Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.235 Lisboa jun. 2020

https://doi.org/10.31447/AS00032573.2020235.01

ARTIGOS

Comparing local transitions in Southern Europe: center-periphery relations and governors in the South of Spain and Portugal, 1970-1980.

Comparando as transições locais no Sul da Europa: relações centro-periferia e os governadores civis do Sul de Espanha e Portugal, 1970-1980.

Maria Antónia Pires de Almeida1

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5583-3099

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5583-3099

Julio Ponce Alberca2

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9715-7113

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9715-7113

1CIES - Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL). Sala 2W10, Edifício Sedas Nunes, Av. das Forças Armadas - 1649-026 Lisboa, Portugal. mafpa@iscte-iul.pt

2Departamento de Historia Contemporánea, Universidad de Sevilla. Doña María de Padilla, s/n - 41004 Sevilha, Espanha. jponce@us.es

ABSTRACT

This article focuses on a comparative history of civil governors in Spain and Portugal, particularly on the role played by governors in the transitional processes in the South of each country. Two databases of governors have been made available, one for Portugal and another for Spain. Our research pays special attention to governors’ political profiles and their relations with the central government and local powers. Eight Spanish provinces (Almería, Cádiz, Córdoba, Granada, Huelva, Jaén, Málaga and Sevilla) and five Portuguese districts (Beja, Évora, Faro, Portalegre and Setúbal) were analysed. Our conclusions emphasise the need to consider the local dimension to better understand democratisation processes.

Keywords: Southern Europe; transition processes; governors; local administration; centre-periphery relations.

RESUMO

Este artigo incide sobre a história comparativa dos governadores civis em Espanha e Portugal, especialmente no papel que desempenharam nos processos de transição no sul de cada país. Duas bases de dados foram disponibilizadas, uma para Portugal e outra para Espanha. A nossa investigação dá especial atenção aos perfis políticos dos governadores civis e às suas relações com o governo central e com os poderes locais. Foram analisados oito províncias espanholas (Almería, Cádiz, Córdoba, Granada, Huelva, Jaén, Málaga e Sevilla) e cinco distritos portugueses (Beja, Évora, Faro, Portalegre e Setúbal). As nossas conclusões enfatizam a necessidade de considerar a dimensão local para melhor compreender os processos de democratização.

Palavras-chave: Europa do sul; Processos de transição; governadores civis; administração local; relações centro-periferia.

Introduction

Comparative studies of political transition processes are well developed in the Social Sciences, especially in Political Science, in which so-called transitology studies are almost a classic. Despite a certain delay, throughout the last 15 years historians too have been responsible for a substantial rise in the number of studies devoted to these processes. Nevertheless, comparative historical studies remain relatively scarce, but to date, monographs and an array of articles on the political transition processes of both Spain and Portugal are available (Muñoz, 1997; Medina, 1995; Bernecker, 1990; Cervelló, 1995; Dulphy & Yvés, 200; Diamandouros & Gunther, 2001; Lemus, Rosas & Varela, 2010). Likewise, a number of comparative analyses of the dictatorships in Southern Europe have been published (Fernández, 2011; González, 2015). There are also other examples of comparative studies, in this case with South America (Sánchez, 2003; Ortiz & Yunuen, 2000).

These processes of transformation have been revisited as time has passed. The initial optimism derived from the successful culmination of political change gradually gave way to more nuanced accounts once these Southern democracies were firmly established inside the European Union (EU). Even critical analyses of transition processes have arisen, particularly in Spain, in the context of a revision of the country’s recent past, which has focused above all on the Civil War and Francoist dictatorship, including the succession to the office of Head of State for which the groundwork was laid in 1969.

The historical study of transition processes has been conducted through a multitude of lenses. Regime change, ideological transformation, and the new political relations determined by the restoration of political freedoms have all attracted attention from researchers. Other fields of great potential remain largely unexplored, however. Among these is the role of the state (Dyson, 1980), whose structures experienced a much slower transformation, with certain traits remaining unaltered for years (aside from its role as a domination structure, as analyzed - Raphael, 2008 - for the 19th Century). A case in point is the continuity of the Administrative Procedures Law in the case of Spain (1992), making no mention of the persistence of certain administrative cultures, a field scarcely explored in Spain and Portugal that could be of the utmost interest (Jamil-Askvik-Hossain, 2013M; Shama, 2002). In this regard, we believe it is worthwhile to clarify the differences between the concepts of “regime” and “state” in order to better understand instances of political transformation in which the former is profoundly altered while the second remains untouched (Fishman, 1990; Linz & Stepan, 1996).

The transformation of the state is often conflated with the establishment of new institutions under a system of constitutional guarantees. But the state is much more than that, and such a limited view fails to account for administrative structures, bureaucracy, and public policy, among other elements (Raphael, 2008). Indeed, it is necessary to highlight that the fundamental structures of the state remained unaltered in the Spanish case throughout the early years of the Transition and at least until the establishment of Autonomous Regions. Obviously, the implementation of Title VIII of the Spanish Constitution modified the territorial organization of the state and thus its structure. Yet even so, the true reach of the emergence of Autonomous Regions, in terms of the treatment received by local administrations as well as the extent to which the administrative culture may have suffered a radical transformation, is not altogether clear.

We can likewise place the Portuguese case under scrutiny, despite the sudden nature of the advent of democracy through the revolution of 25 April 1974. Indeed the pace of political change was rapid throughout the first 19 months (the so-called Processo Revolucionário em Curso or PREC), until the situation stabilized in 1976 with the approval of the Constitution (April) and the first legislative (April), presidential (June) and local (December) elections. However, the general structure of the Portuguese state would experience a much slower transformation, as would the country’s administrative cultures and the general shape of its administrative codes. In fact, the 1940 Administrative Code remains in force to this day, although parts of it were repealed by the 1976 Constitution and later legislation. Further, even though those who had held key offices in the Estado Novo were deprived of the right to vote and stand for election (Decreto-Lei 621-A/74, of 15 November 1974), most of the state’s civil servants retained their posts.

The greater resistance to change exhibited by administrative structures, as compared to political ones, by no means implies that the former were never modified. However, their transformation was neither complete nor immediate. To the extent that Autonomous Regions were developed in Spain and that greater autonomy was granted to Portuguese local administrations, governors gradually lost their raison d’ être in both countries. In Spain, the office was eliminated in 1997 (giving way, however, to Government delegations and sub-delegations in each province); in Portugal, governors disappeared in 2011, their powers taken over by other administrative bodies[1]

In view of the above, the analytical lens we propose is the study of the state from “below”, that is to say from the local dimension (with the concept of “local” encompassing the periphery in a broad sense, including provinces and sub-state entities) (Goldsmith, 1996; Loughlin-Hendriks-Lidsröm, 1997; and Page, 1991). This dimension has been partially studied from a social perspective (Fernandes, 2014, 2017; Herrera, 2007; Ortíz Heras, 2016), but the angle of analysis we propose here involves studying how the Portuguese and Spanish transitions were implemented in each country’s provinces and districts and how change was experienced in local councils, concelhos and freguesias. Obviously, this approach implies methodological problems given the wide range of local and provincial institutions (in the case of Spain, the numerous ayuntamientos aside from one diputación in each province; similar to the Portuguese concelhos and distritos). To this end, we consider that the most appropriate research strategy is to analyze civil government institutions in each country using the databases published by the authors and made available to the academic community (see http://grupo.us.es/estadoypoder/index.php?page=Base-de-datos-de-Gobernadores-Civiles). In both cases, local and provincial bodies were intensely dominated by the governador or gobernador civil, who was appointed by the central government and acted as its representative in each province or district. In the following pages we shed light on who these governors were in the South of each country and examine how they acted following guidelines established by the central government. In other words, we hope to provide answers to at least two broad questions: (1) who these governors were and how they fulfilled their role, (2) to what extent the local transition processes in the two countries were similar in these Southern provinces/districts.

Governors in southern Spain: the eight andalusian provinces

One basic tenet of the Spanish transition was its incremental nature. If this feature was salient in initiatives originating in the central government, it was even more visible in local administrations, which had remained in the hands of the same authorities carried over from the Francoist regime. The political leadership of local institutions (city and provincial councils) did not change upon Franco’s death, with the exception of a few which had to be replaced by interim managing committees. This rather anomalous situation persisted until April 1979. Cabinet members and civil governors were by and large newly appointed to such offices (though many had previously collaborated with the dictatorship in other roles) and as such responded to the guidelines laid out for the country’s political transformation, whereas mayors and provincial council presidents remained virtually unchanged. If there were no serious confrontations between the “new” central and the “old” local politicians this was only due to the inertia left behind by the Francoist regime. Local politicians were considered, above all, administrators of public affairs, and were thus quite accustomed to following guidelines from civil governors in the framework of a hierarchical political-administrative pyramid structure (Ponce, 2014c).

It is true that by 1975 governors had lost part of the extraordinary power they had enjoyed in the past (for example, during the 1940s), but their powers were still broad and, more importantly, popular perception of the office remained imbued with the respect and veneration inspired at the time by the central government’s representative in local spheres (Ponce, 2012, 2014a, 2014b). The governor’s guidelines were generally followed without argument. Further, governors controlled the mechanisms for law and order as well as official propaganda and exercised oversight of local administrations. The central government was well aware of their power and did not hesitate to use it in favor of a gradual restoration of political freedoms and the advance of the democratization process. In that context, local institutions (ayuntamientos and diputaciones) would not jeopardize government-initiated reforms.

The selection of governors was a delicate matter involving an array of criteria, among which the government’s trust and the candidate’s suitability for the post were paramount. During the Francoist dictatorship, a governor’s appointment required the acquiescence of both the Home Office (Ministerio de la Gobernación) and the Secretariat General of the Movimiento, as governors were the highest representatives in each province for both state and party (though the latter lost pre-eminence as time went by). In the changing 1960s, governors became even more significant as economic crisis, popular unrest, attempts at reform, and uncertainty regarding the future increased the difficulty of political coordination at the local level, a task that was complex and diverse to begin with. Hence the relatively long permanence of civil governors, which had been a hallmark of the ‘50s and ‘60s, gave way to more frequent renovation in the ‘70s. Indeed, president Carlos Arias Navarro (1974-1976) and president Adolfo Suárez (July 1976 on) - both of whom, incidentally, had been civil governors in the past - often renovated their civil governors, whether by rotating existing ones among different provinces or by incorporating new appointees (Ponce, 2018).

Certainly, president Arias Navarro never went beyond timid attempts at reform that proved clearly insufficient. But with the appointment of Adolfo Suárez, the situation changed considerably. A profound political reform was proposed that required the cooperation of civil governments. Thus, in late August a meeting of civil governors was held in Madrid, called by Suárez’s new cabinet and his Home Secretary Rodolfo Martín Villa. The profiles of the attendees reflects the increasing frequency of appointments - around 60 per cent had been appointed by Arias Navarro cabinets (after 1974), with up to 40 per cent having been appointed in the brief two months that Suárez had been in power. The main aim of the meeting was to ensure the preservation of law and order and the adequate celebration of the referendum that was to take place in the following months in order to pass the Law for Political Reform.

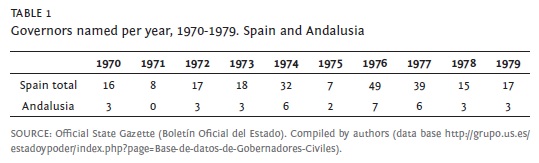

The number of governors appointed in the Andalusian provinces, in relation to the national total, is shown in Table I.

As seen, in Spain as a whole 218 governors were appointed between January 1970 and December 1979. Of these, 36 appointments (16.5 per cent) were to the Andalusian provinces. This percentage for Andalusia corresponds roughly to the percentage of Spain’s total provinces accounted for by Andalusia (16 per cent). In Spain, as in the region, appointments became slightly more frequent starting in 1975, with 45 per cent of the decade’s appointments taking place before the end of that year and a full 55 per cent over the subsequent three and a half years, and especially in 1976-1977. This was a result of the numerous appointments made by the Adolfo Suárez government, as governors were tasked with much of the responsibility for maintaining law and order in the provinces while the political transformation process gained traction.

Among the 36 appointments to governor in Andalusian provinces between 1970 and 1979 (as shown in Table 2), 3 names appear on more than one occasion: Manuel Hernández Sánchez (Cordoba 1970-1973 and Malaga 1973-1974), Rafael Hurtado (Huelva 1977-1978 and Malaga 1978-1979), and Alberto Leyva Rey (Granada 1970-1974 and Seville 1974-1976). This leaves the total number of governors appointed to Andalusia at 33. On average, a governor in that decade remained in office for little over two years, with a notable increase in instability after 1975 (2.2 years on average until 1975; 1.9 after that year).

A large share of those 33 men had gained experience in similar posts before or after being appointed to an Andalusian province: though 15 governors held such a position only once, 11 of them were civil governors on two occasions and 5 on three occasions, in addition to the exceptional cases of Hellín Sol (appointed governor four times) and Nicolás García (five appointments). The average age of a governor upon his appointment to Andalusia was 46, with Eugenio Herrera Martín (63 when he was sent to Cordoba) and José Manuel Menéndez-Manjón (34 when he arrived in Granada), among others, at each end of the age spectrum. Most had been born between 1920 and 1939 and were thus part of the so-called generation of silence, which had played no active role in the Civil War but was very present in the last few years of the dictatorship and the early years of the transition to democracy. A comparison between the average age of appointees before and after 1975 yields a small decrease (47 years old in the earlier period versus 45.7 in the later one) - governors appointed after Franco’s death were generally younger. But the age profile was not very different from that of the early 1960s, when the incorporation of younger governors who had not participated in the war first started and 20 out of 50 governors were under 45 years of age (Herrero Tejedor, 1962).

A true generational renewal among civil governors would not come until 1982, when the first Socialist (PSOE) government appointed a great deal of new governors averaging 35 years of age[2], clearly younger than what had previously been the norm for such posts.

By place of origin, we know that most governors appointed to Andalusian provinces were not natives of the region (up to 75 per cent according to our data). This reluctance to appoint governors to their own provinces was common and aimed at minimizing their susceptibility to local pressure and influences. Yet this did not preclude the governor from identifying with “his” province or being sensible to its demands. In fact the government occasionally selected people from the region or familiar with it. There were indeed 8 Andalusian governors appointed to provinces in the region throughout the 1970s due to specific local circumstances that had to be taken into account when appointing a governor to a province. An extreme case was José González de la Puerta, appointed governor of his native Malaga in 1975 as the right-hand man of the then Minister-Secretary of the Movimiento, the likewise Malaga-born José Utrera Molina.

In terms of education, most governors had studied Law and were employed in this field (lawyers, judges, public prosecutors, members of the State Administration, Vertical Syndicate attorneys). Around 60 per cent of governors were in this group, followed by military men (almost 10 per cent) and an array of degrees (journalists, doctors, agricultural engineers, economists, etc.). It is worth noting that until 1975 governors who had studied Law accounted for a vast majority; it was only after 1976 that there was a rise in governors educated in other fields, though experience in Law retained its weight. Governors originating in the armed forces disappeared after 1977, when a royal-decree act made the two incompatible. Yet there was no need to implement this change in the Andalusian provinces, as the region’s governors were all civilians at that point, unlike in Portugal, where military men played a key role.[3]

Obviously, governors’ political allegiance was linked to the Movimiento, especially to the Francoist Vertical Syndicate, which was only natural given the fact that governors were also provincial heads of the Movimiento until 1977. Hence, we have Víctor Arroyo, Manuel Hernández, Enrique Gómez (syndicate delegates), and the syndicate attorneys José María Bancés and Mariano Nicolás. But it must be added that although Movimiento membership was a common denominator among most governors, not all of them understood and interpreted their membership in the same way. There were deeply Francoist governors, such as the Lerida-born Joaquín Gías Jové (National Counselor of the Movimiento and member of Cortes), who opposed the Law for Political Reform, while others experienced an evolution from the single party to Adolfo Suárez’s Democratic Centre Union (Unión del Centro Democrático or UCD). A clear instance of the latter was Mariano Nicolás García, five times governor between 1963 and 1977 and later appointed Director General of Security by Home Secretary Rodolfo Martín Villa (see the above-mentioned database and Ponce 2012, 2014c, 2018).

The flexibility exhibited by most governors in their identification with and interpretation of the single party reflected the moderation and tact required to perform their duties. Excessive radicalism of any kind would not have suited their role as representatives of the central government in the provinces. It was precisely those governors who showed the greatest adaptability who were appointed to subsequent posts as civil governors in other provinces. Further, some were promoted to posts in Madrid (generally as Directors General). Indeed, being a member of the Movimiento did not preclude later joining the UCD and pursuing a political career. Selection criteria were based more on tact and moderation, as well as the necessary loyalty to the government and a commitment to political change. To them, it was evident that Francoism would not survive with Franco gone, regardless of any past allegiance to the Movimiento.

A cursory glance at the offices held by governors before and after a posting at a civil government reveals the importance of being able to adapt to the circumstances if one wanted to pursue a political career. Despite having been appointed by very different cabinets, governors before and after 1975 present similar profiles in terms of the start of their career in politics. Most had been provincial delegates for one Ministry or another, syndicate delegates, members of the Spanish University Syndicate (SEU), local authorities (mayors, provincial council presidents), and civil servants in a variety of ranks. Those who understood how times were changing were able to adapt and become the appropriate governors to launch the political reform process in the provinces or even cooperate with the central government in Madrid. As one would expect, most among the latter group had been appointed after 1975 (José María Fernández, José María Bancés, Enrique Gómez, and José Estévez), but there were also governors appointed before Franco’s death, such as Manuel Ortiz, who would reach the post of undersecretary with President Suárez (Sánchez, 2006).

We shall now examine their Portuguese counterparts in order to analyze similarities and differences between the two countries.

Portuguese governors of Beja, Évora, Faro, Setúbal, and Portalegre

We have solid data on Portuguese governors in the 1970s as well as much larger thematic, spatial, and chronological framework, with the biographies of 3,102 chamber presidents and 402 civil governors in the 18 districts of continental Portugal plus another 4 districts corresponding to the islands (Madeira and Azores) since 1936 (Almeida, 2013, 2014, 2017).

Just as they had been in Spain (since 1849), Portuguese governors were an essential tool in the construction of the liberal state from the moment the post was created (1835). Included among their broad powers were the organization of elections and the transmission of legislation and orders from above to subordinate local authorities. This model was passed on to the Republic of 1910 and consolidated after the coup of 1926. As the highest representatives of the central government, they served as an instrument for the establishment of the Estado Novo across the length and breadth of Portugal. In this regard, it is worth highlighting how old elites were incorporated into the local authorities of the dictatorship, just as the Republic had previously recruited monarchic local elites. Such phenomena help to understand the significance of civil governors in the Portuguese transition process. Above all, it is interesting to know who these governors were and how their political action compared to that of their Spanish counterparts.

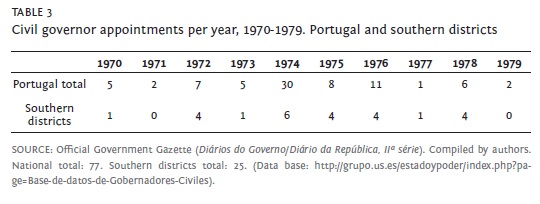

The first thing to highlight is their number. In the five Portuguese districts under study (Setúbal, Portalegre, Évora, Beja, and Faro) there were a total of 25 appointments between 1970 and 1979. This gives us an average of 5 appointments per district (as opposed to 4.5 in Spain), with a smaller deviation from the average in these Portuguese districts than in the Andalusian provinces (where Huelva had 7 appointments and Cadiz only 2). A comparison between governors appointed in Portugal as a whole and those appointed in the districts analyzed can be seen in Table 3:

Two features of the data above stand out. In the first place, the revolution of April 1974 led to the replacement of governors in every district in Portugal. Further, there were several districts where governors changed twice during 1974 (though not always due to the effects of the revolution: in the case of Setúbal, there were 2 appointments that year because the last cabinet of the dictatorship had named Serafim de Jesus Silveira in February). In any case, permanence in the post had become more volatile due to the massive wave of initial replacements as well as the instability derived from difficulties in consolidating political change. The five districts studied accounted for roughly 25 per cent of Portuguese districts, but the number of appointments was well above that percentage between 1975 and 1978. This means that the Southern districts were above the national average in terms of the number of appointments per year. Only one of these years offered a different snapshot: in 1974, there were proportionally fewer appointments in the South.

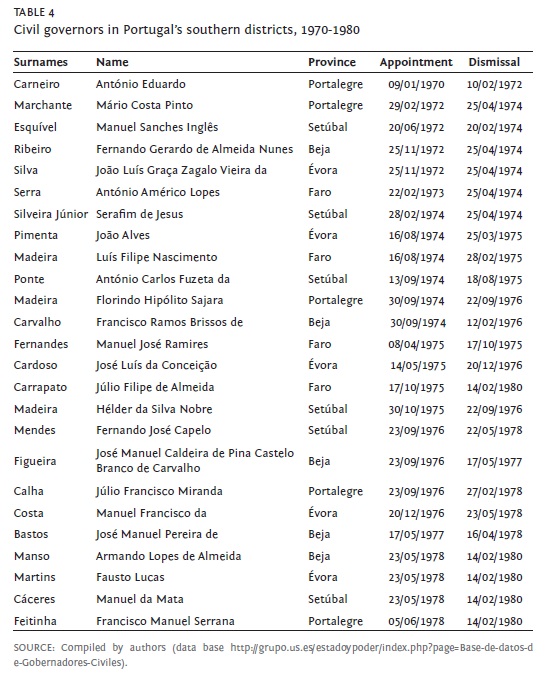

Who were these governors? Between 1970 and 1980 there were 25 appointments. To this we must add the 4 governors who had been in their post since the early 1960s, yielding a total of 29 governors. Significantly, there was no rotation among these postings (that is, no governors were moved to different provinces in the South) between 1974 and 1980. This was a departure from what had been common practice during the Portuguese dictatorship. Before the revolution, many governors ended up being appointed to a different district, creating a closed “corps” of sorts with relatively few new appointees. Out of the total 29 governors, we know that 11 were already governors during the dictatorship, while 18 became so after 14 April. Table 4 lists the civil governors under study:

We know the ages of 18 of the 29 governors, who averaged 45.9 years old when appointed. But it is remarkable that the average age was higher (53.3) in the later years of the Estado Novo than it was after 25 April (42.2). This was the outcome of the Salazar regime’s aging political personnel as well as of the relative youth of the new authorities, who would then go on to age as well: the average age of Portuguese governors between 1974 and 2011 was 48.5 years old. As we have seen, a similar trend transpired in Spain, albeit nuanced: late Francoist governors were not that old, nor those appointed by Suárez that young.

In terms of their place of birth, it is worth noting that up to 42.9 per cent of these governors had been born in the same district to which they were appointed, while 57.1 per cent had a different place of origin. This suggests that their district of origin was not a significant factor in determining who was to be appointed to any given district. In Spain, by contrast, it was fairly common to avoid appointing governors to their own province of birth. This was an attempt to reinforce a governor’s autonomy from the possible influence of local networks -a goal that, nonetheless, sometimes proved elusive. Was this difference due to a higher degree of “localism” among Portuguese governors with regard to Spanish ones? Were Portuguese governors better attuned to their respective districts?

We can offer no conclusive answers to these questions in this paper, but one fact may shed some light on the issue: Portuguese governors slightly outlasted their Spanish counterparts in their postings, at least in the South of each country toward the end of their respective dictatorships (2.3 versus 2.2 years on average). Yet in the early years of each country’s democratic regime the situation was reversed: 1.5 versus 1.9 years for Portugal and Spain respectively. This seems to align well with each country’s general landscape: under dictatorship, Portuguese governors generally remained longer in office, with an average of 4.3 years between 1936 and 1974 against the Spanish average of 2.8 years (counting those appointed between 18 July 1936 and 20 November 1975). As noted, Portuguese governors were often appointed to their own districts of origin (this was not the case in Spain) and this trend seems to suggest more intense relations between the Civil Government and local spheres. This may well have favored stability and governors’ permanence in their postings. As a consequence, it is possible to state - pending further research on the matter - that Portuguese governors were more “localized” with regard to local interests than Spanish ones. However, this trend was reversed starting in the early 1970s and at least until 1980 (and probably thereafter). Portuguese governors became more volatile, as opposed to local authorities such as mayors, who managed to string together term after term (the so-called dinosaurs), to the point that the number of terms for this office has had to be capped to a total of three (Law 46/2005 of 29 August 2005, first applied in the autarchic elections of 2013). This was not the case in Spain, where mayors lasted less time and governors could easily remain in their postings for longer periods, even as they gradually lost powers throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

In terms of education, most Portuguese governors in the 1970s had an advanced university degree (85 per cent). Until the revolution of 1974, all governors had such qualifications; it was only after the establishment of a democratic regime that people with shorter university degrees or only secondary education were appointed civil governors. After this date, around 23 per cent of Portuguese governors in the South lacked higher-level university degrees. This situation had no parallel in Spain, where higher-level degrees (particularly in Law) were the norm until 1980. As for Portuguese governors, their professional profile until the 1970s was the following: 50 per cent specialists in intellectual and scientific professions; 17.9 per cent officers in the armed forces (with ranks mostly ranging from commander to lieutenant); 10.7 per cent civil servants; 7.1 per cent employed in education, and a further 7.1 per cent with technical bachelor’s degrees (bachelor’s in engineering); and 7 per cent other professions. Overall, governors in the Southern districts had a very similar breakdown, albeit with a lower percentage of professionals in the intellectual and scientific areas (45.8 per cent) and a much larger percentage of officers in the armed forces (29.2 per cent). Among professionals, there were a great deal of attorneys (and other legal professions), but there were also teachers, engineers, veterinarians, etc. Thus, the legal professions (attorneys, lawyers, and magistrates) were not as predominant in the Portuguese case as they were in Spain. The opposite was true regarding the military: in Spain, military men were scarce during the later years of the dictatorship and all but disappeared after 1977 due to the effects of the above-mentioned royal-decree act 10/1977 (8 February), which discouraged many officers from continuing to pursue a political career. In Portugal, by contrast, the military was endowed with the prestige resulting from its role in the recovery of political freedoms and considered a guarantee of democratization and political change. Indeed the number of military men at the front of civil governments was quite considerable during the Período Revolucionário em Curso (PREC), from April 1974 to April 1976.

In Spain more than in Portugal, being governor was usually a stepping-stone in a political career. Among the 12 governors in office between 1970 and 1974, we know that 5 had previously been municipal chamber presidents. As was also the case in Spain, those occupying significant local offices were often a recruitment pool for governors. They had local political experience, were well acquainted with the administrative machinery, had contacts among central powers, and were trusted by the government in a world in which the local sphere was subordinate to a centralized territorial organization. Every single Portuguese governor was dismissed after the Carnation Revolution, but this is not to say that their replacements were all “new men”. There were exceptions. Of the 18 appointed after 25 April, at least 2 had prior experience at the local level after the 1974 revolution: 1 as president of the administrative commission in Faro (1974-1975) and another as mayor in Moura, district of Beja (1978-1980). There was indeed a context of path-breaking change through revolution and such cases were obviously in the minority, but it is nonetheless noteworthy that they were appointed governors to the very same districts (Faro and Beja) in which they had held previous responsibilities.

Exceptions aside, the change in governors was much more profound in Portugal than in Spain, as befitting the sudden fall of the dictatorship in the former as opposed to its slow extinction in the latter. In Portugal, the dictatorship’s governors did not continue their political careers under the new democratic regime (as opposed to the Spanish case, where even president Adolfo Suárez had been civil governor in the 1960s). By contrast, many of the newly appointed Portuguese governors would go on to pursue later political careers. Three out of 18 returned to local politics in the same districts where they had been governors (something which was very rare in Spain), with 2 Setúbal governors elected municipal chamber presidents (in Barreiro and Setúbal) and another becoming municipal assembly president.

There are also considerable differences between the districts/provinces of each country in terms of governors’ occupation of representative offices at the national level. Around 40 per cent of the governors appointed in Spain between 1936 and 1975 were members of the Cortes at some point in their careers; in Portugal, however, only 23 per cent were members of the National Assembly (Parliament) between 1936 and 1974. This was largely a consequence of the large presence of mayors or labor guild presidents in the Spanish National Assembly, at the expense of other groups such as governors, as in Portugal only 13 per cent of mayors had been members of the National Assembly or the Corporate Chamber. The upshot is that before 1974 very few governors were politically promoted to postings in the Portuguese central government. Only 3 of them managed to become cabinet members, a striking contrast to the Spanish case, in which a considerably larger number rose to minister or even president of the government (Arias Navarro and Suárez). In the case of the Southern districts and provinces, the contrast was evident: whereas not a single one of these governors in Portugal was simultaneously a member of the National Assembly between 1970 and 1974, in the eight Andalusian provinces there were up to 15 governors appointed in the 1970s who were or had been members of the Cortes.[4]

However, after the Carnation Revolution the upward mobility of Portuguese governors into significant posts in legislative chambers experienced a considerable rise, whereas the opposite happened in Spain. Our figures leave little room for doubt: taking all Portuguese districts into account, 47.7 per cent of governors appointed after 1974 were members of the Constituent Assembly and the Assembly of the Republic, setting aside the fact that 5five of them even became ministers. As for the 18 Southern governors analyzed here, the percentage was 38.9. Yet it has to be taken into account that holding both offices simultaneously was not possible under either country’s democratic regimes. In this regard, Portuguese governors either went on to become assembly members after their posting or had to leave their seat in the assembly to become Civil Governor, but were not allowed to do both things at once. This slowly turned the post of civil governor into a second-tier position of trust, as was the case in Spain, where governors gradually lost powers until their disappearance (in 1997 for Spain and in 2011 for Portugal). As opposed to governors, locally elected authorities could hold other offices simultaneously, leading to greater political potential and even a greater degree of professionalization (Borchert, 2003).

The political action of governors in southern Spain and Portugal: similarities, differences, and a few conclusions

The above analysis allows us to establish significant differences between Spanish and Portuguese governors, despite the similarities between the two. This comparison is especially important to the period of political change experienced by both countries in the 1970s. It is worth highlighting that such differences were palpable both in the later years of each dictatorship and in the early moments of the two transitions to democracy. There is no doubt that both figures were the highest representatives of central powers in their districts and provinces. And in both cases, the need to balance the interests of the central government and those of local forces (institutional or otherwise) in a more or less harmonious manner was of paramount importance.

One key difference between Portuguese governors and Spanish ones was the longer duration of the former’s terms before 1974. This was probably connected to the position of Portuguese governors, who were closer to and more identified with their districts (of which they were indeed natives in many cases) and with a lower presence in national legislative chambers. It is in this framework that governors’ relations with their districts, and their popular perception, must be understood. Although respected figures, they seem to have been less so than their Spanish counterparts. In 1973 an open letter was published against the governor of Braga, Manuel Augusto de Ascenção Azevedo. Its author, the well-known opposition leader Santos Simōes, spoke out against the autocratic methods of the recently appointed governor, who had banned the celebration of a series of talks on infant mortality (which in Braga reached the staggering rate of 60.4 per thousand at the time). Santos Simões, a teacher and a politician, had been arrested in 1968 by the secret police PIDE (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado). The letter dealt a crushing blow from the start:

For most of the Portuguese people, the authorities’ acts of arrogance are so common to the country’s daily routine that they rarely surprise us, although a significant part of the population is now starting to refuse to accept them [Simões, 1973].

To our knowledge, nothing of the sort happened in Spain in those years. The press could deliver more or less veiled criticism of local authorities, but openly discrediting a civil governor in a signed publication was a dangerous line to cross. The somewhat majestic distance between a Spanish civil governor and the province he had been appointed to, including its local authorities, reflected his standing. Additionally, he was the Provincial Head of the Movimiento, whereas Portuguese civil governors were not presidents of the district commission of Acção Nacional. Hence, aside from the usual interlocutors, Portuguese civil governors also had to deal with the Party’s local authorities, a task further complicated by the fact that some governors had previously held local offices in the same districts. As an example, in 1972 the president of National Action (Acção Nacional Popular, the official government party since 1970) in Braga asked the new governor for dialog and mediation (Ruivo, 1972).

In both countries, governors’ public statements referenced respect toward and defense of local interests, but in Spain this was balanced with the supremacy of the central government, conveniently identified with the general interest or the nation as a whole. By contrast, in Portugal some governors even dared to criticize the general situation upon their inauguration. Such was the case of the Civil Governor of Évora, Sílvio Belford de Cerqueira, who criticized the state of charity policies, the staggering rural unemployment rate, and the healthcare and water supply systems (Cerqueira, 1937).

The political transformation that took place in both countries did not lessen these differences at all. In fact, the total replacement of Portuguese governors and the gradual replacement of their Spanish counterparts only accentuated the differences. The length of Portuguese governors’ terms grew shorter in comparison to those of Spanish ones, as political change was more rapid and originated in the very structures of the state, whereas Spain experienced a gradual transformation of its regime while preserving the stability of the state and its administrative bodies. The principle of unity of power was preserved in Spain, and governors retained their authority. In Portugal, on the other hand, it was not altogether clear where power resided in the months following 25 April, as provisional governments succeeded one another. In such exceptional circumstances, governors faced significant local instability. It was not necessary to bring the revolution to the districts: mobilization was heavy enough, particularly in the Southern districts, where a very intense activist movement arose and implemented an agrarian reform (Almeida, 2006, Almeida, 2013). Rather, what was needed was to suppress revolutionary spirits and maintain balance in the provinces. Civilians did not replace military men as governors until 1976, whereas in Spain officers of the armed forces had been gradually disappearing from such posts until their full elimination in 1977.

In both countries, governors were relatively successful in directing the flow of political change. There were no districts or provinces with enough instability to seriously endanger the transition to democracy. This is not to say that the consolidation of a democratic regime was never at risk, particularly in Portugal. Indeed, during the PREC the advance of Communism in Southern districts was perceived as a genuine threat. Governors in these districts, despite mostly being members of the Communist party themselves, grappled with serious difficulties in maintaining law and order. The temptation to slowly shape the regime into a Communist one was only definitively sidestepped after the coup of 25 November 1975, the intervention of President Francisco da Costa Gomes (1974-1976), and the stabilization efforts of President António Ramalho Eanes (1976-1986).

Aside from the particularities derived from the Portuguese revolution, there were few significant differences in 1974-1975 between provinces and districts in terms of the political action of civil governors in the relationship between the center and local spheres. Maintaining a balance between central powers and the periphery was the key goal in both countries. The overall uniformity of governors’ actions, despite the above-mentioned differences, is better understood if one takes into account the fact that most governors were content to perform their role as government appointees, fulfil their duties as best they could, keep their province or district calm, and convey guidelines from Madrid or Lisbon as accurately as possible, albeit with what appears to be a greater degree of “localism” in the Portuguese case.

Flexibility and adaptability were key traits. Indeed the same governor could conduct affairs quite differently in two different provinces or districts, be it due to determining local factors or in the application of government orders. One case was Seville, where governor José Ruiz de Gordoa y Quintana was broadly considered to identify with the Francoist dictatorship in which he had held various political offices. Gordoa had previously been governor in Navarra, playing a questionable role in the bloody events of Montejurra in May 1976. Despite this, between June 1976 and August 1977 he continued in office in Seville, loyally transmitting the guidelines set forth by Adolfo Suárez’s new government, promoting political reform, and preparing for the first general election after the legalization of political parties. He had served under Carrero Blanco and later Arias Navarro in both his terms, and was just as loyal in serving under Suárez to facilitate political change in Seville.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, M. A. (2006), A Revolução no Alentejo: Memória e Trauma da Reforma Agrária em Avis, Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, M. A. (2013), “Landlords, tenants and agrarian reform: local elites and regime transitions in Avis, Portugal, 1778-2011”. Rural History, 24(2), pp. 127-142. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, M. A. (2013), O Poder Local do Estado Novo à Democracia: Presidentes de Câmara e Governadores Civis, 1936-2012, Lisbon, Leya. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, M. A. (2014), Dicionário Biográfico do Poder Local em Portugal, 1936-2013, Lisbon, Leya. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, M. A. (2017), “The revolution in local government: mayors in Portugal before and after 1974”. Continuity and Change, 32(2), pp. 253-282. DOI: 10.1017/S0268416017000170. [ Links ]

BERNECKER, W. L. (1990), “Spain and Portugal between regime transition and stabilized democracy”. Iberian Studies, 19, pp. 32-56. [ Links ]

BORCHERT, J. (2003), “Professional politicians: towards a comparative perspective”. In J. Borchert & J. Zeiss (eds.), The Political class in advanced democracies. Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

CERQUEIRA, S. B. (1937), Discurso pronunciado pelo Exmo. Governador Civil de Évora, Eng. Sílvio Belford de Cerqueira no dia 24 de Agosto de 1937 na Sala Nobre dos Paços do Concelho da Cidade de Évora em Assembleia presidida por S. Exa. o Sr. Ministro do Interior, Dr. Mário Pais de Sousa, Estremoz, Tipographia Brados do Alentejo. [ Links ]

CERVELLÓ, J. S. (1995), La revolución portuguesa y su influencia en la transición española (1961-1976), Madrid, Nerea. [ Links ]

DIAMANDOUROS, N., Gunther, R. (ed.) (2001), Parties, Politics and Democracy in the New Southern Europe, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

DULPHY, A., YVÉS, L. (dirs.) (2003), De la dictadura à la démocratie: voies ibériques, Bruxelles, PIE-Lang. [ Links ]

DYSON, K. E. (1980), The State Tradition in Western Europe: A Study of an Idea and Institution, Oxford, Robertson. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, T. (2007), “Authoritarian regimes and pro-democracy semi-oppositions: the end of the Portuguese dictatorship (1968-1974) in comparative perspective”. Democratization, 14(4), pp. 686-705. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, T. (2014), “Rethinking pathways to democracy: civil society in Portugal and Spain, 1960s-2000s”. Democratization 22(6), pp. 1074-1104. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, T. (ed.) (2017), A Qualidade da Democracia na Europa do Sul, 1968-2016. Uma Comparação entre Espanha, Grécia, Itália e Portugal, Lisbon, Imprensa de Ciências Sociais. [ Links ]

FERNÁNDEZ, A. B. G. (2011), “La llegada de la democracia al Mediterráneo: las transiciones de Portugal, Grecia y España”. HAOL, 25, pp. 7-18. [ Links ]

FISHMAN, R. (1990), “Rethinking State and regime: Southern Europe’s transition to democracy”. World Politics, 42(3), pp. 422-440. [ Links ]

GOLDSMITH, M. (1996), “Normative theories of local government: a European comparison”. In S. King Desmond and G. Stoker (eds.), Rethinking Local Democracy, Basingstoke, Macmillan, pp. 174-192. [ Links ]

GONZÁLEZ FERNÁNDEZ, A. (ed.) (2015), “Las transiciones ibéricas”. Ayer, 99 (3). [ Links ]

HERRERA, A. (2007), La construcción de la democracia en el campo, 1975-1988, Madrid, Ministerio de Agricultura, pesca y Alimentación. [ Links ]

HERRERO TEJEDOR, F. (1962), La figura del gobernador civil y jefe provincial del Movimiento, Madrid, Nuevo Horizonte. [ Links ]

JAMIL, I., ASKVIK, S., HOSSAIN, F. (2013), “Understanding administrative culture: some theoretical and methodological remarks”. International Journal of Public Administration, 36, pp. 900-909. [ Links ]

LEMUS, E., ROSAS, F., VARELA, R. (2010), El fin de las dictaduras ibéricas (1974-1978), Sevilla, Centro de Estudios Andaluces. [ Links ]

LINZ, J. J., STEPAN, A. (1996), Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

LOUGHLIN, J., HENDRIKS, F., LIDSTRÖM, A. (eds.) (2011), The Oxford Handbook of Local and Regional Democracy in Europe, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

MEDINA, J. (1995), Democratic transition in Portugal and Spain. A Comparative View, Coimbra, Faculdade de Letras. [ Links ]

MUÑOZ, R. D. (1997), Acciones colectivas y transiciones a la democracia. España y Portugal, 1974-1977, Madrid, Instituto Juan March de Estudios Sociales. [ Links ]

ORTÍZ HERAS, M. (coord.) (2016), La transición se hizo en los pueblos. El caso de la provincia de Albacete, Madrid, Biblioteca Nueva. [ Links ]

ORTIZ, R. O., YUNUEN, R. (2000), “Comparing types of transitions: Spain and Mexico”. Democratization, 7(3), pp. 65-92. [ Links ]

PAGE, E. (1991), Localism and Centralism in Europe: the Political and Legal Bases of Local Self-Government, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

PONCE ALBERCA, J. (2012), “Poder, adaptación y conflicto. Gobernadores civiles e intereses locales en la España de Franco (1939-1975)”. In A. Segura, A. Mayayo and T. Abelló (eds.), La dictadura franquista: la institucionalización de un régimen, Barcelona, Universitat de Barcelona, pp. 96-109. [ Links ]

PONCE ALBERCA, J. (2014a), “Estado, poder y administración: los gobernadores civiles en la España contemporánea”. In F. de Sousa (coord.). Os Governos Civis de Portugal e a Estructuração Político-Administrativa do Estado no Ocidente, Porto, CEPESE, pp. 137-158.

PONCE ALBERCA, J. (2014b), “Establishing early Francoism: central and local authorities in Spain, 1939-1958”. In M. O. Baruch (dir.). Faire des choix? Les fonctionnaires dans l’Europe des dictatures, 1933-1948, Paris, Conseil d’État-EHESS, pp. 169-187.

PONCE ALBERCA, J. (2014c), “Más allá de Madrid: el tránsito político en las provincias tras la dictadura de Franco”. HISTORIA 396, 4(2), pp. 289-317.

PONCE ALBERCA, J. (2016), “Los gobernadores civiles en el primer franquismo”. Hispania. Revista Española de Historia, LXXVI, 252, pp. 245-271. DOI: 10.3989/hispania.2016.009. [ Links ]

PONCE ALBERCA, J. (2018), “La dictadura de Franco en las provincias: el poder de los gobernadores civiles”. In C. Cerón Torreblanca (coord.). Los límites del Estado: la cara oculta del poder local, Málaga, Universidad de Málaga, pp. 167-192. [ Links ]

RAPHAEL, L. (2008 [2000]), Ley y orden. Dominación mediante la Administración en el siglo XIX, Madrid, Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

RHODES, R. A. W. (1999), Control and Power in Central-local Government Relation, Aldershot, Ashgate. [ Links ]

RUIVO, J. M. M. (1972), Discurso da entrada na função do Governador Civil de Braga, Dr. Francisco Carlos Leite Dourado, Braga. [ Links ]

SÁNCHEZ, M. O. (2006), Adolfo Suárez y el bienio prodigioso, Barcelona, Planeta. [ Links ]

SÁNCHEZ, O. (2003), “Beyond pacted transitions in Spain and Chile: elite and institutional differences”. Democratization, 10(2), pp. 65-86. [ Links ]

SHAMA, R. D. (2002), “Conceptual foundations of administrative culture. An attempt at analysis some variables”. International Review of Sociology, 12, pp. 65-75. [ Links ]

SIMŌES, J. S. (1973), E, contudo, move-se. Carta-aberta ao Governador Civil de Braga, Guimarães. [ Links ]

TARROW, S. (1977), Between Center and Periphery. Grassroots Politicians in Italy and France, New Haven-London, Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Received at 13-09-2019. Accepted for publication at 14-02-2020.

[1] Spanish and Portuguese laws respectively: Ley 6/1997, 14 April 1997, de Organización y Funcionamiento de la Administración General del Estado y Decreto-Lei nº 114/2011, 30 November 2011.

[2] See El País, 17 December 1982. That year, a woman was appointed civil governor for the first time since the years of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939).

[3] See Real Decreto-ley 10/1977, 8 February regulating the public activities of armed forces members. Article 5th was mandatory for officers (Jefes, Oficiales, Suboficiales y clases profesionales); however, the highest-ranking officers (Oficiales Generales) could continue their political activity. For the officers affected by this law, the deadline to end their terms as civil governors was August 1977.

[4] Many of the Spanish civil governors were also members of the Francoist Cortes (procuradores en Cortes) under the dictatorship. Some of those former procuradores were also governors under the democratic transition, as in the cases of Enrique Martínez-Cañavate (governor in Jaén, 1975-1978) and Enrique Riverola (governor in Málaga, 1976-1978).