Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.96 Lisboa jun. 2013

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Gentrification, residential ethnicization and the social production of fragmented space in two multi-ethnic neighbourhoods of Lisbon and Bilbao

Nobilitação urbana, etnicização e fragmentação sócio-espacial em dois bairros multi-étnicos: Lisboa e Bilbau

Jorge Malheiros1; Rui Carvalho2; Luís Mendes2

1Associate Professor at the IGOT and researcher at the CEG of the University of Lisbon. E-mail: ogatomaltes@zonmail.pt

2 Researcher at the CEG of the IGOT, University of Lisbon. E-mail: racarvalho@fl.ul.pt; luis.mendes@ceg.ul.pt

ABSTRACT Simultaneous trends for ethnicization and gentrification are contributing to the fragmentation of contemporary urban spaces. This is characterised by the emergence of new social and urban units that break the homogeneity of the modern city and lead to the development of new networks, territorially discontinuous, less neighbourhood centred and with a limited intersection. With Mouraria (Lisbon, Portugal) and San Francisco (Bilbao, Spain), two traditional and multiethnic neighbourhoods, as case-studies this paper aims to critically discuss the nature of gentrification, its coexistence with ethnicization and its contribution for socio-urban fragmentation. The empirical analysis of the residents social networks will be used to test levels and types of interaction and the spatial formats they assume. Keywords: Gentrification, ethnicization, sociospatial fragmentation, social networks.

RESUMO

sócio-espacial em dois bairros multi-étnicos: Lisboa e Bilbau. Tendências simultâneas para a etnicização residencial e a nobilitação têm contribuído para a fragmentação do espaço urbano contemporâneo. Esta caracteriza-se pelo surgimento de novas unidades sociais e urbanas que quebram a homogeneidade da cidade moderna e conduzem ao desenvolvimento de novas redes relacionais, descontínuas, menos centradas no bairro e com um nível limitado de intersecção. Com a Mouraria (Lisboa, Portugal) e San Francisco (Bilbau, Espanha), dois bairros tradicionais e multiétnicos, como estudos de caso, discutir-se-á criticamente a natureza da nobilitação, a sua relação com a etnicização e a sua contribuição para a fragmentação sócio-espacial. A análise das redes sociais dos residentes será utilizada para testar níveis e tipos de interacção, bem como os formatos espaciais que estes assumem.

Palavras-chave: Nobilitação urbana, etnicização, fragmentação sócio-espacial, redes sociais.RÉSUMÉ

Gentrification, ethnicization et la production sociale de lespace fragmenté dans deux quartiers multi-ethniques de Lisbonne et Bilbao. Des tendances simultanées déthnicization et de gentrification ont contribué à la fragmentation de lespace urbain contemporain. Celle-ci est caractérisée par de nouvelles unités sociales et urbaines, qui détruisent lhomogénéité de la ville moderne et conduisent au développement de nouveaux réseaux, spatialement discontinus, moins centrés sur les quartiers et avec une intersection limitée. A partir de deux études de cas de quartiers traditionnels et multi-ethniques (Mouraria, Lisbonne et Bilbao, Espagne), la nature de la gentrification sera discutée, ainsi que sa relation avec léthnicization et sa contribution pour la fragmentation socio-spatiale. Lanalyse empirique des réseaux sociaux des résidents servira pour tester les niveaux et les types dintégration, ainsi que leurs formats spatiaux.

Mots-clés: Gentrification, ethnicization, fragmentation socio-spatiale, réseaux sociaux.

I. INTRODUCTION

The debate about the urban gentrification process is often intertwined with the issue of socio-spatial fragmentation, both embedded in the principle of uncertainty that literature associates to post-modern city development. Actually, this idea of uncertainty is one of the key elements to understand the so-called post-modern geographies of gentrification and its effects in the social production of a fragmented urban space (Mendes, 2011). First, because the simultaneous unbalanced processes of suburban expansion – dominant in the neoliberal version of 1980s-1990s Iberian capitalist model (Malheiros, 2012) – and piecemeal urban city centre rehabilitation are producing contradictory movements of urban deconcentration (dominant but decaying) and urban recentralization (limited but with a higher potential increase). Second, because gentrification contributes to break the continuity of social and urban elements present in the modern city. On the one hand, real estate projects targeting gentrifiers often have a punctual nature, contrasting with the surrounding built environment and leading to forms of micro-scale segregation, substantially different from the functional zoning and the homogeneous social areas of the industrial and modernist city. On the other hand, the social class and the social practices of the gentrifiers are usually different from the ones of former established lower class residents of the rehabilitated inner city or working class districts. This leads to a third issue related with the specific networking and appropriation strategies of gentrifiers. Actually, these tend to develop specific spatial appropriation strategies characterised by discontinuity and multi-scaling, that are less-neighbourhood centred and may involve, daily or weekly, different parts of the metropolitan area, other regions of the country and even distant countries.

Similarly to what happened in other cities of advanced capitalist societies, Lisbon and especially Bilbaos old industrial (e.g. East docklands of Olivais in Lisbon; Nervion river banks in Bilbao) and central areas experienced important regeneration processes that had an impact on the urban and the social fabrics of both cities. In addition, Lisbon and Bilbaos inner-city housing markets have changed significantly throughout last decades, namely due to the emergence of new housing products and formats that have contributed to generate a phenomenon of gentrification. Finally, along the 1990s and the first half of the 2000s, both cities experienced a significant inflow of labour immigrants coming from non-EU countries, that were crucial to bridge the pre-2008 crisis labour market gaps in sectors such as construction and public works, petty commerce, cleaning and care. Because gentrification processes are usually stepwise, the first gentrifiers, often classified as marginal gentrifiers (Rose, 1984), set up in areas that are still characterised by signs of physical decay, relatively low rents and the prevalence of declining lower classes and ageing population. This picture of the early gentrification areas points to a social atmosphere and to a housing market offer that are suitable for immigrants searching for relatively cheap rental market houses (more present in the inner city than in peripheries) – often in need of some repairs – and for central locations that enable a good access to public transport. Therefore, some neighbourhoods that start to experience gentrification simultaneously experience a process of ethnicization; this combination leads to an increasing complexity of fragmentation processes that may involve simultaneous ethnic and social micro-scale segregation, as well as the development of inter-crossing and overlapping webs of social relations. With Mouraria (Lisbon) and San Francisco (Bilbao) – two traditional and multiethnic neighbourhoods – as case-studies, this paper will focus on gentrification processes (socially selective recentring in the citys central areas) taking place in inner city spaces that are simultaneously experiencing ethnicization due to the residential settlement of non-EU immigrants. Both these aspects are contributing to social and residential fragmentation. Empirical data referring to these individuals social features and networks will be used with the purpose of demonstrating the emergence of socio-spatial discontinuities and especially the development of complex, fragmented and differentiated social relations. Following the previous results, a discussion on the mutual influence between gentrification and social and ethnic mixing will be presented, trying to bring further evidence on the real inductive effects of social/ethnic mix on gentrification, whilst prospectively warning about possible future impacts of this last phenomenon on these neighbourhoods sustainability as relatively low-cost housing immigrant reception areas.II. SOCIOSPATIAL CHANGES IN FRAGMENTED METROPOLISES: INNER CITIES ETHNICIZATION AND GENTRIFICATION

Since the 1980s, the housing market of many Southern European cities, similarly to those of advanced capitalism, has suffered significant changes, with the appearance of new housing products and new housing formats, with consequences for the urban spatial organization of those cities (Mendes, 2008; Rodrigues, 2010). In fact, according to several authors, these changes have been outlining a tendency of recentralization that, although minor in comparison to peripheralization and the suburban expansion process, has started to show an impact on several historical and inner city neighbourhoods, thus contributing to introduce modifications on both their urban and socioeconomic features.

Despite their condition of being a repository of rooted and old manifestations and cultural traditions, both the studied neighbourhoods – Mouraria (Lisbon) and San Francisco (Bilbao) – seem to be examples of those social and spatial contexts: they have, in the past few years, faced important changes concerning their social fabric with the arrival of new dwellers with a social and a cultural background and also with a lifestyle distinct from the established ones. It is within this framework that the concept of gentrification appears as a process through which some groups have become central to the city, at the same time as they were turning that city into a central place for themselves. They have done so not only from the point of view of a privileged residential location, but also of its usage, especially its appropriation as a mark of social centrality (lent by territorial centrality), by the symbolic power it gives and by the social distinction it allows. We refer, in particular, to the so-called new middle classes (Butler, 1997; Ley, 1994, 1996), the main agents of a recentralization movement that rediscover in the historical and/or architectural value of neighbourhoods the capacity to reinvent themselves, both at a social and a cultural level. The citys old neighbourhoods have been understood until recently as obsolete, non-updated, non-practical, and incapable of guaranteeing acceptable life conditions under contemporary patterns. However, adequate answers addressed by these groups have been appearing, triggering a phenomenon of marginal gentrification. This refers to the fact that a group of (mostly young) people with fairly low economic capital but with a relatively high social and cultural one, normally with high skills but often employed in precarious jobs, comprehending students, artists, social workers and activists, as well as members of some stigmatised social groups such as single mothers and homosexuals, become pioneer gentrifiers attracted to inner city neighbourhoods. They tend to arrive in the neighbourhoods in earlier stages of urban and social transformation, benefitting from relatively low real estate prices, in pursuit of a nonconformist lifestyle and socially mixed environment, thus refusing suburbias normative and conventional way of life. Gentrification occurs in various ways in different neighbourhoods of different cities, comprising diverse trajectories of neighbourhood change and implying a variety of protagonists (Lees, 2000). However, the discussion over the past 40 years on the concepts definition is relatively clear. Hence, the concept of gentrification has been defined as the conversion of socially marginal and working class areas of the central city to middle-class residential use (Zukin, 1987: 129). Clay (1979) developed one of the first stage models of gentrification, where he outlined a schema from stage 1 (pioneer gentrification) to stage 4 (maturing gentrification). Typically, gentrification is initiated by a few households in search of urban niches in run-down neighbourhoods which provide spaces for alternative lifestyles (for example, avant-garde artists, gay and lesbian communities). Subsequent stages increasingly involve wealthier middle-class households and real-estate developers who capitalise on the rent gap or potential increase in value in these neighbourhoods by buying up and renovating dwellings, and reselling them to more affluent members of the new middle class (Smith, 1996). Through this process, the displacement of both old-established and new-wave occupants, that may also involve immigrants that benefitted from relatively low prices, that characterise the pioneer gentrification stage, takes place. This is a stylised representation of course – the stages can change in order and not every gentrifying place goes through all stages. For example, some areas in Bilbao may have tended to fast-forward on some of these stages as the outcome of policy-oriented urban regeneration programs and the so-called Guggenheim effect (Vicario and Martinez Monje, 2005). Marginal gentrifiers, which appear to be the dominant ones in Mouraria (Malheiros et al., 2012) and, as will be seen ahead, are also important in San Francisco (Bilbao), com-pose the pioneer people, a small group of avant-garde bohemians, risk-oblivious people that move in and renovate properties for their own use. They are usually renters who mix in easily with the existing population. At this stage, there is not a lot of change to the building stock and no displacement. In time, gentrifiers that are less economically marginal than these marginal gentrifiers may appear, many of whom are often in a position to buy or rent for a higher price. If in the first stages we only see small-scale home renovations by first renters and home-buyers (Rodrigues, 2010), more advanced ones tend to imply deeper rehabilitation processes that may involve public support, namely interventions in the public space. From the social point of view, urban rehabilitation may progressively lead to a change in population, owing to the fact that the former resi-dents, who very often are part of less-privileged strata of society, find themselves gradually being replaced by people coming from the upper-middle and upper classes who are able to pay for the restored houses. By definition, gentrification is always a process of upward social filtering. It means socially recomposing (and replacing) inner-city and run-down areas and transforming them into medium-upper class quarters in a process we are forced to call social replacement or filtering up whereby the resulting socio-spatial segregation is strengthened and the social division of the urban space is deepened. The truth is that the appropriation of space characteristic of gentrification, introduces changes in the scale of socio-residential segregation. Generally, the fragmentation of space should be understood as a spatial organisation characterised by the existence of distinct spatial enclaves that are not contiguous with the socio-spatial structure surrounding them (Barata Salgueiro, 1998: 225). This author also points out that what she defines as an enclave is not that much so by its size (which can be small) but instead for the kind of relationship (or better, non-relationship) it has with surrounding areas that adjoin it in spatial terms, which may be dispossessed of a social and functional continuity. The process of gentrification that occurs in the centre of various metropolises in the advanced capitalist world thus seems to corroborate the thesis put forward by Barata Salgueiro (1997, 1998, 1999, 2006), where she posits the idea of the post-modern city as a fragmented space. Incomplete processes of population transition, such as the classical filtering down that is characterised by the substitution of the original resident population of central neighbourhoods by less affluent groups, often with other ethnic origins, also contributes to fragmentation. Actually, if the original filtering down hypothesis assumes that total (or almost total) replacement of the original population takes place, nowadays the idea of population substitution can be replaced by residential ethnic mix because the simultaneity of processes such as gentrification and ethnicization bring to the neighbourhoods new residents with different social and ethnic backgrounds. In addition, impacts upon local real estate markets and increasing property prices due to the development of the gentrification process (with piecemeal rehabilitation of buildings) and, eventually, to planned public interventions in the public space, harden the access of lower classes and poor immigrants to some quarters, thus strengthening the fragmentation effect. All in all, the compact city with its well-defined boundaries and a relatively social homogeneity in its centre has been shattered into a set of distinct fragments where the effects of mobility, rehabilitation, contradictory real estate speculationi and urban legislation have given way to more complicated territorial arrangements that are spatially disconnected and socially more enclosed (Dematteis, 2001; Graham and Marvin, 2001). Real estate projects built with gentrification in mind have an island-like point quality about them and cause a brusque difference when compared with the social make up around them. The urban structure promoting them is characterised by enclaves in dissonance with the mostly homogeneous socio-spatial composition of their surroundings. We could say that although a spatial contiguity exists there is no social or functional continuity, the close neighbourhood having lost its relational and practical propinquity owing to the fact that new neighbours and the activities they pursue are increasingly carried out in outward networks of relations. Each new resident builds up his networks of transversal social connections with several residential spaces so that the strong links based on local solidarity and friendship now tend to surpass the geography delimiting the quarter. In the post-industrial city, there is a gradual loss of importance with what regards the next door factor in structuring social relationships. In fact, the next has ceased to be the same. Social relations among new neighbours are less likely to focus upon the space occupied by the quarter and the close neighbours. Each individual may arrange his own way of establishing a relationship close at hand and a relationship further away, resorting to a profuse variety of relationships in much diversified social circles (Remy, 2002; Navez-Bouchanine, 2002; Carmo, 2006). And this is particularly meaningful among immigrants and gentrifiers. This converges to the need to understand the social micro-units, the spaces containing restricted groups and the complex social dynamics, mainly in terms of noting a considerable heterogeneity of spatial, social and cultural behaviours, which do not easily fall into a single classification of well-defined social classes and especially in a clear spatial mosaic of highly homogeneous social fragments, such as those associated to the industrial (and modern) city since the earlier studies of Engels (1971 [1844]). Undoubtedly, nowadays the urban social space of gentrification and ethnici-zation has taken the shape of an intricate network; it is not so much dependent on immediate neighbouring spaces as it is on a cross-spatial and, not infrequently, a cross-border rationale. Precisely speaking, both rationales represent the citys integration in the march towards economic and cultural globalisation (Butler and Robson, 2001a, 2001b). Nevertheless, it would not be consistent to argue that the rationale of the social appropriation of space in a typically Fordist city has now been completely overtaken. For this to be so the space-time rationale based on spatial contiguity and on the functional and social continuity of each urban sector would have completely disappeared, which is not true. Nevertheless, by recognising the existence of complex and synchronised workings of different socio-spatial rationales, even in smaller spaces such as the neighbourhood-space within metropolitan areas, one is obliged to review the concept of social space anew, and if needed be, preferentially resort to carrying out micro-scale (e.g. at the intra-neighbourhood level) studies.III. CREATING BRIDGES IN A FRAGMENTED SPACE? GENTRIFICATION, DIVERSITY AND SOCIAL MIXING IN THE INNER CITY

Tolerance and diversity are not new topics in gentrification research. Sociocultural diversity has often been viewed as one of the most relevant amenities of living in dense cities (and, particularly, in their central areas) by creating an ambience that is considered by gentrifiers to be highly stimulating (Lees, 2008). Following the seminal work of Caulfield (1994) – which framed gentrification as a critical, counter-cultural and emancipatory process – Ley (1996) and Butler (1997) posit the existence of what they coin as a new middle class, one able to exploit the redemptive potential of the inner-city, through the expression of more liberal and socially inclusive, and thus less instrumentalist and conservative, ideologies and practices (Ley and Mills, 1986).

Furthermore, the problematic of social mixing has also recently moved to the forefront of the gentrification debate. In part, this has been enthused by neoliberal urban policies promoting social mix (Bridge et al., 2012) and because there is a poor evidence base for the widespread policy assumption that gentrification will help increase and foster social mixing, thereby surging the social cohesion of inner city communities. Prominently, the works of Rose (2004) and Davidson (2010) show that little evidence has been found for substantial interactions between populations and for shared perceptions of community after gentrification has occurred. Referring specifically to new-build gentrification this last author claims that this phenomenon has even contributed to generate a socially tectonic situation, with clear impacts on the enhancement of micro-scale segregation and on the social and residential fragmentation of contemporary urban spaces. There has been a number of studies of social interaction in restructured quarters and these have found that social networks amongst neighbours tend to be socially segregated, especially in terms of socioeconomic status and ethnicity (Musterd and Andersson, 2005; Arbaci and Rae, 2012). An influx of middleclass residents into an inner-city neighbourhood, rather than acting as a catalyst for social cohesion, tends to lead to greater superficiality and even to hostile relations amongst neighbours. In spite of their desire for diversity and difference, new middle classes tend to self-segregate. Notions of diversity appear to be more in the minds of these gentrifiers rather than in their actions, reflecting the way in which they define them-selves: as a specific class fraction and, in particular, as cosmopolitan citizens. There seems to be no or very limited transference of social capital from high to low-income groups, nor any of the other desired outcomes from the introduction of a middle-class population into these central-city locations (Lees, 2008; Davidson, 2010). In part this is due to the transitory nature of the new residents and to the spatially segregated nature of the new-build developments with respect to the adjacent low income communities. These different populations (established residents, immigrants, gentrifiers ) do not work in the same places, nor use the same means of transport. They do not frequent the same restaurants or the same public spaces. According to David-son (2010), the coexisting inner city groups have different household structures and different expectations and aspirations about community and mixing. His empirical work on the social relations of both incoming gentrifiers and long-term residents of several new-build areas (and adjacent neighbourhoods) in central London proved that social ties seldom crossed class and racial boundaries. He also found the existence of frequent clashes between the norms of gentrifiers and those of longer-term residents. Recurring back to the gentrification stage model proposed by Clay (1979) one should add that the impacts portrayed by different groups of gentrifiers on neighbourhood social capital and cohesion appear to be differential. For example, pioneer gentrifiers desired social mixing, whereas secondand especially third-wave gentrifiers tend to be more individualistic. Hence, pioneer gentrification appears to have less negative aspects associated with it than that of later waves. Rose (1984) also advised for the importance of setting a distinction between marginal and mains-tream gentrification, the former referring mainly to marginally employed individuals (noticeably women, students, artists, young couples or single parents) in pursuit of a socially mixed environment. Also, Van Criekingen and Decroly (2003) portray the marginal gentrifiers as individuals that are wealthier in cultural capital than in economic capital. In line with this last work, several references have been made in the gentrification literature to the linkage between material and cultural capital, mostly drawing on Bourdieus ideas (Bridge, 2001). Because early gentrifiers are seen as having large amounts of cultural capital and limited stores of material capital, the former one seems to be deployed to achieve distinction, particularly through the mobilization of a set of values that privilege pro-urban lifestyles. According to these accounts gentrification is seen as a strategy of distinction for an emerging new middle class. This is in line with what Alain Bourdin (1979, 1980, 1984) is talking about when he advances the expression reinvention of the patrimony to refer to the return to the historical centres by certain social groups and political interests. According to this line of thinking, gentrification has become associated with a culture of consumption, with the aestheticization of social life and also with a movement for patrimonialization, the latter one involved in discourses and practices that value the physical and symbolic remnants of the past extant in those inner-city areas (Mendes, 2008). This last process includes the reinvention of a sense of community and group cohesion, beheld by the gentrifiers as instrumental for the recovery of the identity of those historical neighbourhoods. In a superficial view one might assume this patrimonialization movement as a (postmodern) reaction to the disappearance of traditional lifestyles and to a prevailing hedonism caused by the fast-forwarding of modern life. However, the truth is that these practices are primarily motivated by the principles of distinction and social reproduction of the marginal gentrifiers. Lacking sufficient economic capital to outshine wealthier groups through conspicuous consumption these initial gentrifiers deploy their dominant cultural capital to create and express a distinctive lifestyle. Because the neighbourhood transformation through gentrification has not reached a mature stage – and maybe it never will – marginal gentrifiers live side by side with old established residents and other newcomers, namely immigrants, which are benefiting from real estate opportunities in these inner city spaces where rehabilitation is still limited. According to Jorge Almeida (2011) social capital is a collective reservoir that each individual can use in certain circumstances. It is a set of outside resources, belonging to the members of a group, which an individual can claim for himself in predetermined conditions. This author distinguishes two types of capital: the inclusive and the exclusive, whose social consequences and functioning are distinct. The inclusive capital unites people of different ethnic backgrounds, age groups, geographical origins and social categories. It acts as a bridge that connects these different groups and classes. This type of capital, which is originated in heterogeneous groups, binds the different, unites the distinct, promotes social integration, and strengthens cooperation between different groups, accommodating diversity and promoting collective action. In this case, as people from different communities are brought together, the access to features not available in one of those communities is allowed. Exclusive capital, on the contrary, tends to develop in homogeneous groups, and unites those that are already equal or similar. It tends to strengthen group solidarity and reciprocity. However it may lead to antagonism against outsiders by fostering a separation between the self and the others. This type of capital is closed, centred on a group of people with a similar profile, thus tending towards the alienation of those who do not share the same characteristics or beliefs. If the latter one develops and prevails over the former at a certain neighbourhood passing through a process of residential mix, then we have an evidence of socio-spatial fragmentation. In this case, the positive outcomes associated to marginal gentrification, which involve tolerance, neighbourhood inter-group interaction and local capacity building, may never take place. The previous distinction finds a clear match in the classical definition of social capital presented by Borenholdt and Aarsother (2002). This authors bipartite explanation considers the existence of two basic dimensions, the bridging (social) capital and the bonding (social) capital, the first one corresponding to the external links of the individuals or groups and the second to the internal relations and respective sets of norms of those same social agents. The bridging capital finds a notorious correspondence in Jorge Almeidas (2011) inclusive capital and the bonding capital is largely a match for the exclusive type. Also worthy of notice for the purposes of the current paper is the work produced by Robert Putnam (2007), especially for two methodological reasons: first because one of his most important premises lies on the assumption that (ethnic) diversity tends to reduce social capital, which – although this topic is not the main focus of this text – cannot help to be a particularly interesting ancillary leitmotif when ones intention is to analyse two multi-ethnic neighbourhoods; and second because, in his explanation of the essentials of social capital, Putnam contends that this notion comprises two main types of elements, namely the cultural or cognitive aspects (such as sense of attachment, trust or social norms) and the structural or behavioural ones, which include friendships, acquaintances, family relations and other social networks, the latter being the empirical focus of the current article.IV. FRAMING THE PICTURE(S) I: THE TWO CASE-STUDY NEIGHBOURHOODS

As posited earlier, to provide an empirical reading of the connexions between (marginal) gentrification, ethnicization and inner city socio-spatial fragmentation, a comparative analysis between two multi-ethnic neighbourhoods in two Southern European cities, respectively Mouraria in Lisbon (Portugal) and San Francisco in Bilbao (Basque Country, Spain), has been trailed. The primary criterion for the selection of these two areas related to their territorial specificities, especially the fact that both of them are located near the (old) traditional centre of their respective cities. Their condition as inner-city (pre)modern and working-class neighbourhoods gave them the likelihood to, in the current period of post-modernization and frag-mentation in major cities in Western countries, gain other social functions, as receptacles of both international labour migrants and (marginal) gentrifiers, thus proving to be interesting cases for the study of contemporary dynamics of the social production of fragmented space.

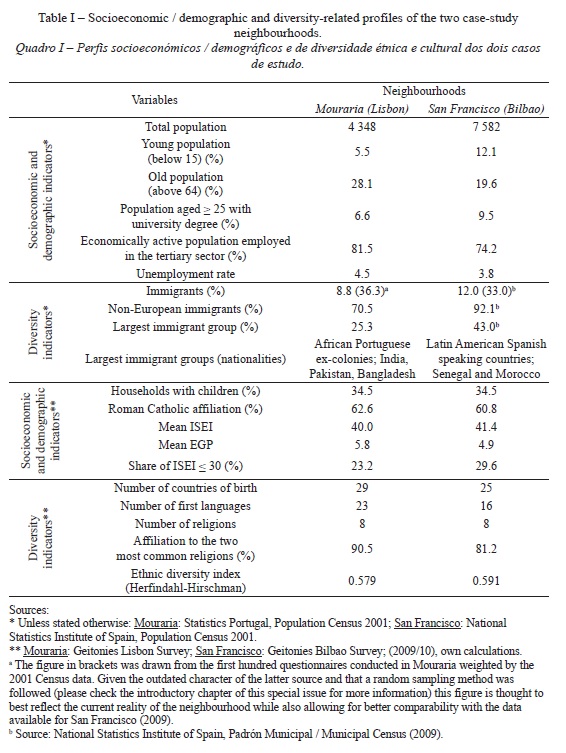

Although bearing a past intimately related to otherness as an important backdoor to the city (Malheiros, 2010), Mouraria has intensified its function as an immigrant reception area only in the last three decades of the 20th century, following the independence of the Portuguese colonies in Africa. The arrival of immigrants from these countries in the 1970s and 1980s was followed, in the 1990s, by the establishment of less-likely visitors, coming from India, Pakistan and later from China and Bangladesh (Malheiros, 2010). Data from the 2001 Census (Statistics Portugal, 2001) reveal that the area concentrated approximately 9% of individuals holding a foreign nationality, a figure clearly above that of the city of Lisbon as a whole (3,5%). Results from the GEITONIES fieldwork (held in 2009-10)ii point out that the neighbourhood may have been consolidating its role as an area of immigrant (at least temporary) settlement in the last decade, given that 86% of the immigrants interviewed had arrived there in the decade before the survey has taken place and more than half of them (53%) in the five years prior to the interview. Following the 1990s trends, Asian immigrants appear to continue to be the ones arriving with greater intensity. Despite being one of Bilbaos historical neighbourhoods, San Franciscos development occurred especially during the second half of the 19th century as an area of working-class settlement. At that time, the majority of its population was composed by mine workers and their families (Setién et al., 2010). The substantial arrival of immigrants to Bilbao in the last thirty years, and especially since the mid-1990s, has had the effect of establishing San Francisco as one of the citys reference areas for the settlement of international migrants. According to data from the 2001 Census (INE España, 2001), approximately 12% of the neighbourhoods residents held a foreign nationality. In less than a decade, this figure had risen to a striking 33% (INE España, 2009). Latin American immigrants (especially Bolivians, Ecuadorians and Colombians) are the most frequent. However, and contrarily to what is the case for the city as a whole, Sub-Saharan (especially from Senegal), Maghrebian (Moroccans and Algerians) and Chinese immigrants are also among its most numerous constituents (Setién et al., 2010). Evidence on the existence of gentrification in the two case-study neighbourhoods (and even in the cities they are located in) is fairly scarce. This is especially true for the case of Mouraria, in Lisbon. The un-arguably most thorough and in-depth works on gentrification in Lisbon (Mendes, 2008; Rodrigues, 2010) do not address directly (from an empirical point of view) the area of Mouraria. However, Rodrigues (2010) acknowledges this areas gentrifiers as being mostly from the marginal gentrifier category. This was later corroborated by Malheiros et al. (2012) who, through empirical work centred on the practices and discourses of social and ethnic mixing by some of the neighbourhoods new-comers, also found out that some of these new residents had in fact fairly high human and cultural capitals not equalled by their economic capital, thus fitting into the categories of marginal gentrifiers (Rose, 1984) and even of the so-called left-liberal (and tolerant) new middle class (Ley and Mills, 1986; Ley, 1994, 1996; Butler, 1997). Although holding on to different methodologies and focusing primarily on distinct processes, recent academic works on Mouraria appear to be unanimous in recognising its increasing social, cultural and ethnic diversity (as the outcome of processes like marginal gentrification and ethnicization), and the blending of this with an earlier traditionalism, as one of its most contemporary and distinguishable traits, one posing many trials to this polyphonic (Menezes, 2012) and curbed between traditionalism and cosmopolitanism (Mendes, 2012) neighbourhood (Malheiros et al., 2012; Menezes, 2004). On the other hand, last decades very active policies (and politics) of urban re-generation in Bilbao, which find clear expression in the construction of the Guggenheim Museum (of modern and contemporary arts) in 1997, or the regeneration of the citys urban waterfront (of the Nervión River) that followed it, are acknowledged as having acted as catalysts for the gentrification of some of Bilbaos inner-city neighbourhoods. Cameron and Coaffee (2005) argue that Bilbao is one of the finest examples of deliberate and planned (post-modern) urban regeneration associated to the symbolic and economic characters of the arts (and more broadly the culture) sector. Vicario and Martinez Monje (2005) go further on that statement by acknowledging that gentrification – and the corresponding social (and ethnic) polarization brought along with it – in the so-called area in and around Bilbao-La Vieja (including San Francisco, a neighbourhood clustered between natural and man-made physical boundaries, one of them being the regenerated waterfront of the Nervión River), might be one of the most important (although scarcely studied) faces of the so-called Guggenheim Effect. A very interesting comparative insight on the contemporary changes going on in the two neighbourhoods and in the cities around them, is provided in the documentary Identibuzziii where the hybrid social and cultural character of both areas is visually explored. The common points found between the two in the documentary are nothing short of striking. A synthesis of some of the social, economic, demographic and ethnic-related most relevant features of the two neighbourhoods is shown in table I.

Results presented in the upper half of the table were drawn from official statistics (INE España, 2001, 2009; Statistics Portugal, 2001); primary and directly comparable data from the fieldwork undertaken both in Lisbon and Bilbao were made available in the bot-tom half. The figure in brackets was drawn from the first hundred questionnaires conducted in Mouraria weighted by the 2001 Census data. Given the outdated character of the latter source and that a random sampling method was followed (please check the introductory chapter of this special issue for more information) this figure is thought to best reflect the current reality of the neighbourhood while also allowing for better comparability with the data available for San Francisco (2009). The figures presented in the table show, as already had been manifested in the documentary Identibuzz, a high degree of similarity between the two areas under study, particularly in what concerns their character(s) as multi-ethnic enclaves – expressed, for example, by similar percentages of immigrants, both in 2001 and more recently, signalling parallel evolutionary patterns; and proximate values presented by an ethnic diversity indexiv – and their residents socioeconomic (low-middle class) profilev. When compared to those of San Francisco, Mourarias residents appear to be somewhat older. Considering dimensions of immigrant diversity other than the ethnic diversity index (number of first languages spoken, number of religions, among others) Mouraria also appears to be a slightly more diverse area. The theoretical and empirical evidence presented on this section highlights that, both from a territorial and a socioeconomic point of view, the two case-study areas present similar profiles, hence being potentially comparable for the purposes of the current paper.

V. FRAMING THE PICTURE(S) II: THE FOUR GROUPS OF ANALYSIS

In the previous section some of the most important characteristics of the two case-study neighbourhoods were introduced. Various parallels between them were identified legitimizing their character as comparable contexts. A presentation of the methodological considerations that relate to the operationalization of these areas comparable character will now take place, holding in thought the papers conceptual purposes. The guiding hypothesis is that these two neighbourhoods new-comers carry along with them a renovated portfolio of (social, cultural, ethnic) values that differ from the ones shared by their traditional residents. This new behavioural framework that arrives in the neighbourhood not only influences the existing perceptions and attitudes but also the socio-spatial characters of these individuals practices and social relations, presenting evidence of increasing fragmentation.

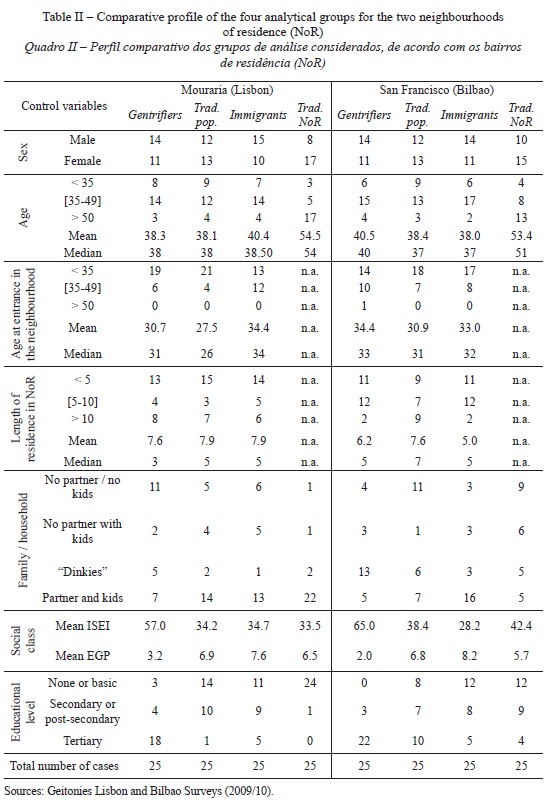

Four groups of residents have been selected from the two neighbourhoods experimental samples each comprising the same number of individuals, thus allowing for comparability between them. The first group selected comprised respondents with a profile in line with that acknowledged as typical of a gentrifier. Age (current and at time of arrival at the area) (20-49 years) and level of education (post-basic education), were combined with data concerning job trajectories (e.g. history of main occupations), family pro-file (at the time of arrival at the neighbourhood and at the time of inquiry), reasons pointed out to move into the area and qualitative information gathered during the survey (e.g., a self-proclaimed cosmopolitanism). A second group – labelled traditional population (trad. pop.) – was then created. Their profile was set to be similar to that of gentrifiers in what concerned variables gender, age, age at time of arrival at the neighbourhood, and length of residence in the neighbourhood. The purpose was to isolate (as independent variables) the educational level and the socioeconomic profile of these groups (lower in the case of the gentrifiers) as possible conditioning factors for their (social and spatial) dynamics of interaction and networking. A third group composed of international immigrants was also created, holding similar characteristics in terms of the same four variables mentioned above. The purpose here was to detach these individuals ethnic capital as a conditioning factor. Finally, a fourth group was established, composed solely of individuals that, notwithstanding their social and demographic characteristics, had always lived in their current neighbourhood of residence (called traditional residents from the neighbourhood – trad. NoR), trying to trace whether this entitlement would manifest itself in terms of the social and spatial configurations of these residents social networks. Respondents who owned or were employed in retail or other direct commercial services, and immigrants with low proficiency in the language of the country of residence were not considered because – given their influence upon the opportunities for developing direct interactions – these two characteristics could have had a deviant effect on the final results. Table II presents the comparative profile of the four analytical groups for the two neighbourhoods.

An intra-neighbourhood analysis confirms the impacts of the instrumental considerations that guided the selection of the operational groups. An inter-neighbourhood analysis presents some other aspects worthy of notice. A first one is the higher socioeconomic level of the (three) native groups found in San Fran-cisco, especially relevant for the trad. NoR and the gentrifiers. The opposite is the case when we consider the immigrants: If, in Mouraria, their socioeconomic class and occupation levels appear to be fairly in line with those of the two traditional groups, in San Francisco evidence of higher social and, particularly, ethnic polarization is found, with immigrants assuming a markedly lower occupational standard than natives. Traditional residents in San Francisco are also more educated than the ones found in Mouraria. Finally, referring specifically to the gentrifiers, those living in San Francisco seem to be wealthier and probably a little less marginal. The presence of artists and single and childless gentrifiers is more important in Mouraria, while in San Francisco households with double income and no kids (the so-called dinks) and respondents employed in social work, health and education-related activities are the categories that achieve higher frequencies. The establishment of the previous analytical groups allowed isolating empirically some of the aspects – the ethnic capital, the socioeconomic profile, the level of education, and the degree of neighbourhood attachment – that are hypothesized to act as conditions for the social and spatial dynamics that guide the establishment of social networks in post-modern and fragmented contemporary urban spaces. The following section will lay its attention on the social and spatial characteristics of these individuals social networks, analysed under the scope of the (post-modern and) fragmented city thesis (Barata Salgueiro, 1997, 1998, 1999).

VI. THERE GOES THE NEIGHBOURHOOD?: GENTRIFICATION, ETNICIZATION AND SOCIAL NETWORKS

As mentioned earlier, the main purpose of this cross-comparative paper is to explore, for two inner-city Iberian contexts, if and how the alteration of practices, social relations and spatial embeddedness that appear as outcomes of gentrification and residential ethnicization may be posited as an evidence of fragmentation. It is intended to do so through the analysis of the social networks of the individuals that compose the four analytical groups, drawn from the samples of respondents surveyed in the two inner-city neighbourhoods. Two different levels of intimacy of social relations were considered: i) what was called the current global social network, where respondents were asked to think about the people with whom they spent free time, they shared advices and confidentialities or to whom they asked (or were asked) for help; and ii) the most important contacts, where the individuals surveyed could name up to eight persons who they considered to be their most relevant acquaintances. In both cases, people living in the respondents households were not eligible. Before advancing to the spatial configurations of their social networks – and hence to acknowledging the relevance of neighbouring relations and the neighbourhood as a site for their most intimate social contacts – attention will be laid upon the characterization of these respondents social networks, referring to aspects such as their dimension and social / ethnic composition.

1. Dimension and composition of social networksRegarding the first of the two aspects – the dimension of the social networks – a primary result is that inter-neighbourhood differences are consistently more visible than those found between different groups in the same study-area, for the two levels of intimacy or importance considered. For example, residents in Mouraria claimed to have larger global social networks, with an average of 3.5 and a median of 2 contacts, against respectively 1.4 and 1.3 mentioned by respondents in San Francisco.

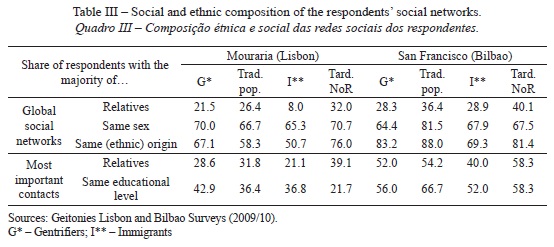

An analysis of the social composition of these networks shows more complex results. Table III presents the share of respondents whose majority of social contacts belongs to a certain social profile, for both the global social networks and the most important contacts.

If, for some of the features considered, inter-neighbourhood differences are still the most prominent – e.g. the higher percentage of relatives in the global social networks of immigrants in San Francisco, when compared with the same figure for Mouraria, a situation that points to lower levels of family and kin endogamy in the latter case – some interesting (and fairly consistent among the two areas) divergences between analytical groups appear to emerge. Relatives are generally viewed as more relevant social contacts for the two traditional groups than for immigrants and gentrifiers. If in the former case this may have to do with the fact that, being foreigners, they are less able to be involved in day-to-day interactions with nearby relatives, explanation for the latter may come from the words of authors like Butler (1997) and Ley (1994, 1996) who frame gentrifiers as being part of a left-liberal new middle class characterized by a higher disregard for traditional values such as religion or family. Nonetheless, a fine-grained analysis shows that for all groups the importance of relatives gets higher as the level of intimacy of relationships increases. If respondents do not appear to spend much of their free time with their relatives, conversely they tend to recur to them more often for advice and assistance. And they also grant them more regularly a position as one of their most important contacts. Also, family members seem to be more valued by all groups in San Francisco than they do in Mouraria. The distance between the two neighbourhoods expressed by this pattern is also made more relevant as the level of intimacy increases. The majority of the respondents social networks – no matter what their analytical group or neighbourhood of residence – are composed of people of their own gender. Contrariwise to the tendency identified for the interactions with relatives, this figure gets transversally lower when the level of intimacy increases. Probably this has to do with the fact that both female and male direct relatives (i.e. parents, grandparents or even grown-up progenies) are targeted when respondents look for advice and/or assistance. Evidence about the educational level of the respondents and that of their most important contacts may allow to understand if their networks point out to any relevant trends of social mix, not only at the neighbourhood level but also at the general (society) level. This could be particularly interesting for the case of gentrifiers at the light of recent (and critical) works on the (supposed) emancipatory character of gentrification (Lees, 2000, 2008; Davidson, 2010). Analysis of the previous variable indicates that in San Francisco most respondents interact with individuals holding the same educational level as they do. This is clearly not the case for Mouraria where all groups have stated that the majority of their most important contacts hold an educational level other than their own. Again, it must be noticed that these results should be viewed as a mere and general proxy for social mix tendencies. Attempting to further enhance the analysis of the previous indicator a comparative inquiry of the ethnic background of the respondents and that of their social contacts presents some interesting results. If earlier ideas about mixing in Mouraria are not fully confirmed when we look at ethnic mix patterns, results for this neighbourhood end up being strikingly more positive than those found for San Fran-cisco where – with the exception of immigrants – up to 80-90% of the respondents claimed that the majority of their contacts were from their own ethnic origin (table III). This difference is also noticeable when we examine the number of inter-ethnic (i.e. from a different origin) most important contacts mentioned in the two neighbourhoods: In Mouraria, around 40% of the respondents belonging to the first three analytical groups – i.e. excluding that with people who have always lived in their current neighbourhood of residence, who were clearly less prone to establish inter-ethnic contacts, at only 9% – claimed to have at least one inter-ethnic acquaintance among their most important contacts. Contrarily, in San Francisco only the immigrants rose to such high figures with gentrifiers and the two traditional groups presenting fairly low results at around 10-15%. 2. Social networks and spatial embeddedness Previous evidence was centred on the social characteristics of the four groups social networks, for the two inner-city case-study neighbourhoods. An examination of the spatial configuration of those networks – highlighting the potential role of the neighbourhood for the establishment of contacts and as a meeting place – will now be undertaken. Results of these spatial dynamics are portrayed in table IV.

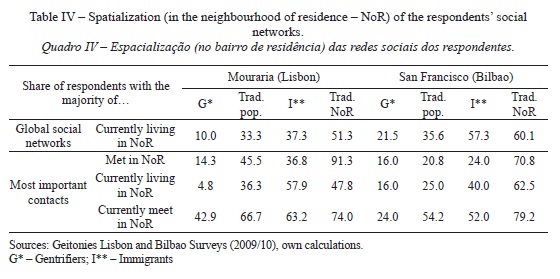

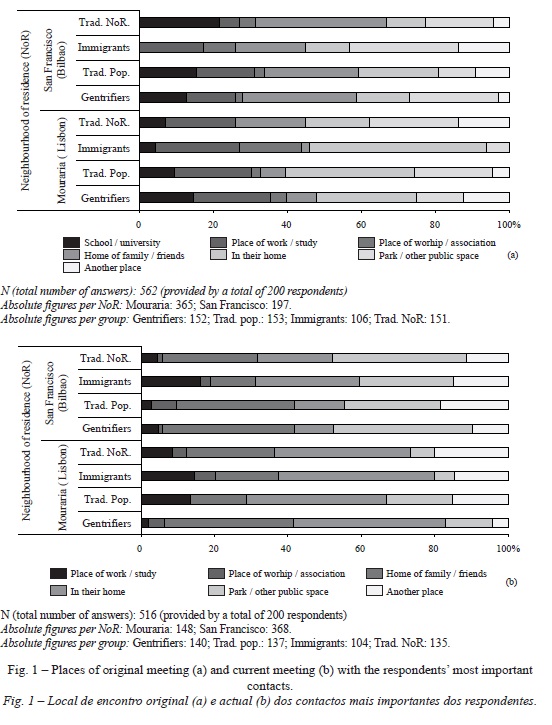

As expected, when asked about the place where they originally met their most important contacts, for the two case-study inner-city areas the traditional neigh-bourhood residents (trad. NoR) presented higher frequencies than those expressed for the other three groups, reaching figures as high as 90% and 70%, respectively for Mouraria and San Francisco. Although holding on to extremely lower numbers (always below 50%), results for the other three groups in Mouraria – except maybe for the gentrifiers, where similar numbers among the two neighbourhoods were found – were always more positive than those of San Francisco, hence confirming the aforementioned trends. However, a mixed picture is painted when one goes on to analyse the place where the respondents social contacts are currently living. As far as their global social networks are concerned, San Franciscos importance as a place of residence for the respondents contacts generally displays higher records than those found for Mouraria. This is true for the four groups of respondents considered. In both neighbourhoods, gentrifiers are the ones whose contacts reside the least frequently in their neighbourhood of residence. Both immigrants in Mouraria and traditional neighbourhood residents in San Francisco concentrate the majority of their most important contacts in their current neighbourhood. In a similar vein, and for both Mouraria and San Francisco, the majority of the traditional neighbourhood residents global social networks also reside in their current area of residence. Deeper clarification on the spatial dynamics of these residents social networks appears to arise when the answers to the question where do you meet your most important contacts nowadays? are examined. The neighbourhood ascends as the most important meeting place for all groups other than the gentrifiers in both Mouraria and, although to a lesser extent, San Francisco. The traditional neighbourhood residents are again – as was the case for the variable analysing the place where they first met their most important contacts – the ones that use their area of residence more frequently. Further insight on the spatialization of these intimate social contacts – and also, though indirectly, on the importance of the neighbourhood as a meeting place – is provided by figure 1, where a discrimination of the actual places where both the first and the current contacts were/are established is provided.

Concerning the places where they originally met their most important contacts (i.e. the place where their first meeting occurred) fairly similar patterns may be found amongst the two neighbourhoods. Private spaces such as the respondents home or the home of family, friends or acquaintances appear to divide their prominence as places of original meeting with public or semi-public spaces such as schools / universities (particularly relevant for gentrifiers in Mouraria and traditional neighbourhood residents in San Francisco), places of worship / associations (more important for immigrants, especially for those living in Mouraria) and parks or other public spaces. The respondents places of work and their homes present higher general incidence rates for Mouraria which, especially for the latter, may help explain the aforementioned tendency for this neighbourhoods respondents to show higher frequencies of contacts in the neighbourhood than was the case for San Francisco. Some curious results are also found by looking at the places where respondents meet their most important contacts nowadays. For instance, in Mouraria, the respondents homes and those of their family and friends amount to a total of 60% for immigrants and the traditional neighbourhood residents and of 75% for the gentrifiers as a place of encounter between these respondents and their most important contacts. This may, again, act as an explanation for the higher relevance of Mouraria as a meeting place, when compared to San Francisco, as identified above. Contrariwise to Mourarias residents, to whom private spaces are the most relevant, to (partially rehabilitated) San Franciscos inhabitants, parks and other public spaces gain relative prominence – accounting for about 25% for immigrants and traditional new-comers and around 37% for gentrifiers and the neighbourhoods traditional residents – as meeting places. This may be an evidence of the higher intensity of street life in Spanish cities, including the Basque country ones, that affects all population groups, but may also result from the higher intensity of the rehabilitation process experienced by Bilbao, which generally improved the quality of public spaces, including those in areas nearby San Francisco (Vicario and Martinez Monje, 2005; IDEA/UPM, 2010: 22-29). Places of worship and working sites generally lose relevance as places of current meeting when compared to their meaning as places of first meeting. Following a classical path in social relations, when these get deeper the places where such contacts occur tend to be more internalised (e.g. take place at home). Nevertheless, in the case of Bilbao an increasing use of public spaces may also be found, a process that seems to confirm an adjustment to a more intense street life.

VII. FINAL REMARKS

The empirical elements collected in San Francisco and Mouraria shed light on some dimensions of the fragmented socio-spatial processes taking place in both neighbourhoods, in a context marked by simultaneous marginal gentrification and ethnicization associated to the settlement of non-EU labour migrants.

Considering first the social spectrum and the inherent social networks established in both neighbourhoods, not only are immigrants more polarized in terms of their social class and job opportunities in San Francisco than in Mouraria but also this appears to be expressed in less ethnically diverse networks and fewer inter-ethnic intimate contacts for all groups, especially for the non-immigrants, in the Basque neighbourhood. Additionally, and specifically for the gentrifiers, ideas of increased (ethnic) mix possibilities due to their tolerant and liberal character are not expressed directly in terms of their social networks and interactions as already advocated in the works of authors such as Rose (2004), Lees (2008), Davidson (2010), or, for the case of Mouraria, Malheiros et al. (2012). Even so, and whether this is a cultural capital / social class effect or a neighbourhood / country effect, one should not disregard that Mourarias less wealthy, and thus more marginal, gentrifiers end up establishing more relationships with individuals holding a different educational level and, more prominently, with those with a different ethnic background than do their counterparts in San Francisco. Somehow, this contributes to feed the hypothesis about the specificity of marginal gentrification advocated by authors like Van Criekingen and Decroly (2003) and it also reveals some possible benefits of a primary state of gentrification as is the case in Mouraria. Concerning the elements on the spatial embeddedness of the respondents networks, it is possible to say that as expected traditional neighbourhood inhabitants are the ones making a greater use of their area of residence as a place for social encounters. Of the three groups of new-comers, the gentrifiers show up as the least confined to their area of residence, a trend made even clearer when considering only its public spaces. These correspond to the group that develops spatialities possessing a more diffused and fragmented consistency and the one whose social and cultural practices are more scattered across different, separate and distant places. For many, the spatiality of a particular socio-cultural practice is no longer defined by territorial continuity but rather by going to a series of places, often standardised, whose sense derives from the complementary practices each one involves. Relatively distinct outcomes were identified for the cases of immigrants and traditional new-comers. For both groups, the neighbourhood emerges as an important spatial repository for the establishment of close relationships, not only in terms of their global social networks but also concerning their most important contacts. Alongside the more obvious traditional neighbourhood residents these appear to be the groups that effectively live (in) the neighbourhood and use their (public) spaces more often to socialise. Finally, although interactions with co-residents tend to be more common in San Francisco, Mouraria is more often used by residents as a place for social encounters, which tend to take place indoors, in the homes of respondents and in that of their family and friends. In the case of San Francisco, the private spatiality of contacts is less evident and public space assumes a more prominent role as a promoter of interactions and contacts, though these do not occur exclusively inside the neighbourhood. The higher role of public space as a catalyst for social interactions in the case of San Francisco is an example of a contextual socio-spatial element, once it reproduces the overall trend that discloses the higher intensity of outdoor city life in Spanish cities when compared to Portuguese ones. Furthermore, and even aware of that contextuality, one cannot help noting that the neighbourhood with the higher levels of interaction in the public space (i.e. San Francisco) is also that with apparently lower levels of ethnic mixing. Understanding more clearly whether this is a cultural or social specificity or a neighbourhood / country effect would prove to be extremely relevant, not only for the strictu sensu academic debate on the democratic access to urban public spaces but also for the implementation and evaluation of urban policies in general, especially those that address issues of citizenship and the right to the city. Such an understanding would involve further studies at the neighbourhood scale like the one undertaken here, applied to other contexts, complemented with others based on the use of different methodologies (e.g. urban ethnography), including those more centred on observing, describing and critically analysing the geographies and ethnographies of the micro-scale processes characteristic of the contemporary social appropriation of urban spaces. Despite the different contextual elements that characterise San Francisco (Bilbao) and Mouraria (Lisbon) – younger population with higher levels of socio-ethnic polarisation in the former case; more evidence of the marginal type of gentrification in the latter one; higher use of public space in the Basque case – the processes of gentrification and ethnicization are prompting more complex and fragmented models of social relations as well as different forms of socio-spatial embedding in both places. As we have seen, these vary according to the four experimental groups of residents (marginal gentrifiers, traditional new-coming residents, immigrants and established / traditional residents from the neighbourhood) who, especially in San Francisco, display limited levels of social interaction outside their own specific socio-ethnic systems. Using the terminology of Almeida (2011), exclusive social capital, which somehow corresponds to the idea of bonding social capital (Baernholdt and Aarsother, 2002), seems to impose itself upon inclusive social capital (the bridging type), limiting the processes of local community building – identified by the supporters of residential mix – and potentially fostering social and ethnic antagonisms. In order to mitigate these unwanted outcomes, participative rehabilitation processes – eventually comprehending self-rehabilitation – with public support targeting established tenants and newcomers (immigrants, marginal gentrifiers) and initiatives promoting local capacity building and cross-culturality could be examples of good practices. In the line of Borja (2005: 49) it is crucial to develop systems of neighbourhood democratic management and the will to produce city as public space. Finally, perceiving the historical neighbourhood-space as a key element of building the newcomers, immigrants or gentrifiers identities, does not conform to applied classical theory. This goes against the very essence of identity, which in itself is affirmed and defined in the difference – and not exclusively in homogenous social and cultural practices – induced and conditioned by the local environment of a social class. This perspective gives an account of the changes implicit in the geography of the social appropriation of urban space in late-modern society and economy and, at the same time, it reveals the shortcomings of the traditional theoretical models that have been adopted with the aim of explaining phenomena such as filtering down processes and modern and industrial city socio-spatial segregation.BIBLIOGRAPHY

[ Links ]

Arbaci S, Rae I (2012) Mixed tenure neighbourhoods in London: policy myth or effective device to alleviate deprivation. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(2): 451-479. [ Links ]

Baernholdt J, Aarsother N (2002) Coping strategies, social capital and space. European Urban and Regional Studies, 9(2): 151-165. [ Links ]

Barata Salgueiro T (2006) Oportunidades e transformação na cidade centro. Finisterra – Revista Portuguesa de Geografia, XLI(81): 9-32. [ Links ]

Barata Salgueiro T (1999) Ainda em torno da fragmentação do espaço urbano. Inforgeo, 14: 65-76. [ Links ]

Barata Salgueiro T (1998) Cidade pós-moderna: espaço fragmentado. Inforgeo, 12/13: 225-235. [ Links ]

Barata Salgueiro T (1997) Lisboa: metrópole policêntrica e fragmentada. Finisterra – Revista Portuguesa de Geografia, XXXII (63): 179-190. [ Links ]

Borja J (2005) La ciudad conquistada. Alianza Editorial, Madrid. [ Links ]

Bourdin A (1984) Le patrimoine réinventé. PUF, Paris. [ Links ]

Bourdin A (1980) Réhabilitation des vieux quartiers et nouveaux modes de vie. Recherches Sociologiques, 11(3): 259-275. [ Links ]

Bourdin A (1979) Restauration rehabilitation: lordre symbolique de lespace neobourgeois. Espaces et Sociétés, 30/31: 15-35. [ Links ]

Bridge G (2001) Bourdieu, rational action and the time-space strategy of gentrification. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 26: 205-216. [ Links ]

Bridge G, Butler T, Lees L (2012) Mixed communities: gentrification by stealth? Polity Press, London. [ Links ]

Butler T (1997) Gentrification and the middle classes. Ashgate, Aldershot. [ Links ]

Butler T, Robson G (2001a) Coming to terms with London: middle-class communities in a global city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 25(1): 70-85. [ Links ]

Butler T, Robson G (2001b) Social capital, gentrification and neighbourhood change in London: a comparison of three south London neighbourhoods. Urban Studies, 38(12): 2145-2162. [ Links ]

Cameron S, Coaffee J (2005) Art, gentrification and regeneration: From artist as pioneer to public arts. European Journal of Housing Policy, 5(1): 39-58. [ Links ]

Carmo, R M (2006) Contributos para uma sociologia do espaço-tempo. Celta Editora, Oeiras. [ Links ]

Caulfield J (1994) City form and everyday life. Torontos gentrification and critical social practice. University of Toronto Press, Toronto. [ Links ]

Clay P (1979) Neighbourhood renewal: middle-class resettlement and incumbent upgrading in american neighbourhoods. D.C. Health, Lexington, Massachusetts. [ Links ]

Davidson M (2010) Love thy neighbour? Social mixing in Londons gentrification frontiers. Environment and Planning A, 42(3): 524-544. [ Links ]

Dematteis G (2001) Shifting cities. In Minca, C (ed.) Postmodern geography. Theory and praxis. Blackwell, Oxford. [ Links ]

Engels F (1844 [1971]) A questão do alojamento. Cadernos para o diálogo, nº3, Porto. [ Links ]

Fonseca M, McGarrigle J (coord.), Esteves A, Sampaio D, Carvalho R, Malheiros J, Moreno L (2012) Modes of interethnic coexistence in three neighbourhoods in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area: a comparative perspective. Edições Colibri, Lisbon. [ Links ]

Ganzeboom H, Treiman D (1996) Internationally comparable measures of occupational status for the 1988. International standard classification of occupations. Social Science Re-search, 25: 201-239. [ Links ]

Graham S, Marvin S (2001) Splintering urbanism. Networked infrastructures, technological mobilities and the urban condition. Routledge, London. [ Links ]

IDEA/UPM (2010) Experiencias españolas en movilidad sostenible y espacio urbano. Instituto para la Diversificación y Ahorro de la Energía y Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid. [ Links ]

INE España (2001) Population and housing census 2001. Madrid. [ Links ]

INE España (2009) Padrón municipal 2009. Madrid. [ Links ]

Lees L (2008) Gentrification and social mixing: towards an inclusive urban renaissance? Urban Studies, 45(12): 2449-2470. [ Links ]

Lees L (2000) A reappraisal of gentrification: towards a geography of gentrification. Progress in Human Geography, 24(3): 389-408. [ Links ]

Ley D (1996) The new middle class and the remaking of the central city. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Ley D (1994) Gentrification and the politics of the new middle class. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 12(1): 53-74. [ Links ]

Ley D, Mills C (1986) Gentrification and reform politics in Montréal 1982. Cahiers de Géographie du Québec, 30 (81): 419-427. [ Links ]

Malheiros J (2012) Framing the Iberian model of labour migration: employment exploitation, de facto deregulation and formal compensation. In Okolski M (ed.) European immigrations: trends, structures and policy implications. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam: 159-178. [ Links ]

Malheiros J (2010) Comunidades indias en Lisboa: Creatividad aplicada a las estrategias empresariales y sociales? Revista CIDOB dAfers Internacionals, 92: 119-138. [ Links ]

Malheiros J, Carvalho R, Mendes L (2012) Etnicização residencial e nobilitação urbana marginal: processo de ajustamento ou prática emancipatória num bairro do centro histórico de Lisboa? Sociologia – Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, special issue: Imigração, Diversidade e Convivência Cultural: 97-128. [ Links ]

Martinez Veiga U (1999) Pobreza, segregación y exclusión espacial. Icaria, Barcelona. [ Links ]

Mendes M (2012) Bairro da Mouraria, território de diversidade: entre a tradição e o cosmopolitismo. Sociologia – Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, special issue: Imigração, Diversidade e Convivência Cultural: 15-41. [ Links ]

Mendes L (2011) Postmodern city, gentrification and the social production of fragmented space. Cidades, Comunidades e Territórios, 23: 82-96. [ Links ]

Mendes L (2008) A nobilitação urbana no Bairro Alto: análise de um processo de recomposição socio-espacial. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade de Lisboa, [ Links ]

Menezes M (2012) Debatendo mitos, representações e convicções acerca da invenção de um bairro lisboeta. Sociologia – Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, special issue: Imigração, Diversidade e Convivência Cultural: 69-95. [ Links ]

Menezes M (2004) Mouraria, retalhos de um imaginário. Significados urbanos de um bairro de Lisboa. Celta Editora, Oeiras. [ Links ]

Musterd S, Andersson R (2005) Housing mix, social mix and social opportunities. Urban Affairs Review, 40: 761-790. [ Links ]

Navez-Bouchanine F (2002) La fragmentation: sources et définitions. In Navez-Bouchanine F (ed.) La fragmentation en question: des villes entre fragmentation spatiale et fragmentation sociale? LHarmattan, Paris. [ Links ]

Putnam R (2007) E Pluribus Unum: diversity and community in the twenty-first century – The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies, 30 (2): 137-174. [ Links ]

Rhoades S (1993) The Herfindahl-Hirschman index. Federal Reserve Bulletin, issue Mar: 188-189. [ Links ]

Rodrigues W (2010) Cidade em transição. Nobilitação urbana, estilos de vida e reurbanização em Lisboa. Celta Editora, Oeiras. [ Links ]

Rose D (2004) Discourses and experiences of social mix in gentrifying neighbourhoods: a Mon-treal case study. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 13(2): 278-316. [ Links ]

Rose D (1984) Rethinking gentrification: beyond the uneven development of Marxist urban theory. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 2(1): 47-74. [ Links ]

Setién M, Bartolomé E, Ibarrola A, Maiztegui C, Vieytez E, Santibáñez R, Vicente T (2010) Geitonies – City Survey Report: Bilbao. Universidad de Deusto, Bilbao [unpublished report]. [ Links ]

Statistics Portugal (2001) XIV Recenseamento Geral da População; IV Recenseamento Geral da Habitação. Lisbon. [ Links ]

Smith N (1996) The new urban frontier. Gentrification and the revanchist city. Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Van Criekingen M, Decroly J (2003) Revisiting the diversity of gentrification: neighbourhood renewal processes in Brussels and Montreal. Urban Studies, 40(12): 2451-2468. [ Links ]

Vicario L, Martinez Monje M (2005) Another Guggenheim effect: central city projects and gentrification in Bilbao. In Atkinson R, Bridge G (eds.) Gentrification in a global context: the new urban colonialism. Routledge, London: 151-167. [ Links ]

Zukin S (1987) Gentrification: culture and capital in the urban core. Annual Review of Sociology, 13: 129-14 [ Links ]

Received: October 2012. Accepted: March 2013

FUNDING This research has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2011) under grant agreement nº 216184 (GEITONIES PROJECT).

NOTES

i Frequently, the objectives of small landlords that rent a few inner city flats and are not inter-ested in making large investments contrast with the goals of large scale speculators involved in extensive and expensive rehabilitation operations (Martinez Veiga, 1999).

ii In the absence of official data from the 2011 Census on this topic the fieldworks results are used as a proxy. The legitimacy of these results derives from the random sampling methodology followed. For further insight on this methodology please check this issues introductory chapter or Fonseca et al. (2012).

iii Available on-line at the following weblink: http://vimeo.com/37128701

iv The ethnic diversity index used followed the algorithm of the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index. See, for example, Rhoades (1993) for further insight on how this index is computed and on how its results should be analyzed.

v For a thorough explanation about the International Socioeconomic Index (ISEI) and the Erickson-Goldthorpe-Portocarero (EGP) Class Scheme used here please check for example Ganzeboom and Treiman (1996).