Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.104 Lisboa abr. 2017

https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis6970

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Mobility and spatial planning in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area

Mobilidade e ordenamento do território na Área Metropolitana de Lisboa

Mobilite et planification spatiale dans Laire Metropolitaine de Lisbonne

Sofia Santos1

1Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (CIES-ISCTE-IUL), Edifício ISCTE, Av. das Forças Armadas, 1649-026 Lisboa. E-mail: sofia.santos@iscte.pt

ABSTRACT

Peoples daily mobility and commuting patterns are differentiated by sociodemographic features. It relates to place as structure (spatial organization) and to public policy (spatial planning). Between urban structure and peoples traveling behaviours, spatial public policy should be called to reduce social inequality and to promote more just territories. This concerns the process of planning as well as its outcomes. Accessibility and conflict are important questions to be approached in both. The paper examines the importance of social issues in the design of the Lisbon Metropolitan Areas (LMA) policies on mobility and spatial planning. It continues to be a peripheral matter, despite some change at the discursive level. We begin by discussing how spatial justice and social inequalities can be central to mobility and spatial planning. Secondly, the general European and national policy background is presented. Finally, some fundamental trends of LMA mobility statistics are outlined followed by a critical reading of municipal and supramunicipal mobility related policies.

Keywords: Mobility; inequality; spatial planning; Lisbon Metropolitan Area.

RESUMO

A mobilidade e os movimentos pendulares são temáticas diferenciadas a partir das características sociodemográficas, na medida em que relaciona o espaço, quer enquanto estrutura (organização social), quer como um conjunto de políticas públicas espaciais (ordenamento do território). Desta forma, entre a estrutura urbana e o comportamento de mobilidade das pessoas, as políticas públicas espaciais são chamadas a intervir de forma a reduzir desequilíbrios sociais e a promover a justiça territorial, ou seja estamos a falar do exercício de planeamento territorial. A acessibilidade e os conflitos são questões importantes a serem abordados em ambos. O artigo analisa a importância das questões sociais nas políticas de planeamento e ordenamento do território e mobilidade, com enfoque na Área Metropolitana de Lisboa (AML) e demonstra que o tema prevalece como uma questão periférica, apesar de alguma mudança no campo discursivo. Começamos por discutir como a justiça espacial e as desigualdades sociais são fundamentais para a mobilidade e o ordenamento do território. De seguida revemos o plano de fundo da política europeia e nacional em geral. Finalmente apresentamos algumas tendências acerca da mobilidade na AML, com base em análises estatísticas e na leitura crítica das políticas municipais e supramunicipais da mobilidade na AML.

Palavras-chave: Mobilidade; desigualdade; planeamento e ordenamento do território; Área Metropolitana de Lisboa.

RÉSUMÉ

Les déplacements pendulaires des populations urbaines dépendent de leurs caractères sociodémographiques par rapport à lespace, cest à dire tant de leur organisation sociale que de la planification territoriale. Laménagement spatial doit intervenir pour réduire les déséquilibres sociaux et pour accroitre la justice territoriale, en améliorant laccessibilité et en réduisant les conflits. Ces problèmes sont analysés dans le cadre de lAire Métropolitaine de Lisbonne (AML) et on constate que ce thème napparait en réalité que comme secondaire, même si cest le plus souvent mentionné. On montre linfluence que les inégalités sociales ont sur la planification territoriale, on évoque les caractères densemble des politiques européennes et nationales et, finalement, les tendances que la mobilité présente dans le cadre de lAML, daprès les données statistiques et la lecture critique dautres publications.

Mots clés: Mobilité; inégalité; la planification et l'aménagement du territoire; Aire Métropolotaine de Lisbonne.

I. MOBILITY AND PUBLIC POLICY: PLANNING MORE JUSTICE?

The (re)production of inequality and the distribution of social and economic resources has been extensively studied in social sciences. However, the relationship between space and geographical mobility has not been sufficiently explored (Kaufmann, Bergman, & Joye, 2004; Ohnmacht, Maksim, & Bergman, 2009; Manderscheid, 2009). Furthermore, the social dimension is still a weak element in transport policies, which focus on economic and environmental concerns (Martens, 2006; Preston, 2009).

Mobility is an important arena for the wider discussion on spatial justice or social justice in space (Harvey, 1973; Soja, 1989; Marcuse, 2009; Fainstein, 2009) and the right to the city (Lefebvre, 1968; 1974; Mitchell, 2003; UNHABITAT, 2010). The ability of a person to move and to move other individuals, goods or information has become an important force of stratification (Manderscheid, 2009; Asher, 2010). This is the essence of many studies about the production of mobilities (Urry, 2000; Cresswell, 2006; Sheller & Urry, 2006; Carmo, 2009) and its relation to social inequality (Kaufmann et al., 2004; Cass, Shove, & Urry, 2005; Teles, 2005; Camarero & Oliva, 2008; Carmo & Santos, 2011). Unequal accessibility to urban space is frequently an outcome of a fragile, if even existing, articulation between mobility and spatial planning (Padeiro, 2012; Santos, 2014).

Soja (2010) uses an example of urban mobility to show the connection between public policy and the production of unfair spaces or inequalities in space. He analyses a judicial process which opposed a group of associations of public transport users against the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority (LAMTA). The final decision asserted that decades of discrimination against the transit-dependent urban poor had to be compensated: LAMTA was forced to prioritize investment in the quality of bus services and to ensure equal access to all forms of mass transport, instead of continuing the higher investment in road infrastructure.

Similarly, Camarero and Oliva (2008) observed how in the Spanish region of Pamplona-Iruñea there are citizens of different velocities according to class, family situation and mobility strategies. This was considered to be the combined result of the dynamics of urban sprawl and the increase of inequality in contemporary cities.

In general, studies on the social dimensions of mobility and transport tend to show concerns with the social usefulness of academic research (Bergmann & Sager, 2008; Ohnmacht et al., 2009) and to focus on the relation between social exclusion and transport (Garrett & Taylor, 1999; Church, Frost, & Sullivan, 2000; Hine & Grieco, 2003; Preston, 2009).

These discussions highlight a key debate on the role of public policies. Justice can be promoted not only in their content and results but also in the process in itself, namely through the participation of organized civil society, the population in general, specialists, etc. The demand for participation in planning grew when planning began to be recognized as a political and non-neutral activity (Miller, 1979; Hague & Jenkins, 2005).

Nonetheless, Fainstein (2009) and Cardoso and Breda-Vazquez (2007) alert to the possible over valorization of the communicative approach; the emphasis in procedural aspects of justice may fail to recognize or even help hide structural inequalities and power hierarchies. An open and public process does not necessarily promote the redistribution of resources or the rebalance of access to urban space. Much has to be discussed about how open and diverse the debate is, how does it reach populations that are excluded from other arenas of participation and how does it protect itself from NYMBism phenomena or electoral logics (Santos, 2012). Conflict appears unavoidable in planning: the conflict of interests in the planning process and the management of conflicting practices in space.

In sum, two fundamental questions are developed: is unequal access to space acknowledged in the reports and plans of mobility related policies? If so, what role is foreseen (or possible) for mobility and spatial planning in the design and implementation of more just policies? To answer these questions we must understand the background conditions and limitations that influence mobility and spatial planning in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (LMA).

II. MOBILITY AND SPATIAL PLANNING: THE EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL BACKGROUND

In the 90s, mobility issues acquired grown importance at the European level. Several guiding documents were published upholding the paradigm of sustainable urban mobility where mobility and spatial planning articulation is central (Costa, 2007).

At the European level, in what concerns urban mobility, the green paper (CE, 2007) stated three fundamental principles regarding inequality in mobility: (i) accessibility to certain services is a right; (ii) some conditions of a socially vulnerable individual or group result in reduced mobility; (iii) certain territories are marginalized regarding the availability or accessibility to services and the mobility conditions they provide to their inhabitants. In 2008, in the green paper on territorial cohesion (CE, 2008) transport policy was mentioned first in the group of policies that influence cohesion through its impacts on the implantation and distribution of activities and in its role on the improvement of connections to less developed regions and within these.

However, the subsequent transport white book (CE, 2011) suggests a more liberal orientation on public transport; the European mobility network should have a unique market freer from State intervention. It gives emphasis to polluter pays and user pays principles anticipating that transport users will pay for a higher proportion of the costs than today.

The publication of several documents, the participation in ministerial working groups, urban networks and projects at the European level have placed national and local governments in tune with European policy. There is a convergent trend of national systems and cultures of spatial planning in Europe although it is a tendency that happens mainly at the discursive level and with unequal incidence between countries and within them (Ferrão, 2011).

In Portugal, mobility policy-making is a particularly conflicting arena. There is at the same time a void and confusion in the definition of the responsibilities of each key actor, namely in what concerns separating public service from private businesses or establishing complementary territorial scales of action. In-between the central government, the road and public transport companies and the municipalities the multi-municipal intervention level has yet to mobilize. This is particularly negative in a metropolitan area such as Lisbon.

In mobility, as in other policy-making domains, over the last 30 years there was: (i) the persistence of outdated legal diploma, (ii) the multiplication of strategic guiding documents that strongly overlap, (iii) the absence of monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. There was a stronger investment in road development and the public transport network was maintained in the classic center-periphery model, although regional policy was aiming at sustainable and multipolar development for the Lisbon Metropolitan Areai. Consequently, the urban expansion of the last two decades has been based on a highly car dependent mobility.

Concerning Portuguese planning, Cardoso and Breda-Vázquez (2007) stated that it is still understood as a technical instrument of a neutral State aspiring to objectivity and refusing normative thinking. Viegas (2003) also alerted to the absence of explicit normative and political orientations in the planning process in Portugal: according to the author the result is that the plan reproduces mainly the vision of non-elected urban planners. To this matter, Ferrão (2011) points out that much is yet to be known about the social conditions underpinning the design and implementation of spatial planning policy.

In Portugal, the legislation in the area of transport, environment and spatial planningii connects these three domains, contemplates intermunicipal transport planning and mentions that attention should be paid to social and territorial equality.

However, progress had been made in the production of planning guide lines for better mobility, namely on the articulation of transport with spatial planning and the inclusion of social concerns. In 2009, three municipalities of the Lisbon Metropolitan Areas (LMA) edited a manual of sustainable mobility planning (AAAA, 2009), which resulted from participation in a European project. Also in 2009 a policy report on gender, environment and space (Gaspar & Queirós, 2009; Queirós & Costa, 2012) was published by the initiative of the Commission for Gender Citizenship and Equality. It dedicated a chapter to gender inequality in transport with some data for Portugal, namely regarding the use of car and public transport and the time expended in mobility. In 2010, the Portuguese national environment agency also published a manual on sustainable mobility (APA, 2010) and in 2011 the Director General for Spatial Planning and Urban Development (DGTODU) edited a volume dedicated to accessibility, mobility and urban logistics where the right to mobility is denoted (DGOTDU, 2011).

In the same year, the national institute for transport produced a guide for the elaboration of mobility and transport plans (IMTT, 2011). This document refers to vulnerable groups in mobility: the elderly, children and people with reduced mobility. It also declared a group of questions that a plan has to address which included the following: Are there areas or neighborhoods where problems of social and spatial exclusion persist due to an inadequate offer of transport infrastructure or services? (IMTT, 2011, p. 29).

These guiding documents discuss the problems of urban sprawl and its costs (financial and on the citizens quality of life) relating to mobility issues and underlining the great need to decrease car use. They reflect a profound knowledge of European orientations and policy-making and of other international experiences. They all suggest the promotion of urban densification and of land mix use and the importance of public information on mobility management. These are conditions expected to also uphold a better planning and an increased use of public transport. Unfortunately, these questions seem to be overlooked in the National Strategic Transport Plan (NSTP).

Recent financial problems in Portugal have critically redefined the agenda in the NSPT (MEE, 2011). The plan reports mainly the financial problems of the public transport companies. It is determined that only when the market does not function should the State ensure public service. In all, the states fundamental mission is not to provide a public transport service but to focus on offering support to the poorest. Reference is made to a social monthly pass (passe social+) which creates special discounts for low income people, although the number of eligible individuals declined compared to former policies. In addition, it doesnt recognize the role of the already formally established transport metropolitan authorities, since its regulating law from 2009 (Lei nº 1/2009, de 5 de Janeiro). There is a vague mention of the need for decentralization followed by a reference to the importance of municipalities. More recently, the political context has changed with the change of government and - although discourse seems to be changing - much remains to be determined in what concerns effective policy change.

III. LMAS MOBILITY AND SPATIAL PLANNING: NUMBERS AND DISCOURSES

1. Mobility trends in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (LMA)

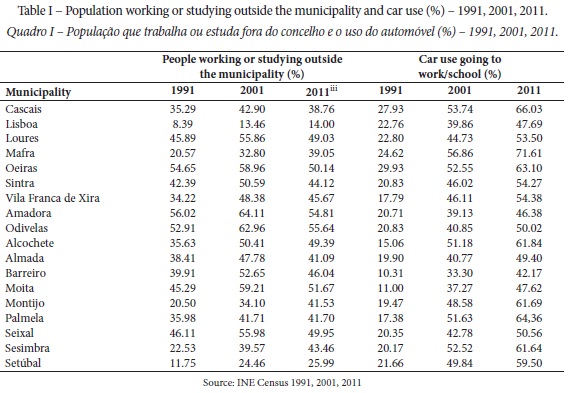

In the LMA the percentage of people that use a car to go to work or school has tripled in the last two decades. In 2011, the proportion of car use in the metropolitan area was 54% while the national percentage was 60%. In all 18 municipalities of the LMA the use of car has been rising (table I). In 1991, all showed fewer than 30% of the population using a car, while in 2001 all were above this value and many had already more than half of its movements made by car.

The great increase was from 1991 to 2001, also in what concerns mobility between municipalities (table I). In all, Lisbon continues to be the main centre and, in the south margin of the Tagus River, Setúbal performs as a subregional capital in some functions. However, while Setúbal has been losing the ability to retain its workers and/or students, Oeiras and Palmela have grown and became simultaneously the origin and destination of daily movements. Moreover, municipalities that integrated the first generation of suburbs (Amadora, Odivelas, Loures, Cascais, Sintra, Almada, Seixal, Barreiro) start to present, from 2001 to 2011, a better ability to maintain its population within the municipality. At the same time, Montijo, Sesimbra and Mafra, municipalities that traditionally show a more rural character, increase the percentage of the population leaving the municipality to work or study, which mainly relates to the recent growth of population.

Several factors influence the variation of behaviors between municipalities in what concerns car use (table I). The proximity to Lisbon, a better transport network and lower income seems to explain a lower use of the car in the case of Odivelas (50%), Amadora (46%), Moita (48%) or Barreiro (42%). Income is an important variable and the dominant socio-economic profiles in the municipalities have a say in the matter. The municipalities that show high levels of car use - Cascais (66%), Oeiras (63%) and Mafra (72%), Sesimbra or Alcochete (both 62%) - are different in what concerns social and professional profiles of the employed population (higher in the first two) or the level of accessibility and public transport offer (lower in the others). In 2003, the National Statistical Institute (INE) published a study which had some data on the social dimensions of mobility. The use of private transport above the average has been clearly associated with elite professional groups and higher qualifications as well as with gender: men use cars the most; and collective transport is fundamentally used by women and students (INE, 2003).

More recently these trends have been confirmed by a survey applied to a representative sample of Lisbon Metropolitan Area. The survey designed and applied by initiative of Localways research project reaches the same conclusions eleven years later: although income is fundamental, it is still mostly men that drive and women and young people that use public transport (Santos, 2015, p. 123-129). The elderly also use public transportation but mostly walk (idem).

Unfortunately, no similar study or variables are available for the 2011 census. There has been an improvement in the average time spent in pendular movements, from 32 to 26 minutes in the last decade (INE, Census 2001 and 2011). However it is not equal for all. Travel time can double comparing car use to public transport: the average time in the LMA for car users is 20.4 minutes while for public transport users it is 42.5 minutes. The smallest difference is in Mafra, from 12.1 (car) to 35.9 minutes (public transport), but in Barreiro, while car users spend in average 33.2 minutes in their home-work/school travels, public transport users take up to 55.9 minutes (INE, 2011). It seems the preference for car use, if possible, is not particularly irrational.

2. LMA municipal and supramunicipal policies

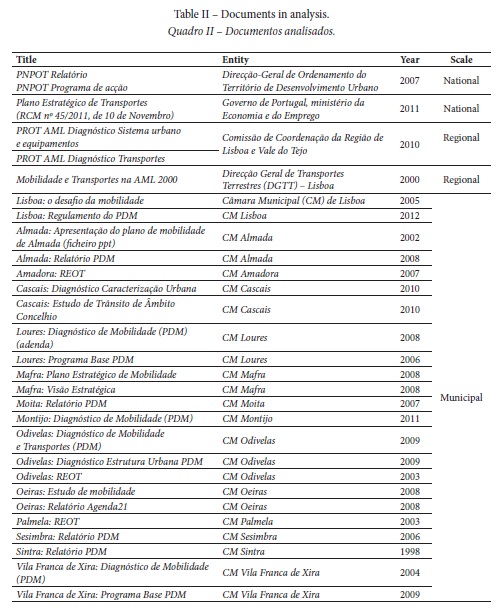

In the following section, we analyse how local and regional policies of mobility and spatial planning address questions of social inequality concerning mobility. Not all municipalities have specific studies on mobility and, in a total of 18, only three developed their own extensive surveys reporting on sociodemographic features of mobility (Lisbon, Oeiras and Cascais). Local authorities make use of their technical teams and frequently of private consulting or non-profit research centers. Through a critical reading and qualitative content analysis of the main documents (table II) we explored how inequality in mobility is conceived by urban planning in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. The content analysis was focused on identifying if and how inequality in peoples mobilities was perceived. If inequality was mentioned, we searched for the most referenced spatial or social variables and which measures, if any, were designed to oppose this inequality. The content analysis was computer assisted though no quantitative outputs were produced since it was mainly the discourse, symbols and values used that were under focus.

In all the documents environmental sustainability is mentioned in relation to mobility. This is not true for social inequality. There is a lack of information on social differentiation, although all documents were produced after the publishing of the INE (2003) report. Most of the municipalities even used other information of this report but did not refer to the differences identified concerning age, economic resources or gender.

Mobility and spatial planning are related in all documents through the role of infrastructure and transport in the structure and hierarchy of urban space. They all establish parallels between the development of the road network and transport services and the extension of employment and residential areas, describing how the municipalities have grown in the last decades. Also, in all is outlined the problem of urban sprawl in the LMA.

Inequality is a poorly referenced subject. Different notions such as social equity, inequality or social differentiation are used. Although they have distinct and debatable meanings, we identified them as an ensemble due to the scarcity of references. Thus this analysis is generally identifying every time social or spatial variables are mentioned to refer to unequal access to space or mobility. This general reference is differently presented throughout the documents. The first and more frequent reference is a general consideration of the principle itself in spatial planning, rarely detailing what it means or how it is materialized. In the national spatial planning policy report (DGOTDU, 2007) the notion of social and territorial equity, being a central principle, relates mainly to the notion of territorial cohesion of the European Commission report (2009). At the regional level, in the transport study that precedes the regional spatial plan, the document refers to equity as a priority and to mobility as a right (PROTAML, Diagnóstico Transportes, CCDRLVT, 2010). Yet the regional plan is currently suspended. The only other document at the supramunicipal level is the pioneer experience of the Intermunicipal Transport Plan (PMTI) of Barreiro, Moita, Palmela, Seixal and Sesimbra, motivated by the planning of a third Tagus River crossing (AAAA, 2013).

Still, some documents identified specific variables for conditioning mobility: age, life cycle; the existence of children in the family; and the specific needs of disabled people. In documents of Lisbon, Oeiras, Cascais, Odivelas and Loures the social dimensions of mobility are more present. In these municipalities the relation between mobility and spatial planning is more thoroughly examined in the specific local contexts of each municipality. In Lisbon, Cascais and Oeiras the approach is quite similar. Besides having common urban features, in these municipalities the team responsible for the plan was the same (TIS.pt). The documents cross-examine social and demographic features of the population with levels and modes of travel concluding that age, the presence of children and economic resources tend to produce different mobility patterns: people with more economic resources tend to use the car the most as well as people with children. Ageing is the problem most mentioned, particularly in Lisbon. Children are also identified as a group that should have special attention related to school transport. Also, in a more normative tone, the Lisbon and Oeiras studies start with notes on the right to mobility (CML, 2005, p. 6; CMO, 2008, p. C-4). However, an absence must be disclosed: no consideration is made regarding gender. And if some references are made to equity, cohesion, justice or the right to mobility, much rarer are concrete proposals.

One of the factors that most distinguishes the municipal mobility strategies could be the team which designs it. In Oeiras, Cascais and Lisbon TIS.pt was the consultant company responsible (which is directed by José Manuel Viegas, currently Secretary-General for the OECD International Transport Forum). As in Mafra and Vila Franca de Xira, the focus on public space design considering reduced mobility groups (the elderly, people with disabilities, people with children) is produced by m.pt, founded by Paula Teles (the national coordinator of the city network that promotes mobility for all).

The municipalities use their technical teams but also make resource of external consultingiii. A different kind of actor involved is the research center, such as, e-geo and the environment engineering department (FCT) from Universidade Nova de Lisboa (Amadora and Odivelas environment and spatial planning reports – REOT). Some individualities are present in these different arenas: private consulting, public universities research, third sector as well as political roles. This probably reinforces the blurred lines in the separation of actors, their nature and corresponding responsibilities (public/private; political/ academic/ consulting, etc.). Nonetheless, it has also been the vehicle for exchange between academic production and policy making and through different scales of thinking and intervention (European, national, regional, local).

IV. MORE JUSTICE IN PLANNING? DISCOURSE FACES ACTION

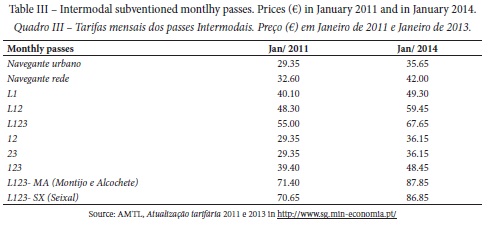

Surely mobility and spatial planning policy is not limited to the content and discourse of these documents. In Portugal, recent profound changes are still hard to measure. However, if some change in discourse is denoted, central government policies concerning public subvention to transport service and pricing clearly worsen mobility conditions. Fares are higher (table III) and there is a discount reduction for the elderly, students or the low income population (Portaria nº 272/2011, de 23 de Setembro, Diário da República, 1ª série – nº 184 and Portaria nº 36/2012, de 8 de fevereiro, Diário da República, 1º série – nº 28). In three years the established prices for the subventioned intermodal monthly passes increased up to more than 10 euros, according to the information available on the Transport Metropolitan Authority website (table III). Variation rates in the prices of monthly passes from 2011 and 2014 are all above 20% when for the same period the employees national average salary increased 0.48% (PORDATA, 2016iv).

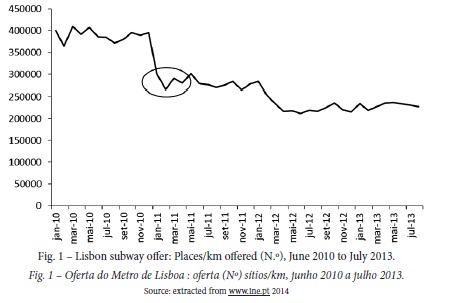

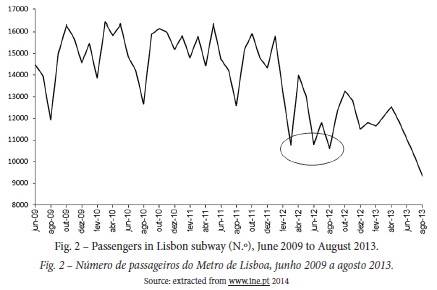

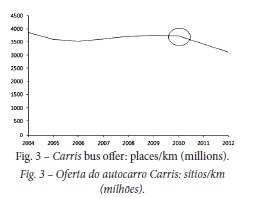

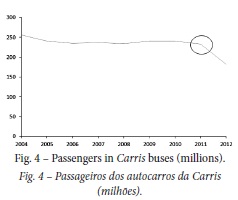

However, there are signs that the public service has been reducing its offer. Even if the demand for transport unfortunately decreases due to the rise of unemployment, the public transport offer decrease seems to be worse. We underline the cases of Carris and Metropolitano de Lisboa, the bus and subway public companies which operate in the Lisbon municipality and its outskirts where the public offer decreased before the decrease of passengers. (figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Conversely, some services have been qualified. Using the internet there are now several options to better plan our travels with the estimation of time, length and costs. In the last decade some buses and trains have been equipped with more visual and sound information about the travel, its stops and estimated waiting time. Nonetheless, this does not benefit all social groups equally: age, income or qualification tend to influence the access to these innovations. Also, the material ticket system has been undergoing simplification with the Lisboa Viva card functioning in the majority of the metropolitan operators, though the organizing system behind it has yet to be tackled. In the Autoridade Metropolitana de Transportes de Lisboa (AMTL) website there is the list, reviewed in august 2013, of the 1 241 titles that can be bought in the LMA transport network. These are from 16 different operators and 551 of them are monthly passes. Many of them are not subventioned, not applying the discounts referred to above.

V. CONCLUDING REMARKS

The expression and reproduction of social inequalities in peoples mobility is inseparable from the urban structure and the private and public agents that produce it. Some tendencies concerning age, gender, physical disabilities and socio-economic resources were clearly identified in international and national studies and also in some local surveys. Nonetheless, in the majority of the documents social concerns on mobility are peripheral and concrete measures to promote spatial justice have not been identified.

At the present time, there are many guiding documents at the European, national and regional level that aim to promote a more sustainable mobility establishing social equity as a priority. However, some of these documents were published after the municipal studies and plans analysed. Municipalities examine and plan mobility in different ways depending on economic and technical resources and planning cultures. If financial resources and political determination seem sometimes to be missing, some regional and local actors show the know-how, which is a central resource.

LMA unequal mobility conditions promote conflicting spatial practices, in which the use of car has been clearly benefited. This is also an outcome of decades of policy-making disregarding and thus helping to reproduce unequal conditions of living and moving in the city-region. The delay and blockage at the metropolitan level of planning may have been one of the strongest factors for the continuing lack of articulation between spatial planning and mobility. If the city is left to grow according to road infrastructure development and without articulation with public transportation, it will quite predictably promote unequal access to urban space and unsustainable mobility practices.

Unfortunately, if until recently European policy-making would provide wise guide lines in the opposite direction, the current parallel between the white book and the national transport plan suggests mainly the over focus on financial matters and the disregarding of the regional level of action. This has already been materialized in political actions in the transport sector, namely in pricing and reduction of public service. However, other institutions at the national and local level have not yet succumbed to this narrowing conception. Their manuals and guiding documents can considerably contribute to capacity building providing resources for planning sustainable mobility that promotes socio-spatial inclusion. Finally, this background enables that the choice between these two conflicting visions on mobility is highly dependent on the local political will and endorses the persistent blockage of a metropolitan strategic planning.

Evidently, to aim for spatial justice in mobility involves broader questions regarding employment, work-family conciliation, environment, or urbanization models. An improved mobility planning demands strong articulation with spatial planning or employment policies, for instance. Nonetheless, transport policies can be more socially aware through the deeper knowledge of mobility inequalities and the promotion of better circulation and accessibility for vulnerable groups. Thus preventing that social exclusion is worsened by territorial marginalization. The concern with inequality in access to urban space requires multilevel intervention, beyond the transport domain, though necessarily producing effects in mobility.

Furthermore, if attention must be paid to procedural aspects we should also ensure that the process of planning effectively produces results that fight socio-spatial inequalities. To ensure spatial justice we firstly have to identify the emerging inequalities in space and to recognize the role of public policy in their (re)production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to thank the most valuable suggestions and comments of João Mourato. This article was written in the context of a Ph.D. funded by the FCT (reference SFRH/BD/71997/2010) and in connection with the FCT project LOCALWAYS (reference PTDC/ATP-EUR/5023/2012).

REFERENCES

AAAA (2009). Manual de Boas Práticas para a Elaboração de um Plano de Mobilidade Sustentável [Good Practices Guide for the Elaboration of a Sustainable Mobility Plan]. Câmaras Municipais do Barreiro, Moita e Loures. Retrieved from: http://www.cm-loures.pt/doc/projectos/MARE/Manual.pdf [ Links ]

AAAA (2013). Elaboração do Plano de Mobilidade e Transportes Intermunicipal da Área de Influência da TTT (Margem Sul). Sumário Executivo [Elaboration of the Intermunicipal Mobility and Transport Plan of the Área de Influência da TT (South Bank). Executive Summary]. Lisbon. Retrieved from: https://sites.google.com/a/dhv.pt/pmti/home/conteudos [ Links ]

APA (2010). Manual de Boas Práticas para uma Mobilidade Sustentável [Good practices Guide for Sustainable Mobility]. Lisbon: Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente. Retrieved from: http://sniamb.apambiente.pt/mobilidade/ [ Links ]

Asher, F. (2010). Novos Princípios do Urbanismo seguido de Novos Compromissos Urbanos [New Principles of Urbanism, followed by New Urban Commitements]. Lisbon: Ed. Livros Horizonte. [ Links ]

Bergmann, S., & Sager, T. (2008). The Ethics Of Mobilities. Rethinking Place, Exclusion, Freedom And Environment. Ashgate E-book. [ Links ]

Camarero, L., & Oliva, J. (2008). The social face of urban mobility in Spain. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32, 344-362. [ Links ]

Cardoso, R., & Breda-Vázquez, I. (2007). Social Justice as a guide to Planning Theory and Practice: Analysing the Portuguese Planning System. International Journal of Urban and Regional, 31(2), 384-400. [ Links ]

Carmo, R. M., & Santos, S. (2011). Mobilidade social e confiança [Social mobility and trust]. In R. M. Carmo (Org.), Entre as Cidades e a Serra. Mobilidades, Capital Social e Associativismo no Interior Algarvio [Between cities and saws. Mobilities, social capital and associativism in Interior Algarvio] (pp. 45-69). Lisbon: Ed. Mundos Sociais. [ Links ]

Carmo, R. M., & Simões, J. A. (Orgs.). (2009). A Produção das Mobilidades. Redes, Espacialidades e Trajectos. [Production of Mobilities. Networks, Spatialities and Paths]. Lisbon: Ed. Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

Cass, N., Shove, E., & Urry, J. (2005). Social exclusion, mobility and access. The Sociological Review, 53(3), 539-555. [ Links ]

Comissão Europeia (CE) (2007). Livro Verde - Por uma nova cultura de mobilidade urbana [Green Paper - Towards a new culture for urban mobility]. Comissão Europeia. Retrieved from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:52007DC0551:PT:HTML:NOT [ Links ]

Comissão Europeia (CE) (2008). Livro Verde sobre a Coesão Territorial Europeia - Tirar Partido da Diversidade Territorial [Green paper on territorial cohesion: turning territorial diversity into strength]. Retrieved from: http://www.dgotdu.pt/ue/LivroVerdeTC_pt.pdf [ Links ]

Comissão Europeia (CE) (2011). Livro Branco - Roteiro do espaço único europeu dos transportes – Rumo a um sistema de transportes competitivo e económico em recursos [White Paper - Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area – Towards a competitive and resource efficient transport system]. Comissão Europeia. Retrieved from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0144:FIN:PT:PDF [ Links ]

Comissão de Coordenação e Desenvolvimento Regional de Lisboa e Vale do Tejo (CCDRLVT) (2010). Plano Regional de Ordenamento do Território da Área Metropolitana de Lisboa – Diagnóstico Sistema de Transportes [Spatial Planning Regional Plan of the Lisbon Metropolitan Area – Diagnosis of the Transport System]. Retrieved from: http://consulta-protaml.inescporto.pt/plano-regional/relatorio-do-plano/relatorios-sectoriais-de-caracterizacao-e-diagnostico [ Links ]

Church, A., Frost, M., & Sullivan, K. (2000). Transport and Social Exclusion in London. Transport Policy, 7, 195-205. [ Links ]

CML (2005). Lisboa: o desafio da mobilidade [Lisbon: the challenge of mobility]. Lisbon: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. Retrieved from: http://cidadanialxmob.tripod.com/mobilidade.pdf [ Links ]

CMO (2008). Estudo de Mobilidade e Acessibilidades do Concelho de Oeiras - Relatório de Síntese [A Study of Mobility and Acessibility in Oeiras – Synthesis Report]. Oeiras: Câmara Municipal de Oeiras. Retrieved from: http://www.cm-oeiras.pt/noticias/Paginas/MelhorMobilidade,MelhorOeiras33.aspx [ Links ]

Costa, N. M. (2007). Mobilidade e Transporte em Áreas Urbanas. O caso da Área Metropolitana de Lisboa. [Mobility and Transport in urban areas. The case of Lisbon Metropolitan Area]. (PhD dissertation). Lisbon: Universidade de Lisboa. [ Links ]

Cresswell, T. (2006). On the Move. Mobility in the Modern Western World. Nova Iorque: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cresswell, T., & Merriman, P. (Eds.) (2011). Geographies of mobilities: practices, spaces, subjects. London: Ashgate. [ Links ]

DGOTDU (2007). Programa Nacional de Política de Ordenamento do Território. Relatório [National Program of Spatial Planning Policy. Report.]. Lisbon: Direcção-Geral do Ordenamento do Território e Desenvolvimento Urbano. Retrieved from: http://www.territorioportugal.pt/pnpot/ [ Links ]

DGOTDU (2011). Acessibilidade, Mobilidade e Logística Urbana [Acessibility, Mobility, and Urban Logistics]. Lisbon: Direcção-Geral do Ordenamento do Território e Desenvolvimento Urbano. Retrieved from: http://www.dgotdu.pt/detail.aspx?channelID=D1021651-9D09-42BD-A5E2-E31A40AB0F3D&contentId=AF82B2F3-48C8-4B02-A63B-DB6BD44C16DF [ Links ]

Fainstein, S. (2009). Spatial Justice And Planning. Spatial Justice N° 01. [ Links ]

Ferrão, J. (2011). O Ordenamento do Território como Política Pública [Spatial Planning as a Public Policy]. Lisbon: Ed. Calouste Gulbenkian. [ Links ]

Forester, J. (1987). Planning In the Face of Conflict: Negotiation and Mediation Strategies in Local Land Use Regulation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 53(3), 303-314. [ Links ]

Garrett, M., & Taylor, B. (1999). Reconsidering Social Equitity in Public Transit. Berkeley Planning Journal, 13, 6-27. [ Links ]

Gaspar, J., & Queirós, M. (Coord.) (2009). Género, Território e Ambiente. Estudo de diagnóstico e criação de indicadores de género na área do ambiente e território e elaboração de um guia para o mainstreaming de género [Gender, Territory, and Environment. A Study of Diagnosis and Creation of Gender Indices in the Area of Environment and Territory and Elaboration of a Guide for Gender Mainstreaming]. Lisbon: Universidade de Lisboa, Centre of Geographical Studies and Comissão para a Cidadania e a Igualdade de Género. Retrieved from: http://www.igualdade.gov.pt/INDEX_PHP/PT/DOCUMENTACAO/RELATORIOS/120_GENERO_TERRITORIO_E_AMBIENT.HTM [ Links ]

Hague, C., & Jenkins, P. (Orgs.) (2005). Place Identity, Participation and Planning. Oxford: Routledge, Oxfordshire. [ Links ]

Harvey, D. (1973). Social Justice and the City. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Hine, J., & Grieco, M. (2003). Scatters and clusters in time and space: implications for delivering integrated and inclusive transport. Transport Policy, 10, 200-306. Retrieved from: http://www.jssj.org/archives/01/media/dossier_focus_vo5.pdf [ Links ]

IMTT (2011). Guia Para a Elaboração de Planos de Mobilidade e Transportes [Guide for Elaboration of Mobility and Transport Plans]. Lisbon: Instituto da Mobilidade e dos Transportes Terrestres. Retrieved from: http://www.imtt.pt/sites/IMTT/Portugues/Planeamento/EstudosProjectosCurso/PacotedaMobilidade/Paginas/QuadrodeReferenciaparaPlanosdeMobilidadeAcessibilidadeeTr ansportes.aspx [ Links ]

INE (2003). Movimentos pendulares e organização do território metropolitano: área metropolitana de Lisboa e área metropolitana do Porto: 1991/2001 [Commuting and the organization of metropolitan territory: Lisbon Metropolitan Area and Porto Metropolitan Area: 1991/2001]. Lisbon: Ed. Instituto Nacional de Estatística. [ Links ]

Kaufmann, V., Bergman, M., & Joye, D. (2004). Motility: Mobility as Capital. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28(4), 745-756. [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H. (1968). Le droit à la ville [The right to the city]. Paris: Ed. Anthropos. [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H. (1974). La Production de lEspace [Production of Space]. Paris: Ed. Anthropos. [ Links ]

Manderscheid, K. (2009). Unequal Mobilities. In T. Ohnmacht; H. Maksim, & M. Bergman (Eds.), Mobilities and inequality. London: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Martens, K. (2006). Basing Transport Planning on Principles of Social Justice. Berkeley Planning Journal, 19, 1-17. [ Links ]

Marcuse, P. (2009). Spatial Justice: Derivative but Causal of Social Injustice. Justice Spatiale | Spatial Justice, 1. [ Links ]

MEE (2011). Plano Estratégico dos Transportes - Mobilidade Sustentável, Horizonte 2011-2015 [Transport Strategic Plan – Sustainable Mobility, Horizon 2011-2015], RCM n.º 45/2011 de 10 de Novembro, Diário da República, 1.ª série N.º 216 10 de Novembro de 2011. [ Links ]

Miller, T. (1979). The emergence and impact of participatory ideas on Swedish planning and local government. Scandinavian Political Studies, 2(4), 333-349. [ Links ]

Mitchell, D. (2003). The Right to the City. Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. New York: The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Ohnmacht, T., Maksim, H., & Bergman, M. (Eds.) (2009). Mobilities and inequality. London: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Padeiro, M. (2012). Conciliar os transportes e o ordenamento urbano: avanços recentes e aplicabilidade em áreas metropolitanas portuguesas [Reconciling transport and urban planning: recent advances and applicability in portuguese metropolitan areas]. Cidades, Comunidades e Territórios, 25, 1-20. [ Links ]

Preston, J. (2009). Epilogue: Transport policy and social exclusion-Some reflections. Transport Policy, 16(2009), 140-142.

Queirós, M., & Costa, N. (2012). Knowledge on Gender Dimensions of Transportation in Portugal. Dialogue and Universalism, 3(1/2012), 47-69.

Santos, S. (2012). Participação em planeamento territorial e o caso do orçamento participativo. Leituras a partir de um concelho interior algarvio [Participation in territorial planning and the case of participatory budgeting. Readings from an interior county in Algarve]. CIES e-Working Paper N.º 128/2012, Lisbon: CIES-IUL. Retrieved from: http://cies.iscte.pt/np4/?newsId=453&fileName=CIES_WP128_Santos.pdf [ Links ]

Santos, S. (2014). Mobilidade geográfica e desigualdades sociais: lugares e caminhos de investigação sociológica sobre território. [Geographic mobility and social unequalities: places and paths of sociological research on territory]. CIES e-Working Paper, Nº 179/2014, Lisbon, CIES-IUL. Retrieved from: http://cies.iscte.pt/np4/?newsId=453&fileName=CIES_WP179_Santos.pdf [ Links ]

Sheller, M., & Urry, J. (2006). The new mobilities paradigm. Environment and Planning A, 38, 207-226. [ Links ]

Soja, E. (1989). Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory. London: Verso Press. [ Links ]

Soja, E. (2010). Seeking Spatial Justice. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Teles, P. (2005). Os Territórios (Sociais) da Mobilidade. Um Desafio para a Área Metropolitana do Porto [Territories (socials) of mobility. A challenge for the Porto Metropolitan Area]. Aveiro: Ed. Lugar do Plano. [ Links ]

UNHABITAT (2010). The Right to the City: Bridging the Urban Divide. Rio de Janeiro. ONU, 5º Fórum Urbano Mundial. [ Links ]

Urry, J. (2000). Sociology beyond societies. Mobilities for the twenty-first century. Londres: Routledge. [ Links ]

Viegas, J. M. (2003). Estratégias Urbanísticas e Governabilidade [Urban Strategies and Governance ]. In N. Portas, Á. Domingues, & J. Cabral (Eds.), Políticas Urbanas: Tendências, Estratégias e Oportunidades [Urban Policies: Trends, Strategies and Opportunities] (pp. 260-273). Lisbon: Ed. Calouste Gulbenkian. [ Links ]

Recebido: Maio 2015. Aceite: Novembro 2016.

NOTAS

iSee Regional Spatial Plan (PROT), RCM nº 68/2002, Diário da República – I Série B, N. 82, 8 de Abril de 2002 DIÁRIO DA REPÚBLICA I SÉRIE-B iiPortuguese fundamental laws in these matters: (I) Transport - Lei de Bases do Sistema de Transportes Terrestres (Lei nº10/90, de 17 de Março), Plano Estratégico de Transportes (RCM nº 45/2011, de 10 de Novembro); (II) Environment - Lei de Bases do Ambiente (Lei nº 11/87 de 7 de Abril); (III) Spatial Planning- Lei de Bases do Ordenamento do Território (Lei 48/98, de 11 de Agosto), Regime Jurídico dos Instrumentos de Gestão Territorial (Decreto-Lei 380/99, de 22 de Setembro) e o Programa Nacional da Política de Ordenamento do Território (Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.o 41/2006, de 27 de Abril). Spatial planning and environment fundamentals laws have recently been substituted by new diplomas in 2014. iiiSidónio Pardal, on the coordination of the Montijo master plan revision; Transitec Portugal e Semaly Portugal designed the Acessibility Plan in Almada; Mercaplus on a mobility study for Loures; Cised Consultores, Geoideia – Estudos de Organização do Território and Planarq – Planeamento e Arquitectura, also on a mobility study for Vila Franca de Xira; which was used by Plural for the Vila Franca de Xira master plan revision; and then m.pt was responsible for Mafra and Vila Franca de Xira more recent accessibility plans; TIS.pt in Lisboa, Oeiras, Cascais and the regional plan transport, PROTAML; DHV. SA for the PMTI, the only intermunicipal plan; way2go associados in Sesimbra accessibilities plan; and Parque Expo designed Mafra strategic plan. ivhttp://www.pordata.pt/Portugal/Sal%C3%A1rio+m%C3%A9dio+mensal+dos+trabalhadores+por+conta+de+outrem+remunera%C3%A7%C3%A3o+base+e+ganho-857 confirmed 28/09/2016.