Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

Print version ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.96 Lisboa June 2013

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Neighbourhood integration in european multi-ethnic cities. Evidence from the Geitonies project

Integração ao nível do bairro em cidades europeias multi-étnicas. Resultados do projecto GEITONIES

Maria Lucinda Fonseca1 Jennifer McGarrigle2 Alina Esteves3

1 Full Professor in the Institute of Geography and Spatial Planning and researcher at the Centre for Geographical Studies, University of Lisbon. E-mail: fonseca-maria@campus.ul.pt

2 Researcher at the Centre for Geographical Studies, University of Lisbon. E-mail: jcarvalho@campus.ul.pt

3 Assistant professor in the Institute of Geography and Spatial Planning and researcher at the Centre for Geographical Studies, University of Lisbon. E-mail: alinaesteves@campus.ul.pt

ABSTRACT

This special issue of Finisterra is based on the findings of the GEITONIES project, and intends to shed some light on questions relating to ethnic diversity, social relations and participation in urban settings. The research was conducted in 6 European cities: Lisbon, Bilbao, Thessaloniki Rotterdam, Vienna and Warsaw and the neighbourhood context was adopted as the field of research. A random survey was implemented to 3600 residents in 18 neighbourhoods in the six cities. The papers included in this special issue of Finisterra – Revista Portuguesa de Geografia, focus on processes of change and social relations at the neighbourhood level and stress the role of place and time in the development of positive inter-group contacts, representations and integration.

Keywords: Inter-ethnic relations, neighbourhood, diversity, European cities.

RESUMO

Integração ao nível do bairro em cidades europeias multiétnicas. Resultados do projecto GEITONIES. Este número especial da Revista Finisterra apresenta alguns resultados do projecto GEITONIES e tem como objectivo debater questões relacionadas com a diversidade étnica, as relações sociais e a participação cívica e política da população imigrante e não-imigrante em meios urbanos. A investigação decorreu em 6 cidades europeias: Lisboa, Bilbau, Salónica, Roterdão, Viena e Varsóvia, sendo o bairro a escala de análise adoptada para a investigação. Por conseguinte, efectuou-se um inquérito, aplicado a uma mostra aleatória de 3600 indivíduos (imigrantes e nativos) residentes em 18 bairros multiétnicos das seis cidades. Os artigos incluídos neste número especial da Finisterra – Revista Portuguesa de Geografia centram-se nos processos de mudança e nas relações sociais ao nível do bairro, e salientam o papel do lugar e do tempo no desenvolvimento de contactos interétnicos, de representações positivas e da integração nos territórios de residência.

Palavras-chave: Relações interétnicas, bairro, diversidade, cidades europeias.

RéSUMÉ

Intégration de voisinage dans des villes Européennes Pluri-ethniques. Résultats du projet GEITONIES. Ce numéro spécial de la revue Finisterra présente quelques résultats du projet GEITONIES qui a comme objectif de débattre des questions relatives à la diversité ethnique, aux relations sociales et à la participation civique et politique de populations immigrées et autochtones en milieu urbain. La recherche a eu lieu dans six villes Européennes: Bilbao, Lisbonne, Rotterdam, Salonique, Varsovie et Vienne. Létude sest déroulée à léchelle du quartier. On a lancé une enquête par questionnaires qui a porté sur un échantillon aléatoire de 3600 individus (immigrés et autochtones), résidents de 18 quartiers pluri-ethniques des six villes concernées. Les articles de ce numéro spécial de Finisterra-Revista Portuguesa de Geografia sont principalement orientés sur les processus de changement des relations sociales au niveau du quartier. On sy est soucié de lenvironnement géographique et des périodes de contacts inter-ethniques qui peuvent jouer dans les représentations dintégration de ces lieux de résidence et soulignent le rôle du lieu et du temps dans le développement de contacts inter-ethniques.

Mots-clés:Relations inter-ethniques, quartier, diversité, villes Européennes.

I. INTRODUCTION

In recent times the accommodation of difference has been challenged and scrutinized across European countries. Whilst the increasing diversity of European societies, especially in ethnic, cultural and religious terms, has at times been celebrated, more often it has given credence to fears that society is becoming more socially fragmented. In turn, models of integration have been subjected to scrutiny. The French model has been criticised for its blindness to inequality and exclusion along ethnic lines, whilst the multicultural models once prized for their cultural-sensitivity and recognition have been criticised for privileging group rights and preserving difference at the expense of cohesion and shared societal norms and values. Despite these concerns related to parallel lives and social fragmentation, there is a scarcity of empirical data to inform these debates. As stated in the introductory note, this special issue of Finisterra is based on the findings of the GEITONIES project, and intends to shed some light on these debates.

The theoretical approach of the GEITONIES project is aligned with the perspective of interculturalism. The focus moves away from the promotion of the specific cultural features of each ethnic group, as in multiculturalism, to the promotion of positive interaction among groups. Departing from the cultural diversity of contemporary metropolises and assuming that culture is dynamic, the construction of spaces of intercultural dialogue is seen as crucial to safeguard social cohesion. Sandercock(2004) contends that interculturalism implicitly refers to two rights: the right to difference and the right to the city. From this perspective, regardless of ethnic background, people have equal rights in shared public space and full participation in the public affairs of the urban residential environment, not just de jure (through legal provisions and access to political participation) but also de facto (in the practical situations of everyday life).

Focusing on social relations at the neighbourhood level and stressing the role of place and time in the development of positive inter-group contacts and representations, the GEITONIES project aimed to identify key factors that hinder or promote the development of a cohesive society. In light of this, attention is paid to the development of interdependencies among people in a defined social and spatial environment. Cultural interaction is considered to take place at two analytical levels: the micro and the median level. The micro level includes the more or less consciously motivated interaction between individuals, as well as their attitudes towards each other and towards the institutions present within subgroups and the local social environment as a whole. The median level concerns the development of institutions within (sub) groups, institutional relations between groups and institutions in the broader social environment. Also, at the median level, we can observe a variety of initiatives taken collectively by actors to counteract constraints or make the most of opportunities at the macro level. These developments are the product of larger socioeconomic trends in society or of political decision making. As a general rule, people do not have much command over macro-level process. A slowing/booming economy, or global geopolitics, such as the impact of 9/11 and its aftermath, are examples of such macro level influences.

The methodological design of the GEITONIES project focuses on the local level, but the theoretical scope is not limited to the micro level. Certainly, any satisfactory theoretical account should address all three levels.

II. THE GEITONIES SURVEY: SAMPLE DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION

1. General considerations

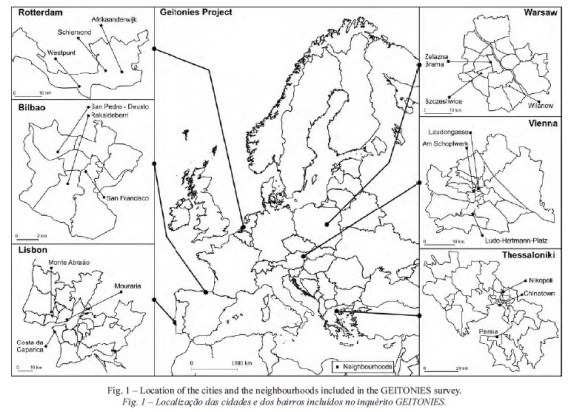

The GEITONIES questionnaire has a longitudinal design, focusing on the life course events of the respondents across several domains before and after they moved to the neighbourhood of residence. The main topics include the following: socio-demographic information on the respondent and her/his parents; education; language proficiency; migration history; household composition; legal status; economic activities and income statuses; current and past social networks; contacts with neighbours; civic participation; neighbourhood attachment and satisfaction; use of local public space; and general attitudes. A key objective of the project was to understand modes of interethnic coexistence among different social and ethnic groups at the urban local level, thus, the target population of the survey included both the population with an immigrant and native background, living in the selected neighbourhoods of the case-study cities: Rotterdam, Vienna, Lisbon, Bilbao, Thessaloniki and Warsaw (fig.1).

The concept of immigrant background adopted in the GEITONIES survey refers to a person with, at least, one parent born outside the country of residence. Similarly, a person is of native background when both parents were born in the country of residence. As is evident from these definitions, the variable place of birth is central to this division and was chosen over nationality given the different criteria for acquiring citizenship in the six countries included in the project. Moreover, given different data collection processes data was not universally available on ethnic group. The assessment of different modes of interethnic coexistence and the evaluation of interaction between diverse groups of different ethnic background (intercultural communication, dialogue, exchanges), central issues of the project, are answered using this basic division among respondents.

Thus, the diverse migration history of each of the six countries participating in the GEITONIES project posed some challenges in the operationalization of the definition of immigrant background. Indeed, in countries like Portugal with a recent colonial pasti, the presence of people whose parents, of European ancestry, were born in former colonies makes them potential respondents of migrant descent whose relations and interactions with other Portuguese citizens, also of European origin, are considered interethnic. As such, the often difficult processes of reintegration into Portugal of return migrants and the potential impact on their children is taken into consideration.

Another challenge is posed, particularly for the Greek case study, by the political upheaval that swept Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union twenty years ago, which led to new migratory flows of co-ethnic members of historical diasporas to their home countries. The acknowledgement of a community of Soviet Greeksii and another of Albanian Greeks and privileged access to nationality based on jus sanguinis granted by the Greek state led to a remarkable presence of these citizens in the major metropolises after 1989 (Voutira, 2004). Though they fit into the category of immigrant adopted in the project, the relationships of Soviet and Albanian Greeks with native Greeks are not treated as interethnic because they are seen as both inter and intra ethnic by different actors and depending on the context (Labrianidis et al., 2010: 63). A further specificity in the Greek case is related to the fact that a number of native respondents (both parents born in the country of residence) are in fact second generation Greek returnees from Western Europe whose parents had emigrated after World War II. As stated in the Thessaloniki City Survey Report, Once more their ethnic/national origin is different from their country of birth (2010: 63). In order to overcome this bias, the Greek team combined data on the actual ethnic origin of the respondents and his/her country of birth, prioritizing the information on origin (Labrianidis et al., 2010: 63).

2. Sampling

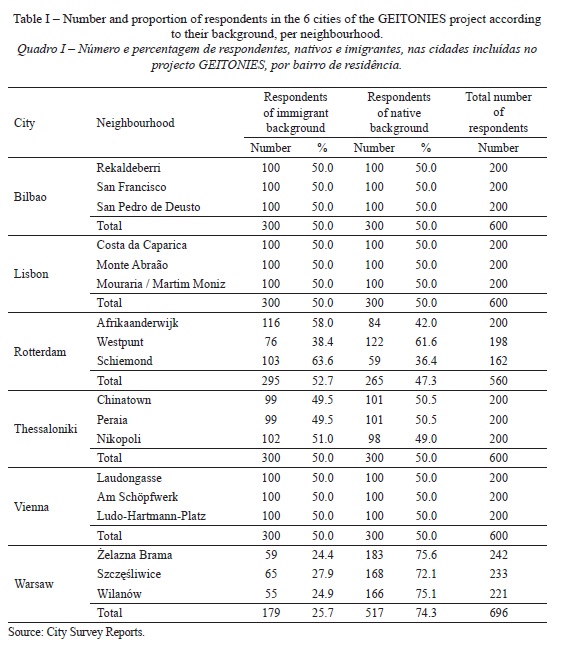

In order to ensure that the data was robust and representative, a random sampling method was implemented. The planned sample size was 200 in each neighbourhood, that is, 600 interviews per city and 3,600 interviews in total. The target population comprised inhabitants who had resided in the neighbourhood for at least one year and the sampling unit was the household. In Lisbon, Thessaloniki, Rotterdam and Warsaw initial fieldwork was undertaken to compile an inventory of addresses and building uses in the case study areas by enumerating all the existing households per building unit, or in the case of Thessaloniki, houses and buildings (Labrianidis et al., 2010: 18).

In Vienna and Bilbao, the local authorities provided lists of addresses rendering this part of the fieldwork unnecessary (Kolbacher et al., 2010; Setién et al., 2010). When each city had compiled its address inventory, 200 addresses were randomly selected ensuring all addresses had a non-zero chance of selection. Considering the main research goal of the project, a quota was defined of 100 individuals of immigrant background and 100 of native background. Warsaw adopted a smaller quota of 50 immigrants per area as in comparison to the other five metropolises the number and proportion of immigrants in the city is lower (Górny and Torunczyk-Ruiz, 2010).

The respondent unit was a household member, aged over 25, who had lived in the dwelling for at least one year – no upper age limit was employed. The 25 year-threshold was adopted in line with the goal to obtain retrospective information on housing careers, job mobility, friendships and other aspects. However, this was supplemented with information collected on youngsters residing in the case study areas during meetings with local key-institutional actors and in interviews with other relevant local actors. Nevertheless, further research is needed to fully understand the representations, daily practices and interactions that affect the social relations between young people from different social and ethnic groups.

With the goal of ensuring the random selection of the respondent within each household, the birthday method was adopted, that is, the household member who had most recently had a birthday was interviewed.

3. The fieldwork: duration, response rates and challenges

The fieldwork was conducted between June 2009 and October 2010; however, it commenced in each of the six cities at slightly different times and progressed at different paces due to the specific challenges encountered. The interviews were conducted on working days but also on weekends and national holidays, both in the morning, afternoon and evening, in order to increase the chance of finding potential respondents at home. After 3 unsuccessful attempts to contact a given resident it was considered a non-response and the address replaced by another one. The overall response rate varied considerably among the neighbourhoods in each city due to the features of each residential area. For example in Lisbon, in Mouraria / Martim Moniz the response rate was 60.3%, whereas in Monte Abraão it was 52.7% and in Costa da Caparica it only reached 30.7% (Fonseca et al.,2010).

Due to the small proportion of foreign citizens in Warsaw the method for reaching immigrants was modified slightly, as was the number of interviews carried out with this group. Moreover, in order to guarantee larger heterogeneity within the sample, quotas for ethnic background, age and sex were defined. Due to the difficulty encountered in accessing respondents of immigrant background, especially the Vietnamese, at home, interviewees were also recruited in public spaces, schools, associations and work places within the areas. The snowball technique was adopted in a few cases (Górny and Torunczyk-Ruiz, 2010) and the selection criteria for the interviewee remained unchanged.

Despite the effort made to reach potential respondents and improve the response rate, the sample of 100 respondents of immigrant background and 100 respondents of native background was not achieved in all of the 18 neighbourhoods. In cities like Rotterdam where fieldwork was difficult, it was neither possible to complete 600 questionnaires nor respect the quota for immigrants and natives due to the uneven distribution of the total resident population by background. In two of the Dutch case study areas the total number of questionnaires falls shorter than the 200 initially

As was mentioned previously, the quota was altered in Warsaw due to the small number of immigrants (Górny and Torunczyk-Ruiz, 2010; table I).

However, in order to compensate, more natives were surveyed than was initially planned.

With the exception of the negligible deviation in the case of Thessaloniki, the other 3 remaining cities followed the sample size and proportions between immigrants and natives that were agreed previously.

III. CONTENTS OF THIS SPECIAL ISSUE

The papers included in this special issue of Finisterra – Revista Portuguesa de Geografia , draw on the GEITONIES dataset to address questions relating to ethnic diversity, social relations and participation in urban settings.

In the first paper, Fonseca and McGarrigle conduct an exploratory analysis of different modes of conviviality and integration among residents in three multiethnic neighbourhoods in the metropolitan area of Lisbon. The authors identify five modes of neighbourhood embeddedness based on levels of integration, daily social relations and neighbourhood attachment and satisfaction. The modes identified serve to reveal the complexity involved in the study of neighbourhood embeddedness and attachment. The empirical findings conclude that despite some general tendencies, the effect the neighbourhood has on attachment is not uniform. Overall, natives are less attached to their place of residence than immigrants, likely due to immigrant support networks that have developed locally. The main compositional effect upon neighbourhood embeddedness is having a locally-based social network, suggesting that psychosocial factors are central to attachment. The importance of strong ties at the local level for neighbourhood embeddedness in Lisbon is in line with the results of previous research carried out by Kohlbacher et al., (2012), using GEITONIES data for three Viennese areas. However, contrary to many classical studies, socio-demographic characteristics proved to be of little relevance in predicting levels of attachment.

The second paper of this special issue, by Kohlbacher, Reeger and Schnell, adopts a more in-depth analysis of the spatial dimension of strong ties in the three Viennese case study areas included in the GEITONIES project. It considers the role of the neighbourhood in the formation of strong ties from three different perspectives: a) as the place where the first encounter took place, (b) as the place where strong ties currently live and (c) as a meeting place for people sharing strong ties. The empirical findings, confirming previous research results, showed that in the more deprived, inner-city, working-class area, strong ties are more often neighbourhood-based and less often interethnic. In the more affluent area, strong ties are not so strongly bound to the neighbourhood, but are more spatially dispersed.

The following paper, by Esteves and Sampaio, building on the case studies of Lisbon, Bilbao and Rotterdam analyses the influence that language proficiency has among immigrants in their ability to establish interethnic contacts and interact with the native population. The paper also relates the level of proficiency in the language of the destination country and the development of interethnic relations with other complementary factors that influence interactions between immigrants and natives (e.g. cultural proximity, level of education, socio-economic status, and length of residence in the host country).

The results obtained indicate that immigrants who speak the language of the host country fluently or as their mother tongue, for example those from ex-colonies, generally tend to interact more with natives. Nevertheless, for immigrants who do not share such strong cultural affinities, those with a higher level of second-language proficiency clearly show stronger bonds with the native population. In both cases this can also be related to individual, group or place related variables.

Van Duin and Snel conduct an exploratory analysis of the relation between the size and composition of social networks of native and immigrant respondents and the degree of civic participation in local and national elections, using GEITONIES data from the six case-study cities. The empirical findings confirm that the size of the social network is in fact related to participation in voluntary activities, but not with electoral participation. Interethnic contacts do not correspond to a higher civic or political participation. On the contrary, the results show that people with more bonding social networks participate more often than people with more bridging social networks.

Finally, the paper by Malheiros, Carvalho and Mendes contributes to present-day debates on the effects of gentrification and residential ethnic mixing on the social production of urban space in late modern societies. Building on a comparative analysis between two multi-ethnic neighbourhoods, in Lisbon (Mouraria/Martim Moniz) and in Bilbao (S. Francisco), the authors offer new evidence on some dimensions of the fragmented socio-spatial processes taking place in both areas, in a context marked by simultaneous marginal gentrification and ethnicization associated with the settlement of non-EU labour migrants. Marginal gentrifiers in Mouraria tend to promote community building, whereas gentrification in San Francisco tends to accentuate socio-spatial fragmentation. Furthermore, it seems that higher levels of interaction in public spaces (San Francisco) do not translate into higher local levels of ethnic mixing. This last issue is particularly important for the debate on urban policies, urban public space, democracy and citizenship (the right to the city).

[ Links ]

Kolbacher J, Reeger U, Schnell P (2012) Neighbourhood embeddedness and social coexistence. Immigrants and natives in three urban settings in Vienna. ISR-Forschungsbericht, Herausgegeben vom Institut für Stadt- und Regionalforschung, Heft 37. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien. [ Links ]

Kolbacher J, Reeger U, Schnell P (2010) Vienna city survey report. http://geitonies.fl.ul.pt/Publication/WArsaW%20City%20Report.pdf [Accessed 30 July 2012]. [ Links ]

Labrianidis L, Hatziprokopiou P, Pratsinakis M, Vogiatzis N (2010) Thessaloniki city survey report. http://geitonies.fl.ul.pt/Publication/WArsaW%20City%20Report.pdf [Accessed 30 July 2012]. [ Links ]

Miltenburg E, Lindo F, Tzaninis Y, Van Duin L. (2010) Rotterdam city survey report. http://geitonies.fl.ul.pt/Publication/LIsBON%20City%20Survey%20Report.pdf . [Accessed 30 July 2012].

Sandercock L (2004) Reconsidering multiculturalism. In Wood Ph. (ed.) Intercultural city reader. Comedia, Bournes Green. [ Links ]

Setién M L, Bartolomé E, Ibarrola A, Maiztegui C, Ruiz Vieytez E, Santibáñez R, Vicente T (2010) Bilbao city survey report. http://geitonies.fl.ul.pt/Publication/LIsBON%20City%20Survey%20Report.pdf. [Accessed 30 July 2012].

Voutira E (2004) Ethnic Greeks from the former Soviet Union as privileged return migrants. Espaces , Populations, Sociétés, 2004/3: 533-544.

Received: October 2012. Accepted: March 2013

FUNDING

This research has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2011) under grant agreement nº 216184 (GEITONIES PROJECT).

NOTES

i Although formally designated as overseas provinces, Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea Bissau, Mozambique, Saint Tomé and Prince, and East Timor were Portuguese colonies until 1974/1975.

ii Referred by the authorities as palinnostoundes homogeneis, which translates to repatriatingethnic Greeks (Labrianidis, Hatziprokopiou, Pratsinakis, Vogiatzis, 2010).