nous permet de connaître une réalité complexe, surtout en ce qui concerne le stress et lintensité de la charge de travail.

Mots-clés organisations saines, organisation de services aux personnes, santé, approche multi-méthode, intensité du volume de travail.

Cuidado: ¿un desafío para las organizaciones saludables? Estudio de caso de un servicio hospitalario

Resumen

En este artículo estudiamos una organización saludable a través de la exploración de la agenda dual, en la perspectiva de una organización de servicios a personas. Observando el caso de un departamento especializado en un hospital universitario en Suecia, analizamos si el concepto de organización saludable necesita de una dimensión adicional. Fueron utilizados métodos cuantitativos y cualitativos, recabados en el ámbito del proyecto europeo Calidad de Vida en una Europa en Cambio. Exploramos la agenda dual en dos planos la dualidad del trabajo doméstico y la dualidad del trabajo en contexto organizacional. Utilizamos un abordaje multi-método que da a conocer una realidad compleja, especialmente en relación al stress y a la intensidad de la carga de trabajo.

Palabras-clave organizaciones saludables, organización de servicios a personas, salud, abordaje multi-método, intensidad de la carga de trabajo.

Introduction

Today, when we study peoples well-being we include both work and family and the concept work-life balance; these have slightly different meanings depending on the context around the world. Both political and organizational programs have been worked out to promote the development of increased quality of work and life (Fleetwood, 2007). Studies of problems associated with working alongside other elements of life, especially family life, are nothing new. Working and quality of life, and the balance between them, have become central in both research and practice because of social, political and economic developments. All of this has meant a radical transformation in the nature of work (Bäck-Wiklund et al., 2011). The labour market has changed in response to rapid technological development, globalization and womens greater participation in the workforce. In light of all of these changes, it is more important than ever to study the dualities of work and personal life, as well as between employee and organizational needs. In this field of research the focus is often directed towards workplaces that meet the dual agenda of organizational efficiency and the need for support, motivation and encouragement of employees (Lewis et al., 2007). A relevant concept in this context which is increasingly found in the literature is that of healthy organizations (Lewis, 2008; Lewis et al., 2011).

From a European perspective, Swedish work-life arrangements emerge as both challenging and stressful. Swedish workers experience more work pressure than do other workers in Western Europe, especially in the health sector, where work intensity has increased (Houtman et al., 2006). The challenge to health-care employees and their organizations is to find ways to manage these changes as employee autonomy and control over workloads become more dependent on clients, patients, colleagues and managers. How does this challenge the healthy organization? Do these requirements meet the needs of human service organizations in which client/patient care and well-being are at the centre? Is the so-called dual agenda adequate, or do we need an additional dimension in order to speak of a healthy organization in relation to human service organizations and employees work-life balance?

Looking at the case of a specialized department at a major teaching hospital a human service organization we will discuss the above research questions. First, however, we will identify some characteristics that apply to these specific kinds of organizations.

Defining healthy organizations

Whether organizations can be described as healthy or unhealthy has been discussed since the early 1990s (Lewis, 2008). On a global level, there is a consensus that, in order to be healthy, organizations must be effective in both what they do and how they meet the needs of the workforce, as individuals and the organizations well-being are linked (Lewis et al., 2011). Thus, healthy organizations are those [ ] that recognize that the needs of employees and the organization are mutually interdependent, and that strive to meet the dual agenda of employee quality of life and organizational success and sustainability (id., ibid.: 166). According to this definition, the healthy organization is therefore a workplace that meets the dual agenda of achieving organizational efficiency and effectiveness and meeting employees needs for support, motivation and encouragement.

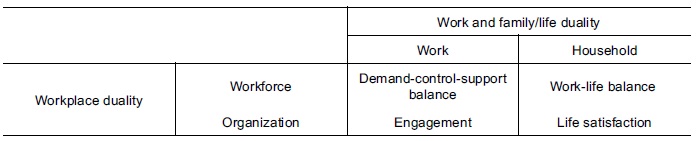

Nevertheless, a second type of dual agenda concerns the duality between work and personal or family life. Employees in a healthy organization need to be able to balance increased work demands by gaining more control over their work and by being given greater support, in line with the classical demand-support-control model (Karasek, 1979; Karasek and Theorell, 1990). Such employees are probably also characterized by a greater average level of satisfaction with the way they are able to balance their work and personal lives (Valcour, 2007; Szücs et al., 2011). Further, at the organizational level, the healthy organization as we define it needs to be both effective and sustainable. Hence, the healthy organization needs not only a workforce characterized by the ability to balance demand with control and support at work as well as work-life balance. In order to be healthy, the organization also needs a high level of engagement at work and sustainability in relation to the household domain, indicated by a high degree of life satisfaction. Thus, in our effort to define the healthy organization we need to look at the four different aspects of the dualities coming from the workplace and the household domains of life (figure 1).

Figure 1 The dual dimensions of the healthy organization

Drivers of healthy organizations: transparency from above, participation from below

Findings from previous studies in this field indicate that there are two distinct categories that foster healthy organizations: managerial leadership transparency and employee participation. First and foremost, several studies emphasize the importance of leadership and managerial transparency. Research trying to explain the correlation between reorganization and long-term sick leave among public sector employees in Sweden quite early on showed that this relationship was triggered by different kinds of managerial indistinctness (Szücs, 2004). The importance of leadership and managerial transparency in this respect has been verified in more recent large-scale studies in Sweden in both the public sector (Holmgren, 2008; Szücs and Hemström, 2010) and the private sector (Ahlberg et al., 2008). Cross-county comparative case studies of healthy organizations indicate the importance of managerial transparency, emphasizing the importance of equity, fairness and job security as well as the importance of defining specific working practices for creating and maintain the healthy organization (Lewis et al., 2011: 175-177).

Although managerial leadership transparency is probably necessary for the healthy organization, many times it is not enough; several studies have pointed at the importance of a second, participatory, aspect as well. The above-mentioned research on reorganization and long-term sick leave among public sector employees in Sweden further showed that long-term sick leave was also triggered by reorganizations that were carried without the participation of the employees (Szücs, 2004). More recent studies in Sweden on the characteristics of healthy organizations point not only at the importance of transparency from above, but also at the impact of participation from below in making the healthy organization work. These studies cover companies in both the public sector (Holmgren, 2008; Szücs and Hemström, 2010) and private sector (Ahlberg et al., 2008). Recent country comparative case studies have enhanced understanding of the driving forces behind the participation from below, by pinpointing important features such as opportunities for personal satisfaction and growth and good interpersonal relationships (Lewis et al., 2011: 176-177).

At the same time, when looking at human service organizations, we find that they are often characterized by various complexities that constrain both transparency and participation (Hasenfeld, 2010).

Human service organizations: characteristic features

Human service organizations are complex; they exist in various forms, with varying tasks and methods. They play a pivotal role in the lives of people. Individuals and families are highly dependent on them to enhance, maintain and protect their well-being (Hasenfeld, 2010: 9). They are organizations whose task is to assess and sort people and in different ways mitigate, cure or affect them, their behaviour and life circumstances. The work is inherently moral because these organizations work with people. People are their raw material. The work is not just about providing service to citizens but, to quote Hasenfeld (ibid.), confers a moral judgement about their social worth, the causation of their predicament, and the desired outcome. The organizations work rests on moral principles grounded in an ideology of greater prosperity. Human service organizations have attributes that emanate from this feature: the relation between clients and personnel where the quality of this relationship is important for the results of the work; dependence on the institutional environment, which has become more complex; an indeterminate service technology; and emotional and gendered work (the majority of the workers are women) (id., ibid.). Human service organizations are also characterized by goals that are vague and ambiguous. At the general policy level, the focus and the goals of the service are agreed upon, but on a practical, operational level, there are often variations and disagreements. They are multi-target organizations. They are also dependent on external conditions and are easily affected by peoples expectations. Their work is, in most cases, directed by the political system.

Discretion has become a central concept in the analysis of hierarchical human service organizations. The work in these organizations is performed in direct interaction with the patients and in complex situations that sometimes make it difficult to standardize the work. It requires the staff to be constantly alert and makes great demands on their capabilities and decision-making skills. Discretion in a limited sense means that professionals make assessments and diagnoses on their own, decide on treatment, or otherwise act within a given operational and regulatory structure of delegation (Lipsky, 2010).[1] Discretion is affected by many factors, not least workplace culture and how the professionals perceive their autonomy and control over their work. In this study we are mainly interested in how these kinds of complexities in human service organizations in the area of health care affect the healthy organization.

Design and methods

Our paper is based on the completed EU project titled Quality of Life in a Changing Europe, whose aims were to examine how, in an era of major change, European citizens living in different national welfare state regimes evaluate the quality of their lives.[2] Both quantitative methods (a survey) and qualitative methods (interviews and innovation groups) have been used. The project has analyzed international comparative data on the social well-being of citizens and collected new data on social quality in European workplaces in eight strategically selected partner countries: the United Kingdom, Finland, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, Hungary and Bulgaria (Bäck-Wiklund et al., 2011).

The sample of organizations included in the study was selected to cover a wide range of employees working in the service sector in the EU. Therefore, it was decided that organizations in the service sector that are often perceived as low to medium status, as well as high-status service organizations, should be included in the study. The goal was to include both supermarket employees and those employed at a high-ranking university hospital department. However, human service organizations do not only differ in workplace status, but also in terms of social relationships, especially in regard to whether they work in relation to customers, clients or patients. While some service organizations have material service relations (customers), other service organizations have personal service relationships with individual clients or patients. Data has been collected using a variety of methods, and it also covers different levels: the employee level, the employer level, the organizational level and the policy level (Van der Lippe et al., 2011).

The case study approach was used to get a better understanding of what a healthy and sustainable organization is and what factors influence this. The case study allows us to examine and deepen our understanding of complex phenomena and processes in a specific context (Lewis et al., 2006). Each country chose one of the previously studied organizations; the idea was that, wherever possible, the hospital would be chosen to ensure some comparability (see Lewis, 2008; Bäck-Wiklund et al., 2011). However this was not feasible in all the countries. The case study research was carried out in five hospitals (in Sweden, Finland, the United Kingdom, Bulgaria and Germany) and in three private sector organizations (in Portugal, the Netherlands and Hungary). The case studies were carried out in summer 2007 through interviews with staff at different levels in the selected workplaces and with innovation groups. A semi-structured interview guide, common to all countries, was prepared for the individual interviews. After an initial introduction and discussion of the concept of the dual agenda, the interviews followed a timeline past, present and future. The aim was to gain an understanding of how organizations change and the impact such changes may have on employees lives and work quality, and to enhance understanding of what characterizes a healthy organization, focusing particularly on the requirements within the sector. The interview process provided respondents with opportunities for reflection and free thinking. Analysis was undertaken to identify major themes relating to aspects of healthy organizations (see Van der Lippe et al., 2011: 70).

In this study we focus on a department in a specialized teaching hospital in Sweden, and on the part of the web survey addressed to this department. It is a large teaching hospital for training medical students. Close to the hospital is a large health care institution in which nurses and other care-giving staff are trained. As a high-quality teaching and research institution, the hospital is challenged to become a knowledge-driven centre among the leading international hospitals. Data from the survey and from the interviews and innovation group is compared.

The survey

The survey was conducted in four different human service sector organizations in bank/insurance, retail, IT/telecom and public hospital health care. The health care sector was selected to represent the part of the service sector that is a high-status publicly financed organization, in which employees largely work directly with the patients. In order to control for regional bias, all four organizations participating in the study were located in the Gothenburg area (Szücs et al., 2008). A web survey was sent to employees with questions about their work situation as well as their family and life situation in order to gain a better understanding of what affects quality of life, and also to predict how quality of life may be affected in the future, whether positively or negatively, both at work and outside of work. The questionnaire included questions about resources and requirements in the two spheres and had been adapted for use in all participating countries (7869 responses were received, 676 from Sweden).

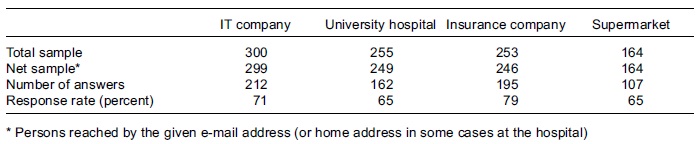

The sample of 300 employees at the IT company was selected randomly from a total of approximately 2700 employees. The other three samples consist of the entire population of employees at the supermarket, the insurance company, and the teaching hospital department. The response rate was highest at the insurance company (79 percent), followed by the IT company (71 percent) and the insurance company and the hospital (65 percent).

Table 1 Response rate at the four sampled organizations

The case study

The original intention of the project was to interview participants from a single department so that the second phase of the study (innovation groups) could focus in depth on specific issues (Van der Lippe et al., 2011). In Sweden, professional contacts led to the selection of one highly specialized department at the teaching hospital, which consists of five units, including three different wards, providing care for critically ill patients. Our contact at the hospital helped in the recruitment of participants. Ten members of the staff were interviewed, of whom eight were women, which is proportionate to the gender distribution of the entire hospital department. Nurses, assistant nurses, doctors and managers at various levels were among those interviewed. Four of them held or had held a managerial post. Among those interviewed were also representatives of trade unions that organize doctors, nurses and other medical staff (Lane et al., 2008b).

The innovation group was conducted after the individual interviews and was composed of the same group of staff who participated in the interviews and who represented different functions in the workplace. The purpose of the innovation group was to return the results of the individual interviews in order to start discussing the challenges that emerged from the analysis with regard to the healthy organizations dual agenda. In the innovation group there were four staff members, all women: two nurses, one of them a union representative and the other employed as research coordinator; an assistant nurse and an assistant manager. (A junior doctor cancelled the interview because of an emergency call.) The results of the survey and the case study were communicated to the participants in both written and oral form (id., ibid.).

The empirical setting

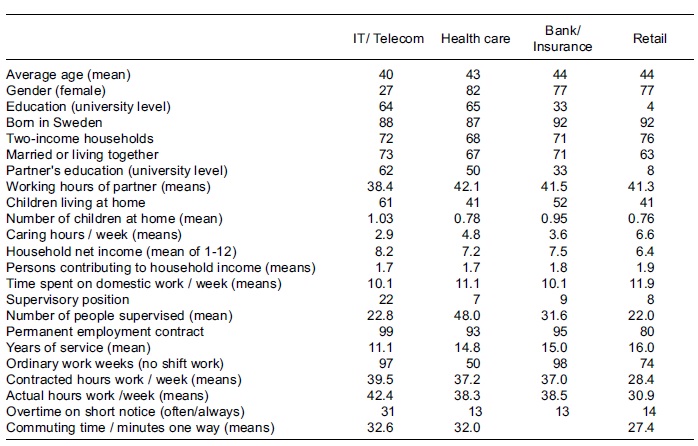

Table 2 shows that, among the Swedish sample of service sector organizations, the caring organization not only has the most female-dominated workforce, but also the most highly educated, with the largest number of people supervised per manager, and the highest proportion of shift work among the workforce (Szücs and Cliffordson, 2008). In terms of home-related background variables, we also find that the estimated time of the partners working hours per week is also the highest.

Table 2 Employee characteristics at the four sampled Swedish organizations (%)

Results

According to our definition, the concept of healthy organizations is about handling the dual agenda. In our model (figure 1) the intention is to view the dual agenda from two perspectives, thereby acknowledging both the work-household duality and workforce-organization duality.

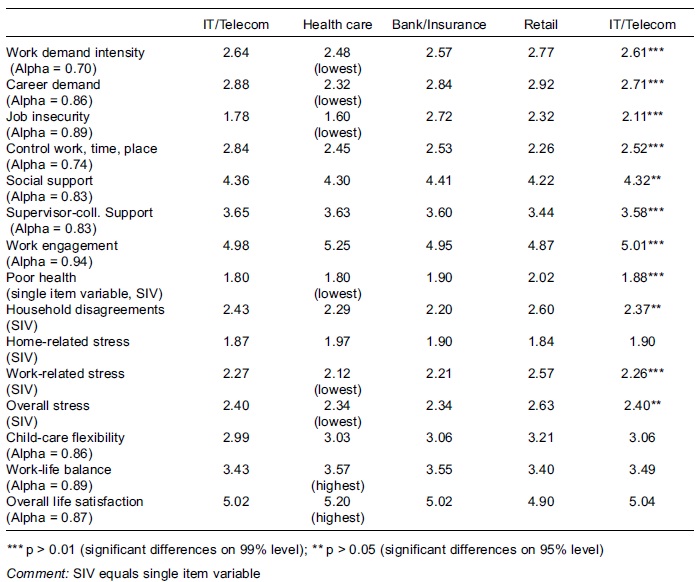

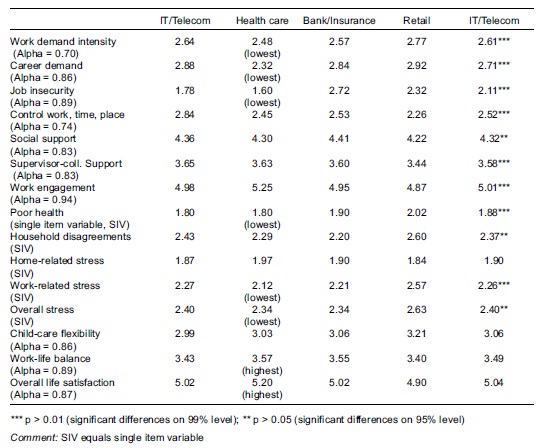

The healthiest organization according to the web survey

Looking more closely at the different job and household characteristics could lead us to conclusions about the degree to which caring work also represents the healthiest organization. The analysis shows that the teaching hospital department can be characterized as a healthy organization. It has, on average, the least stressed workforce paired with the highest level of organizational work engagement. In terms of characteristics related to personal and family life, it is equally healthy: on average, the perception of work-life balance, satisfaction with life, and subjective health are regarded as the highest in the caring organization (table 3). However, the workforce in the teaching hospital department does not have the greatest level of control over its work, and it does not receive the most support.

Table 3 Valid job and household characteristics at the four sampled Swedish organizations (Anova / means)

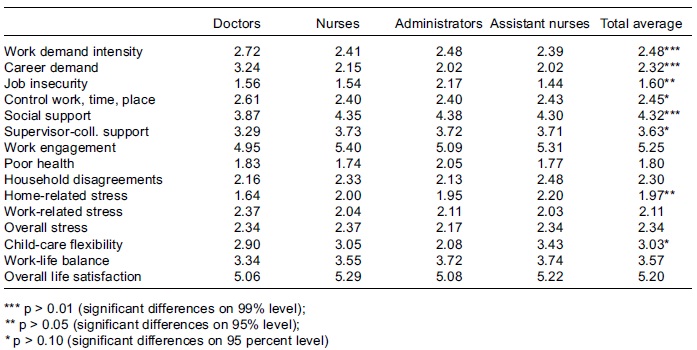

Occupational differences at the teaching hospital department

There are four main occupational groups of staff at the teaching hospital department: doctors, nurses, assistant nurses and administrators. As shown in table 4, female workers are in the majority regardless of occupational status. In general, both work-related and domestic characteristics are quite evenly distributed: there are small differences between doctors, nurses, administrators and assistant nurses when looking at the background characteristics of these different occupational groups at the teaching hospital department. Large discrepancies exist only in relation to having a supervisory position, number of staff supervised, actual work hours per week and overtime on short notice; these features are much more common among the doctors.

Table 4 Employee characteristics of the teaching hospital department (%)

Thus, considering these findings, it can be assumed that different kinds of strain can be found mostly among this category (doctors). Looking at the findings in table 5, we find that this assumption is at least partly correct. The doctor category is first and foremost characterized as having, on average, the highest work demand intensity, career demands and work-related stress (no statistically significant difference). Nevertheless, the doctors are able to balance these significantly higher demands by having, on average, the highest level of control over their work. Other types of strain, such as job insecurity are experienced more by the administrative staff.

Table 5 Valid job and household characteristics at the teaching hospital department (Anova / means)

A second set of statistically significant differences between the occupational groups of the staff include the social dimension of work. The highest levels of average social support as well as supervisor-colleague support are found among nurses, administrators and assistant nurses. The doctors generally receive much lower levels of social support and supervisor-colleague support. Thus, among the doctors, high average levels of strain (demand) are mainly compensated for by control over work rather than by social support. For the nurses, assistant nurses and administrative staff, on the other hand according to the demand-support-control model (Karasek, 1979; Karasek and Theorell, 1990) the prospects for achieving a healthy balance between demand, support and control seem to be somewhat greater.

Finally, a third set of statistically significant differences between the occupational groups include the household dimension. Here we find that home-related stress in particular is carried by the assistant nurses, even though they have the highest level of child-care flexibility. Thus, regardless of having the best reported conditions of handling child-care flexibility, their home-related stress is still reported as the highest. In particular, this finding seems to depend on the quite high levels of shift work. As shown in table 4, among the assistant nurses only 17 percent report that they have ordinary working hours with no shift work. The assistant nurses also have the highest percentage and number of children living at home, which gives further evidence of a household-related imbalance. The differences between the occupational groups at the hospital department concerning satisfaction with work-life balance and overall life satisfaction, nevertheless, are not statistically significant.

Qualitative data analysis: underlying dilemmas of the healthy organization

The hospital department is an organization with an elite staff that is controlled by politicians at the top level. Decisions taken at this level can sometimes be in opposition to the treatment-oriented goals. The hospital is just like other human service organizations that are sensitive to changes in the world, not least changes related to the economy (Hasenfeld, 2010). The hospitals operating budget is a recurring theme. In the implementation of the interviews the Swedish hospital was facing heavy financial cuts. Financial cutbacks for the whole hospital were announced, which affected all areas of expertise. Almost all the interviewees, regardless of level and position, were affected by the cuts and there was a fear that changes motivated by financial considerations would ultimately affect the quality of work.[3]

In the analysis of the interviews we have identified major themes with sub-categories. From the interviews we want to distinguish between the following key themes: (1) high engagement and demand; (2) communication transparency and participation; (3) stress the patient as first priority; and (4) balance between work life and family life.

High engagement and demand

All who participated in the interviews were very committed to their work, particularly the work they do with patients, and they perceived their work as meaningful. We interpret this in line with the high work engagement as expressed in the web survey. They also agreed that a healthy organization could meet the dual agenda, that is, it could be both an effective workplace and maintain a good working environment. But it was not always so in the actual situation and the dual agenda was not always as important to managers as to other employees. They did not always see the link between quality patient care and employee quality of life; to provide good care and have time for patients also gave personnel satisfaction. The interviewees expressed that [finance] threatens both personnel and patients and by extension jeopardizes the possibility to achieve the overarching goal for the work in the entire hospital. The financial situation constitutes a major obstacle to the implementation of the dual agenda and compromises patient care.

Positive factors identified in the department were employment security, predictable working hours, opportunities for self-development and training, and support from colleagues. The opportunities for development and upgrading skills were highly appreciated, and also seen as a must due to the rapid technological and medical developments that are underway. The interviewees were very satisfied with the hospital, which contributed to employees skills while providing opportunities for development, including opportunities to attend both internal and external training courses. All interviewees enjoyed their own workplace, especially their own small work unit the hospital as a whole was regarded as a colossus. The interviewees were also often satisfied with the support they got, especially the feedback from patients and their relatives, and with developments towards providing further support in the form of staff and workplace meetings and relief calls. The importance of good team spirit and social relationships was also stressed by all, and in some cases this compensated for a stressful work situation:

We have a pretty good commitment in the workplace, the workload is distributed in a fair way, we are close, cooperate and we have a lot of fun! However, it is a tough climate when you work you concentrate on that, and when you take a break in the coffee room you try not to talk about work [Assistant nurse, woman]

Good working colleagues makes most things bearable. [Nurse, woman]

The standard norm for the personnel is leading themes; high levels of knowledge and competency. The overall climate is open and even cheerful; however, the section has a reputation for being a tough place to work but the personnel cope. [Middle manager, woman]

Communication: transparency and participation

Cohesion, collegiality and information found in the interviews are important factors for a healthy organization, but these are related to ones own working group or closest colleagues, while information and communication between the different levels within the hospital organization functioned poorly. The personnel described the communication and information problems in three ways: (1) as parallel information tracks, whereby personnel at the same level were privy to different information concerning a common problem; (2) information overload; there was no shortage of information on the contrary, the personnel had too much information and they did not have enough time to process or sort out what was really relevant to their work; and (3) a need for better communication between different levels. This was a recurrent theme in the interviews, and it was articulated in different ways:

Better communication within the organization as such and above all between the political board and the hospital, i. e. more long-term planning, you need to take into account more than one year in advance. [Doctor, man]

The most important hindrance to creating a healthy organization is an unclear organizational structure where employees are unsure of their rights and duties. Where there is poor communication between the different levels. Where employees feel they are not heard and are constantly walked over. [Assistant nurse, woman]

As we can see, the lack of communication is interpreted in various ways and means different things depending on the position or function within the organization. The doctors with their greater responsibilities complain about political governance that can hinder them in their professional careers. The professionals at the lowest hierarchical level felt walked over. Thus, while the healthy organization is threatened by a lack of transparency from above, it is also dependent on participation from below.

Yet another example illustrating the importance of effective communication is the staffs experience when it comes to financial cuts. They are the last to be informed and sometimes it is done through newspaper articles. Here, you feel far away within the big organization the hospital as a whole with its political leadership.

The importance of a structured leadership at all levels of the organization and transparency of communication it must reach down to all to really be a healthy organization was highlighted, especially in the innovation group.

Stress: the patient as first priority

Stress was something highlighted by all interviewees, but it took different forms depending on job function and position in the organization. These are stresses related to the intensification, tempo, and physical demands of the work, as well as to patients:

Our staff experience stress in different ways. Different professional cultures meet in the care of patients, periods of increased workload may be aggravated by a lack of communication this can lead to conflicts that may be viewed as infringement of the professional role. [Hospital manager, man]

The challenges are positive and negative; positive in that it is fun to be a part of a new task. It is educational; one meets new people etc.; negative [in that there is] over-work, stressful work intensification; [ it] is stressful at the moment, [but] once the ward is complete and the routines are in place, the ward will be a good place to work in. [Nurse, woman]

Mentions of higher work intensity, a heavier workload and an increased work rate formed a pattern in the interview responses. Much was linked to the need to treat more patients in less time, but also to changing tasks and new job requirements to keep abreast of new technologies, new rules and procedures and, in some cases, increased reporting requirements and other aspects of the bureaucracy. All the interviewees experienced change in patients needs. Patients know their rights, and their threats to report on poor care or on staff not doing a good job increases stress levels among nursing staff. The new EU legislation regarding the regulation of working hours also caused stress and somewhat paradoxical consequences, as the following quotations illustrate:

It leads to more and shorter working periods. Some weeks you are supposed to work every second night during a three-day period a schedule with a week where you are on call during the night it becomes a burden to switch between day and night shift in such a short time but on the other hand it has also positive consequences as it gives you a period of four weeks when you are not on call. [ ] But the new rules have contributed to an increased work tempo. [Doctor, woman]

Instead of getting more personnel to help fill the schedule, the ward lost a staff member by reducing the changeover time between shifts! [Assistant nurse, woman]

The increased intensity of work meant that doctors and nurses had less time to provide patients with emotional support, and their work was largely limited to performing medical duties. The goal of both the hospital and the staff is to make patient well-being their first priority, yet this goal could be compromised and cause increased concern. Pressure on staff to do more in less time also meant increased fear of making mistakes; patients and personnel must feel safe in the wards. The staff that meets the patients expressed feelings of inadequacy and of not being able to perform top-quality work. According to one of the interviewed nurses, the major problem is the lack of time lack of time for patients and lack of time for personnel.

Dealing with economic issues in ways that may undermine the employees well-being and give rise to fears that the cuts will affect and impair patient care raises serious concerns. The economic situation also affects the medical equipment, again something that can ultimately impair patient care and working conditions. Participants in the study reported that it felt stressful to not have sufficient space to accommodate modern medical equipment necessary for good health care some of the new machines are placed in rooms that are not dimensioned for them. When space is inadequate, the work is experienced as physically demanding.

Most stress was expressed by those groups that had less control over how their work was distributed, including doctors, nurses and assistant nurses, whose planning and daily schedules can be overtaken by emergencies. But administrative staff as well, including managers and supervisors at various levels, reported increased workloads. Managers tend to spend more time on planning to fulfil the departments tasks within the given budget:

This is a double-edged sword; our staff gain a great deal of professional satisfaction from the care they give our patients; on the other hand, they must reconcile themselves to the fact that no matter what their personal feelings they cannot shirk their responsibility to deliver care, as the needs of the patients always take first priority. [Hospital manager, man]

To sum up, in an organization in which change is a normal condition, where increased work tempo and work intensification permeate the workday, as does organizational change generated in the overarching hospital organization and reorganization planning and logistics become particularly important. This finding relates to the cross-national comparison, where it was concluded that, under the present circumstances of such sharp increases in work intensity, maintaining a sustainable and healthy organization is not possible; this has been said by all of the interviewees from hospitals in five countries (Lewis et al., 2008).

Balance between work life and family life

The above-mentioned themes affect the interviewees work-life balance in different ways. When talking about work-life balance, the flexibility of working is often mentioned as an important criterion, and also something that is central to improving gender equality. Flexible working hours or a rotating work schedule may be experienced as stressful by employees who do not have control over their working hours. Some felt they had little control, but once they were off work, the job seldom interfered with their private lives.

A very important aspect of my work that makes my life easier and allows me to go home and not worry about the job is that I know I can trust my colleagues to do a good job and they know they can trust me. When I go home I know I am leaving our patients in good hands. [Nurse, woman]

How working hours and work schedules affect family life and leisure time was dependent on the interviewees position and function in the organization. Staff in high positions devote much time to their work and find it difficult to draw a line between work and family. They take home more and more work and are always on call. [ ] You are a manager both day and night [former manager, man]. They need more support in the organization than they receive today. My support, I get [at] home [middle manager, woman].

The real impingement on leisure time is fatigue, both mental and physical resulting from increased work tempo and work intensification. More leisure time needs to be scheduled in order to allow staff to recover adequately between shifts. The opportunity to talk about strong emotional experiences was of great importance in enabling employees to relax at home and not worry about the job, but this was not possible for everyone when they were working on schedule.

Future challenges: some reflections

The interviewees felt that stress would continue to be a major factor in their work. The staff must be prepared to change workplace, work with different occupational groups and perform different tasks throughout their work lives. New therapies and changing technologies will be developed which lead to the need for continuous professional development, and lifelong learning will be an integral part of their professional lives. All agreed that another important task for the future was to improve communication between different levels of the organization.

To maintain the high level of competence and to attract new people to the staff, higher salaries are required. Employees must be valued more, and as one of the nurses put it, politicians can show this through better wages. Responses to the open survey question also expressed that stress, resources, number of personnel and wages were challenges for the future, as was the need for leadership that is clear in its directives, plainly stating our goals and how can we reach them.

A quote from one of the interviewees captures the most central aspect for becoming a healthy organization: We must change the way we think; the tempo is too high. We need to take a step back, calm down and take care of each other.

Conclusions and discussion

What have we learned from the case study of a highly specialized department in a teaching university hospital based on empirical material generated from different kinds of data from a web survey, individual interviews and innovation groups? We have investigated a department with a highly competent female-dominated workforce, almost two-thirds of whom are university educated, working long hours, most of them on permanent contract and with a low turnover rate. Most of the respondents live in households where both spouses put in long working hours.

Our main objective has been to look at different dimensions of a healthy organization by exploring the dual agenda from the perspective of a human service organization. We have looked at indicators of what could be seen as a healthy organization through the way the respondents rate their quality of life. Human service organizations have some special features compared with factories or bureaucracies in that their raw material is people, and in the case of the hospital the patient is the first priority no matter what. Against a general background of changing work-life conditions and challenges where Swedish workers experience more work pressure than do other workers in Western Europe, especially in the health sector, where work intensity has increased, we ask if the so-called dual agenda is adequate or if we need an additional dimension in order to speak of a healthy organization.

In sum we have suggested that exploring the dual agenda from two perspectives the work-household duality and workforce-organization duality sets the scene for analyzing a complete picture of the characteristics of a healthy organization. Our analysis shows that the department at the university hospital, representing our case, can indeed be characterized as a healthy organization. The department has, on average, the least stressed workforce paired with the highest level of organizational work engagement. In terms of characteristics related to personal and family life, it is equally strong: both the perception of work-life balance and satisfaction with life and health are, on average, regarded as the highest in the caring organization.

The combination of high work engagement and fairly moderate work demand can be seen as a contradiction. This impression was further emphasized after analyzing the individual interviews as well as the discourses from the innovation group. The patient as first priority also echoed in the discourse from the qualitative material along with more demanding work, increased work tempo and work intensification. A demanding workplace culture and gender differences were also part of the discourses.

Thus, the design of the study with individual interviews and innovation groups allowed us to see what is behind the aggregate results. Our results indicate that the healthy organization may not be healthy to all occupational groups in the department. Hospitals are known to be hierarchical organizations, with rules and regulations laid out for each level/profession, all related to competence and education. At the top of the hierarchy is the doctor, who has the utmost responsibility for the patient in all respects, directing the clinical investigations, and prescribing interventions as well as medication. The staff at the department in our case literally deals with life and death. For the in-patients, nurses are responsible for daily activities including direct care of the patients, as well as administrative and other activities. When dealing with in-patients, emergency incidents are frequent, which requires staff to be alert and prepared to take instant action. Nurses in a life-saving environment with direct responsibility for and contact with patients need routines to lean on as they are forced to take immediate action. At the same time, the job entails exercising a certain amount of discretion. Although we do not have direct empirical material describing the character of nurses work tasks, we can reason from a theoretical perspective. The work is performed in direct interaction with the patient and in complex situations, which makes it difficult to lean on routines. Instead, it requires that nurses be constantly alert, which places demands on their capabilities to take action under time pressures, demands that can explain why nurses report more work-related stress than employees in the other categories.

We have seen that, in general, there is a high level of work engagement among staff, but surprisingly low work demands. When looking at the groups included in the survey with different occupational status (doctors, nurses and assistant nurses), the picture did not change, except for nurses, who reported significantly more stress related work demand. From the qualitative material, the general impression of high work engagement is strengthened, but so is the discourse about stress related to work demand and increasing work intensity for all groups included in the study. Using a multi-method approach gives us a complex picture. The discourse about stress and workload comes through very strongly in the qualitative material for all occupational groups. Of course we cannot exclude the fact that our respondents are more apt to highlight problems than they are to dwell on positive aspects, but they also give glimpses from a much more rich, diverse and complicated working life of the human service organization than can be revealed by a survey.

Returning to our initial question of whether the dual agenda is adequate or if we need an additional dimension in order to speak of a healthy organization in relation to human service organizations and employees work-life balance, we end up with further questions. Through the combined analysis of material from the survey, individual interviews and innovation groups, occupational status and position in the organization seem vital for employees to speak of a healthy organization. In order to fully understand, we must ask how to get to the meaning of discretion and its relation to stress-related work demand and work-life balance.

References

Ahlberg, Gunnel, Peter Bergman, Lena Ekenvall, Marianne Parmsund, Ulrich Stoetzer, Måns Waldenström, and Magnus Svartengren (2008), Tydliga Strategier och Delaktiga Medarbetare i Friska Företag (Clear Strategies and Participatory Employees in Healthy Organizations), Stockholm, Karolinska Institutet, Uppsala Universitet och Stockholms läns Landsting. [ Links ]

Bäck-Wiklund, Margareta, Tanja Van der Lippe, Laura den Dulk, and Anneke Doornie-Huskies (eds.) (2011), Quality of Life and Work in Europe. Theory, Practice and Policy, London, Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Billquist, Leila, Linda Lane, Margareta Bäck-Wiklund, and Stefan Szücs (2011), Care. A Challenge to Healthy Organizations: A Case Study of a Hospital Unit, The 4th International Community, Work and Family Conference, Tampere, Finland. [ Links ]

Den Dulk, Laura, Margareta Bäck-Wiklund, Suzan Lewis, and Dorottya Redai (2011), Quality of life and work in a changing Europe: a theoretical framework, in Margareta Bäck-Wiklund et al. (eds.), Quality of Life and Work in Europe. Theory, Practice & Policy, London, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 17-31. [ Links ]

Dworkin, Ronald (1978), Taking Rights Seriously, London, Duckworth. [ Links ]

Fleetwood, Steve (2007), Re-thinking work-life balance: editor´s introduction, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18 (3), pp. 351-359. [ Links ]

Hasenfeld, Yeheskel (2010), Human Services as Complex Organizations, Los Angeles, Sage Publications (second edition). [ Links ]

Holmgren, Kristina (2008), Work-Related Stress in Women. Assessment, Prevalence and Return to Work, doctoral disseration, Gothenburg, Department of Clinical Neuroscience and Rehabilitation/Occupational Therapy, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology at Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg. [ Links ]

Houtman, Irene, Peter Smulders, and Ruurt Van den Berg (2006), Werkdruk in Europa: omvang, ontwikkelingen en verklaringen, Tijdschrift voor Arbeidsvraagstukken, 22 (1), pp. 7-21.

Karasek, Robert (1979), Job demands, job decision latitude and mental strain: implications for job redesign, Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, pp. 285-308. [ Links ]

Karasek, Robert, and Töres Theorell (1990), Healthy Work. Stress, Productivity and Reconstruction of Working Life, New York, Basic Books, Harper Collins Publishers. [ Links ]

Lane, Linda, Leila Billquist, Margareta Bäck-Wiklund, and Stefan Szücs (2008a), Healthy Organisations, Quality of Life in a Changing Europe, work package 4, Gothenburg, University of Gothenburg, Department of Social Work. [ Links ]

Lane, Linda, Leila Billquist, Margareta Bäck-Wiklund, and Stefan Szücs (2008b), Sweden. Report on Emerging Themes from the Interviews, research report D4. 1, January 2008, Gothenburg, University of Gothenburg, Department of Social Work. [ Links ]

Lewis, Suzan (2008), Consolidated Report. Case Studies of Healthy Organisations, (D4. 2, March 2008), Middlesex, Middlesex University. [ Links ]

Lewis, Suzan, Maria das Dores Guerreiro, and Julia Brannen (2006), Case studies in work-family research, in Marcie Pitt-Catsouphes, Ellen Kossek, and Stephen Sweet (eds.), The Work and Family Handbook. Multi-Disciplinary Perspectives and Approaches, Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Lewis Suzan, Richenda Gambles, and Rhona Rapoport (2007), The constraints of a work-life balance approach: an international perspective, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18 (3), pp. 360-373. [ Links ]

Lewis, Suzan, David Etherington, Annabelle Mark, and Michael Brookes (2008), Comparative Report on the Innovation Groups (D4. 3, July 2008), Middlesex, Middlesex University. [ Links ]

Lewis, Suzan, Anneke Doorne-Huiskes, Dorottya Redai, and Margarida Barroso (2011), Healthy organizations, in Margareta Bäck-Wiklund et al. (eds.), Quality of Life and Work in Europe. Theory, Practice & Policy, London, Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Lipsky, Michael (2010), Street-Level Bureaucracy. Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services, New York, Russell Sage Foundation. [ Links ]

Szücs, Stefan (2004), Omorganisation Och Ohälsa. Skyddsombuden om Förändringsarbetet Vid Kommunala Arbetsplatser (Reorganization and Sick Leave. The Safety Representatives Report on Organizational Change at Local Government Workplaces), Arbete och Hälsa, 14, Stockholm, Arbetslivsinstitutet. [ Links ]

Szücs, Stefan, and Oskar Cliffordsson (2008), Quality of Life in a Changing Europe, research report, Gothenburg, University of Gothenburg, Centre for Public Sector Research (Cefos). [ Links ]

Szücs, Stefan, Linda Lane, and Margareta Bäck-Wiklund (2008), Perceived satisfaction with work-life balance and overall life satisfaction among Swedish service sector employees, Deliverable 2. 3 March 2008, EU Sixth Framework Programme Project Quality, Utrecht, Utrecht University, pp. 205-240. [ Links ]

Szücs, Stefan, Sonja Drobnic, Laura den Dulk, and Roland Verwiebe (2011), Quality of life and satisfaction with work-life balance, in Margareta Bäck-Wiklund et al. (eds.), Quality of Life and Work in Europe. Theory, Practice & Policy, London, Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Szücs, Stefan, and Örjan Hemström (2010) Effects of reorganization and innovation on long-term sick leave, in Staffan Marklund, and Annika Härenstam (eds.), The Dynamics of Organizations and Health. Work Life in Transition, 5, pp. 93-111. [ Links ]

Valcour, Monique (2007), Work-based resources as moderators of the relationship between work hours and satisfaction with work-family balance, Journal of Applied Psychology, 92 (6), pp. 1512-1523. [ Links ]

Van der Lippe, Tanja, Stefan Szücs, Sonja Drobnic, and Leila Billquist (2011), Data and methods, in Margareta Bäck-Wiklund et al. (eds.), Quality of Life and Work in Europe. Theory, Practice & Policy, London, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 55-74.

Notes

[1] Compare extended discretion, which gives autonomy to decide the premises of the delegation (Dworkin, 1978).

[2] The projectwas funded by the European Commissions Sixth Framework Programme (contract No. 028 945), priority 7, Citizens and Governance in a Knowledge-based Society (March 2006May 2009).

[3] The findings are based on a reanalysis of the interviews as well as previously reported results (Lane et al., 2008a; Lane et al., 2008b; Lewis, 2008; Billquist et al., 2011).