Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Análise Social

Print version ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.231 Lisboa June 2019

https://doi.org/10.31447/AS00032573.2019231.07

ARTIGOS

Corruption, governance, and Nigeria’s uncivil society, 1999-2016

Corrupção, administração, e a sociedade (pouco) civil nigeriana, 1999-2016

Ifeanychukwu Michael abada*, Elias Chukwuemeka Ngwu**

*Department of Political Science, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Enugu State. Nsukka Road, Nsukka, Nigeria. ifeanyi.abada@unn.edu.ng

**Social Sciences/Peace and Conflict Studies Unit, Department of Political Science, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Enugu State. Nsukka Road, Nsukka, Nigeria. elias.ngwu@unn.edu.ng

ABSTRACT

The interface between corruption and governance has been widely discussed, with corruption generally acknowledged as leading to poor governance outcomes. The intersection between the two is also generally believed to be a key driver of insecurity. This paper demonstrates that not only do corruption and bad governance drive conflict and insecurity, but that the latter often provide the cloaking for the perpetuation of corrupt and unaccountable governance. Using the Niger Delta militancy and the Boko Haram insurgency in South and Northeast Nigeria respectively as its units of analysis, the paper demonstrates the specific ways in which the activities of these uncivil society groupings led to the perpetration of large scale corruption and irresponsive governance in Nigeria during the period under study.

Keywords: governance; corruption; uncivil society; conflict; insecurity.

RESUMO

A confluência entre corrupção e governança tem sido amplamente discutida, sendo a corrupção geralmente reconhecida como fator conducente a fracos desempenhos administrativos. A interseção entre as duas é também amplamente considerada como principal propiciador da insegurança. Este artigo demonstra que a corrupção e a má governança não só geram o conflito e a insegurança, mas que esta última propicia frequentemente a cobertura necessária para a perpetuação de uma governança corrupta e impune. Utilizando a militância do Delta do Níger e a rebelião do Boko Haram no sul e no nordeste da Nigéria, respetivamente, como unidades de análise, este artigo explora os modos específicos pelos quais as atividades destes grupos da sociedade (pouco) civil conduziram à corrupção em larga escala e a uma administração irresponsável na Nigéria durante o período em análise.

Palavras-chave: administração; corrupção; sociedade (pouco) civil; conflito; insegurança.

INTRODUCTION

Right from Nigeria’s First Republic, the country has been bedeviled by enormous governance challenges and unbridled public sector corruption manifesting in poor governance outcomes and severe developmental pathologies. So pervasive has been the incidence of corruption that the various military coups that took place in Nigeria were justified on the grounds of massive looting of the public treasury by the civil political authorities to the detriment of the welfare of the majority of the citizens. However, no sooner had the various military administrations taken over the reins of governance than they too were embroiled in the miasma of corruption and unbridled plunder of public resources. Perhaps the most oft cited example of the military profligacy in Nigeria is the infamous Abacha loot which refers to the various sums of monies stacked away in foreign banks by the country’s late military Head of State, General Sanni Abacha, which is estimated to run into several billions of dollars.

It was widely hoped that the enthronement of democracy in 1999 would go a long way in addressing public sector corruption in Nigeria and in enhancing the quality of governance after decades of military pillaging of the economy and political brigandage. Such optimism, however, appears to have been largely misplaced. Nearly two decades of democratic experimentation in the country have yielded very meager returns in terms of curbing public sector corruption, enhancing accountable governance, and mitigating insecurity in the country. This is in spite of the efforts of several international development partners and domestic as well as international civil society organizations (CSO) and the enormous amount of resources being expended on fighting corruption and nurturing good governance in Nigeria.

The unabashed misuse of public resources and the failure of governance have engendered mass poverty in the country while the failure of civic engagement in tackling the numerous developmental and governance pathologies in the country has led to the emergence of uncivil society groupings that resort to the use of force in the expression of their discontent. Notable among groups that have adopted “uncivil” means in the pursuit of their demands are the Niger Delta militants and the Boko Haram insurgents. Both are distinguished by the latter’s use of extreme violence and the incoherence of its demands when it did make them. Both have been sources of insecurity in Nigeria during the period, albeit in varying degrees.

Published analyses of the interface among corruption, poor governance, and insecurity in Nigeria have amply highlighted the role of corruption and poor governance as drivers of insecurity. Their role in the emergence of such uncivil society groupings as the Niger Delta militants and the Boko Haram insurgents has also been broached. However, such analyses have largely ignored the reverse order causality between the activities of these uncivil society groupings on the one hand and the perpetuation of public sector corruption and poor governance in Nigeria on the other. This paper seeks to probe this neglected relationship. The paper argues that whereas poor governance and corruption intersect to engender insecurity and the ossification of uncivil society groupings as purveyors of insecurity, the activities of such groupings have provided the opaque environment for the perpetuation of corruption, which further erodes the capacity of the state to deliver on its social contract.

For clarity, the rest of the paper is presented in the following order: conceptual issues; theoretical perspective; the intersection of corruption and poor governance in Nigeria; corruption, governance, and Nigeria’s rising uncivil society; corruption and Nigeria’s Uncivil Society - A reverse order causality; summary and conclusion.

CONCEPTUAL ISSUES

CORRUPTION

Corruption is indeed a contested concept. So contested is this hydra-headed monster in Nigeria that top ranking members of Nigeria’s ruling elite have been unable to reach a consensus on its meaning, let alone the ways to combat it. To illustrate, the immediate past President of Nigeria, Dr Goodluck Jonathan, and Hon. Ekpo Nta, the Chair of the state anti-graft agency, the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC), both felt obliged to clarify the concept on two separate occasions in the past. On May 5, 2014 during his presidential media chart, while responding to allegations that he was not doing enough to curb corruption among his ministers, Jonathan claimed that most of what is referred to as corruption in Nigeria is not really that at all but “common stealing” (Obe, 2014, p. 1). Barely two weeks later, while addressing members of the Council for the Regulation of Engineering in Nigeria (COREN), Ekpo Nta, the ICPC chair, echoed the president’s stance stating that “stealing is erroneously reported as corruption” even by “educated” Nigerians (http://www.naijaurban.com/stealing-corruption-says-icpc/).

A year earlier, on May 16, 2013, while delivering a paper titled “Good Governance and Transformation” at a forum organized by the ICPC, the then Akwa Ibom state Governor and an influential member of President Jonathan’s ruling Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDP), Godswill Akpabio, had stated that “corruption ranges from stealing to inflation of contracts”. Corruption, he said, occurs “when leadership fails in the management of resources and lacks the ability and courage to plug loopholes in the economy” (http://www.premiumtimesng.com/opinion/134999-how-corruption-poor-governance-are-killing-nigeria-by-godswill-akpabio.html).

With such conceptual confusion within the top echelon of Nigeria’s ruling party at the time, it is little wonder that not much was done by way of articulating an appropriate strategy for fighting corruption in the country.

GOVERNANCE

The term governance is actually a very old one, but which has been revived recently, and became, perhaps, one of the most attractive concepts in social science, especially in the field of public administration (Lee, 2003). The term “governance” is often used as a synonym for government. In this sense, the World Bank defines it as “the manner in which power is exercised in the management of a country’s economic and social resources for development” (World Bank 1991, p. 1), and the World Governance Institute, WGI (2006) as the traditions and institutions by which authority in a country is exercised.

An alternate definition sees governance as the use of institutions, structures of authority and even collaboration to allocate resources and coordinate or control activity in society or the economy (Bell, 2002). In this sense, governance has come to signify “a change in the meaning of government, referring to a new process of governing; or a changed condition of ordered rule; or the new method by which society is governed” (Rhodes, 1996, pp. 652-53; Stoker, 1998, p. 17). The essence of governance, therefore, is its focus on governing mechanisms that do not rest on recourse to the authority and sanctions of government (Kooiman and Van Vliet, 1993, p. 64). The Mo Ibrahim African Governance Index measures governance using a set of indicators classified within four categories namely: Safety & Rule of Law; Participation & Human Rights; Sustainable Economic Opportunity; and Human Development (Mo Ibrahim Index, 2013).

CIVIL SOCIETY

The concept of civil society goes back to the Greek city states. It comes from the Latin civilis or “citizen”, which means a free member of the city. But its modern usage is traceable to 18th Century political theorists from Thomas Paine to George Hegel. The latter developed the notion of civil society as a domain parallel to but separate from the state (Cerothers, 1999). Alexis de Tocqueville developed this idea in greater depth, presenting it as “the sphere of uncoerced human associations between the individual and the state, in which people undertake collective action for normative and substantive purposes, relatively independent of government and the market” (Edwards, 2011, p. 9).

Although there is little agreement about its precise meaning, the term expresses the idea that human beings can realize their desire for freedom and liberty while living and working together. It became popular among the philosophers of the Enlightenment, who were looking for ways to eradicate absolutist rule and create a free society based on the “natural rights” of all human beings (Ben-Eliezer, 2015). Regardless of the disagreements over its precise meaning, civil society has come to be generally understood as the public space between the market and the state (Keane, 1988), where citizens can freely organize themselves into groups and associations at various levels in order to make the formal bodies of the state adopt policies consonant with their perceived interests within a framework of law guaranteed by the state (Pietrzyk, 2001 quoted in Johnson, n. d.).

In sum, civil society is the multitude of non-state organizations around which society organizes itself that may or may not participate in the public policy process in accordance with their shifting interests and concerns (USAID, 1999). The key features of civil societies have been identified as:

their separation from the state and the market; they are formed by people who have common needs, interests, values; they have their own systems and structures, with entrenched values, norms (tolerance, inclusion, cooperation, equality) and practices (principles of effectiveness, efficiency and sound financial management); they develop through a fundamentally endogenous and autonomous process, which cannot easily be controlled from outside [UNDP, 2002, p. 2].

Philippe Schmitter (1995) adds that “civil society is not a simple but a compound property which rests on four conditions or norms namely: (1) dual autonomy; (2) collective action; (3) non-usurpation; (4) civility” (For elaboration of the term as used by Schmitter, see Whitehead 2014, p. 100).

UNCIVIL SOCIETY

In contrast to the civility so closely associated with civil society, Adam Ferguson foreshadowed the idea of an “uncivil” society, which, according to him, is a space “inhabited by the savage’, the primitive’, the rude’, the aggressive’, or the fanatic’ other” (Ferguson, 1995 cited in Ben-Eliezer 2015, p. 171). Due to its lack of conceptual precision, the term “uncivil society” has been described as “a portmanteau term for a wide range of disruptive and threatening elements that have emerged in the space between the individual and the state and that lie outside effective state control” (Heine and Thakur, 2011, p. 4). This space, according to former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, embodies networks of terrorism, drug trafficking, and organized crime (Annan, 1998). Annan also described uncivil society as the “drivers of conflict”, those who “promote exclusionary policies or encourage people to resort to violence” (Beittinger-Lee, n. d, p. 207).

It has, however, been clarified that the USO (Uncivil Society Organizations) vary significantly and encompass groups ranging from “vigilantes, militias, paramilitaries, youth groups, civil security task forces and militant Islamic (and other religious) groups, ethnonationalist groups to terrorist organizations and groups belonging to organized crime” (Beittinger-Lee 2009, p. i). It has also been found that USO thrive best in social locations where civil society is weak or absent. In such situations, the reverse of Schmitter’s four conditions usually apply - namely (1) encroachments on dual autonomy; (2) which subvert the capacity for deliberation; and may encourage (3) usurpation; and (4) incivility (Whitehead, 1997, p. 104). It follows therefore that as Foley and Edwards (1996, p. 48) rightly observed:

Where the state is unresponsive, its institutions are undemocratic, or its democracy is ill-designed to recognize and respond to citizens’ demands, the character of collective action will be decidedly different than under a strong and democratic system. Citizens will find their efforts to organize for civil ends frustrated by state policy - at some times actively repressed, at others simply ignored. Increasingly aggressive forms of civil association will spring up, and more and more ordinary citizens will be driven into active militancy against the state or self-protective apathy [cited in Beittinger-Lee, 2009, p. 5].

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVE

This study is anchored on the theory of post-colonial state. This is in line with Beittinger-Lee’s (2009) postulation that civil society never stands alone and its position and role are crucially formed and determined by the other political actors, notably the state. It is the assumption of this paper that the nature of the state defines the character of associational life within the society, and that the nature of the Nigerian state was shaped in large measure by its colonial origin.

The theory of the post-colonial state emanated from the Marxian theory of the state, which arose as a counter to the proposition of the classical liberal theory that the state is an independent force and an impartial arbiter that not only caters to the overall interest of every member of the society but also regulates equitably their socio-economic transactions and processes. The Marxist theory of the state has been further developed and employed in the elucidation and understanding of the peculiarity of the neo-colonial state by scholars such as Alavi (1973), Ekekwe (1985), Ake (1985), Ibeanu (1998), and others. The major contention of these scholars is that the post-colonial state rests on the foundation of the colonial state, whose major pre-occupation was to create conditions under which accumulation of capital by both foreign and domestic bourgeoisie would take place through the exploitation of local human and other natural resources (Ekekwe, 1985). The post-colonial state is also constituted in such a way that it reflects and mainly caters to a narrow range of interests, the interests of the rapacious political elite in comprador and subordinate relationship with foreign capital (Ake, 1985). Consequently, the state in post-colonial societies is institutionally constituted in such a way that it enjoys limited independence from the social classes, particularly the hegemonic social class.

For Ibeanu (1998), due to the distinct colonial experience at the stage of “extensive growth” of capital in which they emerged, the colonial state did not strive for legitimacy since its raison d’ être was “principally for conquering and holding down the peoples of the colonies, seen not as equal commodity bearers in integrated national markets, but as occasional petty commodity producers…” (Ibeanu, 1998, p. 9). As a result, there was no effort made to:

…evolve, routinize and institutionalize principles for the non-arbitrary use of the colonial state by the colonial political class. And when in the post-colonial era this state passed into the hands of a pseudo capitalist class fervently seeking to become economically dominant, it becomes, for the controllers, a powerful instrument for acquiring private wealth, a monstrous instrument in the hands of individuals and pristine ensembles for pursuing private welfare to the exclusion of others [Ibeanu, 1998, pp. 9-10].

Since the postcolonial state was all-powerful, and there were few safeguards on how its tremendous power was to be used in a moderate and civil manner, groups and individuals take a great stock in controlling the power of the state (p. 11). Characteristically therefore, the postcolonial state puts a premium on politics, thereby relegating everything else, including associational life to it. These characteristics have therefore combined with one another, and with many others, in complex dynamics to undermine the Nigerian state’s capacity to discharge those fundamental obligations of a modern state, such as “socioeconomic provisioning, guarantee of fundamental rights and freedoms, ensuring law and order and facilitating peace and stability as preconditions for growth and development of citizens” (Jega, 2007, p. 119).

In the Nigerian situation, political exclusion, economic marginalization and social discrimination threaten the security of the citizens to such an extent that they regard the state as the primary threat to their survival. In desperation, the victimized citizens take the laws into their own hands as a means of safeguarding their fundamental values from the threat of unacceptable government policies. The decline of the state as the guarantor of protection and human security and its increasing role as “the creator of insecurity” (Nnoli, 2006, p. 9) resulted in the gradual militarization of associational life in the country and the production of negative social capital by non-state actors (Monga, 2009), often degenerating into militancy, insurgency, and outright terrorism. These, in turn, provide the cloaking for wanton pillaging of the nation’s resources through over-bloated defense budgets, extra-budgetary spending, as well as active connivance in the clandestine extraction of the nation’s natural resources by agents of the Nigerian state.

INTERSECTION OF CORRUPTION, POOR GOVERNANCE, AND INSECURITY IN NIGERIA

Public sector corruption in Nigeria has, rightly or wrongly, been portrayed as genetically inscribed. A Colonial Government Report (CGR) of 1947 on Nigeria attributed the propensity for corruption in Africa to Africans’ orientation to public morality by which “the African in the public service seeks to further his own financial interest” (Okonkwo, 2007 quoted in Ogbeidi, 2012, p.6). To lend credence to that assertion, two of Nigeria’s foremost nationalists, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe and Chief Obafemi Awolowo, were both found guilty of diversion of public funds to private or party use by two separate commissions of inquiry in 1956 and 1962, respectively (Ejovi, Mgbonyebi & Akpokige, 2013). Also, corruption was so rampant in the First Republic under the leadership of Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa that it provided the justification for the first military intervention in Nigerian politics. In the broadcast that ousted the First Republic on January 15, 1966, the coup leader, Major Chukwuma Nzeogwu, announced that:

Our enemies are the political profiteers, the swindlers, the men in high and low places that seek bribes and demand 10 percent; those that seek to keep the country divided permanently so that they can remain in office as ministers or VIPs at least, the tribalists, the nepotists, those that make the country look big for nothing before international circles, those that have corrupted our society and put the Nigerian political calendar back by their words and deeds [http://www.vanguardngr.com/2010/09/radio-broadcast-by-major-chukwuma-kaduna-nzeogwu-%E2%80%93-announcing-nigeria%E2%80%99s-first-military-coup-on-radio-nigeria-kaduna-on-january-15-1966/].

Corruption was similarly implicated in the broadcast that terminated Nigeria’s Second Republic on December 31, 1983, after barely four years of civilian rule (1979-1983). The spokesperson for the military junta, then Brigadier Sanni Abacha, declared thus:

You are all living witnesses to the great economic predicament and uncertainty, which an inept and corrupt leadership has imposed on our beloved nation for the past four years…. Our economy has been hopelessly mismanaged; we have become a debtor and beggar nation. Yet our leaders revel in squandermania, corruption and indiscipline [https://www.naij.com/920504-retro-series-buhari-first-launched-war-indiscipline-1984-video.html].

In spite of this eloquent summation and the promise of a military-led remediation, the problem of public sector corruption in Nigeria was instead further compounded and institutionalized during the 16 years of military rule that followed that broadcast. Abacha’s reign was, in fact, the most inglorious of those years. It was also during that period that the Ibrahim Babangida administration was reported to have failed to account for an estimated $12.4 billion accruing from additional earnings from Nigeria’s crude oil exports during the Gulf War.

Meanwhile, any hope of mitigation of corruption with the return to democratic rule in 1999 has since vanished as corruption has clearly become a social norm in both the public and private spheres. To its credit the Olusegun Obasanjo administration (1999-2007) set up the institutional framework to fight corruption through the establishment of various anti-graft agencies like the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC), the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), the Bureau for Public Procurement (BPP), as well as the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) through the NEITI Act, 2007 (Idris, 2013). In spite of these efforts, however, the 2007 Human Rights Watch Report on Nigeria’s criminal politics documented that Nigeria lost between US$4 billion and US$8 billion annually to corruption during the eight year tenure of Obasanjo (Shehu, 2011).

Similarly, under the Goodluck Jonathan administration (2009-2015), corruption was so rampant that even the president himself tried unsuccessfully to down play it through conceptual obfuscation as in his explanation during a media chart that what people called corruption was but “common stealing”. It is widely believed that such inarticulate responses to questions on corruption coupled with the clear lack of will by his administration to tackle the challenges of corruption largely cost him and his party victory in the 2015 general elections. Some of the more famous corruption allegations against his administration included the charge by his Central Bank Governor and the current Emir of Kano, Lamido Sanusi Lamido that the state oil company, NNPC, failed to remit US$20 billion of oil revenues into the state coffers.

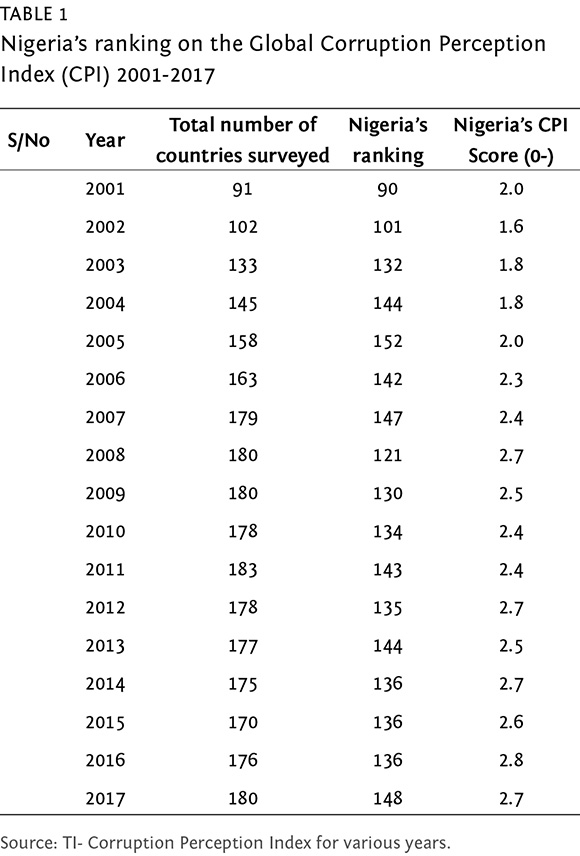

As a result of the mind-boggling corruption that has characterized governance in Nigeria over the years, the country has consistently performed poorly in major global corruption indicators.

Similar to Nigeria’s abysmal performance in major corruption indicators, the country has performed equally poorly in major governance indicators. In the Mo Ibrahim composite index for the decade 2006-2015, for instance, Nigeria ranked 36 out of 54 African countries. It recorded an average score of 46.5 out of 100 points over the ten year period. Whereas that score marked a 2.5% upward movement in Nigeria’s overall governance rating over the period (IIAG, 2016), the score falls short of the continental average of 50, and is even further below the regional average for West Africa which stands at 52.4 points and 3.1 percentage upward movement in the index. The three pillars of governance monitored by the IIAG are: Safety and Rule of Law; Political Participation and Human Rights; Sustainable Economic Opportunity.

Similarly, in the 2012 Open Budget Index Nigeria scored 16 out of a maximum 100 points as against her Anglophone West African neighbors of Ghana, Liberia, and Sierra Leone with scores of 50, 43, and 39 respectively. But perhaps more worrisome is that Nigeria’s rating has been falling since 2006, when the bi-annual study was first introduced. In the first edition, Nigeria scored 20 points, which dropped to 19 in 2008, then 18 in 2010 before reaching the all-time low score of 16 in 2012. And in the 2017 Open Budget Index, the country managed a score of 17 out of 100 with regard to budget transparency, 13 out of 100 for public participation in the budgetary process, and 56 out of 100 with regard to budget oversight, all of which fall far below the acceptable threshold for transparent budgeting.

Overall, corruption has been identified as the key driver of Nigeria’s governance deficit. Ogbuagu (2014) contends that despite periodic fluctuations in Nigeria’s major export (crude oil) prices, the country earns enough foreign exchange/revenue to “modernize” and provide infrastructural facilities to develop the economy. But rather than affecting the well being of the citizens through the provision of functional infrastructure, the oil earnings have merely led to the execution of ambitious and unviable projects that have served as a conduit for the emerging business class and the bureaucratic/political bourgeoisie to siphon public funds into personal pockets at the expense of infrastructural and human capital development (Atuanya, 2012).

It has been estimated that close to $400 billion was stolen from Nigeria’s public accounts from 1960 to 1999 (UNODC, 2007), and that between 2005 and 2014 some $182 billion was lost through illicit financial flows from the country (Hoffman & Patel, 2017). This figure represents some 15 per cent of the total value of Nigeria’s trade over the period 2005-2014, at $1.21 trillion, and in 2014 alone illicit financial flows from Nigeria were estimated at $12.5 billion, representing 9 percent of the total trade value of $139.6 billion in that year (Global Financial Integrity, 2017). This stolen common wealth in effect represents the investment gap in building and equipping modern hospitals to reduce Nigeria’s exceptionally high maternal mortality rates - estimated at 2 out of every 10 maternal deaths in 2015; expanding and upgrading an education system that is currently failing millions of children; and procuring vaccinations to prevent regular outbreaks of preventable diseases. Worse still, corruption tends to foster more corruption, perpetuating and entrenching social injustice in daily life. Consequently, such an environment weakens societal values of fairness, honesty, integrity, and common citizenship, as the impunity of dishonest practices and abuses of power or position steadily erode citizens’ sense of moral responsibility to follow the rules in the interests of wider society (Hoffman & Patel, 2017). It is little wonder then that the country is languishing in the 152nd position out of 188 countries and 22nd out of 53 African countries in the 2016 Human Development Index, which leaves her rooted in the Low Human Development (LHD) category, as against the Medium and High categories.

Corruption is also widely credited with fanning the flames of poverty, crime, and by extension, insecurity (Fagbadebo, 2007). Armed robbery, cultism, terrorism, disease, unemployment, and other factors that lead to insecurity have therefore been directly or indirectly linked to corruption (Dike, 2005; Ajodo-Adebanjoko & Okorie, 2014; Hoffman & Patel, 2017). In the Niger Delta region, where militancy first occurred, it has been attributed to political thugs who were initially recruited by corrupt politicians prior to elections in the region. These thugs who became idle after the elections had no other job but found one in the form of militancy, which eventually metamorphosed into bombing of oil installations and kidnapping of foreign oil workers for ransom (Ajodo-Adebanjoko and Okorie, 2014 p. 12). As with the Niger Delta, in the Northeast of the country, where the Boko Haram sect holds sway, many of the sect members were once political thugs. Corruption, therefore, encourages kleptocracy, breeds poverty and unemployment, and instigates as well as exacerbates conflicts. Transparency International similarly acknowledges the link between corruption and insecurity, noting that when a country’s institutions are weak, its security forces are not trusted and its borders are not strong and, as is the case in Nigeria, it gives terrorist organizations room to flourish.(http://ti-defence.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/2014-01_CorruptionThreatStabilityPeace.pdf).

CORRUPTION, POOR GOVERNANCE, AND NIGERIA’S UNCIVIL SOCIETY - A REVERSED CAUSALITY

In the preceding section we highlighted the orthodoxy in popular literature, where it is commonly held that corruption drives poor governance and that the two intersect to produce conflict and insecurity, through the activities of some uncivil society groupings like the Niger Delta militants and the Boko Haram insurgents in Nigeria. The missing link in the literature, which forms our point of departure, is to establish the reverse order causality among these variables whereby insecurity, as engendered the activities of these uncivil society groupings, provides the cloaking for the perpetration and perpetuation of corruption and demonstrate how both combine to aggravate governance and developmental pathologies and act as disincentive for the curbing of insecurity. We attempt to bridge this gap in knowledge by tracing the backflow channels through which the activities of these uncivil society groupings provide the cloaking for corruption to erode the capacity of the state to deliver the dividends of governance.

MILITANCY IN THE NIGER DELTA

Agitations for more equitable distribution of Nigeria’s oil wealth date back to the period immediately before the country’s independence and persisted all through the First and Second Republics as well as during the long years of military rule. However, agitation took a decidedly militant turn following two related incidents that occurred soon after the return to civil rule in 1999. The first was the rape of women and young girls that occurred in Choba in the oil-rich Rivers state in October 1999 and the massacre of civilians in Odi in adjoining Bayelsa state barely one month later in November 1999, both of which were sanctioned by the new civilian administration. Following those incidents, the atmosphere in the region, which was already supercharged by the murder of nine Ogoni human rights activists by the Abacha regime exploded. Any hope of a rapprochement between the inhabitants of the oil-bearing communities and the new civilian administration was dashed.

In response to the high-handedness of the new civilian administration as displayed in the two communities, the youths of the region declared armed confrontation against the Nigerian state and the Multinational Oil Companies operating in the region (Joab-Peterside, 2005; Ibaba, 2008). In quick succession, several militant groups sprang up in the region. These included: the Mujahedeen Asari Dokubo-led Niger Delta People’s Volunteer Force (NDPVF), Tom Ateke’s Niger Delta Vigilante (NDV), and the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND). NDPVF and MEND (created in 2005) were especially lethal in their execution of the “war” resulting in increased pipeline vandalism, kidnappings, and taking over oil facilities in the volatile Niger Delta (Badmus, 2010). Between January and December 2006, a total of 24 incidents, involving 118 hostages, comprising mainly Oil Company personnel, especially expatriate staff, had been recorded (Ibaba, 2008).

Following the outbreak of militancy in the Niger Delta, a Joint Military Task Force was drafted for the region by the Obasanjo administration to maintain law and order. The militarization of the region also coincided with the intensification of oil theft in the area. Though the theft of crude was first recorded in the region in the late 1970s and/or early 1980s, when the country was under military rule, the trade was probably small at that time (Katsouris & Sayne, 2013). So that both the scale of oil theft and allegations of connivance by Nigerian security forces in the illicit trade rose considerably in the aftermath of the outbreak of militancy in the region. In 2006, it was estimated that between 30,000 and 200,000 bbl/day were stolen from the area (Oudeman, 2006). The colossal loss of revenue to oil theft during the amnesty period was succinctly captured by Gaskia (2013) thus:

Over the past 3 to 6 years, in particular since the commencement of the presidential Amnesty programme for the Niger Delta, the subsequent inducement of a reduction in armed militancy in the region, and the consequent rise in the incidences of crude oil theft, we have been told by the highest responsible authorities (NNPC, Ministers of Finance and Petroleum Resources, CBN Governor etc) that the country has been losing outrageous quantities of crude oil to oil theft and pipeline vandalism [cited in Odalonu, 2015, p. 567].

In 2009 and 2010, the figures claimed ranged from 100,000 barrels per day to 200,000 barrels per day of crude oil. By 2012 this figure had risen to between 200,000 and 300,000 barrels per day of crude oil, and now the figure given for 2013 is 400,000 barrels per day of crude oil lost to oil theft (Odalonu, 2015 p. 567). In March 2006, a Brigadier General who was also a commander in the military Joint Task Force (JTF) operating in the Niger Delta was relieved of his post following allegations of involvement with illegal bunkering. Also, there were reports of ships engaged in oil theft passing freely through maritime check points, in full view of military patrols, and of even some rank-and-file JTF officers standing guard at illegal tap points and providing armed escort to ships loaded with stolen crude (Katsouris & Sayne, 2013).

There were also allegations of the collusion going all the way to the top of the state apparatuses with ships impounded by the JTF or navy having been allegedly released under political pressure, or gone missing altogether, only to resurface later repainted and reflagged. Also, over a dozen retired military officers who were arrested on suspicion of oil theft during the 2000s were all later freed without charge. There have also been reports of senior officers redeployed for refusing to engage in or turn a blind eye to oil theft (Katsouris & Sayne, 2013).

The point here is that even though oil theft preceded militancy in the Niger Delta, having been reported in the 1970s or 80s, the outbreak of militancy heightened the incidents of oil theft. Apparently, due to the volatility arising from the militancy in the area the ability of the security agencies to police the oil installations was hampered, and the ability of the hierarchy to effectively supervise the activities of their men could also be said to have been greatly encumbered, thereby leading to their high rate of connivance with the illegal oil bunkerers as reported above. But it is also the case that in the Niger Delta, violence and conflict are being used strategically to conceal entrenched looting and lucrative relationships (Jesperson, 2017) that permeate even the hierarchy. Jesperson insightfully predicted that in the event of conflict being no longer able to provide effective cover, there would likely be a resort to retaliation by vested interests.

A further illustration of the causal flow from militancy to massive corruption could be found in the implementation of the amnesty program instituted by the Nigerian state. In a bid to suppress militancy in the Niger Delta (the military solution having proved abortive) an amnesty program was instituted by the Umar Musa Yar’Adua administration on 25 May 2009. Under the terms of the amnesty program, youths from the Niger Delta who had taken up arms against the Nigerian state were granted unconditional pardon by the Federal Government upon surrendering their arms at designated points between August 6 and October 4, 2009. About 30,000 ex-agitators were reported to have accepted the FG amnesty program and surrendered their weapons, which included rocket-propelled grenades, guns, and explosives, before the deadline (Imongan & Ikelegbe, 2016). In return, the FG instituted a Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) package, which included various training and skill acquisition programs at home and abroad, and a N65,000 monthly stipend (Kuku, 2012).

The amnesty program no doubt restored a semblance of peace in the Niger Delta allowing for renewed optimal production and exportation of crude oil from the region. At the height of the conflict in 2009 Nigeria’s crude production had dropped from 2.2 million to 700,000 barrels per day (bpd). But following implementation of the amnesty program, crude oil production rose steadily to 1.9 million bpd in 2012, 2.4 million bpd in 2013, 2.6 million in 2014, and rose further to 2.7 million in 2015 (Amaize, 2016). The implementation of the amnesty program has been riddled with massive corruption, however. It has, for instance, been reported that in addition to giving some actors greater political standing and cover to engage in oil theft, the ceasefire conditions that came with the amnesty program created opportunity for the implementers of the program to engage in massive corruption and embezzlement of funds meant for the program (Katsouris & Sayne, 2013). In a July 10, 2015 petition to the then newly sworn in President Mohammadu Buhari, a civil society group, Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP), had requested the president to instruct appropriate government agencies to conduct a thorough investigation into allegations of corruption and denial of entitlement and allowances under the Niger Delta Presidential Amnesty Program. The organization was acting on the strength of a petition it received from Mr. Sukore O. Daniel, Mr. Ekperi Abel, Mr. Enodeh B. Eniyekperi, Mr. Ebaretonbofa J. Keme, Mr. Akperi Tamaraebi and Mr. Godspower A. Desmonds, all of Patani Community in Delta State. The petitioners alleged that they had gone through the required training under the Amnesty Program, and that although the Amnesty Office had issued identification cards to them and collected their bank details, they had not received the monthly payment of N65,000 due to them under the program from November, 2011 to the time of the petition (https://bizwatchnigeria.ng/serap-calls-investigation-corruption-niger-delta-amnesty-programme/).

Though such allegations were initially directed mainly at the implementers of the program during the Goodluck Jonathan administration, they have gained currency under the Buhari administration that rode to power on an anti-corruption mantra. In September 2017, for instance, Special Adviser to President Buhari on the Amnesty Program, Gen. Paul Boroh, was accused of stealing N6.2 billion from the Amnesty office using names of fictitious militants in the last two years. It was alleged, among other things, that in violation of a Presidential Directive instructing the payment of the monthly stipends of all Amnesty Delegates directly to their bank accounts, Gen. Boroh, in connivance with one Lt. Col. Okungbure CSO and their other associates, forged MOUs from Ghost Militants and Standing Payment Order to Banks. Boroh was also accused of awarding phony contracts for Agricultural Training and Empowerment to his Cronies, resulting in the siphoning of over N30 Billion within 12 months. Boroh allegedly enjoyed the backing of General Babagana Mohammed Monguno, the influential National Security Adviser to President Mohammadu Buhari (http://pointblanknews.com/pbn/exclusive/amnesty-boss-gen-boroh-in-n6-2-billion-scandal-nsa-monguno-fingered/).

Also, on February 4, 2018, stakeholders from the nine states of the Niger Delta petitioned the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) and the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission (ICPC) over alleged swapping of names of beneficiaries of the Presidential Amnesty Program (PAP). Under the aegis of Serving and Leading without Bitterness Initiative (SLWBI), the group listed some names and numbers of original beneficiaries of scholarships in several universities in the country, accusing the education desk of the program of removing the names and replacing them with those of their relatives. According to the petition signed by a certain Nature Keighe, Paulinus Albany, and Teke Iyala, aside from the swapping of names, much of the funds earmarked for the program were also diverted (https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2018/02/05/ndelta-group-petitions-efcc-icpc-over-alleged-racketeering-in-amnesty-programme/).

Following these and several other allegations, President Buhari in March 2018 sacked Boroh and replaced him with Prof. Charles Quaker Dokubo, a researcher with the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs (NIIA) while the anti-graft agency, the EFCC, commenced a probe of the Presidential Amnesty Program. Boroh has pleaded his innocence, insisting that he was a victim of intrigue orchestrated by corrupt elements in the government of President Muhammadu Buhari who, he said, wanted him to share “the spoils of office” among them. Even though unsubstantiated, Boroh’s claims lend further credence to the notion that militancy actually propels corruption.

Between 2009 and 2015, an estimated N234 billion had reportedly been spent on the amnesty program but allegations of lack of transparency and corruption in the process have been freely made by analysts. They argue that militants of lower cadres were short changed. Overall, it is believed that the Amnesty program has merely succeeded in enriching a powerful class of ex-militant “generals” that are primary beneficiaries of a war economy to the detriment of the rank and file (Olaniyi, 2015). Neither is it farfetched to conjecture that the militant bigwigs themselves may have been conduits for funneling monies into the accounts of some highly placed government functionaries. What is more, the terms of the deal between the Nigerian government and the militants left too much room for the militants to engage in illicit activities, particularly illegal oil bunkering, with minimal state interference.

INSURGENCY IN THE NORTH-EAST

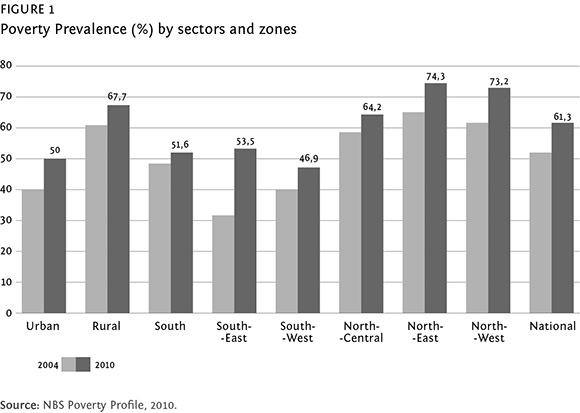

With respect to the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria’s Northeast where at one point 14 local government areas fell under the control of the Boko Haram insurgents, corruption and poor governance have famously been identified as the drivers of such violent conflict. In fact, the emergence of the insurgency is widely attributed to the poverty level, the dearth of infrastructure, and the high illiteracy level, as well as the high level of inequality in the zone. The National Bureau of Statistics, for instance, recorded that an average of 74% of the population of that region lives in absolute poverty (NBS, 2012 cited in Suleiman and Karim, 2015, p. 6), which is clearly above the national average.

In Borno state, where the Boko Haram group incubated and eventually blossomed, about 72 percent of children aged 6-16 never attended any school. This makes it a very fertile ground for recruitment and radicalization of foot soldiers by extremist groups like Boko Haram (Sule, Singh, & Othman, 2015). It is therefore beyond contestation that a direct link exists between the appalling human development situation and the festering insecurity in the region. It has been further argued that the link between corruption and violence arising in that corruption delegitimizes the state and fractures the relationship between government (state) and the people (society) and that it also “undermines the rule of law and the authority of the state, thereby leading to hostility by citizens who came to view the state as an enemy’” (UNODC, 2005, p. 89 cited in Sule, 2015, p. 39).

While the above submissions are absolutely correct, a close examination of recent events in Nigeria portrays a reversed causality between the activities of uncivil society groups such as the Boko Haram and the perpetuation of corruption in Nigeria. This aspect has clearly been understudied and therefore understated in the literature. To elaborate, since the coming into power of the Buhari administration, facts have come to light about the criminal diversion of astonishing amounts of money during the previous administrations in Nigeria in the guise of waging war against insurgency. Perhaps the most prominent case in point is the ongoing probe of the disbursement of the $2.1 billion arms cash by the Office of the National Security Adviser (ONSA) under President Jonathan in which it is alleged that money meant for the procurement of arms to prosecute the fight against insurgency in Nigeria’s Northeast was disbursed for political/electioneering purposes of the ruling party through the ONSA. This was happening even as thousands of innocent civilians and soldiers were being massacred by the dreaded organization.

Reports have it that due to the criminal diversion of money meant for the procurement of arms and the equipping of the military, Nigerian soldiers prosecuting the war against the insurgents were so short of resources at one point that “their weapons didn’t have bullets and their trucks didn’t have gas, resulting in high casualty rates and extremely low morale among the officers and men” (Schifrin, 2015, p. 1). By the personal account of a soldier who, together with his colleagues, was drafted to Borno state under the pretext that they were going to Mali to fight Al Shabab, they were dropped off in the war front with insufficient ammunitions and without any aerial or artillery back up. On each occasion they engaged the insurgents, the latter kept advancing while they (the soldiers) fired at them. The insurgents trampled on their dead and wounded as they advanced, with suicide bombers leading the charge. The insurgents would continue to advance until they (the soldiers) ran out of ammunition and fled. At that point, the insurgents would come after the fleeing soldiers, slaying them in their numbers and capturing some soldiers alive, with no rescue/operational vehicle in sight. According to the soldier’s narrative, some of the soldiers captured in the process were those that the terror group paraded in some of their video releases which have been aired in the media from time to time.

Meanwhile, aside from the lump sums obtained through extra-budgetary processes and allegedly diverted by the Office of the National Security Adviser, there has also been an astronomical rise in Nigeria’s defense budget since the outbreak and intensification of the Boko Haram insurgency. From 100 billion naira ($625 million) in 2010, budgetary allocation to the sector jumped to 927 billion naira ($6billion) in 2011 and 1trillion naira ($6.25billion) from 2012 to 2014 (ICG 2014, p.30 cited in Akume & Godswill, 2016). By this, over a period of four years the federal government of Nigeria budgeted about N3.38 trillion to combat insurgency and other security challenges in the country (Eme & Anyadike, 2013). But in spite of this, the insurgents were on the rampage all through that period, seizing territories, abducting women and children at will, and spreading their toxic ideology. Investigations have shown that the bulk of those monies appropriated for combating insurgency were actually misappropriated by top government, military and other security agencies’ officials in collaboration with politicians and contractors supplying military hardware (Akume & Godswill, 2016). In point of fact, it is now common knowledge that the fight against insurgency provided the cloaking for funneling huge sums of money to political party financing and other forms of political settlements.

Worse still, when we juxtapose these facts with the declaration made by then President Jonathan on January 8, 2012 that “some members of the sect were in the executive, legislative and judiciary arms of government as well as the armed forces” (Vanguard, January 9, 2012), it might not be farfetched, albeit conjecturally, to suggest that part of those monies may have actually circuitously ended up in the coffers of the insurgents, leading to the perpetuation of the insurgency and justifying further increase in defense budget and extra-budgetary allocations to the defense sector. In this sense, therefore, it can be seen that even though corruption and poor governance often combine to feed into insecurity and conflicts, it is a demonstrable empirical fact that militancy, insurgency, and other uncivil society activism have tended to instigate, feed into, and/or exacerbate corruption and poor governance.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

In this paper we highlighted through existing empirical literature the causal relationships among corruption, governance, and insecurity in which the direction of causality is generally believed to flow from corruption to poor governance and insecurity. The central concern of the paper, however, was to demonstrate that in addition to this direction of flow, there is often a reverse order relationship among these variables that has been understudied and therefore understated in analyses in which insurgency, militancy, and other uncivil society activism actually drive corruption, exacerbate governance pathologies and thereby compound the security challenges in a given polity. By this, we argued that even though poor governance and corruption are active drivers of violence and insecurity, situations do arise and have in fact often arisen, whereby violence and insecurity as perpetrated by various uncivil society groupings like the Niger-Delta militants and the Boko Haram insurgents in Nigeria provide the cloaking for the perpetration and perpetuation of corruption by agents of the state. And when this happens, as it often does, the capacity of the governing institutions to both curtail corruption and combat violent eruptions within the polity is greatly impaired. On the strength of evidence therefore, we surmise that the interface among these three variables are by no means linear and can only be fully comprehended by viewing them dialectically.

REFERENCES

AGBIBOA, D. E. (2013), “As it was in the beginning: the vicious cycle of corruption in Nigeria”. Studies in Sociology of Science, 4(3), pp. 10-21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3968/j.sss.1923018420130403.2640

AJODO-ADEBANJOKO, A., OKORIE, N. (2014), “Corruption and the challenges of insecurity in Nigeria: political economy implications”. Global Journal of Human-Social Science: F Political Science, 14(5), pp. 10-16.

AKE, C. (Ed.). (1985). Political Economy of Nigeria, London, Longman. [ Links ]

AKUME, A. T., GODSWILL, J. (2016), “The challenge of managing insurgency in Nigeria (2009-2015)”. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy, 7(1). DOI: 10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n1s1p145

ANNAN, K. (1998), Secretary-General Says United Nations Can Facilitate International Fight Against “Uncivil Society”. Text of the “magisterial lecture” delivered by Secretary-General Kofi Annan at the Foreign Ministry of Mexico on 23 July.

BADMUS, I. A. (2010), “Oiling the guns and gunning for oil: oil violence, arms proliferation and the destruction of Nigeria’s Niger delta”. Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences, 2(1), pp. 323-363.

BELL, S. (2002). Economic Governance and Institutional Dynamics, Melbourne, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

BEITTINGER-LEE, V. (2009), (Un)Civil Society and Political Change in Indonesia: A Contested Arena, London and New York, Routledge, Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

EJOVI, A., MGBONYEBI, V. C., AKPOKIGHE, O. R. (2013), “Corruption in Nigeria: a Historical Perspective”. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(16), pp. 371-386.

EKEKWE, E. (1985), “State and economic development in Nigeria”. In C. Ake (ed.), Political Economy of Nigeria, London & Lagos, Longman.

EKOTT, I. (2012), Ill-fated helicopter exploded before crashing, killing Yakowa, Azazi, four others, December 16. http://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/111388-ill-fated-helicopter-exploded-before-crashing-killing-yakowa-azazi-four-others.html [ Links ]

ENEGHALU, S. (2014), “Stealing Is Not Corruption” - ICPC Chairman, Ekpo Nta, May 19. https://www.360nobs.com/2014/05/stealing-is-not-corruption-icpc-chairman-ekpo-nta/

FAGBADEBO, O. (2007), “Corruption, governance and political instability in Nigeria”. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, 1(2), pp. 28-37. Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJPSIR.

FALANA, F. (2015), “Corruption. A State Policy Under IBB”. Nigerian Insight, February 12. http://nigerianinsight.com/corruption-a-state-policy-under-ibb/

GLOBAL FINANCIAL INTEGRITY (2017), Illicit Financial Flows to and from Developing Countries: 2005-2014, April 2017, http://www.gfintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/GFI-IFF-Report-2017_final.pdf, pp. 30-34 (accessed 4 May 2017). [ Links ]

HUME, N. J. (n.d.), “Uncivil encroachment - A political response to marginality in Jamaica”. Te Kura Kete Aronui Graduate and Postgraduate E-Journal - Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Waikato, vol. 1.

IBEANU, O. (1998), “The Nigeria State and the politics of democratization”. Paper Presented at a Conference for the Book Project on “Comparative Democratization in Africa: Nigeria and South Africa”, University of Cape Town, South Africa, 31 May-3 June.

IDRIS, M. (2013), “Corruption and insecurity in Nigeria”. Public Administration Research, 2(1), pp. 59-66. DOI: 10.5539/par.v2n1p59.

IMONGAN, E. O., IKELEGBE, A. (2016), “Amnesty programme in Nigeria: the impact and challenges in post conflict Niger delta, region”. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), 21(4), pp. 62-65. DOI: 10.9790/0837-2104076265

JESPERSON, S. (2017), Conflict Obscuring Criminality: The Crime-Conflict Nexus in Nigeria. United Nations University Centre for Policy Research Crime-Conflict Nexus Series: No 4 May. [ Links ]

KEANE, J. (1988). Civil Society and the State: New European Perspectives, London,Verso. [ Links ]

LEE, M. (2003), “Conceptualizing the new governance: a new institution of social coordination”. Presented at the Institutional Analysis and Development Mini-Conference, May 3rd and 5th. Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, Bloomington, Indiana University.

MAHDAVY, H. (1970), “The pattern and problems of economic development in rentier states: the case of Iran”. In M. A. Cook (ed.), Studies in the Economic History of the Middle East, Oxford, Oxford University Press,

MAKINDE, T. (2013), “Global corruption and governance in Nigeria”. Journal of Sustainable Development, 6(8).

MONGA, C. (2009), “Uncivil societies: a theory of sociopolitical change”. Policy Research Working Paper 4942, The World Bank Development Economics Policy Review Unit.

MOODY, J. (2016), Crackdown on Corruption Sparks Resurgence in Violence in Niger Delta. http://www.thisisafricaonline.com/News/Crackdown-on-corruption-sparks-resurgence-in-violence-in-Niger-Delta?ct=true [ Links ]

NNONYELU AU, N., UZOH, B., ANIGBOGU, K. (2013), “No light at the end of the tunnel: corruption and insecurity in Nigeria”. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 2(6), pp. 41-54.

ODALONU, H. B. (2015), “The upsurge of oil theft and illegal bunkering in the Niger delta region of Nigeria: is there a way out?”. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(3). DOI: 10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n3s2p563

ODISU, T. A. (2015), “Corruption and insecurity in Nigeria: a comparative analysis of civilian and military regimes”. Basic Research Journal of Social and Political Science, 3(1), pp. 8-15.

OGALA, E., UDO, B. (2012), Azazi Blames PDP for Boko Haram Attacks. http://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/4853-nsa_azazi_blames_boko_haram_attacks_on_pdp_s_politics_of_exclusi.html [ Links ]

OGBUAGU, U., UBI, P., EFFIOM, L. (2014), “Corruption and infrastructural decay: perceptible evidence from Nigeria”. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 5(10).

OSOBA, S. O. (1996), “Corruption in Nigeria: historical perspective”. Review of African Political Economy, 23(69), pp. 371-386.

SCHIFRIN, N. (2015), “Did corruption in Nigeria hamper its fight against Boko Haram?” December 27. http://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2015/12/27/461038854/did-corruption-in-nigeria-hamper-its-fight-against-boko-haram

SIVAKUMAR, N. (2014), “Conceptualizing corruption: a Sri Lankan Perspective”. International Journal of Education and Research, 2(4), pp. 391-400.

SULE, I., et al. (2015), “Governance and Boko Haram insurgents in Nigeria: an analysis”. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 4(2). DOI: 10.5901/ajis.2015.v4n2p35

SULEIMAN, M. N., KARIM, M. A. (2015), “Cycle of bad governance and corruption: the rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria”. SAGE Open, January-March 2015, pp. 1-11. DOI: 10.1177/2158244015576053 .

TAIWO, M. (2013), “Global corruption and governance in Nigeria”. Journal of Sustainable Development, 6 (8), pp. 108-117. DOI: 10.5539/jsd.v6n8p108

TANZI, V. (1995), “Corruption, arm’s-length relationship and market”. In F. Gianluca and S. Peltzman (eds.), The Economics of Organized Crime, Cambridge, Ms., Cambridge University Press, pp. 161-180.

TANZI, V. (1998), “Corruption around the world: causes, consequences, scope, and cures”. IMF Staff Papers, 45 (4). http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/FT/staffp/1998/12-98/pdf/tanzi.pdf,

UNDP (2002), “The role of civil society in local governance and poverty alleviation: concepts, realities and experiences”. A discussion paper for the Regional Workshop on Promoting Effective Participation of Civil Society in Local Governance and Poverty Alleviation in the ECIS Region - Challenges and Good Practices, Tirana 5-9 May.

UNODC (2007), “Anti-corruption climate change: it started in Nigeria”. Speech by Antonio Maria Costa at 6th National Seminar on Economic Crime, Abuja, 13 November 2007.

URI BEN-ELIEZER (2015), “The civil society, the uncivil society, and the difficulty Israel has making Peace with the Palestinians. Journal of Civil Society, 11(2), pp. 170-186, DOI: 10.1080/17448689.2015.1045697

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (2015), Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division, Geneva, WHO. [ Links ]

WORLDWIDE GOVERNANCE INDICATORS (2006), A Decade of Measuring the Quality of Governance. Governance Matters: New Annual Indicators and Underlying Data, Washington, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank www.govindicators.org. [ Links ]

Received at 10-07-2017.

Accepted for publication at 15-11-2018.