Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Psicológica

versão impressa ISSN 0870-8231versão On-line ISSN 1646-6020

Aná. Psicológica vol.38 no.1 Lisboa mar. 2020

https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1675

Can we count on each other? An inquiry about Portuguese citizens’ individual and relational dispositions

Podemos contar uns com os outros? Uma investigação sobre as disposições individuais e relacionais de cidadãos portugueses

Maria Minas1

1Faculdade de Psicologia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal

ABSTRACT

Every human being has the capacity to contribute to collective well-being. The purpose of this article is to understand the dispositions and perceptions of a group of Portuguese citizens, regarding their relationships with others and their satisfaction with life, having into consideration the differences according to the socio-economic level and sex. This article presents a quantitative study involving an analysis of the 1187 Portuguese citizens’ responses to an online questionnaire aimed at analyzing their satisfaction with life (SLS), sense of community (BSCS), perceived social support (SPS), social comparison (SCS), competition (SAIS), external shame (OASS) and willingness to contribute (WCS) of members of the Portuguese society, whilst understanding the influence of sociodemographic characteristics such as sex and socio-economic situation. Crossing the values assigned to Competition and socio-economic situation (Resources) four groups were created. The results showed that both the highest values for SLP, SPS, BSCS, and the lowest values for OASS, were predominantly concentrated in the Low Competition-High Resources Group. By contrast, the lowest values for SLS, SPS, and the highest values in OASS were predominantly concentrated in the High Competition-Low Resources Group. In respect to WCS, the lowest values were concentrated at the High Competition groups and the highest values at the Low Competition groups. No statistical differences were found for SCS between groups. These results suggest that the focus on collective values of mutual trust are associated with greatest satisfaction with life, social support and willingness to contribute, involving less need for competition and defensiveness.

Key words: Portuguese citizen well-being, Quantitative analysis, Online questionnaire.

RESUMO

Todos os seres humanos têm a capacidade de contribuir para o bem-estar coletivo. Este artigo apresenta um estudo quantitativo que envolveu a análise das respostas de 1187 cidadãos portugueses a um questionário online, com o objetivo de analisar a sua satisfação com a vida (SLS), sentido de comunidade (BSCS), apoio social percebido (SPS), comparação social (SCS), competição (SAIS), vergonha externa (OASS) e desejo de contribuir (WCS), tendo em conta a influência de fatores sociodemográficos como o sexo e a situação económica. Através da criação de grupos, cruzando os valores respeitantes à Competição e aos Recursos, os valores mais altos nas variáveis globais de SLP, SPS, BSCS e os valores mais baixos nas variáveis globais de OASS concentraram-se predominantemente no grupo alta competição, baixos recursos. Relativamente à escala WCS, os valores mais baixos concentraram-se nos grupos de alta competição e os valores mais altos nos grupos de baixa competição. Não foram encontradas diferenças significativas entre os grupos na variável global SCS. Estes resultados sugerem que o foco em valores coletivos de confiança mútua estão associados a uma maior satisfação, apoio social e desejo de contribuir, envolvendo uma menor necessidade para competir e assumir posturas de defensividade.

Palavras-chave: Bem-estar dos cidadãos português, Análise quantitativa, Questionário online.

The development of healthy relationships has been recognized as crucial for human and social life. Nonetheless, many social environments are marked by segregation, prejudices and mental health problems, which have a large impact on individuals and the society (Tacket et al., 2009). Individuality and relationships are shaped in a socioeconomic context (Waldegrave, 2009). There is no doubt that the economic paradigms of modern economies have brought progress, positively affecting the lives of billions of people. Nevertheless, not all benefit from such development: 94% of the world income is distributed to 40% of the population, while the other 60% of the people are left to live with only 6% of the total income (Yunus, 2009). The economic crisis is also affecting many countries worldwide. In Portugal, the economic instability is compelling. It is affecting internal and external levels of trust and having a direct impact on civil livelihood (European Commission, 2009). The OECD Better Life Index (2012), noted a significative gap between the richest and the poorest in Portugal. In gereral, 86% of the Portuguese citizens perceive that they have someone they could count on if they needed. However, this percentage dropped when observing Portuguese people with a low degree of education separately (80%).

In a time where, for the Portuguese and in the broader context of Europe, the world economic crisis is front and centre, some important questions emerge: How are Portuguese people being affected and coping with these challenges? Which dispositions and interactional dynamics are the Portuguese adopting? Which of those dynamics are protective and potentiate well-being, and which are threatening it?

This article presents a quantitative study that aimed to understand the shape of Portuguese citizens’ individual perceptions and relational dynamics, considering nine variables: satisfaction with life, sense of community, social support, social comparison, external shame, competition, willingness to contribute and two socio-demographic factors (resourses and sex). The authors also aimed to take the first steps in the creation of a Willingness to Contribute Scale. The study is part of a broad research project that involves mixed methods, with the overall goal of identifying best practices and strategies for poverty reduction and to promote individual and collective well-being (Minas, Ribeiro, & Anglin, 2018).

The article is organized according to the following structure: literature review, methodology, presentation of findings, discussion and integration of the literature, and conclusion with implications for further research and practice.

Literature review

Individual and collective dispositions

The dichotomy between individual and collective motivations has long been a puzzle for social sciences and a great challenge to interpersonal relationships (Klapwijk & Van Lange, 2009; Simpson & Willer, 2007). Van Lange (2000) associates prosocial motivations with cooperation, equality and generosity and pro-self motivations with individualism and competition, suggesting that in different contexts certain ones can be more adaptative than others. Adam Smith (1759) introduced the concept of the invisible hand, arguing that the society prospered thanks to individuals’ self interest. This theory still influences the structure of our society today. Sayago (2008), in a reflection about contemporary society, argued that relationships are mediated by the willingness to dominate or to be better than the other. Individuals struggle to gain their place in social groups, competing for acceptance and to earn a positive status (Gilbert, 1997). Most interactions are mainly driven by the goal of maximizing personal benefits (Doron & Parot, 2001). In this sense, individuals overestimate the dimension of having and underestimate the dimension of being (Sayago, 2008). Over the years, social status has strongly influenced the access to fundamental resources (Doron & Parot, 2001). Individual hierarchical positions are dear to people, perhaps because they give them the power to control one’s life and to impact relationships (Deaton, 2003). For this reason, individuals tend to strive for competitive advantage and for maximizing individual’s gains (Doron & Parot, 2001; Gilbert, 2000). Gilbert et al. (2007) observed that individuals assume one of two different stances concerning competition – insecure or secure. Individuals who assume the insecure stance strive to receive external validation and believe they need to compete to avoid inferiority. On the contrary, individuals who show a secure stance perceive they are accepted and valued by what they are, independently of their performance. The competitive behavior, then, seems related to the degree of security experienced in interpersonal relationships. Western societies are becoming more individualistic over the years (Maner & Gailliot, 2007). Nevertheless, a collectivist orientation seems to promote long-term individual and collective well-being (Van Lange, 2000). According to Bruni (2012), market relationships involve impersonal exchanges that allow individuals to satisfy their needs without needing to regard others’solidarity. The concept of the invisible hand applyed to community life is limited, since it can reinforce vertical relationships driven by self-interest and dependency, relegating closeness and mutual support to the background. Van Lange (2000) considers that individualistic dimensions, although important, are overestimated and such an orientation needs complementary dimensions of cooperation.

Concerning cooperation, Klapwijk and Van Lange (2009) consider that the majority of people are likely to engage in the same level of the cooperation they receive, tending to reciprocate positively or negatively, depending on the interactions. Mancenido (2011) considers that humans cooperate through strong reciprocity, once they naturally increase their cooperation with those who cooperate with them and, contrarily, tend to punish the ones that do not cooperate. Showing generosity – giving independently of what is expected to be received – is a key mechanism to overcome pure tit – for-tat interactions and to generate cooperation and trust (Klapwijk & Van Lange, 2009). These authors’ findings show that generous strategies that aim to benefit others can be more effective than adopting a stance of strict reciprocity. Acting prosocially towards others fosters greater collaboration, generates more positive interactions and feelings of happiness (Simpson & Willer, 2007). Bruni (2012) claims that equality, freedom and fraternity must be held together for civil society to flourish. Along similar lines, Bowles and Gintis (2011) believe that people have a genuine concern about the well-being of others, suggesting that this can also be a motive for cooperation. Prosocial individuals, who are driven by the willingness to help others, are often motivated by the purpose of satisfying others’ needs (Howard, Nelson, & Sleigh, 2011). This way, where Smith’s invisible hand fails, the handshake may succeed (Bowles & Gintis, 2011, p. 200). Collaboration is also a key piece for the well-funcioning of social systems. Working in articulation instead of segregated potentiates processes and outcomes (Marques & Ferraz, 2015).

Access to resources

In society, the worth of individuals tends to be assessed according to how much people have (Romero, 2003). Literature has been progressively recognizing the historically and structurally entrenched inequality dividing advantaged and disadvantaged groups, which compromise wellness for everyone in society (Deaton, 2003; Sen, 1982). There is a huge gap between those who are rich and those who are poor and that the deprivation of the poor is connected with the well-being of the rich. Such contrast does not promote connection, peace or common good; on the contrary, it sometimes prompts violence as well as indignation (Deaton, 2003; Piketty, 2014; Yunus, 2009). Effects of inequality and exclusion involve a larger burden for socio-economically disadvantaged communities that experience their opportunities for growth and social contribution as increasingly limited (Deaton, 2003).

Poverty, in a general sense, is the experience of lack of resources to meet needs. The statistical measure of the annual income needed for a family to survive is the most common and objective definition of poverty (Bradshaw, 2007; Costa, Baptista, Cardoso, & Rasgado, 1999). Definitions of poverty reflect political values and paradigms. Usually conservative theoretitians attribute the causes of poverty to individual factors, whilst liberals point to structural aspects. The complex causes that maintain the cycle of poverty need to be addressed complexly, and not by only focusing parts of the solution (Bradshaw, 2007). In the perspective of Costa et al. (1999) and Sen (1999), poverty is due to a lack of opportunity to choose and exercise agency. Participation in political decisions should be considered a constitutive part of development.

Research on poverty has been focusing on who loses in the economic context instead of on the context that produces the loosers in the first place (Tacket et al., 2009). To understand poverty, we need to look to the structure of economic classes and their interrelations. Comprehending poverty as an issue of stratification leads to understanding poverty as a question of inequality (Sen, 1982). Income and social position are also strongly associated with health. Wealthier people have longer and healthier lives (Deaton, 2003). Wilkinson (2004) suggests that health inequality is associated with stress, dominance and submission and, on other hand, equality generates balanced, supportive and more cohesive societies. Poverty is also known to be a strong trigger of social exclusion (Sen, 1982). Nonetheless social exclusion is broader than poverty, encompassing matters such as lack of rights and participation (Tacket et al., 2009).

Independently of the paradigm assumed, the world has become used to the idea that there will be always poor people. A collective motivation and effort is needed to overcome poverty (Yunus, 2009). A safety-net that guaranties support to everyone is a civic responsibility (Bradshaw, 2007).

Method

This study is part of a larger mixed methods research project, with a sequential design that involved two prior qualitative studies (Minas et al., 2018) as well as the quantitative study that is presented in this article. This study was informed by the qualitative findings of the previous studies which are synthesized below.

Qualitative insights: The dynamics of reciprocity theoretical framewok

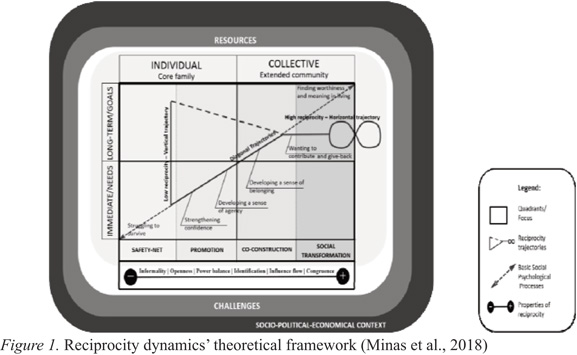

The reciprocity theoretical framework emerged from the study of 11 conversational sessions with participants from advantaged and disadvantaged backgrounds involved in 15 social programs internationally recognized as best practices in collaboration with disadvantaged individuals and communities (Minas et al., 2018). A grounded theory approach that included analyses of interviews, focus groups with participants and profesisonals and notes collected from participant observation led to the emergence of a theoretical framework centered in the dynamics of reciprocity and its centrality in the development of healthy and mutualy empowering relationships (see Figure 1).

The central line in the diagram depicts three trajectories of reciprocity: vertical, diagonal and horizontal. The vertical trajectory represents uneven top-down relationships and interactions that are oriented by lack of trust, power imbalance, control, distinction and formality between its participants. Such interactions are driven by an individualistic focus. The diagonal trajectory suggests more balanced and closer interactions, but still uneven and predominantly unidirectional. Finally, the horizontal trajectory is characterized predominantly by closeness and trust, informality, openness, mutual influence and balance of power. Relationships are driven by a collective focus, involving common benefits.

Four quadrants frame the focus and stances individuals assume depending on their social roles and economic positions. In the bottom-left quadrant, the focus is centered on the immediate moment and on individual needs; the upper-left quadrant points to individual goals on a long-term basis; the bottom-right quadrant is centered on immediate needs, at community and collective levels; and in the upper-right quadrant, goals and purposes projected in the future are at stake, involving collective dimensions. Along the line depicting trajectories of reciprocity, six basic social processes that contribute to developing individual and collective well-being are indicated, moving from struggling to survive to finding a sense of worthiness and meaning in living. A continuum of programs – safety-net; promotion; co-construction and social transformation – is presented at the bottom of the framework which correlates with the trajectories and processes emergent in this research. At the background of the framework, the first halo encompasses the resources and challenges that are present in the ecosystem and the second halo portrays the sociopolitical-economical context in which all the reciprocal processes are embedded.

Quantitative methodological design

Participants

The sample consisted of 1187 participants, 788 women (66,4%) and 399 men (33,6%), ages ranged from 18 to 70 (Mage=34,55; SD=11,25). Most participants had a higher education (81,4%). In respect to the professions, 476 participants had intellectual professions (40,3%), 256 participants had intermediate professions (21,6%), 150 were students (12,6%) and the other participants had either other professions (19,5%), were unemployed (3,9%) or retired (1,8%). Participants were mainly from the Lisbon area (63,2%) and the rest were spread among other Portuguese regions (33,6%) and abroad (3,6%). According to their own perceptions, 13 participants had a high economic level (1,1%), 217 had a medium-high economic level (18,3%), 678 participants had a medium economic level (57,1%), 238 participants had a medium-low economic level (20,1%) and 41 participants had a low economic level (3,5%). 624 participants were single (52,6%) and 466 were either married or living together (39,3%). Only 36,7% of the participants had children.

Measures

Satisfaction – The satisfaction with life was measured through the Portuguese version of the Satisfaction With Life Scale – SLS (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985, adapted by Simões, 1994). The purpose of this scale is to analyse the subjective well-being and the perception that individuals have about their own quality of life. The questionnaire is comprised by 5 items scored in a global factor. The higher the value, the higher the satisfaction with life. The original coefficient alpha was .87.

Competition – The competitive disposition was measured through the Portuguese version of the Striving to Avoid Inferiority Scale – SAIS (Gilbert et al., 2007, adapted by Ferreira, Pinto-Gouveia, & Duarte, 2011). The purpose of SAIS is to measure the motivations and fears that are associated to the need to compete to avoid a sense of inferiority. The original scale has three distinct parts and a total of 27 items.

Sense of community – The sense of community was measured through the Portuguese version of the Brief Sense of Community Scale – BSCS (Peterson, Speer, & MacMillan, 2008, adapted by Colaço & Lind, 2010 – see Colaço, 2010). The purpose of BSCS is to understand individuals’ sense of connection to a community. The Portuguese version has 8 items and is measured with a four level Likert scale. For the purpose of this research the introductory instruction was changed in order to give freedom to the participants to choose a community to which they belong (e.g., neighbourhood, cultural, faith or sports group, etc.). The original version demonstrated a precision of .92.

Perceived Social Support – The social provisions were measured through the Portuguese version of the Social Provision Scale – SPS (Cutrona & Russel, 1987, adapted by Moreira & Canaipa, 2007). The purpose of SPS is to analyse an individual’s perceived social support, according to a multidimensional lens. The Portuguese version of SPS has 24 items, distributed along six social dimensions (attachment, social integration, reassurance of worth, reliable alliance, guidance and opportunity for nurturance). Participants respond in a likert scale that varies from 1 to 4. The original scale presents a precision of .91.

Social Comparison – Social comparison was measured through the Portuguese version of the Social Comparison Scale – SCS (Allan & Gilbert, 1995, adapted by Gato, 2003). The purpose of SCS is to measure how individuals rate their relative social position, in a scale that ranges from 1 (inferior) to 10 (superior). The Portuguese version has 10 items. The precision of the original scale was .91.

External Shame – External shame was measured through the Portuguese version of the Other as a Shamer Scale – OASS (Goss, Gilbert, & Allan, 1994, adapted by Matos, Pinto Gouveia, & Duarte, 2012). OASS measures the extent to which others are seen as potentially depreciating one’s self, analysing how people think others are seeing them. The scale consists of 18 items and participants respond on a 5 points scale. In the original scale the precision was .92.

Willingness to Contribute – this scale (WCS) was developed in the context of this research to measure individuals’ willingness to contribute to the society. It has 10 items and the scale of response ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

Willingness to Contribute emerged in the qualitative study as a key-process in the development of relational and collective well-being. It was considered important to incorporate this scale in order to complement and enrich the protocol of variables in study.

Procedures

After defining the instruments which would integrate the study, 6 people participated in a test version, responding to the questionnaire in paper form and giving feedback respecting its clarity. With such contributes, some changes to the instructions were implemented. The final version of the questionnaire was then applied as an online form, through Qualtrics Survey Software. Data was collected from May 2014 until June 2015, through a convenience sampling process. As criteria for participation, each individual needed to be Portuguese and at to have at least 18 years old. The first page of the protocol described the purposes, ethics and confidentiality of the investigation, and participants who agreed to participate provided written consent. The scales were presented to all participants in the same order. Participants also responded to a socio-demographic form.

Results

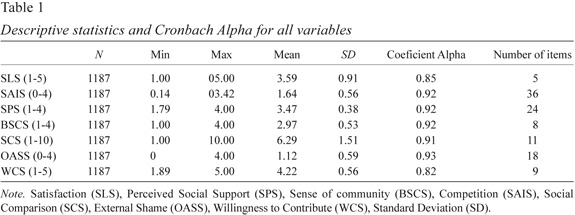

The statistical package IBM SPSS Statistics v.24 was used to perform all the statistical operations for this study. Due to the purposes of our study it was decided to use every scale as a global variable, not analysing each dimensional structure. The descriptive statistics and precisions of each scale were initially analysed (Table 1). All scales, after recoding the items that were presented in negative form and excluding item 4 for WCS, showed a strong precision. SLS, SPS, BSCS, SCS and WCS presented high values of response, OASS and SAIS presented low levels of response.

The normality of all the variables was analysed according to four criteria: Skew and Kurtosis coefficients, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Q-Q plots. It was concluded that the distribution of the data was not normal. That way, non-parametric tests were used to proceed with the analysis.

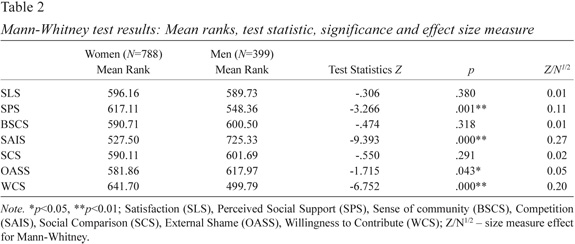

As a preliminary study, a statistical analysis using the Mann Whitney U test was performed to compare the distributions of the variables in study grouped by sex (Hipothesis 1). As shown in Table 2, only the variables Social Provisions (small size effect), Competition (intermediate size effect), External Shame (no size effect) and Willingness to Contribute (intermediate size effect) presented significant differences (p<0.001). Men score higher at Competition and External Shame and lower at Perceived Social Support and Willingness to Contribute than women.

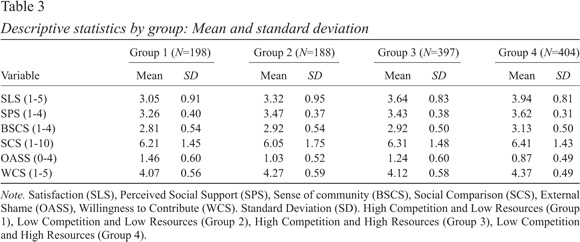

To take the analysis further, a definition of groups based on a previous qualitative study by Minas et al. (2018), in which a crossing of Competition and Resources was carried out, in order to obtain 4 groups. The variable Resources was created transfoming the 5 levels of the Perceived Economic Level variable into two levels, following the sequent process: high and medium-high levels were recoded into high level of Resources, low and medium-low levels were defined as low level of Resources; finally, the medium levels were divided into high or low Resources, considering the profession and educational levels. Competition was also recoded into two levels, weather the means of the responses were above or below average. The 4 groups obtained were G1 – High Competition and Low Resources, G2 – Low Competition and Low Resources, G3 – High Competition and High Resources and G4 – Low Competition and High Resources.

Group 1 – High Competition and Low Resources – is composed by 198 participants (16,7%) who believe they need to compete to avoid being seen as inferior and who have a low economic background. They present the lowest values for SLS, SPS, BSCS and WCS. Respecting SCS, its values appear as the second lowest. Contrastingly, OASS concentrates the highest values (Table 3). Group 2 – Low Competition and Low Resources – is composed by 188 participants (15,8%) who believe they do not need to compete to succeed in life and who have a low economic background. They present the lowest values for SCS while SLS and OASS present the second lowest values. SPS, BSCS and WCS variables appear as the second highest (Table 3). Group 3 – High Competition and High Resources – is composed by 397 participants (33,4%) who believe they need to compete to avoid being seen as inferior and have a high economic background. They present the second lowest values for SPS, BSCS and WCS. SLS, SCS and OASS variables appear as the second highest (Table 3). Group 4 – Low Competition and High Resources – is composed by 404 participants (34%) who believe they do not need to compete to succeed in life and who have a high economic background. They present the highest values for SLS, SPS, BSCS, SCS and WCS. These participants score the lowest values for OASS (Table 3).

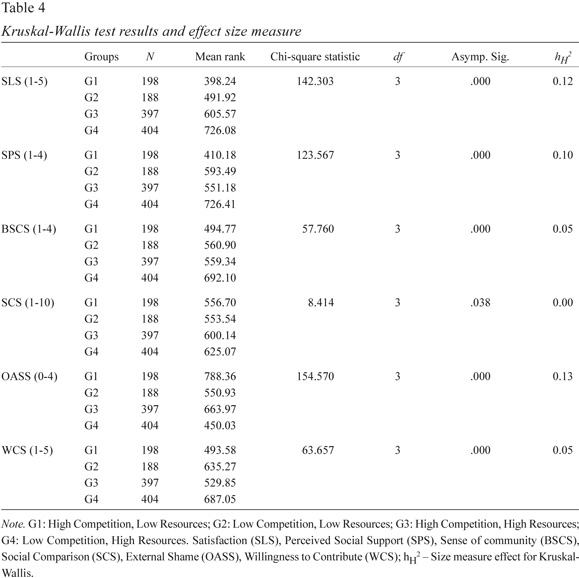

The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to study the behaviour of SLS, SPS, BSCS, SCS, OASS and WCS through the four groups (Table 4) and it was verified that the six variables distributions are significantly different between groups (p≤0.05). Considering the significant results obtained with the Kruskal-Wallis test, pairwise comparisons were analysed to understand which pairs of groups present significant differences (see Attachment 1). SLS distribution is statistical different between all pairs of groups (p<0.05); for SPS distribution most groups present significant statistical differences between each other, except between G2 and G3 (p>0.05); for BSCS variable the significant differences between group G4 and the others three groups (G1, G2 and G3) are evident (p<0.00), nonetheless G1, G2 and G3 do not present significant differences between them (p>0.05); the SCS distribution shows no significant differences between all groups (p<0.05); the variable OASS distribution presents significant differences in all pairs of groups (p<0.01); finally, in the WCS distribution, groups G1 and G3 did not present significant differences between themselves (p>0.05) as well as groups G2 and G4 (p>0.05). Respecting the effect size measure obtained in each case (Table 4), it’s possible to know the magnitude of the differences reported. It was noted that the variables SLS, SPS and OASS present an intermediate effect size; BSCS and WCS present a small effect size and SCS presents no effect size.

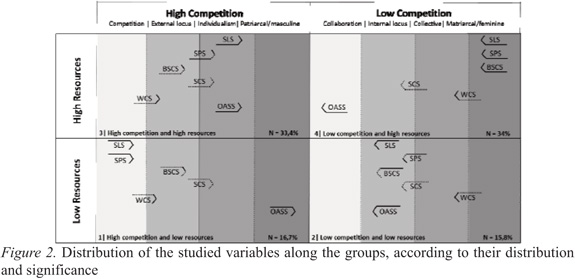

Based on these findings, a chart was created (Figure 2) to represent the distribution of the studied variables along the groups, according to the magnitude of their mean and significance between groups.

Figure 2 reflects the behaviour of the variables within each group and allows the comparison between them. Using a color gradient, variables were classified by their order of magnitude, from the lowest to the highest, considering four levels corresponding to the number of groups (see Table 3). Also, each variable is surrounded by a line with three sides that point to the same variable in the other three groups. Each side can be bold or dotted depending on the existence, or not, of statistical differences of the same variable distribution between two groups.

When a variable presents a statistical difference between all groups (SLS and OASS), it is represented surrounded by a bold line and is positioned in each group according to its order of magnitude: the lowest which is in the first rectangle to the highest which is in the fourth rectangle. The SPS variable presents significant differences between G1 and G4 with the lowest and highest order of magnitude, respectively. Contrastingly, G2 and G3 do not differ significantly, therefore the variable is positioned, in both groups, in the middle of the second and third orders. BSCS variable only presents significant differences between G4 when compared with G1, G2 and G3. Since it has the highest order of magnitude for G4 it is positioned in the fourth rectangle of this group, while in the other groups it is positioned in the centre of the three first rectangles. In the case of SCS variable, that does not present statistical differences between all groups, it is positioned in the centre of each group, being surrounded by a dotted line since there is no order of magnitude. Finally, WCS only presents significant differences between High Competition (G1; G3) and Low Competition (G2; G4). The High Competition groups have the lowest orders of magnitude, being positioned between the first and second rectangle. Contrastingly, the highest order of magnitude belongs to the Low Competition groups, being positioned between the third and fourth rectangle.

Discussion

The combination of Low Competition (collaborative and trusting stance) and High Resources (Group 4) appears to involve the highest levels of SLS, SPS, BSCS and the lowest levels of OASS. The variable SCS does not present any statistical differences between groups and WCS does not present statistical differences between G4 and G2. Nonetheless, the significant differences that were found in WCS suggest that the values in this group are amongst the highest. In contrast, the lowest levels of SLS, SPS, BSCS and the highest levels of OASS seem to be connected with High Competition and Low Resources (Group 1). The variables BSCS, SCS and WCS didn’t present statistical differences between G1 and all the other groups. However, the significant differences that were found suggest that the values in this group are amongst the lowest. The combination of Low Competition and Low Resources (Group 2) is associated with the second lowest levels of SLS and OASS. There were no significant differences between variables SPS, BSCS, SCS and WCS in G2 and in the other three groups. Nevertheless, the statistical differences that were found point to this group as concentrating one of the highest values for WCS and medium values in SPS and BSCS. Finally, the combination of High Competition and High Resources (Group 3) concentrates the second highest levels of SLS and OASS. There were not found significant differences between variables SPS, BSCS, SCS, and WCS in G3 and all the other three groups. Nevertheless, the statistical differences that were found point to this group as concentrating one of the highest values for WCS, while showing medium values in SPS and BSCS. Findings suggest that High Competition groups (G1 and G3) have greater levels of OASS and lower levels of WCS than the Low Competition groups (G2 and G4). The High Resources groups (G3 and G4) have greater SLS than the Low Resources groups (G1 and G2). It seems that the competition variable has greater impact in the values of OASS and WCS than the resources. In other hand, the level of resources seem to have greater impact on SLS than the level of competition. Nevertheless, in presence of similar resources, the level of SLS is higher when the competitive strive is lower (greater trust and collaboration). It is also relevant to note that SLS, SPS and OASS have an intermediate size effect, which means that the differences that were found between groups are mostly due to the size of differences than from the size of the sample. BSCS and WCS present a small size effect, which gives confidence, although small, that the differences are due to their magnitude, instead of by the size of the sample. SCS presents no size effect, which is in line with the lack of significant differences. The SPS is the highest in the group with Low Competition and High Resources and is the lowest in the High Competition and Low Resources group. Nonetheless, it seems to be equal in the presence of both low-low or high-high competition and resources. Respecting SCS, the differences between groups are not significative and present no size effect, which suggests that, in this sample, the flutuations in the level of resources and competition do not affect how individuals compare themselves to others. BSCS is emphasized with the highest values in the group of High Resources and Low Competition, being equal in the other groups. The findings suggest that the dimensions of collaborating (trusting) or competitive strive (perceiving others as a threat) seem to be what most counts. More than the resources (to have), individuals seem to be more affected by the quality of their relationships (to be). Access to resources also seems to be important, contributing to improved satisfaction with life, which is escalated when combined with a collaborative strive.

These findings are generally supportive of the Dynamics of Reciprocity Theoretical Framework (Minas et al., 2018) which indicates that relationships that are based on trust and a sense of colaboration, involving the interchange and access to resources, sustain individual and collective well-being in a more consistent way.

This is consistent with research in this field that has shown that members who cultivate a cooperative stance have an advantage in relation to members of non-cooperative groups (Bowles & Gintis, 2011). Developing healthy relationships and sense of belonging to a social group is key for individuals to be able to live well and grow (Gilbert & Procter, 2006). According to Bruni (2012), reciprocity and collaboration are fundamental principles of civil life.

Our findings also suggest that even though competitive and vertical relations may generate satisfaction for individuals who hold more powerful and resourceful positions than others, they do not contribute to the development of mutually empowering situations, constraining the development of trust, sense of community, perceived support and willingness to contribute. These findings seem to challenge Sayago’s (2008) observations respecting the overvalorization of the dimension of having and the undervalorization of the dimension of being. These results also seem to corroborate the social ranking’s theory (Gilbert, 1989, 1992; Price & Sloman, 1987), which states that a competitive disposition is adopted as an adaptive response towards social threats, when individuals experience the need to compete for resources or status. As a consequence, they become more self-centered, looking to defend themselves from humiliation and shame, and lose their sensitivity to others, becoming less available to help. Consistently with the findings, concerning the group with low resources and high competition, individuals who find themselves in low status situations tend to feel inferior and to develop a submissive behavior, involving social anxiety and depression (Gilbert, 2000).

According with the results shown in the High Competition groups, Gurtman (1992) also found that symmetrical dominant-passive interactions are related with distrust, whilst high trust is associated with more reciprocal and collaborative relationships. Piketty (2014) discusses the unequal effects of pure competition, arguing that those who have more will keep defending their interests and the ones who have less will be kept at a disadvantage. Instead, Piketty (2014) suggests the combination of competition with a logic of cooperation, which could involve progressive annual taxes on capital, to counteract the cicle of inequality. Studies on the sense of community have also explored the factors that promote cohesion and the care for each other. Consistent with our findings, which suggest that the sense of community is higher in the presence of Low Competition and High Resources, McMillan and Chavis (1986) observed that to develop a strong sense of community the group needs to have the capability of meeting both the needs of the group and of each individual. On the other hand, Amaro (2007) maintains that the community is a group of people that have a common sense of belonging and that interacts and shares resources, interests, and the like.

Our study points to the fact that not only a collaborative stance, but also the access to resources contribute to individual and collective well-being. The results associated with Low Competition and High Resources suggest the importance of developing collaborative approaches (involving the interchange of support, resources and competences) to develop human capital. In respect to the resources factor, the findings support the literature in the field, indicating that both having access to resources and interchanging resources is key for attaining relational and collective well-being. Wilkinson (2004) stresses that deprivation imposes multiple costs on society. Since a considerable part of the population lives in poverty, people become a burden rather than contributors to the society’s welfare. Romero (2003) emphazises the importance of participation in the construction of the common good. By focusing on the common good, ideas of integration and caring for each other prevale. Our findings suggest that when individuals have access to resources and do not have a competitive disposition (collaborating, trusting and sharing, instead), satisfaction with life, perceived social support, sense of community and willingness to contribute are at their highest level, in contrast with external shame, which is at its lowest level.

Respecting the descriptive statistics of each variable, the values suggest that the participants of this research are mostly satisfied with life and with their social relationships. Nonetheless, it can also point to the possibility of social desirability motivations. In respect to the high levels of WCS, it should also be considered that volunteering and providing support is becoming popular in Portugal. Acknowledging that the sample is not representative, it is important to consider if the results reveal connections with Portuguese cultural aspects. As Gutierrez (1975) expresses, a critical reflection about the economic and sociocultural aspects of life is fundamental. The Portuguese culture is entrenched in emotionality and human affection, thanks to their history and miths. The heart is the measure of all things (Mateus et al., 2013, p. 34; Mendes, 1996). The importance of the relational dynamics for the Portuguese people, which is connected with the sense of community, social support, willingness to contribute and trust – is aligned with the findings. The Portuguese culture is on the one hand deeply individualistic, but it has also a strong sense of solidarity. Sebastianism has left an inheritance of hope that things may happen miraculously. The Portuguese have also a strong trait of adaptability, which helps them strive in different environments and surroundings (Mateus et al., 2013). The high level of satisfaction, independently of the level of resources and perceived sense of support, seems to be in line with these traits.

Concerning the comparison of the mean ranks of the scales by sex, findings show that men score is higher at competition and lower at perceived social support and willingness to contribute. Such differences seem to suggest that men are more driven by competitive values, whilst women tend to be guided by collaborative values. Respecting satisfaction, the distributions do not present statistical differences between women and men. In the case of external shame, even though the value of p indicates there are significant differences between sexes, the magnitude of the differences is very low. Individuals’ behaviors and perceptions are connected with their cultural context and influenced by gender roles – the behavior that is expected for women and men (Chrisler, 2004).

These results add some insights to the Dynamics of Reciprocity Theoretical Framework (Figure 1): the left side is most centered in vertical dynamics, including competition and an individual perspective – which, in this study, appears to be more connected to the standpoints of men; the right side is characterized by horizontal trajectories, involving collaboration and a more collectivist perspective – which in this study appears as more connected with the standpoints of women. Such findings also seem to be aligned with the literature respecting patriarcal and feminist perspectives and values (Kruger, Fisher, & Wright, 2014; Sultana, 2011). Patriarchy is associated with male competition for the detainment of resources, power and to hold positions of high status (Kruger et al., 2014). Jonhson (1997) suggests patriarchy encouradges men to seek security, to fear others and to consider being in control as the best defense and the best way to achieve needs and desires. Men are expected to be masculine (in the traditional sense), independent, strong, powerful, invulnerable, and non-emotional (Becker, 1999). In relationships between couples, usually the men detain more power than the women (Felmlee, 1994). In contrast, the feminist ideology aims to deconstruct the hierarquical relationship and asymmetry between men and women (Sultana, 2011). The feminine gender has been traditionally associated with care, vulnerability, support, emotions, empathy and the importance of relationships, which has been undervalued (Becker, 1999). Our findings also suggest that if the values that are usually associated with the feminine gender such as collaboration, support, willingness to contribute are more integrated into societal practices and institutions, then the potential and trust of individual and collective systems would be greater.

Conclusion

These research results suggest that both resources and the level of competition (competitive or collaborative stances) influence the level of satisfaction with life, perceived social support, sense of community, willingness to contribute and external shame. They also seem to clearly point to the combination of Low Competition and High Resouces as the one capable of generating greatest welfare. The majority of the participants of this study seem to be satisfied with life and the quality of their relationships, tending to trust others, showing low need to compete and external shame. More specifically, women present greater willingness to contribute and perceived social support and men presented higher levels of competition.

These findings seem to corroborate the qualitative findings that emerged in our prior research, confirming the pertinence of cultivating relations that are oriented by collaborative and reciprocal values. Bringing to the fore the importance of collective dimensions, this study points to the interweaving of a person’s attitudes and relational stances, in the pursuit of individual, relational and collective well-being.

With respect to the implications, this research emphazises the importance of fostering the dimensions of being and of collaborating, exploring their potential to promote the well-being of individuals, communities and organizations. It also opens space for investigations and practices that integrate the diverse systems and do not focus only on the individuals that appear to show signs of lack of well-being or health.

As for some limitations of this study, it was based on a convenience sample, therefore the findings may not be truly representative and cannot be generalized to the Portuguese population. The implementation of a snowball sampling strategy and the use of an online questionnaire may also constrain the distribution of the sample, limiting the participation of low-income and older participants. Finally, since the responses of the participants were not generally at the extremes of the scales (having very few participants using the highest or lowest values of the scales to respond), the definitions of the levels of the groups – high and low – are only slightly differentiated, which may have impacted the number of statiscal differences which were found between groups.

As suggestions for further research it would be useful to make a similar study with a representative sample. Also, other statistical analyses such as correlational analysis, hierarchical regressions, and structural equation modeling could be performed to extract additional significant information from the collected data. It would be interesting to analyse, with a sample with more diverse sociodemographics, the behaviour of the variables and to re-compare the statistical differences between groups. It could also be relevant to continue developing the Willingess to Contribute Scale and to add items to access if the willingness is congruent with the practices of contribution. Another way of continuing exploring this work would be to study the sense of social connection across status, cultures and nations. Considering the generated groups, it would be very interesting to analyse the behavior of variables such as self-confidence and trust. Finally, the creation of a scale to assess the dynamics of reciprocity that could be applied to relationships and programs, would be of added value for countries to be able to assess the quality of the relationships, at different levels and systems.

References

Allan, S., & Gilbert, P. (1995). A social comparison scale: Psychometric properties and relationship to psychopathology. Personality and Individual Differences, 19, 293-299. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(95)00086-L [ Links ]

Amaro, J. (2007). Sentimento psicológico de comunidade: Uma revisão. Análise Psicológica, 25, 25-33. [ Links ]

Becker, M. (1999). Patriarchy and inequality: Towards a substantive feminism. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Legal Forum. Retrived from http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1999/iss1/3 [ Links ]

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (2011). A cooperative species: Human reciprocity and its evolution. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Bradshaw, T. K. (2007). Theories of poverty and anti-poverty programs in community development. Journal of Community Development, 38, 7-25. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330709490182 [ Links ]

Bruni, L. (2012). The wound and the blessing: Economics, relationships, and happiness. New York: New City Press. [ Links ]

Colaço, M. (2010). Comunidades reconstruídas: Sentido de comunidade e apoio social percebido no pós-realojamento. Dissertação de Mestrado, Faculdade de Psicologia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal. [ Links ]

Costa, A. B., Baptista, I., Cardoso, A., & Rasgado, S. (1999). Pobreza e exclusão social em Portugal. Prospectiva e Planeamento, 5, 49-120. [ Links ]

Chrisler, J. C. (2004). Gender role development. In C. Spielberger (Ed.), Encyclopedia of applied psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 85-90). Oxford: Elsevier Academic Press. [ Links ]

Cutrona, C. E., & Russell, D. (1987). The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. In W. H. Jones & D. Perlman (Eds.), Advances in personal relationships (Vol. 1, pp. 37-67). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. [ Links ]

Deaton, A. (2003). Health, inequality, and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature, 41, 113-158. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3386/w8318 [ Links ]

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. [ Links ]

Doron, R., & Parot, F. (2001). Dicionário de psicologia. Lisboa: Climepsi Editores. [ Links ]

European Comission. (2009). Economic crisis in Europe: Causes, consequences and responses. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/pages/publication15887_en.pdf [ Links ]

Felmlee, D. H. (1994). Who’s on top? Power in romantic relationships. Sex Roles, 31, 275-295.

Ferreira, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, C. (2011). The validation of the body image acceptance and action questionnaire: Exploring the moderator effect of acceptance on disordered eating. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 11, 327-345. [ Links ]

Gato, J. J. (2003). Evolução e ansiedade social [Evolution and social anxiety]. Tese de Mestrado, Faculdade de Psicologia e Ciências de Educação, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal. [ Links ]

Gilbert, P. (1989). Human nature and suffering. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hove. [ Links ]

Gilbert, P. (1992). Depression: The evolution of powerlessness. Guilford: NewYork. [ Links ]

Gilbert, P. (1997). The evolution of social attractiveness and its role in shame, humiliation, guilt and therapy. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70, 113-147. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1997.tb01893.x [ Links ]

Gilbert, P. (2000). The relationship of shame, social anxiety and depression: The role of the evaluation of social rank. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 7, 174-189. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0879(200007)7:3<174::AID-CPP236>3.0.CO;2-U [ Links ]

Gilbert, P., Broomhead, C., Irons, C., McEwan, K., Bellew, R., Mills, A., . . . Knibb, R. (2007). Development of a striving to avoid inferiority scale. British Journal of Social Psychology, 46, 633-648. Retrieved https://doi.org/10.1348/014466606X157789 [ Links ]

Gilbert, P., & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 13, 353-379. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.507 [ Links ]

Goss, K., Gilbert, P., & Allan, S. (1994). An exploration of shame measures. I: The other as shamer scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 17, 713-717. [ Links ]

Gurtman, M. B. (1992). Trust, distrust and interpersonal problems: A circumplex analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 989-1002. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.62.6.989 [ Links ]

Gutierrez, G. (1975). Teologia de la liberacion (2nd ed.). Salamanca: Ediciones Sígueme. [ Links ]

Howard, A., Nelson, D., & Sleigh, M. (2011). Predictors of beliefs about altruism and willingness to behave altruistically. Psi Chi Journal of Undergraduate Research, 16, 168-174. [ Links ]

Jonhson, A. G. (1997). The gender knot: Unraveling our patriarcal legacy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [ Links ]

Klapwijk, A., & Van Lange, P. A. (2009). Promoting cooperation and trust in “noisy” situations: The power of generosity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 83-103. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0012823

Kruger, D. J., Fisher, M. L., & Wright, P. (2014). Patriarchy, male competition and excess male mortality. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 8, 3-11. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0097244 [ Links ]

Mancenido, Z. (2011). Why cooperate? The place of stong reciprocity in the evolution of human altruism. The ANU Undergraduate Research Journal, 3, 29-45. [ Links ]

Maner, J., & Gailliot, M. (2007). Altruism and egoism: Prosocial motivations for helping dependente on relationship contexto. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 347-358. [ Links ]

Marques, R., & Ferraz, D. (2015). Governação integrada e administração pública. Lisboa: INA Editora. [ Links ]

Mateus, A., Silva, C., Mateus, J., Romão, J., Ferreira, N., & Gouveia, S. (2013). A cultura e a criatividade na internacionalização da economia portuguesa. Gabinete de Estratégia, Planeamento e Avaliação Culturais. Retrieved from http://www.portugal.gov.pt/media/1325076/20140131%20sec%20estudo%20cultura%20internacionalizacao%20economia.pdf [ Links ]

Matos, M., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, C. (2012). Other as shamer: Versão portuguesa e propriedades psicométricas de uma medida de vergonha externa. Manuscript submitted to publication. [ Links ]

McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 6-23. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<6::AID-JCOP2290140103>3.0.CO;2-I [ Links ]

Mendes, J. M. (1996). Características da cultura portuguesa: Alguns aspectos e sua interpretação. Revista Portuguesa de História, 1, 47-65. [ Links ]

Minas, M., Ribeiro, M. T., & Anglin, J. P. (2018). Trajectories on the path to reciprocity: A theoretical framework for collaborating with socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. American Journal of Ortho-psychiatry, 88, 112-123. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ort0000239 [ Links ]

Moreira, J., & Canaipa, R. (2007). Escala de provisões sociais: Desenvolvimento e validação da versão portuguesa da Social Provision Scale. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico e Avaliação Psicológica, 2, 24. [ Links ]

OECD Better Life Index. (2012). Retrieved from http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/pt/paises/portugal-pt/ [ Links ]

Peterson, N. A., Speer, P. W., & McMillan, D. W. (2008). Validation of a brief sense of community scale: Confirmation of the principal theory of sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 61-73. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20217 [ Links ]

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambrige: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Price, J. S., & Sloman, L. (1987). Depression as yielding behaviour: An animal model based on Schjelderup-Ebb’specking order. Ethology and Sociobiology, 8, 85-98.

Romero, O. (2003). The violence of love. Farmington: The Bruderhof Foundation. [ Links ]

Sayago, R. (2008). Participação: Olhar para fora ou olhar para dentro?. Ra Ximhai, 3, 543-558. [ Links ]

Sen, A. (1982). Poverty and famines. Oxford: Claredon Press. [ Links ]

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. New York: Anchor Books. [ Links ]

Simões, M. M. (1994). Investigação no âmbito da aferição nacional dos Testes das Matrizes Coloridas de Raven. Dissertação de Doutoramento, Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências de Educação, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal. [ Links ]

Simpson, B., & Willer, R. (2007). Altruism and indirect reciprocity: The interaction of person and situation in prosocial behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71, 37-52. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250807100106 [ Links ]

Smith, A. (1759). The theory of moral sentiments. London: A. Millar and A. Kincaid and J. Bell. [ Links ]

Sultana, A. (2011). Patriarchy and women’s subordination: A theoretical analysis. The Arts Faculty Journal, 4, 1-18. Retrieved https://doi.org/10.3329/afj.v4i0.12929

Tacket, A., Crisp, B. R., Nevill, A., Lamaro, G., Graham, M., & Barter-Godfrey, S. (Eds.). (2009). Theorizing social exclusion. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Van Lange, P. A. (2000). Beyond self-interest: A set of propositions relevant to interpersonal orientations. European Review of Social Psychology, 11, 297-331. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/14792772043000068 [ Links ]

Waldegrave, C. (2009). Cultural, gender, and socioeconomic contexts in therapeutic and social policy work. Family Process, 48, 85-101. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01269.x [ Links ]

Wilkinson, R. (2004). Why is violence more common where inequality is greater?. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1036, 1-12. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1330.001 [ Links ]

Yunus, M. (2009). Creating a world without poverty: Social business and the future of capitalism. New York: Public Affairs. [ Links ]

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Maria Minas, Faculdade Psicologia, Universidade de Lisboa, Alameda da Universidade, 1649-013 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: maria.minas@gmail.com

This study was supported by one grant by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (SFRH/BD/70322/2010).

Submitted: 29/12/2018 Accepted: 13/06/2019