Análise Psicológica

ISSN 0870-8231 ISSN 1646-6020

https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1460

Humiliation Inventory: Adaptation study for Portuguese population

Inventário de Humilhação: Estudo de adaptação para a população Portuguesa

Francisco M. S. Cardoso1, Ana C. M. Ramos1, Linda M. Hartling2

1Laboratório de Psicologia Experimental Clínica, UTAD – Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Vila Real, Portugal

2Director of Human Dignity and Humiliation Studies, Lake Oswego, Oregon, USA

ABSTRACT

The objective is to present the adaptation study of the Humiliation Inventory for the Portuguese population. The starting point was Hartling and Luchetta’s version, composed of thirty-two items, distributed by two factors – cumulative humiliation and fear of humiliation. 1116 participants of the general population, Mage=32.25, DPage=11.5, took part in the study. The confirmatory factor analysis did not register satisfactory indexes for a two-factor composition. Consequently, we searched for the alternative models. First, with the principal component analysis, three factors were extracted, corresponding to cumulative humiliation, fear of humiliation and a third factor corresponding to concern/ worry about being a victim of humiliation. They explain approximately 72% of total variance and present good reliability. Subsequently, with the CFA we observed that the three-factor model, following respecification, had a very good fit, Satorra-Bentler(factor correction)=1.416, χ2(196)=570.766, χ2/df=2.91, CFI=.984, TLI=.981, RMSEA=.041, CI [.038, .045], SRMR=.028, as well as composite reliability and factorial, convergent and discriminating validities. In conclusion, this version puts forward an additional measure of concern/worry regarding humiliation, which, in the original version, was aggregated into the measure of fear of humiliation. We believe the distinction is due to sample and cultural characteristics.

Key words: Humiliation, Non-dignity, Interpersonal conflict, Violence.

RESUMO

Temos como principal objetivo apresentar um estudo de adaptação de um inventário de humilhação para a população Portuguesa. Tivemos como ponto de partida a versão original do inventário de Hartling e Luchetta (1999) composto por trinta e dois itens distribuídos por dois fatores: humilhação cumulativa e medo da humilhação. Participaram 1116 respondentes da população geral, Midade= 32.25, DPidade=11.5. Procedemos a uma AFC que não confirmou a estrutura fatorial inicial. Por consequência, procurámos modelos alternativos. Em primeiro lugar, realizámos uma ACP da qual resultou a extração de três fatores, denominados por humilhação cumulativa, medo/receio de humilhação e preocupação para com a humilhação que explicam cerca de 72% da variância total e apresentam boa fiabilidade. Subsequentemente, realizámos uma AFC que, após reespecificação, confirmou o modelo de três fatores com muito bom ajustamento: Satorra-Bentler(factor correction)=1.416, χ2(196)=570.766, χ2/df=2.91, CFI=.984, TLI=.981, RMSEA=.041, CI [.038, .045], SRMR=.028. De modo semelhante, apresentou bons valores respeitantes à fiabilidade compósita e fatorial e boas validades convergente e discriminante. Em conclusão, o estudo de adaptação conferiu um bom instrumento de medida, realçando um novo fator - preocupação para com a humilhação - o qual, na versão original, estava agregado ao segundo fator, medo/receio de humilhação. Esta diferença encontrada dever-se-á à diferente composição da amostra e a diferenças culturais específicas.

Palavras-chave: Humilhação, Dignidade, Conflitos interpessoais, Violência.

Experiences of humiliation penetrate the core of our identity that defines who we are and what we need to be, be it in one’s self-definition as an individual or assumptions about one’s social roles and status, through emotional experiences lived in interaction (Stets & Trettevick, 2014). An identity process that has a long path of development is well supported by developmental psychology, with a particular emphasis on motivation and affectivity theories that show that “to be” is being in personal expression, in authentic engagement (Fineman, 2004; Jordan, Walker, & Hartling, 2004; Miranda-Santos, 1972) with a sense of belonging (Deci & Ryan, 2012; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). In this sense, humiliation also becomes the antithesis of caring value presented by Heidegger in Being and Time (1927/2010), which we consider to be foundational of human dignity.

Concerned about the lack of research on the experience and consequences of humiliation, Hartling (1996; see also Hartling & Luchetta 1999) developed the first instrument to assess the impact of this experience, the Humiliation Inventory (HI). Since then, the HI has been translated into Italian, French, Japanese, Korean, Russian, and Norwegian (the respective adaptations studies are in progress), extending the study of humiliation around the world. We acknowledge and hope that this scale will continue as a useful instrument for the study of this phenomenon across cultures and continents, but it has not been translated into Portuguese yet.

Recognizing that the predominant psychology theories focus on internal dynamics arising from Western psychology’s “intrapsychic” model (Cushman, 1995), the authors of this study emphasize that the experience of humiliation should be analysed and considered within the context of a broader cultural and relational perspective (Jordan & Hartling, 2002). In particular, we are concerned about humiliation and the psychosocial dynamics associated with interpersonal aggression and violence, be it domestic, while dating, sexual, mobbing, or bullying (Hollin, 2016; Lindner, 2010; Negrão, Bonanno, Noll, Putnam, & Trickett, 2005). When examining the psychosocial dynamics associated with interpersonal violence, for example, one finds humiliation is a common characteristic, which materialises in the devaluation, denigration, and negation of the other (Hartling & Lindner, 2016; Leask, 2013). On a profound level, humiliation can inhibit, obstruct, and even annihilate one’s personal expression of being a person in the Rogerian expression. We suggest that humiliation is pervasively present in these types of events; nevertheless, it is treated as a cameo subject of interest, not as the main character, and is disregarded by legislators.

The global, transdisciplinary community of scholars has been striving to reverse the underestimation and misrecognition of the impact of humiliation by studying micro and macro-social consequences of this experience, especially as it relates to the conflict between humans and across different cultures (Lindner, 2013). The effort to draw attention to such a serious issue has been great, as underlined by Hartling and Lindner (2017, p. 50): “we cannot wait for our political leaders to address global social crises of humiliation. Everyone is called onto help dismantle this dynamic starting today”. Additionally, the United Nations must produce specific actions and to provide reports that shed light on the human drama of the humiliation practice and its consequences such as violence, interpersonal and ethnic conflicts that dwells in our daily life. A mission that is being taken by the Human Dignity and Humiliation Studies Organization led by Linda Hartling and Evelin Lindner (humiliationstudies.org).

This is the time to question: Why has it taken so long for concerns about the impact of humiliation to come to the attention of scholars and researchers?

One explanation of why humiliation has been neglected may be it’s insidious and stealthy impact on its victims. Contrary to the visible physical aspects of interpersonal violence, humiliation, as its etymology indicates, being derived from the Latin humiliare, relates to inflicted “wounds” that are not observable. Perhaps the fact that the wounds of humiliation are not obvious explains why its conceptualisation has only recently received due attention. The less invisible nature of humiliation requires that we listen closely to the voices of the victims reflecting on their perceptions of being degraded or dehumanized by interpersonal mistreatment. Whether or not humiliating mistreatment had been carried out through the interpersonal triptych referred to by Klein (1991) involving a humiliator, bystanders, and a victim, or it occurs within more complex interpersonal conditions or occurs between groups (Leidner, Sheikh, & Ginges, 2012), the invisible nature of the wounds may have delayed progress toward fully conceptualizing this experience.

The second reason for such a late conceptualisation of the notion of humiliation lies in the understanding that humiliation is often confused and conflated with the emotion of shame. There are, however, significant differences between these two experiences (Fernández, Saguy, & Halperin, 2015); therefore, it is advantageous to distinguish the affective complexity resulting from humiliation, limiting the semantic field to not only that of shame, but also the other emotions that trigger self-consciousness, among which are embarrassment and guilt. In fact, although it may be said that these emotions are socially constructed, according to social dynamics, emotions that trigger self-consciousness are still seen as being developmentally integrated into the subjects’ psychological organisation (Lewis, 2016a; Ryan, 2017; van Alphen, 2017; Vanderheiden & Mayer, 2017), according to different aspects or themes of life (Lazarus, 1991), whether serving one’s self or serving social regulation (Frevert, 2016; Gilbert, 2003). As stated by Gilbert (2010), shame lies between our judgment of ourselves and the judgment of others according to socially accepted standards; this transmutes into embarrassment if the emotion felt is of lesser intensity, thus resembling shyness (Lewis, 2016b). Guilt calls for a reflection on responsibility and a reassessment of a given action (Cohen, 2017); it may, as a consequence of such reassessment, provoke regret in the agent and compassion for those who suffered with the agent’s action. In fact, it is this hetero and self-regulatory dynamism that gives emotions an important developmental and societal utility (Cardoso, 2015). On the other hand, the experience of humiliation, from humiliating-acts to the damages – embodied – produced and observed through an analysis of the psychological experience of the humiliated-victim, surpass the definitional boundaries of shame (self/other judgment), embarrassment (less intense self/other judgment), and guilt (a sense of responsibility for a specific harmful act).

Humiliation results from interpersonal, social, or systemic interactions that undermine, devalue, or destroy an individual’s psychological well-being and fundamental sense of dignity (worth), disrupting one’s affective-emotional organisation (Hartling & Lindner, 2016; Leidner et al., 2012). A good example of this is found in the following sentence: “The offender seeks to vent his anger through injuring the victim by the use of excessive physical force: the rape may be a means of inflicting pain and humiliation rather than a sexual act per se” (Hollin, 2016, p. 138). Indeed, in the victim, the traumatically humiliating act of rape generates a tidal wave of emotional phenomena such as anger, and the feeling of injustice, shame, or vengefulness; a fact that led Hartling, Lindner, Spalthoff and Britton (2013) to consider humiliation as a nuclear bomb of emotions. In this sense, the lack of research conceptualising humiliation as a profoundly damaging social and interpersonal phenomenon, may be equivalent to a concealment of dehumanizing practices that, in the subject who is suffering, may produce devastating consequences, such as severe depression and suicide at one end of the scale (Collazzoni et al., 2015; Kendler, Hetetma, Butera, Gardner, & Prescot, 2003; Torres & Bergner, 2010) and violent behaviour on other (Hartling, 2007; Jogdand & Sinha, 2015; Silfver-Kuhalampi, Figueiredo, Sortheix, & Fontaine, 2015).

In short, humiliation is an interpersonal or social act with cascading psychological ramifications. The act of humiliating, often an action of someone who is exerting his dominion over others, may be analyzed from multiple levels, including psychosocial, political, and clinical levels. It seems, therefore, important to provide an assessment instrument aimed at identifying humiliation experiences within a cultural context, that will lead to effective clinical, educational, and political practices designed to effectively address the damaging consequences of this experience. This is what we intend to accomplish with this article testing and analysing a Portuguese translation of the Humiliation Inventory (Hartling, 1996). In summary, the structure of the original HI consists of a two-factor model: the cumulative humiliation factor, with 12 observed variables, and the fear of humiliation factor, with 20 observed variables. These factors correlate with each other by a value of .55.

Method

Participants

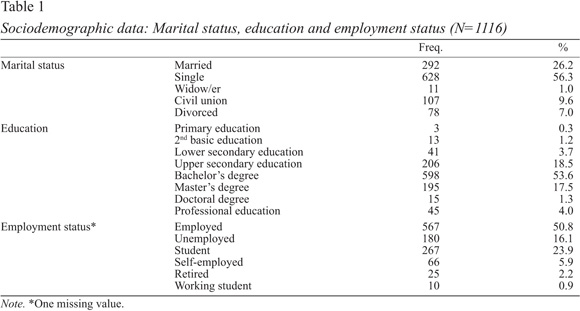

1116 members of the general population took part in the study and agreed to participate in a research protocol called “Humiliation: From actions to damages”, complying with the inclusion criteria – being 18 years of age or older. Of these, 196 (17.6%) were male, Mage=36.29, SDage=14.34, and the remaining 920 (82.4%) were female, Mage=32.23, SDage=10.69. The remaining sociodemographic characteristics were the following: Prevalence of single status, 56%, compared to married and civil partnership, 35.8%. Prevalence of higher education, 72.4%, against other levels of education; Prevalence of employed participants, 56.7%, on students and working students, 24.8%, and on pensioners, 2.2% (Table 1).

Instruments

The HI, original version, is composed of 32 items that must be rated on a five-interval Likert scale, from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always), the latter corresponding to the greatest degree of experienced humiliation. The inventory is divided into four sections: The first section is composed of 12 items and aims to identify the severity with which the individuals felt affected by a given life event (“Throughout your life how seriously have you felt harmed by being…, e.g., scorned?”); The second section intends to assess the fear of being the object of humiliating behaviour (“At this point in your life, how much do you fear being…, e.g., laughed at?” (items 13 to 23); The third section intends to assess concerns, “At this point in your life, how concerned are you about being, e.g., discounted as a person?” (items 24 to 30), and the fourth section aims to assess worries, “How worried are you about being… e.g., inadequate?” (items 31 and 32).

After an exploratory factor analysis was applied, with an eigenvalue <1 and oblimin rotation (item-total correlation >.50; factors loading ≥.60 and ≤.2 in a second factor), two factors were retrieved: items 1 to 12 (factor 1), called “cumulative humiliation”, Cronbach’s alpha=.95, M=32, SD=10; and items 13 to 32 (factor 2), called “fear of humiliation”, Cronbach’s alpha=.94, M=46, SD=17. The total HI score was also conceptualised as a measure to be considered, Cronbach’s Alpha=.96; M=78, DP=25. This exploratory study was carried out using 253 respondents – primarily university students, Mage=20.66, SD=5.06 – from different educational institutions in the United States.

Procedure

The original version was independently translated by the first two authors and by an external collaborator, an expert in the English language familiar with both cultures (The author of the original scale did not participate directly in the development of the translation but as an adviser); subsequently, both versions were compared, gathering great consensus, and the final version was formed unanimously. The only problematic issue was related to the translation of the vernacular word “fear” in the phrase “How much do you fear being…”. Should it be translated by “medo” or by “receio”, a word of the same emotional category? Consensually, we opted for the expression “receio” instead of “medo”, the direct equivalent of fear, with the purpose of, by semantic approximation, grasping both factors, according to the original inventory. This theme will be addressed once again in the discussion.

After that, the HI-Portuguese was integrated into a more extensive research protocol which was submitted to a pre-test, in a class of 56 university students. Afterward, these respondents were debriefing about the understanding of the items, including the translation issue previously mentioned, the time needed for completing the protocol, and the level of fatigue experienced by respondents. The students’ comments were all favourable to proceed.

Data collection: The HI-Portuguese and the respective informed consent were made available online, via the Google Docs platform, with links being shared on several social media websites – Facebook, Linkedin – and higher education institutions. Answers were automatically stored in the Google Docs database that only the researchers had access to. At the end of the research protocol, participants were asked to express their opinions as well as the difficulties and doubts they had experienced during completion of the questionnaires. These questions aimed to qualitatively assess the reliability of completion. Only three respondents claimed it was “long”, without any other issues being highlighted.

For statistical analysis, we applied the SPSS-23/AMOS, and R-software. The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Platform: x86_64-apple-darwin15.6.0 (64-bit), and Lavaan package (Rosseell, 2018).

Ethical Considerations. The research was approved by the ethics committee of the institution of the first authors (Doc 16/CE/2017). The filling protocol featured an informed consent at the beginning, explaining the objectives, filling conditions, identification of the institution and contact information of the researchers. The data were collected anonymously.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for the two-factor model

We applied the two-factor model test to the HI-Portuguese, using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In previous analysis, no outliers had been identified (Mahalanobis distance – p1 and p2<.001) and the values of skewness and kurtosis indicate an univariate normal distribution, |Sk|<3 and |Ku|<7, as suggested by Kline (2016); notwithstanding, given that the observed critical value (of 478,546) – equivalent to Mardia’s standardised coefficient – may indicate a possible violation of the assumption of the multivariate normal distribution since it is higher than 5 (Byrne 2010), we opted for the asymptotic distribution-free (ADF) method; we were able to apply it because the sample was higher than 1000 individuals and because the proportion of 10 subjects per parameter to be estimated was maintained. Reference values for the analysis of the quality of fit were taken from Marôco (2014), Brown (2006), and Schumacker and Lomax (2004): χ2/gl<5 e p<.05; comparative fit index (CFI), goodness of fit index (GFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI)≥0.95; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA)≤.05, with CI (90%), and SRMSR<.05.

All variables had high saturations (λ≥0.5) and adequate reliability (R2>.25). Nevertheless, the goodness of fit indexes obtained failed to prove the model (χ2=4.78, p<.05; CFI=0.75; GFI=0.84; RMSEA=.058, p<.01). Modification indexes (MI) point towards the existence of several correlations between errors. Subsequently, we carried out two model modifications that resulted in an increased correlation between errors (between 10 pairs of errors). Regarding fit indicators from the final model, only the χ2/gl and RMSEA ratio feature values that fall within the acceptance range χ2/gl=2.92, p<.05; RMSEA=.041, p(Close)=.99 (χ2=2.92, p<.05; CFI=.88; GFI=.91.

Searching for an alternative model

Factor analysis by the principal component analysis – PCA. The search for an alternative solution was conditioned by observing the non-compliance of the multivariate normal distribution parameters indicated above and because the value of the determinant of the correlation matrix indicates possible multicollinearity, therefore discouraging the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) by the maximum-likelihood estimation method (reference determinant >1E-4; observed determinant=1.99E-15; Haitovsky=5.11291E-12, gl=496; <.000). Therefore, EFA was executed using the “principal component analysis” (PCA) extract method, with direct oblimin rotation (Delta 0), followed by the analysis of the reliability of the HI and its factors, by calculating Alpha Cronbach indexes.

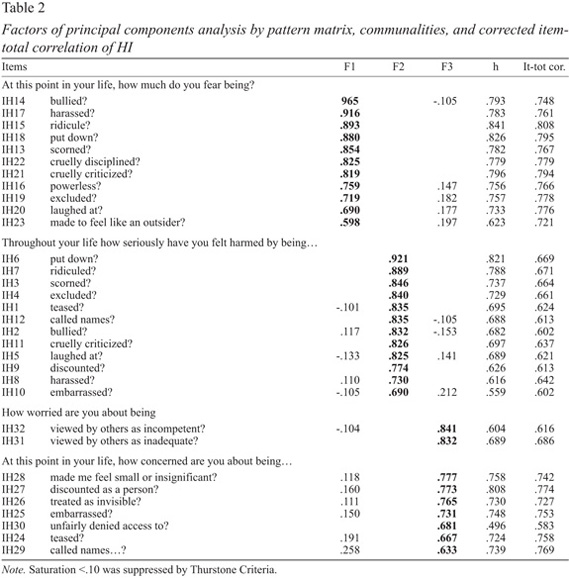

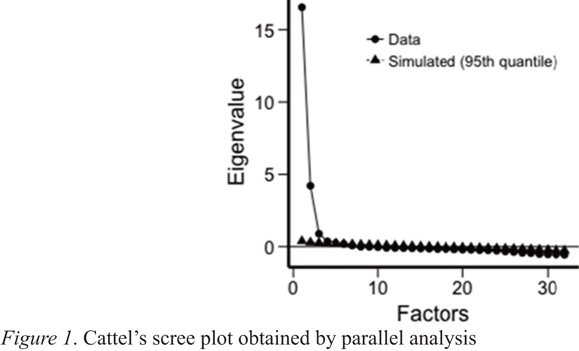

The sample had adequate values (Kaiser, Meyer, Olkin; KMO=.97; individual KMO>.90) and was sufficiently wide enough (Bartlett test=37913.5; gl=496; p<.000) for being executed. The solution presented in Table 2 converged in 8 iteractions and corresponds to a 3-factor solution (Kaiser>1), confirmed by the indication of Cattell’s scree test, obtained by parallel analysis (Figure 1).

The three factors account for approximately 72% of total variance. Therefore, factor 1, fear of humiliation, items 13-23, explains about 53.12% of total variance (eigen value, 16.9), with αCronbach=.97; factor 2, cumulative humiliation, items 1-12, explains about 15% (eigen value, 4.8), with αCronbach=.95, and factor 3, items 24-32, concern/worry about humiliation, explains about 4% (eigen value, 1.3), with αCronbach=.94. The average of commonalities is .72 and varies between .496 and .841. Item saturation varies from .965 and .598 in factor 1; between .921 and .690 in factor 2 and between .841 and .630 in factor 3. In turn, bivariate correlations between factors and between total inventory and factors are as follows: F1-12=>F13-23=.506, F13-23=>F24-32=.83, F1-12=>F24-32=.486, IHtot32it=>F1-12=.87, F13-23=.86; F24-32=.754. There were no crossed items worthy of registration, because the greater saturation of an item in the competing factor (F1), specifically item 29, is .258, being .633 in the belonging factor (F3); which corresponds to a difference of .375 units.

Confirmatory factor analysis for the three-factor model

Following the PCA indicators and to fully understand the structure of the measure we completed the CFA for a three-factor model with R-software: Lavaan package, robust methods-MLM estimator (Yves Rosseel, 2018), with Satorra-Bentler (S-B) scaling correction factor=1.513. The CFA produced a model that may be considered to have an acceptable fit: χ2(461)=2780.970, χ2/df=6.03, p=.000, CFI=.934, TLI=.929, SRMSR=.036; with the contrariety of RMSEA being of .067, CI [.065, .069], p=.000 and the χ2/df>5 ratio. Moreover, the current model does not report discriminant validity between the second and the third factor, although it presents good values for all other parameters: Factorial validity, λ>.50, between .66 e .91; Composite reliability, F1=.959, F2=.970, F3=.947, and average variance extracted – AVE, F1=.662, F2=.746, F3=.662, granting it convergent and discriminant validity between F1<=>F2, R2=.265, F1<=>F3, R2=.498, but not between F2<=>F3, R2=.745.

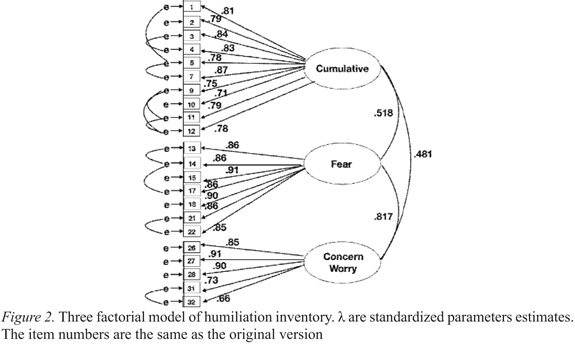

Although the 32-item model could be considered acceptable with a broad criterion, we studied the possibility of increment verifying modification indexes (MI) and expected parameters change (EPC). We took into consideration the indication of covariance between errors of the same factor and suppressed the items related to covariance of inter-factor errors, respectively in the following factors: Cumulative humiliation (CumH), items 6, 8; Fear of humiliation (FH), items 16, 19, 20; Concern/Worry about humiliation (C/W H), items 24, 25, 29, 30. For the model that resulted from this respecification, very good fit indexes were verified: S-Bscaling correction factor=1.416, χ2(196)=570.766, χ2/df=2.91, CFI=.984, TLI=.981, RMSEA=.041, CI[.038, .045], SRMR=.028 (Figure 2).

Construct validity for the respecified model. The three-factor model of the HI, reduced version, has good reliability and construct validity, respectively: Composite reliability (CR>.70, cutoff point) of .947 for ‘CumH’, of .959 for ‘FH’ and of .911 for ‘C/W H’; factorial validity (λ>.50, cutoff point) between .66 and .91; Convergent validity (average variance extracted, AVE>.50, cutoff point), and discriminant validity (AVE>R2, square of the correlation between factors): AVECum=.64>R2Cum_F=.268; >R2Cum_C/W=.231; AVEF=.77>R2F_C/W=667<AVEC/W=.68.

Descriptive values. The three-factor model has the following structure and descriptive values: Cumulative humiliation factor (CH), 10 items, Mtotal=30.51; SDtotal=11.17, αCronbach=.94; fear factor (FH), 7 items, Mtotal=15.68, SDtotal=8.42, αCronbach=.96; and concern/worry factor (C/WH), 5 items, Mtotal=12.18, SDtotal=6.07, αCronbach=.91. Global Humiliation Inventory (22 items), M=58.37, SD=21.58, αCronbach=.956.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to create a Portuguese version the HI and verify whether or not the two-factor model found in the original research fit in a study of a Portuguese population. Using this assessment instrument with this population may provide insights on humiliation, an important phenomenon resulting from relations, both personal and institutional, which may cause severe psychological damage.

The linguistic adaptation was analysed and discussed between the two native Portuguese-speaking researchers and a specialist who is a native English speaker and familiar with the Portuguese language and culture. This will have conferred a good understanding of the study by participants, evaluated both during the pre-test phase and during the study itself. Notwithstanding, the two-factor model, as analysed by the CFA, failed to fully explain the data correlation matrix observed. Furthermore, successive modifications produced a considerable increase in correlations between errors without reaching a joint fit of the adopted indicators as regularly advised (Brown, 2006; Marôco, 2014). Due to the setback of the increase in the number of correlations between errors sharing the variance explained (Brown, 2006), we opted to search for an alternative model.

We first searched for an alternative model, as explained earlier, using the PCA, which produced a three-factor solution, differing in number and order of extraction and with a good reliability, considering as global measurement. Furthermore, the CFA proved a tri-factorial solution with an excellent adjustment, considering the twenty-two items with the advantage of registering factorial, convergent and discriminant validity.

Our explanation for the emergence of a third factor lies within the cultural and linguistic aspects linked to the different understanding of the questions of the second and third sections. The second section is led by the expression-emotion fear, which was translated as receio, an instance or subcategory – following prototypical analysis – of the emotional category of fear, but of low intensity (Cardoso, 2008); in turn, the third and fourth sections are spearheaded by the terms concern and worried respectively and were translated as preocupar (praecupare, lat.), which echoed in the expression “to become apprehensive” (Cândido Figueiredo Dictionary). Furthermore, one should note that, for Portuguese people, concern and worry – preocupação – refers to the cognitive aspect of persistent and recurrent thinking, being semantically distant from fear. In short, being concerned or worried may contain a residual fear, but not an intense fear; and, perhaps due to this, was important enough to cause its appearance as a latent variable among the participants of the Portuguese sample. Hence, forcing a solution to converge into two factors would obscure a highly important latent variable: ‘concern/worry about humiliation.’ In addition, recurrent and persistent ‘concern/worry’ may stand out in some clinical settings and prove to be an important factor contributing to the disturbance of psychological wellbeing.

The second reason may be related to the sociodemographic differences between the American and Portuguese samples. The original study was carried out primarily with students from American university settings, while the adaptation study was carried out with a sample that encompasses both university students and the general population, thus rising the average age. There may also be differences among the participants of both samples, relating to their personal history of fears and concerns regarding the phenomenon under study.

The imbalance in the number of participants per gender is a problem we have experienced, which is increasingly identified as a problem in other studies. This issue, in fact, deserves a research study of its own. The failure to obtain parameters that would have allowed for the use of inferential analyses was another obstacle, having turned to PCA, an analysis that does not produce inferences for the population. In future research, we hope to be able to overcome these constraints, as well as to assess the predictive power of the inventory regarding clinical variables.

Two versions of the HI have been published recently, confirming and disconfirming the original version. A Korean version (Lee & Shin, 2018) rejected the two-factor solution, putting forward a three-factor model adjusted in a sample of 253 respondents of the general population. The authors justify the emergence of the third factor also due to cultural distinctions, such as the high competitiveness among the Korean people, which would explain the distinction between “fear of humiliation” and “humiliation of incompetence.” This is the reason why the third factor was termed “humiliation of incompetence”, composed of items 31 and 32. In fact, these items relate to this semantical relation: “viewed by others as inadequate” and “viewed by others as incompetent”.

Notwithstanding, we consider that the name “worry humiliation” might be more appropriate, since it relates better to the context created by the question: “How worried are you about being...”. Thus, the connection with the original version would be more precise, as well as with the Portuguese version we presented. Another consideration that should be underlined is the adjustment degree, since the indexes reported may only be acceptable by wide criteria, contrary to our version.

For their part, applying an exploratory factor analysis, Numata, Yutaka and Hartling (2016) reported a Japanese version confirming the two-factor model.

We must emphasise that, while a growing body of research suggests that humiliation is a universal human experience, it is an experience that is deeply influenced by the cultural context, involving many aspects such as internal experiences, external interactions, and systemic conditions (Hartling & Lindner, 2017). Thus, in addition to the explanations above, it is not surprising to us that our adaptation has a different solution than the original. Notwithstanding, we also consider that, in the future, contributions should be made towards the search for psychological invariants, expressed by latent variables, in order to offer inputs to the universal study of humiliation: as a personal experience and as a result of offensive social interaction. So, besides the application of the item response theory (IRT), we expect the publication of other results, as well as the collaborative implementation of procedures that lead to the analysis of the invariance of factors – with big data – across different nationalities, and the application of multitrait-multimethod methodologies with multiple groups.

In summary, the Portuguese reduced version of the HI consists of three factors: the “cumulative humiliation” (CH) factor comprising items 1, 2, 3, 4 , 5, 7, 9, 10, 11 and 12 (excluded items: 6 and 8) and matches the original factor (section I of the inventory); the “fear of humiliation” factor, comprising items 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 21, 22 (excluded items: 16, 19, and 20) corresponding of the original “fear of humiliation” factor (half of section II of inventory); and, finally, the “concern/worry about humiliation” factor, which encompasses items 26, 27, 28, 31, 32, and corresponds to sections 3 and 4 of the questionnaire, integrating factor 2 of the original version (excluded items: 24, 25, 29, 30).

This version might offer a significant contribution to nomothetic studies. However, one must remember that the 32-item version reported acceptable adjustment indexes and that it might be taken as a global and alternative measurement, provided that the psychometric values specific to the ongoing researches allow this. For example, different studies have been conducted using it as a global measurement with satisfactory results regarding clinical variables (Collazzoni et al., 2014), non-clinical individuals (Rudgiero, Veronese, Castiglioni, Procaccia, & Sassaroli, 2017), and into institutional contexts with immigrant populations (Janicka, 2009). Similarly, it may have an ideographic application because it elicits a greater diversity of reactions (Hartling, 1996).

In conclusion, we consider this study puts forward good solutions to the extent that it maintains the measures of the original version and adds the concern/worry about being humiliated as a discriminant measure related to humiliation.

With this instrument, our intention is to offer a support that extends the global study of humiliation as it increasingly gathers more attention, be it from researchers, scholars, doctors, or policy-makers. By creating effective assessment tools for examining the impact of this experience, we can formulate effective ways to address the actions and conditions that foster humiliation in different cultures, thus, fostering the healthy growth and development of individuals while strengthening conditions that lead to conviviality between individuals from the same and different cultures.

References

Brown, T. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York and London: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Byrne, B. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). New York and London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cardoso, F. (2008). Estrutura e dinâmica do sistema afectivo das dimensões de avaliação às estruturas de ação: Emoções (Structure and dynamic of affective system: From dimensions of evaluation to structures of action: Emotions). Doctoral dissertation. Retrieved from http://repositorio.utad.pt/handle/10348/106 [ Links ]

Cardoso, F. (2015). Social regulation of emotion: A foray into the work of Catherine Lutz. Revista E-Psi, 5, 103-109. [ Links ]

Cohen, T. (2017). The morality factor. Scientific American-Mind, 28, 32-38. [ Links ]

Collazzoni, A., Capanna, C., Bustini, M., Marucci, C., Prescenzo, S., Ragusa, M., . . . Rossi, A. (2015). A comparison of humiliation measurement in a depressive versus non-clinical sample: A possible clinical utility. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71, 1218-1224. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22212 [ Links ]

Collazzoni, A., Capanna, C., Bustini, M., Stratta, P., Ragusa, M., Marino, A., & Rossi, A. (2014). Humiliation and interpersonal sensitivity in depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 167, 224-227. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.008 [ Links ]

Cushman, P. (1995). Constructing the self, constructing America: A cultural history of psychotherapy. Garden City, New York: Da Capo Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), Oxford handbook of human motivation (pp. 85-107). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.001.0001 [ Links ]

Fernández, S., Saguy, T., & Halperin, E. (2015). The paradox of humiliation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41, 976-988. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215586195 [ Links ]

Fineman, M. A. (2004). The myth of autonomy: A theory of dependency. New York: New Press. [ Links ]

Frevert, U. (2016). The history of emotions. In L. F. Barrett, M. Lewis, & J. Havilland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (4th ed., pp. 49-65). New York and London: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Gilbert, P. (2003). Evolution, social roles, and the differences in shame and guilt. Social Research, 70, 1205-1230. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40971967 [ Links ]

Gilbert, P. (2010). The compassionate mind. London: Constable & Robinson Ltd. [ Links ]

Hartling, L. M. (1996). Humiliation: Assessing the specter of derision, degradation, and debasement. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Union Institute, Cincinnati, USA. [ Links ]

Hartling, L. M. (2007). Humiliation: Real pain, a pathway to violence. RBSE – Brazilian Journal of Sociology of Emotion, 6, 466-479.

Hartling, L. M., & Lindner, E. G. (2016). Healing humiliation: From reaction to creative action. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94, 383-390. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12096 [ Links ]

Hartling, L. M., & Lindner, E. G. (2017). Toward a globally informed psychology of humiliation: Comment on McCauley. American Psychologist, 72, 705-706. [ Links ]

Hartling, L. M., Lindner, E. G., Spalthoff, U., & Britton, M. (2013). Humiliation: A nuclear bomb of emotions?. Psicología Política, 46, 55-76. [ Links ]

Hartling, L. M., & Luchetta, T. (1999). Humiliation: Assessing the impact of derision, degradation, and debasement. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 19, 259-278. doi: 10.1023/A:102262242251 [ Links ]

Heidegger, M. (2010). Being and time [Sein und zeit] (Joan Stambaugh, trans.). Albany, New York: University of New York Press. (original work publ. in 1927) [ Links ]

Hollin, C. (2016). The psychology of interpersonal violence. Chichester, West Sussex, UK and Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [ Links ]

Janicka, A. (2009). Humiliation in labor immigration. Doctoral dissertation (prepared under the supervision of Marek Okólski), University of Warsaw. Retrieved from https://depot.ceon.pl/bitstream/handle/123456789/1313/Anna%20Janicka_shalm_intro_biblio.pdf?sequence=1 [ Links ]

Jogdand, Y., & Sinha, C. (2015). Can leaders transform humiliation into a creative force?. Journal of Leadership Studies, 9, 75-77. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1002/jls.21413 [ Links ]

Jordan, J. V., & Hartling, L. M. (2002). New developments in relational-cultural theory. In M. Ballou & L. S. Brown (Eds.), Rethinking mental health and disorders: Feminist perspectives (pp. 48-70). New York: Guilford Publications. [ Links ]

Jordan, J. V., Walker, M., & Hartling, L. M. (Eds.). (2004). The complexity of connection: Writings from the Stone Center’s Jean Baker Miller Training Institute. New York: Guilford Press.

Kendler, K., Hettema, J., Butera, F., Gardner, C., & Prescott, C. (2003). Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Archive General Psychiatry, 60, 789-796. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.789x [ Links ]

Klein, D. C. (1991). The humiliation dynamic: An overview. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 12, 93-121. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1007/BF02015214 [ Links ]

Kline, R. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York and London: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford Press. [ Links ]

Leask, P. (2013). Losing trust in the world: Humiliation and its consequences. Psychodynamic Practice, 19, 129-142. doi: 10.1080/14753634.2013.778485 [ Links ]

Lee, S., & Shin, H. (2018). Validation of the Korean version of the Humiliation Inventory. Korean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 37, 119-129. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.15842/kjcp.2018.37.1.010 [ Links ]

Leidner, B., Sheikh, H., & Ginges, J. (2012). Affective dimensions of intergroup humiliation. PLoS ONE, 7(9). [ Links ] Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046375

Lewis, M. (2016a). Self-Conscious emotions: Embarrassment, pride, shame, guilt, and hubris. In L. F. Barrett, M. Lewis, & J. Havilland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (4th ed., Cap. 45). New York and London: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Lewis, M. (2016b). The emergence of human emotions. In L. F. Barrett, M. Lewis, & J. Havilland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (4th ed., Cap. 15). New York and London: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Lindner, E. G. (2010). Gender, humiliation, and global security: Dignifying relationships from love, sex, and parenthood to world affairs. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. [ Links ]

Lindner, E. G. (2013). Emotion and conflict: Why it is important to understand how emotions affect conflict and how conflict affects emotions. In D. Morton, P. Coleman, & E. Marcus (Eds.), The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Marôco, J. (2014). Análise de equações estruturais. Fundamentos teóricos, software e aplicações [Structural equations analysis: Theoretical foundations, software, and applications] (2nd ed.). Lisboa: ReportNumber. [ Links ]

Miranda-Santos, A. (1972). Expressividade e personalidade. Um século de psicologia [Expressivity and personality: A century of psychology]. Coimbra: Atlântida. [ Links ]

Negrão, C., Bonanno, G. A., Noll, J. G., Putnam, F. W., & Trickett, P. K. (2005). Shame, humiliation, and childhood sexual abuse: Distinct contributions and emotional coherence. Child Maltreatment, 10, 350-363. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1177/1077559505279366 [ Links ]

Numata, M., Matsui, Y., & Hartling, L. M. (2016). Development of the Japanese version of the Humiliation Inventory (HI-J). International Journal of Psychology, 5, 550. [ Links ]

Rosseel, Y. (2018, Jul, 20). The lavaan tutorial. Belgium: Department of Data Analysis, Ghent University. Retrieved from http://lavaan.ugent.be/tutorial/tutorial.pdf [ Links ]

Ruggiero, G. M., Veronese, G., Castiglioni, M., Procaccia, R., & Sassaroli, S. (2017). Cognitive avoidance, humiliation, and narcissism in non-clinical individuals: An experimental study. In A. Collumbus (Ed.), Advances in psychology research (Vol. 128, pp. 1-16). New York: Nova Science Publisher. [ Links ]

Ryan, T. (2017). The positive function of shame: Moral and spiritual perspectives. In E. Vanderheiden & C.-H. Mayer (Eds.), The value of shame, exploring a health resource in cultural contexts (pp. 87-108). Switzerland: Springer. [ Links ]

Schumacker, R., & Lomax, R. (2004). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Laurence Earlbaum.

Silfver-Kuhalampi, M., Figueiredo, A., Sortheix, F., & Fontaine, J. (2015). Humiliated self, bad self or bad behavior? The relations between moral emotional appraisals and moral motivation. Journal of Moral Education, 126, 1-19. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2015.1043874 [ Links ]

Stets, J. E., & Trettevik, R. (2014). Emotions in identity theory. In J. E. Stets & J. H. Turner (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of emotions (Vol. II, pp. 33-49). New York and London: Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9130-4_3 [ Links ]

Torres, W. J., & Bergner, R. M. (2010). Humiliation: Its nature and consequences. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 38, 195-204. [ Links ]

Van Alphen, M. (2017). Shame as a functional and adaptive emotion: A biopsychosocial perspective. In E. Vanderheiden & C.-H. Mayer (Eds.), The value of shame, exploring a health resource in cultural contexts (pp. 61-86). Switzerland: Springer. [ Links ]

Vanderheiden, E., & Mayer, C. (2017). An introduction to the value of shame. In E. Vanderheiden & C.-H. Mayer (Eds.), The value of shame, exploring a health resource in cultural contexts (pp. 1-42). Switzerland: Springer. [ Links ]

Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23, 263-280. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1037/a0032359 [ Links ]

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Francisco M. S. Cardoso, Laboratório de Psicologia Experimental Clínica, UTAD – Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Quinta de Prados, 5001-801 Vila Real, Portugal. E-mail: fcardoso@utad.pt

Submitted: 01/08/2017 Accepted: 21/09/2018