Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista Portuguesa de Saúde Pública

Print version ISSN 0870-9025

Rev. Port. Sau. Pub. vol.31 no.1 Lisboa Jan. 2013

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsp.2013.01.001

ARTIGOS ORIGINAIS

The planning system and fast food outlets in London: lessons for health promotion practice

O sistema de planeamento dos outlets de fast food em Londres: lições para a prática da promoção da saúde

Martin Carahera*, Eileen O'Keefeb, Sue Lloyda, Tim Madelinc

aCity University London, London, United Kingdom

bLondon Metropolitan University and University College London, London, United Kingdom

cNHS Tower Hamlets, London, United Kingdom

ABSTRACT

This article considers how health promotion can use planning as a tool to enhance healthy eating choices. It draws on research in relation to the availability and concentration of fast food outlets in a London borough. Current public health policy is confining planning to local settings within a narrow framework drawing on discourses from social psychology and libertarian economics. Policy is focusing on behaviour change, voluntary agreements and devolution of the public health function to local authorities. Such a framework presents barriers to effective equity–based health promotion. A social determinant–based health promotion strategy would be consistent with a national regulatory infrastructure supporting planning.

Keywords: Planning. Fast food. Local environments. Health promotion. Local involvement. Public health.

RESUMO

Este o artigo aborda o modo como a promoção da saúde pode usar o planeamento como uma ferramenta para se comer de modo mais saudável. A pesquisa centra–se na disponibilidade e na concentração de outlets de fast food em Londres. A política pública de saúde limita o planeamento às estruturas locais, dentro de um desenho teórico estreito que vai desde a psicologia social à economia liberal. A política está centrada na mudança do comportamento, nos acordos voluntários e na devolução da função saúde pública às autoridades locais. Tal estrutura apresenta barreiras a uma eficaz promoção da saúde baseada na equidade. Uma estratégia apoiada nos determinantes sociais seria consistente com um planeamento de apoio à infraestrutura reguladora nacional.

Palavras-chave: Planeamento. Fast food. Ambientes locais. Promoção da saúde. Participação local. Saúde pública.

Introduction and background

There is an extensive public health literature outlining problems of access to affordable healthy foods for many, especially low-income, households in England. The development of what has been called the obesogenic environment, favours the unhealthy choice.1, 2 It requires multi-disciplinary understanding to make sense of complexity of the system and thus to design and implement effective policy across these levels. Problems of the obesogenic environment are amenable to being addressed by public health and planning law.3, 4, 5

Public health has a long tradition of using planning as a tool for change,6 yet in recent times this has been neglected echoing the claim of Ridde and Cloos7 that the link between health promotion and political science has been lost; and that while health promotion is essentially a political act wishing to address inequalities it fails to use social science to understand the world that it seeks to change. Much literature on access to healthy food highlights the ubiquitous nature of fast food outlets in local environments and the problematic nutritional status of the food served from them. Few, however, deal with the planning system as a means of addressing the issue, opting for description of the problem and often locating solutions in changing menu planning and individual behaviour choice.8

Calls for regulation, often elicit cries of the nanny state. In light of this response it is important to emphasise the use of planning as a means of involving local people in shaping their local food environment as well as its function in pursuit of healthy outcomes. Notwithstanding wide consensus within the public health community in understanding the obesity epidemic current government policy in England focuses on voluntary undertakings9 by the private sector food industry to improve their products, and interventions informed by social psychology and behavioural economics to provide incentives for communities, families and individuals to adopt healthier behaviour.10

Concerns about the unregulated nature of fast food outlets in the UK have led to a call at the United Kingdom Public Health Association Annual Forum 2009 from The Food & Nutrition special interest group that they would work to embed in planning processes the ability of local communities to grow, sell and buy locally produced food. Local authorities should use their restrictive powers (by-laws) to create these opportunities by restricting fast food outlets and supermarkets. Given the focus on health promotion there is a need to address issues of local power and how this can be incorporated into any initiative that might be labelled paternalistic in directing people towards certain types of behaviours.

Health promotion in respect of such a complex system must ensure that the focus goes beyond an emphasis on behaviour to one which helps create supportive and health enhancing environments. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion says that Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve their health11, 12; our contention is that this can be done by involving planners, public health professionals and the public in decisions about the local food environment backed up by regulatory mandates at supra-local levels This is consistent with the robust update of the Ottawa Charter approach found in the World Health Organization's evidence-rich Commission on the Social Determinants of Health which called for a strategy to:

Reinforce the primary role of the state in the regulation of goods with a major impact on health such as tobacco, alcohol, and food.13

This article considers the position of planning within a health promotion strategy taking the obesogenic environment seriously. A case study approach is used and it draws on research on fast food outlets (FFOs) in Tower Hamlets, a London Borough. The context for this case study is that in the United Kingdom at a time when many high street retail shops are facing closure, one area of growth is the fast food sector. The predictions are that low-income groups will eat out more from fast food outlets seeking a bargain, and there is an opportunity for more business by attracting middle-income price conscious lunchtime consumers.14

Existing research on fast food and local environments

Links have been drawn between obesity and fast-food by researchers such as Popkin.15 Links include the composition of food and drink but also issues such as choice, price and portion size.16 Some studies have found a concentration of FFOs in deprived areas and an area effect on food choice and consumption.17, 18, 19, 20 A report on high street take-aways in England showed that food from such outlets was often high in fat, salt, and sugar making healthy choices hard, even for those wishing to make healthy choices.21 For example, a KFC meal of a tower burger, regular BBQ beans, yoghourt and cola provided 97 per cent of the guideline daily amount of salt and 69 per cent of sugar.21 A 2009 consumer group report highlighted similar findings with a quarter of children reporting eating at a fast outlet in the last week and consuming too much fat, salt and sugar and opting for adult sized portions.22

Without access to shops offering a wide variety of affordable, healthy and culturally acceptable food, poor and minority communities may not have equitable access to the variety of healthy food choices available to non-minority and wealthy communities.23, 24 Members of low-income households are more likely to have patterns of food and nutrient intake that contribute to poor health outcomes.25 National data from the low-income diet and nutrition survey found that low-income families are more likely to consume high fat processed meals or fast-foods and snack foods.26 The above applies also to children and younger adults who spend a large proportion of their pocket money on food. In 2005 children reported spending £1.01 on the way to school and 74p on the way home largely on the 3Cs of confectionary, chocolate and carbonated drinks.27 This equates to £549 million per annum. Meals and snacks eaten outside the home account for about 40 per cent of calories.28 Fast-foods have an extremely high energy density and humans have a weak innate ability to recognise foods with a high energy density and to appropriately regulate the amount of food eaten in order to maintain energy balance. This produces what has been termed passive over-consumption.29 A key point about eating food from fast-food outlets is that you do not have control over the content of such food.

The research findings on the location and concentration of fast food and retail outlets differs from area to area and depends on the type of outlet and quality and range of food on sale.30 A large number and concentrations of fast food outlets can blight an area in several ways. For example, objections to concentrations of fast food outlets can be as much to do with crime and disorder as health and nutrition. Location in an area can often be more to do with passing trade, land prices, parking facilities and travel routes than with serving the local community31. Work in London shows that the situation differs from area to area and highlights the need for local assessment and local practice informed by evidence and local circumstances.32 Nevertheless, the most recent evidence indicates that the geographical distribution of fast food outlets varies with degrees of deprivation.33

Research in the UK shows that fast food outlets can be found clustered around schools,34, 35 but little work has been carried out on the solutions to this problem or how to prevent it. The high energy density of fast-food, and the impact on burden of disease associated with this, was emphasised in the Foresight Report Tackling Obesities.1 A more recent report on fast food reported that in policy terms the sector is nearly invisible – taken for granted, yet under the radar of official appraisal and public debate. (p. 3).36 The official response to the situation has largely been on education, information and labelling. All of these represent down-stream responses and still locate activity in the realm of the individual or family. These are of course necessary activities and part of the overall approach but they are insufficient to address the ubiquitous nature of such outlets on the high street or near people's homes. This picture presents reasons for considering the use of the planning system as a component of health promotion.

Case study of the fast food landscape in tower hamlets

Below is presented in some detail a case study from one London borough, Tower Hamlets, which has developed and introduced its own supplemental or extra guidance.37, 38, 39 A case study approach has been adopted40 to present findings that offer lessons for using the planning system and which allows questions to be asked about the approach of planning and its fit with public health and health promotion activities. In what follows, the case study is based on various strands of work carried out in a London Local Authority, Tower Hamlets. The case study:

provides an overview of the fast food landscape in the authority;

outlines how evidence-based policy was developed in the authority with stakeholders to address problems of unhealthy takeaways;

considers how that policy provides space for planning as a component of health promotion at the local level.

The Tower Hamlets work along with that in the ObesCities report comparing obesity prevention strategies in New York and London41 has spurred a number of local authorities across the UK into taking action. All the data unless otherwise stated comes from two studies.41 The detail of the methodology such as mapping, focus groups, observational studies, food sampling and policy analysis have not been presented here but can be found in the reports and articles referenced.37, 38, 39

Background to the study area

The borough of Tower Hamlets is one of the 33 London Boroughs with a population estimated at 232,000.42 The borough has a long history of migration from the early 1600s onwards with various waves of French, Irish, Afro-Caribbean and, more recently, migrants from the Indian sub-continent settling there, before moving onto other areas.43 The majority of the population are from a non-white British background, with the largest minority ethnic group (34 per cent) being Bangladeshi with half of this community third generation – born locally. Mortality rates in the borough are high from heart disease, and cancers and respiratory disease are highest or second highest when compared to other London boroughs. In comparison with England norms these are the biggest contributors to inequalities in life expectancy between Tower Hamlets and other English local authorities.44 Only 15 per cent of eleven, thirteen, and fifteen year old pupils in the borough eat 5 or more portions of fruit and vegetables compared to the national figure of 23 per cent. Fifteen per cent of four to five year old children are obese and this increases to 23 per cent for 11 year olds; it is the most deprived borough for income deprivation affecting children.45 A 2009 health and lifestyle survey in Tower Hamlets found among 16 year olds high use of fast-food take-aways and low levels of consumption of recommended amounts of fruit and vegetables.46 Males report eating fast-food with a far greater frequency than females and members of ethnic minority groups such as those from a South Asian background reporting higher levels of eating out, 26.5 per cent as compared to 15.4 per cent from other backgrounds.

Findings

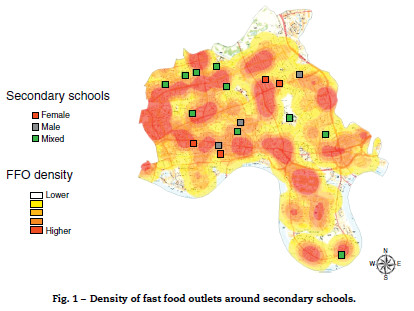

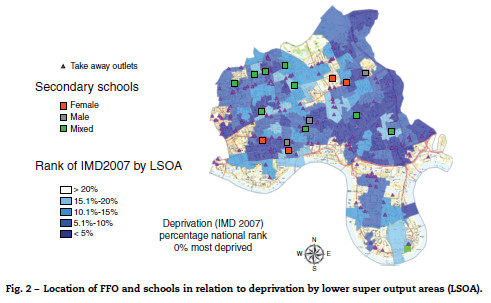

There are 2214 registered food businesses in the borough of which 297 were grocers or mini-markets and 627 were FFOs. Ninety-eight per cent of households (93,219) are within 10 min walk of a FFO. At first glance physical access to shops in Tower Hamlets would appear to be adequate with 76 per cent of households within 10 min walk of a supermarket, retail market, bakers or greengrocers. Nearly all (97 per cent) of households were within a similar distance of a grocery store, although our research indicates that many grocery stores would only carry a very limited range of healthy food. This was shown by our use of the proxy measure of the availability of five fresh fruit and seven fresh vegetables in any one shop. This should be contrasted with the finding from the mapping that 97 per cent of households are within 10 min walk of a FFO. Similarly 98 per cent of schools had six FFOs within 400 m and 15 within 800 m (see Fig. 1). Samples of the food taken from the outlets showed most to be high in fat, salt or sugar. So the choices people have are heavily weighted in favour of unhealthy ones.

The School Food Trust in 2008 published findings on the number of junk food outlets around schools in England, devising an index of schools to junk food outlets (including confectionary shops) and ranking local authorities on this basis.47 There was no separate figure for Tower Hamlets which was grouped with ten other London Boroughs to provide an index of 36.7, i.e. 37 outlets per secondary school. The national average was 23 outlets per school, with an urban average of 25 outlets per school and for London 28. Our estimates of the ratio of food outlets to secondary schools for Tower Hamlets provides a ratio of 41.8 outlets per school which compares to School Food Trust average ratio of 38.6 for the UK 10 worst areas. The debate over the role that geographic access and availability play in determining dietary outcomes has proved contentious and much of the work undertaken has not been on highly urbanised, geographically compact areas, such as Tower Hamlets.

Our findings showed concentrations of FFOs near schools and in deprived areas, using national deprivation rankings (see Fig. 2), but these concentrations did not persist when Tower Hamlets internal rankings of deprivation were used. The area of Tower Hamlets has such widespread poverty that the differences within the area are marginal whereas comparison with neighbouring boroughs shows up these inequalities. Several issues emerged. One was the clustering of FFOs; a second was the clustering of FFOs in deprived areas in the north of the borough around both schools and neighbourhoods. Sampling and analysis of food typically bought from FFOs showed that it was high in fat, saturated fat.

The qualitative and observational study support this contention.37, 38, 39 So there is a need to expand the focus from hot fast-food to what Sinclair and Winkler33 call the cold take-aways, such as the sandwich shops and grocery stores. Our own data show that the availability of these cold food outlets is high. Also while school gate policies restricting access to the high street were useful in preventing pupils from purchasing food at lunchtimes, they had no impact on stopping purchase of unhealthy products on the way to and from school.

The problems are fourfold for those living in the Borough of Tower Hamlets:

1. The lack of healthy options and the absence of any nutrition information in fast-food outlets.

2. The lack of other affordable healthy options in the local environment.

3. Large numbers of take-aways contributing to an obesogenic environment and lack of healthy choice.

4. The lack of owner awareness of the problem, along with the perceived extra costs that providing healthy food would require and a lack of customer demand.

Research informed policy development

Findings from the research sketched above was used to help inform local policy and actions in the borough. The presentation of data with a local focus brought home to many of the public health and council officials what remains an abstract argument in reports such as the WCRF global report.48 The establishment of a local advisory group was important in this respect as a key issue was to use the findings to inform processes of training support, local health promotion activities and the development of local planning policy. The research information had to be communicated in ways which were understandable and had meaning for a wide policy audience. Local data carries weight in influencing local policy development. Part of the reporting and review process involved informing the steering group of developments in other geographical areas. Key among these was the potential to develop policy for planning and regulating openings of new FFOs in the borough and for planning officials in the local authority to work with public health staff in the health agency. This has occurred following a number of council decisions and planning appeals.

The local authority continues to develop this work and has commissioned further research (see http://moderngov.towerhamlets.gov.uk/ieListDocuments.aspx?CId=320&MId=3416&Ver=4). The policy documents resulting from this work have been sent for public consultation -technically known as a Call for Representations (http://moderngov.towerhamlets.gov.uk/ieListDocuments.aspx?CId=320&MId=3416&Ver=4) and have been approved. The proposals are for restrictions on types of outlets in designated areas of the borough some of which are:

In some designated areas there will be no new openings of FFOs due to the adverse effect on the quality of life for local residents

FFOs will not be allowed to exceed five per cent of total shopping units.

There must be two non-food units between every new restaurant or take-away

The proximity of a school or local authority leisure centre can be taken into consideration in all new applications for a FFO

New FFOs will only be considered in town centres or retail areas and not in residential areas.

The attempt to link public health and planning is far from over, but the outcomes so far show what can be achieved in attempting to influence the health of an area by a focus on the upstream elements of place. As well as the planning system developments outlined above the local and health authorities supported work with existing local fast food outlets52 including:

Reviewing the Council's own commercial letting policies to promote healthier food on sale in local retail centres.

Undertaking a social marketing programme to help overcome perceived barriers to healthy eating in Tower Hamlets, including identifying healthy options.

Training for owners on raising awareness and how to produce healthy food.

The development of an awards scheme.49

This multi-pronged approach is necessary to address the existing situation and to plan for the future opening and control of new FFOs. This includes working with fast-food owners to improve the nutrition of their products as well as promote healthier options and smaller portion size as well as working with suppliers of sauces and processed meat products to change the composition of food at source or upstream.49 Many of the fast food outlets in the borough are small independent operators and owned by members of ethnic minority communities. In tackling the issues there is a need to work with these small independent operators to help them improve their food offer and not disadvantage them. There are few chain outlets in residential areas of the borough, the national and international brand chains being located central in the south of the borough, an area which has a business district. This constitutes an equalities issue as restrictions on new openings may disadvantage those small and medium scale entrepreneurs, often coming from the local community, while major chains can sit out the process and/or appeal any local regulation.

Discussion

In London the major thrust for using planning processes to control the food environment has been taken by local authorities. Some local authorities are beginning to address these issues, perhaps the most publicised being Waltham Forest, in the north east of London, taking steps to ban new outlets within 400 m of a school, and others such as Barking and Dagenham, in the east of London, developing new local supplementary guidance (http://www.healthyplaces.org.uk/case-studies/barking-dagenham/ accessed 8th Sept) as well as the proposal to introduce a £1000 levy to be used to tackle childhood obesity in the borough. So there are attempts towards health promoting development at the local level within London and indeed across England. There is no national guidance on food or fast food outlets in the local environment, therefore leaving those authorities who are interested in tackling the issue to develop their own.

In order to make the case for using planning to promote a salutogenic and weaken the obesogenic environment, it is useful to bring developments elsewhere to the attention of local decision-makers as was the case in Tower Hamlets. Providing local data on the scale of the problem brought awareness of the problem but not necessarily of the solutions. The use of public health law is well established in controlling the availability of items such as alcohol, tobacco50. Samia Mair and colleagues51 in the US examined how zoning laws might be used to restrict the opening of FFOs. Planning can employ incentives, performance or conditional zoning.52 Performance zoning takes account of the effects of land use on the local area and community. Specific ways of achieving this include banning and or restricting:

FFOs and/or drive through outlets.

Formula outlets (formula can be defined broadly to include local take-ways that have one or more outlets or narrowly to include only larger national chains).

FFOs in certain areas or by directives specifying distance from schools, hospitals.

By using quotas in certain areas either by number of shop frontage or by use of density.

Restricting opening hours.

Making the link between registration for food hygiene and licensing more explicit.

Introducing labelling in fast food outlets.

Using choice editing and specifying the nutrient content of food sold, so the choice is made before the consumer purchases.

The implementation of such restrictions may seem far fetched in England, yet Los Angeles has banned the opening of FFOs in certain areas for a year. The Los Angeles initiative is an anti-obesity measure as they found that there was a concentration of FFOs in poor areas.53 New York City is distinctive as a world city putting in place wide-ranging public health policy which includes a deliberate focus on regulatory measures as the context for health promotion.54, 55 Its planning strategy in respect of FFO has attracted attention for compulsory calorie labelling of menu items in chains having 15 or more outlets. This can assist consumers to make healthier choices, but it is crucial to see that this is set within a broad framework which shapes the food environment to ensure access to healthier food.56 Hence the New York the city-wide ban on trans-fats and requirement for nutrition standards for all public food procurement has upstream impacts on the population not just individuals able to make healthy choices. Approaches and policies not adopted or taken-up in London.

The ObesCities Report, a comparative study of policies developed in New York and London to tackle childhood obesity noted the wide-ranging and robust approach taken in New York in respect of fast food outlets.57 The first recommendation of the ObesCities Report was to use land use planning powers to control takeaways. This would include zoning and land use review, tax incentives and city owned property to shape the spatial distribution of healthier food outlets. Commenting at the report's launch, Boris Johnson, the Mayor of London, declared war on junk food firms saying that fast food exclusion zones could be set up around schools and in parts of the city with an obesity problem. He added that A superb 2012 legacy for London would be the obliteration of childhood obesity. I hope that working with New York will result in leaner, fitter, children and families in both cities. I want to take on the fast food companies who mercilessly lure children into excessive calorie consumption.58 As the Mayor is responsible for pan-London spatial planning, general planning policy, pan-London public health policy might be expected to provide a framework for improving the food environment in respect of takeaways. In Novemebr 2012 the Mayor launched a toolkit for fast food outlets. This stopped short of developing a pan-London perspective on fast food location and regulation or of recommending the development of exclusion zones around schools. Instead it offered guidance to individual boroughs to develop their own approaches to tackling the problem.59

At the time of writing the UK government are proposing changes to the planning system to make it less bureaucratic and more business friendly (http://www.communities.gov.uk/news/corporate/1871021, accessed 3rd September 2012). This has been seen by some as being sympathetic to big businesses and making it easier for them to gain permission to open outlets while cutting back on local accountability. While the existing English planning guidance for town centres does not specifically address the issue of take-aways, it does include a section on health impact assessment and food which states that [T]here will be a benefit to people on lower incomes through improved access to good quality fresh food and other local goods and services at affordable prices. This is because the new impact test will better promote consumer choice and retail diversity helping to control price inflation, improving accessibility and reducing the need to travel. Nevertheless, there is no legal requirement for planning authorities to gauge the health impact of a new business. The next section addresses whether the public health landscape provides a framework to promote healthy food environments.

The public health landscape is changing in England at national, regional and local levels, with much implementation due to come on stream from April 2013. Heralded as putting communities, families and individuals in the driving seat for policymaking, the public health function is being devolved to local authorities. This is intended to enable action on some of the social determinants of health to be brought together to promote health and wellbeing. Local policy formation is to be supported by national policy based on voluntary agreements with the food industry – The Responsibility Deal (see http://responsibilitydeal.dh.gov.uk, accessed 10th January 2013). There are no mandates to regulate through planning, but there is a proposal which has relevance to the fast food industry: a calorie reduction pledge. Actions to address this proposal might include reformulation of products to make them less energy dense, reduce portion sizes and provide calorie labelling to influence consumer choice. To date the main focus has been on retailers and not FFOs. Another issue arising from the responsibility deals is that they mainly involve large national and multi-national companies and not small independent outlets like the majority of FFOs in the Tower Hamlets case study above. Another key point to note about the Pledges and the Responsibility Deal is that they are voluntary agreements. It is recognised that the effect of voluntary agreements is limited.60 The relocation of public health to local authorities gives them an advantage in that they are closer to the planning system and could, like the early pioneers of public health, take advantage of this relocation.

The legislation for public health in England includes the establishment of a London Health Improvement Board (LHIB), to be run by the Mayor and the 33 London Local Authorities working to add value to the public health activities of those local authorities. Also it has been agreed that childhood obesity is to be one of its four priorities. With a primary focus on a Healthy Schools programme, it has proposed a set of nine key tasks, developed following workshops with stakeholders which included vigorous debate. One of the nine priority tasks through March 2014 is to Change the food environment in London to support healthier choices – working in partnership with the London Food Board and others. Components of this task include undertakings in three areas:

1. Support local authorities to use existing planning powers to restrict the opening of takeaways, especially close to schools;

2. Extend the Healthy Catering Commitments programme which provides awards to eating establishments which voluntarily meet given nutritional standards;

3. Take steps to increase the availability of fruit and vegetables in convenience stores (http://www.lhib.org.uk/attachments/article/101/2b-Child%20Obesity.pdf, accessed 14 Sept 2012).

None of the LHIB proposed work programme calls for additional pan-London or national planning powers. However, two elements of the preliminary planning may provide a basis for at least discussing the need for pan-London and national regulation:

First the development of the LHIB's vision, aims and delivery principles has included an analysis of the approach taken in New York City to tackle obesity, its impact, and the lessons London can learn. At a strategic level, this includes the need for shared vision and commitment from senior leaders and influential figures; and the development of bold proposals that stimulate debate among leaders and communities.

Second Consideration of equity issues is a core part of this work, and a health inequalities impact assessment will be developed to accompany the final workplan.

There is potential, therefore for the work of the LHIB to be open to new learning about best practice from elsewhere. In the context of the London-centric focus of politicians and the media in England, such learning might lead to useful spin-offs for other localities. Any work on take-aways and fast food needs to be set in the context of how, where and why people access food as set out in a recent report from the American Planning Association who warn of the dangers of allowing obesogenic and unhealthy situations to develop, and then expecting that health promotion or planning can tackle the problems.61

Conclusion

We contend that long-term options are best pursued though the introduction of central enabling legislation which local government authorities and local health agencies can adopt. When addressing whole system problems, such as those resulting from an obesogenic environment, local policy-making is necessary but not sufficient. Planning on its own cannot address the total problem. Other upstream interventions acting on social determinants of health employed elsewhere including taxes and subsidies provide incentives to both those running FFOs and customers.57, 62

Successive national governments in England have not put into place at the national level, social determinants informed health promotion infrastrucure that would engage speedily and effectively with unhealthy food environments. The default position consistent with the emerging public health landscape in England runs the danger of further disadvantaging the very communities most at risk.

Many public health analysts welcome empowered decision-making at the local level, which is promised in the emerging public health policy in England, in contrast with wholly top-down policy formation. Top down decision making might give little scope for shaping initiatives in line with distinctive demographic and epidemiological assessment and judgement by civil society groups and communities of practice. While existing planning legislation in London and England is weak in protecting citizens and for providing salutogenic environments, it does offer opportunities. This article has shown how in Tower Hamlets and many other localities in both London and across England there is enthusiasm to control the local food environment and that links can be made across formal public health services and local authority planning services to move towards a health promoting public health strategy. We would not want to claim success for all the activities undertaken since our work but would make some claim to this being the kickstart for a body of work ranging from activities with local owners of outlets, reformulation of foods, the training of food service staff, a registration scheme and the development of local planning guidance. The lessons from this research have been used to inform similar processes in areas such as Glasgow, Liverpool/Merseyside and Belfast.63, 64

Moves towards new and more powerful legislation related to the food environment must grasp the current potentials and limitations of the planning system. This knowledge and skill base must be shared by local politicians, planners, businesses and communities. In this context spirited impetus to support local authorities is being provided by civil society groups. For instance, The National Heart Forum, an influential civil society alliance of national organisations, has stepped in to provide background information on how to use planning. Its recent report devoted to local authorities describes the planning system, outlines how planning can be used for public health and specifies specific mechanisms and processes which can be used.65 In addition it has in 2012 set up an on-line resource, Healthy Places, to provide what has hitherto been very difficult to access, a compendium of successful case studies (see http://www.healthyplaces.org.uk/key-issues/hot-food-takeaways/development-control/).

While legislative systems differ, the US experience merits further consideration in the context of English planning laws. The initiatives in New York City as well as being anti-obesity measures are also designed to address the issue of widening inequalities. It is notable that while New York adopts informational behaviour change initiatives as in the case of calorie labelling, this is within a policy portfolio with a strong presence of regulation. This approach has been credited with NY City's life expectancy rising faster than anywhere else in the USA and attributed to the city's aggressive efforts to reshape New York's social environment a movement led by the city's public health department with forceful backing from its Mayor.66

Bibliografía

1. Foresight. Tackling obesities: future choices?project report. London: The Stationery Office; 2007. [ Links ]

2. Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, McPherson K, Finegood TD, Moodie ML, et–al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011; 378:804–14. [ Links ]

3. Dietz WH, Benken DE, Hunter AS. Public health law and the prevention and control of obesity. Milbank Quart. 2009; 87:215–27. [ Links ]

4. Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Quart. 2009; 87:123–54. [ Links ]

5. Mello M. New York city''s war on fat. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:2015–20. [ Links ]

6. Finer SE. The life and times of Sir Edwin Chadwick. London: Methuen and Co; 1952. [ Links ]

7. Ridde V, Cloos P. Health promotion, power and political science. Global Health Promot. 2011; 18:03–4. [ Links ]

8. Rayner G, Lang T. Is nudge an effective public health strategy to tackle obesity?. No. Br Med J. 2011; 342:d2177. (Clinical Research Ed. [ Links ]).

9. Department of Health. The public health responsibility deal. 2011. Available at: http://responsibilitydeal.dh.gov.uk/ [accessed 10.09.12]. [ Links ]

10. Sunstein C, Thaler R. Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale: Yale University Press; 2008. [ Links ]

11. World Health Organization. The Ottawa Charter. Geneva: WHO; 1986. [ Links ]

12. Nutbeam D. Health promotion glossary. Geneva: WHO; 1998. [ Links ]

13. World Health Organization. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: WHO; 2008. p. 16. [ Links ]

14. McDonalds and Allegra Strategies. Eating out in the UK 2009: a comprehensive analysis of the informal eating out market. London: Allegra; 2009. [ Links ]

15. Popkin B. The world is fat: the fads, trends, policies and products that are fattening the human race. New York: Avery; 2009. [ Links ]

16. Lin BH, Guthrie J. The quality of children''s diets at and away from home. Food Rev USDA. 1996; May?August:45–50. Economic Research Service. [ Links ]

17. Macdonald L, Cummins S, Macintyre S. Neighbourhod fast–food environment and area deprivation–substitution or concentration?. Appetite. 2007; 49:251–4. [ Links ]

18. Reidpath DD, Burns C, Garrard J, Mahoney M, Townsend M. An ecological study of the relationship between social and environmental determinants of obesity. Health Place. 2002; 2:141–5. [ Links ]

19. Kavanagh A, Thornton L, Tattam A, Thomas L, Jolley D, Turrel G. VicLANES: place does matter for your health. Melbourne: University of Melbourne; 2007. [ Links ]

20. Kwate NAO. Fried chicken and fresh apples: racial segregation as a fundamental cause of fast–food density in black neighborhoods. Health Place. 2008; 14:32–44. [ Links ]

21. National Consumer Council. Takeaway health: how takeaway restaurants can affect your chances of a healthy diet. London: National Consumer Council; 2008. [ Links ]

22. Which? Fast food: do you know what our kids are eating? Which?. 2009. October, p. 66–8. [ Links ]

23. Burns C, Inglis AD. Measuring food access in Melbourne: access to healthy and fast–foods by car, bus and foot in an urban municipality in Melbourne. Health Place. 2007; 13:877–85. [ Links ]

24. Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, Poole C. Neighbourhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002; 22:23–9. [ Links ]

25. Dowler E. Policy initiatives to address low–income households? nutritional needs in the UK. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008; 67:289–300. [ Links ]

26. Nelson M, Erens B, Bates B, Church S, Boshier T. Low income diet and nutrition survey. London: Food Standards Agency; 2007. [ Links ]

27. Sodexho. The Sodexho school meals and lifestyle survey 2005: Whyteleafe. Surrey: Sodexho; 2005. [ Links ]

28. Henderson L, Gregory J, Swan G. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: adults aged 19 to 64 years: volume 1: types and quantities of foods consumed. London: TSO; 2002. [ Links ]

29. Prentice AM, Jebb SA. Fast–foods, energy density and obesity: a possible mechanistic link. Obes Rev. 2003; 4:187–94. [ Links ]

30. Coun S. Deprivation amplification revisited: or, is it always true that poorer places have poorer access to resources for healthy diets and physical activity?. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2007; 4:32. [ Links ]

31. Melaniphy J. The restaurant location guidebook, a comprehensive guide to picking restaurant and quick service food locations. Chicago: International Real Estate Location Institute Inc; 2007. [ Links ]

32. Bowyer S, Caraher M, Eilbert K, Carr–Hill R. Shopping for food: lessons from a London borough. Br Food J. 2009; 111:452–74. [ Links ]

33. Sinclair S, Winkler JT. The School Fringe: what pupils buy and eat from shops surrounding secondary schools. London: Nutrition Policy Unit, London Metropolitan University; 2008. [ Links ]

34. Austin SB, Melly SJ, Sanchez BN, Patel A, Buka S, Gortmaker SL. Clustering of fast–food restaurants around schools: a novel application of spatial statistics to the study of food environments. Am J Public Health. 2005; 95:1575–81. [ Links ]

35. Day PL, Pearce JR. Obesity–promoting food environments and the spatial clustering of food outlets around schools. Am J Prev Med. 2011; 40:113–21. [ Links ]

36. New Economics Foundation. An inconvenient sandwich: the throwaway economics of takeaway food. London: New Economics Foundation; 2010. [ Links ]

37. Caraher M, Lloyd S, Madelin T. The ?school Foodshed?: schools and fast–food outlets in a London borough. Br Food J. 2013. DOI information unavailable. [ Links ]

38. Lloyd S, Caraher M, Madelin T. Fish and chips with a side order of trans fat: the nutrition implications of eating from fast–food outlets: a report on eating out in East London. London: Centre for Food Policy, City University; 2010. [ Links ]

39. Lloyd S, Madelin T, Caraher M. Report on fast food outlets (FFOs) in Tower Hamlets: a borough perspective. London: Centre for Food Policy, City University; 2008. [ Links ]

40. Thomas G. How to do your case study: a guide for students and researchers. London: Sage; 2010. [ Links ]

41. City University of New York , London Metropolitan University. A tale of two ObesCities comparing responses to childhood obesity in London and New York City. 2010. [ Links ]

42. Greater London Authority. Round population projection PLP low. London: GLA; 2007. [ Links ]

43. Dench G, Gavron K, Young M. The New East end: kinship, race and conflict. London: Profile Books; 2006. [ Links ]

44. Tower Hamlets PCT. Annual public health report. London: Tower Hamlets PCT; 2007. [ Links ]

45. OFSTED Tellus2 Survey; 2007. http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/ [accessed 26.07.08]. [ Links ]

46. Ipsos MORI. Face to face random probability survey of 2342 respondents aged 16 and over carried out in Tower Hamlets on behalf of the local NHS trust. London: Ipsos MORI; 2009. [ Links ]

47. School Food Trust. Junk food temptation towns index. London: School Foods Trust; 2008. [ Links ]

48. American Institute for Cancer Research. World activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global, perspective. Washington: Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007. [ Links ]

49. Sandelson M. Tower Hamlets Food for Health Award Project March 2009?March 2012. London: Tower Hamlets Public Health Directorate; 2012. [ Links ]

50. Brownell K, Warner K. The perils of ignoring history: big tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is big food?. Milbank Quart. 2009; 87:259–94. [ Links ]

51. Samia Mair J, Pierce M, Teret S. The use of zoning to restrict fast food outlets: a potential strategy to combat obesity. USA: The Center for Law and the Public''s Health at Georgetown and Johns Hopkins Universities; 2005. [ Links ]

52. Samia Mair J, Pierce MW, Teret SP. The use of zoning to restrict fast food outlets: a potential strategy to combat obesity. The Centre for Law and Public Health, Johns Hopkins University; 2005. [ Links ]

53. Reuters Los Angles. City Council passes fast food ban. Available on http://www.reuters.com/article/healthNews/idUSCOL06846020080730 [accessed 29.08.08].

54. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Healthy heart avoid trans fat. Available on http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/cardio/cardio–transfat.shtml [accessed 29.08.08]. [ Links ]

55. Dinour L, Fuentes L, Freudenberg N. Reversing obesity in New York City: an action plan for reducing the promotion and accessibility of unhealthy food. New York: City University of New York Campaign against Diabetes and the Public Health Association of New York City; 2009. [ Links ]

56. Ashe M, Jernigan D, Kline R, Galaz R. Land use planning and the control of alcohol, tobacco, firearms and fast food restaurants. Am J Public Health. 2003; 93:1404–8. [ Links ]

57. Freudenberg N, Libman K, O?Keefe E. A tale of two ObesCities: the role of municipal governance in reducing childhood obesity in New York and London. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2010. [ Links ]

58. Crerar P. Grow your own school dinners to beat obesity, says Boris Johnson. Eveing Standard. 2010. 25th January. Available on http://www.standard.co.uk/news/grow–your–own–school–dinners–to–beat–obesity–says–boris–johnson–6710610.html [accessed 10.01.13]. [ Links ]

59. The Mayor of London. Takeaways toolkit: tools, interventions and case studies to help local authorities develop a response to the health impacts of fast food takeaways. London: The Greater London Authority; 2012. [ Links ]

60. Sharma L, Teret S, Brownell K. The food industry and self–regulation: standards to promote success and to avoid public health failures. Am J Public Health. 2010; 100:240–6. [ Links ]

61. Hodgson K. Planning for food access and community–based food system. US: American Planning Association; 2012. [ Links ]

62. Mytton OT, Clarke D, Rayner M. Taxing unhealthy food and drinks to improve health. BMJ. 2012; 344:e2931. [ Links ]

63. Glasgow Centre for Population Health. Are school lunchtime stay–on–site policies sustainable? A follow–up study. Briefing paper 33. Glasgow Centre for Population Health: Glasgow; 2012. [ Links ]

64. Stevenson L. Practical strategies to improve the nutritional quality of take–away foods. Presentation at Heart of Merseyside conference 'Takeaways Unwrapped' Developing Local Policy: healthier food and the 'informal eating out' sector. Thursday 7th April 2011. 2011. [ Links ]

65. Mitchell C, Cowburn G, Foster C. Assessing the options for local authorities to use the regulatory environment to reduce obesity. London: The National Heart Forum; 2011. [ Links ]

66. Alcorn T. Redefining public health in New York City. Lancet. 2012; 379:2037–8. [ Links ]

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Received 18 September 2012. Accepted 21 January 2013

*Corresponding author: m.caraher@city.ac.uk