Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Sociologia

Print version ISSN 0872-3419

Sociologia vol.26 Porto Dec. 2013

FORUM

The Vale do Amanhecer. Healing and spiritualism in a globalized Brazilian new religious movement

O Vale do Amanhecer. Cura e espiritualismo num novo movimento religioso brasileiro globalizado

Le Vale do Amanhecer. Guérison et spiritualisme dans un nouveau mouvement religieux brésilien globalisé

El Vale do Amanhecer. Curación y espiritualismo en un nuevo movimiento religioso brasileño globalizado

Massimo Introvigne1

Center for Studies on New Religions

ABSTRACT

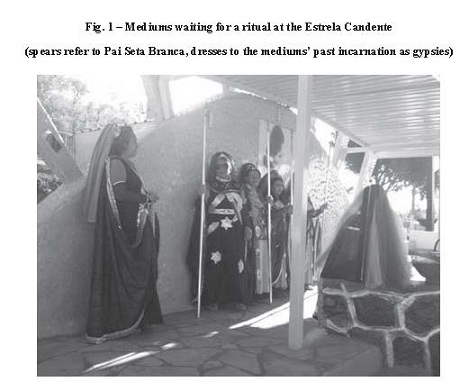

In 2011, the author conducted fieldwork at the Vale do Amanhecer (Valley of Dawn), an incorporated township located four miles near Planaltina, one of the so called satellite towns of the Brazilian capital Brasilia and the center of the largest Brazilian new religious movement, the Spiritualist Christian Order (Ordem Espiritualista Crista, OEC). OEC, founded by Neiva Chaves Zelaya (1925-1985), know to her followers as Tia Neiva (Aunt Neiva), has currently some 500,000 members and 680 temples in Brazil, and several thousand abroad. The group is an offshoot of Kardecist Spiritualism/Spiritism, which is quite well-represented in Brazil, and among the spirits channeled by the OEC mediums are spiritual doctors, gypsies, and African American slaves. Several thousand OEC mediums operate in the Vale do Amanhecer, and they have attracted there millions of pilgrims, most of them seeking healing from the spirits.

Keywords: Vale do Amanhecer; Ordem Espiritualista Crista; Neiva Chaves Zelaya (Tia Neiva); New religious movements.

RESUMO

Em 2011, o autor realizou trabalho de campo no Vale do Amanhecer, municipio localizado a 6 quil6metros de Planaltina, uma das chamadas cidades-satelites de Brasilia, e o centro do maior novo movimento religioso brasileiro, a Ordem Espiritualista Crista (OEC). A EC, fundada por Neiva Chaves Zelaya (1925-1985), conhecida entre os seus seguidores como Tia Neiva, tern atualmente cerca de 500 mil membros e 680 templos no Brasil, e varios milhares no estrangeiro. 0 grupo e urn desdobramento do Espiritualismo/Espiritismo Kardecista, o qual esta muito bern representado no Brasil, e entre os espiritos canalizados pelos mediuns da OEC estao medicos espirituais, ciganos e escravos afro-americanos. Varios milhares de mediuns da OEC actuam no Vale do Amanhecer, atraindo ao local milhoes de peregrinos, a maioria deles em busca de uma cura pelos espiritos.

Palavras-chave: Vale do Amanhecer; Ordem Espiritualista Crista; Neiva Chaves Zelaya (Tia Neiva); Novos movimentos religiosos.

RESUMÉ

En 2011, lauteur réalisa une enquête de terrain chez le Vale do Amanhecer (Vallée de lAurore), une petite ville à six kilomètres de Planaltina, une des villes satellites de la capitale brésilienne Brasilia, et le centre du plus grand nouveau mouvement religieux brésilien, lOrdre Spiritualiste Chrétien (Ordem Espiritualista Cristã, OEC). LOEC, fondé par Neiva Chaves Zelaya (1925-1985), que ses disciples appellent Tia Neiva (Tante Neiva) compte aujourdhui quelques 500.000 membres et 680 temples au Brésil, et plusieurs milliers dans des autres pays. Le mouvement est une dérivation du spiritisme kardéciste, qui a toujours été très présent au Brésil, et parmi les esprits évoqués par les médiums de lOEC il y a des docteurs spirites, des tziganes, et des esclaves afro-américains. Plusieurs milliers de médiums de lOEC travaillent au Vale do Amanhecer, où ils reçoivent des millions de pèlerins, qui cherchent surtout une guérison apportée par les esprits.

Mots-clés: Vale do Amanhecer; Ordem Espiritualista Cristã; Neiva Chaves Zelaya (Tia Neiva); Nouveaux mouvements religieux.

RESUMEN

En 2011, el autor realizó trabajo de campo en el Vale do Amanhecer, un pequeño pueblo a seis kilómetros de Planaltina, llame a una de las ciudades satélite de Brasilia, y el centro del nuevo movimiento religioso más grande de Brasil, la Orden Espiritual Cristiana (OEC). La OEC, fundada por Neiva Chaves Zelaya (1925-1985), conocido entre sus seguidores como Tía Neiva, en la actualidad cuenta con cerca de 500.000 miembros y 680 templos en Brasil y varios millares en el extranjero. El grupo es una rama del Espiritualismo/Espiritismo Kardecista, que está muy bien representado en el Brasil, y entre los espíritus canalizados por los médiuns de OEC se encuentran doctores espirituales, gitanos y esclavos afroamericanos. Varios millares de médiuns de OEC trabajan en el Vale do Amanhecer, atrayendo millones de peregrinos al sitio, la mayoría de ellos en busca de una cura por espíritus.

Palabras clave: Vale do Amanhecer; Orden Espiritual Cristiana; Neiva Chaves Zelaya (Tía Neiva); Nuevos movimientos religiosos.

In June 2011, I visited the Vale do Amanhecer (Valley of Dawn), an incorporated township located four miles near Planaltina, one of the so called satellite towns of the Brazilian capital Brasilia, and the center of the largest Brazilian new religious movement, the Spiritualist Christian Order (Ordem Espiritualista Cristã, OEC). OEC has currently some 500,000 members and 680 temples in Brazil, and several thousand abroad, where temples are maintained in Bolivia (2), Ecuador, Uruguay, the United States, Portugal (2), Germany, and Japan. 150,000 Brazilian members live in the Federal District, and the Vale has a population of 20,000, although it now also hosts Catholic and Pentecostal families. I also spent time in Planaltina, where I counted some 30 Pentecostal houses of worship – there are probably more. I was told by a Catholic priest in Brasilia that in Planaltina Pentecostals do outnumber Catholics in term of Sunday practice, although the majority of the population has still been baptized in the Catholic Church.

Neiva Chaves Zelaya (1925-1985), know to her followers as Tia Neiva (Aunt Neiva), was born in Propriá (Sergipe) on October 30, 1925 and received no formal education. A widow with four sons, she started working in 1955 as a truck driver – reportedly, the first woman in Brazil to work in this capacity – and in 1956 moved to Brasilia, where many trucks were employed in the construction of the new capital. In 1958, she started experiencing visions of spirits, but as a pious Catholic she rejected them. In 1959, however, she met a reputed Spiritualist – or Spiritist, since the large Brazilian Spiritualist movement mostly follows the French variety called Spiritism –, Dona Neném (whose biographical details I did not uncover). Neném interpreted Neiva's phenomena through the lenses of Brazilian Spiritism, and persuaded her that she was a powerful medium, able to channel Pai Seta Branca (Father White Arrow), a powerful Native American spirit. Neiva went into full time mediumship and in 1959 founded with Neném the União Espiritualista Seta Branca in Nucleo Bandeirante, near Brasilia. The messages of Pai Seta Branca quickly became popular, since they included a millennial element connected with the Third Millennium, which resounded with the many prophecies associated with the building of Brasilia.

The spirit ordered his followers to go live communally in the Serra de Ouro, sixty miles from Brasilia. The commune was however plagued by Neiva's frequent illnesses and by disagreements between the two founders. In retrospect, it appears that Neném conceived the Order as a portion of the larger Brazilian Spiritist movement, while Neiva had in mind a genuine new religious movement with several original features. In 1964, the two women parted company. Neném took her followers to Goiânia, while Neiva incorporated the OEC and moved to Taguatinga. In 1968, however, the OEC lost the title to the land in Taguatinga, and the some 250 followers moved to the present location near Planaltina, thus starting the creation of the Vale do Amanhecer.

In the meantime, in 1965 in Taguatinga, Neiva had met Mário Sassi (1921- 1994), a PR officer for the University of Brasilia and a leader of the Catholic left-wing movement JOC (Catholic Youth Workers). Eventually, Sassi left his wife, a sociologist, five children and his job, and went to live with Neiva in the Vale (the two could not marry, since Brazil at that time had no divorce law). Sassi, a city intellectual, became the twin leader of the Vale, and elaborated its complex doctrine based on Neiva's visions. He became also the administrative leader, and his very effective leadership assured the growth of the Vale community from a few hundred to several thousand members when Neiva died on November 15, 1985. After Neiva's death, the OEC was led by a three-member directorate which included Sassi. Soon, however, a disagreement arose between Sassi and the rest of the leadership, which included Neiva's sons, about the legal incorporation of the Vale as a township. This would grant significant advantages in terms of receiving services from the government, but would mean that non-members of the OEC could no longer be prevented from settling in the village. Eventually those favorable to the incorporation prevailed, and Sassi left the Vale trying without great success to establish a smaller movement of his own, the Universal Order of the Great Initiates. He died in 1994 and, possibly also because his group never represented serious competition for the OEC, is remembered in the Vale with no hard feelings. In fact, his historical contribution is acknowledged and celebrated, and his portrait is often displayed in present-day's Vale.

The Vale township appears to be poor, although not very poor by Brazilian standards. Most houses appear simple but decent, and there are no favelas. The visitor cannot but notice that a good part of the population wear quite fancy dresses, which are typical of the OEC and make it a well photographed religious movement in any media reportage about Brazilian religious diversity. Apart from shops selling literature of the movement, religious objects and sacred dresses, there are two main religious centers of the township, the temple and the Estrela Candente (Burning Star: not to be confused with estrela cadente, i.e. shooting star) complex, located something less than one mile from the temple. The Estrela Candente is the main center for the internal activities of the OEC, while outsiders (called clients) seeking cure for physical or spiritual problems are mostly received in the temple.

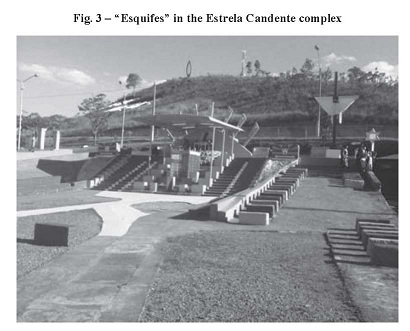

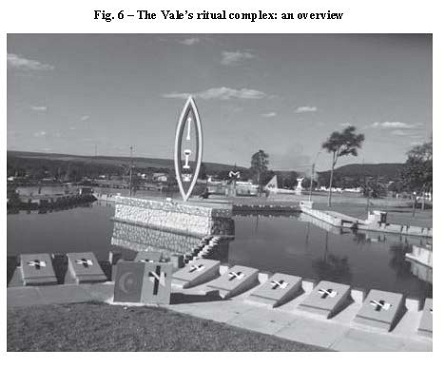

I was able to attend two rituals in the Estrela Candente and to interview several members including one of the most senior doutrinadores leading the rite. Although I did explain that I was already familiar with the main beliefs and practices of the OEC based on its literature, he insisted and explained them from scratch. He started from the Estrela Candente ritual, which is called a work of disintegration on behalf of humanity as a whole. Negative energies are disintegrated and imperfect spirits who harass the living are helped to complete their passage to the higher spheres of the spiritual kingdom. The Estrela Candente is an impressive complex, centered on an artificial lake built by the OEC in the shape of a six-point star with the water of the small river Coatis. Around the lake there are huge carton images of the spiritual entities guiding the movement, crosses and other symbols, portraits of the founders, and several constructions.

The doutrinador insisted on the importance of the esquifes for the work of disintegration. These are 108 large parallelepipeds, each surrounded by a cylinder. Half of these are in blue and half in yellow. Although their ensemble strangely resembles the modernistic art prevailing in Brasilia, my informant insisted that they are of the utmost importance for first calling and then disintegrating negative energies, and for helping wandering spirits in their transition to the light.

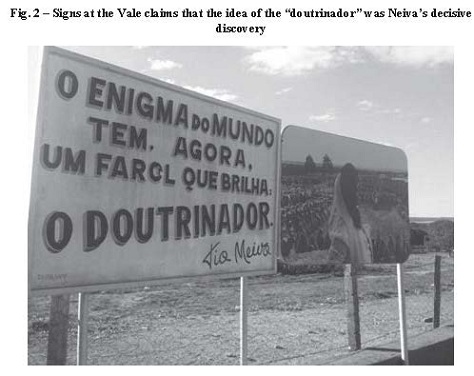

There are different Estrela Candente rituals. I saw two of them, including the loud singing of hymns and collective ritual movements, all aimed at the work of disintegration. Around the lake there are also photographs of the founders (including Sassi) and a small pyramid, where visitors are welcome except during some rituals strictly reserved to members. Inside the pyramid visitors are offered holy salt to be put on the tip of the tongue, and are shown images of several benign entities coming from a variety of traditions, including classical French Spiritism and Theosophy. A large sign not far from the lake reminds the visitor that, according to the founder Tia Neiva, the mystery of the world now has an answer, the doutrinador.

Before asking what exactly a doutrinador is, however, the casual visitor is likely to be impressed by the variety of fancy dresses. They are also comparatively expensive, which explains why the very poor are rare among residing members, since they are expected to pay for them. Many members also bring an arrow spear, a symbol of the main spiritual entity still in touch with the OEG, the same Pai Seta Branca (Father White Arrow) which was channeled by Neiva at the beginning of her career as a medium (and ever since), who is now said to have been Saint Francis of Assisi in an earlier incarnation and to have later reincarnated as a warrior cacique along Lake Titicaca.

The dresses may appear quite casual, but in fact they respect an elaborate code and identify different roles within the OEC and its hierarchy. The senior doutrinator and other members I interviewed all insisted that the main distinctive feature of the OEC, differentiating the movement from the many others which exist within the larger milieu of Brazilian Spiritism, is the difference between two kinds of mediums, the aparás and the doutrinadores. The apará is the classic trance medium, who is able to incorporate or channel both benign and evil spirits. The doutrinador does not go into trances, but is able to dialogue with the spirits channeled by the apará and to interpret what the apará – or, rather, the spirits – say. The dresses reflect the respective relationship of the aparás with the Moon and of the doutrinadores with the Sun. The aparás are mostly female and the doutrinadores mostly male. The latter's dresses are much more sober. Within the two classes of aparás and doutrinadores different dresses identify the seniority. All mediums are called to become masters after a few years of activity within the OEC, but only some become instructors, authorized to teach new mediums.

My informants insisted unanimously that everybody is a natural medium and that I, too, am without doubt a medium, even if I do not realize it. Not everybody, however, is a trance medium, or apará. When one joins the movement and starts the training, he or she will try to incorporate spirits as apará, but may end up without success and be trained as a doutrinador instead. The fact that Tia Neiva was an apará may lead to the assumption that, as it happens in other Spiritist and Spiritualist movements, trance mediums are at the top of the OEC hierarchy. In fact, this is not the case. Aparás are mostly uneducated women, and those middle-class men who have joined the movement are almost all doutrinadores. When interviewing aparás, in case of questions they regarded as difficult, I was constantly referred to a doutrinador, since they know better the doctrine. All top leadership positions are held by doutrinadores.

It is also recommended that aparás do not marry another apará but a doutrinador, since in a family emergence of a spontaneous outburst of spirits at least one doutrinador will be needed to control them.

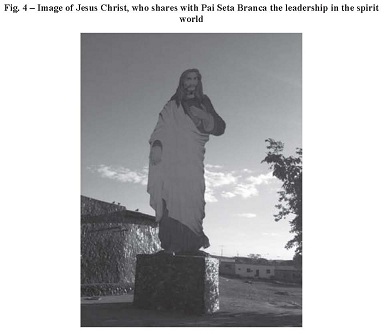

Symbols on the dresses also refer to the guiding spirit of each medium. At the top of the spirit hierarchy are Pai Seta Branca (aka St. Francis of Assisi) and Jesus Christ. Only Tia Neiva was able to channel Pai Seta Branca. If somebody channels Jesus Christ, I found no evidence of this either in the visit or in the literature. The mediums are in touch with four categories of spirits, which shows the eclectic references of the movements. The first includes the pretos velhos, also found in most Afro-Brazilian cults and in the Umbanda, a syncretism of Candomblé and French Spiritism which is an important reference for the OEC. Pretos velhos are the wise spirits of former African slaves brought to Brazil. In the OEC they also have the important function of bringing visitors, clients, and perspective members to the Vale. I was assured that, whatever the circumstances, most assuredly a preto velho instigated my own visit to the township.

The second category of benign spirits includes the caboclos, i.e. Native Brazilians and other Native Americans of old, another recurring group of spirits in Umbanda. Among these are the caboclos of Pai Seta Branca's old tribe. Some of them live in the spirit world, while others have reincarnated twice, first as part of a gypsy tribe and now as members of the OEC. Tia Neiva herself was a leader of that gypsy tribe under the name of Natacha and was at that time initiated by two African slaves, Pai João and Pai Zé Pedro – now functioning as leading pretos velhos –, who also prophesied the birth of the doutrinadores in the 20th century, a recurring episode in the OEC's iconography.

There are two additional categories of spirits of light. One includes spiritual doctors, who may or may not have physically incarnated on Earth. Some of their names, such as Dr. Fritz or Dr. Ralph, recur in other Brazilian Spiritist movements. The other group includes extraterrestrials, particularly those of a planet called Capela, a name also found in the UFO cults literature.

Finally, there are benign spirits outside these categories. They include Mãe Yara, a protector for the whole movement, who incarnated as St. Clare of Assisi, and the often depicted princesses: the white Janaina and the dark-skinned Jurema, Janara, Jandaia and Iracema. The four black princesses were slaves who escaped from a Brazilian fazenda with the help of the fazendeiro's daughter, Janaina. They are guiding spirits only of the doutrinadores, and are never channeled.

In order to understand how the spirits work, one need to visit the temple, a large construction divided into three main areas known as castles, with lateral spaces devoted to preparation for the mediums and instruction. Outside the temple, there is a monument to Pai Seta Branca, a six-pointed star with an arrow. I was offered a detailed tour with rich explanations on the doctrine by an apará, which confirms that there are exceptions to the general rule that those conversant with doctrinal matters are normally the doutrinadores only. While the third area is reserved for curing the most serious illnesses, and a big statue of Pai Seta Branca and a large fresco of Jesus both catch the attention, it is in the first two castles that I saw more action. Clients are attended by a couple including an apará and a doutrinador (sometime, they are husband and wife).

The apará channels his or her spirit guide, a preto velho or caboclo, who after a few words of greeting leaves the apará's body, making room for the spirit disturbing the client, which possesses the medium and explain who he or she is. There is a whole hierarchy of dangerous spirits, from the truly evil to the simply confused, again with similarities to both Brazilian Spiritism and Umbanda. Once the spirit passes from the body of the client to that of the apará, the doutrinador teaches him or her the doctrine, and guides the spirit to cease disturbing the client and go on toward the realm of light, where good principles will continue to be taught. The client is freed from one or more spirits, and can proceed to the second castle, where the apará channels again his or her benign spirit guide, whose words are interpreted by the doutrinador for the benefit of the client. While pretos velhos appear to be good conversationists, caboclos limit themselves to a few words.

The client receives common sense advise, and the OEC emphasizes that in case of physical illnesses is always counseled to see also an earthly doctor and follow the corresponding prescriptions. But to the client it is also normally suggested to come again – one session is rarely enough to solve the problem –, and to consider developing the mediumship which everybody naturally has. The final solution of all the client's problems lies in fact in joining the movement, which automatically means becoming a medium, either apará or doutrinador. All my informants were keen to insist that no money changes hands during the cure. In fact, offers by clients are refused, since the doctrine teaches that they come to the Vale to receive and not to give. Members, on the other hand, are expected to contribute a percentage of their earnings. Some of the doutrinadores have well-paid jobs outside the movement, and this contribute to the OEC's financial stability.

The fact that donations by clients are neither solicited nor accepted, and that clients are advised to also cooperate with medical doctors, has largely shielded the OEC from the secular criticism directed at other spiritual healing groups in Brazil. Criticism by Christian churches is, however, a different matter. The vitriolic criticism of the Catholic Church typical of other Brazilian Spiritist movements is not apparent in the Vale. One informant insisted that Pope John Paul II studied the doctrine for fourteen years, after which he received Tia Neiva and gave her his blessing, a circumstance which is however not confirmed by the records and biographies of the beloved Polish Pope.

I have gathered different opinions from Catholic priests in Brasilia about the Vale. Some believe it will disappear after Neiva's death, an opinion apparently not supported by the movement's numbers, at least so far. Others think that the Vale and similar movements, while obviously not orthodox from a Catholic point of view, should be considered a logical consequence of the Brazilian Church's own mistakes. An excessive focus on social action led many of those seeking mysticism and otherworldly spirituality either to Spiritist groups such as the OEC or to the Pentecostals.

It is precisely the Pentecostals which appears to be the harshest critics of the Vale. Planaltina, where Tia Neiva's grave is in the local cemetery – although well attended, it is not a specially important place of pilgrimage for a movement which does not regard bodies as very important –, is now a hotbed of Pentecostal activities. Some ministers would denounce Neiva as a witch and the Vale's work as the work of the devil. What they, however, do not realize is the similarity between the cures in the Vale and the healing rituals in some of their own churches. In both, evil spirits are named and exorcised, although the names are different. Pentecostalism, at least in its most recent wave largely centered in miracles and deliverance, and the Vale appears to cater to the same audience. Both represent fascinating alternatives for these Catholics feeling that the Brazilian Church, for all its good works, has somewhat lost touch with the miracles and the marvelous.

Notas

1Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR) (Turin, Italy). Direct correspondence to: Massimo Introvigne I CESNUR I Via Confienza, 19 110121 Torino I Italy. E-mail: maxintrovigne@gmail.com