Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista Diacrítica

versão impressa ISSN 0807-8967

Diacrítica vol.27 no.1 Braga 2013

A beached whale posing in lingerie. Conflict talk, disagreement and impoliteness in online newspaper commentary

Isabel Ermida*

*Universidade do Minho, Centro de Estudos Humanísticos, Braga, Portugal.

ABSTRACT

This article investigates the correlation between the expression of disagreement and politeness concerns in the comment boards of the British Mail Online newspaper website. It focuses on a specific news report case – that of an overweight female model suing an advertising agency for using her image to promote body shame. The readers linguistic response to the legitimacy of her claims is closely entangled with their reaction to how her body looks on the photograph used in the ad campaign and reproduced in the article. Bearing in mind the diversity of posts, which range from encouraging remarks to insulting observations, the paper aims to discuss the expression of disagreement and, ultimately, the emergence of conflict talk in a specific case of Internet discourse (asynchronous online commentary), the central topic of which is womens body image. More specifically, it wishes to examine, from the perspective of Politeness Theory, how the various expressions of a specific face-threatening act – expressing disagreement – contributes to creating and reifying representations of femaleness and of physical perfection or desirability.

Keywords: Politeness; Disagreement; Conflict; Face; Female body; Internet discourse; Asynchronous online newspaper commentary.

*

Introduction

If compared with face-to-face conversation, the verbal interaction in online newspaper comment boards exhibits peculiar features. To begin with, its asynchronous nature challenges the turn-taking system and the adjacency sequences which Conversation Analysis has proven to characterise everyday dialogue (cf. Sacks et al. 1974), whereas its public and multiparty quality affects the formulation of opinions and the negotiation of agreement and disagreement. Brown and Levinsons Politeness Theory (1987) has successfully approached these issues, as well as those of face redress and conflict avoidance in interpersonal contacts. However, the anonymous character of the conversational exchanges online (vd. Donath 1999), together with the impersonal nature of the long-distance electronic contact, encourage a type of linguistic behaviour based on impolite and aggressive elements which tend to be dispreferred in face-to-face dialogues. Besides, when the topics are related not only to subjective and aesthetic preferences but also to ethical and moral issues, the conflictual potential increases and the confrontation assumes more serious and grievous forms.

The present article aims at analysing a specific case of Internet talk, at a time when the cybernetic space seems to win over face-to-face contact. It focuses on the comment pages of the British Mail Online newspaper website, where readers freely express their opinions about the topics covered. The article in question, published in Nov. 2011, reports on the case of a morbidly obese female model who is suing an advertising agency for allegedly misusing her image to promote body shame. The problematic ad campaign shows her in a sensuous photograph, reclining suggestively in a sexy outfit which reveals her more than abundant curves, with the following slogan: Did your wife SCARE you last night? The focus of this paper is the newspaper readers linguistic response to the legitimacy of her claims, given that her parallel pornographic activities may suggest a publicity stunt. This response is closely entangled with their reaction to how her body looks on the photograph used in the ad campaign and reproduced in the article. Bearing in mind the complexity of posts, which range from encouraging remarks to insulting observations, the paper aims to discuss the linguistic forms and the discursive strategies of disagreement through which a specific case of asynchronous online commentary constructs female identity in general and womens body image in particular.

The article starts by briefly discussing the state-of-the-art regarding linguistic approaches to online communication. Secondly, it offers a synopsis of the methodological framework of Politeness Theory, especially as far as face management, conflict and disagreement are concerned. Then, the textual analysis section examines the online dialogues according to a threefold division: backgrounded (or implicit) disagreement, hedged disagreement and foregrounded (or explicit) disagreement. The exercise aims at debating the management of the speech act of disagreeing in terms of the face of speakers and hearers as well as of the construction of the female body in Internet discourse.

1. Overview of online conversation criticism

Computer-mediated communication has been the object of numerous academic studies, especially since its generalisation towards the end of the 1990s. Many such studies are based on the classic premises of Conversation Analysis (CA, Sacks et al. 1974, Atkinson & Heritage 1984, van Dijk 1985), which concentrate on face-to-face contexts of linguistic interaction. Unlike these, online conversations are, owing to their asynchronous character, temporally and spatially divided. Besides, the management of the interactive space, which CA analyses in terms of turn taking, overlap, interruption, and so on, cannot apply to the delayed context of cybernetic communication. Similarly, questions such as register informality, with regard to the oral vs. written dichotomy, as well as the problems of temporariness, anonymity and multimodality, have also deserved critical attention, proving that computer-mediated dialogues assume a very specific nature, one that differs from regular conversations.

Before the emergence and generalisation of debate forums, it was mainly the email that absorbed the analysts attention as far as online communication goes. Studies by Yates (1996), Baron (1998) and Crystal (2001) tried to integrate this interactive genre into existing communication models. Thus, they regarded it in one of two ways: a) as a message written in the traditional format but transmitted through a new electronic medium (including job applications, online hotel bookings, family letters); or b) as a form of oral speech which happens to be written for transmission purposes. Other contributions (Ferrara et al. 1991, Maynor 1994, Collot e Belmore 1996) have identified a mixture of different influences and styles in email exchanges – a sort of an e-style, which is neither oral nor written, but a combination of the properties of both registers.

Baron (2003) also seeks to establish a comparison between email language and face-to-face conversations. The similarities she finds include informality (use of contracted forms, preferred coordinate clause constructions), succinctness (short messages intended for short answers) and the presupposition of temporariness which underlies communication. Among the differences stand out, in the three parameters, more radical informal usages in email than in face-to-face exchanges (such as colloquial forms of treatment, frequent omission of greetings, use of direct speech acts), a greater variability of the response time (which is due to the asynchronous nature of email and, even if extended, is acceptable, unlike face-to-face exchanges which demand instant response), and the fact that email can be printed, edited and stored, unlike oral exchanges which, unless recorded, are purely ephemeral.

With the appearance of plural and simultaneous participation sites – such as chat-rooms, forums, newsgroups – the discursive nature of cybernetic communication acquires fresh nuances and captures new criticism. Marcoccia (2004), for instance, examines the structure of the so-called online polylogues, whose public and asynchronous character makes them differ from interpersonal conversations. Firstly, the message exchanges in virtual forums are often truncated and the conversational sequences tend to be short. Unlike what happens at live interactions, the participants online speech often appears on an incorrect position of the sequential structure of the conversation. The participation pattern also differs from face-to-face exchanges, insofar as the author (the actual producer of the message) can hide behind the speaker (the persona holding the nickname that appears on the screen).

Other studies aim at understanding how plural online interaction allows participants to use – and to develop – communicative and pragmatic competencies. Lewis (2005), for instance, analyses French and British forums of political discussion (a case of what he calls many-to-many interaction) and he reveals a tendency for the fragmentation of communication, which changes from a multi-party interaction to a number of overlapping dialogues (each taking place between two speakers). On a different note, Clarke (2009) focuses on the discursive construction of interpersonal relationships among trainee teachers, by using a Critical Discourse Analysis framework to understand the legitimisation strategies used. Montero-Fleta et al (2009) examine the degrees of formality in two types of chat-rooms (one, Catalan, discussing football; the other, British, discussing the Palestinian crisis), whereas Savas (2011) attempts to understand the variation in the stylistic options of non-presential synchronic forums in terms of individual and contextual differences.

The occurrence of (im)politeness in computer-mediated communication – which the present article aims at discussing – has also been studied. Donath (1999) discusses the extent to which construction of face is important for the members of online communities, whose profiles seem to be carefully managed and which correspond, not to what those members are, but to what they wish to convey. Other scholars have ventured that projecting an image of sophistication, education and courtesy has stopped being of interest to cybernauts. Baron (2003) precisely discusses the decline in public face in contemporary American society and the reflection the phenomenon has had in computer-mediated communication. The decrease in social class differences, the increase in inter-class mobility, the disconnection between schooling and economic success and the strong emphasis on youth culture have caused less impetus to learn the fine points of etiquette or dress up for job interviews and less public interest in developing the sophisticated thought and language that higher education traditionally nurtures (idem, ibid.: 90).

Upadhyay (2010) also investigates the language of the Internet, in particular computer-mediated reader responses (the same focus as the present article), with regard to the study of impoliteness, as well as identity. He posits that respondents may use linguistic impoliteness in three ways: a) strategically to communicate disagreements, b) to argue against an out-groups ideological views, or c) to discredit ideological opponents. Upadhyay also defends that the employment of impoliteness is linked to the respondents identification with, or rejection of, a groups ideological position and goals. Eisenchlas (2011) finds other reasons to explain the occurrence of impoliteness in online talk. He claims that the democratic nature of the Internet, the anonymity of its participants and the discontinuous character of the interaction turn the notions of hierarchy and deference, as well the corresponding questions of face, into more negligible concerns than those existing in face-to-face communication.

In a comprehensive, groundbreaking book, entitled Cyberpragmatics: Internet-Mediated Communication in Context (2011), Francisco Yus also relates the language of Internet – which he analyses in its various manifestations and corresponding genres, from email and chatrooms to blogs and personal webpages – with politeness issues. A curious fact which Yus (2011: 257) points out is that the online use of politeness strategies can be chosen by the user or they can be imposed by a moderator of the system used. Besides, Yus (2011: 270) claims that the Internet is particularly appropriate for an analysis of the trans-cultural differences in the use of politeness. After all, users from all over the world employ this electronic medium to communicate, both asynchronously (as in email) and synchronously (as in chatrooms). The specific nature of online talk influences the use, or misuse, of politeness. As Yus (2011: 263) puts it, the lack of physical co-presence and the reduced nonverbal contextual support influence the choice of a particular politeness strategy. But if the Internet lacks resources otherwise available to speakers in everyday communication, it provides alternative conversational crutches that are non-existent in other written media, such as letters or the press. As Yus notes (2011: 168), an emoticon can soften the propositional content of an utterance or disguise its illocutionary force, much along the lines of what politeness does.

Having set the genre of texts on which we will focus, it is necessary to briefly discuss the theoretical tools to use in the analysis. Next, we shall review the concept of face, a central one to politeness theory, as well as to studies of disagreement and identity.

2. Face management

The vast and ever-growing scholarship on politeness attests the undeniable vitality of the topic. Notwithstanding the diversity of the approaches, most of the existing research reaffirms the impact of Brown and Levinsons pioneering work. Actually, the core concepts of the Theory of Politeness (1987) continue to inspire a steady flow of academic studies.

Brown and Levinsons Theory of Politenessrests upon the notion of face, which echoes the common expression losing face (and, by extension, getting embarrassed or humiliated – 1987:61). The concept if borrowed from Goffman (1967: 306), who defines it as an image of self delineated in terms of approved social attributes and, consequently, as the positive social value a person effectively claims for himself. Hence the parallel notion of face work, which covers all the actions an individual undertakes so as to act in accordance with the demands of face. These actions serve to counterbalance any incidents which may threaten face and to protect the speaker from his or other speakers embarrassment. The culturally determined repertoire of face protection strategies is dual: defensive (protecting our own face) and protective (protecting other peoples face) (Goffman 1967:310).

The theoretical implications of Goffmans fertile concept are numerous, complex, and sometimes polemical, as is the case of its purported universality (see, e.g. Mao 1994 and Earley 1997). Goffman (1967:319) does concede that underneath their differences, people everywhere are the same, and he claims that every society encourages its members to be perceptive, to have feelings attached to self and a self expressed through face. Much Anglo-American bibliography on politeness, as Bargiela-Chiapinni (2003:1462) points out, tries to redefine the relative weight of the concept of face in the West as opposed to its manifestations in other cultures. In Japan, empathy, reciprocity and dependence are overriding principles (cf. Hill et al. 1986, Ide 1989), whereas in China face acquires quite different nuances (Lim 1994).

Brown and Levinson defend the universality of face in the very title of the 1987 book (Politeness: Some Universals of Language Usage), as well as in explicit passages in the body of the text: we are assuming that the mutual knowledge of members public self-image or face, and the social necessity to orient oneself to it in interaction, are universal (1987:62). Although they admit that the core concept is subject to cultural specifications of many sorts (1987:13), Brown and Levinson establish the concept of Model Person, which is allegedly a reasonable approximation to universal assumptions (1987:84). Face, or the public self-image which the Model Person wishes to project, is twofold: positive and negative. Positive face is the wish that our image be appreciated and accepted by others, whereas negative face is the wish that our space be protected from intrusion and imposition. The former bears on the construction of identity and consensus, and on our attempt to be ratified, understood, approved of, liked or admired, whereas the latter has to do with territorial integrity and our attempts not to be disturbed.

In social interaction, some situations of verbal and non-verbal communication intrinsically threaten face or, in Brown and Levinsons words (1987:65), run contrary to the face wants of the addressee and/or of the speaker. These situations consist in the so-called face-threatening acts, which jeopardize, on the one hand, either the speakers or the hearers face, and on the other hand, either their positive or negative face. For instance, when a speaker apologises, s/he is admitting to incorrect behaviour, thus threatening his/her positive face, but if the speaker thanks the hearer, the former jeopardizes his/her negative face, by incurring in a debt and allowing the hearer to ask for a make-up favour later on. On the hearers end, a criticism by the speaker is obviously a threat to positive face, since it indicates that the speaker does not approve of the hearers behaviour, whereas a request threatens the hearers negative face, since it invades the hearers territory by asking him/her to do something. In face of such threats, speakers my simply refrain from doing the face-threatening act altogether.

However, if speakers cannot avoid doing it or if they deem it preferable to run the risk, they may use certain strategies to minimize such a risk and protect the mutual vulnerability of face. In this case, they have two possibilities to choose from (cf. Brown and Levinson 1987:69): 1) to do the face-threatening act off record, that is, in an indirect way, by providing the hearer with hints such as metaphor, irony, and understatement; and 2) to do it on record, that is, explicitly and ostensively, in one of the following ways:

Doing the act without redressive action, baldly, that is, in a direct and clear way, without any mitigating forms (for instance, and order would be performed by means of a straight imperative form)

Doing the face-threatening act with redressive action, that is, by employing mitigating action, be it positive politeness (for instance, by using in-group identity markers, avoiding disagreement, exaggerating interest, telling jokes, etc.) or negative politeness (for example, apologising, being indirect, not coercing, impersonalizing, etc.)

This article will discuss how a major strategy of positive politeness – seeking agreement – gets to be manipulated in the comment pages of the Daily Mail online. But before doing so, a few preliminary observations regarding the issues of conflict and disagreement are in order.

3. Politeness, conflict and disagreement

At the outset of heir book (1987:1), Brown and Levinsons state: ( ) politeness, like formal diplomatic protocol ( ), presupposes [a] potential for aggression as it seeks to disarm it. And they add that politeness makes possible communication between potentially aggressive parties (ibid.). The role of polite behaviour in taming down aggressive urges is a key factor to successful social interaction. Identifying possible symptoms of conflict requires a constant vigilance and the knowledge of what Brown and Levinson call a precise semiotics of peaceful vs. aggressive intentions (ibid.)As such, politeness constitutes an important form of social control (1987: 2).

This conception of politeness as an antidote to conflict and aggression is also present in Leech (1983), whose Principle of Politeness also aims at preventing or solving any incompatibility between speakers. In Leechs words (1983:82), the regulatory role of this principle is to keep the social equilibrium and the friendly relations which enable us to assume that our interlocutors are being cooperative in the first place. Leechs Principle of Politeness is divided into six maxims, namely Tact, Generosity, Approbation, Modesty, Agreement and Sympathy. The Agreement maxim, in particular, reads: a) Minimize disagreement between self and other, and b) Maximize agreement between self and other. Minimizing disagreement is listed first because, as Leech ventures, avoidance of discord is a more weighty consideration than seeking concord (1983: 133). Leech also holds that there is a tendency to exaggerate agreement with other people, and to mitigate disagreement by expressing regret, partial agreement, etc. (1983: 138). Other ways speakers employ to avoid disagreement is the use of indirect speech acts, by means of such strategies as modalization and passivization. In short, the more indirect the speaker, the more polite and the more capable of avoiding conflict.

In Brown and Levinsons model, the idea of conflict management is closely related to the notion of power, one of the three sociological factors which are crucial to determining the level of politeness which a speaker will use to an addressee (1987:15), namely: Power, Distance and Ranking of the Imposition. The more powerful the speaker is, the less room there will be for conflict to arise. Indeed, in many situations of social interaction the role of the relative power of participants is crucial, especially if the interlocutor is eloquent and influential, or is a prince, a witch, a thug, or a priest (1987:76), in which case he may well impose his own plans and his own self-evaluation (ibid.). And, of course, by imposing our own opinion and evaluation we threaten the positive, as well as the negative, face of the hearers, in that we show we do not respect or appreciate their opinion, and intrude upon their territory by requiring them to accept ours. One thing is to seek agreement; another is to impose it.

The issue of agreement vs. disagreement is actually well established in Brown and Levinsons model. Seeking agreement and avoiding disagreement are complementary strategies that aim at ascertaining common ground between the speaker and the hearer, thus indicating that S and H both belong to some set of persons who share specific wants, including goals and values (1987: 103, see also 112-3). So important is the desire to agree, or to appear to agree, with the hearer that speakers may resort to token agreement. In an earlier study by Sacks (1973) a Rule of Agreement explains the remarkable degree to which speakers may go in twisting their utterances so as to appear to agree or to hide disagreement (Brown and Levinson, 1987: 114). This is the case of responding to a preceding utterance with Yes, but , rather than a blunt No. We will see occurrences of token agreement, or what I call disagreeing by agreeing in the present corpus.

In 2004, Miriam A. Locher wrote an important contribution to the study of disagreement from the point of view of Politeness Theory. In Power and Politeness in Action: Expressing Disagreement in Oral Communication, she writes: Conflict can be argued to link the exercise of power, politeness and disagreement on a general level (2004: 94). Along the lines of Waldron and Applegate (1994:4), who define verbal disagreements as a form of conflict insofar as they are characterized by incompatible goals, negotiation, and the need to coordinate self and other actions, Locher claims that disagreeing speakers are in conflict not only in terms of content but also in terms of protecting the hearers face, as well as their own. Getting their point across without sounding presumptuous or injuring the hearers image causes friction and potentially leads to conflict, which is where politeness comes in. Locher (2004) establishes eight categories for expressing disagreement, with different degrees of politeness: the use of hedges, giving personal or emotional reasons for disagreeing, the use of modal auxiliaries, shifting responsibility, stating objections in the form of question, the use of but, repeating an utterance by a next or the same speaker, and non-mitigated disagreement. We will see how some of these categories occur in the corpus under focus.

Previous studies on disagreement have shed light on other interesting facets of the phenomenon. To begin with, disagreements need not be negatively charged, or psychologically detrimental. Schiffrin (1984: 329) elaborates on sociable arguments and claims that expressing disagreement may be part of the expected speech situation and thus be a source of enjoyment. In a later study (1990: 241), she mentions that although arguments may at first sight look like the epitome of conflict talk, they may in fact be regarded as a cooperative or competitive way of speaking. Other authors also view disagreement – or its strongest version, argument – as a reaction that is not necessarily a dispreferred or negative one. Charles and Marjorie Goodwin (1990: 85), for instance, claim that despite the way in which argument is frequently treated as disruptive behaviour, it is in fact accomplished through a process of very intricate coordination between the parties who are opposing each other. And Kotthoff (1993: 193) defends that once a dissent-turn-sequence has been displayed, opponents are expected to defend their positions, showing fewer reluctance markers, which makes disagreement become a preferred response.

Yet, disagreeing does carry a risk of confrontation and hence of negative psychological tension. Kakavá (1993: 36) explains the vulnerability of the disagreeing speaker, who may face criticism and be the object of counter-attack:

Since disagreement can lead to a form of confrontation that may develop into an argument or dispute, disagreement can be seen as a potential generator of conflict. Not only can disagreement create conflict, but it can also constitute conflict since an argument is composed of a series of disputable opinions or disagreements.

Perhaps because of this conflict potential, disagreement tends to be regarded as a dispreferred answer. Pomerantz (1984) distinguishes between weak and strong disagreements and claims that the former, as dispreferred answers, resort to such delaying strategies as hesitations, requests for clarification, no talk, turn prefaces, partial repeats and other repair initiators (1984: 70). Strong disagreements, on the other hand, do not make use of any of these devices.

In Learning Politeness: Disagreement in a Second Language (2009), Ian Walkinshaw offers a useful taxonomy of disagreement, which includes four categories. By way of example, the fictional situation is that of a speaker responding to a question of whether he likes a second-hand couch:

a. Explicit / direct disagreement: I dont like this couch at all. Having only one literal meaning, this FTA will only be performed if the speaker is not concerned with retaliation from the hearer (Walkinshaw 2009: 73)

b. Disagreement hedged with positive politeness: Its a nice couch, but I dont like it. In this case, disagreement is softened by expressing appreciation of the hearers likes, wants and preferences.

c. Disagreement hedged with negative politeness: Youve obviously set your heart on it, but I dont like it. This includes the mitigating strategies oriented towards the hearers desire to act freely as s/he chooses.

d. Implied disagreement: Um, well, its certainly an interesting colour... This roughly corresponds to Brown and Levinsons off-record strategies, such as hinting and vague, unfinished sentences, which free the speaker of just one communicative intention, and thus of the responsibility for the FTA.

This taxonomy is to some extent reminiscent of Scotts (2002) distinction between two primary types of linguistic disagreement: backgrounded versus foregrounded disagreement, which exist on a continuum of increasing explicitness and escalating hostility (2002: 301). (We will see in the textual analysis section how this continuum operates in the present corpus.) Scott also divides the latter into two patterns of disagreement in terms of targets, namely collegial disagreement versus personal disagreement (which includes ad hominem attacks).

In Impolineness: Using Language to Cause Offence (2011), Culpeper establishes a further parallel between Politeness Studies and what he correctly labels Conflict Studies. Two subfields of research into conflict are directly related to impoliteness. First, interpersonal conflict bears on the existence of difference or incompatibility between people and on the interaction between parties that have opposing viewpoints, interests or goals. Secondly, conflict in discourse involves any type or verbal or non-verbal opposition taking place in social interaction, ranging from disagreement to disputes. Both subfields are subsidiary to impoliteness in the following way:

If impoliteness involves using behaviours which attack or are perceived to attack positive identity values that people claim for themselves or norms about how people think people should be treated, then it involves incompatibility, expressing opposing interests, reviews, or opinions, verbal or non-verbal opposition – it is intimately connected with conflict. (Culpeper, 2011: 5)

A final bibliographical cornerstone that requires mention is a very recent special issue of the Journal of Pragmatics (Sep. 2012), devoted to the study of Disagreement. In its Introduction, Angouri and Locher (2012) propose four key premises to theorising disagreement. The first is the everyday nature of the phenomenon. The second is that disagreement may be not only tolerated but expected, instead of being an exceptional speech act. The third is that disagreeing is not necessarily negative. And the fourth is that disagreeing will have an impact on relational issues (face-aggravating, face-maintaining, face-enhancing) (2012: 1549). Although some of the articles in the volume revolve around institutional settings and workplace scenarios (cf. Marra 2012, Angouri 2012), others crucially focus on online discourse. Langlotz and Locher (2012), for one, identify instances of the expression of emotional stance in news website postings through conceptual implication, explicit expression, and emotional description. And Bolander (2012) analyses the use of (dis)agreement in personal / diary blogs, arguing that even though the participation framework of blogs encourages explicitness, there is a greater need to signal responsiveness explicitly when readers address other readers than when readers address bloggers.

We will next see the forms which the participants in online conversations – the focus of the present study – use to express agreement and disagreement, and we will try to identify the different linguistic strategies used to express alignment and approval, on the one hand, and confrontation and rebuttal on the other. Perhaps the former bear on the feeling of a shared experience of events and situations (on the concept of networked community, see e.g. Castells 2000) and the latter on the influence of the factors of Distance, Anonymity and Third-Party opinion. The following sections seek to test these hypotheses.

4. Sample description

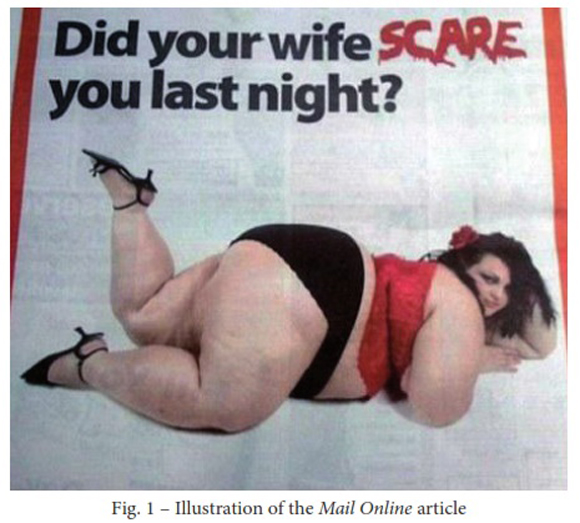

The corpus of texts under focus in the present article is a set of online written productions of a dialogical nature – or, along Marcoccias lines (2004), of a polylogical character, since they involve more than two participants, and many of the utterances respond to more than one speaker at a time. They were published on the days following the publication of an article on the Mail Online newspaper website, entitled Supersized model describes horror after discovering her scary image was used to promote dating site for men who want to cheat (Nov 9, 2011). The article crucially includes an illustration, shown next:

Together with the image is the following subtitle: Big is beautiful: Jacqueline, who unwittingly features in the ad, believes the marketing material suggests, blatantly, that fat people are patently undeserving of love and loyalty. These cues are not only obviously provocative but successfully so. The number of responses to the article is, not surprisingly, high and the intensity of the opinions expressed quite remarkable, in such a way that the discursive situation becomes a very interesting case study of argumentative discourse in general and multi-party argument in particular (Maynard 1986, Goodwin and Goodwin 1993: 100). At the same time, it lends itself to an analysis of the management of face and the violations of the politeness strategies usually at work in face-to-face interactions. On the whole, the corpus includes 369 posts, each of which containing one or more sentences, which amount to 18757 words.

5. Content discussion

The core of the article is that the morbidly obese model, Jacqueline, claims that a picture from a photo-shoot she unsuspectingly made was used, without her permission, to advertise an extra-marital affairs website and to promote body shame. The fact that the photo-shoot was patently suggestive in sexual terms, together with the circumstance that Jacqueline runs a pornographic website, are rather incriminating factors that do not help her case. The complex range of reactions to the article spans not only her physical appearance – from which spring judgements as to body perfection, desirability and health – but also the ethical issues involved in her side activities as a porno figure.

Therefore, the expression of disagreement covers a broad scope of topics, which are raised, debated, dropped and recovered along the argumentative sequence. More specifically, the various targets of disagreement in the corpus are the following:

a. Disagreeing about obesity being beautiful (The newspaper article subtitle uses the expression Fat is beautiful)

b. Disagreeing about obesity being ugly or deserving attack (Jacquelines court case rests upon the complaint of body shame caused by obesity)

c. Disagreeing about objectification of women (Many commentators view Jacqueline as a female scapegoat)

d. Disagreeing about adultery (The advertisement is for a dating agency for married men)

e. Disagreeing about hypocrisy (Jacqueline complains of her body being misused even though she exploits it herself for sexual purposes)

The complexity of the analysis also bears on the fact that the disagreement turns occur in a sequence that is not dyadic, but multiparty, admitting different strands of discursive input. Besides, the speech act of disagreeing is closely related to, and actually overlaps with, other speech acts, such as criticising, protesting, reprimanding, etc. Actually, from a speech-act theory perspective, the analysis of the linguistic sequences is particularly challenging, since the illocutionary force continuum ranges from warnings and overt condemnations to encouragements and expressions of support, whose boundaries are often blurred. At an interpersonal level, two sides build up from the beginning of the exchange: a support side and a rejection one, a divide which immediately feeds a potential for disagreement and conflict. From a Conversational Analysis perspective, the asynchronous nature of the exchanges makes the turn-taking system inoperative, as well as the occurrence of interruption or overlap. Yet, it is interesting to note that the turns do occur in response to previous ones. Actually, some posts constitute direct replies to others, whereas other posts exist independently, ignoring previous conversational input. It should also be noted that long turn-takes alternate with very short ones – sometimes, even one-word replies (as is the case of Oink!).

From the standpoint of the Theory of Politeness – which is the primary theoretical tool in hand – the texts exhibit a great degree of complexity. As an anonymous forum, the comment pages of the newspaper encourage the free expression of thought, which may explain why some posts are such ostensive infringements of the politeness principles, especially positive politeness. Also, the fact that the respondents are speaking about a third party – Jacqueline, who is not taking part in the polylogue – may partly be the reason for the expression of strong, confrontational opinions, which often subvert the interactional protocol presiding over daily face-to-face conversations. As Leech (1983: 133) claims, politeness towards an addressee is generally more important than politeness towards a third party.

We will divide the analysis into three parts, in accordance with the three major patterns of disagreement found in the texts.

5.1 Backgrounded disagreement: Implicitness and indirectness

Since disagreeing has the potential to damage another persons face, the speaker will normally avoid performing the FTA, or try to minimize its impact. Going off-record allows the speaker to remain in the realm of the implicit, where it is not possible to attribute only one clear communicative intention to the act (Brown and Levinson 1987: 211). Off-record strategies demand inferential efforts by inviting conversational implicatures, since they typically break Grices cooperative maxims (ibid: 213). Scott (2002: 74) calls off-record disagreeing backgrounded disagreement and confirms that it is a way to avoid responsibility for the FTA because it is left to the recipient to interpret it. The occurrences of backgrounded disagreement in the corpus under focus include many of the linguistic realizations which Brown and Levinson (1987: 69) postulate: metaphor and irony, rhetorical questions, understatement, tautologies, all kinds of hints as to what a speaker wants or means to communicate.

Let us begin with metaphor, a category of Quality violations, for metaphors are literally false (Brown and Levinson, 1987: 222). Expressions of disagreement in the Mail Online comment board as to the claim that fat is beautiful often assume metaphorical shapes. Referring to the obese model as a whale or a pig (which also covers metonymical extensions by way of their voices) is a recurrent element in the texts, be it in an openly insulting tone, as we will see later, or in a more indirect manner, as follows:

SAVE THE WHALES... Oh wait, on second thought...- Eoin Power, Osaka, Japan

Hold on, where did I put my harpoon? – Eric, Canada

Beware the Norwegian Whaling feet cometh – howardski, londonski

Languishing suggestively... or beached, to give this pose its proper nautical nomenclature. – Richard, Middlesbrough

Oink! – American, Philadelphia

oink – SaminTexas, Texas

Other metaphors cover objects instead of animals, like food disposable bins. The following comment is particularly interesting in locutionary terms because it displays a fictional dialogue between two interlocutors – the obese model and an interviewer. Although the passage is rather derisive, the speaker manages to remain off-record:

Shes a good advert for a food disposable bin... Whats your favorite hobby madam xxx... Why eating naturally. Whats your favorite nibble madam xxx... Why ice cream, more ice cream and ever more ice creammmmmm-mmmmmmmmmmm-mmm-mmmmmmmmmmmmm. – miss 60s, los angeles

The following occurrence of metaphor compares the model with food itself. It is a curious verbal production insofar as the commentator assumes Jacquelines voice, in a contemptuous role-play which humorously alludes to her lack of education by means of wrong verb conjugations and lack of grammatical concordance:

Im a rolly polly pudding and pie and i kisses the boys and squashed them with my enormous mellons and then i flattened them with my enormous backside – Tom, Chicago.

Another metaphor, mixed with metonymy (part for the whole), compares Jacqueline with a countrys province, by means of a reference to the postal code she would deserve if she were one:

If she lived in Britain, shed get her own postcode. – Adam Mann, UK

The use of rhetorical questions, another case of infringement of the Quality maxim, helps the speaker to soften the strength of the disagreement. Brown and Levinson (1987: 223) explain that to ask a question with no intention of obtaining an answer breaks the sincerity rule on questions. In the next passage, the commentator disagrees that an obese woman may be a legitimate target of adultery by counter-arguing that marriage also affects mens body negatively. The commentary exhibits a series of rhetorical questions, signaled with several question marks at a time, which leave their answers hanging in the air (ibid: 223) and save the speaker the responsibility for the propositional content of the utterance. The use of hedges, such as I presume, maybe, and just (a thought), also indicates that the speaker is going off-record:

Men saying that they would dump their wives if they got obese when they had been a size 12 at marriage – I presume still have their full heads of hair, lithe muscular bodies, full sets of healthy teeth and the sex drive they had when THEY got married??? Or are they balding, pot bellied, couch potatoes with bad breath and more hair coming out of ears and nose than on the whole of their head, who do more talking about sport and sex than doing it??? Maybe your wife is disappointed with your looks too but loves you anyway?? Just a thought. – Me again, Newbury, Berkshire

A very similar case takes the opposite argumentative stance, defending the males point of view. The disagreement, once again, resorts to rhetorical questions, mixed with hedges such as really, some and surely:

So, according to her, if a couple marries when she is like a size 6 and then balloons to a size 32 and then the husband cheats, because he is no longer attracted to his wife that the entire situation is HIS fault? Surely it is her fault as well?! – Malia, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA

The use of irony, by which the speaker says the opposite of what s/he means, also expresses implicit disagreement. The corpus exhibits several instances of ironical utterances. In the following passage, a commentator disagrees with the idea that being fat deserves derision, by using the adjectives interesting, glad and sane in a patently ironical way:

Interesting, the fat-bashing. But identity-theft is okay? Glad there are some sane people commenting. – Amber, London

A very good example of irony is the following utterance, where a female commentator shows her dislike for obesity and her implicit disagreement regarding the corresponding values:

Its official. Im never eating, ever again. – Tina, Derby

Likewise, the following dialogue sequence between two commentators – Shaun and Andy – reveals an ironical response on the part of the speaker who initiated the exchange. Shaun initially disagrees with the purported hate of which Jacqueline is a victim, and Andy replies with a play on words regarding the expression having too much on ones plate. Shauns closing remark shows that, contrary to what he says, he obviously did not like Andys enthusiasm for his joke. The use of the plural pronoun helps to signal his dual illocutionary intention:

Whats with the hate on her? Doesnt she have enough on her plate already? – Shaun, Liverpool, 09/11/2011 15:29 / From looking at the size of her Shaun, I dont think that theres ever much left on her plate..... – Andy, Frodsham, 09/11/2011 16:23 / We like your enthusiasm for our joke thank you Andy. – Shaun, Liverpool, 9/11/2011 16:53

Unlike irony, sarcasm does not mean the opposite of what is said (thus violating the quality maxim); instead, it means more than what is actually expressed (thus violating the quantity maxim), which is why it also goes by the name understatement. So as to express disagreement that Jacqueline is beautiful, the four following commentators resort to sarcastic understatement:

Note to self: initiate strenuous exercise program immediately. – K.M., Coeur dAlene, Idaho, USA

Is this the American version of TWIGGY ??? – Frank, Slough

Somehow I have a nervous feeling about a possible missing little pets location during the photoshoot. – Jon, NY

Supersize model. The oxymoron of the 21st century. – Cat Lover, London

I look forward to their next ad: Did your HUSBAND scare you last night? Bet that could create some publicity, too – with the right illustration of course. – Damascena, Town

The following is a very curious case which uses understatement to criticize understatement. In reply to an earlier comment by a woman (God forbid if a woman puts on a bit of weight! – Pam, Rutland), a male commentator replies:

Quite possibly the understatement of the year.........size 32 is now a bit of weight. – Adam, Glasgow

Two other commentators employ the adjective enormous sarcastically, and they establish a synecdoche between her problem, or her issue (something that is part of her), being as big as she is:

Well she is correct about there being an enormous problem. – Taylor, New York City USA

Use of the word enormous when describing her issue was an unfortunate word choice... – Lauren, London

Hinting is also a typical strategy of indirectness, and as far as disagreement goes, it also plays the function of backgrounding the illocutionary force of the utterance. Hints violate the Relation maxim in that they require the recipient to establish the relevance of the utterance to the issue in hand. The following line hints at the practical difficulties that an overweight female body can pose to a male lover. Though the impoliteness is not overt, it is obvious that no redress is offered, only the off-record statement of a (tabooed) fact:

You will never get in there. – Steven, Surrey

A particularly interesting comment happens when a reader responds to Jacqueline directly, by using the second-person pronoun. Unlike most other comments, he speaks to her, not about her. He begins by quoting her words in inverted commas, and goes on to use several off-record devices, such as rhetorical questions, ellipsis (in the form of suspension marks) and irony (saying she is a complicated woman whom no one understands):

I find the very idea that there exists a business based solely around the facilitation of infidelity appalling. Let me guess, you still accept paid memberships from married men? Thought so. Lovely lark this one, doesnt like her body being exploited.... unless its her own porn site. Doesnt like infidelity.....unless the infidelity is visiting her site. She is a complicated woman and no one understands her but her ice cream sandwiches. – Greg, Canada

Finally, another off-record strategy Brown and Levinson mention and which may be used to express implicit disagreement is the employment of generalizations. In the following comment, a speaker points out that although everybody nowadays criticizes smoking, criticizing obesity is still generally condemned:

Its socially acceptable to tell smokers now that smoking will kill them and that its awful and yucky. It wasnt always acceptable back in the day to speak aloud about it. When will it become acceptable to tell people you are overweight and killing yourself?! – Odell, Tampa, FL,

Likewise, the following comment is constructed on the basis of generalization. The use of discursive subjects like people or you (which plays the role of impersonal one) helps the speaker express her disagreement in a backgrounded way:

People know that if theyre overweight its very unhealthy. Broadcast and print media carry many stories and statistics about the health risks of obesity. Unless you are talking about heart-to-heart talks with people to whom you are close or doctors talking to patients, I hope its never socially acceptable to tell people theyre fat and going to die. Its rude, cruel, and pointless. Criticizing strangers because you believe they are overweight wont make them change their behavior. – Carol, U.S.A.

The same can be said of the following general statements, the first about the diversity of the human body in general, the second about the fat acceptance movement, which is another case of impersonalization (through nominalization):

Women (just like men) come in all sizes. Fat, thin and in-between. These ads are horribly degrading to women in general. I see her point. – rajapatee, orlando fl

The fat acceptance movement is literally killing people, and those behind it should be stopped. – Kate, Washington DC, USA

5.2 Disagreement hedged with positive and negative politeness:

The occurrence of comments that involve disagreement but attempt to soften its strength in a polite way cover several linguistic strategies, some of which are aimed at positive face, others at negative face. On the whole, the corpus exhibits several examples of the two cases. Positive politeness strategies are oriented toward the positive self-image that [the speaker] claims for himself (Brown and Levinson 1987: 70) and can be used to redress the face-threat inherent in disagreement. Walkinshaw (2009:73ff) also studies the use of positive politeness in disagreements, which he regards as an attempt to attenuate disagreement by expressing appreciation of the hearers likes, wants and preferences.

The two following examples are interesting cases of a speaker disagreeing that morbid obesity may be regarded as beautiful while protecting the face of moderately obese readers. Indeed, so as to shield the positive self-image which the latter naturally claim for themselves, the speakers preface their disagreement by introducing an apology (see Locher 2004: 134), in the first case, and a concession in the second (Big may be beautiful...), both of which are followed by but:

No offense to big women, but this is disgusting. – Amanda, Houston, TX

Big may be beautiful, but morbidly obese is disgusting, no apologies.

Claiming common ground by using in-group identity markers and first-person plural pronouns (we, us) is a positive politeness strategy which Brown and Levinson (1987: 107, 127) also stipulate: by using an inclusive we form, when S really means you or me, [the speaker] can call upon the cooperative assumptions and thereby redress FTAs. The following speaker tries to assuage her disagreement by using a solidarity strategy and pretending she is part of a group (see also Chilton 1990: 217). In other words, she disagrees with the views expressed by a group but pretends she is part of that group and that their self-image is hers too. The use of lets (contraction of let us), in particular, implies a mitigated order, with the exercitive illocutionary force (cf. Austin) disguised:

This is a human being we are talking about. Why do people put so much emphasis on whats on the outside? Shouldnt we be more tolerant and understanding? We dont know a persons circumstance as to why or how they became that way. Lets stop hurting each other and fix ourselves instead. – Victoria, Los Angeles, CA USA

Another curious example of the use of in-group identity markers, in particular address forms, comes in reply to a previous comment by a male participant (You cannot pile on a trazillion pounds then accuse your partner of being shallow if they no longer desire you. – Toni, Herts). The respondent resorts to a term of endearment (which may have some ironical undertones) so as to soften the strength of her disagreement, which is otherwise constructed on the basis of negation (note the recurrence of the adverb not):

Desire isnt love, sweetie! Love must fuel desire, not the other way around. ( ) The best sex is about love, not lust, and not just about what a person looks like. Theyre still the same person inside, no matter what the outside is like. – ShowMeTheChiffon, UK.

The use of hedges is a common politeness strategy that attenuates the threat to face by tentativizing the illocutionary force underlying the utterance. As Brown and Levinson explain (1987:145), a hedge is a particle, word or phrase that modifies the degree of membership of a predicate or a noun phrase in a set; it says of that membership that it is partial, or true only in some respects (...). The following speaker tries to redress the positive face of fellow-commentators by pretending not to be certain of his/her disagreement. Hence the use of I dont know, all that, just and well:

I dont know if I am all that against body shaming. This is not just very unattractive, its a serious health issue. What ever happened to the days of old when women were normal sized with curves? Im not talking about the curves of Mt Everest but well, just nice. Now its either stick thin to the point of bones or so fat you want to throw up! – Carer, Austin

Along similar lines, the following comment includes such hedges as I wish people would stop trying , instead of using, say, a direct imperative (Stop trying ):

I wish people would stop trying to make out like its fine to look this way, its not natural. – Lucy, NY

A common discursive strategy found in the corpus is disagreeing by agreeing. This of course helps save the face of the hearer whose opinion we do not actually share. Brown and Levinson (1987:114-5) refer to pseudo-agreement in situations where a speaker begins but stating agreement but carries on to state his own opinion which may be completely contrary to that of the first speaker. The use of but (or any other adversative conjunction, like however) usually ensues. But is actually a key marker of disagreement. In grammar, it is the quintessential oppositional particle, and in pragmatics its impact depends on the position within the utterance. The two following cases both employ but following the explicit use of the verb agree:

I agree that women are under a lot of pressure to be perfect and I myself constantly feel pressure to lose weight in order to effectively be a better person but this girl is disgusting. – mimi, surrey.

Cmon, as a woman I have to agree that if I was married to someone who let themselves go that badly, I would look elsewhere, too. A size 12 is one thing, but morbidly obese is another. Its unhealthy and unattractive, and if I were to get that big not due to a medical condition, I wouldnt blame my husband for leaving me. – Lynn, Tampa, Florida, USA

The examples of disagreement through pseudo-agreement abound in the corpus. Consider the following reply to a previous comment, which is itself a disagreement hedged with an apology (Im sorry, no one should be proud of being over weight – laci, Essex):

Agreed. However, no one should be proud of being underweight, either. Both extremes present health issues, but being very thin is sold as beauty in todays society. – Just Sayin, USA.

A similar dyadic exchange takes place when a female commentator criticizes men for being shallow (Most men I feel are just shallow and do not think with their brain but what is between their legs! – Emma, Kent):

Emma, whilst I agree that there are men who are shallow, I can also say that there are women who are the same. Women also make catty remarks about men AND other women. – Bloke, Here

Other expressions of pseudo-agreement do not use the verb agree explicitly:

I can see all the moral problems but that is a seriously funny ad! – JJ, Sydney.

Im all for the fact that woman come in all shapes and sizes but when you know its interfering with your health, its time to sort it out. – Me, Essex.

Incidentally, the use of no, the ultimate disagreement marker, may actually mean yes. Consider a possible reply to the statement: She is not healthy. Saying No, she isnt is actually equivalent to Yes, youre right. The following passages use no as expression of agreement followed by but and the corresponding disagreement (which in the first example ends on a rather impolite interjection – Jeeze grow up):

As for the size of the woman, no she is not a healthy size at all (however some men do like this) but do people on here have to remark about it like theyre still in primary school? Jeeze grow up. – FW, UK

No, being morbidly obese is not healthy but its not your business either. – See it all the time, USA

Occurrences of negative politeness bear on linguistic strategies directed at respecting the recipients freedom of action, that is, their negative face, their wish not to be intruded upon or hindered. Cases of disagreement being mitigated with negative politeness are not abundant in the corpus, but they do exist. The use of apologies is a typical case of negative politeness, as Brown and Levinson state, and they pop up now and again:

Sorry but size 32 is not beautiful- Deeze, North.

Im sorry no one should be proud of being over weight – Laci, Essex

Beauty is health, and whether you be under or overweight you just do not fall in the healthy category, sorry! Lets stop kidding ourselves! – Lee, London

The use of sorry is sometimes strengthened by an affectionate term (love, Jackie), again with ironical tinges:

Sorry love but if my nearest and dearest became a size 32 through simple over-eating I would definitely go get a new one.

No, love, sorry, you are NOT beautiful. You are obese and that is UGLY – Louise, Gillingham.

Sorry, but someone this fat is more often seen as horrific by the general populace than as, *gag*, beautiful. Saying this woman is beautiful and attractive is like saying the same thing of a stumbling drunk or Oooh look at the handsome meth-head! Sorry Jackie – youre horribly obese and theres nothing attractive about it. – Shwa, Denver,

A different discursive situation is the following. By telling (fat) female readers that nobody is preventing them from being fat, the commentator hedges his disagreement that obesity may be attractive, thus expressing his attempt to protect their negative face. In other words, he expresses his respect for their freedom to be as they prefer:

A size 2 woman who sees this ad sees the message: If I dont stay small, he will cheat. Sounds like its working to me. Nobodys telling you that you cant be fat, ladies. Just dont expect that men will look at you as if youre not. Its that simple. – John, Northampton, PA USA

5.4 Foregrounded disagreement: explicitness and directness

Scotts (2002) category of foregrounded disagreement, later taken up by Walkinshaw (2011), echoes Brown and Levinsons bald-on-record strategies for doing an FTA, which involve doing it in the most direct, clear, unambiguous and concise way possible (1987: 69). The reasons Brown and Levinson offer to explain such strategies – urgency, efficiency, negligible threat to face and vastly superior power of the speaker (ibid.) – differ from the ones Locher (2004: 143) presents to account for what she calls unmitigated disagreement:

a) when it is more important to defend ones point of view than to pay face considerations to the addressee (see also Kotthoff 1993);

b) in contexts where the relationship of the interactants minimizes the potential risk of damage to the social equilibrium;

c) when the speakers wish to be rude, disruptive or hurtful (see also Beebe 1995 and Culpeper 1996)

In the Mail Online corpus, it seems that overt impoliteness results from the spatial and temporal discontinuity of the verbal exchange, together with its anonymity. As communication is not face-to-face, with no eye contact or personal knowledge of the interactants, face concerns seem to weaken. Anonymity, in particular, seems to invest speakers with a certain sense of power, which is also linked to the notion that no retaliation – apart from a verbal one – is possible on the Internet. Curiously, Brown and Levinson (1987: 97) also mention this possibility when they state: non-redress occurs [...] where Ss want to satisfy Hs face is small, because S is powerful and does not fear retaliation or non-cooperation from H.

Some disagreements are so direct that the speaker simply states: I dont agree with you. This is the case of the following comment, which is a reply to an earlier comment, referred to above (Im all for the fact that woman come in all shapes and sizes but when you know its interfering with your health, its time to sort it out. – Me, Essex)

Dont agree with you. Size 16-18 is fine... there are a bunch of 16s in our womens rugby team who are fitter than the average man tbh [to be honest] and they can all tie their boots up. – Man Of The People, UK

Other explicit disagreements are simply an interjection (of repulsion and nausea):

Yukeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee – Bob, England,

Albeit explicit too, the range of other bald-on-record strategies used in the corpus to express disagreement is slightly more elaborate, including lexical choice meant to demean the hearers face. Adjectives, in particular, are an easy way to foreground disagreement:

The male mouthpiece for this dating site sounds like a dirty, misogynistic little creep and the words on that advert are utterly offensive and demeaning to women. – FW, UK,

Imagine what the dog-faced men who use this site and mock this woman look like? No, dont, it will put you off your lunch....- Violet Brown, Birmingham

Lol. Youd have to be really really sad to engage in anything like this – male or female!!!!! – Bexxx, LDN

Wow and men really visit that site, they must be short-sighted or desperate!!!!- Dodger, Staffordshire, England

Disgusting. Im thinking that if anyone finds that sexy they are seriously insecure with themselves. – Silvermist, Capo Beach

Completely reprehensible. Perhaps his next campaign could feature an amputee or a burns victim. – Lola, Manama

Sickening, all around. – Pauline, Washington

Juicy jackie.com??? I feel sick at the very thought. – Nobody, Bristol

That is frightening. She should be ashamed of herself for looking that way. Even a genetic predisposition to being overweight does not explain a woman weighing 400 lbs. – Charlene, Arlington, tx, usa

Besides adjectives, the choice of nouns can also be a concise way of disagreeing – and insulting, by the way:

She says the ad is yet another unwelcome case of body shaming. She must be an idiot then! What did she think was going to happen when she posed for the photographs? – PC99, UK

Calling Jacqueline a whale, which can be regarded as a metaphorical strategy for the speaker to go off-record, as we saw above, also occurs in obviously on-record passages of explicit disagreement. In particular, the use of the noun whale together with the adjective beached happens three times, and in all of them the disparaging intention is all but obvious:

Somehow I find it hard to feel sorry for a beached whale posing in lingerie. If she didnt know how dreadful she looked when it was taken, she is more stupid than she looks, and that is quite a bit. You cant get that fat without eating until you are bloated time and time again. She is a disgusting piece of work. – Brian Williams, Dover

Who was talking about rugby players? They are all tall and stocky, but they are not beached whales like this woman. No athlete or sportsperson is-unless they are sumo wrestlers! So dont twist peoples words, face facts. – Hannah, Bham UK

Being that morbidly obese is not attractive in the slightest and its disgusting to see somebody flaunt her misused body. IT IS NOT OKAY to look like a beached whale. Size does matter when it comes down to health, and I have no doubt that her health is slowly deteriorating as we speak. – Appalled, London

The following comment is a reply by a woman to an earlier comment by a man. The use of the sardonic noun billy-no-mates is aggravated by the adjectives sad and lonely, and the noun loser is made all the more aggressive by the use of block capitals:

She should be grateful for any attention she gets. – Alex / Likewise Alex. Only attention youll get are red arrows. But I guess its better than nothing, you sad lonely billy-no-mates. LOSER. – Lou, London

The use of straight imperatives to give advice (which in itself is a threat to the hearers negative face) aggravates the nature of the FTA, as happens in the following example, which exhibits some mitigating input at the beginning (I dont think ) only to go bald-on-record in the second sentence:

I dont think its right that anyone should let themselves get in this state (medical conditions excluded) but her condition clearly starts at 6am when she opens the fridge door. Gain some willpower and self respect and stop complaining. – Mimi, Surrey

One of the strategies Brown and Levinson stipulate for protecting the hearers negative face is Dont presume /assume, which includes avoiding presumptions about H, his wants, what is relevant, or interesting or worthy of his attention – that is, keeping ritual distance from H (1987: 144). In the next passages, the speakers explicitly presume to have knowledge about the recipients personality, likes, preferences and way of being. At the same time, they ostensively violate one of Leechs (1983) politeness maxims, the approbation maxim (minimize dispraise of other):

How can you have so little self respect to let yourself end up like that! – Rod Steele, Shaftesbury

She looks like that because of gluttony, self-indulgence and a lazy refusal to exercise. If she says differently, shes lying. – Pete, Brighton

An interesting form which explicit disagreement assumes in the corpus is what Goodwin and Goodwin (1990: 97) call content shift within argument.In the following passage, the speaker openly disagrees with the interpretation the readers have made of the article and performs a repair strategy (Sacks et al. 1974) to restore what she believes is the right argumentative line:

Missing the point people!!!!!! This is not about the size of the lady involved. It is about the use of her image to promote infidelity; more to the point a website that helps you actively go out and look for someone to cheat with. Fat or thin how happy would you be with that? – Polly, Germany

Much along the same lines, the comment shown next starts with a foregrounded expression of disagreement, in which the adverb of negation is signaled in block capitals, followed by a repair utterance in which the speaker gives her own reading of the subject in hand:

Whether shes fat or not is NOT in question here. Its about the fact that sleazy Ashley Madison used her image WITHOUT her permission and did so in an embarrassing and derogatory way. – Jade, Los Angeles, USA

It should be noted that these cases of different topics being raised in the middle of an argument are a symptom of disaffiliation not only towards one party involved in the dispute, but also with its opponent party. Maynard (1986) calls this phenomenon non-collaborative opposition and explains it as follows:

In the first place, we have seen that disputes, although initially produced by two parties, do not consist simply of two sides. Rather, given one partys displayed position, stance, or claim, another party can produce opposition by simply aligning against that position or by aligning with a counterposition. This means that parties can dispute a particular position for different reasons and by different means. It is therefore possible for several parties to serially oppose anothers claim without achieving collaboration. (Maynard 1986: 280)

One final aspect concerning the explicit expressions of disagreement in the corpus deserves mention. It is a fact that, as Locher has remarked (2004: 113), speakers often give personal or emotional reasons for disagreeing. And, by opening up about themselves and actually assuming a self-disclosure mode, they make their face more vulnerable. That is perhaps the reason for the defensive stance which is noticeable in utterances such as the following:

I am a big and beautiful woman. I am comfortable in my skin and I refuse to be ashamed. If anyone is gross it is those that destroy others self-confidence with their hateful cruel words. There is beauty in ALL body types, skin color, and gender. If you cant see that, something is wrong with you. – Carol, Chicago

A comment by a male participant who signs Slim Jim Loves Fat Pat, and which reads Most women over size 14 are clinically obese (do the math if you dont believe me – BMI of 30 or more is obese), receives a set of emotional, personal responses which express utter disagreement:

I think that statement is downright rude! I am a 19-year-old size 14-16 woman. I am by no means obese with a BMI of 21! Size 14 women can just be big boned or curvy women. I have a 26 waist and naturally large hips, does that make me fat, just because Im labelled with a number 14?! And yes, you said MOST women, but I highly doubt Im alone. – Elouise, Cambridge

The next female reader also replies to Slim Jim by giving personal, detailed information about her own body size and weight, and by insisting on the repair strategy of claiming that she is healthy rather than obese:

Slim Jim – size 14 women are not obese, unless they are deluding themselves about their clothes size. I am a size 12-14 with a BMI of 24.9 which makes me just about within healthy range. Before I had children, I was a size 10 and my BMI was 20, which made me very slim and well within the healthy range. – Kath, Cardiff

Personal statements can take the opposite stance: instead of expressing disagreement towards intolerance to obesity, they express disagreement towards its tolerance:

I was bitterly ashamed of myself when I let myself go to a size 18 and quickly snapped myself out of it back to a 10/12. Being life threateningly overweight is not attractive. This woman is just as bad of a role model as the dangerously underweight models, if not worse. – Rebecca, Gloucestershire

Likewise, the following respondent disagrees with all those defending fat people by setting her own example: that of a person who is trying her hardest to lose the excess weight:

Since giving up smoking I have put on a bit of extra weight but am nowhere near this size.......And I am trying my hardest to get rid of the excess pounds. I know Im overweight and feel uncomfortable but she must find problems in a lot of the normal things she has to do everyday. – Sue, Oxford

Interestingly, the following commentator seems to be aware that personal, emotional comments regarding Jacqueline tend to come from people who have weight issues themselves. So, she anticipates – and corrects – the potential wrong inference as follows:

Just listen to yourselves on here. Jacqueline makes a lot of very good points about how the female body is perceived and she is right. We have young girls who are absolutely obsessed with their shape and weight. And before some smart alece [sic] says I bet you must be fat, no Im not fat at all, far from it – Female, UK

Finally, a very curious explicit disagreement strategy is the blunt expression of approval of Jacquelines looks. In a forum that challenges obesity in all its aesthetic, psychological and health-related aspects, to say that she is, indeed, attractive is a major rebuttal of the opinions expressed. Next is a sample of utterances that assume an adversarial stance by actually agreeing, rather than disagreeing, with the main topic of the text – that of obesity:

More to love I guess. – anita daeoph, usa

Hmmmm, full complete bedfeast !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! yummy !!!!!!!!!!! – Tony, Essex

Jackie certainly is juicy 8] – fezza, England

Own goal surely, theres nothing scary about the gorgeous Jacqueline. – Mark, Huddersfield

I like em rotund!! – Bejeeeeeeesus

Conclusion

This article has investigated the expression of disagreement in a corpus of online commentaries to a news report case. Several patterns have emerged in what has proven to be a good example of conflict talk, with alignments and confrontations taking place along the adversarial spectrum. However, the management of the oppositional input has also addressed face concerns, and rather often for that matter, though by no means always.

On an interpersonal level, the corpus has proven to belong to the category of multi-party argument (Maynard 1986, Goodwin and Goodwin 1993: 100) even though dyadic sequences were also identified. In other words, speakers interacted either by replying directly to another speakers utterance or by posting unaddressed comments.

In terms of content, the complexity of the analysis has involved a few concurring factors. First, the construction of the argument revolves around more than one topic. The initial cue, offered by the newspaper itself, is that big is beautiful, but the range of disagreement expands to other topics, such as the health-problems regarding obesity, the objectification of women, man-woman relationships, adultery, pornography and hypocrisy. This I have proposed to call multi-topic argument. Its complexity derives from the fact that an initial topic prompts the appearance of several topic strands in an equally complex sequence: being raised, debated, dropped and recovered along the argumentative axis. Another analytical challenge has been the fact that the speech act of disagreeing may be mixed with other forms of illocutionary force. Indeed, the disagreements occurring in the corpus often overlap with other speech acts, such as criticising, protesting, reprimanding, etc, making the illocutionary boundaries somewhat vague. Thirdly, the variety of topics has shown to be related to a broad range of reasons for agreeing or disagreeing. From ethical and moral reasons to health reasons, social reasons and aesthetic reasons, the opinions expressed reveal a great assortment of motivations for stepping forward and expressing a contrary opinion. Crucially, personal reasons rank high, as is the case of fat people strategically siding with the obese model and confronting her critics (on disagreements as strategic moves, see Upadhyay 2010, above).

Interestingly enough, the representations of femaleness that emerge throughout this complex argumentative process seem to reify, by and large, existing stereotypes of physical perfection and desirability. In fact, although a few voices do get to be raised in favour of alternative standards of female beauty and attractiveness, the overwhelming bulk of comments prove to support the widespread ideals of thinness and slenderness. Besides this reinforcement of prevailing conceptions of womens body image, the texts also denote the surfacing of another sort of stereotype, that of the equation of the female subject with a sexual object. Indeed, Jacquelines side professional activities are more often than not viewed as conflicting elements that undermine her cry for justice and reduce the legitimacy of her claims. Had she been a married mother of four, perhaps the opposition to her complaints would have been less noticeable.

The diversity of ideological, psychological or personal motivations detected has revealed two types of interpersonal stance: a defensive stance (typically exemplified by obese readers) and an aggressive one. Whatever the case, the analysis has confirmed Angouri and Lochers (2012: 1549) claim that disagreeing does have an impact on relational issues (face-aggravating, face-maintaining, face-enhancing). The situations in which replies – including insulting ones – are directed at specific interactants illustrate an aggressive attempt at debasing the opponents face. Other comments, meanwhile, have revealed face concerns of various strengths.

The analysis has shown that the expression of disagreement in the corpus ranges from backgrounded forms, that is, covered, implicit, or mild disagreement, to foregrounded forms, i.e., overt, explicit, or unmitigated disagreement (Scott 2002), admitting however in-between manifestations, hedged with positive and negative politeness (Walkinshaw 2011). Occurrences of overt impoliteness, with expression of bald-on-record rebuttals, provocations and even insults may be related to the anonymity of its participants and the discontinuous character of the interaction, both in spatial and temporal terms, which encourage the abandonment of face concerns (Donath 1999, Eisenchlas 2011, Yus 2011). Knowing that no retaliation is possible, speakers feel free – and powerful enough (Brown and Levinson 1987: 97) – to attack their opponents face.

Finally, the analysis has suggested another – crucial – explanation for the impoliteness occurring in the corpus: namely, what I propose to call, along Leechs lines (1983: 133), third-party factor. Disagreeing with, criticising, debasing and deriding an absent party is much less risky than doing so in face-to-face conversation. The fact that Jacqueline is not taking part in the polylogue makes her face more negligible, and it strengthens the respondents boldness to show their disaffiliation. This may explain the openly conflictual and confrontational nature of some of the comments, which the protocol ruling over regular daily interaction usually tends to soften.

Bibliography:

Aitchison, J. and Lewis, D. M. (Eds.) (2003), New Media Language. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Angouri, Jo (2012), Managing disagreement in problem solving meeting talk. Journal of Pragmatics. Volume 44, Issue 12, September 2012, 1565–1579. [ Links ]

Angouri, Jo and Locher, Miriam A. (2012), Theorising Disagreement. Journal of Pragmatics. Volume 44, Issue 12, September 2012, 1549-1720. [ Links ]

Atkinson, Maxwell & Heritage, John (Eds.) (1984), Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: C.U.P. [ Links ]

Austin, J. L. (1962), How to Do Things with Words. Oxford: O.U.P. [ Links ]

Bargiela-Chiappini, Francesca (2003), Face and politeness: new (insights) for old (concepts). Journal of Pragmatics 35: 1453-1469. [ Links ]

Baron, Naomi (1998), Letters by phone or speech by other means: the linguistics of email. Language and Communication 18: 133-170. [ Links ]

Baron, Naomi (2003), Why email looks like speech. In: Aitchison & Lewis (Eds.), pp. 85-94. [ Links ]

Blum-Kulka, Shoshana (1990), You dont touch lettuce with your fingers: Parental politeness in family discourse. Journal of Pragmatics 14 (2): 259-288. [ Links ]

Bolander, Brook (2012), Disagreements and agreements in personal/diary blogs: A closer look at responsiveness. Journal of Pragmatics. Volume 44, Issue 12, September 2012, 1607-1622. [ Links ]

Brown, Penelope & Levinson, Stephen (1987), Politeness: Some Universals of Language Usage. Cambridge: C.U.P. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2000), The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell. 2nd Ed. [ Links ]

Cherry, Roger D. (1988), Politeness in written persuasion. Journal of Pragmatics 12: 63-81. [ Links ]

Chilton, Paul (1990), Politeness, politics and diplomacy. Discourse and Society, Vol.1(2): 201-224. [ Links ]