Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Sociologia

versão impressa ISSN 0872-3419

Sociologia vol.26 Porto dez. 2013

ARTIGOS

Toward a Sociology of Wealth: definitions and historical comparisons1

Em direção a uma Sociologia da Riqueza: definições e comparações históricas

Vers une Sociologie de la Richesse: définitions et comparaisons historiques

Hacia una Sociologia de la Riqueza: las definiciones y las comparaciones históricas

Richard Lachmann2

State University of New York at Albany

ABSTRACT

What does it means to be wealthy? Do possessors of significant wealth act in distinct ways that justify considering them a class, an elite or a status group? I explore the implications of various definitions of the wealthy. I review available data for a range of historical societies and then examine if the 1990s explosion of wealth in the United States created a society with a larger stratum of the wealthy than in previous societies. I conclude by identifying a future research agenda that seeks to relate the relative and changing proportions of the wealthy in various societies to other, often non- quantitative evidence of shared occupational and leisure pursuits, family forms and political action.

Keywords : Wealth; Class; Stratification; Status.

RESUMO

O que significa ser rico? Os possuidores de grande riqueza agem de uma maneira distintiva que justifique que sejam considerados como uma classe, uma elite ou um grupo de status? Neste artigo, exploram-se as implicações das várias definições de riqueza. Partindo de uma revisão dos dados disponíveis para uma gama de sociedades históricas, procura-se, de seguida, examinar se a explosão de riqueza verificada nos anos 1990, nos Estados Unidos, conduziu à criação de uma sociedade onde as camadas sociais mais ricas se alargaram, comparativamente com sociedades anteriores. Conclui- se este artigo com a identificação de uma agenda de investigação futura que procura relacionar as proporções relativas e as mudanças verificadas nas classes sociais mais abastadas em diferentes sociedades, muitas vezes provas não quantitativas de atividades de lazer, formas de família e ação política.

Palavras-chave : Riqueza; Classe; Estratificação; Status.

RESUMÉ

Qu'est-ce que cela signifie d'être riche? Les possesseurs de grand richesse acte d'une manière distinctive pour justifier son être considéré comme une classe, un groupe ou un statut d'élite? Cet article explore les implications des différentes définitions de la richesse. Basé sur un examen des données disponibles pour une gamme de sociétés historiques, regardant vers le haut, puis examiner si l'explosion de la richesse trouvé dans les années 1990 aux États-Unis, a conduit à la création d'une société où les couches sociales les plus riches élargies par rapport aux sociétés antérieures. Nous concluons cet article avec l'identification d'un programme de recherches futures qui cherche à relier les proportions relatives et les changements observés dans les classes sociales aisées dans les différentes sociétés, souvent aucune preuve quantitative des activités de loisirs, des formes familiales et l'action politique.

Mots-clés : Richesse; Classe; Stratification; Status.

RESUMEN

¿Qué significa ser rico? Los poseedores de un gran riqueza actúan de una manera distinta para justificar su ser considerado como una clase, un grupo o un estatus de élite? Este artículo explora las implicaciones de las diversas definiciones de la riqueza. Basado en una revisión de los datos disponibles para una amplia gama de sociedades históricas y, a continuación, examinar si la explosión de la riqueza en la década de 1990 en los Estados Unidos, llevó a la creación de una sociedad donde los estratos sociales más ricos se han ampliado en comparación con las sociedades anteriores. Concluimos este artículo con la identificación de una agenda de investigación futura que busca relacionar las proporciones relativas y los cambios observados en las clases sociales más acomodadas en diferentes sociedades, a menudo sin evidencia cuantitativa de actividades de ocio, las formas familiares y la acción política.

Palabras clave : Riqueza; Clase; Estratificación; Status.

This is an essay in definition and historical comparison. I ask what it means to be wealthy. What is the gap, in income or in property, between the wealthiest members of a society and the mass of people? At what point do differences in degree become significant enough to justify labeling some members of a society as wealthy? Do possessors of significant wealth act in distinct ways that justify considering them a class, an elite or a status group?

I begin by exploring the implications of various definitions of the wealthy. I review and compare the few available data sets for historical societies and then examine if the 1990s explosion of wealth, that has been sustained through the stagnation of the 2000s and the crisis of 2008, in the contemporary United States has created a society with a larger stratum of the wealthy than in previous societies. I conclude by identifying a future research agenda that seeks to relate the relative and changing proportions of the wealthy in various societies to other, often non-quantitative evidence of shared occupational and leisure pursuits, family forms and political action.

1. An Undertheorized Problem

Sociologists have devoted surprisingly little attention to identifying the number and characteristics of the wealthiest members of societies and, therefore, have little to say about the effects of wealth on social identity and action. These lacunae are due to the small part that wealth plays in sociological concepts of elites and classes, and to the tendency in stratification research to examine inequality and mobility across entire societies rather than focusing on the top tiers.

Classical sociological theory is concerned more with how power is sustained and exercised rather than with the relative or absolute size of the material advantages realized by those with power. Marxs definition of capitalists was designed to illuminate the nature of exploitation through the production process. A Marxist understanding of the mode of exploitation does not in itself generate an explanation of the distribution of wealth. The relationship between the form of exploitation and the scale of the gap between exploiters and exploited is variable. Marx himself did not attempt to quantify either the number of capitalists (although he was sure that their ranks would fall both absolutely and relatively as capitalism matured) or the differences in incomes and assets from other classes. Elite theory (Mills, 1956; Domhoff, 1983) is concerned with how small cohesive groups exercise power and how those groups reproduce themselves socially and organizationally yet fails to elucidate the material fruits of elite privilege. Webers concept of status group allows for, and he himself describes ((1922) 1978: 304-05, 932-38), a distinctive style of life among those with dramatically greater and/or more enduring wealth than the bulk of society. Yet, Weber never was systematic in identifying or comparing the wealthy across historical or contemporary societies and as a result he did not develop a clear understanding of what aspects of wealth can create a distinctive status group, nor what specific interests such groups hold in contrast to therest of their societies. Bourdieu ((1979) 1984) is more systematic and detailed than Weber or Marx in describing the social characteristics and reproduction of those who occupy the top ranks in society, yet he too doesnt specify the degree or difference in wealth among classes.

The U.S. tradition of status attainment research and theoretical treatments of the relationship between types of societies and patterns of stratification are concerned with differences across entire societies rather than between those at the apex and everyone else. The most sophisticated of such theories identify multiple if overlapping stratification systems based on power, privilege or material wealth, and prestige (Lenski, 1966; Turner, 1984). Lenski and Turner are careful to identify factors that can intensify or disrupt feedback loops that serve to increase or decrease inequality in each of these three realms. The feedback mechanisms account for both growing inequality as the surplus of production over basic needs widens in agrarian societies and a reversal of direction in industrial societies. For Turner, greater equality is common to all industrial societies, while for Lenski the degree of inequality in modern societies varies with the type of political regime.

Lenski and Turner do not distinguish among changes in inequality between a small elite and the rest of society and shifts in distributions of wealth and income among middle strata. Since they do not examine available data from historical societies, their models remain abstract. In order to evaluate the explanatory power of their feedback mechanisms, indeed of any stratification model, we need to determine if they can account for differences in the distribution of wealth across industrial or agrarian societies as well as between each type of society.

If we want to understand the mechanisms by which wealth creates political power and how the rich use their resources to exercise control within their societies, we first must identity the wealthy and distinguish the behaviors particular to them. I begin that task by noting correlations between holders of wealth and of political power and exploring whether the concentration of one is an indicator of the narrowing of the other. Such analyses can provide the basis for the future study of cohesiveness among the wealthy and of how wealth can be used to amass and exercise political power.

Much previous scholarship on differences in wealth and especially in income is concerned with measuring mobility throughout societies. Knowledge of whether individual and familial mobility is high or low does not in itself provide understanding of the existence and extent of the gap between the wealthy elite and the rest of a mobility structure. A high degree of individual mobility can co-exist with a stable and polarized stratification system, just as there can be relatively low levels of inequality in a society with little mobility (Breiger, 1990).

I will, however, examine the strategies wealthy individuals and families adopt in an effort to ensure that their heirs retain the resources and lifestyle of wealth. I explore the extent to which the existence of such strategies, and the resources to ensure the success of such strategies, are integral to a definition of the wealthy.

This article is concerned in the first instance with the mere possession of wealth and how that is defined and measured. It is especially important to devise a clear definition of the wealthy if we hope to evaluate the claims that wealth has become significantly more widespread in the United States in recent years. That premise animates both the best-selling The Millionaire Next Door (Stanley and Danko, 1996) and Kingstons (2000) argument that cohesive classes do not exist in present-day America and therefore sociologists should content themselves with studies of individual mobility and political preferences. Ironically, it also is a premise behind the work of the leading U.S. Marxist scholar of stratification, Erik Wright (1997), who contends that ownership of capital and control over production extends so far down into the middle classes that various contradictory class locations exist in contemporary capitalist societies.

We can find a way toward a useful definition by remembering that Marxs work, like elite theory, is concerned with privilege as well as exploitation. If we want to understand how a total system of economic exploitation or political domination operates we must identify the beneficiaries of such a system. If we can establish standards for separating out a privileged elite or class from all others then we can more appropriately identify the size and dimensions of a special class that needs to be contrasted, not melded, with the vast majority from whose circumstances they fundamentally differ. If that task of differentiation can be accomplished here it will provide a basis for future clarity in discussions of elites and class differences. It also will provide the basis for subsequent studies that can specify the interaction between wealth and political power and explain how mobility into and out of the ranks of the wealthy affects the exercise of political power and vice versa.

2. Definitions of Wealth

David Landes tells the story of Nathan Rothschild, the wealthiest man in the world, who died in 1836 of a routine infection easily cured today for anyone who could find his way to a doctor or a hospital, even a pharmacy (1998: xviii). Landes makes the point that common people at the end of the twentieth century were healthier and lived longer than monarchs and their bankers had two hundred years earlier. By Landes definition, we are all (at least those of us in developed nations) rich today.

Landes notion of wealth is profoundly non-sociological. Landes is describing well-being, not wealth which is about relative social position. He ignores the ways in which wealth and privilege are defined by social contexts and are measured in relation to others with whom one comes into contact.

Veblens definition of wealth is the inverse of Landes notion of well-being. The motive that lies at the root of ownership is emulation

The possession of wealth confers honor; it is an invidious distinction ((1899) 1953: 35). A person is wealthy, in Veblens view, by comparison with others who have less. The invidious comparison now becomes primarily a comparison of the owner with the other members of the group (idem: 36).

Veblens definition points us to the question posed at the start of this article. How much of a difference is necessary to render someone wealthy? Veblen provides a qualitative answer. Veblen believes that wealth needs to be displayed to convey honor, and the most impressive such display is never having to work. The wealth or power must be put in evidence

a life of leisure is the result ((1899) 1953: 42-43). To be wealthy is to have the resources to allow conspicuous leisure and consumption

the utility of both alike for the purposes of reputability lies in the element of waste that is common to both (Veblen (1899) 1953: 71). The honor is even greater if it is inherited rather than earned. By a further refinement, wealth acquired passively by transmission from ancestors or other antecedents presently becomes even more honorific than wealth acquired by the possessors own effort (idem: 37).3 Veblens analysis leads us to the following definitions which frame the analysis in the rest of this article:

- a. Being wealthy is defined as holding enough property to allow oneself and ones heirs in perpetuity to lead a life of conspicuous consumption without ever having to work for material rewards.

b. Conspicuous consumption is defined as the purchase of non-income producing property at a level that is recognized by the majority of the society as so far beyond the norm as to confer special honorific state on the purchaser.

3. The Production and Reproduction of Wealth

Veblens analysis is updated in Robert Franks (1999) Luxury Fever. Frank chronicles in delicious detail the ever escalating cost of purchasing commodities that can stand out from the ever more common items that once would have been regarded as luxurious. Frank points out that a growing portion of national income goes to goods designed to draw what Veblen ((1899) 1953: 18) called invidious comparisons rather than to products that promote well-being, as Landes would predict. Thus, U.S. spending on ever larger homes, more elaborate and bejeweled watches, high performance automobiles that get stuck in traffic on crumbling roads, and $5000 grilles for cooking tainted hamburger meat is rising. At the same time, public investment, even that necessary to allow individuals to actually enjoy their purchases (anti-pollution measures, food inspections, municipal waters systems and other public health programs), is falling.

Individuals eager to earn enough to engage in displays of conspicuous consumption are working ever longer hours, reversing in the U.S. the long-term and worldwide trend toward more leisure (Frank, 1999: 48-53). Frank regards the sacrifice of leisure time for the purchase of luxury goods as a preference for conspicuous over inconspicuous consumption (idem: 90-92). In grouping leisure with genuinely inconspicuous goods such as interesting and worthwhile work, Frank diverges from Veblens view of leisure as the ultimate form of conspicuous consumption.

Veblens classification of leisure is preferable to Franks because it alerts us to the reality that much luxury spending is paid for by income and by debt rather than assets. Thus, evidence of rising luxury consumption might not indicate an increase in the stratum of genuinely wealthy individuals and families in the contemporary United States. While working Saturdays (Frank, 1999: 180) can pay for a Porsche, true wealth allows a standard of living so far beyond the norm that it is not attainable by working overtime. Frank confuses the spread of certain emblems of wealth with consistent conspicuous consumption in numerous realms, all paid for with a return on wealth, not by salaries earned by working overlong hours.

We are left with an actuarial and an historical problem. We can calculate the amount needed to provide for leisure in any society for perpetual generations of heirs. However, the level of spending needed to display enough conspicuous consumption to allow someone to be regarded with honor varies across time and place. That level can be determined only by empirical investigation to identify the meaningful break points between the honored elite and everyone else in particular societies. Inheritance patterns are an additional historical variable. Less wealth is needed to endow heirs where primogeniture is practiced, and where estates are divided the number of offspring becomes crucial.4

Midlarsky (1999) argues that inequality is automatically produced by scarcity of valued commodities (with land being the most important and highly inelastic commodity through most of human history). Midlarsky contrasts exponential and fractal distributions. The former is typical of peasant societies with moderate scarcity of land. Rising population and/or geographical or technical limitations on the opening of new farmland can cause the scarcity. Fractal inequality is much more severe. Under that pattern, a small elite maintains its hold on a scarce resource through institutionalized power, most often in the form of the state. While the elite holds most of the scarce good, the remainder is subdivided again and again among the rest of the population, widening the gap between the elite and the rest through the impoverishment of the masses. Fractal inequality is extreme and becomes more so, since the elites advantages (large estates, trade routes, markets, colonies) arent divided and dont circulate. The elites benefit from positive feedback between concentrated resources and the powerful institutions the narrow elites invest in to guard their hold on those resources.

Midlarsky is concerned with the effect of different levels of inequality on state stability and democracy, and so neglects to compare the actual levels of inequality and wealth across the historical cases he examines. Shanin (1972) has found that centripetal forces reduce inequality between rich and poor peasants, undermining the repeated subdivisions among non-elites that are the primary factor in Midlarskys analysis. Conversely, centrifugal forces, such as divisions among heirs, political expropriation, and economic setbacks, made it impossible for all but a minority of Russian aristocrats to maintain their vast edge over commoners for more than a few generations in pre- Revolutionary Russia. Thus, neither exponential nor fractal inequality are stable in most cases. The extent of inequality and its duration must be studied historically before we can develop typologies and reach conclusions.

4. Wealth in Agrarian Societies

It is easy, in most historical societies, to identify the wealthiest stratum. Income and power were determined by control over land. Peasants were the vast majority in most pre-modern societies. Peasants varied in the share of production they had to surrender to landlords in return for use rights to land. The portion of the population that collected rents from the users of land was quite small in virtually every historical society. Land in European feudal societies was not owned. Instead, peasants had rights to work land, while landlords, officials and clerics enjoyed the right to collect rents in kind or in cash, and/or to demand labor dues from peasants. Non-peasants property consisted mainly of such income rights. When landlords bought land, they actually were buying income rights. Indeed, land was valued and sold as a multiple of the annual income it generated for its landlord. Measures of the income landlords, officials and clerics received from land therefore can serve as a proxy for the distribution of non- peasant property and vice versa.

The income collected by landlords was narrowly distributed. Various local studies for France in the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries find that seigneurs made up 1-2% of the population and collected a quarter to a third of total agricultural production (Le Roy Ladurie, 1975; Leon, 1966). Spanish nobles collected about a third of agrarian income (Vilar, 1962), as did English landlords in the centuries prior to the Reformation (Lachmann, 1987: chapter 3). We can make only a rough calculation of landlord incomes as multiples of peasant incomes since we have little data on the distribution of landholdings and incomes among landlords and peasants. If we assume that rich peasants had three times as much land as the average peasant (which was typical in many of the villages for which we have records) then the average landlord had an income from 4 to 17 times that of rich peasants. That relatively modest gap between many nobles and rich peasants masks the reality of large differences among landlords. Especially in countries like France, where noble landholdings were subdivided, many landlords lived more like very rich peasants than like the great magnates. Unfortunately, we have only case studies and anecdotal evidence to support the view (with which most historians concur) that a small minority of landlords made up a wealthy elite removed in consumption patterns and political power from lesser landlords and peasants alike.

Lesser landlords attempted to uphold the standards of noble behavior, pursuing noble leisure activities and fulfilling obligations of hospitality while shunning commercial enterprise (Elias, (1969) 1983: 78-116). This pursuit of honor served to impoverish lesser landlords over time as they outspent their incomes and mortgaged their estates (Stone and Stone, 1984). These behaviors became essential to noble self- definition once landlords no longer were required or allowed to maintain armed retinues that challenged more often than they assisted royal armies (Stone, 1965). Impoverishment was more rapid and more widespread among nobles (such as the French) where property was divided among heirs, than where primogeniture was practiced (such as in England).

Landlords in medieval and early modern Europe deployed their wealth to sustain membership in a status group defined by aristocratic ideals of leisure and hospitality and which was the basis of political power (Clark, 1995). Nobles devotion of their wealth to the maintenance of everything that traditionally held the lower-ranking strata at a distance (Elias, (1969) 1983: 95) had the long-term effect of fatally undermining the ability of all but the greatest landlords to preserve the means for the practice and reproduction of their status. Only a few landlords were wealthy enough to sustain both the material bases and status behaviors of their positions over generations, just as most of the contemporary Americans described by Frank indulge in luxurious consumption at the cost both of their leisure time and of their heirs prospects to attain wealth through inheritance.

5. Early Modern England

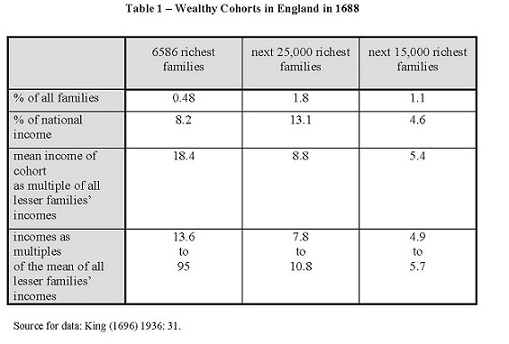

Gregory Kings study of England in 1688 is the earliest comprehensive survey of income distribution in a predominately agrarian society. King listed families by title or occupation and gave the average household income for each category ((1696) 1936:31). Kings survey, unlike the others we will examine, is for income rather than assets. However, since the bulk of English wealth still was in land in 1688, Kings income data remains a good proxy for wealth, especially for the landowners who make up the majority of the top strata. Two possible break points suggest themselves.

The first cohort consists of the richest one-half of one percent of families, all of whom enjoyed incomes at least 13.6 times the average of the other 99.5% of English families. Two-thirds of those families came from the top four orders of lay nobles and the spiritual lords, while the remaining third were the wealthiest merchants and traders. These families clearly fit our definition of the wealthy. They spent 80-90% of their income, according to Kings estimates, much of that on conspicuous consumption (Stone and Stone, 1984: 295-328). The lords and other nobles were able to sustain their high incomes and spending over the very long-term because their wealth was in land which was kept intact through primogeniture, ensuring that a single head of household would receive and spend the familys income on an elaborate household. Furthermore, land in England generated an income that rose absolutely and relatively to other sources up to the nineteenth century (Allen, 1992), allowing landowners to widen their

advantage over other non-landowning groups in subsequent centuries. Furthermore, the land was received in inheritance and managed by hired stewards, allowing the landlords to spend their entire lives at leisure.

The second cohort includes gentleman (gentry who held only a single manor), high-level officeholders, and lesser merchants and traders. The gentlemen enjoyed incomes of more than ten times the average of all the lesser cohorts. The other members of this cohort enjoyed incomes of 7.8 to 9.3 times that of the lesser cohorts.

The third cohort consists of lesser officeholders and lawyers. The lawyers had average incomes two-thirds higher than the best-off families outside this group. Put another way, the average lawyers family enjoyed an annual income slightly less than five times the average of the 96.6% of English families outside this group.

The second and third cohorts were able to indulge in conspicuous consumption, albeit at progressively lesser levels than the richest families. However, since these cohorts, except for the gentleman landowners, had incomes that were derived from work rather than wealth they were unable to sustain their high consumption if they lost their offices or professions or otherwise could not continue to work. Their ability to pass on their positions to their children varied. Gentlemen practiced primogeniture and so were able to pass on their wealth and standing to their heirs just like the greater landlords unless they sought to match the spending levels of the top cohort in which case they took on debt and lost their lands.

The other members of these cohorts lacked the assets to ensure that an heir would equal their income. Often they were able to help their heirs, but that was not a result of their wealth per se. Political connections and education were narrowly held and often could be passed down or reproduced, allowing many though not all officeholders and lawyers to maintain their family incomes in their eldest sons. Commerce was more volatile than agriculture or politics, and these lesser merchants were more vulnerable to economic fluctuations and heightened competition over generations than their wealthier counterparts in the first cohort, and so less able to ensure a similar position of relative wealth for heirs over generations (Clark, 1977; Simpson, 1961).

We can conclude that among the families of the second and third cohorts, only the gentlemen of the second cohort might meet our definition of the wealthy. If we add the gentlemen to the population of the first cohort, we would be left with 18,586 out of 1,360,586 English families, or 1.35% of the total, who can be considered wealthy.

6. Florence

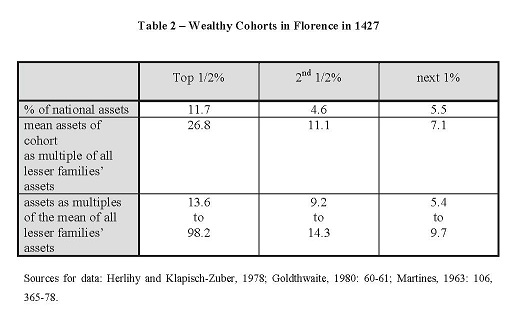

The other relatively comprehensive pre-modern data set is from the Florentine Catasto of 1427 (Herlihy and Klapisch-Zuber, 1978; Goldthwaite, 1980: 60-61; Martines, 1963: 106, 365-78). The Catasto lists the assets of each household in the Florentine commune, including smaller captive cities and the countryside. Table Two parallels the results for England in 1688, offering three strata of wealth.

We find that the truly wealthy comprised a smaller portion of the population in fifteenth century Florence than was the case in England two hundred and fifty years later. The wealthiest 1/2% of Florentines held 11.7% of total household wealth compared with 8.2% in England. The range of wealth for this top cohort in relation to the wealth of all lesser households, 13.6 to 98.2, is almost exactly the same as in England, 13.6 to 99. However, the mean wealth for this top cohort as a multiple of the other 99.5% is, at 26.8, almost half again as large as the multiple of the mean income of the top 1/2% in England compared with the rest of the population at 18.4. The larger multiple reflects the enormous concentration of wealth in the hands of the top dozen Florentine families. The concentration of wealth drops off abruptly, with the second 1/2% enjoying a mean wealth only 11 times that of the rest of the population. When we get to the next 1% the ratio is only 7.

The second Florentine cohort hovers just above our definition of the wealthy, while the third cohort (the second richest 1%) falls below our definition, since they lacked a great enough multiple of wealth to engage in truly conspicuous consumption. Indeed, historians descriptions of this group show a sharp drop-off from the size of the palaces, entourages, dowries, and art collections characteristic of the truly wealthy Florentines. Most Florentines in the top cohorts worked, however those in the richest group possessed enough wealth to spend months vacationing each year at their country estates. Only families in the first cohort were able to accumulate enough wealth to ensure that their heirs could live off passive income from land and state bonds in future generations. The heirs of those in the second and third cohorts suffered real and relative declines in income as Florences commercial and manufacturing position deteriorated in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (Litchfield, 1986). The first cohort was not only a status group but a political bloc, dominating the offices of the Florentine government (idem).

7. Late Eighteenth Century Comparisons and the Concentration of American Wealth

We can gain a sense of how the United States at the beginning of its independent existence compared with European societies emerging from feudalism from data compiled by Lee Soltow (1989).

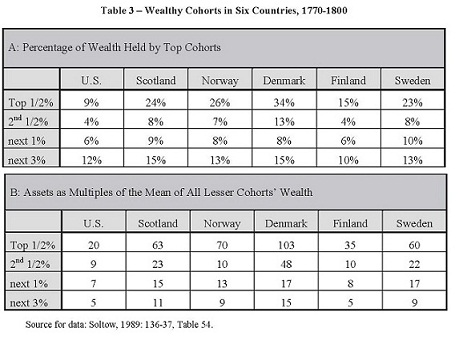

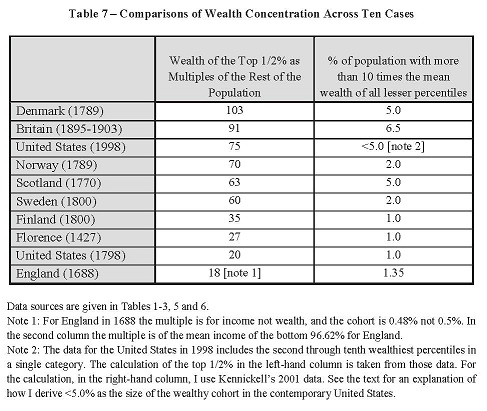

The United States enjoyed a far more equal distribution of wealth than the five European countries for which Soltow was able to find comparable data for the last decades of the eighteenth century. The richest 1/2% of Americans in 1798 occupied almost the same relative position as their counterparts in 1688 England, holding 9% vs. 8.2% of wealth, a multiple of 20 times the holdings of the bottom 95% compared to the English top tiers 18.4 multiple of the bottom 96.4%.

The other five countries examined by Soltow had far more extreme concentrations of wealth, ranging from the 15% of total assets and a 35 multiple of the mean of all lesser cohorts wealth in Finland to an astounding 34% and multiple of 103 in Denmark. If we take a multiple of more than ten times the assets of all lesser cohorts as the indicator of sufficient wealth to indulge in consumption at a level conspicuously beyond others, then we find that the United States had the smallest cohort of wealthy of any society in this era (1/2% vs. 1% for Finland, 2% for Norway and Sweden and 5% for Denmark and Scotland). The United States in the early years of the Republic stands apart from other largely agrarian societies of that era, and along with England of a century earlier and the Florentine city-state of three centuries earlier as relatively egalitarian.

Soltow argues that America in 1798 had greater income equality than in the late colonial period, mainly because the British defeat in the Revolutionary War had led to seizure of many of the largest estates, which belonged to Loyalists, and to the reform of inheritance laws, which served to divide large estates among heirs (1989: 141-51). Such changes did not effect the total wealth of the new nation, nor its per capita level; indeed, Americas average wealth was as large, or almost as large, as that in any country of that era (idem: 140).

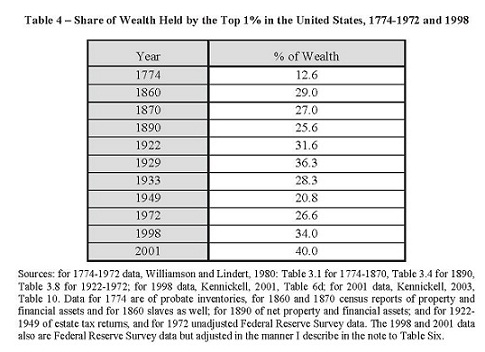

Williamson and Linderts (1980) less fine-grained data5 on the distribution of assets point to the period from 1840 to 1860 as the moment when the distribution of wealth became dramatically more unequal in the United States. Their data are not strictly comparable to Soltows or to Kennickells (2001; 2003) for the United States in 1998 and 2001. However, Williamson and Lindert are useful in showing change over the entire history of the United States.

U.S. wealth inequality declined somewhat after the Civil War, mainly because the emancipation of slaves and destruction in the war undermined the great slaveholding fortunes of the South. Inequality rose to a peak in 1929, then declined substantially with the stock market crash, the New Deal and the broadening of the middle class in the post- war decades. Wealth concentration rose again sometime after the mid-1970s, reaching levels unprecedented for the U.S. with the peak of the Clinton bubble in 2001.

8. Britain at Its Imperial Height

Nations can become wealthier when they achieve dominance in the world economy, as Britain accomplished at the end of the eighteenth century and the United States at the start of the twentieth century (Lachmann, 2003). At issue here is how such imperial power affects the concentration of wealth within the hegemonic polity.

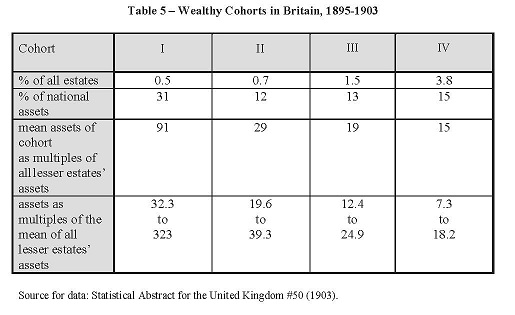

British commerce and industry expanded from the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries, but the main beneficiaries were the top ½%, who almost tripled their share of national wealth from 11% in 1688 to 31% by the turn of the twentieth century.

The next cohorts benefited along with the richest ½% from Britains economic and imperial hegemony. The next 3%, which held 24% of the nations wealth in 1688, became the next 6% (Cohorts II-IV), which held 40% two centuries later. Compared with their inferiors, the second cohort was 8.8 times as well off in 1688, while cohorts II-IV were on average 21 times richer than those below them at the turn of the twentieth century.

All four of the top cohorts in Britain at the turn of the twentieth century can be considered wealthy, which means that 6.5% of the population was wealthy according to our definition. This is, by far, the largest portion of the population in any of the cases considered here to achieve that distinction. The four cohorts shared a common lifestyle, which combined the illusion of leisure in country life with the pursuit of wealth and the exercise of political power at both the local and national levels (Stone and Stone, 1984; Mann, 1993).

The British data suggest that a world empire is better suited than either a commercial city-state or the European agrarian societies of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries for producing a relatively large cohort of wealthy. Florence had a far more volatile economy than did Britain in either 1688 or 1895-1903. Only a single cohort of less than 1% of the population was able to sustain true wealth under such economic and political flux. That greater relative wealth for the Florentine rich was won at the expense of the next cohort, which fell far behind the second English cohort. Only in late Victorian England, at the height of British financial and imperial dominance of the world (Arrighi and Silver, 1999), did a super-rich top cohort co-exist with still wealthy secondary cohorts totaling 6% of the population. This relatively broad distribution of wealth is more extraordinary in that it coincided with an enormous multiple of wealth for the very top cohort of 91 times the average assets of the non- wealthy portion of the population, the second highest such figure recorded, exceeded only by largely agrarian Denmark in 1789.

9. The Contemporary United States

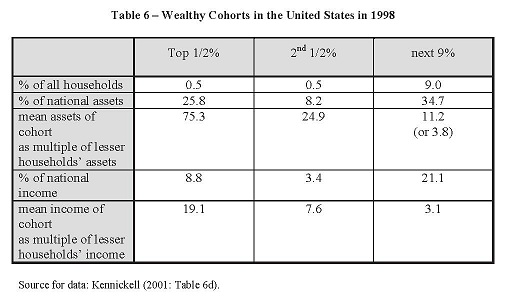

Popular and some academic accounts trumpet the supposed broadening of wealth in the United States in the 1990s. The Millionaire Next Door became a long- standing bestseller as it celebrated the myriad of people who got rich by working hard at boring jobs, running bland small businesses, and living frugally (Stanley and Danko, 1996). Stanley and Danko present the contemporary millionaires lack of ostentation as a virtue, pointing out that most of them would not be millionaires for long if they attempted to live like the millionaires of old. Thus, these estimated 3.5 million households enjoy material well being which meets Landes notion of wealth but are unable to enjoy a perpetual life of leisure and the ostentatious display that conforms to Veblens and our definitions of the wealthy. The word remains the same, but the meaning changes, and data on income and wealth indicate that it requires much more than a million to really distinguish oneself from the vast American middle class and so meet the definition of wealthy.

The top 1/2% in the United States held a quarter of all financial assets in 1998. This is equivalent to the share held by the same cohort in Florence in 1427 and to the top 1/2% in the late eighteenth century agrarian societies of Scotland, Norway and Sweden. That share is triple that held by the top 1/2% in 1688 England and early Republican America. It is exceeded only by the 34% held by the Danish top 1/2% in 1789 and by the 31% of the top 1/2% in late imperial Britain.

The very wealthiest Americans among the top 1/2% meet the highest historical standards for relative wealth. The richest grandee in Spain (in 1600 had) an estimated annual income of 160,000 ducats which was 5333 times as large as the annual wage for an average laborer of 30 ducats (Kamen, 1991: 243). The average U.S. household income in 1997 was $62,400 (Congressional Budget Office, 2001). The same multiple would yield an income of $333 million. The I.R.S. reported that the top 400 tax returns (0.0004% of all returns) had an average gross income of $110.5 million (New York Times, 2001). In other words, the richest 0.0004% of Americans had incomes 1771 times the national average. The top category in British estate tax returns a century earlier was a larger 0.013% of the population with an estate 1564 times the average of the bottom 93.5% of estates. Late Victorian Britain, thus, produced a group of superrich that by this measure was thirty times as large as that in the United States near the height of the Clinton financial bubble.

The second half percent of American households also are wealthy by comparative historical standards. Their means assets are 24.9 times that of the bottom 99% of households in the United States in 1998. That is comparable to Scotland in 1770 (23 times) and Sweden in 1800 (22 times) and exceeds their counterparts in 1427 Florence and 1688 England (both around 11 times), 1800 Finland and 1789 Norway (both 10 times), and the United States in 1800 (9 times). Only Britain at the turn of the twentieth century had a wealthier second half percent with mean assets 29 times that of the bottom 99% of the population.

The third cohort, which includes two-thirds of the millionaires profiled by Stanley and Danko, is at the edge of being wealthy if taken as a whole. Their assets are eleven times the national average. However, if we recognize that the bottom 60% of U.S. households have no net financial wealth (Keister, 2000: 85), then this third cohort only has 3.7 times the assets of the next 30%. That small multiple helps explain Stanley and Dankos observation that most American millionaires live surrounded by less wealthy folk and wear clothes and drive cars that are the same as ordinary middle income Americans. That consumption pattern is similar to that historians describe for the second Florentine cohort with its 4.1 ratio of assets to those under them. The 3.7 multiple of this third American cohort is close to its 3.1 multiple for income over the bottom 90% (Kennickell, 2001), indicating that assets add little to this cohorts relative standing.

Clearly, the large size of the third cohort, at 9% of the population, masks the presence of some additional percentiles of wealthy Americans. Kennickells (2003) study of wealth in 2001, divides those 9 percentiles into two groups, the 95th through 98th percentiles and the 90th through 94th. His latter study, unfortunately, collapses the top two cohorts of 1998 into a single top percentile and is not exactly comparable with his earlier study in some other ways. (Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez study the distribution of income, not wealth, which is why I use Kennickells work rather than theirs.) However, the 95th through 98th percentiles, when measured at the top of the stock market bubble in 2001, do fall into the ranks of the wealthy. Their mean assets are 20.3 times those of the bottom 95% of American families. Thus, we can conclude that at the height of the Clinton bubble, 5% of American families were wealthy, a total that is matched by late eighteenth century Denmark and Scotland and exceeded only by imperial Britain.

Households in the 95th through 98th percentiles had a mean net worth of $2,060,000 and a minimum net worth of $1,090,000 (Kennickell, 2003, Table 106). Assuming an 8% annual return in perpetuity (which is generous), the average nest egg of this cohort would produce an annual income 3.2 times the mean income of the 95% of American families below them, while the minimum net worth would produce an income 1.7 times the bottom 95% of families mean income.7 This cohort is at the edge of being wealthy. They can sustain a level of conspicuous consumption while living a life of leisure, although only at a level two to three times that of the mass of Americans living below them. These families positions of wealth would be endangered by subdivisions among heirs and probably has been undermined by the stock market declines following the bursting of the bubble after these 2001 data were collected.

Conclusion

We have been able to identify clear break points between the wealthy and the rest of the population in the ten cases for which we have clear data.

The rich not only are different from you and me; there are not many of them in any of the societies examined. Britain at the height of its imperial power and wealth had the largest recorded cohort of wealthy at 6.5%. Its hegemonic successor, the contemporary United States, and the agrarian societies of the late eighteenth century (Denmark, Scotland, Norway and Sweden) occupy a middle ground with wealthy cohorts of 2% to 5%. Agrarian Finland, and the more dynamic mixed agrarian/commercial societies of 1427 Florence, 1798 America and 1688 England have the smallest cohorts of the wealthy at 1% to 1.35%. That result contradicts Midlarskys claim that fractal distributions of assets are most likely to occur in the more rigid polities and economies.

There also is a clear relationship between the size of the wealthy cohort and the degree to which that cohorts wealth exceeds that of the rest of the population. Extremely wealthy top cohorts, with wealth multiples of 60 to 103, are found in agrarian or imperial societies and coexist with relatively large secondary cohorts of the wealthy.

The agrarian and commercial societies in which only 1% of the population is wealthy also have lower multiples of wealth at 30 or less.

In all the cases studied only one or a few percent of a societys population is able to engage in true conspicuous consumption, defined by its lavishness in relation to other members of society rather than in relation to generally rising historical standards. That small group of wealthy also is the only fraction of society able to sustain such a standard of living from passive rather than earned income. As a result, only that small group is able to fulfill the other half of Veblens model of status honor, a life of leisure. Further, since this wealthy elite maintains its standard of living from assets that need not be added to by work, these families can sustain their high standing in perpetuity provided they avoid subdivision among multiple heirs, foolish investment decisions, inheritance taxes, or political expropriation.

The small size of a wealthy cohort in these societies points to the value of pursuing a research agenda that focuses on this narrow elite. We need to deepen our understanding of mobility into and out of this narrow elite. Such studies of changes in the number and quality of elite positions need to be separated from broader analyses of mobility through a society. Status attainment research easily can confound evidence of mobility among the mass of the population with very different patterns among the truly wealthy.

Finally, we should disentangle the noise of regular falls by individual families out of this elite cohort from the more significant extinctions of large groups of wealthy. How are economies and polities affected by large-scale elimination of wealthy cohorts, such as the revolutionary elimination of nobilities and the expropriations and evaporations of wealth following defeats in war, decolonization, or economic collapses? How quickly are the ranks of the wealthy reoccupied, and from where do the members of the new cohort come? Conversely, how are societies affected when a wealthy cohort is successful in protecting its privilege into the distant future? For example, what would be the consequences of a permanent abolition of the inheritance tax in the United States? Now that we can clearly identify the subjects of study, we will better be able to ask meaningful questions and identify the proper bases for developing answers.

Bibliographical references

ALLEN, Robert C. (1992), Enclosure and the Yeoman: The Agricultural Development of the South Midlands, 1450-1850, Oxford, Clarendon. [ Links ]

ARRIGHI, Giovanni; SILVER, Beverly J. (1999), Chaos and Governance in the Modern World System, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre ((1979) 1984), Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, Cambridge, Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

BREIGER, Ronald (1990), Introduction: on the structural analysis of social mobility, in Ronald Breiger (ed.), Social Mobility and Social Structure, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1-23. [ Links ]

CLARK, Peter (1977), English Provincial Life, Sussex, Harvester. [ Links ]

CLARK, Samuel (1995), State and Status: The Rise of the State and Aristocratic Power in Western Europe, Montreal, McGill and Queens University Press. [ Links ]

CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE (2001), Historical Effective Tax Rates, 1979-1997. Available on: http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdoc.cfm?index=2838&type=1 [ Links ]

DOMHOFF, G. William (1983), Who Rules America Now? A View for the 80s, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

ELIAS, Norbert ((1969) 1983), The Court Society, New York, Pantheon. [ Links ]

FRANK, Robert H. (1999), Luxury Fever: Why Money Fails to Satisfy in an Era of Excess, New York, Free Press. [ Links ]

GOLDTHWAITE, Richard A. (1980), The Building of Renaissance Florence: An Economic and Social History, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

HERLIHY, David; KLAPISCH-ZUBER, Christiane (1978), Les Toscans et leurs familles, Paris, Presses de la Fondation Nationale des Sciences politiques. [ Links ]

HOWELL, Cicely (1983), Land, Family and Inheritance in Transition: Kibworth Harcourt 1280-1700, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

KAMEN, Henry (1991), Spain 1469-1714: A Study of Conflict, London, Longman. [ Links ]

KEISTER, Lisa A. (2000), Wealth in America: Trends in Wealth Inequality, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

KENNICKELL, Arthur B. (2001), An Examination of Changes in the Distribution of Wealth From 1989 to 1998: Evidence From the Survey of Consumer Finance, Washington, Federal Reserve Board. [ Links ]

- (2003), A Rolling Tide: Changes in the Distribution of Wealth in the U.S., 1989-2001, Washington, Federal Reserve Board. [ Links ]

KING, Gregory ((1696) 1936), Natural and Political Observations and Conclusions upon the State and Condition of England, in Two Tracts, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

KINGSTON, Paul A. (2000), The Classless Society, Stanford, Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

LACHMANN, Richard (1987), From Manor to Market: Structural Change in England, 1536-1640, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press. [ Links ]

– (2003), Elite Self-Interest and Economic Decline in Early Modern Europe, in American Sociological Review, 68, 346-372. [ Links ]

LANDES, David (1998), The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor, New York, Norton. [ Links ]

LENSKI, Gerhard (1966), Power and Privilege: A Theory of Social Stratification, New York, McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

LEON, Pierre (1966) (ed.), Structures Economiques et Problemes Sociaux du Monde Rural dans la France du Sud-est, Paris, CNRS. [ Links ]

LE ROY LADURIE, Emmanuel (1975), Un Modele Septentrional: Les Campagnes Parisiennes (XVI-XVII siecles), in Annales ESC, vol. 30, 6, pp. 1397-1413. [ Links ]

LITCHFIELD, R. Burr (1986), The Emergence of a Bureaucracy: The Florentine Patricians, 1530-1790, Princeton, Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

MANN, Michael (1993), The Sources of Social Power volume II: the rise of classes and nation- states, 1760-1914, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

MARTINES, Lauro (1963), The Social World of the Florentine Humanists, 1390-1460, Princeton, Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

MIDLARSKY, Manus I. (1999), The Evolution of Inequality: War, State Survival, and Democracy in Comparative Perspective, Stanford, Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

MILLS, C. Wright (1956), The Power Elite, New York, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

NEW YORK TIMES (2001), Really Rich vs. Simply Affluent, May 15, 2001. [ Links ]

SHANIN, Teodor (1972), The Awkward Class, Oxford, Clarendon. [ Links ]

SIMPSON, Alan (1961), The Wealth of the Gentry 1540-1660, Chicago, University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

SOLTOW, Lee (1989), Distribution of Wealth and Income in the United States in 1798, Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press. [ Links ]

STANLEY, T.; DANKO, W. (1996), The Millionaire Next Door, Atlanta, Longstreet. [ Links ]

STATISTICAL ABSTRACT FOR THE UNITED KINGDOM #50 (1903), London: His Majestys Stationary Office. [ Links ]

STONE, Lawrence (1965), The Crisis of the Aristocracy, 1558-1641, New York, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

STONE, Lawrence; STONE, Jeanne C. Fawtier (1984), An Open Elite? England 1540-1880, Oxford, Clarendon. [ Links ]

TURNER, Jonathan H. (1984), Societal Stratification: A Theoretical Analysis, New York, Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

VEBLEN, Thorstein ((1899) 1953), The Theory of the Leisure Class, New York, New American Library. [ Links ]

VILAR, Pierre (1962), La Catalogne dans lEspagne Moderne: Recherches sur les fondements economiques des structures nationales, Paris, SEVPEN. [ Links ]

WEBER, Max ((1922) 1978), Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, Berkeley, California Press. [ Links ]

WILLIAMSON, Jeffrey G.; LINDERT, Peter H. (1980), American Inequality: A Macroeconomic History, New York, Academic. [ Links ]

WRIGHT, Erik Olin (1997), Class Counts: Comparative Studies in Class Analysis, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Notas

1 I am grateful to John Logan, Glenn Deane and Larry Raffalovich for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

2 Department of Sociology – University at Albany (New York, U.S.A.). Direct correspondence to Richard Lachmann; Department of Sociology; University at Albany; Albany, NY 12222. E-mail: RL605@albany.edu

3 Veblen does not attempt to explain the mechanisms by which wealth is passed from one generation to the next. In that way, his study remains a static picture of the leisure class rather than the dynamic sociological analysis of its reproduction and development offered by Bourdieu.

4 There is feedback between inheritance practices and fertility patterns. Wealthy parents, in the absence of primogeniture, tend to limit the number of offspring to preserve family wealth. Even in Britain, where primogeniture was combined with dowries and cash portions to ensure that younger sons could establish themselves in careers or businesses, parents limited their fertility to preserve cash for the eldest son (Stone and Stone, 1984; Howell, 1983).

5 Soltows (1989) data for the period that they cover are preferable to those of Williamson and Lindert (1980) because Soltow makes finer distinctions, separating the top and second 1/2%, the next 1% and following 3%, while Williamson and Lindert offer results only for the top 1% and top 10%. I present Williamson and Linderts data in Table Four since it offers the longest sequence (albeit from several different sources including Soltow, and therefore calculated in somewhat different ways) for the top 1% from 1774 to 1972, while Soltows data are just for the early Republic.

6 I derive mean net worth by reducing Kennickells total by the value of vehicles and houses while eliminating his deduction for the mortgages on those houses. The minimum net worth is the amount Kennickell gives in Table Ten adjusted to reflect the average reduction of 16.6% in assets for this cohort produced by my adjustment for houses and vehicles.

7 An 8% yield on $2,060,000, the average net worth of this cohort, produces $164,800, which is 3.2 times $51,400, the average income of the bottom 95% of American families in 2001. The minimum net wealth of this cohort, $1,090,000 produces 87,200 with an 8% yield, or 1.7 times $51,400.