Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

Print version ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.96 Lisboa June 2013

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Social networks and civic and political participation in six European cities. A quantitative study

Redes sociais e participação política em seis cidades europeias. Um Estudo quantitativo

Laura van Duin1; Erik Snel2

1PhD candidate, Academic Workplace at De Nieuwe Kans, Rotterdam (The Netherlands). E-mail: lauravanduin@gmail.com

2Assistant professor at the Department of Sociology of the Erasmus University Rottterdam (The Netherlands). E-mail: snel@fsw.eur.nl

ABSTRACT

This study examines the relation between the size and composition of social networks of people and the degree of civic and political participation using survey data of the GEITONIES-project in six European cities (Lisbon, Bilbao, Thessaloniki, Vienna, Warsaw and Rotterdam). In like with Robert Putnam's findings, we expected respondents with larger social networks to participate more. We also expected that respondents with bridging social networks (in particular with more interethnic social contacts) to participate more. We found that network size is indeed related to participation in voluntary work, but not to political participation (voting). Interethnic contacts do not contribute to civic or political participation. On the contrary, people with more intra-ethnic contacts participate more in voluntary work.

Keywords: Civic participation, political participation and social networks.

RESUMO

Redes sociais e participação política em seis cidades europeias. Um Estudo quantitativo. Este artigo analisa a relação entre a dimensão e a composição das redes sociais individuais e a participação cívica e política, utilizando dados de um inquérito efectuado no âmbito do projecto GEITONIES, em seis cidades europeias (Lisboa, Bilbau, Salónica, Viena, Varsóvia e Roterdão). Em conformidade com resultados dos estudos de Robert Putnam, seria de esperar que os respondentes com redes sociais mais amplas, tivessem maior participação cívica e política. Também se esperava que os respondentes com laços sociais fortes com indivíduos de outros grupos (em particular contactos interétnicos) tivessem maior participação. Concluiu-se que a dimensão da rede social está de facto relacionada com o exercício de actividades voluntárias, mas não com a participação eleitoral. Os contactos interétnicos não correspondem a uma maior participação cívica ou política. Pelo contrário, indivíduos com mais contactos com co-étnicos participam mais em trabalho voluntário.

Palavras-chave:Participação cívica, participação política, redes sociais.

RÉSUMÉ

Réseaux sociaux et participation politique dans six villes Européennes. Étude quantitative. Cet article analyse la relation qui pourrait exister entre la dimension de réseaux sociaux privés (associations) et la participation de leurs membres dans la vie civile et politique. Les données analysées proviennent dune enquête menée dans le cadre du projet GEITONIES, dans six villes européennes (Lisbonne, Bilbao, Salonique, Rotterdam, Varsovie, Vienne). Daprès les études de Robert Putnam, on sattendait à ce que les membres de larges réseaux sociaux participent plus que dautres. On sattendait aussi à ce que les membres de groupes ayant des liens étroits avec dautres groupes (en particulier inter-ethniques) aient une forte activité civique et politique. On a constaté que, si la dimension du réseau social entraîne une bonne relation de collaboration à des activités de volontariat, elle nimplique pas une forte participation électorale. Les contacts inter-ethniques ne contribuent pas à une plus grande participation civique ou politique. Cependant, les individus ayant des contacts intra-ethniques coopèrent plus activement aux tâches de volontariat.

Mots-clés: Participation civique, participation politique, réseaux sociaux.

I. INTRODUCTION

This study focuses on the relation between the size and composition of social networks of people and the degree of civic and political participation. Our study is based on the GEITONIES research, an international comparative study in six European cities about how interethnic interactions in local neighbourhoods may influence the creation of a more tolerant, cohesive and integrated society. In this study we focus on particular civic and political participation. Participation in civil society is often seen as crucial for a cohesive society: Individuals participate in many other networks and institutions that help to knit society together. Despite a lessened propensity on the part of many to commit themselves to group activity, political parties, trade unions and religious bodies continue to engage many people in broad social networks (Council of Europe, 2004: 14). The Council adds that governments should create favourable environments for encouraging the active participation of citizens in such bodies and activities.

In this study, we concentrate on the interrelationship between informal and more formal participation of individuals. Our main research question is whether there is a relationship between the size and composition of informal social networks and the degree of civic and political participation – measured by the participation of respondents either in several kinds of voluntary work or participation in local or national elections. Based on the work of Robert Putnam (1993; 2000) we expect a positive relationship between the two. The more people participate in informal social networks, the more they are also active in civic and political participation. We also examine whether or not what Putnam calls bridging social networks – for instance, interethnic social contacts – contribute to the extent of civic and political participation of respondents.

To answer our central question, we examine five related questions to determine the affect and degree of social participation of a person based on the qualities of their social network: 1) What relationship does the size of the individual's social network have on participation? 2) Does the educational level of the individual affect the size of his social network? 3) Does the geographical relationship between members affect participation? 4) Does the quality of relationship the individual has with other members of the social network affect participation? 5) Does the racial make-up of the social network, i.e. intra-ethnic, affect participation? These questions led to six hypotheses which will be answered in this study:

– People with a larger social network tend to participate more than people with a smaller social network (H.1).

– High-educated people have larger social networks and participate more than lower educated people (H.2).

– People with bridging social networks participate more (H.3).

This general hypothesis about how the composition of social networks is related to civic and political participation and consists of three more specific assumptions that will be examined in our analyses:

– People with more neighbourhood based social networks participate less than people whose social networks mainly consist of people living elsewhere (H.3a).

– People with more family-based social networks participate less than people whose social networks mainly consist of friends and acquaintances (H.3b).

– People, but more specific ethnic minorities, with more intra-ethnic contacts participate less than people with more interethnic contacts (H.3c).

II. INFORMAL SOCIAL NETWORKS, CIVIC PARTICIPATION, POLITICAL PARTICIPATION: ASSUMPTIONS

The idea that informal social contacts and social networks on the one hand and civic and political participation on the other are interrelated, of course, follows the work of Robert Putnam. In his early work Making Democracy Work (1993), Putnam explains the success of governments in different regions in Italy in terms of the presence or absence of a civic community. In regions with active civic communities, governments are more efficient than in places where this civic community was less, or not at all, prevalent. For Putnam, communities have a civic culture when citizens actively participate in public affairs, not only for their own behalf, but on behalf of the common good. In a civic community, citizens have equal rights and equal obligations. In this situation, a sense of commonality and norms of reciprocity develop. As a result, citizens can disagree with each other, but these disagreements can be resolved without conflicts because people are helpful, respectful and they trust each other. These virtues are fostered in the social networks citizens are engaged in.

Putnam here uses the term social capital which he defines as ...the features of social organization, such as trust, norms, and networks that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated actions (Putnam 1993: 167). Note that Putnam has a different understanding of social capital than authors like Bourdieu (1986) or Portes (1998) who emphazise the instrumental use of social capital: mobilizing resources from informal social networks. Putnam (1995) rather emphasizes the collective value of social networks that facilitate cooperation for mutual benefit. In his influential book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (2000), Putnam examines political, civic and religious participation in relation to social networks. He mentions five reasons why social networks are important for society: 1) it is easier to solve collective problems, as unsafe neighbourhoods, 2) it creates awareness for common interest, 3) more mutual trust makes it easier for businesses to conduct negotiations and transactions, 4) hereby the speed of information streams increases and 5) social relations promote happiness and health. However, Putnam argues that social capital and social participation are declining in modern societies like the USA, as a result of television and urban sprawl among other things.

Another element in Putnams theory of social capital is the distinction between bonding and bridging social capital. Bonding social capital refers to social networks within certain groups and communities; social relations that are ...inward looking and tend to reinforce exclusive identities and homogenous groups. Bridging social capital, on the other hand, is outward looking and refers to social relations that trans-cend fixed groups and group identities. Putnam particularly emphasizes the collective value of bridging social capital: Bridging social capital can generate broader identities and reciprocities whereas bonding social capital bolsters our narrower selves (Putnam 2000: 22, 23). While bridging networks are helpful for obtaining information and support from outside, bonding networks are about solidarity and cohesion within groups with a shared identity. Both types do not exclude each other but exist continuous in a certain degree next to each other.

Our analyses focus on Putnams assertion that the size and composition of informal social networks are related to civic and political participation. In his view, informal social contacts and participation in social networks result in generalized reciprocity and collective feelings of trust. These traits, in turn, result in a greater inclination to contribute to public goods. These considerations result in the general hypothesis of our analysis: the more informal contacts and the larger social networks, particularly social networks that bridge existing borders between social categories, the more civic and political participation.

Putnam was not the first to pay attention to the relationship between social networks and civic and political participation. There is in fact a rich literature about this topic. In an extensive overview, Wilson (2000: 219, 220) points out evidence for the role of both individual factors and social resources in explaining voluntary activities. With regard to individual factors, educational level is a consistent predictor of volunteering. Higher educated individuals are more aware of problems, are more emphatic and self-confident, and are more likely to be asked to volunteer. On the other hand, extensive social networks and multiple organizational memberships in-crease the chances of volunteering. These social resources also explain why people of higher socioeconomic status volunteer more: they join more organizations and are more likely to be active in them (Wilson and Musick, 1997). Extensive social networks and organizational activity increase the chances to be asked to volunteer and the incentive to participate (we do not want to let our friends down). Moreover, social ties and organizational activity generate trust which is a general drive for participation in voluntary work.

Also the relationship between social networks and organizational activity and political participation is widely researched. Political participation, on the one hand, is also related to individual factors, in particular educational level. Higher educational level increases the knowledge, skills and resources that support political participation (Verba, Schlozman and Brady, 1995; La Due Lake and Huckfeldt 1998). On the other hand, Lim (2008) points out a range of studies that confirm the relation of social networks and political participation, where social networks function as a recruitment channel in voting, campaigning and lobbying (Brady et al., 1999; Kotler-Berkowitz, 2005; Verba et al., 1995). Political expertise and gaining political information takes places within informal social networks, more specific; the frequency of political interactions in ones network and the size and intensiveness are important factors even when taking individual characteristics and organizational involvement into account (La Due Lake and Huckfeldt, 1998: 581). The latter implies that not all social networks facilitate political participation, only those that are political relevant (not workers clubs that only discuss sports) (La Due Lake and Huckfeldt, 1998).

Here, we are particularly interested in the effect of bonding versus bridging social capital on political participation. However, we found little evidence on this relationship. An unpublished American study found that for whites both bonding and bridging social capital (measured by church attendance and social activism) are beneficial to formal political participation (voting). However, for blacks in the same survey only bonding social capital (church attendance) contributed to voting participation (Liu et al., 2008). The Dutch researchers Fennema and Tillie (1999; cf. Jacobs and Tillie, 2004; Peters, 2010) come to similar outcomes with regards to electoral behaviour of ethnic minority groups in Amsterdam. Fennema and Tillie observe that in three subsequent elections Turkish-Dutch residents of Amsterdam have a higher electoral turnout than other minority categories. They argue that these differences cannot be explained by differences in formal political rights. In the Netherlands, both citizens and non-citizens (at least when they live in the Netherlands for at least five years) have the right to vote in local elections. Fennema and Tillie explain the higher electoral turnout of Turks in Amsterdam by their degree of civic mindedness. The Turkish community has more migrant organizations and board members of these organizations appear to participate relatively more in several of these organizations (the authors speak of interlocking directorates in a ´network of secondary associations´) there appears to be a better breeding ground for political participation.

Fennema and Tillie (1999) do not use Putnams phrase bonding social capital, but since these organisations in the Amsterdam-Turkish community are gene-rally ethnically homogeneous we may rephrase their research finding as the more bonding social networks, the more political participation – which contradicts our hypothesis that bridging social contacts facilitate political participation. Fennema and Tillies Amsterdam research was later replicated in several European cities with various results. In some cities, there appeared to be no clear and positive effect of ethnic membership on political involvement. In other studies, informal networks (friendships) appeared to be more important in explaining voting behaviour rather than membership of organisations. In sum, in the replication studies the relationship between ethnic civic communities and political participation is not as clear as in Fennema and Tillies original study (Jacobs et al., 2004; Koopmans, 2004; Togeby, 2004; cf. Peters, 2010: 21-14). Another limitation of Fennema and Tillies original study is that they have not examined their argument using individual data about the extent of social capital and its relationship with political participation as we will do in this analysis.

In our analyses, civic participation is defined as participation in voluntary organizations such as environmental organizations and other non-profit or voluntary organizations. Despite Putnams concern about the collapse of the community in modern societies, there is still evidence about substantial and stable civic participation. Recent Dutch research found that more than 40% of the Dutch population participated in some kind of voluntary work. American research found even higher participation rates, more than in any other European country (Dekker and De Hart, 2009: 22). In Belgium, Elchardus et al. (2000), also found substantial participation in voluntary activities. In the United States, participation rates are even higher. Wilson (2000: 217) cites a 1998 Gallup survey reporting that more than 50% of the population volunteered in the previous year. All these data suggest that participation in voluntary associations is far from outdated, although some authors observe a certain shift from traditional voluntary work (static, organised by semibureaucratic organisations, ideological or religious motivated) to more contemporary forms of civic participation (more pragmatic and dynamic, often local and informal organised, motivated by specific occasions and feelings). Political participation is defined in terms of formal political participation, that is: participation in local or national elections. Bridging social networks will be defined as the share of social contacts respondents have outside their own family, their own local community (district) and their own ethnic community. We hypothesize that more bridging social contacts result in more civic and political participation.

III. MEASUREMENT

The central independent variables in the analyses relate to the size and composition of the social networks of the respondents. We asked respondents three questions about their informal social contacts: With how many people, who do not belong to your household and which are important for you, do you spend your free time in total?; How many people, who do not belong to your household, would you ask for advice or would you listen to in relation to important changes on personal, professional or family level?; and How many people, who do not belong to your household, are important in another way which is not mentioned yet?

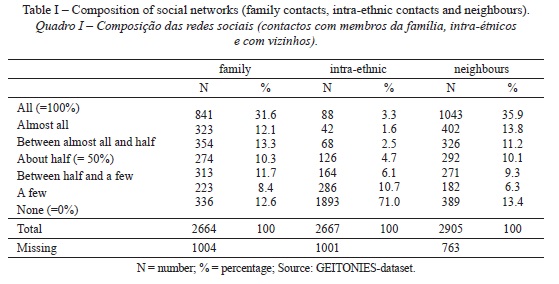

The total number of people named on these three questions is summed up to assess the size of the social network of respondents. Subsequently, we asked the respondents how many of these people they named were family, how many of them are neighbours or live in the same district, and how many of them belong to the same ethnic community. The response options on these questions were: 1 = all, 2 = almost everybody, 3 = between almost all and half, 4 = about half, 5 = between half and a few, 6 = a few, 7 = none, 8 = do not know (missing).

Based on these answers, we created three variables: 1) Share of the social network which is family, 2) Share of the social network living in the neighbourhood of the respondent, and 3) Share of the social network which is intra-ethnic.

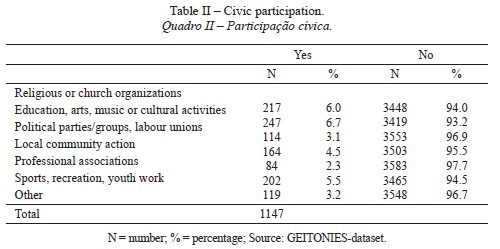

The first dependent variable is civic participation. The respondents were asked whether or not they participated in voluntary work in several domains: in religious or church organizations; in education, arts, music or cultural activities; in political parties or labour unions; local community organizations; professional associations; in sports, recreation or youth work; or in other voluntary work. On each question respondents could answer Yes (=1) or No (=0). In the analyses, we created a variable civic participation with three values: 0 = no voluntary work (total score 0), 1 = one type of voluntary work (total score 1); and 2 = two or more types of voluntary work (total score at least 2).

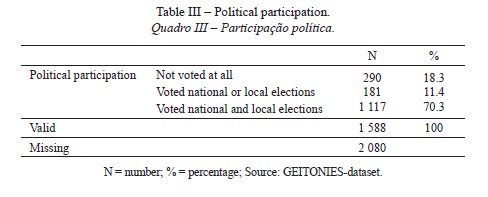

The second dependent variable is political participation. Respondents were asked if they participated in the last national and in the last local elections (in the country of residence). Respondents with an immigrant background could also indicate they were not eligible to vote in the country of residence. Respondents who were not eligible to vote were excluded from the analyses. We created the variable political participation with three values: 0 = not voted at all; 1 = voted once (either in the last national or in the last local elections); and 2 = voted twice (in both the last national and local elections).

Given the nature of the dependent variables (nominal) we are bound to use multinomial logistic regression models in our analyses.

IV. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

Our central research question in this article is whether and to what extent the size and composition of informal social networks of people are of influence on the degree of civic and political participation. More specifically, since this research is focused on interethnic contact in cities and the consequences of interethnic contact, we are interested in the possible relationships between interethnic contacts on the one hand and civic and political participation on the other hand. Are respondents with more interethnic contacts more involved in civic and political participation or not? However, we start with the descriptive statistics of our analyses.

1. Descriptive statistics

We start the results of our study with a description of the most important dependent and independent variables. Table I shows the composition of the social networks of our respondents. After the size of social networks was established, respondents were asked what share of their network consisted of family members, members of their own ethnic community and neighbours.

Concerning the share of family members in the social networks of respondents, table I shows that almost 32% of the respondents have a total family based social network. Almost 13% of the respondents did not have any family members in their social networks. The next column shows the share of intra-ethnic contacts in the networks of respondents. We see that a large majority of the respondents (71%) did not have an intra-ethnic network at all, which represents all native respondents since they were conceptually not able to have intra-ethnic contacts. The third independent variable in this study is the share of neighbours in the social network. Where almost 13.4% of the respondents do not have any neighbours and neighbourhood residents in their social network, over 35.9% of the respondents have a social network with only people from their own neighbourhood.

Table II shows the frequencies of participation in voluntary work. More than 1,100 respondents participated in at least one domain of voluntary work, which also means that 75.1% of the respondents did not participate in any kind of voluntary work (N= 3558).

Table III describes the distribution of voting behaviour of all respondents. Over 70% of the respondents, at least those who answered these questions and were eligible to vote, voted both in the national and local elections. However, more than half of the respondents did not answer the questions about voting or were not eligible to vote.

2. Civic participation

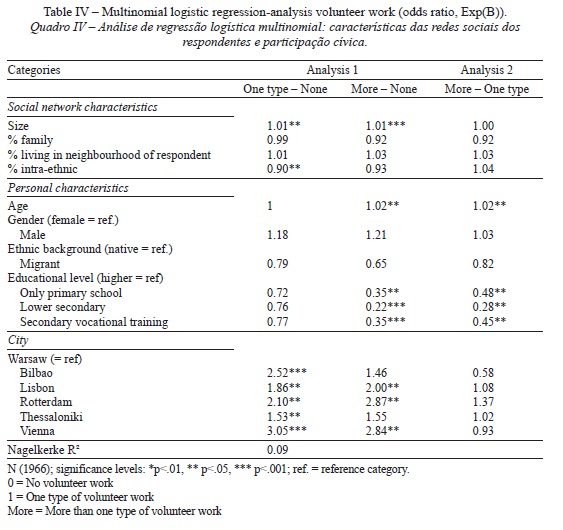

We start our research findings with civic participation, more specifically with participation in (organized) voluntary work. In our survey we asked respondents about their participation in several kinds of voluntary work. Using this information we constructed a dependent variable with three categories: No voluntary work, voluntary work for one organisation, voluntary work for two or more organisations. We used multinomial logistic regression analysis to examine the relationship of civic participation with several dependent variables (size and composition of the social network, various personal characteristics and research location). In our tables, we only present the final models containing all variables. Table IV gives the outcomes of the first multinomial logistic regression analysis that estimates the odds that respondents participate in one or in two or more types of voluntary work, in comparison to the odds that they do not participate in any voluntary work (reference category). The second analysis (also in table IV) estimates the odds that respondents participate in at least two types of voluntary work, in comparison to the odds that they participate in only one type of voluntary work (reference category).

If we start with the odds that respondents participate in one type of voluntary work (first column), we see that the coefficient of network size indeed has a significant value. This means that respondents with larger social networks are more inclined to participate in one type of voluntary work (compared with the chance of not participating) than respondents with smaller social networks. This confirms the expectations in the literature. People with larger social networks have higher chances to be asked for voluntary work and participate more. The coefficient of the share of intra-ethnic contacts also has a significant value, but this time the odds ratio is smaller than 1. This means that respondents with relatively speaking more intra-ethnic social contacts are less inclined to participate in one type of voluntary work (again compared with the chance of not participating at all) than respondents with less intra-ethnic contacts. Thus, there appears to be a negative relation between the two factors: respondents with more intra-ethnic contacts in their social networks have 10% less chance to participate in voluntary work than respondents with less intra-ethnic (thus relatively speaking more interethnic) contacts in their social networks. This may be an important finding: ethnic homogeneous social networks appear to be related to lesser participation in one type of voluntary work. However, this does not say anything about causality. It might as well be that people participating in voluntary work obtain more heterogenic social networks.

The coefficients of all other social network and personal characteristics show no other significant values. This means, they appear not to be of influence on the chances that respondents are participating in one kind of voluntary work (compared with the chances of not participating). However, the coefficients of the various research locations (cities) have large and significant values. Respondents in Warsaw (the reference category) appear to be least inclined to participate in one type of voluntary work (compared with the chance of not participating). Respondents in the other cities are between 1.5 (Thessaloniki) and more than 3 times as often (Vienna) likely to participate in one type of voluntary work (compared with the chances of not participating) than respondents in Warsaw. Unfortunately, our analyses cannot shed any light on possible explanations of these huge differences in outcomes in the various research locations.

The second column of table IV shows the odds that respondents participate in two or more types of voluntary work, compared with the chances they do not participate at all. Again, the coefficient of network size has a significant value with an odds ratio larger than 1. This means that respondents with larger social networks also participate more often in two or more types of voluntary work (compared with the chance of not participating) than respondents with smaller social networks. Thus in general, there appears to be a positive relationship between network size and participating in voluntary work. Respondents with larger social networks participate more often in voluntary work (compared to the changes of not participating) than respondents with smaller social networks. Here, the coefficients of the various measures of the composition of social networks do not show any significant values.

The composition of social networks (in terms of proportion of family, neighbourhood contacts or intraor interethnic contacts) is not related to the odds of participating in two or more types of voluntary work (compared to the chances of not participating at all).

When looking at the coefficients of the various personal characteristics, we see quite a few significant values. Firstly, age appears to be related to the chance of participating in two or more types of voluntary work. Older respondents more often participate in two or more types of voluntary work (compared to the chances of not participating) than younger respondents. The coefficients of the different educational levels also show significant values. The odds ratios are smaller than 1. This means that respondents with lower educational levels are less likely to participate in two or more types of voluntary work (compared to the chances of not participating) than respondents that have finished a higher education (reference category). Here again, there are large and significant differences between respondents in the different research locations. Respondents in Lisbon, Rotterdam and Vienna are 2 to almost 3 times as likely to participate in two or more types of voluntary work (compared to the chances of not participating) than respondents in Warsaw (reference category). The outcomes in Bilbao or Thessaloniki do not differ significantly from the out-comes in Warsaw. Again, we can only guess what the explanation of these differences may be. A possible reason may be that countries like Austria and the Netherlands have a long standing tradition of voluntary association, whereas other countries (like Poland) do not have these traditions. Another possible explanation may be that in countries like Poland, Spain and Greece informal support is more important, whereas our research focused on formal civic participation. Wilson and Musick (1997) examined the relationship between giving informal support and participating in voluntary work, but found no relationship between the two.

The third and last column of table IV show the outcomes of a separate logistic regression analysis that compares the outcomes of respondents that participate in two or more types of voluntary work with the outcomes of respondents who participate in only one type of voluntary work (reference category). The coefficients of the various social network characteristics do not show any significant values. This means that neither the size nor the composition of social networks seems to be related to the chances of participating in two or more types of voluntary work (compared to the chance or participating in only one type). Of the personal characteristics, only the coefficients age and educational level show significant values. Older respondents appear to be more likely to participate in two or more types of voluntary work (com-pared to the chance of participating in only one type) than younger respondents. Also respondents with a higher education (reference category) are more likely to participate in two or more types of voluntary work (compared to the chance of participating in only one type) than lower educated respondents. Finally, there are no differences in the odds of participating in two or more types of voluntary work (compared to the odds of participating in only one type) between respondents in the various research locations.

The general conclusion may be that, as expected and in line with Putnams argument, there is a positive relation between the size of social networks and civic participation in a sense of participating in voluntary organisation. The larger the informal social networks, the more chance respondents participate in one or more voluntary organisations. Contrary to our expectations, the composition of social networks seems hardly relevant for civic participation. Bonding social networks (in a sense of more family-based, more intra-neighbourhood or more intra-ethnic contacts) are hardly related to more or less civic participation. The only exception here is that respondents with more intra-ethnic contacts participate less often in one voluntary organisation (compared to not participating at all) than respondents with less intra-ethnic (but more interethnic) social contacts. Personal characteristics of respondents are only related to participating in more than one voluntary organisation. Older respondents more often participate in several voluntary organisations than younger respondents. The same goes for respondents with the highest educational level compared to all respondents with lower educational levels. A final remarkable outcome may be that ethnic background (having an immigrant background or not) appears not to be related to civic participation. Respondents with an immigrant background do not have smaller or larger chances to participate in voluntary organisations than native respondents.

3. Political participation

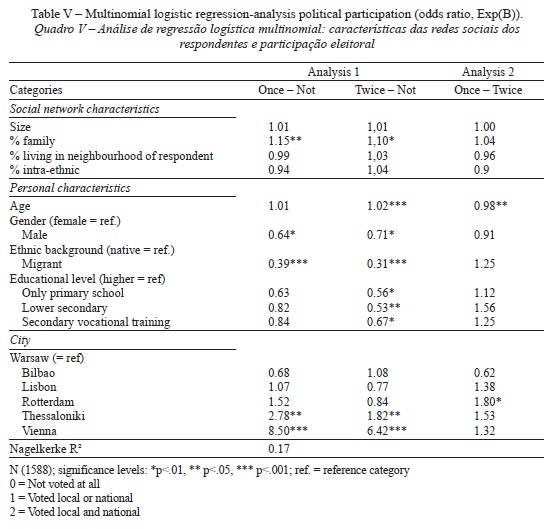

The other general topic in our analyses is political participation. Political participation is measured with the survey question whether or not respondents participated in the previous national or local elections (as far as they were eligible to vote). Again, we created three possible answer categories. Either respondents did not participate in any election, or they participated in only one election (national or local), or they participated in two elections (both local and national). Respondents who were not eligible to vote (mainly respondents with an immigrant background) were excluded from the analysis. In the analyses, we used the answers of 1105 native respondents and 483 respondents with an immigrant background. Again, we had to use multinomial logistic regression analysis to examine possible relationships between political participation (voting behaviour) and the various independent variables. Table V presents the outcomes of two separate logistic regression analyses.

The first analysis estimates the chances of respondents to have voted only once respectively twice in the last local or national elections, compared to the chances of having not voted at all. The second analysis estimates the chances of respondents to have voted both in the last local and national elections, compared to the chances of having voted in only one of both elections.

The first column of table V compares the outcomes of respondents who voted only once with the outcomes of respondents who did not vote at all. The social network characteristics hardly seem to be related to voting behaviour. For respondents with larger social networks, with more intra-neighbourhood contacts and with more intra-ethnic contacts the odds of having voted once (compared to not have voted) are not larger or smaller than for respondents with smaller social networks, and with less intra-neighbourhood or less intra-ethnic networks. The only exception is the share of family members in the social network. The coefficient of this factor has a significant value with an odds ratio larger than 1. This means that respondents with relatively more family members in their social network have a higher chance to have voted once (compared to not have voted at all) than respondents with less family members in their social network.

When looking at the personal characteristics of respondents, we see significant values for the coefficients of gender and ethnic background. In both cases, the odds ratios are smaller than 1. This means that males have smaller chances of having voted once (as compared to not have voted) than females. The same goes for respondents with an immigrant background. They also have smaller chances of having voted once (compared to not have voted) than native respondents in any of the six cities (the reference category). Remarkably, the coefficients of educational level are not significant. This means that, contrary to the findings of many other studies, educational background in our survey appears not to be relevant for the chances of respondents to have voted once (compared to not have voted). Finally, we see large differences in the outcomes between the different cities. There seems to be no difference in voting behaviour between respondents in Warsaw (reference category), Bilbao, Lisbon, and Rotterdam. However, respondents in Thessaloniki and particularly those in Vienna have much higher chances to have voted once (compared to not have voted) than respondents in the other four cities. A possible explanation may be that, of the six cities participating in the research, Vienna and Rotterdam have the highest shares of naturalized immigrants in the sample. On the other hand, we included only respondents in the analyses who were eligible to vote. In Vienna, voter participation is generally high (in international comparison), although lower among naturalized migrants.

The second column of table V compares the outcomes of respondents who voted twice with the outcomes of respondents who did not vote at all. The outcomes are not very different from the previous comparison. Of the social network characteristics, again, only the coefficient of the share of family members has a significant value (odds ratio larger than 1). Respondents with relatively more family members in their social network have a higher chance to have voted twice (compared to not have voted at all) than respondents with less family members in their social network. But besides that, neither the size nor the composition of the social network appears to be related to voting behaviour.

With regard to the personal characteristics, we see more significant values than in the previous comparison. Like before, we see that males have smaller chances to have voted twice (compared to not have voted) than female respondents. The same goes for respondents with an immigrant background compared to native respondents. All in all, we can conclude that both males and respondents with an immigrant background more often belong to the category non-voters than females or native respondents. Here we also see a significant value for the coefficient of age. With an odds ratio larger than 1, this means that older respondents have larger chances to have voted twice (compared to not have voted) than younger respondents. Also the coefficients of educational level are significant. As the odds ratios are all smaller than 1, this means that respondents with lower educational levels have smaller chances of having voted twice (compared to not have voted) than respondents with the highest educational level (the reference category). Finally, we see the same differences in outcomes between the various cities. The odds of having voted twice (compared to not have voted) are higher for respondents from Thessaloniki and (particularly) from Vienna than for respondents from the other four cities.

The third and last column of table V gives the outcomes of a separate logistic regression analysis comparing the outcomes of respondents who have voted once with the outcomes of respondents who have voted twice (the reference category). Only very few outcomes are worth mentioning. Here again, we see that none of the social network characteristics appear to be related in any way to how often respondents have voted. Of the personal characteristics only age seems to be important. Older respondents have smaller chances to have voted once (compared to have voted twice) than younger respondents. With regard to the various research locations, only the coefficient of Rotterdam has a significant value. The odds ratio is larger than 1, which means that Rotterdam respondents have higher chances to have voted once (compared to have voted twice) than respondents in all other research locations. The reason may be that in the Netherlands, non-Dutch residents are eligible to participate in local elections, but not in national elections. As a result, more Rotterdam respondents have voted only once (and not twice) than respondents in the other cities.

The most remarkable outcome with regard to political participation (having voted in local or national elections versus not having voted) is that we found no significant relations with the size and composition of social networks. Following Putnam (2000), we expected a positive relation between network size and political participation (larger networks, more political participation). With our data, we cannot confirm this hypothesis. Neither did we find a significant relationship between the composition of social networks, particularly the share of intra-ethnic versus the share of interethnic social contacts, and voting behaviour. We therefore cannot confirm our hypothesis that more bridging social networks, in particular more interethnic contacts, result in more political participation. On the other hand, our study also rejects Fennema and Tillies (1999) finding that intra-ethnic social contacts (in their case: the number of ethnically-bound organisations present in the city) contribute to higher political behaviour. In fact, we did not find any relationship between the ethnic composition of social networks and voting behaviour of respondents. To be sure, we estimated the models again for only native respondents (N= 1105) and for respondents with an immigrant background (N= 483). Fennema and Tillies argument is, of course, only about the latter category. However, also when looking only at respondents with an immigrant background we did not find a significant relationship between the ethnic composition of social networks (intra-ethnic versus interethnic contacts) on the one hand and voting behaviour on the other hand. As far as our outcomes can explain political participation, this is primarily related to various personal characteristics of respondents. Males less often voted once or twice than females. The same goes for respondents with an immigrant background. Apparently, men and respondents with an immigrant background more often belong to the category non-voters than women or native respondents. Furthermore, older respondents and respondents with the highest educational level have higher odds of having voted twice (compared to not have voted at all) than younger respondents and respondents with lower educational levels. Finally, we saw some variation in the outcomes in different cities. Respondents of Thessaloniki and (particularly) Vienna have much higher chances of having voted once or twice than respondents from the other cities. Unfortunately, with the current analysis we are unable to explore possible reasons for this variation in outcomes between the cities.

V. CONCLUSION

This article examined possible relationships between the size and composition of informal social networks of residents of six European cities on the one hand and their civic and political participation – measured by their participation in voluntary work and in national or local elections – on the other hand. Following Robert Putnam (2000), we expected a positive relation between the two. People with larger social networks participate more. Since our research project focused on interethnic social contacts in urban contexts, we also expected people with bridging social contacts to participate more than people with predominantly bonding social contacts. Finally, we expected that higher educated people participate more than people with lower educational levels.

With regard to the first hypothesis, we found that network size is indeed positively related to participation in voluntary work. People with larger social networks participate more. An obvious explanation may be that people with larger social networks have higher chances to be asked for voluntary work and participate more. However, network size in our survey appeared not to be related to political participation. People with large social networks do not vote more or less often than people with less social contacts. This is a remarkable finding, various studies cited previously found that social network size is positively related to political participation. All in all, the first hypothesis is partially confirmed: there is positive relation between network size and civic participation, but there is no relation with political participation.

Besides the size of social networks, previous research also found a positive relation of educational level and participation. Our second hypothesis therefore was: higher educated people participate more than lower educated people. This hypothesis is confirmed in both analyses: higher educated people participate more both civically and politically than lower educated people. More specifically, higher educated people tend to participate more in at least two types of voluntary work, where lower educated people tend to participate more in one type of voluntary work. And higher educated people tend to vote more often twice (both nationally and locally) than lower educated people.

Our third hypothesis relates to the composition of social network. We expected people with bridging social networks to participate more than people with bonding social networks. We measured the composition of the social networks of respondents in three different ways: the share of local residents in the social network versus the share of people living elsewhere, the share of family versus the share of friends and acquaintances in the social network, and the share of intra-ethnic contacts versus the share of interethnic contacts in the social network. However, we found only few significant relationships between various dimensions of the composition of the social network and civic and political participation. Firstly, people with more intra-ethnic contacts are more active in voluntary organizations if they participate in voluntary work than people with more interethnic contacts. The reason may be that people with more intra-ethnic contacts are also more active in social organisations from their own ethnic community (but we did not ask questions about the back-ground of the voluntary work they did). Secondly, we found that people with more family-based social network tend to vote more often than people with more friends and acquaintances in their social network. Thus, as far as we found any relationship between the network composition and civic and political participation, we found that people with more bonding social networks participate more often than people with more bridging social networks.

We did not find any relationship between intra-ethnic versus interethnic social contacts and political participation. We expected that people, particularly people with an immigrant background, with more interethnic social contacts to be more politically involved than people with a predominantly intra-ethnic social contacts. On the other hand, we cited Fennema and Tillie (1999) who found the contrary. They attributed the higher electoral turnout of voters with a Turkish ethnic background in Amsterdam compared to voters of other minorities to the higher degree of civic mindedness of the Turkish community. As there are relatively more (mostly intra-ethnic) Turkish organisations in Amsterdam, there appears to be a better breeding ground for political participation. However, our outcomes do not support either the more liberal expectation that interethnic contacts are a breeding ground for political involvement or Fennema and Tillies position that intra-ethnic social networks contribute to more political participation. As far as our outcomes explain political participation, this is primarily related to personal characteristics of respondents: males voted less often than females; respondents with a migrant background voted less often than native respondents (even when the migrants were eligible to vote); and higher educated respondents more often voted twice (as compared to not voted at all) than lower educated respondents.

A final comment relates to the six research locations of the GEITONIES-survey. In particular, the Austrian capital Vienna stood out as a city with high levels of both civic and political participation. Also in the cities of Bilbao and Rotterdam, civic participation was more than average. In Thessaloniki, political participation (voting) was higher than in the other research locations. On the basis of this survey, we cannot give an adequate explanation of these differences between the six cities participating in the GEITONIES-survey. It is clear, however, that these different out-comes with regard to voting do not result from differences in voting rights in the six countries because we only included respondents into the analyses who were eligible to vote. Vienna (and Austria in general) is known to have a long standing tradition of clubs, civic associations and voluntary work that goes back to the times of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. Also voter participation is known to be generally high in Vienna, although higher among native citizens than among naturalized immigrants.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers of Finisterra and Dr. Ursula Reeger (Institute for Urban and Regional Research, Austrian Academy of Science) for their helpful comments on a previous version of this study.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bourdieu P (1986) The forms of capital. In Richard-son J (ed.) Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. New York. Greenwood: 241-258. [ Links ]

Brady H, Schlozman K, Verba S (1999) Prospects for participants: rational expectations and the recruitment of political activists. American Political Science Review, 93(1): 153-68. [ Links ]

Council of Europe (2004) A new strategy for social cohesion. Revised strategy for Social Cohesion. [ Links ]

Elchardus M, Hooghe M, Smits W (2000) Tussen burger en overhead. Een onderzoeksproject naar het functioneren van het maatschappeli-jk middenveld in Vlaanderen. Brussels: Vrije Universiteit Brussel (TOR Rapport 2000/5)

Dekker P, [ Links ] De Hart, J (eds) (2009) Vrijwilligerswerk in meervoud. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau. [ Links ]

Fennema M, Tillie J (1999) Political participation and political trust in Amsterdam: civic communities and ethnic networks. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 25(4): 703-726. [ Links ]

Jacobs D, Tillie J (2004) Introduction: social capital and political integration of migrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30(3): 419-427. [ Links ]

Jacobs D, Phalet K, Swijngedouw M (2004) Associational membership and political involvement among ethnic minority groups in Brussels. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30(3): 419-427. [ Links ]

Koopmans R (2004) Migrant mobilization and political opportunities: variation among German cities and a comparison with the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30(3): 449-470. [ Links ]

Kotler-Berkowitz L (2005) Friends and politics: linking diverse friendship networks to political participation. In Alan Z (ed.) The social logic of politics: personal networks as contexts for political behavior. Philadelphia, Temple University Press: 152-170. [ Links ]

La Due Lake R, Huckfeldt R (1998) Social capital, social networks, and political participation. Political Psychology, 19(3): 567 (+18). [ Links ]

Lim C (2008) Social networks and political participation: how do networks matter? Social Forces, 87(2): 961-982. [ Links ]

Liu B, Wright Austin S, Weber L (2008) Social capital and voting participation: a racial perspective. [Accessed on 20-12-2012] web. polisci.ufl.edu/documents/rsp/austins-jan2008.doc

Peters L (2010) The big world experiment. [ Links ] The mobilization of social capital in migrant communities. Amsterdam: UVA. [ Links ]

Portes A (1998) Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24: 1-24. [ Links ]

Putnam R D (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. New York. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks. [ Links ]

Putnam R D (1995) Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6: 65-78. [ Links ]

Putnam R D (1993) Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Togeby L (2004) It depends

. How organizational participation affects political participation and societal trust among second-generation immigrants in Denmark. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30(3): 509-528. [ Links ]

Verba S, Schlozman K, Brady H (1995) Voice and equality: civic voluntarism in American politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Wilson J (2000) Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26: 215-40. [ Links ]

Wilson J, Musick M (1997) Who cares? Towards an integrated theory of volunteer work. American Sociological Review 62(5): 694-713. [ Links ]

Received: October 2012. Accepted: March 2013

FUNDING

This research has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2011) under grant agreement nº 216184 (GEITONIES PROJECT).