Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.109 Lisboa dez. 2018

https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis13745

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

The impact of socio-economic factors on the health of the Moroccan immigrants in Navarra (Spain)

O impacto dos fatores socioeconómicos na saúde dos imigrantes marroquinos em Navarra (Espanha)

El impacto de factores socio-económicos en la salud de los inmigrantes marroquíes en Navarra (España)

Impact des facteurs socio-économiques sur la sante des marocains émigres en Navarre (Espagne)

Carolina Montoro-Gurich1

1 Professor of Human Geography, University of Navarra, Campus Universitario, 31009 Pamplona, Navarra, Spain. E-mail: cmontoro@unav.es

ABSTRACT

This paper analyses from a perspective the social determinants, socio-demographic and lifestyle factors that affect the health self-appraisal of immigrants of Moroccan origin living in the Spanish region of Navarra, using data from a cross-sectional ethnosurvey conducted in 2013. Results show, contrary to the literature, that women have a better health status variation than men, probably because men have a higher age profile and a longer stay in Spain. The binary logistic regression reveals important differences in the likelihoods of finding specific determinants of the health by sex. Paid employment is the most positive, significant factor for health among women. Close social ties with other Moroccan immigrants, living in an inexpensive old house and, to a lesser extent, having a secondary level of educational achievement show the highest probabilities for men.

Keywords: Immigration and health; Moroccan immigrants; Spain; social determinants of health.

RESUMO

Neste trabalho, analisam-se os determinantes sociais, sociodemográficos e de estilo de vida que influenciam a autoperceção de saúde dos imigrantes marroquinos. Para tal utiliza-se informação de um inquérito etnográfico transversal aplicado em 2013 na região espanhola de Navarra. Os resultados mostram que, contrariamente à literatura consultada, as mulheres apresentam uma variação do estado de saúde melhor do que o dos homens, provavelmente porque estes têm um perfil etário mais envelhecido e vivem há mais tempo em Espanha. A análise de regressão logística binária revela importantes diferenças nas probabilidades estatísticas no que diz respeito aos determinantes específicos sociais por sexo. Ter um emprego remunerado é um fator que tem uma importância significativa e positiva para a saúde das mulheres. Estreitar relações sociais com imigrantes marroquinos, viver numa casa antiga e económica, em menor grau, ter uma formação educativa de nível secundário são fatores com maiores probabilidades para os homens.

Palavras-chave: Imigração e saúde; imigrantes marroquinos; Espanha; determinantes sociais e de saúde.

RESUMEN

Este trabajo analiza los determinantes sociales, socio-demográficos y de estilo de vida que afectan en la autopercepción de salud de los inmigrantes de origen marroquí residentes en la región española de Navarra empleando información de una encuesta transversal etnográfica desarrollada en 2013. Los resultados muestran, en contraste con la literatura consultada, que las mujeres tienen una variación del estado de salud mejor que los hombres, probablemente porque éstos tienen un perfil etario más elevado y llevan más años viviendo en España. El análisis de regresión logística binaria revela importantes diferencias en las probabilidades estadísticas de encontrar determinantes específicos por sexo. Tener un empleo remunerado es el factor significativo y positivo más importante para la salud entre las mujeres. Estrechas relaciones sociales con otros inmigrantes marroquíes, vivir en una casa antigua y económica y, en menor grado, tener un nivel educativo de secundaria son los factores con las mayores probabilidades entre los hombres.

Palabras clave: Inmigración y salud; inmigrantes marroquíes; España; determinantes sociales de la salud.

RÉSUMÉ

On analyse ici des facteurs, à partir d’une enquête réalisé en 2013 entre ces immigrants. Il en résulte que les femmes présentent un maillé état sanitaire que les hommes, probablement parce qu’elles sont plus jeunes et séjournent depuis moins longtemps in Espagne. L’analyse des données indique une inégale possibilité de détermination des différences sanitaires selon le genre L’emploi salarié est, pour les femmes, un facteur positive important. Pour les hommes, les facteurs principaux sont lexistence de relations étroites avec dautres immigrés marocains, linstallation dans de vieilles bâtisses bon marché et, à un moindre degré, une éducation de niveau secondaire. On en conclut que les implications économiques de la vie journalière affectent la santé des immigrants marocaine des deux sexes.

Mots clés: Immigration et santé; immigration marocaine; genre; Espagne; facteurs sociaux de la santé.

I. INTRODUCTION

The process of immigration and settlement in a new society leads to changes of different kinds and degrees of significance in the life and lifestyle of an immigrant. Geographical mobility, poverty and/or job precariousness, poor housing, lack of family and social support, legal and linguistic difficulties, cultural contrasts, feelings of estrangement, lack of access to health services, etc., can have an impact on the health and healthcare of immigrants (Davies, Basten, & Frattini, 2009; Oliva & Perez, 2009; Bhopal & Rafnsson, 2012; Ronda et al., 2014; Castañeda et al., 2015). Understanding the health status and the factors that affect an immigrants health is of great interest for attending to the needs of migrants, facilitating their integration and reducing health inequalities that might affect this population (Solar & Irwin, 2010; Bhopal, 2012).

Studies carried out on the relationship between immigration and health status thus far have yielded a variety of results. In some cases, immigrants are found to have a better health status than native populations, whereas this relationship is reversed in others (Nielsen & Krasnik, 2010; Foets, 2011; Ullmann, Goldman, & Massey, 2011; Villarroel & Artázcoz, 2012). The categorization of immigrants as a homogeneous group may be the main bias influencing the results because it assumes that there are no differences in epidemiological and health patterns, cultural perceptions about health and illness, socioeconomic status, etc., among origin countries (Castañeda et al., 2015; Gazard, Frissa, Nellums, Hotopf, & Hatch, 2015). Economic migrants, whose main reason to migrate is a lack of job opportunities and a poor standard of living in their countries of origin, are among the migrants with an increased risk of poor health. This is due to the poor socioeconomic conditions in which they lived in their country of origin and they frequently live in the hosting countries (Williams, 1998; Borrell et al., 2008; Phelan, Link, & Tehranifar, 2010).

Another significant bias is the inclusion of the variable “sex” as a simple adjustment in the analysis, which presumes that the factors influencing the association between immigration and health are similar for men and women. However, the health social determinants differ by gender: research has shown that women are more vulnerable than men to health-related inequalities (Sen & Östlin, 2007; Hill, Angel, Balistreri, & Herrera, 2012). Factors such as lower levels of educational achievement, exploitation at home and/or at work, inequality in the distribution of power, discriminatory values and practices, etc., are provided in the literature as an explanation for this reality. Although not all these factors might be present in all migrant populations, it is likely to find them among economic migrants. For these reasons, conceptual models of analysis that frame inequality in relation to gender are required to account for the social determinants of heath inequalities (Arber, 1997; Llácer, Zunzunegui, del Amo, Mazarrasa, & Bolumar, 2007; Malmusi, Borrell, & Benach, 2010).

Spain, historically a country of emigration, begun to receive an intense influx of migrants by the end of the twentieth century due to its economic development (Arango & Martin, 2005; Reher & Requena, 2009). Between 2000 and 2008, nearly 6 million people immigrated to Spain, and by 2008 the proportion of the Spanish population born in a foreign country reached 13.3%. With the economic crisis, and until 2014, the migrant balance was again negative, reaching the highest peak of emigration in 2013. Even though, the proportion of the Spanish population born in a foreign country has remained quite stable up to the present, being 13% in 2013 and 13.1% in 2017 (INEbase)i.

Given that Spain is a country where the phenomenon of immigration is relatively recent, little is known about the relationship between immigration and health and of the impact of the social, economic and living conditions of immigrants on their health. Nevertheless, research has found that the health levels of the immigrant population are worse than those of the local population, even when the educational level is higher among the former than the latter. The reason for this is a strong association between poor living conditions in socio-economic terms (low levels of income, frequent unemployment) and level of health (Borrell et al., 2008). Other social determinants relevant in this association are low levels of social support and experiences of social discrimination among the migrant population (Malmusi & Ortiz-Barreda, 2014). Moreover, immigrant health tends to decline over time after their arrival, despite the improvement in socioeconomic conditions. Finally, the most tested indicators – mental and perceived health – are worse in the immigrant population than among the local population, in particular, among immigrant women (Malmusi et al., 2010; Villarroel & Artázcoz, 2012).

On the other hand, Morocco is an important source of economic migrants because as a middle-income state its economic and infrastructural development is sufficient to loosen bonds to local people and institutions but, not enough to provide full employment thus increasing internal and international migration to nearby developed nations (Massey, Connor, & Durand, 2011), among them Spain. Spanish habitants born in Morocco have remained stable all along this period, around 11.8% of total Spanish habitants born outside Spain in 2008, 12% in 2013 and 11.6% in 2017 (INEbase)ii.

The community of Moroccan immigrants is characterized by being one of the most cohesive and, at the same time, one of the most isolated from the rest of the population in Spain. In comparison with immigrants from other countries, Moroccans have low rates of economic activity and labour occupation -especially due to the very low level of female economic activity-, a limited command of the Spanish language, a small volume of mixed couples and, they awake little sympathy among Spaniards (Cebolla-Boado, Requena, & Revenga, 2009). In addition to this, Moroccan show little interest in taking part in associations that are not aimed at the immigrant population and, a meagre investment in real estate or business (Montoro-Gurich & López Hernández, 2013).

Concerning health issues, although contrasts between regions of origin have received limited research attention, significant differences have emerged. In this regard, the Moroccan immigrant population shows lower levels of perceived health than other groups of migrants, and the perception among Moroccan women tends to be more negative than that among Moroccan men. A possible explanation is in the most widespread gender roles in this population, in which women have a scarce leading role in migratory projects (Salih, 2001; Haas y van Rooij, 2010). Also to the fact, that in Spain they frequently have access to a limited and precarious labour market with few opportunities for promotion, which includes tasks with little social value, such as domestic service and the care of dependent persons (Rodríguez Álvarez et al., 2009).

From a geographical point of view, the Moroccan immigrant population is not distributed homogeneously throughout the Spanish territory. It is most abundant in the Mediterranean coast, Madrid and its surroundings and, the axis of the Ebro Valley, in addition to the archipelagos and the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla (Pons Izquierdo, 2014). The Comunidad Foral de Navarra, included in the axis of the Ebro Valley, is an interesting case study. In 2013, with 14% of the immigrant population, it held a modest tenth position in the ranking of autonomous communities; however, it was the third in terms of the weight of immigrants from Africa, only behind Murcia and Catalonia. Specifically, 11.4% of the immigrants residing in Navarra had been born in Morocco (Estrategia Navarra para la Convivencia, 2014).

The purpose of this paper is to analyse the social determinants, socio-demographic and lifestyle factors that affect the health self-appraisal of immigrants of Moroccan origin compared with health self-appraisal before migration. It means that the analysis and interpretation of differences in the health self-appraisal between these women and men receive specific attention. First, because the immigrant’s sex is not included as an independent variable in the statistical model, but as specific models, separately, for women and men. Second, we believe that the explanation for these differences is based in gender inequalities within this specific immigrants group. This analysis draws on a case study of Moroccan immigrants resident in the Spanish region of Navarre in 2013. The marked demographic presence of this population in Navarra and the characteristics of internal cohesion and socio-cultural isolation indicated above make us believe that understanding the determinants that affect their health can be a factor of added value in integration policies addressed to this population.

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study design and sample

The information used for this analysis comes from the survey conducted for Moroccan Migration in Spain: origin and destination perspectives project, in which –thus far– 262 Moroccan immigrants resident in the region of Navarre have been interviewed. The ethnosurvey (Massey, 1987)iii from the Office of Population Research at the University of Princeton was adapted for this purpose. This is the first time it has been used in the Hispano-Moroccan geographical and cultural environment. The questionnaire has a semi-structured format that enables flexible interviews. The head of household is interviewed and provides information about everyone living with him, as well as about himself. Socio-demographic data and the migration history of each person in the household were obtained, followed by a detailed employment history, data about resources acquired, use of social services and information about health. Regarding the physical condition of the interviewee, in addition to asking for the perceived health status prior to migration to Spain and the present perceived status, the survey collected data on stature, weight, smoking habits, and suffering from different illnesses.

The Spanish Population Register (“Padrón”) has been used to locate the immigrant population born in Morocco and resident in the municipalities of Navarre to establish the number of households to be interviewed: 209 households, in which lived a total of 839 people (8.5% of Moroccan population living in Navarra). Data were collected through face-to-face interviews at home between the end of October and the beginning of December 2013. A 37% of interviews took part in Pamplona (the capital) and its surroundings and, a 63% of them in the Ribera (the South of Navarra), according to geographical distribution of the Moroccan population.

In the Moroccan population, the man is culturally “the head of the household” – even when he was absent, and the gender patterns are clearly differentiated (Salih, 2001; Heering, van der Erf, & van Wissen, 2004; Pels & de Haan, 2007; Soriano Miras, 2008). In the process of obtaining the data, women were found to occupy the position of “the head of the household” only in 32 out of 209 cases. So as to gain a broader perspective on the Moroccan migration process, the decision was taken to interview some women who are not heads of household (53 individuals), yielding a total of 262 interviews in all. Thus, 177 surveys were carried out with men and 85 with women.

Besides, a further condition for case selection was that the interviewee be over 14 years old when he/she migrated to Spain so as to avoid including very young people in the analysis, whose health status self-appraisal before migrating might raise doubts because of her/his youthfulness. The final sample of cases used in the analysis comprises a total of 257 individuals, 176 men and 81 womeniv.

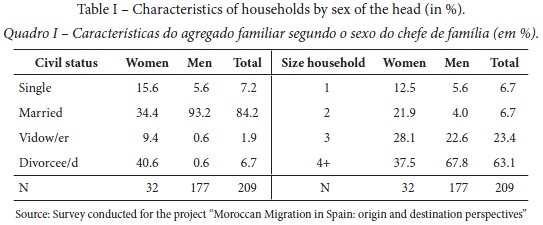

Some details about the living and working characteristics of this population are given in table I and table II. Table I shows some characteristics of households by sex of the head (civil status and size). The households headed by the women are very different from households headed by the men. Moreover, 75% of households headed by the men are of nuclear type (couple with children) compared with 9.4% of those headed by women; 37.5% of households headed by women are single parent families (mother with children) compared with 0.6% of those headed by men.

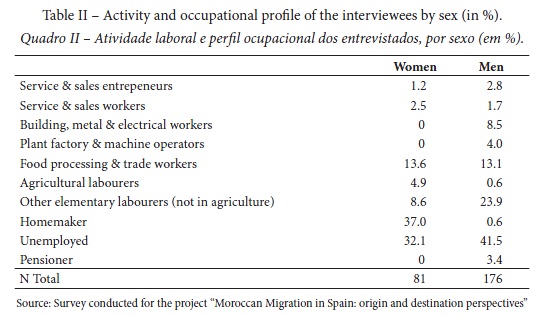

Table II gives detail about the occupation and economic status held by the interviewees at the moment of the survey, differentiating by sex. This is an important feature given the economic character of Moroccan migration, and it can be surprising to find such a big percentage of unemployed people. In Navarra, the Moroccan occupational profile is strongly linked to agricultural activity and the canning industry, which are highly seasonal. Moroccan workers alternate work periods with others of unemployment on a seasonal, and stable, basis. The survey was conducted in two stages, end of October and mid-November to mid-December, a period of low activity for these sectors, and this is reflected for example in the extremely low percentage of men classified as agricultural labourers. This table also show important differences in the activity and occupational profile by sex, for example more than a third of women are homemakers (37%).

2. Variables

2.1. Dependent variable: Health Index

This paper assumes that the individuals perception of their own health status, at the time of the survey as well as that just before coming to live in Spain, is a valid indicator to measure the reality. In fact, self-perceived health status is one of the most commonly used indicators in analyses of inequalities in health. Besides, self-perceived health is regarded as a reliable indicator of health status, morbidity and mortality, and may be taken as such for migrant minorities as well (Rodríguez Álvarez, Lamborena, Senhaji, & Pereda Riguera, 2008; Nielsen & Krasnik, 2010). Its defining characteristic is subjectivity because the person is giving their own ’internal’ understanding of their health, as opposed to external views that are based on observations of doctors (Constant, García-Muñoz, Neuman, & Neuman, 2014). Researchers have used this indicator to examine the relationship between health and a wide range of social and economic factors, including income, education, socioeconomic status, and early life experiences (Au & Johnston, 2014).

Both current and prior to migration self-reported health status was obtained by asking the respondents to describe their health as ’very good’, ’good’ ’fair’ or ’poor’v. Comparing the current self-reported health status with the one prior to migration, three possibilities stand out: both statuses are equal, current health perception is better than that prior to migration and, current health perception is worse than that of prior to migration.

To analyse the social determinants, socio-demographic and lifestyle factors that affect the health self-appraisal these possibilities were combined to construct our dependent variable, named “Health Index”. It has two values: 1, when the health status perception has not changed or has improved, and 0, when the health status perception has worsened since migration.

For the purposes of this analysis, which focuses on an immigrant population of Moroccan origin, the bias found in other studies in which immigrants from different countries were considered as a single category may be regarded as minimised. Moreover, analysis by sex enables us to avoid the bias involved in considering all determinants to be the same and affecting men and women equally and/or in the same ways. At the same time, however, a limitation on this study is that no comparison is drawn between the health status of the Moroccan immigrant population resident in Navarre and a reference population, for instance, a cohort of local people.

2.2. Independent variables

Attention was then turned to the eventual factors that may affect the health status variation and could be obtained from the survey information. The selection of factors was based on an analysis of the research conceptual frameworks relating to social determinants that affect health inequalities (Malmusi et al., 2010; Solar & Irwin, 2010) and, in particular, Arbers model, frequently used in health inequality studies by gender. In the conceptual model outlined by Arber (1997), when people have a partner/spouse, variables related to social capital such as level of education or the employment of the partner/spouse are included. However, given that a significant number of women in our sample did not have a partner/spouse (a 20.1%, compared with a 6.8% of men), the partner variables were excluded.

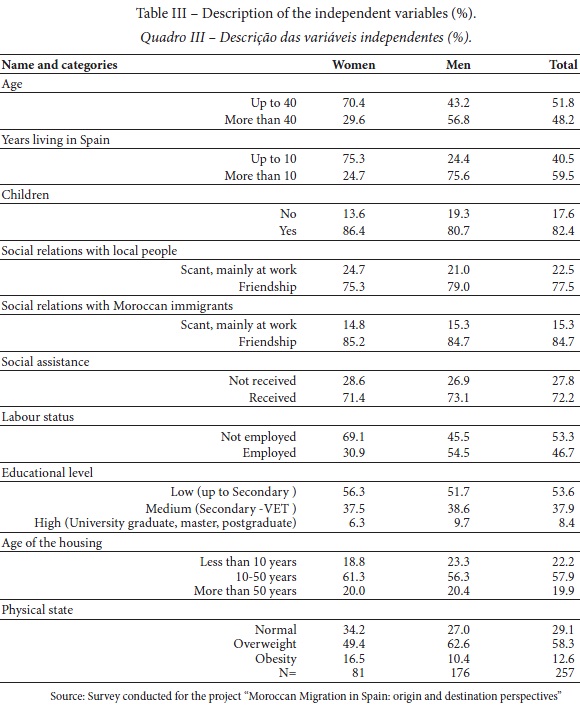

The factors, whose statistical description is given in table III, are:

- This factor was calculated subtracting to 2013 (year of the survey) the year of birth. The variable was dichotomized, taking the age of 40 as a boundary between young and mature population;

- Years living in Spain. This factor was calculated subtracting to 2013 the year of arrival to Spain. The variable was dichotomized, dividing the sample into those who have lived in Spain for more and less than 10 years, considering that this period of time divides new and old migrants;

- Number of children, classified in two categories: having children or not having children;

- Intensity of social relationships with other Moroccan immigrants. The formulation of this question in the questionnaire was: “What sort of relations do you have with other Moroccans?” [Que tipo de relación tiene con otros marroquíes?] and the possible answers were: none or casual [ninguna o casual], only at work [solo en el trabajo], friendship [amistad], intimate [de intimidad o estrecha]. The variable was dichotomized, classifying the relations as scant, mainly at work (when the interviewee asserts that she/he has no relationship or it is strictly a working or a casual relationship) or friendship (when the interviewee affirms that she/he has a friendship or intimate relationship);

- Intensity of social relationships with local people. The formulation of this question in the questionnaire was: “What sort of relations do you have with local people?” [Que tipo de relación tiene con los autóctonos de este país?] and the possible answers were: none or casual [ninguna o casual], only at work [solo en el trabajo], friendship [amistad], intimate [de intimidad o estrecha]. The variable was dichotomized, classifying the relations as scant, mainly at work (when the interviewee declares that she/he has no relationship or it is strictly a working or casual relationship) or friendship (when the interviewee affirms that she/he has a friendship or intimate relationship);

- Reception of some social assistance (yes or no). The interviewee was asked if she/he had ever received or, was receiving any sort of social assistance at the moment of the survey [¿Ha recibido o recibe alguna ayuda?]. If it was the case, she/he was invited to cite which ones [¿Cuáles?]. Social assistance encompasses support measures such as an economic allowance for immigrants at risk of social exclusion (called “RIS”, “Renta de Inserción Social”), an economic support for families having the 4th child (both from the Regional Government of Navarra), dependent child allowances (from the Spanish National Insurance) and, other specific support measures (food assistance, bill payments, medicines, school stationery, etc.) which several NGOs provide. The variable was dichotomized into received or not any social assistance;

- Work status at present time. The formulation of this question in the questionnaire was: “Main current economic activity / occupation” [Actividad económica principal actual / ocupación]. The possible answers included for non-economic activity unemployed, homemaker, pensioner and student; and a wide range of occupations for people in economic activity. The variable was dichotomized into employed or not employed. In the case of women, the category of not employed is composed by homemaker and unemployed; in the case of men, we also find pensioners. There is no case of interviewees being students;

- Educational level. The formulation of this question in the questionnaire was: “Years of education completed” [Años de escolaridad completados]. The possible answers included without studies (0 years), knowing to read and write (1 year), primary school (8 years), secondary school (11 years), vocational education and training (VET) (14 to 16 years), university degree (15 to 18 years), master (19 to 20 years), doctorate (21 to 24 years). The answers were classified into three categories: low, people with primary education or lower; medium, people with secondary studies or vocational education and training (VET); and high, university graduates or postgraduates;

- The formulation of this question in the questionnaire was: “Age of housing” [Antigüedad de la vivienda]. The possible answers included <10 years, 10-50 years and, >50 years;

- Physical condition. The interviewees were asked about their current weight and stature. With this data, the Body Mass Index (BMI) (kg/stature2) has been calculated and the resultant values have been classified according to the nutritional status parameters of the World Health Organization (WHO). It give us three categories: between 18.5 and 24.99, normal; between 25.0 and 29.99, overweight status; and from 30.0, obesity.vi

3.3. Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis chosen has been a binary logistic regression. This kind of multivariate analysis enables prediction of the relationship between the dichotomous dependent variable (same or better health status versus worse health status after migration) and other independent and control variables. In our case, we wanted to study the probability that the health self-perception remained stable or improved (Y=1) as a function of independent X variables such as: “years living in Spain”; “social relationships with other Moroccan immigants”; “age of housing”, etc., since those factors were assumed to be significant. The closer to 0 the Sig. value is, the more likely health status is to remain stable or to have improved.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

According to the bibliography, self-perception of health status is influenced by gender. Generally speaking, women tend to report poorer self-perceptions of health than men (Malmusi et al., 2010; Villarroel & Artázcoz 2012; Ortiz-Barreda, 2014). When dealing with the immigrant population of Moroccan origin, there is no agreement between researchers. Some findings point out that women show a poorer self-appraisal of health than Moroccan men (Rodríguez Álvarez et al., 2009) whereas other conclude that this is not the case (Villarroel & Artázcoz 2012). Another important factor that influences the self-perception of health is time, both expressed in age and time elapsed since migration. In relation to age, the elderly immigrant population are expected to have the most negative perception of their health status; in relation to time since migration, the bibliography finds that the longer since migration, the less likely a positive perception of the variation of the health status will be (Malmusi et al., 2010; Hill et al., 2012).

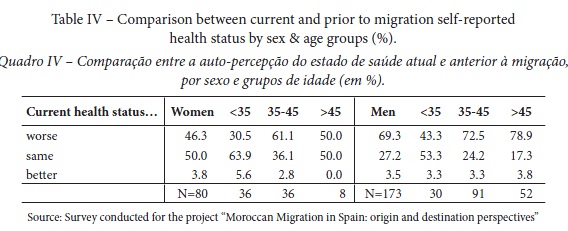

In our sample, the comparison of current and prior to migration self-reported health status shows a more positive appraisal among women than menvii and, among younger than older people. (table IV) A very significant percentage of the Moroccan immigrant population resident in Navarre in 2013 felt that, since their arrival in Spain, their health status had worsened, 46.3% of women and 69.3% of men, compared to a small percentage of people who said that it had improved (3.8% of women and 3.5% of men). However, it is worth mentioning that in the case of women, 50% declare to have the same health status than before coming to live in Spain.

The results may be affected by the fact that the two segments of the population evince different age profiles: the mean age of the men is 41.6 years (standard deviation: 7.686) as compared with a mean age of women of 35.4 years (standard deviation: 7.996)viii. Therefore, on disaggregating the health deviation rate by sex and large age groups, 79% of older males think that their health status has worsened, a proportion which falls to 72.5% among mature males (aged between 35 and 45), and to only 43% of men under 35.

Among women, the relatively small number of individuals aged older than 45 does not enable clear conclusions, but among 35–45-year-old women the perception of worsened health status is clearly more frequent (61% of cases) than among younger women, where the rate falls to 30.4%. In other words, in line with other findings in the research literature, the criterion of a worse perception at older ages seems to be fulfilled, a criterion that applies to the population at large, not only or specifically to immigrant populations.

About the influence of time elapsed since immigration on the individuals self-perception of health status, the results from the Moroccan sample under study show a very different average time of stay in Spain depending on gender: 14.6 years (standard deviation: 5.926) for men, as compared with 8.7 years for women (standard deviation: 4.248) ix. This factor also underlies the finding in this study that men tend to have a more negative self-perception of their health than women.

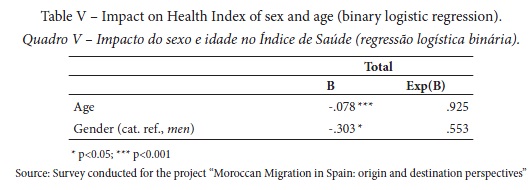

Finally, a binary logistic regression was made to assess the relevance of sex and age in the Health Index. Table V confirms the results obtained in our descriptive analysis. Being male (rather than female) and being older are factors that impact negatively on health, although the effect of age is slightly more significant.

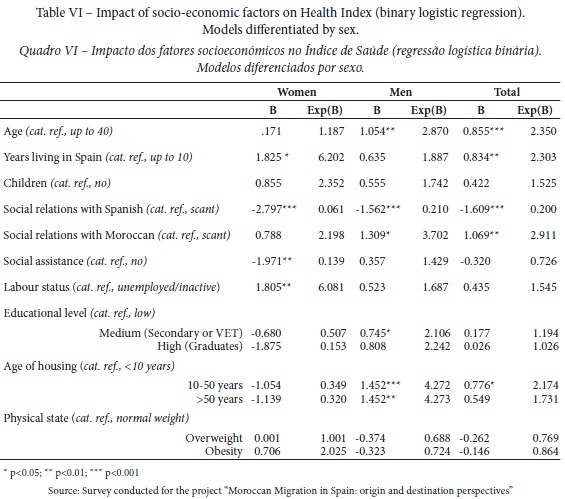

Next, table VI presents the models separated by sex of binary logistic regression employing all the independent variables in order to discover the probability that the Health Index is affected by themx.

Concerning variables related to time, the effect of age is statistically significant among men but not among women. When men have less than 40 years, it increases nearly three times the probability of perceiving that their health status has improved or stayed the same after the migration to Spain. Nevertheless, when looking at the results of years elapsed since migration, to have migrated less than 10 years ago has for women a statistically significant effect, but not for men. Women are in this case the ones to show a higher probability -of around of six times- of having the same or an improved perceived health status after migration to Spain.

What happens with regard to the variables associated with the field of social support? Generally speaking, social ties benefit health. When people have a greater overall involvement with formal (e.g., religious or social organizations) and informal (e.g., family, friends and relatives) social ties, their health benefits. This can be either because social ties can instill a sense of responsibility and concern for others or because relationships have emotionally sustaining qualities (Umberson & Montez, 2010). In the case of immigrants, they pass through a process of adjustment to the hosting society and an important transformation of their network of social relationships (Heering et al., 2004; Eve, 2010). In the migration experience, social support is a source of resources of a different nature that go beyond the network of social relationships (Ryan, 2011).

Social support resources provide affection (affective support), information in the search of employment and housing (emotional/informational support), access to basic social resources such as education and health and, instrumental assistance in language acquisition, obtaining documents, etc. (instrumental support). Also there are resources addressed to understanding and opportunities for social participation (positive social interaction support) (Hernández, Pozo, Alonso & Martos, 2005). When the level of social support is low, there is an emergence of health problems. Isolated people report poorer health, both physical and psychological. Hence, the importance of insisting on the development of public policies of social inclusion that include the sharing of resources of various types of social support that may come to have a positive impact on the health of immigrants (Rodríguez Álvarez et al., 2009; Salinero-Fort et al., 2011). On the other hand, it is important to remember that sex may affect migrants’ networking strategies. It has been pointed out that although women’s, especially mothers’, social networking strategies are different from men’s in the sense that they are more local and child oriented, can equally provide practical and emotional support (Heering et al., 2004; Ryan, 2007).

Using the information from the survey, this issue may be addressed with different variables associated with interpersonal and social relationships. Our idea was that people with a wide and diverse circle of social relationships – those who have children, interact with other Moroccan immigrants and with local people, non-Moroccan immigrants – are more likely to show a positive variation in terms of self-perceived health status than those who do not enjoy such social ties.

And, with respect to social support, there is the variable related to access to social services. It may be expected to have a positive impact on self-appraisal of health status evolution.

Thus, the variable of having children or not has been included in the logic that the immigrants who have children – even more so when the children are young – share everyday spaces with the rest of the population more frequently than those do not have children. This can help them develop contact and friendships with people in similar life situations, through meetings at school, the health centre, the playground, while shopping, etc. In short, it is more difficult to be isolated when taking care of a child. However, the multivariate analysis carried out by sex indicates that this variable is not relevant in the health status variation of Moroccan immigrants, be they women or men.

In the survey, two variables in which the Moroccan interviewees are asked about the kind of relationships they have are taken into consideration: on the one hand, with local people, and on the other hand, with other Moroccan immigrants. The possible answers enable an estimation of the support these people could receive and perceive from society.

The variable of “social relationships with local people” may be described as significant in both multivariate models. Both models also share the negative coefficient, which indicates that when these relationships are friendships, the health perception worsened with respect to the self-perception at the time of migration. Therefore, having a point of reference or comparison with local friends appears to have a negative impact on the assessment of how their health has evolved among the Moroccan interviewees. Nevertheless, this finding concerns a relationship-type of very limited statistical significance. In the case of women, their relationship with local friends hardly affects their health status variation at all, and likewise very little in the case of men. It is difficult to give an explanation for this result. Perhaps by maintaining closer relations with locals, the interviewees develop a more critical perception of their health status since they can incorporate a new vision about what is a disease or well-being.

A more pronounced difference can be found in the “social relationships with Moroccan immigrants” variable. In the female multivariate model, it has no significance, whereas in the male model it is statistically significant. Therefore, for men, the fact of having friendships with their fellow countrymen increases 3.7 times the probability of having an equal or better current self-perception of their health than before migration to Spain. It seems that among men having friends of the same origin gives them access to an important source of social support, that we can assume includes affective, emotional and informational support. An interesting question to research would be why it is not the case among women.

The only specific variable that tackles social support for the immigrant population included in our analysis is the access –or not- to some form of social assistance. It may be read as a proxy value for public support, external to the individual and their family, neighbourhood relations or any other everyday contact, typical of developed societies in general and of Navarran society in particular. The variety of measures (economic allowances, payment of bills, food, etc.), its orientation (some addressed to individuals, others to families), providers (both regional and national governments, diverse NGOs) together with the recent economic depression that has affected to many people –not only immigrants- helps us to understand that a high percentage of Moroccan immigrants (a 72% of the total interviewees) have received at least one of these measures.

In the male multivariate model, this variable is not statistically significant, whereas it is in the female model. The coefficient is negative, so it seems that receiving some sort of social support increases –although very slightly- the probability of having a worse self-perception of health than at the moment of migration. Maybe the fact of suffering from economic necessity in an environment that can be perceived as hostile even though the help received is behind this negative effect, contrary to what we could expect. And, again, a difference for which we do not have an explanation

Given the background of Moroccan as economic migrants, and the need to have sufficient resources to live in Spain, we thought that the factor of having a job (as compared with being unemployed or not to be looking for a job) was related to positive variation of the self-appraisal health status. Having financial resources provides security, and it seems logical that it reduces the risk of problems and illnesses associated with stress. Once again, the results evince a sharp contrast between the female and the male multivariate models. The employment situation has no statistical significance in the male model; in other words, it appears that having a job (or not) has no impact on the variation in perceived health status. Nevertheless, in the female model this is a positive and significant variable. When the Moroccan woman is in gainful employment the probability of showing a better or equal self-perceived health status than before migration is more than 6 times higher than when they do not work outside home or are unemployed.

According to the bibliography, having paid work in the host society implies not only a provision of income for the household but a way of obtaining a greater personal autonomy and of challenging the traditional Moroccan womens role of mother and wife (Martín Díaz, 2008). Working outside the home is a value in itself, a “quota of power” and prestige in their home environment, even when it is a job in domestic service or any other elementary occupation (Gregorio Gil & Ramírez Fernández, 2000; Monquid, 2004).

Educational level is another factor that we thought could have an effect on the self-perception of health and its variation. People with a higher educational level have a better ability to adapt and use more appropriate strategies to cope with problems, including a more efficient use of health and psychosocial services, and economic resources (Rodríguez Álvarez et al., 2009). Better-educated adults have been found to have engaged in more diverse personal networks (Umberson & Montez, 2010) and to be more receptive to preventive care (Carrasco-Garrido, Jiménez-García, Hernández-Barrera, López de Andrés, & Gil de Miguel, 2009). In our case study, to have a medium to a high level (secondary studies completed or higher) may be expected to function as a support element, on the one hand, in getting a job, and, on the other hand, in developing better social interaction skills.

In the female model, no statistical significance has been found, whereas in the male model it is statistically significant in the case of men with secondary studies. The coefficient is positive so it appears that men with secondary studies increase 2 times the probability of having an equal or better current self-perception of their health than before migration to Spain. This result points to a correlation with the health status variation as expected.

Our analysis includes a factor related to housing. The starting assumption was that it is an essential and defining element of quality of life, as well as being a major financial outlay for the immigrant population. In our case, a 74% of those interviewed live in a rented house and a 23.7% own the house in which they live. A previous descriptive analysis of several variables related to housing such as provision of hot water, electricity, bathroom, heating, kitchen, fridge, washing machine, television, etc., has proven to be scarcely discriminative: most of the housing had such basic services and electrical appliances. The variable “age of housing”, however, showed a wider variety of situations among Moroccan immigrants.

We use the “age of housing” as a proxy of the socio-economic level of the interviewee. Given that it is doubtful that she/he knows the real age of the housing, it can be assumed that she/he has subjectively assigned the age, probably based on the price of the property. Moroccan immigrants living in cities in Navarra inhabit mainly in working-class neighbourhoods and, when living in towns –the type of settlement common in the Ribera- they usually inhabit in the old part of the town, where are located the poorer and/or older houses. We can assume with little risk that the processes of gentrification have not yet reached these places.

The results show quite an interesting contrast between male and female. Among women, this variable does not seem to have any impact on the health index; but, among men, to live in a medium-age or old housing, which are presumably cheaper than new housing, raise more than 4 times the probability of positive or equal variation in health perception. That is to say, when housing expenses are lower, the comparison of the present health status in relation to the past improves or remains equal for men. Again this is a question with no clear explanation.

Regarding the physical condition of the interviewee, in addition to asking for the health status prior to migration to Spain and the present status, the survey collected data on stature, weight, smoking habits, and the effects of different illnesses.

The descriptive analysis of the different illnesses revealed a very low incidence among the interviewees, which precluded the need for more detailed analysis. Therefore, it would appear to be a population with a good health status according to objective parameters resulting from the selective factors typical of migration processes. That is to say, the so-called “healthy immigrant effect” (Nielsen & Krasnik, 2010; Villarroel & Artazcoz, 2012; Malmusi & Ortiz, 2014). However, the healthy immigrant effect might explain the relative health advantage of recent foreign immigrants (Malmusi et al., 2010) but in this case they are surveyed, as we already know, not so soon after their arrival in Spain (an average of 8 years for women and 14 years for men). This situation may also be due to the populations ignorance about their real health situation due to their reluctance to use medical services, unless it is strictly necessary. Carrasco-Garrido et al. (2009), found that the immigrant population shows values significantly lower than the native population in the frequency of medical visits and in the use of preventive health measures (such as the flu vaccination), whereas the frequency of accessing emergency services and traditional medicines is much higher. Rodríguez Álvarez et al. (2008), report similar results.

The BMI variable was used as a descriptor of the physical condition of the person who is overweight or perhaps even obese. Our logic points out that the individual with a weight alteration shows higher risks for his/her health and may experience greater constraints on his/her everyday life. In other words, his/her perception of his/her present health status may be more negative and, as a result, may impact negatively on the health index. Nonetheless, this variable is not significant in either of the multivariate models.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

This work carries out an analysis of the social determinants that affect the health status variation among immigrants of Moroccan origin resident in the Spanish region of Navarre in 2013. That immigrant sex is not included as an independent variable in the statistical model, but as specific models, separately, for women and men.

A dependent variable or health index relating to current self-reported health status and the interviewees self-perception just prior to migrating to Spain was constructed, and an analysis of binary logistic regression carried out. Among the social determinants introduced there are variables that relate to socio-demographic aspects such as having children or not, and the number of years resident in Spain; others concern social capital such as level of educational achievement and the intensity of social relationships with local people, on the one hand, and with Moroccan immigrants, on the other. The professional situation is also taken into account, receipt of social security assistance or not, the age of housing; and finally, physical condition, an objective indicator of health, which contrasts “normal” with being overweight or obese.

The results of the analysis reflect an interesting contrast with other studies carried out, as the women in our sample have a health status perception and a variation over time that is more positive than the results for men, because they are younger and have lived for a shorter time in Spain.

However, another possible explanation could be associated with the heterogeneity of our sample of interviewed women. There is an increased number of women that have been emigrating to Spain developing a trend of female-initiated immigration, instead of the traditional or female-chained immigration following a husband or with the whole family (Montoro-Gurich, 2014). These women, mainly divorced but also single, envisage the migration not only as a way of improving their economic situation but especially as a way of gain autonomy and independence from the social and familial links (Ouali, 2003; Moujoud, 2008; Ait Ben Lmadani, 2012). In our survey, we have women independent, “head of household”, who could be an example of this type of migration. In these cases, it could be logical to find a current self-perception of health equal or even better than prior to the migration, because they have chosen to migrate. On the other hand, there are also women that represent a much more conservative style of life. We cannot affirm that all the women not heading a household interviewed assume that their goal in life is “to marry, have children and provide a decent home for their working husbands” (Pham, 2012), but it seems plausible that among the important percentage of homemakers we have found the consistency of their situation with their traditional values could help to explain the females good health self-perception.

Furthermore, there are some marked disparities by sex in the regression models. Among females, the factor which increases more the probability of a positive perception on their health status evolution is gainful work outside the home. This reality can be both interpreted in economic terms and of increasing personal autonomy, obtained either because of necessity or negotiation on customs and values (Villarroel & Artazcoz, 2012). In the case of men and apart from being younger than 40 years, there are three significant variables: age of housing, which we have interpreted in terms of its economic cost, social relationships with other Moroccan and, having a medium level of education.

In other words, in the Moroccan population, whose defining characteristic is their status as economic migrants (Massey et al., 2011), the variables that influence a better health status may likewise be interpreted in economic terms. However, the differences found should be taken into account when designing social and preventive medical policies for this population. For instance, investing in social policies that aim to facilitate womens access to the labour market would have a twofold effect: improve their economic situation and, in the longer run, maintain a better health status. Similarly, in the case of men, a sensitive housing policy would have a greater effect on their health status than investing in current social benefit schemes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is part of the project entitled "Moroccan Migration in Spain: origin and destination perspectives", which began in November 2011 thanks to an agreement between the University of Navarra, Princeton University (Office of Population Research) and the Navarra Red Cross. It has received funds from the Government of Navarra (Calls Jerónimo de Ayanz 2011 and 2012) and the Fundación Universitaria de Navarra (FUNA, 2013 and 2014).

A preliminary version of this work was presented at the XI Congress of the Asociación de Demografía Histórica (ADEH), Cádiz, June 21th-24th 2016.

REFERENCES

Ait Ben Lmadani, F. (2012). Femmes et émigration marocaine. Entre invisibilisation et survisibilisation: pour une approche postcoloniale [Women and Moroccan emigration. Between invisibilisation and survisibilisation: for a postcolonial approach]. Hommes et migrations, 6(1300), 96-103. [ Links ]

Arango, J., & Martin, P. (2005). Best Practices to Manage Migration: Morocco-Spain. International Migration Review, 39, 258–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2005.tb00262.x [ Links ]

Arber, S. (1997). Comparing Inequalities in Womens and Mens Health: Britain in the 1990s. Social Science and Medicine, 446, 773-787. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00185-2 [ Links ]

Au, N., & Johnston, D. W. (2014). Self-assessed health: What does it mean and what does it hide? Social Science & Medicine, 121, 21-28. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.007 [ Links ]

Bhopal, R. S. (2012). Research agenda for tackling inequalities related to migration and ethnicity in Europe. Journal of Public Health (Oxf), 34(2), 167-173. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fds004 [ Links ]

Bhopal, R., & Rafnsson, S. (2012). Global inequalities in assessment of migrant and ethnic variations in health. Public Health, 126, 241-244. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.11.016 [ Links ]

Borrell, C., Muntaner, C., Solè, J., Artazcoz, L., Puigpinós, R., Benach, J… Noh, S. (2008). Immigration and self-reported health status by social class and gender: the importance of material deprivation, work organisation and household labour. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 62(e7). doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.055269

Carrasco-Garrido, P., Jiménez-García, R., Hernández Barrera, V., López de Andrés, A., & Gil de Miguel, Á. (2009). Significant Differences in the Use of Healthcare Resources of Native-Born and Foreign Born in Spain. BMC Public Health, 9, 201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-201 [ Links ]

Castañeda, H., Holmes, S. M., Madrigal, D. S., DeTrinidad Young, M. E., Beyeler, N… Quesada, J. (2015). Immigration as a Social Determinant of Health. Annual Review of Public Health, 36(1), 375-392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419

Cebolla-Boado, H., Requena, M., & Revenga, D. (2009). Los inmigrantes marroquíes en España [Moroccan immigrants in Spain]. In D. S. Reher & M. Requena (Eds.), Las múltiples caras de la emigración en España [The multiple faces of emigration in Spain] (pp. 251-287). Madrid: Alianza. [ Links ]

Constant, A., Garcia-Munoz, T., Neuman, S., & Neuman, T. (2014). Micro and Macro Determinants of Health: Older Immigrants in Europe. Paper presented at the 11th IZA Annual Migration Meeting, Bonn, May 30, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.iza.org/conference_files/amm2014/neuman_s175.pdf

Davies, A. A., Basten, A., & Frattini, C. (2009). Migration: a social determinant of the health of migrants. Eurohealth, 16(1), 10-12. [ Links ]

Estrategia Navarra para la Convivencia (2014). Diagnóstico: Contexto sociodemográfico [Diagnosis: Sociodemographic context]. Gobierno de Navarra, Departamento de Políticas Sociales. Retrieved from https://www.navarra.es/NR/exeres/6996BF92-2C71-4F42-8C4B-6F1FE2D500FB.htm [ Links ]

Eve, M. (2010). Integrating via networks: foreigners and others. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 33(7), 1231-1248. doi: 10.1080/01419871003624084 [ Links ]

Foets, M. (2011). Improving the quality of research into the health of migrant and ethnic groups. International Journal of Public Health, 56, 455-456. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0293-1 [ Links ]

Gazard, B., Frissa, S., Nellums, L., Hotopf, M., & Hatch, S. L. (2015). Challenges in researching migration status, health and health service use: an intersectional analysis of a South London community. Ethnicity & Health, 20(6), 564-593. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2014.961410 [ Links ]

Gregorio Gil, C., & Ramírez Fernández, Á. (2000). ¿Es España diferente…? Mujeres inmigrantes dominicanas y marroquíes [Is Spain different...? Dominican and Moroccan immigrant women]. Papers, 60, 257-273. doi: 10.5565/rev/papers/v60n0.1042

Heering, L., van der Erf, R., & van Wissen, L. (2004). The role of family networks and migration culture in the continuation of Moroccan emigration: a gender perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30(2), 323-337. doi: 10.1080/1369183042000200722 [ Links ]

Hernández, S., Pozo, C., Alonso, E., & Martos, M. J. (2005). Estructura y funciones del apoyo social en un colectivo de inmigrantes marroquíes [Structure and functions of social support in a group of Moroccan immigrants]. Anales de Psicología, 2, 304-315. [ Links ]

Hill, T. D., Angel, J. L., Balistreri, K. S., & Herrera, A. P. (2012). Immigrant Status and Cognitive Functioning in Late Life: An Examination of Gender Variations in the Healthy Immigrant Effect. Social Science & Medicine, 75(12), 2076-2084. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.005 [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (INEbase). (2018). INEbase. Demografía y Población. Cifras de población y censos demográficos. [INEbase. Demography and Population. Population figures and demographic censuses]. Retrieved from http://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176951&menu=resultados&idp=1254735572981 [ Links ]

Llácer, A., Zunzunegui, M. V., del Amo, J., Mazarrasa, L., & Bolumar, F. (2007). The contribution of a gender perspective to the understanding of migrants health. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 61, ii4-ii10. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.061770 [ Links ]

Malmusi, D., & Ortiz-Barreda, G. (2014). Desigualdades sociales en salud en poblaciones inmigradas en España. Revisión de la literatura [Social inequalities in health in immigrant populations in Spain. Review of the literature]. Revista Española de Salud Pública, 88(6), 687-701. doi: 10.4321/S1135-57272014000600003 [ Links ]

Malmusi, D., Borrell, C., & Benach, J. (2010). Migration-Related Health Inequalities: Showing the Complex Interactions between Gender, Social Class and Place of Origin. Social Science and Medicine, 71(9), 1610-1619. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.043 [ Links ]

Martín Díaz, E. (2008). El impacto de género en las migraciones de la globalización: mujeres, trabajos y relaciones interculturales [The impact of gender on the migrations of globalization: women, jobs and intercultural relations]. Scripta Nova, XII(270), 133. [ Links ]

Massey, D. S. (1987). The Ethnosurvey in Theory and Practice. International Migration Review, 21(4), 1498-1522. doi: 10.2307/2546522 [ Links ]

Massey, D. S., Connor, P., & Durand, J. (2011). Emigration from Two Labor Frontier Nations: A Comparison of Moroccans in Spain and Mexicans in the United States. Papers, 96(3), 781-803. doi: 10.5565/rev/papers/v96n3.262 [ Links ]

Monquid, S. (2004). Les femmes émigrés vecteurs de modernisation? Le rôle occulté des femmes émigrées dans le dévelopment du pays dorigine: le cas marocain [Women emigrants vectors of modernization? The hidden role of women emigrants in the development of the country of origin: the Moroccan case]. Revue Passerelles, 28, 59-68. [ Links ]

Montoro-Gurich, C. (2017). Marroquíes en España: un análisis por género de los determinantes de las migraciones familiares en Navarra [Moroccans in Spain: an analysis by gender of the determinant factors on family migration]. Estudios Geográficos, LXXVIII(283), 445-464. doi: 10.3989/estgeogr.201715 [ Links ]

Montoro-Gurich, C. (2014). Inmigrantes marroquíes en España: transformaciones recientes en los perfiles socio-demográficos [Moroccan immigrants in Spain: recent transformations in socio-demographic profiles]. In AA.VV. (Eds.), Emigración, identidad y países receptores [Emigration, identity and receiving countries] (pp. 31-49). Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch. [ Links ]

Montoro-Gurich, C., & López Hernández, D. (2013). Medir la intregración de los inmigrantes en España [Measure the integration of immigrants in Spain]. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 63, 203-223. doi: 10.21138/bage.1612 [ Links ]

Moujoud, N. (2008). Effects de la migration sur les femmes et sur les rapports sociaux de sexe. Au-delà des visions binaires [Effects of migration on women and on social relations by gender. Beyond the binary visions]. Les cahiers du CEDREF, 16, 56-79. [ Links ]

Nielsen, S. S., & Krasnik, A. (2010). Poorer Self-Perceived Health Among Migrants and Ethnic Minorities versus the Majority Population in Europe: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Public Health, 55, 357-371. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0145-4 [ Links ]

Oliva, J., & Perez, G. (2009). Inmigración y salud [Immigration and health]. Gaceta Sanitaria, 23(S.1), 1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2009.10.002 [ Links ]

Ouali, N. (2003). Les Marocaines en Europe: diversification des profils migratoires [Moroccan women in Europe: diversification of migration profiles]. Hommes et migrations, 1242, 71-82. doi: 10.3406/homig.2003.3975 [ Links ]

Pels, T., & de Haan, M. (2007). Socialization Practices of Moroccan Families after Migration: A Reconstruction in an Acculturative Arena. Young, 15(1), 71-89. doi: 10.1177/1103308807072690 [ Links ]

Pham, T. (2012). Maintaining Moroccan honor in Spain. In A. Biagni, G. Motta, A. Carteny & A. Vagnini (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Human and Social Sciences, 3, 16-20. [ Links ]

Phelan, J. C., Link, B. G., & Tehranifar, P. (2010). Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(S), S28–S40. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383498 [ Links ]

Pons Izquierdo, J. J. (2014). La comunidad marroquí en España: una propuesta metodológica para su cuantificación [The Moroccan community in Spain: a methodological proposal for its quantification]. In M. A. Sotés-Elizalde (Coord.), Emigración, identidad y países receptores [Emigration, identity and receiving countries] (pp. 51-71). Valencia: Tirant Humanidades. [ Links ]

Reher, D. S., & Requena, M. (Eds.) (2009). Las múltiples caras de la emigración en España [The multiple faces of emigration in Spain]. Alianza: Madrid. [ Links ]

Rodríguez Álvarez, E., Lanborena Elorduia, N., Erramib, M., Rodríguez Rodríguez, A., Pereda Riguerac, C… Moreno Márquez, G. (2009). Relación del estatus migratorio y del apoyo social con la calidad de vida de los marroquíes en el País Vasco [Relationship between migrant status and social support and quality of life in Moroccans in the Basque Country (Spain)]. Gaceta Sanitaria, 23(S.1), 29-37. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2009.07.005

Rodríguez Álvarez, E., Lamborena Elorduy, N., Senhaji, M., & Pereda Riguera, C. (2008). Variables sociodemográficas y estilos de vida como predictores de la autovaloración de la salud de los inmigrantes en el País Vasco [Sociodemographic variables and lifestyle as predictors of self-perceived health in immigrants in the Basque Country (Spain)].Gaceta sanitaria, 22(5), 404-412. doi: 10.1157/13126920 [ Links ]

Ronda, E., Ortiz-Barreda, G., Hernando, C., Vives-Cases, C., Gil-González, D., & Casabona, J. (2014). Características generales de los artículos originales incluidos en las revisiones bibliográficas sobre salud e inmigración en España [General Characteristics of the Original Articles Included in the Scoping Review on Health and Immigration in Spain]. Revista Española de Salud Pública, 88(6), 675-685. doi: 10.4321/S1135-57272014000600002 [ Links ]

Ryan, L. (2011). Migrants’ Social Networks and Weak Ties: Accessing Resources and Constructing Relationships Post-Migration. The Sociological Review, 59(4), 707-724. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2011.02030.x

Ryan, L. (2007). Migrant women, social networks and motherhood: the experiences of Irish nurses in Britain. Sociology, 41(2), 295–312. doi: 10.1177/0038038507074975 [ Links ]

Salih, R. (2001). Moroccan Migrant Women: Transnationalism, Nation-States, and Gender. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27(4), 655-671. doi: 10.1080/13691830120090430 [ Links ]

Salinero-Fort, M. Á., del Otero-Sanz, L., Martín-Madrazo, C., de Burgos-Lunar, C., Chico-Moraleja, R. M… Gómez-Campelo, P. (2011). The relationship between social support and self-reported health status in immigrants: an adjusted analysis in the Madrid Cross Sectional Study. BMC Family Practice, 12, 46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-46

Sen, G., & Östlin, P. (2007). Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient. Gender Inequity in Health: Why It Exists and How We Can Change It. Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/entity/social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/wgekn_final_report_07.pdf?ua=1

Solar, O., & Irwin, A. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health. Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). World Health Organization. Geneva. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_framework_action_05_07.pdf

Soriano Miras, R. M. (2008). Inmigrantes e identidad social: similitudes y diferencias en el proyecto migratorio de mexicanas a EEUU y mujeres marroquíes a España [Inmigration and social identity: similarities and differences in the migratory project of Mexican women to the U.S. and Moroccan women to Spain]. Migraciones, 23, 117-150. [ Links ]

Ullmann, S. H., Goldman, N., & Massey, D. S. (2011). Healthier Before They Migrate, Less Healthy When They Return? The Health of Returned Migrants in Mexico. Social Science and Medicine, 73(3), 421-428. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.037 [ Links ]

Umberson, D., & Montez, J. K. (2010). Social Relationships and Health: A Flashpoint for Health Policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(Suppl), S54–S66. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501 [ Links ]

Villarroel, N., & Artazcoz, L. (2012). Heterogeneous Patterns of Health Status Among Immigrants in Spain. Health and Place, 18(6), 1282-1291. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.09.009 [ Links ]

Williams, R. B. (1998). Lower Socioeconomic Status and Increased Mortality: Early Childhood Roots and the Potential for Successful Interventions. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 279(21), 1745-1746. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1745 [ Links ]

Recebido: janeiro 2018. Aceite: outubro 2018.

NOTAS

i The years of the figures have been chosen taking the year of maximum growth of immigration just before the economic crisis (2008), the year in which the survey was conducted (2013) and the latest figure available at the Spanish Statistics National Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística or INE) web page or INEbase (2017).

iiWe give the figures of the population born in Morocco living in Spain instead of the population of Moroccan nationality living in Spain because our survey was conducted to immigrants of Moroccan origin, independently of their current nationality.

iii The study received the approval of the University of Navarra Research Ethics Committee (Project reference 029/2010). The up-to-date version of the ethnosurvey can be consulted online at: mmp.opr.princeton.edu/research/questionnaire-es.aspx

iv The statistical program excluded from the binary logistic regression individuals with missing data, a total of 25 out of 257 interviewed (18 male and 7 female). The multivariate model finally included 232 cases, 158 male and 74 female.

v The formulation of this question was: “Currently, how is your health?” [Actualmente, ¿cómo es su salud?] and the possible answers were: very good [muy buena], good [buena], fair [regular], poor [mala]. The formulation to describe the health status prior to migration was: “Your health before coming to live to Spain was…” [Su estado de salud antes de irse a vivir a España era…] with the same possible answers.

vi In the interviewed population, there is a single case under normal values, and no one case of morbid obesity cases or BMI higher than 40.

vii The “recent health status” values, which strictly speaking, refer to such results, support the conclusion stated in the text. The women assert a “recent health status” better than the men. We ought to bear in mind that the answers are coded in ascending order (1= poor health, 2= fair, 3= good, 4= very good) and the mean of female distribution is 3.2, with a standard deviation of 0.8 against a mean in males of 2.8 and a standard deviation of 0.93.

viii Only 10% of women are aged between 46 and 64, while 30% of men are in this age-group.

ix Previous studies have shown that the typical profiles of Moroccan immigrant women, characterised as married women reunited with their husbands – sometimes after a long separation – have started to diversify and some single or divorced women who embark on the immigration on their own have begun to feature, albeit only rather faintly (Montoro, 2014). Moreover, we can confirm that the Moroccan immigrant regrouping process may run for between one and twenty years, although about 50% of the Moroccan male immigrants married and resident in Navarre have been joined by their spouses (and children, if they had them) within a six-year period (Montoro, 2017).

x The global fit testing (contrasts by Hosmer and Lemeshow) advocate the accurate specification of the proposed models.