Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.109 Lisboa dez. 2018

https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis12092

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Post-industrial urban areas in the context of ruination, demolition and urban regeneration in a post-socialist city: experiences of Lódz, Poland

Arruinamento, demolição e regeneração de áreas pós-industriais numa cidade pós-socialista: experiências de Lódz, Polónia

Ruine démolition et régénération urbaine dans une ville post-industrielle et post-socialiste européenne: le cas de Lódz en Pologne

Jaroslaw Kazimierczak1; Piotr Kosmowski2

1 Assistant Professor at Institute of Urban Geography and Tourism Studies, Urban Regeneration Laboratory, Faculty of Geographical Sciences, University of Lódz, 90-142 Lódz, Poland. E-mail: jaroslaw.kazimierczak@geo.uni.lodz.pl

2 Researcher at Urban Regeneration Laboratory, Institute of Urban Geography and Tourism Studies, Faculty of Geographical Sciences, University of Lódz, Lódz, Poland. E-mail: piotr.kosmowski@geo.uni.lodz.pl

ABSTRACT

Since the beginning of the 1990s Lódz has become one of the largest and the fastest shrinking cities in Poland and Central-Eastern Europe. This is the result of political transformation in Poland at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s, which caused the collapse of Lódz economy based on textile industry monoculture. The radical population change has triggered highly dynamic transformations in the urban fabric of Lódz and produced numerous ruins, voidances, unused houses and dwellings, abandoned and vacant land in a contemporary city, especially in its central, historical districts. Furthermore, one of the key roles in the process of ruination of Lódz’s 19th-century urban tissue was played by the communists who ruled the city without any respect to its urban heritage for almost 50 years from the end of World War II. That was an intentional and ideologically motivated policy. In contrast, new capitalist circumstances of urban development in Poland since political and economic transformation in 1989 have freed private property developers’ ”game of urban space” that has strengthened urban sprawl and decapitalization of historical, especially post-industrial buildings in Lódz downtown. The aim of our research is to identify qualities of post-industrial urban areas in the downtown of Lódz in the period of 1989-2016 and then the role of ruined and abandoned post-industrial buildings in the urban regeneration process.

Key words: Lódz; Poland; post-industrial urban areas; urban demolition; urban regeneration; urban shrinkage.

RESUMO

Desde o início dos anos 90 do século XX Lodz tornou-se uma das cidades de maior e mais rápido encolhimento na Polónia e na Europa Central e Oriental. Este foi o resultado de mudanças políticas que ocorreram na Polónia no final dos anos 80 e início dos 90, as quais levaram ao colapso económico de Lodz, uma cidade monoespecializada na indústria têxtil. Mudanças demográficas radicais resultaram em processos de transformação do tecido urbano de Lodz, levando ao surgimento de numerosas ruínas e terrenos vagos no espaço urbano, especialmente na parte central histórica da cidade. Além disso, um dos principais fatores de degradação moderna de edifícios do século XIX de Lodz foi a política consciente e intencional das autoridades comunistas, que geriram o espaço sem respeito pelo património material da cidade durante quase 50 anos, desde o fim da II Guerra Mundial. Novas condições para o desenvolvimento das cidades na Polónia, que sucederam depois da transição política e económica em 1989, geraram um novo "jogo pelo espaço", no qual o envolvimento do setor privado da construção reforçou o fenómeno da expansão urbana (suburbanização) e a descapitalização do tecido urbano histórico, em particular dos edifícios industriais. O objetivo de nossa pesquisa é identificar as qualidades das áreas industriais do centro de Lodz no período de 1989-2016 e o papel dos edifícios pós-industriais arruinados e abandonados no processo de revitalização.

Palavras-chave: Lodz; Polónia; áreas urbanas pós-industriais; demolição; revitalização; encolhimento urbano.

RÉSUMÉ

Depuis le début des années 1990, Lodz est devenue la ville rétécissante la plus grande et la plus rapide de Pologne et d’Europe centrale et de l’Est. Ce rétrécissement résulte des transitions politiques en Pologne au tournant des années 1980 et 1990 et de l’effondrement économique de Lodz fondée exclusivement sur l’industrie textile. Le changement de population a grandement influencé les dynamiques de transformation de la fabrique urbaine de Lodz, comme l’apparition de nombreuses ruines, de vacances d’exploitation de terrains et de logements, voire de bâtiments entiers principalement dans la partie centrale et historique de la ville. Par ailleurs, l’une des causes fondamentales de ruinification du tissu urbain datant du XIXe siècle à Lodz est la gestion intentionnelle et idéologique de la ville par les communistes sans considération aucune pour l’héritage urbain pendant près de 50 ans après la Seconde guerre mondiale. A l’inverse, les nouvelles circonstances capitalistes du développement de la Pologne depuis la transition économique et politique de 1989 ont libéré les processus spéculatifs de la vente des terrains urbains aux développeurs privés renforçant l’étalement urbain et la décapitalisation des bâtiments historiques, surtout post-industriels, du centre de Lodz. L’objectif de notre recherche est d’identifier la qualité des zones urbaines du centre de Lodz entre 1989 et 2016 et de définir le rôle des bâtiments post-industriels en ruine et abandonnés dans le processus de régénération urbaine.

Mots clés: Lodz; Pologne; zones urbaines post-industrielles; démolition; régénération urbaine; rétrécissement urbain.

I. INTRODUCTION

Urban regeneration consists in the multifaceted revitalisation of urban areas deprived of their economic, social and technical livelihoods. Although it focuses on areas of diverse origin and functions, it always aims at improving the quality of space (landscape) and utility, including the housing function. Regeneration is undertaken to increase the competitiveness of cities to attract new investment, residents, and tourists.

Post-communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) are lagging behind Western Europe on regeneration by several dozen years (Kaczmarek, 2003). In the second half of the 20th century, the growth of cities in Central and Eastern Europe was predominantly quantitative, based on intense industrialisation, increasing number of inhabitants and territorial expansion. Increases in population and investment in urban infrastructure and housing were smaller than the increase in investment in industry, which Kondrád and Szelény (1977) termed as “underurbanisation”. Communism artificially extended the presence of industry in the CEE cities, hence, the problem of idle and degraded post-industrial areas emerged in the 1990s after the systemic transformation. It was also the age of shortages of resources for urban infrastructure and housing. At that moment, post-communist cities in CEE faced economic downturn, depopulation, and spatial degradation. One of the cities the most tackled by the changes at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s is Lódz, the biggest textile centre in Poland and in Central and Eastern Europe, built on the 19th century industry and, although left untouched by the WWII, with housing stock deeply degraded over the years of communism. Due to radical changes and the collapse of the textile industry, post-industrial areas covered ca. 23% of the centre of Lódz.

This paper discusses characteristics of post-industrial areas located in central parts of Lódz paying special attention to spatial transformations in the years 1989-2015, as well as identifying and classifying post-industrial ruins as potential investment areas. Our starting point rests on the assumption according to which the quality of urban life is determined by the quality of buildings and public spaces in cities (Aiello, Ardone, & Scopelliti, 2010), as well as by the need to adjust urban space to current needs of residents and users (Klassen, 1988). Poor urban management in Lódz, in particular in the city centre, translates into low attractiveness of the city as a place to work, study, and live. By regenerating degraded post-industrial areas we may improve the quality of urban space in Lódz and, by the same token, stop and, at a later stage, reverse unfavourable demographic trends.

II. ORIGINS OF DEGRADATION AND RUINATION OF (POST-)SOCIALIST CITIES

Post-socialist cities are cities at the transition stage, characterized by dynamic processes of change rather than static patterns (Sýkora, 2009), where the communist state and market economy exhibit in a mixture of creative destruction and social transformation. According to Golubchikov (2017) this process is directly connected with changing meaning-making in relation to urban space. Political transformations, which took place in Poland and in other countries of CEE at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s triggered a series of negative outcomes of an economic, social, cultural, legal, and spatial nature. Depopulation (Kabisch, Haase, & Haase, 2012) and spatial degradation (Marcinczak & Ogrodowczyk, 2014) are at the top as consequences of this multi-faceted crisis in post-socialist cities in Europe. Ziobrowski and Domanski (2010) estimated that 120 000ha, that is 22% of urban areas in Polish cities, are run-down and need to be revitalized immediately. Among them, 52% are historic downtowns and 12% are post-war housing estates dominated by blocks of flats. It means that 24% of Poles live nowadays in run-down areas in Polish cities. Although there is not enough evidence showing degradation of urban areas and poor living conditions as key determinants of urban shrinkage, there are numerous research projects in Europe that have indicated strong linkages between economic decline of the city and depopulation (Martinez-Fernandez, Audirac, Fol, & Cunningham-Sabot, 2012; Wiechmann & Bontje, 2015; Haase, Rink, & Grossmann 2016). Haase, Rink, Grossmann, Bernt, and Mykhnenko (2014) thoroughly examined the conceptual framework of urban depopulation based on theories that explain the substance of urban crisis in the second half of the 20th century and in the early 21st century. In their studies, they pay special attention to five concepts: stage or life-cycle theories of urban development, suburbanization, accumulation of capital and its spatial-temporal circulation, territorial divisions of labour, and second demographic transition. Specifically, post-communist cities have recorded drops in the population in middle-sized and big cities (usually with the exception of capital cities), while the number of inhabitants of big cities in Western Europe grows continuously (Turok & Mykhenko, 2008).

Haase et al. (2016), argue that the crisis of cities in the CEE region after 1990 stemmed mainly from the collapse of industry, unemployment and impoverishment of society, all of which were experienced the most painfully by industrial cities and their central areas in particular. In contrast to the cities of Western Europe, whose suburbs had regularly been exposed to urban renewal efforts since the 1970s, centres of post-communist cities are inhabited by elderly people, the most economically vulnerable, which Haase, Grossmann, and Steinführer (2012) demonstrated using the examples of Lódz and Brno in the Czech Republic. The modernization gap, promoting urban growth through building new housing areas at the peripheries of cities (Szafranska, 2014; Monclús & Díez Medina, 2016) together with the lack of economic and social capital over the communist era degraded central areas of cities. Nowadays, due to the poor technical condition of the housing stock, central areas of cities get depopulated also due to lifestyle changes, which stimulated urban-to-rural migrations, mostly to suburban areas, and finally urban sprawl of post-socialist cities (Cirtautas, 2013; Geshkov, 2015; packová, Dvorácková, & Tobrmanová, 2016). Among other depopulation factors in cities in the CEE region, Haase et al. (2016), point to neoliberal urban policy that promotes investors’ interests and at the same time neglects intensifying social problems. As a result, we witness state-led gentrification, which leads to social and economic segregation of central urban areas and exclusion; examples of such changes after 1990 can be traced, inter alia, in Bucharest, Romania (Marcinczak, Gentile, Rufat, & Chelcea, 2013) and Budapest, Hungary (Ladányi, 2002).

The recent research by Stryjakiewicz (2013) indicated that 52% of Polish cities over 5 000 inhabitants suffered a permanent or temporary population loss in the period of 1990-2010 as a result of socio-economic changes in the 1990s. Regarding larger Polish cities with a population exceeding 100 000, the share of demographic shrinkage achieved 69%. Among the most affected large cities in Poland a significant role is played by post-industrial cities, such as: Bytom, Chorzów, Katowice, Ruda Slaska, Sosnowiec (all at Silesia region), Walbrzych, and especially Lódz which is the largest city among all Polish shrinking cities, and one of the largest shrinking cities in Europe. The above mentioned cities are suffering the most from depopulation but, at the same time, their spatial degradation is the deepest. Three among them: Bytom, Walbrzych, and Lódz back in 2014 were considered regions requiring special government assistance in regeneration by the Ministry of Development of the Republic of Poland (the then Ministry of Infrastructure and Development).

Studies conducted by Ziobrowski and Domanski (2010) suggest that the crisis of cities in Poland links not only to the degradation of housing areas but also to gradual demolishing and ruining of their industrial heritage. As shown by research results, 20% of degraded spaces in Polish cities are post-industrial areas. Post-industrial urban areas are understood as those on which industrial activity was discontinued (Novy & Peters, 2013), often, but not always associated with processes of de- and reterritorialization (Sassen, 2001). Such areas may be also referred to as the post-industrial urban fallow, using the analogy to the stages formulated in Conzen’s theory (Kaczmarek, 2003). They are barriers to urban development meaning they must be brought back to life for smooth performance of cities as coherent spatial and functional systems. Simultaneously, post-industrial areas in cities should be interpreted as valid urban capital because they act as development reserve, in accordance with sustainable growth principle and the idea of a compact city (Roberts & Sykes, 2008). Post-industrial areas represent high investment potential as possible locations of institutions of 3rd and 4th sectors (referred to as metropolitan institutions) because, inter alia, of their location in the city landscape and cultural values of preserved post-industrial buildings. The size of post-industrial areas, which naturally predestines them for performing metropolitan functions and their compactness helpful in shaping a new morphological and functional unit. The above listed qualities make post-industrial areas highly susceptible to regeneration as evidenced in studies conducted by Kaczmarek and Kaczmarek (2010) in Lódz. Preservation of local culture and identity of cities is an important aspect for their global race for new investments, residents, and tourists (Yeoh, 2003). Regeneration of post-industrial areas, decisive for the attractiveness of post-industrial cities, makes part of this approach.

III. STUDY AREA, MATERIALS AND METHODS

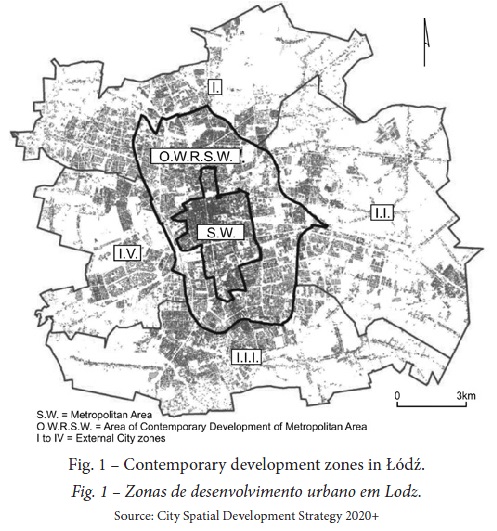

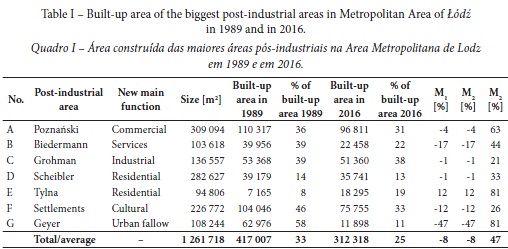

The study area is the so-called Metropolitan Area, the oldest part of Lódz downtown and the principal area of the current urban regeneration process in Lódz (fig. 1). It covers 14.2km2 which is 4.8% of the total area of the city. Based on Kazimierczak (2014a) we identified 174 post-industrial estates in the Metropolitan Area. Their average size is 1.8ha. For further detailed analysis we selected post-industrial areas bigger than 7.5ha. There are 7 of them representing 8.9% of the Metropolitan Area. They were established by the biggest industrial tycoons in the city who in the 19th century built textile factories.

The study was conducted based on bird’s eye view photographs taken between 1989 and 2016, we also used data from the Lódz Geodesy Centre [Lódzki Osrodek Geodezyjny] (thematic map of monuments). Data were processed using the ArcGis 10.2 software.

To assess the degree of transformation we use the following three measures:

M1 – difference in the share of total built-up between the years 2016 and 1989;

M2 – the share of the area covered by demolished buildings over the period 1989-2016 compared to total built-up area in 1989;

M3 – the share of new buildings built between 1989-2016 compared to the total built-up area in 2016.

IV. URBAN REGENERATION OF POST-INDUSTRIAL AREAS IN POST-SOCIALIST LÓDZ: A CASE STUDY

1. Brief approach to the case study

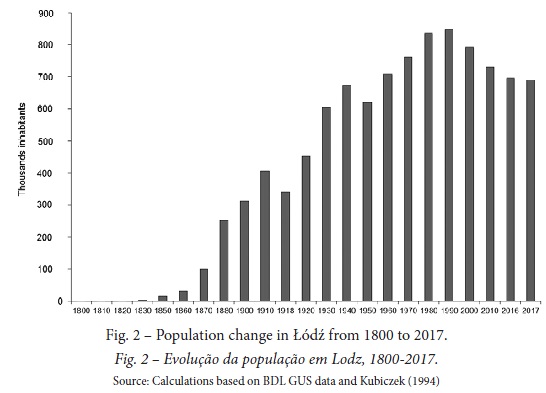

Population-wise, Lódz is the third city in Poland (693 797 residents in August 2017) and since the collapse of the textile industry at the beginning of the 1990s it has been struggling with a variety of economic and social problems. The crisis from which the city is still suffering can be observed in its permanent depopulation caused primarily by a negative birth rate, a negative migration balance and an aging society. Other reasons for its shrinking population include high mortality of people aged 20-60 resulting from poor health of residents, their low health awareness and unhealthy lifestyles. Over the period 1988-2017, the population of Lódz dropped by 19% (fig. 2). Within the same period, the population in the central district dropped by 27%, while in outer urban zones it increased by 9%. One of the reasons, but at the same time the effect, of such a dynamic depopulation of Lódz is the degradation of the material structure of the city, in particular of its central district (Marcinczak & Ogrodowczyk, 2014). The latest data from the National Census of 2002 show that 26.6% of residential structures in Lódz were built before 1944 (at that time the average for Poland was 21.7%) out of which 65% were located in the central district the city. Fifty percent of flats in these houses had no central heating installed, 30% were not connected to the sewage system and 12% had no toilets. According to Aiello et al. (2010), satisfaction with housing conditions is a major element in the assessment of the quality of living in a city and dissatisfaction may encourage emigration decisions. Thus, increased population in Lódz’s outer zones was due to intra-urban suburbanization and the presence of large housing estates originating from the communist times where the standard of flats was higher than in the central district (Szafranska, 2016). Recent surveys in post-socialist cities in CEE confirm the relatively high attractiveness of blocks of flats compared to decapitalised dwelling stock in city centres despite advancing regeneration (Tsenkova, 2000; Maier, 2005).

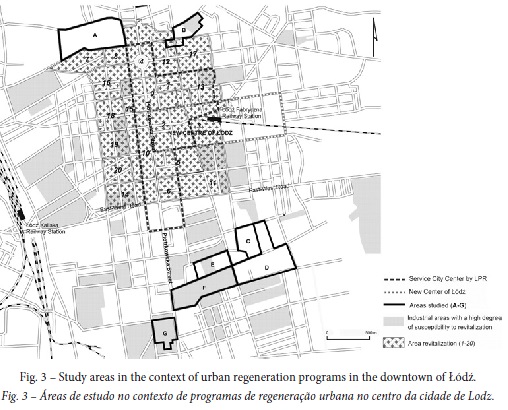

Studies in urban development conducted by the departments of the Lódz City Hall to draft the City Spatial Development Strategy until 2020+ and regeneration programmes of the city for the years 2007-2013 (Lódz Local Regeneration Programme .) and 2014-2020 (Lódz Municipal Regeneration Programme .) revealed that degraded areas in Lódz cover as much as 725ha. It is 2.4% of the overall city area within administrative borders and 5.2% of urban built-up areas. All of the degraded area is located in the historic centre of Lódz. Moreover, analyses showed that 75% buildings located in this area are in poor or very poor technical condition, 55% need modernising while 20% are ruined and should be demolished. The area of planned regeneration includes 1 783ha and occupies 6.1% of the city. It also fully includes the Metropolitan Area overlapping the area with the oldest buildings in Lódz (fig. 1). For the sake of comparison, a degraded area in the southern part of Manchester city centre where regeneration was carried out in the years 1988-1996 extended across 165ha, i.e. 0.014% of the city (Kazimierczak, 2014a).

2. Characteristics of post-industrial urban areas in Lódz in post-socialist era

After 1989 CEE countries experienced a triple transition: from communism to capitalism, from a centrally planned to a free market economy, and from relative autarky of communist countries, which cooperated amongst themselves to the need for a competitive positioning in the global economic system. According to Tsenkova (2008) this triple change fuelled transformations with implications in spatial arrangements linked with economic and social evolution and changes in urban management systems, including spatial and urban planning. New rules of land management and the emergence of real estate markets, non-existent in the times of communism, surely were important developments. Investment in real estate was connected with selective modernisation of cities and gentrification of internal districts. Post-industrial areas were also transformed. In circumstances of unregulated ownership relationships in housing and multi-functional areas in centres of post-industrial cities in the CEE (Marcinczak & Sagan, 2011), post-industrial areas favourably located, uninhabited and not occupied, became attractive investment plots. As observed by Musterd (2006) and Montgomery (2004), urban regeneration, which considers cultural and historic heritage as much as economic aspects, is a vital component of competitiveness of cities as confirmed by the examples of, amongst others, Manchester, Glasgow, Rotterdam, Antwerp, Pittsburgh, Chicago, and Melbourne. Adapted to new functions, the post-industrial heritage of cities produces specific genius loci (Hansen & Verkaaik, 2009) that attracts people to art galleries, restaurants, shops, universities, etc. The same factor also dictates the attractiveness of regenerated post-industrial premises transformed into apartments, especially when they are situated near the city centre. Many contemporary researchers stress rapid gentrification of central districts after a period of demographic collapse in the second half of the 20th century, both in Western Europe (Mykhenko & Turok, 2008) and in the CEE (Steinführer, Haase, & Grabkowska, 2011). It is the effect of fashion, changes in the lifestyle but also of the wish to walk to work (the idea of walkable cities, Leinberger, 2009), as well as to culture and entertainment facilities. The tendency is exploited by developers and is part of regeneration projects. It has got its dark side as well, i.e., secondary reproduction of inequality addressed by Sassen (2009).

Lódz has got a strong regeneration potential in its downtown area resulting from the presence of favourably situated, uninhabited and unused (idle) post-industrial plots. Post-industrial legacy improves the competitiveness of Lódz not only in Poland but also in Europe. In 2013, ca. 23% of the Metropolitan Area of Lódz was covered with historic post-industrial facilities representing the highest value. Some of them are protected by law as monuments. Despite that, since the beginning of the 1990s their degradation continued at an accelerated pace, which, in many cases, has led to their demolishing, legal and illegal. Buildings in this part of the city were demolished not only by private owners of post-industrial buildings guided by potential profits from land who abused the lack of their effective legal protection in the times of transformation but also as part of investment projects and regeneration of degraded areas (Kazimierczak & Kosmowski, 2017). Estimates show that since the beginning of the 1990s ca. 50% of historic industrial buildings located on private land in Lódz were demolished. One of the major tasks facing urban authorities is proper management of urban space, in particular public space in cities, which hosts cultural heritage accumulated for ages. Old industrial buildings are the strongest determinants of contemporary identity of the inhabitants of Lódz. For that reason they should be especially protected and consistently regenerated to preserve most of the material heritage of the industrial age, which gave shape to contemporary Lódz.

This paper examines spatial transformations that have taken place in 7 of the biggest 19th-century post-industrial areas (bigger than 7.5ha) in Lódz covering 8.9% of the Metropolitan Area. Besides, these areas are densely built-up and represent an unusual historic value since they were initiated by the major industrialists of the city engaged in multi-aspect growth of Lódz in the 19th and in the early 20th centuries. Their investment attractiveness, however, lies in very favourable location in the urban system, where they surround the historic core of the city with Piotrkowska street, a specific, linear city centre (fig. 3).

Studies in spatial transformations conducted for 7 of the biggest industrial estates in the Metropolitan Area of Lódz and the nature of investment activities helped us identify three different approaches to historic industrial buildings. The first one consists in demolition, often illegal and pursued against regulations which extend protection over such structures. Its goal was to keep the area while waiting for profitable proposals to develop or sell it in the future; demolition of post-industrial ruins was supposed to “prepare” land for future investment. The second identified approach consists of planned restoration, however, in connection with demolition of historic tissue. It can be observed in areas where over the period 1989-2016 more than 50% of buildings were demolished. In accordance with the classification proposed by Kazimierczak (2014b) this kind of regeneration is radical, while Jones and Evans (2009) call it tabula-rasa development. Last among the approaches is adaptation regeneration (Kazimierczak, 2014b), which preserves more than 50% of historic buildings and adapts the structures, often ruined, to new functions (table I).

Post-industrial areas in the Metropolitan Area of Lódz experienced different development patterns in the period 1989-2016, despite similarities with respect to factors, such as their size, compactness and preservation of post-industrial premises, which are decisive conditions for the potential location of metropolitan functions and susceptibility to regeneration depending on favourable urban planning circumstances surrounding a particular location (Kaczmarek & Kaczmarek, 2010). Areas covered by the study differed when it comes to the intensity of preserved post-industrial structures. Transformations started with areas representing the lowest intensity of structures (post-industrial estates in Tylna, and the ones owned by Scheibler, Grohman, and Poznanski), where investment projects were not restricted by heritage protection regulations. Although these areas were rather loosely covered with post-industrial premises, everywhere demolition was a powerful regeneration tool. The scope of demolition was diverse and we may say that the industrial estate of Israel Poznanski (where in 2000-2006 a shopping, cultural and entertainment centre Manufaktura was established) and the one in Tylna (new residential area) underwent radical regeneration, while estates previously owned by Grohman (new industrial use) and Scheibler (residential and services area) experienced adaptation-type regeneration. When regeneration started, all of them were more or less degraded to the same extent. The technical shape of post-industrial infrastructure was irrelevant for the scope of demolition. Neither can we conclude that the new functional programme determined demolitions because, e.g., although both the eastern part of the Scheibler estate and the post-industrial area in Tylna were transformed into residential areas, each underwent a different type of regeneration (adaptation and radical). In both areas the share of post-industrial structures was relatively low (8% and 14%, respectively). The type of regeneration depended on functions planned for these areas: industrial in Grohman estate and services in Manufaktura. As shown by studies, preservation and usefulness of post-industrial premises were higher in Grohman estate where industrial function was maintained.

The other three examined post-industrial estates (of Biedermann, Geyer and the western part of the Scheibler post-industrial area so called Posiadla wodno-fabryczne, with the exception of Art_Incubator – a new area of offices, galleries, conference and exhibition rooms) did not experience planned transformations over the years 1989-2016. The preservation rate of historic factory premises in these areas is equally differentiated as in already regenerated areas and ranges from 19% to 74% compared to 1989. However, the absence of repair efforts over the 27 years following the collapse of the textile industry in these territories deepened the degradation of the existing facilities, which are mostly ruined. Having examined regeneration projects in four other studied areas we cannot unambiguously conclude that the presence of post-industrial ruins exerts a positive or negative impact upon further investment projects, types of implemented functional programmes and the degree of utilisation of post-industrial structures that have survived. It means it is decided by way of a compromise between the investor and institutions which take care of material heritage.

Post-industrial areas within the Metropolitan Area of Lódz exhibit two features. Firstly, all of them can be found in the peripheries of the historic city centre, which is why they cover a substantial chunk of space attractive for hosting metropolitan functions. Structure intensity in post-industrial estates is lower than that in plots in the city centre, making investment easier. Monuments may pose challenges but, as demonstrated by our analysis, the fact that these buildings are historic, and in most cases degraded, did not impede their demolition. These areas manifested big potential for spatial transformations confirmed by a high share of new structures, on average 31% in 2016 with the estate in Tylna reaching as much as 93% and 61% in Manufaktura. The second specificity consists of the peripheral location of these areas south of the Metropolitan Area vis-à-vis currently implemented regeneration projects in the city centre linked with the development of the New Centre of Lódz [Nowe Centrum Lodzi] (fig. 3). The factor may have serious implications for investment attractiveness of these areas, their further stagnation (even though for some of them development plans have been drafted), and further decapitalisation of surviving post-industrial premises. No doubt, regeneration efforts in post-industrial areas covered by the study may positively impact the image of historic city centre in the eyes of investors and (potential) residents and slow down the depopulation of the city centre with the potential to stop, in a longer time perspective, or even reverse unfavourable demographic trends.

3. Ruined post-industrial urban areas in the context of urban regeneration in Lódz downtown

Six out of seven the biggest compact post-industrial estates in the Metropolitan Area of Lódz are located within the degraded area specified in the Lódz Municipal Regeneration Programme 2026+. The only exception is the former industrial estate of Israel Poznanski, where Manufaktura was established (fig. 3). We need to note that the peripheral location of the analysed post-industrial areas in the Metropolitan Area excluded them from 2 pilot regeneration projects in 2007-2013 (Lódz Local Regeneration Programme 2007-2013) and 8 regeneration priority projects including 3 pilot projects for 2014-2020 (Lódz Municipal ) (fig. 3). On top of that, none of the examined post-industrial areas has been part of the remaining historic core of the city covered with regeneration in the period 2014-2020, which will be regenerated after the first 8 regeneration projects will have been completed. Potential scope of regeneration covers only the former Biedermann industrial estate. In the context of regeneration planned in the Metropolitan Area, this estate has probably got the biggest regeneration potential, in particular its northern part, which so far has not been used. Its attractiveness is enhanced by the vicinity of the regenerated city centre and its closeness to Piotrkowska street, the most prominent and real city centre original for its atypical linear shape (fig. 3). Other factors that impact the potential investment attractiveness of the Biedermann estate include immediate proximity of a park (located in the north-east and in the west) and the bus station (in the north). Potential investors should also appreciate the big area and partly preserved post-industrial premises (44% of the built-up area in 1989), which are currently ruined but represent high historic value. The neighbourhood of Manufaktura may also be an advantage as the shopping centre generates a lot of traffic in the city. The former Israel Poznanski estate was regenerated and transformed into Manufaktura precisely because its area was big enough and it was conveniently located in urban space near the main street of Piotrkowska. Its post-industrial premises were degraded and although some buildings enjoyed legal protection as monuments, they were demolished. The rest, i.e. only 37% of industrial facilities which were here in 1989, of high historic value were adapted to new urban functions.

The urban planning context of the rest of the analysed post-industrial areas in the southern part of the Metropolitan Area is utterly different. The distribution of previously and currently carried out regeneration projects demonstrates clear marginalisation of central city areas south of the East-West route. The East-West route was built in the 1960s and 1970s following a series of demolitions in the city centre. Nowadays, even though it has been partly channelled through a tunnel built in 2013-2015 it remains a clear spatial and functional barrier that cuts the historically shaped city centre (Metropolitan Area) together with Piotrkowska. The division revealed a clear dissonance when it comes to, e.g., public investment projects which favour the north part of the city centre considered the development core of the city. The same policy is pursued through public initiatives connected with regeneration, which since the 1990s have been focused on areas in the proximity of the northern part of Piotrkowska. Their objective was social and economic regeneration and they covered initiatives to improve the quality of public space and housing conditions.

It reduces investment attractiveness of examined post-industrial areas, despite their size, vicinity of Piotrkowska and big, spatially compact campus of the Lódz University of Technology (which also occupies post-industrial areas). Out of the examined areas in the south of the Metropolitan Area in Lódz, the eastern part of Scheibler’s industrial estate was the first to undergo spatial and functional transformations. It is located the furthest from Piotrkowska (among the examined lot) but, similarly to the Poznanski factory (Manufaktura), it represents high historic value to city residents. The Scheibler family created the biggest industrial empire in Lódz and Ksiezy Mlyn [Priest’s Mill] – a district built for the workers of Scheibler’s factories with its spatial layout unique in all of Central and Eastern Europe is the most valuable monument from the 19th century. Thus, we may assume that monumental buildings, even if ruined, together with the substantial area were decisive for its adaptation to new functions and the preservation of as much as 67% of its buildings from 1989. In areas covered by the study, post-industrial premises survived to the highest degree only in Grohman estate (79%) adapted to new manufacturing functions and in the western part of the Scheibler family industrial estate (74%), which is mostly ruined. Part of the latter is post-industrial idle land, similarly to the Biedermann post-industrial area in the north of the Metropolitan Area, which largely facilitates investment operations. Its historic structures, available land together with the compactness and size of the area make it one of the two top potential investment locations in the south of the city centre. The second one is the former industrial estate of Gayer located in the immediate neighbourhood of Piotrkowska. However, in the years 1989-2016 the area was radically transformed and 81% of facilities were demolished (illegally by a private owner). The new owner announced that he will use it for offices, services and residential purposes and 19% of the remaining post-industrial buildings will become part of the new spatial project, the so called Geyer’s Gardens. How fast post-industrial idle land can be transformed could be seen in post-industrial estate in Tylna (where 81% of premises were demolished in the years 1989-2016), where some construction development companies quickly erected a new housing estate.

Regeneration projects that have been delivered so far and investments planned in the Geyer estate testify to the attractiveness of introducing the housing function into post-industrial estates in the south of the Metropolitan Area. That is surely the result of their peripheral location in relation to the city centre developed in the north of the East-West route. Marginalisation of this section of the city centre and of post-industrial areas as a potential area for developing future metropolitan functions of the city is reinforced by a huge-scale city planning project titled the New Centre of Lódz located alongside the former railway track and the main railway and bus station – Lódz Fabryczna.

V. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

After 1990 post-communist cities in CEE countries found themselves in double trouble when their peripheral location (Michalska-Zyla, 2010) combined with the collapse in the industrial output, which, in turn, under the economic and social crisis, produced depopulation and physical degradation, especially in historic central areas. Post-industrial cities carried the additional burden of post-industrial areas. On the one hand, they were difficult cultural legacy that required protection but no funds were available to maintain them as there were other more urgent public expenses of the transformation period. On the other hand, post-industrial areas created opportunities of being involved into competitive positioning in a global economic system and compete for new investment, inhabitants, and tourists (Yeoh, 2003; Musterd, 2006) by shaping their specific genius loci (Hansen & Verkaaik, 2009). The notion of quality of place features increasingly more prominent in discussions on the competitiveness of cities and regions (Servillo, Atkinson, & Russo, 2011), which is why degraded urban areas are now being regenerated. The aim is not just social and economic recovery but often, primarily, the improvement of the housing stock, streets, parks and other constituents that shape broadly understood public space. In post-communist cities in the CEE region, such an approach has led to the “gentrification of facades”, i.e., to the restoration of facades in buildings (whose ownership situation is unquestionable) situated in prestigious districts while other buildings were left to their fate (Marcinczak & Sagan, 2011). Cities of the former GDR are exceptions in the region as their central districts got thoroughly regenerated. The case of Lódz demonstrates how difficult it is to include post-industrial areas into the regeneration exercise. Although post-industrial areas in Lódz represented spatial features that favour regeneration and adaptation to new functions (large spaces, good location, historically valuable buildings, and idle areas around that could be used) their potential remained untapped by regeneration. A significant portion of post-industrial premises which became privately owned after the systemic transformation got degraded, ruined and purposefully demolished. Regeneration projects run by public authorities further reduced the material legacy of the industrial age. Thus, Lódz is gradually losing its industrial identity and, by the same token, deprives itself of an element vital in competing for new investments, inhabitants and tourists.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This paper is financed by the National Centre for Science, Poland based on decision no. DEC-2014/15/B/HS4/01940.

REFERENCES

Aiello, A., Ardone, R., & Scopelliti, M. (2010). Neighbourhood planning improvement: Physical attributes, cognitive and affective evaluation and activities in two neighbourhoods in Rome. Evaluation and Program Planning, 33(3), 264-275. [ Links ]

BDL BUS: Bank Danych Lokalnych GUS [Local Data Bank]. [ Links ]

Cirtautas, M. (2013). Urban Sprawl of Major Cities in the Baltic States. Architecture and Planning, 7, 72-79. [ Links ]

Geshkov, M. (2015). Urban Sprawl in Eastern Europe. The Sofia City Example. Economic Alternatives, 2, 101-116. [ Links ]

Gminnym Programie Rewitalizacji Lodzi 2026+ [Lódz Municipal Regeneration Programme 2026+], Lódz: Lódz City Cuncil. [ Links ]

Golubchikov, O. (2017). The post-socialist city: insights from the spaces of radical societal change. In J. R. Short (Ed.), A Research Agenda for Cities (pp. 266-280). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [ Links ]

Hansen, T. B., & Verkaaik, O. (2009). Introduction – Urban Charisma. On Everyday Mythologies in the City. Critique Antropology, 29(1), 5-26. [ Links ]

Haase, A., Grossmann, K., & Steinführer, K. (2012). Transitory Urbanites: New Actors of Residential Change in Polish and Czech Inner Cities. Cities, 29(5), 318-326. [ Links ]

Haase, A., Rink, D., & Grossmann, K. (2016). Shrinking cities in post-socialist Europe: what can we learn from their analysis for theory building today? Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 98(4), 305-319. [ Links ]

Haase, A., Rink, D., Grossmann, K., Bernt, M., & Mykhnenko, V. (2014). The Concept of Urban Shrinkage. Environment Planning, 46(7), 1519-1534. [ Links ]

Jones, P., & Evans, J. (2009). Urban Regeneration in the UK. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Kabisch, N., Haase, D., & Haase, A. (2012). Urban population development in Europe 1991–2008 – the examples of Poland and the UK. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 36(6), 1326-1348. [ Links ]

Kaczmarek, S. (2003). Post-industrial Areas in Modern Cities. Bulletin of Geography, 2, 39-46. [ Links ]

Kaczmarek, S., & Kaczmarek, J. (2010). Tereny poprzemyslowe w Lodzi jako element potencjalu miasta [Post-industrial urban areas in Lódz as an element of the city's potential]. In T. Markowski, S. Kaczmarek & J. Olenderek (Eds.), Rewitalizacja trenów poprzemyslowych Lodzi [Revitalization of post-industrial areas in Lódz] (pp. 68-79). Warszawa: Biuletyn KPZK PAN, Tom CXXXII. [ Links ]

Kazimierczak, J. (2014a) Wplyw rewitalizacji terenów poprzemyslowych na organizacje przestrzeni centralnej w Manchesterze, Lyonie i Lodzi [Revitalization of post-industrial urban areas and its impact in organization of central space in Manchester, Lyon and Lódz]. Lódz: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Lódzkiego.

Kazimierczak, J. (2014b). Ksztaltowanie przestrzeni publicznej miasta w kontekscie rewitalizacji terenów poprzemyslowych w Manchesterze, Lyonie i Lodzi [Public space transitions in city centre and revitalization of post-industrial urban areas in Manchester, Lyon and Lódz]. Studia Miejskie, 16, 115-128. [ Links ]

Kazimierczak, J., & Kosmowski, P. (2017). In the shadow of urban regeneration megaproject: Urban transitions of downtown in Lódz, Poland. Urban Development Issues, 56(4), 39-50. [ Links ]

Klassen, L. H. (1988). Economical Thought and Practice. Lódz: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Lódzkiego. [ Links ]

Kondrád, G., & Szelény, I. (1977). Social Conflicts of Under-urbanisation. In M. Harloe (Ed.), Captive Cities – Studies in the Political Economy of Cities and Regions (pp. 157-173). London: John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

Kubiczek, F. (1994). Historia Polski w liczbach. Ludnosc. Terytorium [History of Poland in numbers. Population. Territory]. Warszawa: Glówny Urzad Statystyczny. [ Links ]

Ladányi, J. (2002). Residential Segregation among Social and Ethnic Groups in Budapest during Post-communist Transition. In P. Marcouse & R. van Kempt (Eds.), Of State and Cities. The Partitioning of Urban Space (pp. 170-182). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Leinberger, C. (2009). The Option of Urbanism: Investing in a New American Dream. Washington: Island Press. [ Links ]

Lokalny Program Rewitalizacji Lodzi w latach 2007-2013 [Lódz Local Regeneration Programme in 2007-2013]. Lódz: Lódz City Cuncil. [ Links ]

Maier, K. (2005). Czech Housing Estates. Recent Changes and New Challenges. Geographia Polonica, 78(1), 39-52. [ Links ]

Marcinczak, S., & Ogrodowczyk, A. (2014). Lódz – od polskiego Manchesteru do polskiego Detroit? [Lódz - from Polish Manchester to Polich Detrit?]. In T. Stryjakiewicz (Ed.), Kurczenie sie miast w Europie Srodkowo-Wschodniej [Urban shrinkage in Central-Eastern Europe] (pp. 79-88). Poznan: Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe. [ Links ]

Marcinczak, S., & Sagan, I. (2011). The socio-spatial Restructuring of Lódz, Poland. Urban Studies, 48(9), 1789-1809. [ Links ]

Marcinczak, S., Gentile, M., Rufat, S., & Chelcea, L. (2013) Urban Geographies of Hesitant Transition: Tracing Socioeconomic Segregation in Post-Ceausescu Bucharest. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), 1399-1417. [ Links ]

Martinez-Fernandez, C., Audirac, I., Fol, S., & Cunningham-Sabot, E. (2012). Shrinking cities: urban challenges of globalization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 36, 213-225. [ Links ]

Michalska-Zyla, A. (2010). Psychospoleczne wiezi mieszkanców miasta. Studium na przykladzie Lodzi [Psychosocial ties of city residents. A study on the example of Lódz]. Lódz: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Lódzkiego. [ Links ]

Monclús, J., & Díez Medina, C. (2016). Modernist housing estates in European cities of the Western and Eastern Blocks. Planning Perspectives, 31(4), 533-562. [ Links ]

Montgomery, J. (2004). Cultural Quarters as Mechanism for Urban Regeneration. Part 2: A Review of Four Cultural Quarters in the UK, Ireland and Australia. Planning Practice & Research, 19(1), 3-31. [ Links ]

Musterd, S. (2006). Segregation, Urban Space and the Resurgent City. Urban Studies, 43(8), 1325-1340. [ Links ]

Novy, J., & Peters, D. (2013). Railway Megaprojects as Catalysts for the Re-Making of Post-Industrial Cities? The Case of Stuttgart 21 in Germany. In G. del Cerro Santamaría (Ed.), Urban megaprojects: a worldwide view (pp. 237-262). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

Roberts, P., & Sykes, H. (2008). Urban Regeneration. A handbook. Los Angeles, London, New Dehli, Singapure, Washinton DC: SAGE.

Sassen, S. (2009). Cities Today: A New Frontier for Major Developments. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 626(1), 53–71. [ Links ]

Sassen, S. (2001). The global city. New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Servillo, L., Atkinson, R., & Russo, A. P. (2011). Territorial Attractiveness in EU Urban and Spatial Policy: A Critical Review and Future Research Agenda. European and Regional Studies, 21, 349-365. [ Links ]

Steinführer, A., Haase, A., & Grabkowska, M. (2011). Households as Actors. I: Housing Career and Housing Arrangements. In A. Haase, A. Steinführer, S. Kabisch, K. Grossmann & R. Hall (Eds.), Residential Change and Demographic Challenge. The Inner City of East Central Europe in 21st Century (pp. 185-207). Farnham: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Strategia przestrzennego rozwoju Lodzi 2020+, zalacznik do uchwaly nr LV/1146/13 Rady Miejskiej w Lodzi z dnia 16 stycznia 2013 r. [City Spatial Development Strategy until 2020+], Lódz: Lódz City Cuncil. [ Links ]

Stryjakiewicz, T. (2013). The process of urban shrinkage and its consequences. Romanian Journal of Regional Science, 7 (Special Issue on New Urban World), 29-40. [ Links ]

packová, P., Dvorácková, N., & Tobrmanová, M. (2016). Residential satisfaction and intention to move: the case of Prague’s new suburbanities. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 98(4), 331-348.

Sýkora, L. (2009). Post-socialist cities. In R. Kitchin & N. Thrift (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (pp. 387–395). Oxford: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Szafranska, E. (2016). Residential attractiveness of the inner city of Lodz in the opinions of city inhabitants. Studia Regionalia, 45, 8-21. [ Links ]

Szafranska, E. (2014). Transformations of large housing estates in post-socialist city: the case of Lódz, Poland. Geographia Polonica, 87(1), 77-93. [ Links ]

Tsenkova, S. (2008). Managing Change: The Comeback of Post-socialist Cities. Urban Research and Practice, 1(3), 291-310. [ Links ]

Tsenkova, S. (2000). Housing in Transition and the Transition in Housing: Experiences of Central and Eastern Europe. Sofia: Kapital Reclama. [ Links ]

Turok, I., & Mykhnenko, V. (2008). East European Cities – Patterns of growth and decline, 1960-2005. International Planning Studies, 13(4), 311-342. [ Links ]

Wiechmann, T., & Bontje, M. (2015). Responding to tough times: Policy and planning strategies in shrinking cities. European Planning Studies, 23(1), 1-11. [ Links ]

Yeoh, B. S. A. (2003). Contesting Space in Colonial Singapure: Power Relations in the Urban Built Environment. Singapopre: Singapore University Press. [ Links ]

Ziobrowski, Z., & Domanski, B. (2010). Rewitalizacja miast polskich jako sposób zachowania dziedzictwa materialnego i duchowego oraz czynnik zrównowazonego rozwoju. Podsumowanie projektu [Revitalization of Polish cities as a way to preserve material and spiritual heritage and as a factor of sustainable development. Summary of the project]. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Rozwoju Miast w Krakowie. [ Links ]

Recebido: maio 2017. Aceite: agosto 2018.