Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Análise Psicológica

versión impresa ISSN 0870-8231versión On-line ISSN 1646-6020

Aná. Psicológica vol.35 no.4 Lisboa dic. 2017

https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1451

Father’s involvement and parenting styles in Portuguese families: The role of education and working hours

Lígia Monteiro*1, Marília Fernandes*2, Nuno Torres2, Carolina Santos3

1ISCTE – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, CIS-IUL

2William James Center for Research, ISPA – Instituto Universitário

3University of St. Andrews, School of Psychology and Neuroscience, Scotland, UK

ABSTRACT

Early studies on fathers focused mainly on their presence in or absence from children’s lives, and the amount of time they spent with them. More recently, several authors have stated the importance of understanding the quality of father involvement to comprehend fully its impact on child development. However, studies have also reported that socio-demographic variables, namely, father educational levels and employment status affect parenting and children outcomes. The aims of this study were to analyze a sample of 465 Portuguese two-parent families with pre-school age children, looking for associations between father involvement in care/socialization activities and paternal parenting styles while testing for the moderating effect of father educational levels and working hours. Fathers reported on their own parenting styles and mothers described the father’s involvement. Fathers’ working hours moderated the relation between his authoritative parenting style and involvement in teaching/discipline and play activities. In addition, fathers’ education moderated the relation between his authoritative style and involvement in direct care and teaching/discipline. Given the different roles that fathers can assume in their children’s lives, it is important to understand the mechanisms of paternal participation, and identify the factors which explain the differences in effective care so that we can promote higher positive involvement.

Key words: Father involvement, Parenting styles, Working hours, Education.

RESUMO

Os primeiros trabalhos sobre o Pai focavam-se, essencialmente, na sua presença ou ausência da vida da criança e na quantidade de tempo que este passava com ela. Mais recentemente, diversos autores têm salientado a importância de se analisar a qualidade do envolvimento paterno, no sentido de se compreender qual o seu impacto no desenvolvimento infantil. Os estudos têm, ainda, reportado que o nível educativo e o número de horas que os pais trabalham influenciam a parentalidade e os outcomes da criança. Os objectivos, deste estudo, foram analisar, numa amostra de 465 famílias nucleares portuguesas, com crianças em idade pré-escolar, as associações entre o envolvimento do pai nas atividades de cuidados/socialização e os estilos parentais, testando os efeitos moderadores da educação e do número de horas de trabalho. Os pais descreveram os seus próprios estilos parentais e as mães o envolvimento paterno. As horas de trabalho moderam a relação entre o estilo autoritativo do pai e o seu envolvimento nas atividades de ensino/disciplina e nas atividades de brincadeira. Adicionalmente, o nível educativo dos pais modera a relação entre o seu estilo autoritativo e o envolvimento nos cuidados diretos e ensino/disciplina. Dado os diferentes papéis que os pais podem assumir na vida dos filhos, é importante compreender os mecanismos relativos ao seu envolvimento e identificar os factores que explicam as diferenças num cuidado adequado, no sentido de se promover um envolvimento paterno elevado, quantitativa e qualitativamente.

Palavras-chave: Envolvimento paterno, Estilos parentais, Horas de trabalho, Educação.

Like most of Southern Europe, Portugal has until recently espoused family life that was clearly organized by gender differentiation with man as the main, or even sole, economic provider, and women as primary caregivers, with family organization as their central roles (Aboim, 2010). In the last few decades the gender dynamics and familial roles have shifted; principally due to political and economic changes, with increased participation of women in the workforce outside of the home (Cabrera, Tamis-LeMonda, Bradley, Hofferth, & Lamb, 2000). Although the traditional ‘male breadwinner and housewife’ dichotomy remains a Portuguese family pattern, it is no longer viewed as the ideal, being often associated with low educational levels and lack of employment opportunities (Escobedo & Wall, 2015). It should be noted that Portugal is one of the EU countries with the highest number of women with preschool aged children who are working full time outside of the home (Aboim, 2010). In this context and with progressive change on how gender roles are perceived (women as having fulfilling careers and men as able caregivers) it has become the “new modern” to share economic, as well as domestic and parental responsibilities (e.g., Cabrera, Shannon, Mitchell, & West, 2009; Raley, Bianchi, & Wang, 2012). Portuguese welfare policies have been promoting a dual breadwinner model, although men’s involvement in caring is quite recent (Aboim, 2010). According to Wall (2010), in Portugal, this view on parenting has been framed, since 1995, by new policies in parental leave. However, it was only in 2009 that ‘Maternity Leave’ was replaced by ‘Initial Parental Leave’, the five day Paternity leave replaced by ‘Fathers-Only Parental Leave’ (10 mandatory plus, 10 optional days) and a ‘Sharing Bonus’ introduced (shared leave increased from .5% in 2005 to 26.1% in 2014) (Wall & Leitão, 2015). Another way of supporting father involvement is the policy related to Flexible Working Hours, parents are entitled to two hours ‘nursing’ leave per day during the first year after birth and four hours leave per school term until children reach 18 years of age. Parents with children under 12 years may choose when to start and finish daily work, as long as the normal weekly hours of work are fulfilled; one of the parents (or both for alternative periods of time) is entitled to part-time work after taking Additional Parental leave that can be extended up to two years (Wall & Leitão, 2015). Portuguese leave policy implies an early return to full-time work model, supporting full-time dual earner parents and associated higher levels of maternal employment rates and growing availability of full-time day care services (Escobedo & Wall, 2015).

Like other European and North American countries, caregiving is a newer domain in which men actively participate, and when compared to motherhood, parenthood is culturally less well defined. Several studies show that fathers are less involved in engagement activities than mothers (Craig, 2006; McBride & Mills, 1993). In Portuguese two-parent families, studies show that mothers are more involved in caregiving as well as in play, and seem to be more sensitive during interactions, when compared to fathers (e.g., Fuertes, Faria, Beeghly, & Lopes-dos-Santos, 2016). However, others studies have shown that, although less involved in childcare, and particularly in family management; fathers are just as active in play, teaching/discipline and outdoor leisure activities (e.g., Monteiro, Fernandes, et al., 2010; Torres, Veríssimo, Monteiro, Ribeiro, & Santos, 2014; Torres, Veríssimo, Monteiro, & Santos, 2012).

These progressive changes regarding fathers’ roles should have implications for father-child interactions and on child development (Coyl, Newland, & Freeman, 2010; Craig, 2006; Finley & Schwartz, 2006; Parke, 2002, 2004). Although initial studies have focused mainly on the presence/absence of fathers and how much time they spent with their children, while this data is fundamental, it is critical to also capture the quality of these interactions and involvement (Brown, McBride, Shin, & Bost, 2007; Coyl-Shepherd, & Newland, 2013; Tremblay & Pierce, 2011). Father involvement should, therefore, be understood as a complex and multidimensional construct, that comprises behaviors, emotions and cognitions (Hawkins & Palkovitz, 1999), and different contexts of interaction (e.g., care or play) (Parke, 1996).

One way of studying individual differences in parenting is to focus on parenting styles defined as a set of attitudes towards the child, creating an emotional climate, and where parenting practices occur (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Baumrind’s typology included the Authoritative style characterized by emotional supportiveness, limit setting and firm, yet responsive disciplinary strategies. Parents are flexible and responsive to their children’s needs, make reasonable demands, encourage verbal communication, and frequently explain the reasoning behind their demands in a supportive and nurturing manner (Baumrind, 1971). The Authoritarian style is characterized by high levels of control and discipline, and limited emotional support or responsiveness. Obedience is valued and parents adopt punitive or vigorous measures to enforce demands (Baumrind, 1971). Finally, high levels of emotional support/responsiveness and low levels of discipline/control characterize the Permissive style. These parents are extremely benevolent regarding discipline, although they are responsive to their child’s needs, they do not set appropriate limits on their behaviors (Baumrind, 1971). Although differences can be found considering culture and socioeconomically backgrounds, generally empirical studies tend to show that authoritative parenting has more positive outcomes for children’s emotional, social and academic development, when compared with the authoritarian or permissive styles (e.g., Coplan, Hastings, Lagacé-Séguin, & Moulton, 2002; Fabes, Leonard, Kupanoff, & Martin, 2001; Ferguson, 2013; Lagacé-Séguin & Coplan, 2005; Lamborn, Mounts, Steinberg, & Dornbusch, 1991; Shaw, Krause, Chatters, Connell, & Ingersoll-Dayton, 2004; Steinberg, 2001).

Analysis of parenting styles by gender has shown that fathers tend to display a more authoritarian or permissive style while mothers tend to adopt a more authoritative one (e.g., Russell et al., 1998). In a Portuguese study, mothers described themselves as being more authoritative, compared to fathers and no differences were found for the permissive and authoritarian styles (Pedro, Carapito, & Ribeiro, 2015). When considering their own and spousal parenting styles fathers perceive their wives as more authoritative and permissive, and less authoritarian than themselves, whereas mothers only perceived themselves to be more authoritative than fathers (Winsler, Madigan, & Aquilino, 2005). Other studies suggest that mothers tend to be affectionate and supportive when compared to fathers (e.g., McKinney & Renk, 2008; Oliva, Parra, Sánchez-Queija, & López, 2007; Simons & Conger, 2007). Fathers authoritarian style and mothers attitudes towards parenting and child relate to how responsibilities are shared within families and may be related to how much fathers have become directly involved in the care of their infants (Gaertner, Spinrad, Eisenberg, & Greving, 2007).

Given the growing trend of fathers becoming more involved in child rearing and the potential positive outcomes for children, we need to understand in more detail father-child rearing activities; i.e., how much time do fathers spend, what are they doing during this time, and above all the quality of that involvement. Arsénio and Santos (2013) found in a sample of parents with school age children, that father involvement in care was associated with an authoritative parenting style, while father involvement in the discipline domain was associated with authoritative or authoritarian styles, both based on a high level of demand for the child (Maccoby & Martin, 1983).

Parenting is directly influenced by several variables, fathers’ education and employment status being two of them (Cabrera, Fitzgerald, Bradley & Roggman, 2007; Lamb & Lewis, 2010; Palkovitz, 2002; Yeung, Sandberg, Davis-Kean, & Hofferth, 2001). Fathers with higher education may have more resources; skills or information about child development needs, allowing them to feel secure and motivated to be involved with their children (e.g., Bailey, 1994; Coley & Lansdale, 1999). They could also have less traditional views on gender roles; having been exposed to more egalitarian ideals, thus facilitating the taking of more responsibilities and being more engaged in child care (Jacobs & Kelley, 2006; Marks, Bun, & McHale, 2009). Parke (2002) proposed that fathers with higher education were more satisfied with their jobs, which has been associated with positive perceptions of their role and involvement as parents. On the contrary, limited resources, unstable employment and lower education have a negative impact on how fathers establish/maintain positive and emotionally supportive relationships with their children (e.g., Cabrera et al., 2004; Garfinkel, McLanahan, & Hanson, 1998; Hofferth & Anderson, 2003; Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004). Fathers’ educational level has been positively associated with quality of father-child interaction (Palkovitz, 2002; Yeung et al., 2001), more father participation in play/leisure activities (Monteiro, Veríssimo, Pessoa e Costa, & Pimenta, 2008) and in indirect care (Monteiro, Fernandes, et al., 2010).

Fathers with more demanding jobs tend to spend more hours at work, and consequently a smaller amount of time with their children (Hofferth & Anderson, 2003; Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004). Fernandes, Monteiro e Veríssimo (2015) found in a Portuguese sample that this was true for father involvement across both caregiving and socialization activities. The greater number of hours men worked outside the home, the less responsibility fathers took for childcare. Having less time to be available and engaged in child activities has been negatively associated with father-child interaction and involvement (Jacobs & Kelley, 2006; Lima, 2005; Yeung et al., 2001). More exhausted or stressed parents might adopt a more typical hierarchical parent-child relationship, or alternatively a more permissive or uninvolved style of parenting (Laursen & Collins, 2009; Zaslow et al., 2006).

In Portugal, the overlap between family and career seems to be far more evident for women, since they spend more time planning and executing household activities. By law, Portuguese full-time employees work 35 hours/week, yet women reported spending almost 41hours/week and men around 43 hours/week (Perista et al., 2016). Working women experience more work/family stress than men, yet married men with young children, also report high levels of stress (Wall, 2007). Employment status and working hours are often an argument associated with gender division of labor, with fathers being the primary breadwinner. In dual earner families, mothers’ working hours predicted the amount of responsibility men took for childcare and the percentage of time fathers acted as primary caregiver for their child (Jacobs & Kelley, 2006).

The present study integrates these different domains by examining, in a sample of Portuguese two-parent families, associations among fathers’ involvement in care/socialization activities and parenting styles (as an indicator of quality), while considering the moderating effect of education and working hours.

Method

Participants

Four hundred and sixty-five mothers and fathers, from two-parent families, participated in the study. All couples were either married or cohabiting. The mothers were between 22-46 years (M=35.13; SD=4.47), and fathers’ ages ranged from 21-62 (M=37.14; SD=5.68). Mothers’ education level varied between 4-23 years (M=14.13; SD=3.48) and fathers’ between 4-21 (M=12.50; SD=3.64). In occupational terms, both parents were employed; with mothers working between 15-60 hours/week (M=38.57; SD=5.15), and fathers 25-75 hours/week (M=41.84; SD=6.24). Children were between 26 and 78 months of age (M=54.23; SD=11.75), 50.3% were boys, 63.0% were firstborn, and 59.6% had siblings. All attended day-care programs in the district of Lisbon.

Instruments/Procedures

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association, and approved by the Ethical board of ISCTE-IUL. It is part of a larger research project regarding the implications of paternal involvement in children’s socio-emotional development. All participants were informed of the main goals of the research and signed an informed consent prior to data collection.

The fathers’ involvement was assessed using the Parental Involvement: Care and Socialization Activities scale (Monteiro, Veríssimo, & Pessoa e Costa, 2008). The questionnaire has 26 items regarding the organization and implementation of activities involving parent and child that occur in daily family life. It has five dimensions: (1) Direct Care (5 items) related with caretaking tasks, implying direct contact and interaction with the child (e.g., ‘Who feeds the child’); (2) Indirect Care (7 items) does not necessarily imply interaction, it is related with organizing the resources to be available to the child (e.g., ‘Who usually buys your child clothes’); (3) Teaching/Discipline (5 items) related with teaching skills and rules for the child (e.g., ‘Who teaches the child new skills’); (4) Play (5 items) related with play activities between the child and the parent (e.g., ‘Who plays physical games with the child: football or rough and tumble’); and (5) Outdoor Leisure (4 items) related to activities done with the child outside the home (e.g., ‘Who takes the child to the park’). Participants were asked to answer on a 5-point Likert scale: (1) Always the mother; (2) Nearly always the mother; (3) Both the mother and the father; (4) Nearly always the father; and (5) Always the father. Higher scores represent more father involvement compared to the mother. In this study, mothers described fathers’ behaviors avoiding shared method variance. The Cronbach’s Alpha reached acceptable values for all dimensions: Direct Care .72, Indirect Care .65, Teaching/Discipline .70, Play .67, and Outdoor Leisure .65.

Fathers described their own parenting styles using the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire – PSDQ (Robinson, Mandleco, Olsen, & Hart, 2001; Pedro, Carapito, & Ribeiro, 2015). This short version has 32 items organized in three main dimensions: (1) Authoritative (18 items) characterized by emotional supportiveness, limit setting, and firm yet responsive disciplinary strategies (e.g., I take our child’s desires into account before asking the child to do something); (2) Authoritarian (10 items) described as strong levels of control and limited emotional support or responsiveness (e.g., I use physical punishment as a way of disciplining our child); and (3) Permissive (4 items) defined by high levels of emotional support/responsiveness but slight levels of discipline/control (e.g., I state punishments to our child and do not actually do them). Fathers answered in a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) Never to (5) Always. The measure gives a separate score for each dimension of parenting, higher scores indicate increased use of that particular style. The Cronbach’s Alphas were .78 and .73 respectively. The Permissive dimension did not reach acceptable levels, therefore was not considered for further analyses.

Data analysis plan

Analyses were organized in two steps. First, we conducted bivariate correlations to determine the extent to which fathers’ parenting styles; child age and family characteristics (age, educational level and working hours) were associated with paternal involvement. We also tested for child differences (sex, being firstborn and having siblings) in father involvement.

Additionally, in order to statistically control for the effects of all the variables in the model and estimate the possible effects of the interaction between the father parenting styles and other father related variables we conducted a series of ordinary least squares (OLS) multiple regression analyses. Specifically, we regressed the five father involvement scales on the parenting style, child age, and father characteristics (age, educational level and working hours). For each dependent variable (direct care, indirect care, teaching/discipline, play and leisure) we performed two OLS hierarchical multiple regression analyses using the authoritative parenting style as a predictor in one and authoritarian style as a predictor in the other). The regression models included other paternal variables, as well as the interaction terms between parenting style and father related variables. The variables were entered in the OLS regression models in two hierarchical blocks. The first block was composed of linear relationships: father-level variables (parenting style, fathers’ education and working hours). The second block was composed of the interaction terms of each parenting style with father related attributes (parenting style x father educational level and parenting style x father working hours).

Results

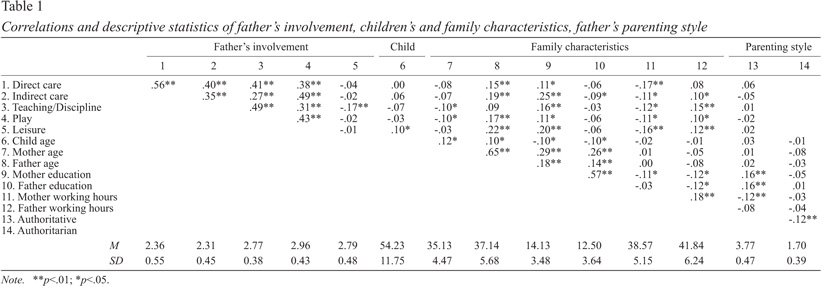

The descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) at the bottom of Table 1 show that fathers were less involved in Care related dimensions. We conducted a one-sample t-test with a 99% confidence interval to determine if the sample means differed significantly from the value of ‘3’ which qualitatively corresponds to ‘both the mother and the father’. The mean values of father involvement were significantly lower than 3 in all dimensions except for Play, so parents were equally involved in Play activities. Stronger differences were in Direct Care (M=2.37, SD=.54), t(445)=-24.52, p<.001, d=1.16, and Indirect Care (M=2.32, SD=.45), t(445)=-32.03, p<.001, d=1.53. A strong difference was also found for Teaching/Discipline (M=2.77, SD=.36), t(445)=-13.39, p<.001, d=0.62. Differences in Outdoor Leisure were moderate (M=2.80, SD=.47), t(445)=-9.22, p<.001, d=0.45. This signifies that mothers were more involved, especially in Care activities.

As we can see in Table 1, there was a negative and significant association between a father’s age and his involvement in Teaching/Discipline and Play dimensions, with older fathers being less involved in these activities. Maternal educational level was positive and significantly associated with all dimensions of father involvement with the exception of Teaching/Discipline. Fathers’ education was positive and significantly correlated with all involvement dimensions, fathers with higher education level seemed to be more involved with their children. Both parents’ education was positively associated with Authoritative paternal parenting style, and there was no association with Authoritarian style. Fathers working hours were significantly and negatively associated with all dimensions of father involvement, fathers with more working hours seemed to be less involved with their children. Looking at the interaction between father involvement and child characteristics, age was only associated with Teaching/Discipline. There was a small effect found related to child birth order; fathers seems to be more involved with firstborns with regard to Indirect Care (M=2.35, SD=.44; M=2.25, SD=.48), t(451)=2.27, p=.02, d=0.22, and Play dimensions (M=2.99, SD=.42; M=2.90, SD=.44), t(451)=2.15, p=.03, d=0.21. Also, fathers participated more when children had no siblings in Indirect care activities (M=2.28, SD=.45; M=2.37, SD=.45), t(461)=2.10, p=.03, d=0.20. However, no sex differences were found.

Finally, all of the father involvement dimensions, except Direct Care, were positive and significantly correlated to Authoritative father parenting style, as we can see in Table 1.

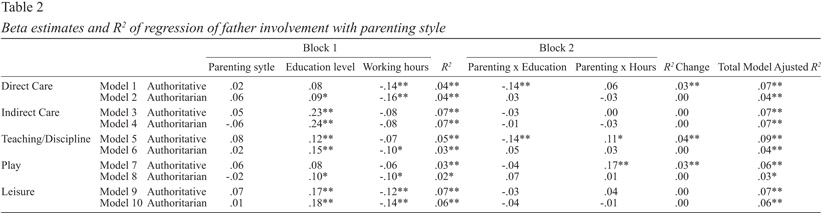

Considering the OLS multiple regressions for father involvement, all models attained a significant amount of explained variance, mostly because of variable contributions of the fathers. Fathers’ educational level had a positive and significant effect in almost all models (except model 1 and 7) while father working hours had a negative and significant effect in all models except 3, 4 and 5.There was no effect of parenting style, as we can see in Table 2.

All models involving Authoritarian parenting style (see model 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10) did not reached significance for block 2, the same happened for Authoritative models 3 and 9, that is, there was no significant interaction between parenting style and fathers’ variables for those models.

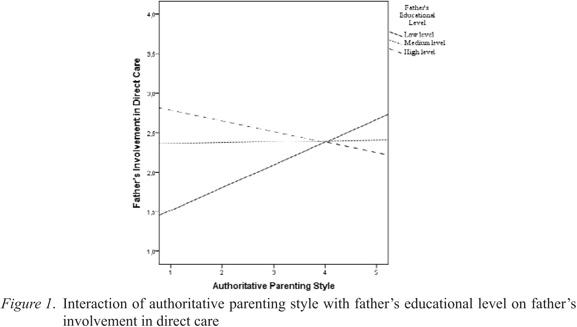

For the Direct Care dimension, model 1, a significant R2 change of .03 was found, F(2,458)=6.81; p=.01, that was due to the significant interaction term of father educational level with fathers having an Authoritative parenting style, β=-0.14, p=.001. This interaction term is illustrated in Figure 1. We transformed the continuous scores of father educational level into a categorical variable with three levels: scores below 12 (Low level, n=143); scores equal to 12 (Medium level, n=169); and scores above 12 (High level, n=152). To further explore the substantive meaning of this interaction term, simple slopes of the regression were tested. High and Medium levels didn’t reach significance, although it was significant for fathers with a Lower educational level, β=0.28, p=.001, that is, for these fathers, it seems that having a more Authoritative parenting style was associated with being more involved in direct care activities.

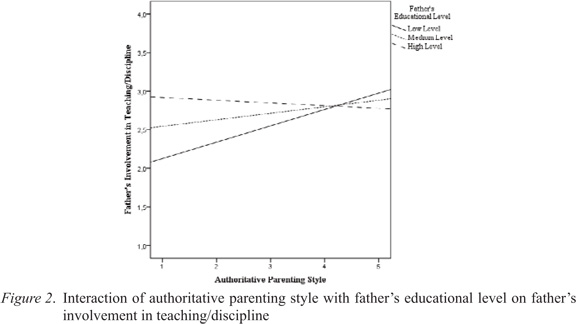

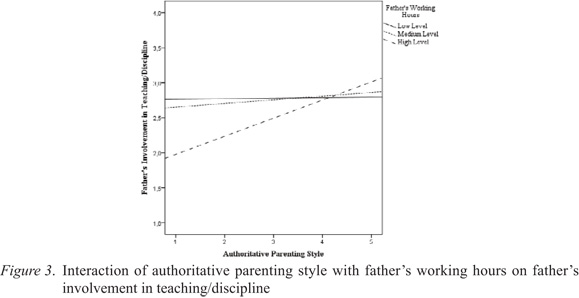

Regarding the Teaching/Discipline dimension; a significant R2 change of .04 was found, F(2,458)=9.37, p<.001. This was due to the significant interaction term of the Authoritative father parenting style with both educational level and working hours, β=-0.14, p=.004 and β=0.11, p=.027, respectively.

These interactions terms are illustrated in Figure 2 and 3. In addition to using the transformed score of father education level we transformed the continuous scores of fathers’ working hours into a categorical variable with three levels: scores below 40 (Low level, n=68); scores equal to 40 (Medium level, n=280); and scores above 40 (High level, n=117). Again, to further explore the meaning of this interaction term, we tested the simple slopes of the regression. High and Medium education levels didn’t reach significance. However interaction was significant for the Lower level, β=0.26, p=.002, that is, for these fathers, it seems that having a more Authoritative parenting style was associated with being more involved in Teaching/Discipline activities.

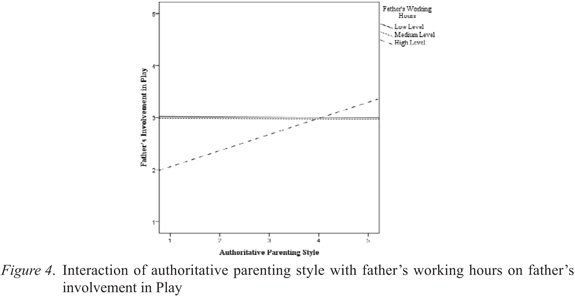

With respect to father working hours, for the sample, Low and Medium working hours didn’t reach significance. For fathers in High category the significance was, β=0.31, p=.001. Meaning that, for fathers who worked more than 40 hours per week, having a more Authoritative parenting style was associated with getting more involved in Teaching/Discipline activities. Likewise, for being involved in Play activities (see model 7), the interaction between father working hours and parenting style was significant, β=0.17, p<.001, R2 change of .03, F(2,458)=8.02, p<.001. These interactions are illustrated in Figure 4.

Furthermore, we tested the simple slopes of the regression of the transformed father working hours. Low and Medium working hours levels, didn’t reach significance. The High working hour level was significant, β=0.32, p<.001, meaning that, for those fathers who worked more than 40 hours per week, having a more Authoritative parenting style was associated with being more involved in Play activities.

Discussion

Today there is a “new ideal of fatherhood” where men are more involved in their children’s lives, not only as breadwinners or play companions, but also as caregivers, a role typically associated with mothers. Although studies have showed that fathers are spending more time with their offspring, compared to previous generations (Bianchi & Milkie, 2010), mothers still seem to be the primary caregivers and fathers the support parent, even in dual-earning families (Gauthier & DeGusti, 2012; Johnson, Li, Kendall, Strazdins, & Jacoby, 2013; Monteiro et al., 2008). Father’s image as more of a play companion seems to find support still in the empirical data (Craig, 2006; Lamb, 2010; Monteiro, Veríssimo, et al., 2010). This was replicated in our study; fathers were less involved than mothers particularly in Direct and Indirect care, but also in Teaching/Discipline and Outdoor Leisure. Only in Play activities were fathers and mothers equally involved. Thus, in this sample, families could still be characterized as more ‘traditional’ regarding gender role organization in child related activities, with fathers spending less time with their children and in a more supportive role, engaging primarily in enjoyable and fun experiences (e.g., Deutsch, 2001; Hwang & Lamb, 1997; Lamb, 2010; Lewis & Lamb, 2003; Monteiro et al., 2008; Torres, Veríssimo, Monteiro, Santos, & Pessoa e Costa, 2013).

Paternal, maternal and child characteristics influence fathers’ involvement (Lamb & Lewis, 2010). The amount and type of father involvement varies in different developmental stages of the child (Lamb, 2010). In our study, as the child got older fathers were less involved in Teaching/Discipline activities, probably associated with children’s developmental gains in emotional and behavior regulation and rules. There was a small effect of childbirth order since fathers were more involved with firstborns (regarding Indirect Care and Play dimensions), and also when children had no siblings (Indirect Care dimension). Having more children may represent less time to interact with each child alone (Harris & Morgan, 1991), but it also might create opportunities for gaining and developing parenting skills, both in play and care, helping parents to be more confidante in their skills (Culp, Schadle, Robinson, & Culp, 2000). Consistent with previous studies with Portuguese preschool children (e.g., Monteiro, Veríssimo, Castro, & Oliveira, 2006; Monteiro, Veríssimo, et al., 2010), there was no significant effects of child sex on fathers’ involvement. These findings are also consistent with a broader review of paternal involvement literature (Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004).

In general, the father’s age has been either insignificant or inversely related to men’s involvement with their children (Pleck, 2010). In our study, older fathers were less involved in Teaching/Discipline and Play activities. In the preschool age, play and leisure activities are central; promoting greater regulation of the child’s behaviors (Monteiro, Fernandes, et al., 2010), this could be a challenge for older parents that may have less energy to get involved (NICHD – Early Child Care Research Network, 2000).

To better understand the impact fathers have on child development we need to address not only their presence or the amount of time they spend with their children, but also the quality of fathers’ involvement (Lamb, 2010), considering that ‘positive engagement’ is a predictor of children’s positive developmental outcomes (Pleck, 2010). If parents aren’t sensible and responsive to child clues, even play activities (usually seen as enjoyable, reciprocal and pleasurable) can be a context for demanding, intrusive or hostile interactions (Brown et al., 2007). In this study, parenting styles were used as “quality” indicator. Fathers perceived themselves as being more Authoritative and less Authoritarian, a result found in other Portuguese samples (e.g., Pedro et al., 2015). And being more Authoritative was associated with greater involvement in all dimensions assessed with the exception of direct care. Authoritative fathers are more responsive to their child’s needs, adopt an open communication and respect their child autonomy while enforcing rules when and if necessary, that might result in a more involved approach (Lamb & Lewis, 2010). We also tested for level education interaction since higher educational level has been associated with a more sensitive and insightful interpretation of the child signs (Fuertes et al., 2009), more time spend in caring and playing activities (Fuertes et al., 2016; Pederson, Gleason, Moran, & Bento, 1998), and more efficient response to child’s requests (Silva, Del Prette, & Del Prette, 2002). On the other hand, less education level may be related to more controlling and interfering actions (Silva et al., 2002). In our study, fathers with higher education levels were the ones perceiving themselves as having a more Authoritative parenting style. And as in other studies (see Pleck, 2010) parent’s education levels were associated with higher father involvement; other Portuguese samples found similar results (Fuertes et al., 2016; Monteiro et al., 2008; Monteiro, Fernandes, et al., 2010; Torres et al., 2013). Higher levels of mother education were related with all dimensions of father involvement except in Teaching/Discipline activities where no association was found. Having a more Authoritative style seems to help those fathers who had lower levels of education be more involved in Direct Care and Teaching/Discipline activities.

Mothers and fathers traditionally describe work constraints as a barrier to greater involvement, and a challenge to balance work and family domains/time. For that reason, fathers’ work hours could be seen as a social contextual influence, in particular as a stressor (Coyl-Shepherd & Newland, 2013; Milkie, Kendig, Nomaguchi, & Denny, 2010). On average fathers in our sample spend nearly 42 hours/week working, and over 25% of the fathers worked more than 40 hours/week in paid labor. The higher the amount of time fathers spent at work the less involved they seemed to be. This may have an impact on parent-child relationship since it potentially reduces chances for parents to be available and engaged with their children, especially during the week. Studies have found that more working hours leads to a decrease of fathers contributing to aspects of daily physical care of the children such as taking children to and from school, bathing, eating dinner, and play (Ishii-Kuntz, Makino, Kato, & Tsuchiya, 2004; Jacobs & Kelley, 2006; Lima, 2005).

More hours at work could lead to more exhausted or stressed parents; and this emotional state has been associated to more hierarchical parent/child relationship (Laursen & Collins, 2009; Zaslow et al., 2006). In our study, although fathers who work more hours tend to be less involved, for those who worked more than 40 hours/week, having a more Authoritative parenting style seems to help them being more involved in Teaching/Discipline and Play activities. Despite having less time to be with their children and spending it in more “traditional domains”, they still value it; and empirical studies show that an active engagement predicts a range of positive outcomes for children (Sarkadi, Kristiansson, Oberklaid, & Bremberg, 2008).

Cultural and societal circumstances shape the way men enact their fatherhood, in particular their roles in the family and child education, as well as their beliefs about their own parenting abilities (Lamb, 2010). This diversity should be considered when studying or promoting parenting programs. It also seems important to increase fathers’ knowledge of child development and their role in it, helping them to interpret their child’s behavior and improving their confidence as a parent. This is especially relevant considering that economic realities require more demands from the parents, keeping them more time away from home, and leading to a decrease on their available time to be with their children (LaRossa, 2012). As our results show, less time working seems to help fathers getting more involved in their child routines/activities, yet when that isn’t possible, having a more responsive parenting style could result in a more involved approach.

References

Aboim, S. (2010). Gender cultures and the division of labor in contemporary Europe: A cross-national perspective. The Sociological Review, 58, 171-196. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2010.01899.x [ Links ]

Arsénio, C., & Santos, S. (2013). Paternidade na infância: Envolvimento paterno e estilos parentais educativos em pais de crianças em idade escolar. In A. Pereira et al. (Eds.), VIII Simpósio Nacional de Investigação em Psicologia (pp. 638-648). Lisboa, Portugal: Associação Portuguesa de Psicologia. [ Links ]

Bailey, W. T. (1994). A longitudinal study of father’s involvement with young children: Infancy to age 5 years old. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 155, 331-339. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1994.9914783

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph, 4, 1-103. doi: 10.1037/h0030372 [ Links ]

Bianchi, S., & Milkie, M. (2010). Work and family research in the first decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 705-725. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00726.x [ Links ]

Brown, G. L., McBride, B. A., Shin, N., & Bost, K. K. (2007). Parenting predictors of father-child attachment security: Interactive effects of father involvement and fathering quality. Fathering, 5, 197-219. [ Links ]

Cabrera, N. J., Fitzgerald, H. E., Bradley, R. H., & Roggman, L. (2007). Modeling the dynamics of paternal influences on children over the life course. Applied Development Science, 11, 185-189. doi: 10.1080/10888690701762027 [ Links ]

Cabrera, N. J., Ryan, R., Shannon, J. D., Brooks-Gunn, J., Vogel, C., Raikes, H., & Tamis-LeMonda, C. S. (2004). Fathers in the early head start national research and evaluation study: How are they involved with their children?. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice About Men as Fathers, 2, 5-30. [ Links ]

Cabrera, N., Shannon, J., Mitchell, S., & West, J. (2009). Mexican American mothers, fathers’ prenatal attitudes, and father prenatal involvement: Links to mother-infant interaction and father engagement. Journal of Sex Roles, 60, 510-526. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9576-2

Cabrera, N., Tamis-LeMonda, C., Bradley, R., Hofferth, S., & Lamb, M. (2000). Fatherhood in the twenty-first century. Child Development, 71, 127-136. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00126 [ Links ]

Coley, R. L., & Lansdale, P. L. (1999). Stability and change in paternal involvement among urban African American fathers. Journal of Family Psychology, 13, 416-435. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.13.3.416 [ Links ]

Coplan, R. J., Hastings, P. D., Lagacé-Séguin, D. G., & Moulton, C. E (2002). Authoritative and authoritarian mothers’ parental goals, attributions and emotions across different childrearing contexts. Parenting: Science and Practice, 2, 1-26. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0201_1

Coyl-Shepherd, D. D., & Newland, L. A. (2013). Mothers’ and fathers’ couple and family contextual influences, parent involvement, and school-age child attachment. Early Child Development and Care, 183, 553-569. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2012.711599

Coyl-Shepherd, D. D., Newland, L. A., & Freeman, H. (2010). Predicting preschoolers’ attachment security from parenting behaviours, parents’ attachment relationships and their use of social support. Early Child Development and Care, 180, 499-512. doi: 10.1080/03004430802090463

Craig, L. (2006). Does father care mean father share? A comparison of how mothers and fathers in impact families spend time with children. Gender & Society, 20, 259-281. doi: 10.1177/0891243205285212 [ Links ]

Culp, R. E., Schadle, S., Robinson, L., & Culp, A. M. (2000). Relationships among paternal involvement and young children’s perceived self-competence and behavioral problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 9, 27-38.

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as a context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 487-496. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487 [ Links ]

Deutsch, F. M. (2001). Equally shared parenting. American Psychological Society, 10, 25-28. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00107 [ Links ]

Escobedo, A., & Wall, K. (2015). Leave policies in Southern Europe: continuities and changes. Community, Work & Family, 18, 218-235. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2015.1024822 [ Links ]

Fabes, R. A., Leonard, S. A., Kupanoff, K., & Martin, C. L. (2001). Parental coping with children’s negative emotions: Relations with children’s emotional and social responding. Child Development, 72, 907-920. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00323

Ferguson, C. J. (2013). Spanking, corporal punishment and negative long-term outcomes: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 196-208. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.11.002 [ Links ]

Fernandes, M., Monteiro, L., & Veríssimo, M. (2015). Effects of educational level and working hours on father’s parenting style and level of involvement. Paper presented at the 17th European Conference on Developmental Psychology, Braga, Portugal.

Finley, G. E., & Schwartz, S. J. (2006). Parsons and Bales revisited: Young adult children’s characterization of the fathering role. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 7, 42-55. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.7.1.42

Fuertes, M., Faria, A., Beeghly, M., & Lopes-dos-Santos, P. (2016). The effects of parental sensitivity and involvement in caregiving on mother-infant and father-infant attachment in a Portuguese sample. Journal of Family Psychology, 30, 147-156. doi: 10.1037/fam0000139 [ Links ]

Fuertes, M., Faria, A., Soares, H., Oliveira-Costa, A., Corval, R., & Figueiredo, S. (2009). Dois parceiros, uma só dança: Contributos do estudo da interacção mãe-filho para a intervenção precoce. In G. Portugal (Ed.), Ideias, projectos e inovação no mundo das infâncias – O percurso e a presença de Joaquim Bairrão (pp. 127-140). Aveiro: Universidade de Aveiro.

Gaertner, B. M., Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., & Greving, K. A. (2007). Parental childrearing attitudes as correlates of father involvement during infancy. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 962-976. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00424.x [ Links ]

Garfinkel, I., McLanahan, S. S., & Hanson, T. L. (1998). A patchwork portrait of nonresident fathers. In I. Garfinkel, S. S. McLanahan, D. R. Meyer, & J. A. Seltzer (Eds.), Fathers under fire: The revolution in child support enforcement (pp. 31-60). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [ Links ]

Gauthier, A. H., & DeGusti, B. (2012). The time allocation to children by parents in Europe. International Sociology, 27, 827-845. doi: 10.1177/0268580912443576 [ Links ]

Harris, K. M., & Morgan, S. P. (1991). Fathers, sons, and daughters: Differential paternal involvement in parenting. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 531-544. [ Links ]

Hawkins, A. J., & Palkovitz, R. (1999). Beyond ticks and clicks: The need for more diverse and broader conceptualizations and measures of father involvement. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 8, 11-32. doi: 10.3149/jms.0801.11

Hofferth, S., & Anderson, K. (2003). Are all dads equal? Biology versus marriage as a basis for parental investment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 213-232. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-737.2003.00213.x [ Links ]

Hwang, C. P., & Lamb, M. E. (1997). Father involvement in Sweden: A longitudinal study of its stability and correlates. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 21, 621-632. [ Links ]

Ishii-Kuntz, M., Makino, K., Kato, K., & Tsuchiya, M. (2004). Japanese fathers of preschoolers and their involvement in child care. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 779-791. [ Links ]

Jacobs, J. N., & Kelley, M. L. (2006). Predictors of paternal involvement in childcare with dual-earner families with young children. Fathering, 4, 23-47. [ Links ]

Johnson, S., Li, J., Kendall, G., Strazdins, L., & Jacoby, P. (2013). Mothers’ and fathers’ work hours, child gender, and behavior in middle childhood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75, 56-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01030.x

Lagacé-Séguin, D. G., & Coplan, R. J. (2005). Maternal emotional styles and child social adjustment: Assessment, correlates, outcomes and goodness of fit in early childhood. Social Development, 14, 613-636. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00320 [ Links ]

Lamb, M. E. (2010). The role of the father in child development (5th ed.). New York, NY: Wiley. [ Links ]

Lamb, M., & Lewis, C. (2010). The development and significance of father-child relationships in two-parent families. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (5th ed., pp. 94-153). New York, NY: Wiley. [ Links ]

Lamborn, S. D., Mounts, N. S., Steinberg, L., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development, 62, 1049-1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01588.x [ Links ]

LaRossa, R. (2012). The historical study of fatherhood: Theoretical and methodological considerations. In M. Oechsle, U. Muller, & S. Hess (Eds.), Fatherhood in late modernity: Cultural images, social practices, structural frames (pp. 37-60). Leverkusen Opladen, Germany: Barbara Budrich. [ Links ]

Laursen, B., & Collins, W. A. (2009). Family relationships and parenting influences. In R. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of Adolescent Psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 331-362). New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Lewis, C., & Lamb, M. (2003). Fathers’ influence on children’s development: The evidence from two-parent families. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 18, 211-228. doi: 10.1007/BF03173485

Lima, J. (2005). O envolvimento paterno nos processos de socialização da criança. In J. B. Ruivo (Ed.), Desenvolvimento: Contextos familiares e educativos (pp. 200-233). Porto, Portugal: Livpsic. [ Links ]

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In P. H. Mussen & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (4th ed.). New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Marks, J., Bun, L. C., & McHale, S. M. (2009). Family patterns of gender role attitudes. Sex Roles, 61, 221-234. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9619-3 [ Links ]

McBride, B. A., & Mills, G. (1993). A comparison of mother and father involvement with their preschool age children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 8, 457-477. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(05)80080-8 [ Links ]

McKinney, C., & Renk, K. (2008). Differential parenting between mothers and father: Implications for late adolescents. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 806-827. doi: 10.1177/0192513X07311222 [ Links ]

Milkie, M. A., Kendig, S. M., Nomaguchi, K. M., & Denny, K. E. (2010). Time with children, children’s well-being, and work-family balance among employed parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 1329-1343.

Monteiro, L., Fernandes, M., Veríssimo, M., Pessoa e Costa, I., Torres, N., & Vaughn, B. E. (2010). Perspetiva do pai acerca do seu envolvimento em famílias nucleares. Associações com o que é desejado pela mãe e com as características da criança. Revista Interamericana de Psicologia, 4, 120-130. [ Links ]

Monteiro, L., Veríssimo, M., Castro, R., & Oliveira, C. (2006). Partilha da responsabilidade parental. Realidade ou expectativa?. Psychologica, 42, 213-229. [ Links ]

Monteiro, L., Veríssimo, M., & Pessoa e Costa, I. (2008). Escala de Envolvimento Parental: Actividades de cuidados e de socialização [Parental Involvement Questionnaire: Child care and sociaization related tasks]. (Unpublished manual). Lisboa: ISPA – Instituto Universitário.

Monteiro, L., Veríssimo, M., Pessoa e Costa, I., & Pimenta, M. (2008). Análise do envolvimento parental em famílias portuguesas com crianças em idade pré-escolar. [ Links ] Paper presented at the XIII Conferencia Internacional Avaliação Psicológica: Formas e contextos, Braga, Portugal.

Monteiro, L., Veríssimo, M., Vaughn, B. E., Santos, A. J., Torres, N., & Fernandes, M. (2010). The organization of children’s secure base behaviour in two-parent Portuguese families and father’s participation in child-related activities. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 7, 545-560. doi: 10.1080/17405620902823855

NICHD – Early Child Care Research Network. (2000). Factors associated with fathers’ caregiving activities and sensitivity with young children. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 200-219. doi: 10.1037/D893-3200.14.2.200

Oliva, A., Parra, A., Sánchez-Queija, I., & López, F. (2007). Estilos educativos materno y paterno: Evaluación y relación con el ajuste adolescente. Anales de Psicología, 23, 49-56. doi: 10.6018/23201 [ Links ]

Palkovitz, R. (2002). Involved fathering and child development: Advancing our understanding of good fathering. In C. S. Tamis-LeMonda & N. Cabrera (Eds.), Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 119-140). Mahwah, NJ: Routledge Academic. [ Links ]

Parke, R. D. (1996). Fatherhood. In J. Bruner, M. Cole, & A. Karmiloff-Smith (Eds.), The developing child. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Parke, R. D. (2002). Fathers and families. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Being and becoming a parent (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 27-73). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Parke, R. D. (2004). Development in family. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 365-399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141528 [ Links ]

Pederson, D. R., Gleason, K. E., Moran, G., & Bento, S. (1998). Maternal attachment representations, maternal sensitivity, and the infant-mother attachment relationship. Developmental Psychology, 34, 925-933. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.925 [ Links ]

Pedro, M. F., Carapito, E., & Ribeiro, T. (2015). Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire – Versão portuguesa de Autorrelato. Psicologia Reflexão e Crítica, 28, 302-312. doi: 10.1590/1678-7153.201528210

Perista, H., Cardoso, A., Brázia, A., Abrantes, M., Perista, P., & Quintal, E. (2016). Os usos do tempo de homens e de mulheres em Portugal. Lisboa: CITE – Comissão para a Igualdade no Trabalho e no Emprego.

Pleck, J. (2010). Paternal involvement: Revised conceptualization and theoretical linkages with child outcomes. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (5th ed., pp. 67-107). New York, NY: Wiley. [ Links ]

Pleck, J. H., & Masciadrelli, B. P. (2004). Paternal involvement by U.S. residential fathers: Levels, sources and consequences. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (pp. 222-306). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

Raley, S., Bianchi, S., & Wang, W. (2012). When do fathers care? Mothers’ economic contribution and fathers’ involvement in child care. American Journal of Sociology, 117, 1422-59. doi: 10.1086/663354

Robinson, C. C., Mandleco, B., Olsen, S. F., & Hart, C. H. (2001). The parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire. In B. F. Perlmutter, J. Touliatos, & G. W. Holden (Eds.), Handbook of family measurement techniques: Vol. 3. Instruments & index (pp. 319-321). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Russell, A., Aloa, V., Feder, T., Glover, A., Miller, H., & Palmer, G. (1998). Sex-based differences in parenting styles in a sample with preschool children. Australian Journal of Psychology, 50, 89-99. doi: 10.1080/00049539808257539 [ Links ]

Sarkadi, A., Kristiansson, R., Oberklaid, F., & Bremberg, S. (2008). Fathers’ involvement and children’s developmental outcomes: A systemic review of longitudnal studies. Acta Paediatric, 97, 153-158.

Shaw, B. A., Krause, N., Chatters, L. M., Connell, C. M., & Ingersoll-Dayton, B. (2004). Emotional support from parents early in life, aging, and health. Psychology and Aging, 19, 4-12. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.4 [ Links ]

Silva, A. T. B., Del Prette, A., & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2002). Relacionamento pais-filhos: Um programa de desenvolvimento interpessoal em grupo. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 3, 203-215. [ Links ]

Simons, L. G., & Conger, R. D. (2007). Linking mother-father differences in parenting to a typology of family parenting styles and adolescent outcomes. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 212-241. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06294593 [ Links ]

Steinberg, L. (2001). We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11, 1-19. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00001 [ Links ]

Torres, N., Veríssimo, M., Monteiro, L., Ribeiro, O., & Santos, A. J. (2014). Domains of father involvement, social competence and problem behavior in preschool children. Journal of Family Studies, 20, 188-203. doi: 10.1080/13229400.2014.11082006 [ Links ]

Torres, N., Veríssimo, M., Monteiro, L., & Santos, A. J. (2012). Father involvement and peer play competence in preschoolers: The moderating effect of the child’s difficult temperament. Family Science, 3, 174-188. doi: 10.1080/19424620.2012.783426

Torres, N., Veríssimo, M., Monteiro, L., Santos, A. J., & Pessoa e Costa, I. (2013). Father involvement and peer play competence in preschoolers: The moderating effect of the child’s difficult temperament. Family Science, 3, 174-188. doi: 10.1080/19424620.2012.783426

Tremblay, S., & Pierce, T. (2011). Perceptions of fatherhood: Longitudional reciprocal associations within the couple. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 43, 99-110. doi: 10.1037/a0022635 [ Links ]

Wall, K. (2007). Main patterns in attitudes to the articulation between work and family life: A cross-national analysis. In R. Crompton, S. Lewis, & C. Lyonette (Eds.), Women, men, work and family in Europe (pp. 86-115). London: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Wall, K. (2010). Os homens e a política de família. In K. Wall, S. Aboim, & V. Cunha (Eds.), A vida familiar no masculino – Negociando velhas e novas masculinidades (pp. 67-94). Lisboa: CITE – Comissão para a Igualdade no Trabalho e no Emprego.

Wall, K., & Leitão, M. (2015). Portugal country note. In P. Moss (Ed.), International Review of Leave Policies and Research 2014. Available at http://www.leavenetwork.org/lp_and_r_reports/ [ Links ]

Winsler, A., Madigan, A. L., & Aquilino, S. A. (2005). Correspondence between maternal and paternal parenting styles in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 20, 1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2005.01.007 [ Links ]

Yeung, W. J., Sandberg, J. F., Davis-Kean, P. E., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Children’s with fathers in intact families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 136-154. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00136.x

Zaslow, M., Weinfield, N. S., Gallagher, M., Hair, E., Ogawa, J., Egeland, B., . . . DeTemple, J. (2006). Longitudinal prediction of child outcomes from differing measures of parenting in a low-income sample. Developmental Psychology, 42, 27-37. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.27 [ Links ]

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Lígia Monteiro, ISCTE – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Av. Das Forças Armadas, 376, 1600-077 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: lmsmo@iscte-iul.pt

Submitted: 13/11/2016 Accepted: 20/04/2017

NOTES

* These authors gave equal contribution.