Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.97 Lisboa maio 2014

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Spatial dimension changes in second hand housing prices in Alcalá de Henares and León (Spain)

Dimensão espacial das mudanças nos preços da habitação em segunda mão em Alcalá de Henarese León (Espanha).

María Jesús González González1 María Luisa de Lázaro y Torres2

1 Associated Professor of Human geography. Universidad de León. E-mail: mjgong@unileon.es

2 Associated Professor of Human geography. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. E-mail: mllazaro@ghis.ucm.es

ABSTRACT

The objective of this study is to show different recent trends (20012009) in second hand housing prices in Spain and in different neighbourhoods in Alcalá de Henares and León, both of which are cities with very diverse economic and demographic characteristics. The first is a city in the metropolitan area of Madrid, with high land prices. The increasing demand for housing in Alcalá de Henares is a good alternative for households, in view of high prices in Madrid. The second is Léon, the capital of the province of León, which is undergoing a depopulation process. We will demonstrate that house price dynamics is a local phenomenon and national or regional level data conceal interesting differences within cities (districts and neighbourhoods). The latest rise and decline in housing prices is clearly visible on the outskirts and sometimes non existent in the town centre area.

Keywords: second hand housing prices, medium sized Spanish towns, newspaper real estate advertisements, Spain.

RESUMEN

Dimensión espacial de los cambios en los precios de la vivienda de segunda mano en Alcalá de Henares y león (España). El objetivo de este estudio es mostrar las diferentes tendencias recientes (2001 2009) de los precios de la vivienda de segunda mano en España y en los distintos barrios urbanos de Alcalá de Henares y León, ciudades con características económicas y demográficas muy diferentes. La primera es una ciudad en el área metropolitana de Madrid, con valores elevados de los precios del suelo. La creciente demanda de vivienda en Alcalá de Henares es una buena alternativa para las familias, dado los altos precios de Madrid. La segunda es León, capital de la provincia de León, que se encuentra en un proceso de despoblación. se muestra que la dinámica de precios de la vivienda es un fenómeno local y que los datos a nivel nacional o regional esconden importantes diferencias dentro de las ciudades (distritos y barrios). La última subida y la caída de los precios de la vivienda es claramente visible en la periferia y que a veces es inexistente encentro de la ciudad.

Palabras clave: Precios de la vivienda de segunda mano, ciudades medianas españolas, anuncios inmobiliarios, España.

RESUMO

O objectivo do estudo é mostrar as diferentes tendências recentes (2001 2009) dos preços da habitação em segunda mão no conjunto de Espanha e em distintos bairros urbanos de Alcalá de Henares e León, cidades com características económicas e demográficas muito distintas. A primeira é uma cidade na área metropolitana de Madrid, com valores elevados do preço do solo. A crescente procura de habitação em Alcalá de Henares é uma boa alternativa para as famílias, atendendo aos preços elevados de Madrid. A segunda é León, capital da província de León, que vive um processo de despovoamento. Mostra-se que a dinâmica dos preços das casas é um fenómeno local e que dados a nível nacional ou regional escondem diferenças importantes dentro das cidades (distritos e bairros). A ascensão e queda mais recente nos preços das casas é claramente visível na periferia e é às vezes inexistente no centro da cidade.

Palavras-chave: Preços da habitação em segunda mão, cidades médias espanholas, anúncios imobiliários, Espanha.

RÉSUMÉ

Variation des prix de vente des biens immobiliers doccasionà Alcalá de Henares et à León (Espagne).Cette étude a permis de comprendre les tendances actuelles (2001 2009) des prix de vente du logement doccasion en Espagne, et plus particulièrement à Alcalá de Henares et à León. Ces deux villes sont différentes aux points de vue économique et démographique. Alcalá, ville de la zone métropolitaine de Madrid, affiche un prix très élevé du bien immobilier (terrain) au mètre carré, mais cependant moins cher quà Madrid. Cette condition avantageuse pour les ménages qui décident dhabiter près de la capitale, explique la demande croissante de logements à Alcalá de Henares. León, capitale de province a, par contre, subi un processus de dépeuplement progressif et sa population a vieilli. On vérifie que la dynamique des prix du logement doccasion obéit surtout à des facteurs locaux et que les prix du logement traduisent dimportantes différences, aussi bien au niveau national ou régional quà lintérieur même des villes (arrondissements, quartiers). Ainsi, les dernières hausses et baisses des prix de limmobilier sont bien plus évidentes dans les zones périphériques quau centre ville, où elles sont à peine ressenties.

Mots-clés: Immobilier, prix, logement doccasion, villes moyennes, annonces, Espagne.

I. INTRODUCTION

It is well known that the continuous growth in construction and the number of dwellings in Spain since the end of the 1990s has resulted in the unprecedented growth of cities. This unstoppable boom has been matched by the continuous increase in housing prices since the end of the 1990s which, as in other European countries (Arestis et al., 2009), has stopped radically after a short period of slowing down. The rate of construction in Spain has by far exceeded that of other community countries, so the recent halt in construction has been very brusque. Not all cities have the same behaviour in dwelling prices, although some general tendencies maybe similar. Neighbourhood data show how location is very important in the real estate market.

The purpose of our study is focused on demonstrating how national tendencies of official sources are not fulfilled in all regions and towns. We have used different neighbourhoods in two medium sized cities with very different demographic and economic characteristics, Alcalá de Henares and León, to compare the price of second hand housing and demonstrate this fact. We show different prices in different neighbourhoods, although these tendencies depend on how close the neighbourhood is to the city centre. in Spain, city centres have a very different dynamic from authors study prices in cities globally on a regional scale and compare them with the principal economic variables within a macro economical framework (Ayuso et al., 2006).they relate house prices with the population and age composition; rents or incomes; mortgage rate reductions that help consumption and increase demand; credit availability, the general economic situation, demography, housing stock, the mortgage market, etc. (Leirado, 2006; Martínezet al., 2006; Menéndez, 2006; Leirado, 2006; Muellbauer and Murphy, 2008; Browning, et al., 2009; Slacalek, 2009; Muellbauer and Murata, 2010).

It is not our objective to look for a valid model to explain the dynamics of house prices throughout time on a general or regional scale, as other authors have done based on demand. Despite these efforts, a completely satisfactory valid model has yet to be found (Muellbauer, 2010). There are also hedonic models for estimating relationships between housing prices and the physical attributes and geographical characteristics of homes (Whitehead, 2006; aron et al, 2010; Chen et al., 2009) but due to the housing markets characteristic features of locational effects and market segmentation, these assumptions are not tenable in many empirical applications. Accordingly, there are an increasing number of applications of spatial econometric and statistical techniques that continue to appear in the literature. With the rising popularity of these techniques, it seems important to assess the relative merits of various Models, and to develop guidelines to support the use of different modeling (Paéz et al., 2008: 1577).

This does not stop connections, already confirmed in many other studies, between second hand house prices and the income of the population, demographic dynamic, housing stock, types of credit interest from being detected (George and Tatian, 2009).We have not been looking for the ripple effect from a leading region, such as for example, the main metropolitan areas to the adjacent ones, which happen in London (Cameron, Muellbauer and Murphy, 2006: 25).

Some authors state that Differentials in housing price changes across regions have been relatively unexplored (Meen, 2001). The differences between neighbourhoods or districts within the same city have been explored even less; therefore the aim of the present study is to contribute to that line of investigation. Meen (2001) points out that the main implications for intraurban housing market segmentation are neighbourhood quality and deprivation. But it can be added that a central location and the age of the building are also very important.

this study will confirm existing differences in the price of dwellings situated in different city neighbourhoods or districts. The objective is to show the existence of different trends of behaviour in prices of second hand apartment blocks in different neighbourhoods or districts of the city, in the inner city and old city; in urban expansion areas of the town in the 19th century or early 20th century (ensanche), or in peripheral areas and more recently built ones. The dynamics of fluctuations in these prices in the present decade are also different depending on the area in the city. Some clarifications therefore need to be made about this general tendency that most authors refer to, with regard to their sources of information, how the mean prices are worked out, and particularly, differences in the behaviour of the evolution of prices in different neighbourhoods. The behaviour of prices in the inner city in Spain is very different from other countries such as the UK or Us, where neighbourhoods are polarised between wealthy suburbs and a poor inner city.

House price dynamics have an important local component. National or regional generalizations obscure district and neighbourhood differences within cities. The present study seeks to interpret house prices within the framework of decreased demand, which will probably continue in Spain for a long time. We see that recent real estate prices have not dropped but levelled out. Some of them were overvalued years ago, and now they have lost their overvaluation. Future tendencies point out lower prices. The unprecedented economic crisis will not change this tendency for the moment.

This paper is set out as follows: after this introduction, section ii is a general framework about housing prices in Spain. Section iii deals with the case studies: Alcalá de Henares and León. The last section contains the conclusion.

II. HOUSING PRICES IN SPAIN

In the last fifteen years, the building industry has been the basic motor of the Spanish economy, and as a result, certain problems generated by this activity have not been considered. There have been no suitable policies, such as support to renovation, to reduce this indiscriminate construction, sufficient promotion of rented housing to reduce the number of empty dwellings or attention to the national and international second home market.

1. The increase and overvaluation of real estate in Spain

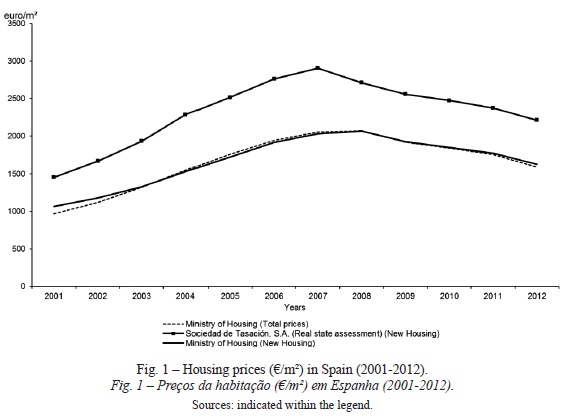

The constant increase in construction in recent years due to the profit it generates has led to the growth and transformation of the traditionally compact city, which has become more dispersed and fragmented, with low density populations and predominantly single family units (García Palomares and Gutiérrez Puebla, 2007). Marked functional and social segregation has occurred in these new residential areas in most spanish cities. Increased house prices also affect building land by producing substantial capital gains. In this context, land has greater repercussions on the final price of a building. The result is that new housing is more costly than second hand housing. This result also depends on the source, the evaluation by firms such as the sociedad de tasaciones, s.a. which overvalued realestate until 2007 (fig. 1), while in 2001 its valuations were not as high as other sources (Tinsa, 2010, 2011).

An empirical fact has thus been demonstrated. In recent years, property prices have been on the rise, which was the general trend until 2007, the rise being above other economy indicators, for example, the natural increase expected in times of expansion in GDP and CPI. The upward trend in house prices has slowed down since 2007, as shown in the graph, though there are differences according to the source of information used. Some authors believed that there would be a huge property crash (Lamothe and Luna, 2006), some thought that there would be a housing bubble (García Montalvo, 2006) and others that property would be overvalued (Bank of Spain, study papers). the international Monetary fund (2008) considers housing prices to be overvalued by 20%.the observed overvaluation is confirmed by the fact that in recent years real house prices have been higher than those estimated.

Similar figures in overvaluation (30%) have been seen in other countries, such as the UK until 20032004 (Ayuso and Restoy, 2006a). the OECD (2005) shows that real house prices (nominal price deflated by the overall consumer price index) have been rising since 2001 in several countries (Ireland, UK – until 2004 –, Australia – until 2003 –, Spain, Norway, France, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Canada, Italy, China from 2003 specially focused on big cities like shanghai...) helped by low interest rates and in some cases also by sub prime mortgages that have kept housing affordable. the price of a medium sized house in the Us doubled during 2000 2006. in other countries (Netherlands or Switzerland), the price rise is moderate. in some others, prices have not risen at all in the present decade (Germany, Japan, Korea...) because interest rates have not decreased. Other countries (Austria) that have not liberalised credit are not affected by these increases.

2. Indicators influencing the general increase in housing prices

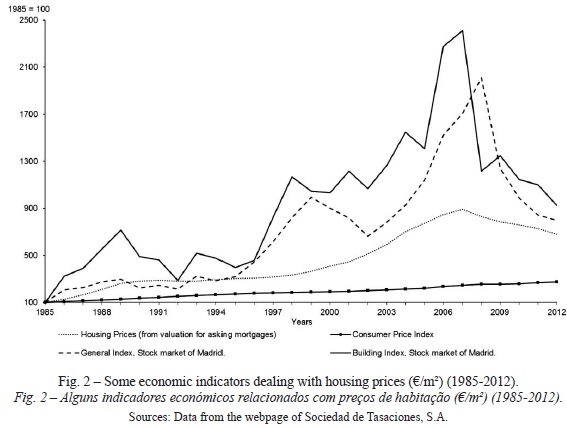

Some different indicators can explain the increase in house prices in recent years in Spain, and the subsequent slowdown or small decrease. Figure 2 shows the relationship between house prices according to national figures provided by the Ministry of Housing and the general stock market index, the building industry index and the Consumer Price index (CPi).

We can see how investors prefer to study areas more profitable than real estate. The building industry index decreased while the general stock market index increased until 2007 2008. The situation in 2009 until 2012 is completely different.

We can see how during the years when the stock market index decreased housing prices increased (e.g. 1989 1991). It is clear that house prices exceed the Consumer Price index (CPi). This fact has been observed in previous studies (Lázaro, 1995), that question whether the CPI is the right indicator for converting current prices into constant or nominal prices.

Unstoppable growth in the construction sector has been favoured by the fact that it has been an attractive and safe place to invest, especially during the years when stock market indexes were at their lowest. This, together with expectations for the revaluation of real estate has resulted in house prices being overvalued (ayuso and restoy, 2006b), and these steps are now being retraced. The increase in construction is both the cause and consequence of this phenomenon.

The higher rise in house prices in recent years not only in Spain, but also in the EU and in other countries as we have already seen, has led to considering causes other than those taken into account in previous periods of expansion, such as: a) the profitability of the property market as an alternative to other assets and investments, such as the stock market, because of the added value generated amongst other things, accounts for the increase in investor demand. Lower interest rates and more available mortgage products as well as tax exemption, credit facilities (Martínez and Maza, 2003) have made it easier to purchase a property (Whitehead, 2006). It increased demand, which the government has not curbed in spite of the existence of the sup prime mortgages. b) Credit market liberalization made interest rates go down with a natural shift in the demand and an increase in housing prices until the present economic crisis. it has been the object of some interesting models of debt (Fernandez Corugedo and Muelbauer, 2006) and other models such as Aron and Muellbauers (2006). Some authors state that 30% of this demand is from investors or speculators (Bellod, 2007) who want to make easy money, something that was impossible years ago. The international second home market also increased demand.

c) The rise in population which some authors reject as a direct cause (García Montalvo, 2007). it is a known, verified fact that there has been a greater increase in the housing stock than in the population. Indeed, if we take into account not only the overall population (natural growth and immigration which continued to increase until 2009) but also its residential mobility. The creation of new homes (immigration and a higher percentage of signalperson dwellings for reasons such as widowhood or separation), increased the demand for a second residence (from nationals, and also a growing number of retired foreign people). This demand may come closer to the number of dwellings built annually, though in all cases this occurs at a lower rate.

d) The introduction of the euro, which resulted in our applying the same price increase rate that already existed in many European countries (Rodríguez, 2006).

e) The lack of balance between the demands for an increase in housing has created a housing stock that is not being absorbed by population or by investors, unlike years ago, thus causing the sector to stagnate.

f) The increase in housing prices has meant that a percentage of the population may be excluded from buying. As housing is a basic necessity, like food, work, education, etc., effective housing policies (subsidised and/or social housing for those eligible, rent policy, etc.) are absolutely necessary to cater for such people. For this reason, royal Decree 801/2005, which regulates the state Housing scheme (20052008), was passed on 1st July in order to promote housing access for citizens. The current economic crisis may lead to an increase in the number of people excluded from being able to own a property, or those who cannot afford to make the mortgage repayments and have their property repossessed, or others forced to sell their property because they need cash.

For the moment we cannot say that housing prices have dropped to what some authors have referred to as a housing bubble, but that we are retracing our steps along the road towards overpricing and eventual stagnation, without knowing what the uncertain future of the economy will have in store for us.

3. The recent slowing down or stagnation in housing prices

From 2007 property valuation prices stagnated and 2009 saw a moderate decrease, which has not been stopped yet. There is not a universal model for explaining the facts; however, the household credit channel played an important part in the preceding boom, as well as in the crisis which began in the sub prime mortgage market.

Part of this recession came from the decline in housing prices in some countries from 2006, partly from the decline in demand of the international second home market and from the bank credit adjustment and credit crisis. All of these are the causes of the severe worldwide recession of 2008 2009. the present crisis began when loss of credit and non-payment of mortgages made evaluators more cautious. This is one reason for the clear decrease observed since 2008. Also, official statistics are not based on confirmed sale prices. the sources that appear in this graph (fig. 2) are mostly based on real estate values produced by valuation firms which are now very sensitive to the consequences of sub-prime mortgages.

To avoid a drop in prices that could exceed overvaluation in the sector, the housing stock must be reduced by slowing down the rate of building. This would result in a drastic reduction in construction. Less than half the dwellings started in 2001 were completed in 2008. This reduction trend has been continuous from 2009 up to now.

The reduction in the number of dwellings started and those completed is a clear indication of how the construction sector is slowing down and becoming stagnant. according to the Ministry of Housing data on the performance of the sector in the third quarter of 2008, prices on a national level decreased by 1.3% between July and September, which shows a slight annual increase of 0.7%.

This general tendency is not the same for autonomous communities, provinces or neighbourhood as we will see later. We can indicate some exceptions: Cantabria, Extremadura and La Rioja were the only autonomous communities that did not lower prices on a global level. However, some provinces have not only seen a decrease in prices, but also a slight increase in house prices from the first quarter of 2009, for example Caceres, Cuenca, León, Lugo, Orense, Palencia, Salamanca and Soria. These differences observed in the first quarter of 2010 and concealed by a global national figure, also exist on a municipal scale, so that the effect of the decrease in these global prices can be located in certain neighbourhoods and not the whole city.

What has happened to change this general trend, which until a few years ago, was undoubtedly on the increase? The answer is that the demand for housing can no longer keep up with the unstoppable increase in supply. The drop in properties being bought and sold is very much a reality. But, this demand is continuous for many town centre areas or city cores or in the city of the 19th century and early 20th century, in spite of the fact that buying a property now accounts for over 50% of the family budget (González, 2010). it has played a part in general terms, and also family income in Spain is starting to decrease as a result of unemployment. Fluctuations in interest rates have also affected the situation. We can therefore say that the economy, in general, and the housing sector in particular, are stagnant.

Attention must be paid to the economic crisis and behaviour of real estate. If, for example, the different kinds of interest rates increase or decrease (even by a small amount) or unemployment continues to increase or salaries to decrease, important changes could occur. The economic crisis has not been solved despite research by analysts and experts.

The loss of dynamism in the property sector is reflected in the decrease in the number of dwellings valued since 2007, according to Ministry of Housing data. This tendency can be seen throughout the EU, where construction has decreased in all countries since 2007, except in Poland and the Czech Republic. In spite of this, the importance of construction in the economy is still considerable. Almost 50 million people worked in construction related activities in the EU in 2008, which accounted for 7.6 % of total employment in the EU (IMF, 2008).

Prices are adjusted to the market in order to compensate for any possible loss in demand due to various reasons: a) the stagnation of the population, which cannot increase demand, although it is true that larger cities and provincial capitals are the last to lose population within the region; b) the latest figures say that the population is slowly decreasing again, and this does not mean that demand will increase; c) the possible increase in mortgage loan interest rates which then slows down; d) the recent reduction in wages in the public sector that can spread to the private sector.

Investors, who played a very important role in the demand for non subsided housing in Spain, have disappeared though on this occasion not as a result of the stock market competing with the property market, which has often occurred, but of the current crisis slowing down investment. The real state sector is not so profitable now as it was years ago and investors have more profitable places for their investments in other countries.

III. THE STUDY CASES: ALCALÁ DE HENARES AND LEóN

We are going to analyse what has occurred in two medium sized cities/ municipalities, Alcalá de Henares and León (fig. 3).

The former currently has over 200,000 inhabitants and the latter over 140,000. The division between neighbourhoods used in the case of Alcalá de Henares was that in the last nomenclature (institute of statistics of the Community of Madrid, available on internet), and in the case of León, a traditional historical division previously used in other publications (Gónzalez, 2000, 2002, 2005, 2006, 2011).

The population of both cities increased in the last decade, but in León it happened very slowly. Foreigners have been the key for the population increase in Alcalá de Henares in recent years. Alcalá de Henares is the municipality in the Community of Madrid with the highest number of foreign inhabitants after the municipality of Madrid: 20.66 per cent of the total population in 2009 while in 2009 the percentage for León municipality was 6.5 (González and Lázaro, 2012).

In both cities, the historic centre is in the inner city and has been renewed. It has a very important historical and artistic heritage. Thus, their prices are quite high, which is positive for the preservation of the district (Leichenco et al., 2001). Other city centres have increasing prices, as seen in the recent study on Marseille (Boulay, 2012).

1. Difficulties in obtaining real prices in second-hand housing: sources for the case study

We can obtain a general idea of the property market from official sources, either overvalued or undervalued prices, especially with regard to the aspect we are interested in: housing prices. The Ministry of Housing publishes quarterly data (previously provided by the Ministry for Public Works). There is a shortage of statistics for the property sector. In other countries such as the US, statistics are available on a monthly basis, whereas in Spain they are released every three months and are not totally reliable.

In Spain, official housing prices are calculated based on the weighted averages of valuation prices provided by different associations, which involves a number of problems including the fact that the composition of house quality in such a heterogeneous or segmented market as this is not taken into account (garcía Montalvo, 2007). Prices are based on valuation and not used in real transactions, which have other kinds of problems. Valuation prices depend partly on credit interest rates. There is a lack of information if we are looking for house prices for a district or neighbourhood. The official sources are not aware of prices in districts or neighbourhoods, and some particular districts or neighbourhoods are directly responsible for the slowdown in prices in the housing market. For this and other reasons, some authors say that official data are not reliable enough.

We can safely say that there are no sources for obtaining real house prices in Spain; these data are not available while valuations are more accessible. We will not go into problems related to the difficulty in obtaining market prices again, as they have been dealt with in previous publications (González and Lázaro, 2006). We can say that every financial transaction produces new prices, occasionally for the same real estate. furthermore, it is worth mentioning the segmentation of the housing market, the particular dynamics of housing entering and exiting the market, and the dynamics of supply and demand that sometimes make prices random depending on urgency, necessity or desire.

It is also difficult to obtain an accurate figure when establishing a single national value for the situation in Spain, given the distinct intensity of real estate activity in this country. This goes not only for the differences between cities, but also within the different city districts or neighbourhoods, as well as within the city districts themselves. Then an arithmetical mean of the municipality prices is not a complete index for studying prices.

There are differences between the different parts of the city: the town centre area or the old centre (historical city), or the 19th century city and the outlying or peripheral areas. In order to fulfil this aim we use the neighbourhood as a study unit.

Due to the lack of sources offering data according to neighbourhoods, we have created our own data base from property advertising by real estate agents in newspapers. This source has proven to be useful and worthy in studies about districts or neighbourhoods inside a city on repeated occasions (Leonard, 1983; González and Lázaro, 2006; Lázaro, 1995). There were a number of difficulties in creating and debugging the data base, which is very sensitive to the real situation of the property market. We can see how in times of prosperity property advertising proliferates and becomes tremendously repetitive, whereas in time of crisis, when property is not sold at the same rate as it is built, advertisements are restricted to cut costs.

For a better comparison between neighbourhoods, only advertisements for second hand and multifamily dwellings or blocks of flats were considered. single family dwellings were not considered in order not to distort reality in neighbourhoods where they are more predominant, as it is not always clear which percentage of the price corresponds to the house and which to the garden. We are aware that the quality of this type of housing can differ and that, generally speaking, the smaller they are the higher the cost of one square metre, as occurs with apartments. If we consider the segmentation of the housing market, we can confirm that the price of housing is neither unique nor objective (Lázaro, 1991). However, it is worth looking for an objective value, close to the possible market one, avoiding excessive fluctuations and searching for more or less exact approaches.

advertisements were taken from newspapers and magazines which have a great deal of property advertisements in each of the studied cities and also the newspapers considered as having a great number of readers in this field, which, in the case of Alcalá de Henares (Madrid) is the weekly magazine CaMBiHenares and in the case of León, the Diario de León. it is the only way to obtain housing prices because there are no official sources offering prices according to neighbourhoods or districts in these cities.

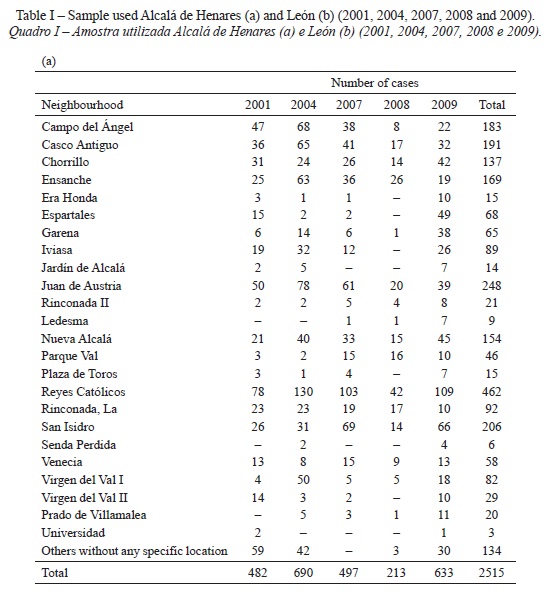

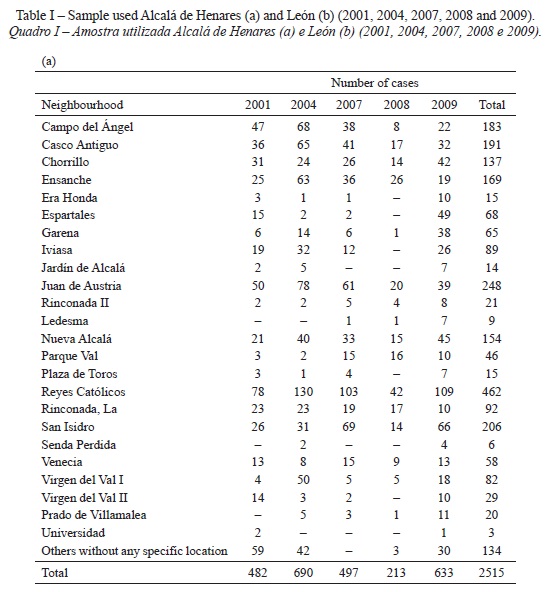

We took samples in the same period of time each year to make comparisons. Advertisements were always from the last four months (September to December) of 2001, 2004, 2007, 2008 and 2009 (Digital newspaper, 2011, real estate appraisal, 2011).

The only problem is that if we compare the same sample for each year, the number of both advertisers and advertisements has decreased substantially due to sector stagnation. The extra cost incurred by advertising in the press is a disadvantage for the seller of the property. This can be clearly seen in the case of the Diario de León, in which all the advertisements are paid for, but not in CAMBIHENARES where most of the advertisements are free. Reality tells us that there was no decrease in supply in 2008 in León in December of that year. There were lots of advertisements on the web while the Diario de León had fewer for this period. It is a fact that real estate advertisements have almost disappeared from newspapers while high numbers of advertisers were checked on different web sites that advertise property.

this shows the growing importance of internet in advertising property, as it is free of charge. The problem with the internet, as a source for obtaining property advertisements, is that web pages are updated in real time and it is not possible to refer back to previous facts. The continuity and homogeneity of the series constructed are only possible in real time. The new perspective of advertising property on the internet has thus opened up and solved the problem for obtaining data in the last term of 2009.

We have used a data base with almost 4,000 real estate advertisements, after debugging the corresponding data base. The difference between the two cities in the number of available advertisements each year clearly shows the dynamic of each city and its relative importance in population volume and weight in the real estate market. Alcalá shows greater real estate dynamism than León: it is a larger city and within one of the Spanish areas with a flourishing economy like the metropolitan area of Madrid.

Since the end of 2004 the same advertisements have been repeated, although estate agents have strategically attempted to advertise them differently, thus showing how difficult it is to sell a property. The beginning of the slowdown in the housing market can be seen with the decrease in the number of real estate advertisements. The sample used can be distributed as follows (table I).

The high number of properties advertised in the neighbourhood of Reyes Católicos in Alcalá de Henares or Crucero/Pinilla in León, is due to an improvement in the standard of living of their inhabitants who aspire to better housing in more desirable neighbourhoods in the city. It is also true that the Reyes Católicos area is considerably larger than many others, which also affects the observed situation. These unoccupied dwellings in the two neighbourhoods are bought by immigrants who have settled and own shops. Both have the highest number of immigrants of all districts in the municipality. There is also a large concentration of immigrants in the historic centres of both cities, which have become noisy leisure areas with tapas bars and the residents are moving to other quieter areas.

In the case of León, we do not have any advertisements for Las Labiadas as this neighbourhood is still under construction, and has now been stopped. We do not have enough cases to draw conclusions from neighbourhoods such as Puente Castro – a very consolidated area with very old single family dwellings, or La Lastra and san Pedro – which have recently been built.

2. Spatial differences in second-hand housing prices by districts or neighbourhoods

The study cases in two medium sized cities: Alcalá de Henares (Madrid) and León (Castile and León) will demonstrate the overall argument of this paper: how the general tendency in each city is not followed in all neighbourhoods and how recent construction promotes dispersal in the city at higher prices in neighbourhoods with new residential areas providing more single family homes.

The fact that neither the previous increase in house prices nor the subsequent slowdown affects neighbourhoods in cities in equal measure enables us to argue that the general situation in the sector is stagnant in several districts and has decreased in others. To analyse differences in prices between neighbourhoods we drew up a map for each city based on current prices obtained in 2001, 2004, 2007, 2008 and 2009. All the data were converted into constant prices for 2009 using the CPi (Consumer Price index) for 2006 of each of the corresponding provinces as a basis. We are aware that the CPi is based on the cost of a weeks shopping and that in Spain there is no index for the value of land or house prices (Lázaro, 1995). There is, however, a CPi for renting which has been discarded because house renting and selling behave differently, even antagonistically at times, whereas we believe that the general CPi is a better reflection of fluctuations in the economy, although it is not perfect.

Average prices are higher in Alcalá de Henares than in León. In the former case most property prices exceed 2000 /m², whilst in the latter, there are none that surpass 2500 /m². This could be due to the proximity of Madrid, which has increased demand in Alcalá, and also to relatively high prices in the metropolitan area.

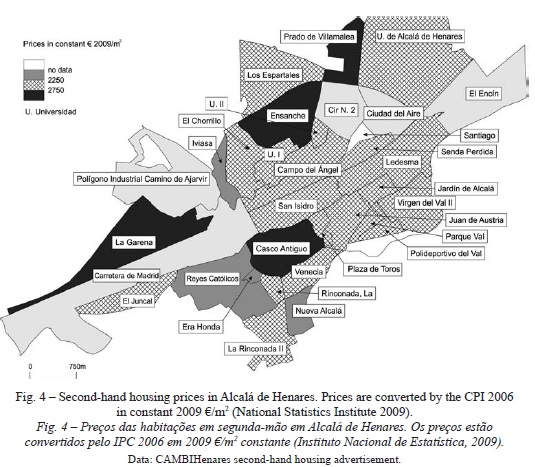

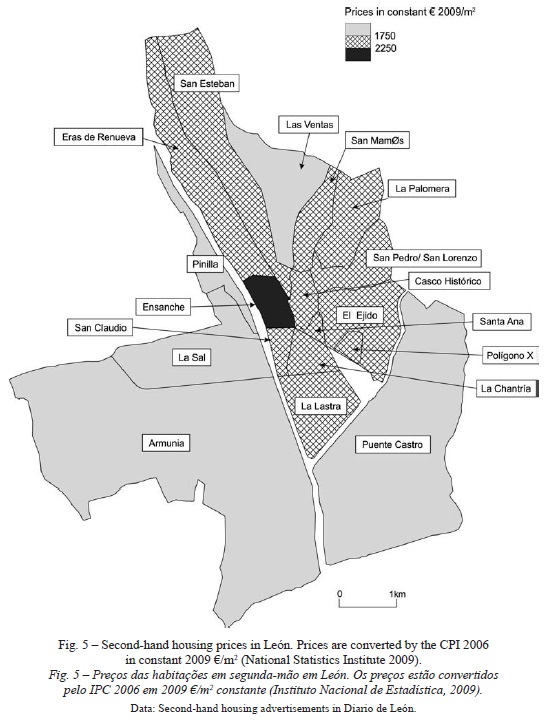

One result of our study is that Alcalá de Henares has higher prices than León. Three categories of second hand housing prices (high, medium and low) are distinguished on figures 4 and 5.

2.1. The highest prices within the cities (above 2750 /m² in Alcalá and above 2250 /m² in León)

The ancient city and the old University of Alcalá (Casco antiguo) which was designated World Heritage by UNESCO in 1998 and León Casco Histórico which was designated Conjunto Histórico artístico in 1964 (a national historic designation) have higher prices. it has already been demonstrated by nine US Texas cities that the official historic designation is associated with higher property values (Leichenko et al., 2001).

it is common to both cities that the expensive parts of the city are central town neighbourhoods, because they are centrally located and they have an historical value. In both cases, the price of land is higher in the centre. in Alcalá is the Casco antiguo neighbourhood (fig. 4) and in León is ensanche neighbourhood and Casco Histórico neighbourhood (fig. 5). However, in recent years, some historic areas of Casco Histórico in León have gradually deteriorated due to the presence of bars and leisure areas.

Very recently built areas or new neighbourhoods on the outskirts where construction has recently taken place, are also of better quality or desirable areas to live in, as shown on the maps of Alcalá (fig. 5) and León (fig. 5). The neighbourhoods with new housing have expensive dwellings (La Garena, Prado de Villamalea and el ensanche in Alcalá and eras de renueva, La Palomera, san Pedro/san Lorenzo and Santa Ana in León). The population look for new surroundings with quality, as has happened for example in eras de renueva in León or La garena and el ensanche in Alcalá de Henares. In some of these areas, prices increase because housing could initially be acquired at a more reasonable cost than in the centre, a possibility which has been eliminated by recent overvaluation and the current crisis. These new peripheral areas now have shopping malls and offices, thus promoting the modern multifunctional polycentral city model. Recently, more building work has been carried out in the latter neighbourhood. Oddly, these areas have a large number of single family dwellings. it was not a tradition for cities in Spain to build detached or semidetached dwellings until the 90s, in spite of few initiatives from the government called casas baratas (cheap houses), such as the garden City of Arturo Soria or few single family dwellings in specific neighbourhoods since the 1960s.

2.2. The medium prices within the cities (between 2251 and 2750 /m² in Alcalá and between 1751 and 2500 /m² in León)

Some of the prices of housing in Alcalá correspond to neighbourhoods near industrial areas (San Isidro, Ledesma and Rinconada ii) (fig. 4). These areas have been reassessed for housing, for example, the centrally located Poliseda and Perfumería GAL factories. This means a large number of new dwellings in the neighbourhood are on the market and their prices will not decrease as easily as neighbourhoods with second hand housing. Something similar has occurred in León in the Crucero area situated near the Bernesga river with the old sugar

The rest of neighbourhoods include a great variety of housing. Many of them are inside the city and have increased their buildings during the boom in construction that started in the middle of the 1960s, such as La Rinconada, Venecia, Plaza de toros, Juan de Austria. But there are some specific exceptions to this compact localization as espartales, which is a recently built up area; its mean price is not very high because it includes different zones: single family dwellings (very recent), blocks of dwellings (e.g. senda Perdida built in the 1980s, with great quality buildings, including swimming pools) and el Juncal is a border area initially destined to industry that currently has low quality buildings some of which are recent (fig. 4).

Most of the medium prices neighbourhood in León are the centrally located el ejido, La Chantría, Polígono X and La Lastra. La Chantría is one of the most overvalued neighbourhoods because it is close to the centre and a lot of new dwellings have been built there over the last 10 years. According to the sample taken, the high percentage of single family dwellings in el ejido and at the end of eras de renueva does not appear to have any particular effect on the price of land (fig. 5).

2.3. The lowest prices within the cities (below 2250 /m² in Alcalá and below 1750 /m² in León)

The presence of immigrants may not affect housing prices if they occupy deteriorated dwellings, as we have pointed out for central areas in León, or if conversely they are registered in the area where they work and inhabit quality dwellings or live in one of the most expensive neighbourhoods, or perhaps are comfortably off and have bought a dwelling. this aspect and its importance could be the object of an independent study which we do not consider to be a factor affecting differences in neighbourhoods housing prices. the popular neighbourhoods with a low income in Alcalá have low prices: reyes Católicos, era Honda, nueva Alcalá and iviasa. Reyes Católicos has a much deteriorated area call Puerta de Madrid with people relocated from shanty towns and slums. it is the neighbourhood with the biggest number of immigrants in Alcalá, more than 9,000 many of them from Africa (fig. 4).

The cheapest neighbourhoods in León are furthest from the centre: Las Ventas, La sal La Vega, armunia and Puente Castro (fig. 5. Despite revaluation, Armunia and Las Ventas have very low starting prices in the city, as traditionally, they were shanty towns inhabited by construction and railway workers and a lot of subsidised housing was built there. Also, the average size of the dwellings in these neighbourhoods is the smallest in the city.

Over 10,000 immigrants currently live in the municipality, mostly in dilapidated flats in central neighbourhoods. this explains the decrease in prices in the historic city centre where there is a considerable amount of dilapidated housing. There are no immigrants in the surrounding villages and rural areas that are dependent on León. Africans live in el Crucero and La Sal, which has a large colony of Moroccans, and Latin Americans in Las Ventas (fig. 5) (Romero, 2008; González and Lázaro, 2009). Other sources as the Valuation society Market studies confirm this trend in prices according to neighbourhoods. Prices are higher in more central areas.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

Years ago the situation of the stock exchange made the real estate market a refuge sector for investors. The housing wealth effect on consumer expenditure works via the credit channel (Muellbauer, 2009, 2010) and this caused a rise in dwelling prices. Nowadays the fall of the stock exchange, the indebtedness of families and increase in unemployment has made second hand housing prices stagnate and decrease. We observe a situation that could be classified as stagnant since prices have not fallen below 2001 levels. While official sources point to a national tendency of dropping prices, we have seen different price fluctuations within neighbourhoods. After 2009, prices in city centres decreased more slowly or are stagnant, whereas prices of housing in new suburbs decrease rapidly after overvaluation in preceding years in the two study cases.

However, we cannot definitely say that second hand prices have dropped as drastically as stated by the official available statistics, as the real estate market is greatly segmented. There are isolated cases of individuals who need to sell their property urgently, or those who cannot meet mortgage repayments with the result that the bank takes over the property. In these specific cases the price dropped, but prices have not decreased in the same way in all neighbourhoods. the price of a second hand dwelling is not only higher in the town centre but also in recently built peripheral areas (suburbs) where housing is revalued because of the initial possibility of acquiring good quality property at a more reasonable price, thus causing overvaluation to accelerate in these neighbourhoods. Price behaviour in these two types of area is different in both cities. Second hand dwelling prices are always higher in Alcalá de Henares than in León town because Alcalá is impacted by the proximity of Madrid.

Areas where prices were traditionally higher, for example the historical centre in the two cases, have not been affected by the price decrease because of their central location or high quality. These areas were not overpriced years ago in the same way as the city suburbs on the outskirts. So, today these central dwelling prices have not dropped in Alcalá and León, as has occurred in many suburb locations.

Some neighbourhoods in both towns, especially where housing was overpriced, have suffered a drastic decrease in price as a result of the economic crisis currently affecting the country. We can see how the relative importance of this decrease in some neighbourhoods, which were often overvalued, generally causes a drop in housing prices. Today, the main cause of the stagnant second hand housing market is the lack of bank credit facilities.

We do not dare to suggest what will happen in the future, because the situation has been made more complicated with Spain having the highest unemployment rates in Europe, but we continue to assume that there are considerable differences between neighbourhoods. some foreigners investing in many quality neighbourhoods are looking for a good opportunity to buy a cheap dwelling. Perhaps this recent demand is preventing prices from dropping in many neighbourhoods such as Alcalá de Henares and León.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would especially like to thank Dra. María ángeles Díaz Muñoz for her participation in the research project and Dra. María Jesús Salado for her help in GIS shapes.

Data for this paper were obtained as part of the research project BsO200202432 with the financial support by the Spanish Ministry of science and technology and the research project eVK42001 00171 of the V framework Program of r&D.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arestis P, Mooslechner P, Wagner K (2009) Housing market challenges in Europe and the United States. Economics & finance Collection 2010. CY Basingstoke sn: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Aron J, Muellbauer J (2006) Housing wealth, credit conditions and consumption. Oxford: mimeo, nuffield College. [ Links ]

Aron J, Duca JV, Muellbauer J, Murata K, Murphy a (2010) Credit, housing collateral and consumption: evidence from the UK, Japan and the US department of economics. Discussion Paper, series 487.

Ayuso J, Blanco R, Restoy F (2006) House prices and real interest rates in Spain. Documentos de trabajo, nº 0608. Banco de España.

Ayuso J, Restoy F (2006a) el precio de la vivienda en España : ¿es robusta la evidencia de sobre-valoración? Boletín Económico, Banco de España, 6: 57 65.

Ayuso J, Restoy F (2006b) House prices and rents: an equilibrium asset pricing approach. Journal of Empirical Finance, 13: 371 388. [ Links ]

Bellod Redondo JF (2007) Crecimiento y especulación inmobiliaria en la economía española. Estudios de Economía Política, 8:59 82. [ Links ]

Boulay G (2012) real estate market and urban transformations: spatiotemporal analysis of house price increase in the centre of Marseille (1996 2010). Journal of Urban Research [Online], 9.

Browning M, Gortz M, LethPetersen S (2009) House prices and consumption: a micro study. Unpublished manuscript. Oxford University, Oxford.

Cameron C, Muellbauer J, Murphy a (2006) Was there a British house price bubble? evidence from a regional Panel. Department of economics. Discussion paper series, 276: 1 45.

Chen Z, Cho Sh, Poudyal N, Roberts Rk (2009) forecasting housing prices under different market segmentation assumptions. Urban Studies, 46(1): 167 187. [ Links ]

Fernandez Corugedo F, Muelbauer J (2006) Consumer credit conditions in the UK. Bank of England. Working Paper, 314: 1 62. [ Links ]

GarcíaMontalvo J (2007) algunas consideraciones sobre el problema de la vivienda en España (some considerations on the problem of housing in Spain). Papeles de Economía Española, 113:138 155. [ Links ]

García Montalvo J (2006) reconstruyendo la burbuja: expectativa de revalorización y precio de la vivienda en España Papeles de Economía Española, 109: 44 75. [ Links ]

García Palomares JC, Gutiérrez Puebla J (2007) La ciudad dispersa: cambios recientes en los espacios residenciales de la Comunidad de Madrid. Anales de Geografía de la Universidad Complutense, 27(1): 45 67. [ Links ]

Galster George G, Tatian P (2009) Modeling housing appreciation dynamics in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 29: 722. [ Links ]

González González M J (2011) El pensamiento estratégico como motor de la gestión de cambio en el territorio (strategicthought as anengine of changemanagement in territory). Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 55:211230. [ Links ]

González González M J (2010) the changing structure of households and families, and its impact on health in Spain. Finisterra – Revista Portuguesa de Geografia, XLIV(89): 922. [ Links ]

González González M J (2005) El desarrollo económico sostenible de los centros históricos. Ería, 68: 365272.

González González M J (2002) La ciudad sostenible. Planificación y teoría de sistemas. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles,

33: 93103. [ Links ]

González González M J (2000) estructura residencial y organización del espacio en la ciudad de León Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 29: 109 130. [ Links ]

González González M J, Lázaro Torres M L (2012) La distribución espacial de la población inmigrante en dos ciudades medias: Alcalá de Henares y León y su relación con los precios de la vivienda. Anales de Geografía de la Universidad Complutense, 32 (2): 275 295. [ Links ]

http://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/agUC/article/view/39721/38212. [Accessed 7 September 2011].

González González M J, Lázaro Torres M L (2009) La inmigración reciente en España : su contribución al crecimiento demográfico y a la economía. Boletín de la Real Sociedad Geográfica, CLXV: 183 2002. [ Links ]

González González M J, Lázaro Torres ML (2006) the trends towards the increase in housing prices in Spain. the scope of reinterpreting urban areas. In igU, Urban changes in different scales: systems and structures. Universidad de Santiago de Compostela/IGU Commission on monitoring cities of tomorrow, Santiago: 149 161.

Instituto de Estadística de Madrid. Nomenclator 2008 (Census 2008) División de barrios en Alcalá de Henares. http://www.madrid.org/iestadis/fijas/estructu/general/territorio/nomenmunicipios.htm [Accessed 7 September 2011]. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística: national statistical institute data base. http://www.ine.es [Accessed 7 September 2010].

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2008) World economic outlook. Housing and the business cycle. International Monetary, Washington: IMF.

Lamoth e Fernández P, de Luna W (2006) La inversión inmobiliaria. Criterios de valoración y panorámica en España (real estate investment. Evaluation criteria and planning). Papeles de Economía Española, 109: 140154. [ Links ]

Lázaro Torres M L (1995) últimas tendencias en el precio de la vivienda en la ciudad de Málaga (1981 1984) (recent trends in the price of housing in the city of Malaga, 1981 1984) Anales de Geografía de la Universidad Complutense, 15: 421433. [ Links ]

Lázaro Torres M L (1991) La validez de los anuncios del diario sur para el estudio del precio de la vivienda en Málaga (1937 1980) Estudios Geográficos, 205: 653671. [ Links ]

Leichenko R M, Coulson N E, Listokin D (2001) Cities historic preservation and residential property values: an analysis of texas. Urban Studies, 38(11): 1973 1987. [ Links ]

Leirado Campo L (2006) Mercado de la vivienda. Evolución reciente: una visión del estado de la cuestión Papeles de Economía Española,109: 107124. [ Links ]

Leonard G (1983) Les annonces immobilières à angers. Norois , 117(1):111 118. [ Links ]

Martínez Pagés J, Maza La (2003) análisis del precio de la vivienda en España . Documentos de trabajo del Banco de España, 7: 748.

Martínez D, Riestra T, San Martín i (2006) La demanda de vivienda, factores demográficos Papeles de Economía Española, 109: 91 [ Links ]106.

Meen G (2001) Modelling spatial housing markets: theory, analysis and policy. Advances in Urban and Regional Economics. Boston: Kluwer academic Publishers, vol. 2. [ Links ]

Menéndez Rexach A (2006) Los objetivos económicos de la regulación del suelo: evolución de la legislación española y perspectivas de reforma Papeles de Economía Española, 109: 257 272. [ Links ]

Ministerio de la Vivienda statistics (Ministry of Housing). http://www.mviv.es/es/index.php?option=com_content&task=blogsection&id=9&itemid=35 [Accessed 7 September 2011]

MuellbauerJ (2010) Household decisions, credit markets and the macroeconomy: implications for the design of central bank models. Bank for international settlements working paper 306, [ Links ] March 2010. http://www.bis.org/publ/work306.htm [accessed 7 september 2011]

Muellbauer J, Murata K (2010) Consumption, land prices and the monetary transmission mechanism in Japan. In Hamada K, Kashyap a K,

Weinstein D (eds.) Japans bubble, deflation and long-term stagnation.Cambridge: Mit Press: 143. [ Links ]

Muellbauer J, Murphy A (2008) Housing markets and the economy: the assessment. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24(1): 133. [ Links ]

OeCD (2005) recent house price developments: the role of fundamental. OECD Economic Outlook, 78: 193234. [ Links ]

Rodríguez López J (2006) Los booms inmobiliarios en España. Un análisis de tres periodos Papeles de Economía Española, 109: 76 90. [ Links ]

Romero M (2008) La inmigración va por barrios (Immigration by neighbourhood).In Diario de León, 27th November: 2.

Slacalek J (2009) What drives personal consumption? the role of housing and financial wealth. B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, Berkeley Electronic Press, 9(1): 135. [ Links ]

Sociedad de Tasación, S.A. (TINSA) (taxation society) http://web.sttasacion.es/html/menu6.php [Accessed 7 September 2011].

Sociedad de Tasación, s.a. (2010) Síntesis del estudio de mercado de vivienda nueva en Julio de 2010. Boletín de Mercado Inmobilario, págs. 21.

Whitehead ChMe (2006) Una perspectiva internacional de los mercados de la vivienda Papeles de Economía Española, 109: 213. [ Links ]

Recebido: Julho 2012. Aceite: Junho 2013.