Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Jornal Português de Gastrenterologia

versão impressa ISSN 0872-8178

J Port Gastrenterol. vol.20 no.4 Lisboa jul. 2013

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpg.2012.10.002

CLINICAL CASE

Hypertransaminasemia in celiac disease: Celiac or autoimmune hepatitis?

Elevação das aminotransferases na doença celíaca: hepatite celíaca ou autoimune?

Liliana Eliseua,∗, Sandra Lopesb, Gabriela Duqueb, Maria A. Ciprianoc, Carlos Sofiab

aServiço de Gastrenterologia, Centro Hospitalar do Barlavento Algarvio, Portimão, Portugal

bServiço de Gastrenterologia, Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

cServiço de Anatomia Patológica, Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

*Corresponding author

ABSTRACT

The authors report the case of a young woman presenting with asymptomatic hypertransaminasemia whose etiologic investigation led to the diagnosis of celiac disease. The concomitant existence of antinuclear and anti-smooth muscle antibodies and of elevated sérum immunoglobulin G concentrations raised the hypothesis of autoimmune hepatitis, reason for performing a liver biopsy. The final diagnosis was celiac hepatitis, resolved with dietary treatment alone. Celiac disease is a systemic disorder primarily affecting the small bowel. A variety of liver manifestations have been described and there is an established association with autoimmune hepatic disorders. Isolated elevation of aminotransferases is the most common hepatic presentation, usually reversible with gluten avoidance. Although rarely necessary, liver biopsy may be crucial in selected cases.

Keywords: Celiac disease; Liver diseases; Hepatitis; Autoimmune hepatitis

RESUMO

Os autores relatam o caso de uma jovem, assintomática, com elevação das aminotransferases, cuja investigação etiológica conduziu ao diagnóstico de doença celíaca. A existência concomitante de anticorpos antinucleares e antimúsculo liso e de elevação dos níveis de imunoglobulina G deu origem à hipótese diagnóstica de hepatite autoimune, tendo-se realizado uma biópsia hepática. O diagnóstico final foi de hepatite celíaca, com resolução completa em resposta à terapêutica nutricional. A doença celíaca é uma patologia sistémica com envolvimento primário do intestino delgado. Estão descritas várias manifestações hepáticas, existindo uma associação com as doenças hepáticas autoimunes. A elevação isolada das aminotransferases é a forma de apresentação mais comum, sendo geralmente reversível com a eliminação do glúten da dieta. Apesar de raramente necessária, a biópsia hepática pode ser determinante em casos selecionados.

Palavras-chave: Doença celíaca; Doenças hepáticas; Hepatite; Hepatite autoimune

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is an autoimmune disorder induced by dietary gluten. It is characterized by a chronic inflammatory state of the small intestinal mucosa, resulting in villous atrophy that resolves with a gluten free diet. There is a wide spectrum of presentations, varying from a clinically silent form to the classical malabsorption syndrome.1 Although primarily affecting the small bowel, CD is a multisystem illness. The potential target organs include the liver, pancreas, heart, kidney, thyroid gland, bone, skin and nervous system, giving rise to a variety of extraintestinal manifestations.1,2

A number of hepatobiliary disorders have been documented in patients with CD. The most common pattern of liver damage is a gluten sensitive form of hepatitis (celiac hepatitis). The usual manifestation consists of an isolated elevation of aminotransferases. In this context, liver biopsy is usually of limited value, since the histological findings are nonspecific and there is a complete response to dietary treatment.2 More rarely, CD is associated with a group of liver disorders sharing common genetic factors and immunopathogenesis, such as autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). If this is the case, gluten withdrawal is usually insufficient to normalize liver tests and to prevent progressive liver damage and a specific management is required.3,4

Case report

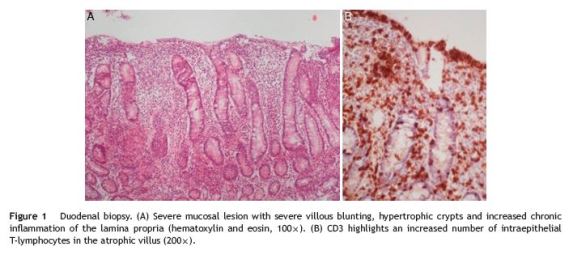

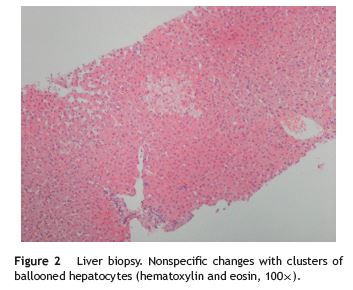

A 21-year-old woman was referred to evaluation because of an unclear elevation of liver enzymes. The patient was asymptomatic and routine laboratory tests made six months earlier incidentally detected a 1.5 to 2-fold elevation of both aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferases (ALT). She denied any history of alcohol or illicit drugs use and she was not taking any medications, including nonprescription ones. There was no evidence of risk factors for viral hepatitis. Her past medical history was unremarkable and no family history of liver or gastrointestinal disorders could be identified. The physical examination was normal, with a body mass index (BMI) of 19 kg/m2 and no signs of liver disease. The initial laboratory study evidenced AST 40 U/L (upper limit of reference, 31 U/L) and ALT 64 U/L (upper limit of reference, 34 U/L), with normal alkaline fosfatase, g-glutamyl transferase, bilirubin and normal hemogram. Abdominal ultrasound examination was normal. A complete screen for the possible etiology of abnormal liver tests was performed. Serologic markers for viral hepatitis were negative. Transferrin saturation, ferritin, ceruloplasmin, a1-antitrypsin and thyroid function tests were normal. The serum protein electrophoresis and immunoglobulin study disclosed an elevation of sérum immunoglobulin (Ig) G concentrations (19.7 g/L; normal 7-16 g/L) and low serum IgA (0.24 g/L; normal 0.7-4 g/L). The autoantibody profile was characterized by positive antinuclear (+++), anti-double-strand DNA (6.1 U/mL; normal < 4.2 U/mL) and anti-smooth muscle antibodies (++++, actin pattern), plus a positivity to IgG anti-transglutaminase (528 U/mL; positive, >10 U/mL) and anti-gliadin antibodies (600 U/mL; positive > 10 U/mL); anti-endomysial antibodies were negative. The patient underwent an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, which showed a slight loss of folds in the second portion of the duodenum. Multiple biopsies were obtained in this location, revealing a complete villous atrophy, crypt lengthening and markedly increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes (Fig. 1), histopathological findings typical of celiac disease (with a destructive pattern, 3c type according to the Marsh-Oberhuber classification). Since the differential diagnosis of AIH versus celiac hepatitis was unclear, it was decided to perform a liver biopsy. The biopsy revealed minimal macrovesicular steatosis and hepatocellular reactive changes, with no evidence of interface hepatitis (Fig. 2), all nonspecific findings, not consistente with AIH. At this point, the simplified AIH score was 6, indicating a probable diagnosis of AIH. According to the overall clinicopathological data, the liver abnormalities were primarily attributed to celiac disease. The patient received dietary counseling and started on a gluten-free diet alone. After 6 months the laboratory reassessment evidenced a complete normalization of aminotransferases (AST 25 U/L, ALT 22 U/L) and decreasing IgG anti-transglutaminase levels (342 U/mL); antinuclear and anti-smooth muscle antibodies remained positive. Her BMI was 21 kg/m2.

Discussion

Hepatic abnormalities are common extraintestinal manifestations of CD. They may arise in patients with the classical malabsorption syndrome or may be the sole presentation in some cases.2 Approximately 27% of adult patients with untreated classic CD have elevated transaminases. Conversely, CD is the potential cause for cryptogenic hypertransaminasemia in 3-4% of cases.5

CD not only may itself injure the liver but it may also coexist with other chronic liver diseases and modify their clinical impact.2 Two main forms of liver damage are recognized: the nonspecific celiac hepatitis and the autoimmune mediated. It is not clearly defined if these two forms are distinct entities or only different ends of a continuous spectrum of liver injury.6,7 Fatty liver disease, viral hepatitis and iron overload liver disease have also been described in patients with CD.3,6

A nonspecific form of liver disease, the so-called celiac hepatitis, is the most common form of hepatic involvement in CD. The pathogenesis remains poorly understood. Malnutrition, ith its metabolic effects, is one of the proposed hypothesis, although nowadays this is an uncommon feature of CD patients.5 An alternative possible mechanism is the direct effect of antigens absorbed from the gut, as a result of an increased permeability of the inflamed intestinal mucosa.8,9 Against this hypothesis is the absence of correlation between intestinal histological changes and the severity of hepatic dysfunction.10 On the other hand, the normalization of aminotransferases with the removal of gluten from the diet suggests a causal relationship between gluten intake/intestinal damage and liver injury.2 Recently, it has been hypothesized that anti-endomysial antibodies may also play a direct role.9 Most patients with this form of hepatitis have no symptoms or signs of liver disease.9-11 Mild to moderate serum levels of AST and/or ALT (with an AST/ALT ratio less than one) are the most common and often only laboratory manifestations, whereas the bilirubin, alkaline fosfatase and g-glutamyl transferase are normal.2,11 Usually, autoantibodies other than the CD ones are not present.6 Liver biopsy is of limited value in this contexto due to the nonspecific nature of the histological findings and the high rate of response after gluten exclusion.2 The histological analysis most commonly shows no abnormalities or non-specific hepatitis, but occasionally fibrosis and cirrhosis can occur.11,12 Studies have reported non-specific findings like focal ductular proliferation, bile duct obstruction, Kuppfer cell hyperplasia, minimal macrovesicular steatosis and minor inflammatory infiltration.6,13 Nevertheless, liver biopsy may be useful in the case of coexisting specific hepatic disorder or when there is a lack of response to diet.2 The decision to perform it must therefore be individualized. A gluten-free diet leads to aminotransferases normalization in 75-95% of cases within a year.10,11,14 In those patients with persistent elevations despite good compliance to glúten exclusion, an alternative etiology should be investigated. Rarely, CD-associated liver disease can manifest as chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and acute liver failure.2,12,14 Screening for CD must be considered in all patients presenting with abnormal liver tests and cryptogenic cirrhosis.5,11,12

There is a well established relation between CD and autoimmune mediated chronic liver diseases, probably sharing immunological mechanisms and susceptibility. AIH, PBC and PSC, with its typical histological features, have all been reported.1,3,4,12,13,15 Two studies found that AIH patients have a higher prevalence of CD, from 4% to 6.4%.15,16 Few of these patients have the classical intestinal manifestations, instead they tend to have nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue and malaise.4,8,10 The clinical impact of gluten withdrawal on the outcome of the liver disorder remains unclear, but it is hypothesized that it may play a role in preventing the evolution to end-stage liver disease.2,12 Nevertheless dietary treatment is necessary to improve symptoms of CD (if present) and to avoid severe chronic complications.1 Testing for AIH is recommended in CD patients with abnormal liver tests. Conversely, screening for CD should be considered for patients with AIH, irrespectively of the existence of gastrointestinal complaints.1,2

The prevalence of PBC is increased from 3 to 20-fold in patients with CD, as demonstrated by two large cohort studies.17,18 On the other hand, CD is more prevalent in PBC patients, from 3% to 7%.4 It should be noted that anti-mitochondrial antibody-negative PBC and false-positive anti-transglutaminase antibodies have been reported in this context.19,20 As in the case of AIH, the impact of glúten avoidance is not well established, but it is determinant to improve symptomatic CD and to prevent complications.2,20

A relation between CD and PSC has been suggested in several case reports and in a population-based study. However the strength of this association is not clearly determined and the benefit of gluten exclusion from the diet was not yet demonstrated.2,13

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and steatohepatitis (NASH) are common disorders in the general population and in celiac patients. Studies found a prevalence of CD in about 3% of individuals with NAFL and NASH.21 Obesity, a major risk factor for nonalcoholic liver disease, is common in patients with CD not only after but also before gluten withdrawal, which could explain the association between these disorders.22 Additional etiopathogenic mechanisms may be the increased intestinal permeability, resulting in bacterial translocation and production of proinflammatory factors, and malabsorption leading to chronic deficiency of lipotropic molecules.23,24 The correlations among CD, obesity and liver disease must be taken into account when establishing the diagnosis and treating celiac patients presenting with elevated liver enzymes.

Acute liver failure and advanced liver disease desserve a special consideration. There are several cases reported in literature and CD was found to be up to 10 times more frequent among patients with chronic liver disease than in the general population.25 The study by Kaukinen and colleagues12 found a high prevalence of CD (4.3%) in patients who underwent liver transplantation. Autoimmune disorders, such as PBC, PSC and AIH were the main etiologies of end-stage liver disease leading to transplantation. This study also describes 4 cases of patients with advanced liver disease who were found to have CD, all of them improving significantly their liver function with gluten withdrawal. Some of the patients in both groups had no apparent symptoms or signs suggesting CD. The authors emphasize that the early detection and treatment of CD may prevent the progression to end-stage liver failure. Therefore, CD must be screened in patients with autoimmune liver disease or hepatitis/cirrhosis of unknown etiology and in those undergoing liver transplantation. Moreover, an essential component of the clinical surveillance after transplantation in CD patients is the assessment of compliance with a gluten-free diet.

The present case illustrates the association between CD and liver disease. Our patient was a young woman presenting with asymptomatic hypertransaminasemia. The initial CD screening was based on autoantibodies, followed by duodenal biopsy. One peculiarity of this patient was the coexistence of a selective IgA deficiency, requiring that the screening for CD was carried out using IgG autoantibodies. This immune defect is one of the conditions known to be associated with CD.1 We emphasize the importance of a confirmatory duodenal biopsy, since false positive serological tests for CD can occur in patients with chronic liver disease and IgG are less specific.1,7 Another relevant feature of our case was the autoantibody profile suggestive of AIH, giving rise to this etiological hypothesis. We have chosen to perform a liver biopsy, which proved to be determinant for the final diagnosis in this specific case. Another possible option would be to recommend gluten withdrawal, control liver enzymes after 6-12 months and continue the investigation only if elevated levels persisted. As expected in this patient, liver tests completely normalized within 6 months of a gluten-free diet.

This case emphasizes the need to screen CD in patients with cryptogenic hypertransaminasemia, irrespective of the existence of gastrointestinal symptoms. It also exemplifies a particular situation in which a liver biopsy is useful to establish the diagnosis of celiac hepatitis.

References

1. AGA Institute. AGA institute medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1977-80. [ Links ]

2. Rubio-Tapia A, Murray J. The liver in celiac disease. Hepatology. 2007;46:1650-8. [ Links ]

3. Freeman HJ. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic disorders in celiac disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1503-8. [ Links ]

4. Volta U. Pathogenesis and clinical significance of liver injury in celiac disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2009;36:62-70. [ Links ]

5. Sainsbury A, Sanders DS, Ford AC. Meta-analysis: coeliac disease and hypertransaminasaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:33-40. [ Links ]

6. Mounajjed T, Oxentenko A, Shmidt E, Smyrk T. The liver in celiac disease. Clinical manifestations, histologic features and response to gluten-free diet in 30 patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:128-37. [ Links ]

7. Carroccio A, Soresi M, Di Prima L, Montalto G. Screening for celiac disease in patients with chronic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1289. [ Links ]

8. Volta U, De Franceschi L, Lari F, Molinaro N, Zoli M, Bianchi FB. Celiac disease hidden by cryptogenic hypertransaminasemia. Lancet. 1998;352:26-9. [ Links ]

9. Peláez-Luna M, Schmulson M, Robles-Díaz G. Intestinal involvement is not sufficient to explain hypertransaminasemia in celiac disease? Med Hypotheses. 2005;65:937-41. [ Links ]

10. Bardella MT, Fraquelli M, Quatrini M, Molteni N, Bianchi P, Conte D. Prevalence of hypertransaminasaemia in adult celiac patients and effects of gluten-free diet. Hepatology. 1995;22:833-6. [ Links ]

11. Duggan JM, Duggan AE. Systematic review: the liver in celiac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:515-8. [ Links ]

12. Kaukinen K, Halme L, Collin P, Färkkilä M, Mäki M, Vehmanen P, et al. Celiac disease in patients with severe liver disease: gluten-free diet may reverse hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:881-8. [ Links ]

13. Jacobsen MB, Fausa O, Elgjo K, Schrumpf E. Hepatic lesion in adult coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:656-62. [ Links ]

14. Ludvigsson JF, Elfström P, Broomé U, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Celiac disease and risk of liver disease: a general populationbased study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:63-9. [ Links ]

15. Volta U, De Franceschi L, Molinaro N, Cassani F, Muratori L, Lenzi M, et al. Frequency and significance of anti-gliadin and anti-endomysial antibodies in autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2190-5. [ Links ]

16. Villalta D, Girolami D, Bidoli E, Bizzaro N, Tampoia M, Liguori M, et al. High prevalence of celiac disease in autoimmune hepatitis detected by anti-tissue transglutaminase autoantibodies. J Clin Lab Anal. 2005;19:6-10. [ Links ]

17. Lawson A, West J, Aithal GP, Logan RF. Autoimmune cholestatic liver disease in people with celiac disease: a populationbased study of their association. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:401-5. [ Links ]

18. Sorensen HT, Thulstrup AM, Blomqvist P, Norgaard B, Fonager K, Ekbom A. Risk of primary biliary liver cirrhosis in patients with celiac disease: Danish and Swedish cohort study. Gut. 1999;44:736-8. [ Links ]

19. Gogos CA, Nikolopoulou V, Zolota V, Siampi V, Vagenakis A. Autoimmune cholangitis in a patient with celiac disease: a case report and review of the literature. J Hepatol. 1999;30:321-4. [ Links ]

20. Floreani A, Betterle C, Baragiotta A, Martini S, Venturi C, Basso D, et al. Prevalence of coeliac disease in primary biliary cirrhosis and of antimitochondrial antibodies in adult coeliac disease patients in Italy. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:258-61. [ Links ]

21. Bardella MT, Valenti L, Pagliari C, Peracchi C, Farè M, Fracanzani AL, et al. Searching for coeliac disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:333-6. [ Links ]

22. Cheng J, Brar PS, Lee AR, Green PH. Body mass index in celiac disease: beneficial effect of a gluten-free diet. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:267-71. [ Links ]

23. Naschitz JE, Yeshurun D, Zuckerman E, Arad E, Boss JH. Massive hepatic steatosis complicating adult celiac disease: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:1186-9. [ Links ]

24. Prasad KK, Debi U, Sinha SK, Nain CK, Singh K. Hepatobiliary disorders in celiac disease: an update. Int J Hepatol. 2011;2011:438184, http://dx.doi.org/10.4061/2011/438184. [ Links ]

25. Stevens FM, McLoughlin RM. Is coeliac disease a potentially treatable cause of liver failure? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:1015-7. [ Links ]

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors must have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence must be in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

*Corresponding author

E-mail address: eliseu.liliana@gmail.com (L. Eliseu).

Received 15 July 2012; accepted 5 October 2012