Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Ciência e Técnica Vitivinícola

versão impressa ISSN 0254-0223

Ciência Téc. Vitiv. vol.28 no.1 Dois Portos jun. 2013

Effect of alternative ageing systems on the wine brandy sensory profile

Efeito de sistemas alternativos de envelhecimento no perfil sensorial de aguardentes vínicas

Ilda Caldeira*1,2, A. Pedro Belchior1, Sara Canas1,2

1Instituto Nacional de Investigação Agrária e Veterinária, I.P.-Unidade Estratégica de Investigação e Serviços de Tecnologia e Segurança Alimentar - Laboratório de Enologia - Unidade de Investigação de Viticultura e Enologia. Quinta da Almoínha 2565-191 Dois Portos. Portugal.

2ICAAM - Instituto de Ciências Agrárias e Ambientais Mediterrânicas - Pólo da Mitra, Apartado 94, 7002-554 Évora, Portugal

*Corresponding author:

SUMMARY

The wine brandies, as other alcoholic beverages, must be kept for several months (minimum of six months according to the European legislation) in wooden barrels, in order to achieve the minimum quality, before its consumption. However, the high costs related to ageing in wooden barrels have lead to the search of alternative technologies, such as the use of wood fragments, in order to accelerate the ageing process. In this work, the same wine brandy from Lourinhã was used to fill wooden barrels and stainless steel tanks with wood tablets or wood staves. These three ageing systems were studied with Limousin oak wood (Quercus robur L.) and Portuguese chestnut wood (Castanea sativa Mill.), with two replicates of each modality. The brandies were evaluated by sensory descriptive analysis during a period of 30 months. Colour, olfactory and gustatory attributes, previously generated by the tasting panel, were analysed. The results showed a significant effect of the ageing system on few sensory attributes. However, the most discriminant factors were the wood botanical species and the ageing time, which affected significantly several sensory attributes. Concerning the ageing system, the brandies aged in the presence of wood tablets presented lower intensity of the attribute golden and higher intensities of the attributes topaz, greenish, toasted, flavour, complexity and persistence in comparison with brandies aged in wooden barrels. The brandies aged in the presence of wood staves presented an intermediate sensory profile. Nevertheless, the overall quality of the brandies is not affected by the ageing system. These results pointed out the interesting sensory attributes of the brandies obtained with the alternative ageing systems; therefore further research is needed in order to validate the use of these technologies in the ageing of wine brandy.

Key words: aged wine brandies, ageing, sensory profile, barrel, staves, tablets.

RESUMO

As aguardentes vínicas envelhecidas, à semelhança de outras bebidas alcoólicas, devem permanecer durante vários meses (mínimo de seis meses de acordo com a legislação europeia) em vasilhas de madeira de modo a atingirem um mínimo de qualidade, antes de serem consumidas. Neste trabalho uma mesma aguardente vínica da Lourinhã foi submetida a um processo de envelhecimento, com três formas de madeira: em vasilha de madeira; em depósito de aço inoxidável com introdução de madeira sob a forma de dominós; em depósito de aço inoxidável com introdução de madeira sob a forma de aduelas. Estes três sistemas de envelhecimento foram estudados com duas madeiras, o carvalho francês Limousin (Quercus robur L.) e o castanho português (Castanea sativa Mill.), com duas réplicas de cada modalidade. As aguardentes vínicas envelhecidas foram avaliadas por análise sensorial descritiva durante um período de 30 meses. Foram avaliados descritores sensoriais visuais, olfativos e de sabor que foram previamente gerados pelo grupo de prova. Os resultados demostraram a existência de um efeito significativo do sistema de envelhecimento num pequeno número de descritores sensoriais. Contudo, os fatores mais discriminantes foram a espécie botânica da madeira e o tempo de envelhecimento, os quais influenciaram significativamente vários descritores sensoriais. Relativamente aos sistemas de envelhecimento, verificou-se que as aguardentes envelhecidas na presença de dominós apresentaram menor intensidade no descritor dourado e intensidades mais elevadas nos descritores topázio, esverdeado, torrado, complexidade e persistência do sabor quando em comparação com as aguardentes envelhecidas nas vasilhas. As aguardentes envelhecidas na presença de aduelas apresentaram um perfil sensorial intermédio. Todavia, a qualidade global da aguardente não foi afetada pelo sistema de envelhecimento utilizado. Estes resultados evidenciam que as aguardentes envelhecidas com sistemas alternativos apresentam um perfil sensorial interessante; no entanto, é necessário a realização de mais trabalho de investigação de modo a validar a utilização destas tecnologias.

Palavras-chave: aguardentes vínicas envelhecidas, envelhecimento, perfil sensorial, vasilha de madeira, aduelas, dominós.

INTRODUCTION

The wine brandy is an alcoholic beverage produced from the distillation of wine. After the distillation, the freshly distilled brandy undergoes a period of maturation or ageing, which encompasses several changes. During the ageing time, the brandy must be kept into oak barrels, although interesting results are also verified with other kinds of wood, like chestnut (Canas et al., 1999; Belchior et al., 2001; Caldeira et al., 2006; Canas et al., 2011). During the wood ageing, the freshly distilled brandy undergoes important physical, chemical and sensory modifications. The kind of wood and the wood heat treatment seem to be the most determining factors for these sensory and physicochemical changes (Guymon and Crowell, 1970; Onishi et al., 1977; Artajona, 1991; Rabier and Moutounet, 1991; Puech et al., 1992; Viriot et al., 1993; Guichard et al., 1995; Canas et al., 1999; Belchior et al., 2001).

The ageing of brandies in wooden barrels, like with other beverages, has a great influence on their composition, affecting their sensory properties (Léauté et al., 1998; Caldeira et al., 2002, 2006, 2008).

The ageing of brandies requires a long period of time and consequently it is very costly. According to the European legislation (EC 110/2008) the wine brandies, as other alcoholic beverages, must be kept for several months (minimum of six months) in wooden oak barrels. At present, for cost-effective reasons, alternatives to the wooden barrel are being looked to simplify and accelerate the ageing process. One of these techniques consists of adding fragments of wood into the beverages. For this purpose, a great variety of wood fragments can be found in the market: chips, cubes, powder, shavings, granulates, blocks or segments, up to staves (Butticaz and Rawyler, 2007) and the effect of application of oak wood pieces has been studied in recent years for several alcoholic beverages, namely cider (Fan et al., 2006) and wine (del Alamo et al., 2004; Butticaz and Rawyler, 2007; Eiriz et al., 2007; Bautista-Ortin et al., 2008; Rodriguez-Bencomo et al., 2009). However, there is few data about the use of wood fragments in the ageing of brandy (Belchior et al., 2003; Canas et al., 2009a,b; Caldeira et al., 2010; Canas et al., 2013). The wood fragment size, the botanical and geographical origin of wood, the wood toasting level and the amount of applied wood seem to be important factors on the alternative ageing systems, which influence the quality of the final product (Fan et al., 2006; del Alamo et al., 2004; Eiriz et al., 2007; Butticaz and Rawyler, 2007; Bautista-Ortin et al., 2008; Rodriguez-Bencomo et al., 2009). Our first results on alternative ageing systems showed chemical discrimination (Canas et al., 2009a,b; Caldeira et al., 2010; Canas et al., 2013) between the brandies aged in wooden barrels and those aged with wood fragments (staves and tablets). The more discriminating variables were the amounts of some wood derived compounds in the brandies, namely furanic aldehydes (5-hydroximethylfurfural and furfural) and the volatile phenols (guaiacol, 4-methylguaiacol, syringol, 4-methylsiringol), which presented the highest levels in the brandies aged in wooden barrels and in those brandies aged in presence of tablets, respectively. Despite the chemical discrimination of the brandies the overall quality was not influenced by the alternative ageing system (Caldeira et al., 2010).

Thus, this work intends to evaluate the sensory modifications in the brandy aged in the presence of two types of wood fragments in comparison with a brandy aged in wooden barrels, over an ageing time of 30 months, using the same experimental design from our previous work (Caldeira et al., 2010).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Experimental design and sampling

The brandy ageing was studied in three ageing systems: 650 L new wooden barrels (B), 40-L stainless steel tanks with wood staves (S) and 40-L stainless steel tanks with wood tablets (T). The barrels and the stainless steels were filled with the same freshly distilled wine brandy (78.7%), from Lourinhã, Portugal. For each ageing system two different kinds of wood were evaluated, Portuguese chestnut wood (Castanea sativa Mill.) - CT and French oak wood (Quercus robur L.) from Limousin region – L. Two replicates of each essay modality were done and the brandies from the twelve experimental units were studied over the time.

The quantity of wood staves (two staves of 40 cm length×10 cm width×3 cm thickness and one stave of 17 cm length×10cm width×3 cm thickness) and tablets (47 tablets of 7 cm length×3 cm width×0.8 cm thickness) was calculated in order to obtain an equivalent surface area/volume ratio of the 650 L wooden barrel (57 cm2/L).

The barrels and the wood fragments were manufactured by the same cooperage (Tanoaria J.M. Gonçalves, Palaçoulo, Portugal) with a strong toasting degree. The barrels and staves toasting process was about 25 min over a fire of corresponding wood off-cuts, while the tablets were submitted to an oven toasting process.

The wooden barrels and the stainless steel tanks were placed in similar cellar conditions, at Adega Cooperativa de Lourinhã, Portugal.

The twelve brandies were sampled after 6, 12, 18, 24 and 30 months of ageing and their sensory profile and overall quality were evaluated by a tasting panel. The minimum of oak ageing time required in the European legislation for the wine brandies is six months but it is usual to find commercial aged brandies with more ageing time, so it is important to study the sensory modifications of the alternative systems during an extended period.

The experimental design is the same that has been used in previous works (Canas et al., 2009a,b; Caldeira et al. , 2010; Canas et al., 2013).

Tasting panel

The tasters were previously selected and trained (Caldeira et al., 1999). The reliability of each taster was evaluated by introducing blind sample replicates in all sessions, as described by Caldeira et al. (2002). The consistency, between repeated evaluations of the same brandy by a taster, was estimated using Pearsons correlation coefficient, which will be referred by reliability according to Brien et al. (1987). After this preliminary analysis, seven reliable subjects composed the average panel group.

Sensory attributes

The sensory attributes were previously generated by the tasting panel, according to Caldeira et al. (1999), which included colour, olfactory and gustatory attributes. The reliability of each attribute was evaluated as proposed by Caldeira et al. (2002), and only the reliable attributes were evaluated in this work.

Tasting conditions

All evaluations were carried out in a standardized tasting room with individual white boots, using standard wine-tasting glasses (ISO 3591, 2010) filled with 30 mL of diluted brandies. Fifteen days before the tasting session, the brandy samples were diluted with water, thereby reducing the ethanol concentration to 40 % v/v and they were stored in a dark room at 20º C until the tasting session.

At the tasting session, the samples were served at room temperature. The sensory evaluations were held in the mornings between 10:00 a.m. and 12:00 a.m. The panel evaluated the 12 brandies from each sampling time, which were randomly distributed by two sessions. Seven samples were presented in each session, in balanced orders to eliminate first-order carryover effects (Williams, 1949). Some replicates were introduced in all sessions in order to control the reliability of the panel.

All samples were spat out and water was provided for oral rinsing at the beginning of the experiments and also between brandy tasting.

The tasters were asked to scoring the thirty three sensory attributes (see Table II) with a structured scale (0-no perception to 5-highest perception). They also scored the overall quality of the brandies between 0 (without quality) and 20 (maximum quality).

Between each sampling time, training sessions were done monthly, in order to maintain the taster´s performance.

Statistical analysis

The sensory attributes intensities of the brandies were submitted to a three-way analysis of variance (factor 1 - wood, factor 2 – ageing system, factor 3 - ageing time; design with all interactions). For this analysis, and for each sensory attribute, it was used the average intensity of the seven reliable tasters. Calculations of the least significant difference (LSD) were applied for the comparison of different brandy attributes (Montgomery, 1991).

The results were also subjected to a multivariate analysis, namely principal component analysis and linear discriminant analysis.

The variance analysis and linear discriminant analysis of the data was performed using Statistica vs 98 edition (Statsoft Inc., USA). The principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out using NTSYS-pc package, version 2.1 (Exeter Software, USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

At each sampling time, several attributes of the brandies were evaluated by the tasting panel, namely five colour attributes (yellow-green, yellow-straw, golden, topaz, and greenish), sixteen olfactory attributes (alcohol, fruity, vanilla, woody, rancid, spicy, caramel, toasted, smoke, dried fruit, coffee, sweet, green, tails, glue, and rubber) and twelve gustatory attributes (sweetness, smooth, burning, astringency, roughness, bitterness, body, unctuous, flavour evolution, flavour complexity, retronasal aroma, and flavour persistence), as well as the overall quality. The dried fruits attribute was not reliable at first sampling evaluation and consequently the corresponding results were not included in the subsequent analysis. The panel was retrained and the reliability of this attribute was attained at the other tasting sessions.

Attributes and overall quality

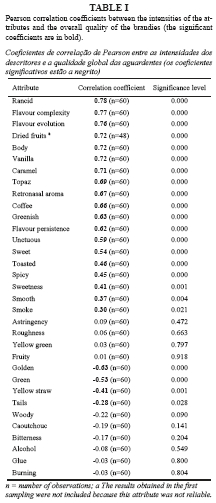

It was calculated the linear correlation between the attributes intensities, averaged across tasters and the overall quality (Table I).

The highest positive coefficients were found for two colour attributes (topaz, greenish), five olfactory attributes (rancid, dried fruits, vanilla, caramel and coffee) and six gustatory attributes (flavour complexity, evolution and persistence, retronasal aroma, body and unctuous). These attributes perception or intensity increase over the time (Caldeira et al., 2006), therefore it is expectable that they would be related with ageing process and could explain its positive influence in the overall quality of the aged wine brandy.

On the other hand, the attributes green, golden, yellow-straw and tails presented negative correlation with the overall quality. Golden and yellow-straw are colours well correlated with young brandies (Canas et al., 2000), while topaz is correlated with brandies with longer ageing, which could explain its relation with overall quality presented at Table I. Green is an important attribute of young wine brandies (Léauté et al., 1998) and its intensity decreased with ageing time in the wine brandies (Caldeira et al., 2006) and in whiskies (Reazin, 1983), which explains the negative correlation with overall quality (Table I), and are in accordance with our previous results for a brandy with longer ageing time (Caldeira et al., 2006). Tails are a negative aroma associated with the last phase of the distillation process, so it is predictable the negative correlation with overall quality that is presented in Table I. This result is also in accordance with that obtained in previous work (Caldeira et al., 2006).

Concerning the woody attribute the results obtained are quite different from those verified in our previous studies. In fact, it was found a negative correlation coefficient between the woody attribute, which varied between 1.0 and 2.7 (data not shown), and the overall quality (Table I), while a positive correlation was observed in other works (Caldeira et al., 2006), where the woody attribute ranged from 0.4 until 3.1. This could be probably related with the intensity range of the attribute, which is different in this experiment.

Influence of wood, ageing system and ageing time on sensory profile of brandies

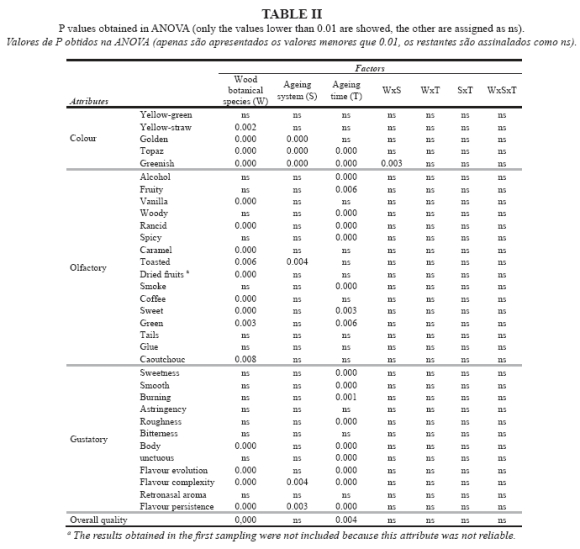

The all set of sensory results, obtained at the five samplings, were submitted to the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the results are presented at Table II. The results pointed out that the wood botanical species and the ageing time are the most discriminating factors concerning the sensory profile of the brandies. These outcomes are in agreement with our previous results (Caldeira et al., 2006; Caldeira et al., 2010).

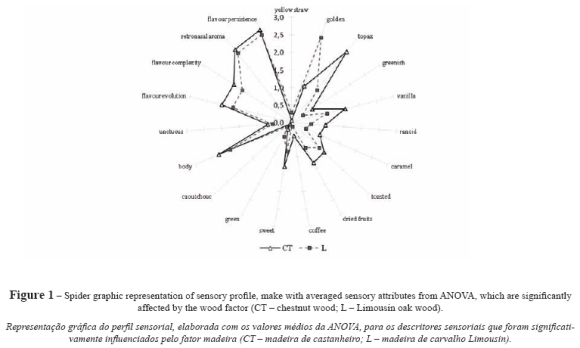

The chestnut aged brandies presented higher intensities of several attributes, like topaz, vanilla, rancid, caramel, toasted, dried fruits, coffee, sweet, body, flavour evolution and flavour persistence than the brandies aged with French Limousin oak (Figure 1). The intensity of the majority of these attributes increase over the time (Caldeira et al., 2006), so it means that the sensory profile of the chestnut aged brandies corresponds to an older brandy when compared with that of Limousin oak aged brandies. The vanilla attribute was positively correlated with the concentration of vanillin (Caldeira et al., 2008), tehrefore the highest intensities on vanilla attribute found in the brandies aged in chestnut wood (Table II and Figure 1) might be explained by the highest amount of vanillin of the brandies aged in chestnut wood (Canas et al., 2011; Canas et al., 2013). Regarding the toasted attribute, it is used to describe the odour of some volatile phenols and several unknown compounds and its intensity was related with the brandy content on volatile phenols and furanic aldehydes (Caldeira et al., 2008). Thus, the high intensity of toasted attribute presented in the brandies aged in chestnut wood (Table IIand Figure 1) could be explained by the highest concentration of furanic aldehydes found in the brandies aged in chestnut wood when in comparison with Limousin oak wood (Canas et al., 2011).

The brandies aged with Limousin oak presented higher intensities of the attributes yellow-straw, golden and green, which are more related to the youngest brandies (Canas et al., 2000, Caldeira et al., 2006).

These results reinforce the previous ones (Belchior et al., 2001; Caldeira et al., 2002; Caldeira et al., 2006; Canas et al., 2011) and pointing out once more the chestnut wood as an interesting alternative for the ageing of the wine brandies.

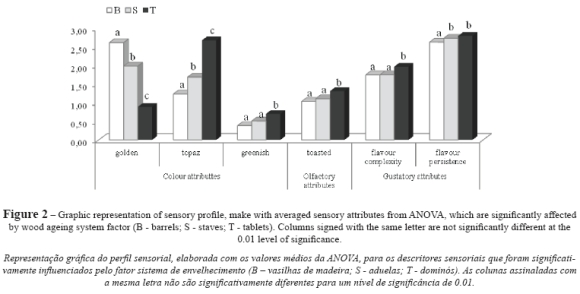

The ageing system affected significantly only six attributes, namely three colour attributes, one olfactory attribute and two gustatory attributes (Table II and Figure 2). The brandies aged with tablets presented lower intensities of the attributes golden and higher intensities of the attributes topaz, greenish, toasted, flavour complexity and flavour persistence than the brandies aged in wooden barrels. The brandies aged with staves presented an intermediate sensory profile. Taking into account the behaviour of these attributes over the time (Canas et al., 2000; Caldeira et al., 2006) it seems that the sensory profile of the brandies aged with tablets corresponds to an older brandy. The high intensities of toasted in the brandies aged with tablets can result from higher amounts of volatile phenols in these brandies (Caldeira et al., 2010), considering the positive correlation between these features (Caldeira et al., 2008).

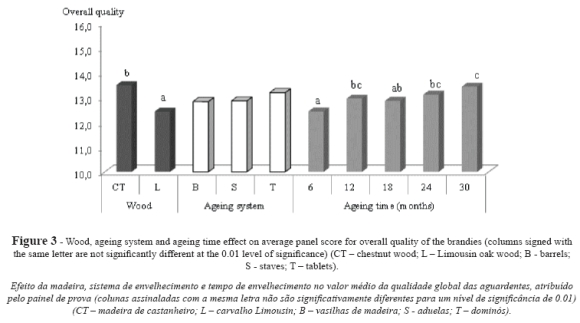

In accordance with slight sensory discrimination, the overall quality of the brandies it is not significantly affected by the ageing system. The overall quality was only significantly influenced by the wood botanical species and by the ageing time (Table II and Figure 3), which is in accordance with our previous results using the traditional ageing system in wooden barrels (Belchior et al., 2001; Caldeira et al., 2006).

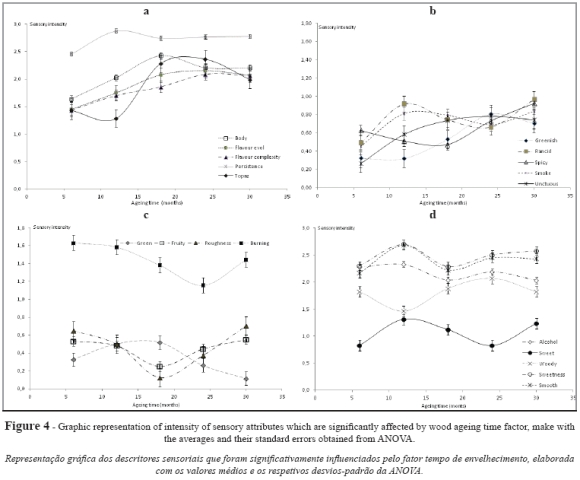

The ageing time influences significantly many sensory attributes (Table II). However, their evolution pattern is variable, as shown in Figure 4. The intensity of the majority of the attributes, such as topaz, greenish, rancid, spicy, smoke, unctuous, body, flavour, evolution and flavour persistence, increases over the time and tends to reach the equilibrium (Figure 4a,b). Similar results were found in a previous work, during an extended period of ageing, namely during five years (Caldeira et al., 2006). Taking into account the positive correlation of these attributes with overall quality (Table I), their increase can explain the raise of overall quality of the brandies over the time (Figure 3).

The green attribute presents a decrease over the time but that only starts after 18 months (Figure 4c). This result is in accordance with our previous work although the differences found in the ageing conditions and sampling time (Caldeira et al., 2006). The fruity, roughness and burning (Figure 4c) present a decrease, followed by a sharp increase during the ageing period of 30 months. These results are not in accordance with those of the mentioned work, in which it was detected a decrease of burning and fruity during five years of ageing.

Concerning the intensity of other five attributes, alcohol, sweet, woody, sweetness and smooth, they show an irregular pattern over the time (Figure 4d).

It was not detected a significant effect of the interaction between the factors (wood, ageing system and ageing time) on the intensity of the sensory attributes of the brandies, with exception to the greenish (Table II). It was detected a significant interaction between the wood and the ageing system in the greenish intensity. In fact, the effect of ageing system in the greenish intensity of the brandies was more pronounced when the chestnut wood was used in comparison with Limousin oak wood (data not shown).

Multivariate analysis

Multivariate analysis was also applied to check whether the measured variables could help to distinguish among pre-established groups (wood botanical species, ageing system and ageing time).

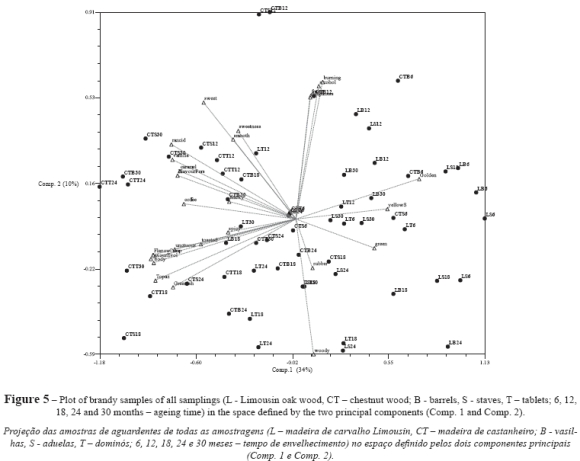

The average intensities of the brandys attributes were submitted to the principal component analysis (PCA). It was analysed a matrix composed by 60 objects (12 brandies x 5 sampling times) and 26 variables (only the attributes with significant effects shown in the Table II were considered).

In the PCA analysis (Figure 5) the first two components are those which contribute for major variability of the results (34 and 10%, respectively). The brandy samples are distributed across the space created by the two main components (Figure 5). Two group of attributes presented higher contribution to the first component with loadings in opposite sides. The first group is composed by yellow-straw, golden and green and the second group is constituted by topaz, greenish, rancid, vanilla, body, flavour complexity, flavour evolution and flavour persistence. The attributes of the first group are more related with young brandies, namely the yellow-straw and green (Canas et al., 2000, Caldeira et al., 2006). The attributes which influence the opposite side of the component 1 are more related with older brandies (Canas et al., 2000, Caldeira et al., 2006) since their intensity increase over the time, like topaz, vanilla, toasted, body, flavour complexity, evolution and persistence. Thus the component 1 seems to split the samples based on its degree of maturation. Indeed, the young brandies are located in the positive side of the component while the older brandies are located in the opposite side. The brandies aged with the chestnut wood show a tendency to be located in the side more related with the attributes of matured brandies while the brandies aged with Limousin oak tend to be located in the opposite side. Concerning the ageing system, it seems that it is not possible to separate the samples according to this factor, which is in agreement with ANOVA results.

It was also performed a linear discriminant analysis with all set of the results, considering the ageing system as discriminant factor, but it was not found any significant discriminant factor, as expected based on the ANOVA results.

Therefore, it seems that sensory data do not permit an easy discrimination of the brandies based on the ageing system used. On the contrary, the chemical analysis of the corresponding brandies allow the discrimination of the brandies based on the ageing system (Canas et al., 2009a,b; Caldeira et al., 2010; Canas et al., 2013). Therefore, the alternative ageing systems allow obtaining aged brandies with similar quality to the brandies aged in the traditional system in wooden barrels, and it is possible to found chemical markers in order to control these technologies.

CONCLUSIONS

The results presented in this work suggest that the use of alternative systems allow producing brandies with slightly different sensory profile. Actually, the brandies aged with alternative systems presented an overall quality similar to those aged in wooden barrels, and the use of tablets or staves in the brandy ageing seems to be an interesting alternative.

These results, obtained with chestnut and oak wood during an ageing time of 30 months, reinforce that chestnut wood is suitable for the ageing of the wine brandies.

Despite these outcomes, further research is needed in order to validate the use of these alternative technologies in the brandy ageing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the participation of tasting panel (Francisco Carlos, João Melícias, Manuel Bento, Maria Lucinda Abrantes, Rui Pereira, Sofia Catarino), and the financial support of INIAV-Dois Portos and Adega Cooperativa da Lourinhã.

REFERENCES

Artajona J., 1991. Caracterisation del roble según su origen y grado de tostado, mediante la utilizacion de GC y HPLC. Viticultura/Enologia Profesional, 14, 61-72. [ Links ]

Bautista-Ortin A.B., Lencina A.G., Cano-Lopez M., Pardo-Minguez F., Lopez-Roca J.M., Gomez-Plaza E., 2008. The use of oak chips during the ageing of a red wine in stainless steel tanks or used barrels: effect of the contact time and size of the oak chips on aroma compounds. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res., 14, 63-70. [ Links ]

Belchior A.P., Almeida T.G.T., Mateus A.M., Canas S., 2003. Ensaio laboratorial sobre a cinética de extracção de compostos de baixa massa molecular da madeira pela aguardente. Ciência Téc. Vitiv., 18, 29-41. [ Links ]

Belchior A.P., Caldeira I., Costa S., Lopes C., Tralhão G., Ferrão A.F.M., Mateus A.M., Carvalho E., 2001. Evolução das características físico-químicas e organolépticas de aguardentes Lourinhã ao longo de cinco anos de envelhecimento em madeiras de carvalho e castanheiro. Ciência Téc. Vitiv., 16, 81-94. [ Links ]

Brien C.J., May P., Mayo O., 1987. Analysis of judge performance in wine quality evaluations. J. Food. Sc., 52, 1273-1279. [ Links ]

Butticaz S., Rawyler A., 2007. Différenciation analytique des vins élevés en fût de chêne et macérés avec des copeaux de chêne. Rev. S. Vitic. Arboric. Hortic., 39, 367-373. [ Links ]

Caldeira I., Anjos O., Portal V., Belchior A.P., Canas S., 2010. Sensory and chemical modifications of wine-brandy aged with chestnut and oak wood fragments in comparison to wooden barrels. Anal. Chim. Acta, 660, 43-52. [ Links ]

Caldeira I., Belchior A.P., Clímaco M.C., Bruno de Sousa R., 2002. Aroma profile of Portuguese brandies aged in chestnut and oak woods. Anal. Chim. Acta, 458, 55-62. [ Links ]

Caldeira I., Bruno de Sousa R., Belchior A.P., Clímaco M.C., 2008. A sensory and chemical approach to the aroma of wooden aged Lourinhã wine brandy. Ciência Téc. Vitiv., 23, 97-110. [ Links ]

Caldeira I., Canas S., Costa S., Carvalho E., Belchior A. P., 1999. Formação de uma câmara de prova organoléptica de aguardentes velhas e selecção de descritores sensoriais. Ciência Téc. Vitiv., 14, 21-30. [ Links ]

Caldeira I., Mateus A.M., Belchior A.P., 2006. Flavour and odour profile modifications during the first five years of Lourinhã brandy maturation on different wooden barrels. Anal. Chim. Acta, 563, 264-273. [ Links ]

Canas S., Belchior A.P., Caldeira I., Spranger M.I., Bruno de Sousa R., 2000. A cor e sua evolução em aguardentes Lourinhã nos três primeiros anos de envelhecimento. Ciência Téc. Vitiv., 15, 1-14. [ Links ]

Canas S., Caldeira I., Belchior A.P., 2009a. Comparação de sistemas alternativos para o envelhecimento de aguardente vínica. Efeito da oxigenação e da forma da madeira. Ciência Téc. Vitiv., 24, 33-40. [ Links ]

Canas S., Caldeira I., Belchior A.P., 2009b. Comparison of alternative systems for the ageing of wine brandy. Wood shape and wood botanical species effect. Ciência Téc. Vitiv., 24, 90-99. [ Links ]

Canas S., Caldeira I., Belchior A.P., 2013. Extraction/oxidation kinetics of low molecular weight compounds in wine brandy produced in alternative ageing systems. Food Chem., 138, 2460-2467. [ Links ]

Canas S., Caldeira I., Belchior A.P., Spranger M.I., Clímaco M.C., Bruno-de-Sousa R., 2011. Chestnut wood: a sustainable alternative for the aging of wine brandies. In: Food quality: control, analysis and consumer concerns. 181-228. Medina D.A., Laine A.M. (eds.), Science Publishers Inc., New York. [ Links ]

Canas S., Leandro M.C., Spranger M.I., Belchior A.P., 1999. Low molecular weight organic compounds of chestnut wood (Castanea sativa L.) and corresponding aged brandies. J. Agric. Food Chem., 47, 5023-5030. [ Links ]

del Alamo M., Nevares I., Carcel L.M., Navas L., 2004. Analysis for low molecular weight phenolic compounds in a red wine aged in oak chips. Anal. Chim. Acta, 513, 229-237. [ Links ]

Eiriz N., Santos-Oliveira J.F., Clímaco M.C., 2007. Fragmentos de madeira de carvalho no estágio de vinhos tintos. Ciência Téc. Vitiv., 22, 63-71. [ Links ]

Fan W., Xu Y., Yu A., 2006. Influence of oak chips geographical origin, toast level, dosage and aging time on volatile compounds of apple cider. J. Inst. Brew., 112, 255-263. [ Links ]

Guichard E., Fournier N., Masson G., Puech J.-L., 1995. Stereoisomers of β-methyl-γ-octalactone. I-Quantification in brandies as a function of wood origin and treatment of the barrels. Am. J. Enol. Vitic., 46, 419-423. [ Links ]

Guymon J.F., Crowell E.A., 1970. Brandy aging. Some comparisons of American and French oak cooperage. Wines & Vines, 1, 23-25. [ Links ]

ISO 3591, 2010 - Sensory analysis - Apparatus - Wine-tasting glass. International Organization for Standardization, Genève. [ Links ]

Léauté R., Mosedale J.R., Mourgues J., Puech J.-L., 1998. Barrique et vieillissement des eaux-de-vie. In: Oenologie fondements scientifiques et technologiques. 1110-1142. Flanzy C. (ed.), Collection Sciences et Techniques Agroalimentaires, Lavoisier Tec&Doc, Paris. [ Links ]

Montgomery D.C., 1991. Design and analysis of experiments. Third Edition, 668p. John Wiley & Sons, Singapore. [ Links ]

Onishi M., Guymon J.F., Crowell E.A., 1977. Changes in some volatile constituents of brandy during aging. Am. J. Enol. Vitic., 28, 152-158. [ Links ]

Puech J.-L., Lepoutre J.P., Baumes R., Bayonove C., Moutounet M., 1992. Influence du thermotraitement des barriques sur l´évolution de quelques composants issus du bois de chêne dans les eaux-de-vie. In: Elaboration et connaissance des spiritueux. 583-588. Cantagrel R. (ed.), Lavoisier Tec&Doc, Paris. [ Links ]

Rabier Ph., Moutounet M., 1991. Évolution d`extractibles de bois de chêne dans une eau-de-vie de vin. Incidence du thermotraitement des barriques. In: Les eaux de vie traditionnelles d`origine viticole. 220-230. Bertrand A. (Ed.), Lavoisier Tec&Doc, Paris. [ Links ]

Reazin G.H., 1983. Chemical analysis of whisky maturation. In: Flavour of distilled beverages. Origin and development. 225-240. Piggott J.R. (ed.), Ellis Horwood Limited, West Sussex, England. [ Links ]

Rodriguez-Bencomo J.J., Ortega-Heras M., Perez-Magariño S., Gonzalez-Huerta C., 2009. Volatile compounds of red wines macerated with Spanish, American and French oak chips. J. Agric. Food Chem., 57, 6383-6391. [ Links ]

Viriot C., Scalbert A., Lapierre C., Moutounet M., 1993. Ellagitannins and lignins in aging of spirits in oak barrels. J. Agric. Food Chem., 41, 1872-1879. [ Links ]

Williams E.J., 1949. Experimental designs balanced for the estimation of residual effects of treatments. Aust. J. Sci. Res. A2, 149-168. [ Links ]

*Corresponding author:

Tel.:+351261712106, Fax:+351261712426, e-mail: ilda.caldeira@iniav.pt

(Manuscrito recebido em 06.05.2013. Aceite para publicação em 14.08.2013)