Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Portuguese Journal of Nephrology & Hypertension

versão impressa ISSN 0872-0169

Port J Nephrol Hypert vol.33 no.4 Lisboa dez. 2019

https://doi.org/10.32932/pjnh.2020.01.052

CASE REPORT

Gemcitabine-associated thrombotic microangiopathy – a role for eculizumab?

Teresa Chuva1, Ana Ferreira2, José Maximino1, Rui Henrique3, Ana Paiva1, Alfredo Loureiro1

1 Serviço de Nefrologia do Instituto Português de Oncologia do Porto

2 Serviço de Oncologia Médica do Instituto Português de Oncologia do Porto

3 Serviço de Anatomia Patológica do Instituto Português de Oncologia do Porto

ABSTRACT

Gemcitabine‑associated thrombotic microangiopathy (gTMA) is a rare entity that is usually associated with a poor prognosis, with loss of kidney function and often death. The management of this syndrome includes discontinuation of the drug. Other approaches have been tried, with no proven efficacy and inconsistent results, such as glucocorticoids, intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma infusion and rituximab. Drug‑induced hemolytic uremic syndrome, a form of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), has shown good response to the anti‑C5 monoclonal antibody eculizumab and anecdotal cases have been reported where eculizumab improved gTMA. We present a case where a patient with gTMA on hemodialysis was treated with eculizumab, with full recovery of hematological disorders and kidney function. We suggest that clinicians be aware of gTMA as a potentially life‑threatening condition and that eculizumab should be considered as a possible first‑line agent.

Key words: thrombotic microangiopathy, eculizumab, nephrotoxicity, acute kidney injury

INTRODUCTION

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is characterized by arteriolar and capillary thrombosis due to endothelial damage and its clinical manifestations are hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and organ injury, such as kidney failure1. TMA may present as diverse syndromes2.

When it results from dysregulation of the alternative pathway of complement, it is commonly known as atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). It may be secondary to drugs or a coexisting disease, such as cancer3, and a variety of medicines have been implicated, including different antineoplasic agents4,5. Gemcitabine‑associated thrombotic microangiopathy (gTMA), although considered a rare entity, has been described in many reports since its initial use, often associated with a poor prognosis6–11. The advent of the new anti‑C5 monoclonal antibody eculizumab has brought promising results and offers a potential therapeutic option for gTMA12–14.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 54‑year‑old Caucasian woman with a synovial sarcoma of the leg was started on weekly gemcitabine (1000mg/m2 per dose) because of recurrent disease. She had pulmonary metastasis and had previously been treated with doxorubicin, ifosfamide, trabectedin and pazopanib. Her medical history was notable for rheumatoid arthritis that had been stable without medication for more than 10 years.

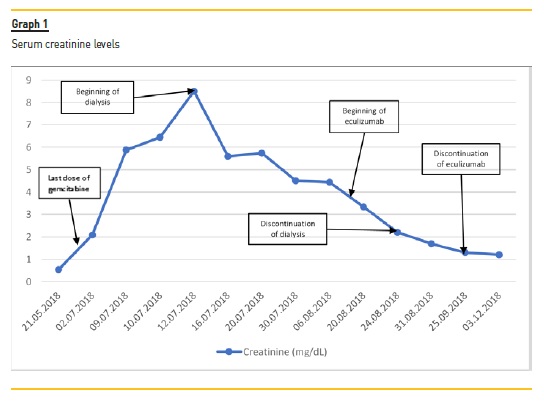

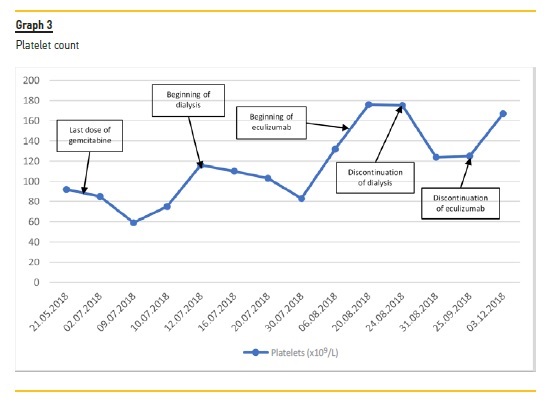

During her fourth cycle of gemcitabine (cumulative dose 15.990mg), she presented with pancytopenia that caused her to suspend treatment. Two weeks later, she developed new‑onset hypertension (blood pressure 173/101mmHg) and acute kidney injury (AKI) with serum creatinine (SCr) 2.04mg/dL (reference range 0.51–0.95mg/dL).

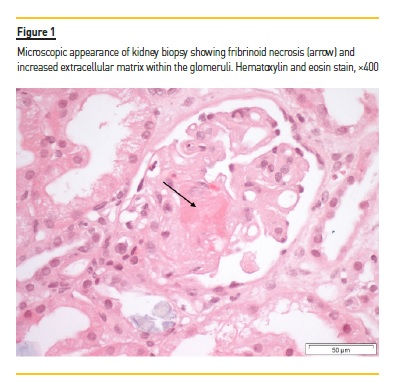

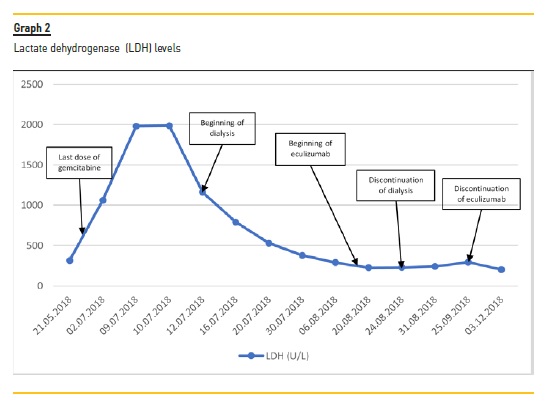

She was hospitalized after another week for hypertension, AKI, anemia and thrombocytopenia, all consistent with gTMA. Her ECOG Performance Status was 0 and she was still professionally active. The laboratory tests on admission were: SCr 5.8mg/dL; lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 1979 U/L (reference range 67–248 U/L); hemoglobin 5.8g/dL (reference range 11.5–16.5g/dL); platelets 51 x 109/L (reference range 150–400x 109/L); total bilirubin 1.6mg/dL (reference range <1mg/dL), and haptoglobin <5.83mg/dL (reference range 36‑195mg/ dL). A peripheral blood smear showed the presence of schistocytes. Coagulation tests, ADAMTS13 activity, c3 and c4 levels of the complement system were normal. CH50 and AH50 levels were not measured. Further immunologic tests were within normal ranges. Her kidney function, anemia and thrombocytopenia continued to worsen during the following days. A kidney biopsy was performed, and she was started on hemodialysis. The histologic examination showed acute tubular injury with simplified epithelium, arteriolar fibrinoid thrombosis and narrowing due to intimal edema and lamination, glomerular fibrinoid necrosis and ischemic collapse of the capillary tufts [Figure 1]. Immunofluorescence showed no glomerular or tubular staining for IgA, IgG, IgM, C3 or C1q. Genetic testing for complement mutations (CFH, CD46 [MCP], CFI, C3, THBD, CFB,CFHR5, CFHR1 CFHR3, CFHR4, DGKE) was negative.

A diagnosis of gTMA was made and gemcitabine was stopped. After the patient started hemodialysis, hemolysis markers improved, with bilirubin levels and decreasing LDH levels, but kidney function did not recover during the following weeks. Due to inconsistent results of plasmapheresis in the literature and no evidence of a circulating antibody or factor in gTMA, and after weighting potential risks and benefits, we decided against this treatment option. We agreed to start eculizumab therapy and the first dose was administered 33 days after the beginning of dialysis. The patient received 900mg every week for 4 doses, followed by 2 doses of eculizumab 1200mg at weeks 5 and 7.

Prophylaxis of meningococcal infections was made with meningococcal vaccination (Men‑ACW135Y and MenB). Although, ideally, it should be given at least 2 weeks before treatment, it was only started after the first dose of eculizumab. Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered with amoxicillin 500 mg twice daily throughout the treatment and until 60 days after the last eculizumab treatment. Other prophylaxis included the following vaccinations: Pn13, Hib and Influenza.

Her kidney function started to improve after the second dose of eculizumab and she had her last session of dialysis 10 days after the beginning of treatment. 5 months after the last hemodialysis, her creatinine was 0.96 mg/dL. Her blood pressure improved, but she continued dependent on antihypertensive drugs. At the time, she was proposed for chemotherapy with paclitaxel, but it was stopped 20 days later, after a septic episode requiring hospital admission. 10 months later, the patient died because of tumor progression. Her kidney function was normal.

DISCUSSION

gTMA is a well‑described entity that led to a boxed warning in the product labeling of gemcitabine. It was first documented by Casper et. al6 in 1994 and remains a rare but potentially lethal condition. Its incidence has been estimated to vary between 0.008% and 0.078% based on the manufacturers safety database11, yet it is possible that the reported incidence increases as clinicians become more aware of this diagnostic possibility.The mechanisms underlying gTMA have not been fully elucidated and several hypotheses have been suggested, including an immune‑associated response or a dose‑dependent direct toxic reaction with damage of the endothelial cells and activation of platelet aggregation and intravascular hemolysis2,15,16. No antibodies have been detected so far in gTMA and recent evidence17 suggests probable activation of the alternative pathway of complement, resembling the pathophysiology of aHUS. The onset is usually gradual after a median cumulative dose of 22 g/m2 (range 4–81 g/m2) given over 7.5 months (range 2–34 months)18. In our patient, both the cumulative dose and time interval until gTMA were within this range. Other reports also describe new‑onset or worsening hypertension preceding the diagnosis of gTMA7,17, which we could also observe in this case.

The beginning of treatment depends on the recognition of TMA. Although usually mild and transitory, gemcitabine is associated with myelosuppression19,20, which may delay the diagnosis. With our patient, other laboratory signs of hemolysis (elevated LDH, schistocytes, low haptoglobin, hiperbilirrubinemia) contributed to the diagnosis of TMA and a kidney biopsy additionally helped with the differential diagnosis. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura was excluded based on normal levels of ADAMTS13. Normal coagulation studies made disseminated intravascular coagulation an unlikely diagnosis.

Once gTMA was established, gemcitabine was discontinued, as recommended. Support therapy such as dialysis should be given if necessary. Further treatment strategies have varied over the years8.

Glucocorticoids, intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma infusion and rituximab have been used, with no proven benefit and inconsistent results16,21–24. Eculizumab is a monoclonal antibody directed against C5 complement protein that has been approved for aHUS25. Previous case reports have suggested that it is also effective in gTMA12,13,26 and some patients were even able to restart gemcitabine without further complications17,21. Our patient showed significant improvement with eculizumab therapy, which was started after one month of hemodialysis. It allowed for the discontinuation of dialysis 10 days after the first dose, eventually leading to a complete recovery of kidney function. The duration of treatment has also been a matter of debate27.

Since genetic studies were normal and the offending drug had been suspended, we decided to stop eculizumab after 4 initial induction doses plus another 2 for maintenance therapy, with no further occurrences.

The same limited treatment time had also been tried by other authors with successful results12. The financial burden of eculizumab should be taken into consideration when treating an oncological patient. Despite having a cancer with a bad prognosis, our patient had an ECOG Performance Status of 0 and still had other possible treatment options available, which weighed on our decision. She lived for another 15 months after stopping dialysis. The quality of life of those months was highly improved thanks to the recovery of her kidney function after eculizumab.

Despite the promising results with eculizumab in gTMA, other authors describe less favorable outcomes28. However, these also depend on the evolution of the underlying malignant disease and its possible complications, which should not be underestimated and may interfere with any positive results. More studies are needed to definitely access the benefit of eculizumab in gTMA, its indications and treatment duration.

CONCLUSION

gTMA is a rare event that often leads to the loss of kidney function and has potentially lethal consequences. Treatment options have varied over time, with inconsistent results. Although further studies are needed to validate this strategy, eculizumab should be considered as a possible first‑line therapy.

References

1. Wild A, Holasová J. Thrombotic microangiopathies. Lek Obz 2018;67:343–50. [ Links ]

2. George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med 2014;7:654–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1312353. [ Links ]

3. Sakari Jokiranta T. HUS and atypical HUS. Blood 2017;129:2847–56. doi: 10.1182/blood‑2016–11. [ Links ]

4. Pisoni R, Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G. Drug‑induced thrombotic microangiopathy. Drug Saf 2001;24:491–501. doi: 10.2165/00002018‑200124070‑00002. [ Links ]

5. Dlott JS, Danielson CFM, Blue‑Hnidy DE, McCarthy LJ. Drug‑induced thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome: a concise review. Ther Apher Dial 2004;8:102–11. [ Links ]

6. Casper ES, Green MR, Kelsen DP, Heelan RT, Brown TD, Flombaum CD, et al. Phase II trial of gemcitabine (2,2‑difluorodeoxycytidine) in patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Invest New Drugs 1994;12:29–34. [ Links ]

7. Humphreys BD, Sharman JP, Henderson JM, Clark JW, Marks PW, Rennke HG, et al. Gemcitabine‑associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Cancer 2004;100:2664–70. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20290. [ Links ]

8. Zupancic M, Shah PC, Shah‑Khan F, Nagendra S. Gemcitabine‑associated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:634–41. doi: 10.1016/S1470‑2045(07)70203‑6. [ Links ]

9. Müller S, Schütt P, Bojko P, Nowrousian MR, Hense J, Seeber S, et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome following prolonged gemcitabine therapy: report of four cases from a single institution. Ann Hematol 2005;84:110–4. doi: 10.1007/s00277‑004‑0938‑8. [ Links ]

10. Desramé J, Duvic C, Bredin C, Béchade D, Artru P, Brézault C, et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome as a complication of gemcitabine treatment : report of six cases and review of the literature. La Rev Médecine Interne 2005;26:179–88. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2004.11.016. [ Links ]

11. Fung MC, Storniolo AM, Nguyen B, Arning M, Brookfield W, Vigil J. A review of hemolytic uremic syndrome in patients treated with gemcitabine therapy. Cancer 1999;85:2023–32. [ Links ]

12. Al Ustwani Omar, Lohr James, Dy Grace, LeVea Charles, Coonoly Gregory, Arora Pradeep IR. Eulizumab therapy for gemcitabine induced hemolytic uremic syndrome: case series and concise review. J Gastrointest Oncol 2014;5:30–3. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078‑6891.2013.042. [ Links ]

13. Krishnappa V, Gupta M, Shah H, Das A, Tanphaichitr N, Novak R, et al. The use of eculizumab in gemcitabine induced thrombotic microangiopathy. BMC Nephrol 2018;19. doi:10.1186/s12882‑018‑0812‑x. [ Links ]

14. Grall M, Provôt F, Coindre J‑P, Pouteil‑Noble C, Guerrot D, Benhamou Y, et al. Efficacy of Eculizumab in Gemcitabine‑Induced Thrombotic Microangiopathy: Experience of the french thrombotic microangiopathies reference centre. Blood 2016;128:136–136. doi: 10.1182/blood.v128.22.136.136. [ Links ]

15. Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, Greenbaum LA, Babu S, Bedrosian C, et al. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic‑uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2169–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208981. [ Links ]

16. Al‑Nouri ZL, Reese JA, Terrell DR, Vesely SK, George JN. Brief Report Drug‑induced thrombotic microangiopathy: a systematic review of published reports. Blood 2015;125:616–8. doi: 10.1182/blood. [ Links ]

17. Turner JL, Reardon J, Bekaii‑Saab T, Cataland SR, Arango MJ. Gemcitabine‑associated thrombotic microangiopathy: response to complement inhibition and reinitiation of gemcitabine. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2017;16:e119–22. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2016.09.004. [ Links ]

18. Glezerman I, Kris MG, Miller V, Seshan S, Flombaum CD. Gemcitabine nephrotoxicity and hemolytic uremic syndrome: report of 29 cases from a single institution. Clin Nephrol 2009;71:130–9. [ Links ]

19. Aapro MS, Martin C, Hatty S. Gemcitabine–a safety review. Anticancer Drugs 1998;9:191–201. [ Links ]

20. Tonato M, Mosconi AM, Martin C. Safety profile of gemcitabine. Anticancer Drugs 1995;6 Suppl 6:27–32. [ Links ]

21. Rubio MEL, Martínez RR, Illescas ML, Bosch EM, Díaz MM, Inesta L de la V, et al. Gemcitabine‑induced hemolytic‑uremic syndrome treated with eculizumab or plasmapheresis: two case reports. Clin Nephrol 2017;87:100–6. doi: 10.5414/CN108838. [ Links ]

22. Izzedine H, Isnard‑Bagnis C, Launay‑Vacher V, Mercadal L, Tostivint I, Rixe O, et al. Gemcitabine‑induced thrombotic microangiopathy: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006;21:3038–45. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl507. [ Links ]

23. Lai‑tiong F, Duval Y, Krabansky F, Florence Lai‑Tiong M, Godinot J. Gemcitabine‑associated thrombotic microangiopathy in a patient with lung cancer: A case report. Oncol Lett 2017;13:1201–3. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5576. [ Links ]

24. Gourley BL, Mesa H, Gupta P. Rapid and complete resolution of chemotherapy‑induced thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome (TTP/HUS) with rituximab. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2010;65:1001–4. doi: 10.1007/s00280‑010‑1258‑4. [ Links ]

25. Soliris – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) – (eMC) n.d. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/19966/SPC/soliris (accessed May 25, 2019). [ Links ]

26. American Society of Hematology M, Provôt F, Coindre J‑P, Pouteil‑Noble C, Guerrot D, Benhamou Y, et al. Efficacy of eculizumab in gemcitabine‑induced thrombotic microangiopathy: experience of the french thrombotic microangiopathies reference centre. Blood 2016;128:136–136.

27. Wijnsma KL, Duineveld C, Wetzels JFM, van de Kar NCAJ. Eculizumab in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: strategies toward restrictive use. Pediatr Nephrol 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00467‑018‑4091‑3. [ Links ]

28. Karkowsky R, Parikh K. Eculizumab for Gemcitabine‑induced hemolytic uremic syndrome: a novel therapy for an emerging condition. Med Forum n.d.;16:2015. doi: 10.29046/TMF.016.1.007. [ Links ]

Teresa Chuva

Nephrology Department, Instituto Português de Oncologia do Porto

E‑mail: m.teresa.chuva@gmail.com

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: none declared

Received for publication: Oct 16, 2019

Accepted in revised form: Nov 27, 2019