Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Análise Social

Print version ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.228 Lisboa Sept. 2018

https://doi.org/10.31447/AS00032573.2018228.03

ARTIGOS

Representations of Iberia at the turn of the 21st century in travel writing and social science: a quantitative approach

Representações da Península Ibérica na literatura de viagens e nas ciências sociais na viragem para o século XXI: uma abordagem quantitativa

Paulo Tiago Bento*

*Instituto de Humanidades, Artes e Ciências Jorge Amado, Universidade Federal do Sul da Bahia, Campus Jorge Amado, Rua Itabuna, s/n, Rod. Ilhéus–Vitória da Conquista, km 39, BR 415, Ferradas, Itabuna - CEP 45613-204, Bahia, Brasil. paulobento@ufsb.edu.br

ABSTRACT

Representations of Iberia at the turn of the 21st century in travel writing and social science: a quantitative approach. The importance of representations is discussed, prompting analysis of travel writing on Iberia. Portugal is portrayed as materially insufficient and as a traditional society. Spain shows up materially disadvantaged, significantly less traditional, and a non-harmonious society. Negative views predominate regarding both countries, with Spain's portrait depending mostly on a work shown as prejudiced. Scholarly depictions are used as benchmarks and explanations for mismatches discussed, including the worrisome possibility that travel writers may produce extremely negative portraits without an underlying prejudiced stance. Moral implications are found for travel writers and producers of representations in general.

Keywords: travel writing; representations; Portugal; Spain; quantification.

RESUMO

Discute-se a importância das representações, o que justifica uma análise da literatura de viagens sobre a Península Ibérica. Portugal é retratado como uma sociedade materialmente insuficiente e tradicional. Espanha surge como uma sociedade materialmente desfavorecida, significativamente menos tradicional e carecendo de harmonia. Predominam visões negativas relativamente a ambos os países, com o retrato de Espanha a depender sobretudo de uma obra que o artigo demonstra ser preconceituosa. São usadas como referência representações dos dois países produzidas no meio académico e são apresentadas explicações para as incongruências, incluindo a possibilidade preocupante de que os escritores de viagens possam produzir representações extremamente negativas ainda que a sua atitude não seja preconceituosa.

Palavras-chave: literatura de viagem; representações; Portugal; Espanha; quantificação.

INTRODUCTION

The influence of representations in tourism demand has been thoroughly researched (Beerli and Martín, 2004; De Jager, 2010; Galasin and Jaworski, 2003; Gilbert, 1999; Gorp and Béneker, 2007; Markwick, 2001; Nielsen, 2001; Pritchard and Morgan, 2001; Santos, 2004). Even novels raise the visibility of touristic places (Barnes and Cieply, 2012; Dunn, 2006; Ridanpää, 2011; Rojek, 1999), suggesting that non-fictional literature may be especially likely to play a significant role in the construction of touristic imagery because it tends to be taken as truthful (a “truth-effect”, as Kaplan puts it [1996, p. 54]).

Within non-fiction, travel writing is a special case in point. The genre is characterized by a horizon of expectation on the part of readers (Todorov and Porter, 1990, p. 18) that assumes the form of a pact of factual reading (Champeau, 2004). Within the pact of factual reading readers expect texts to correspond to what travel writers consider to be facts and direct experience, as opposed to the inventions of fictional writing. This means that travel writing plays a strong role in defining situations as real (Thomas and Thomas, 1928, p. 572). It may even influence country image (Mercille, 2005; Nadeau et al., 2008), shaping the competition for tourists that leads countries to engage in the same type of branding that companies adopt (Olins, 2000).

The relevance of travel writing as the focus of inquiry is reinforced by the fact that within studies of representations fiction is overwhelming, while non-fiction tends to be studied with focus on specific topics – for example, women (Karen and Cynthia, 2011) or death (Konstantinidou, 2007 and 2008). This raises the need for an open content analysis to contemporary travel writing, as performed by this study. Portugal and Spain are chosen because representations of these types of societies are not often studied.[1] Literature on representations of peoples and countries tends to focus on Western-produced representations of non-Westerns (as per Yan & Santos, 2009). Postcolonial studies (a major area studying representations) reproduce an East-West dichotomy or presume Europe or the West to be a homogeneous concept (Dainotto, 2007, p. 173). Moreover, research on touristic representations on peripheral countries has dealt mostly with former colonies of past imperial Western powers (as per Wang et al., 2009). Finnaly, tourism is an important economic activity in Spain and Portugal and the two countries are geographical neighbors and have strong historical and contemporary connections within the EU, making it interesting to compare images produced about them.

The relevance of travel writing also makes it important to gauge up to what point the pact of factual reading is being considered by travel writers. Knowing this is important per se and may be of use for represented countries and groups, as well as for the tourism industry, possibly prompting reactions from the countries represented and the industry. This study uses scholary productions as benchmark, assuming that they may be the most impartial kind of representation of otherness. This is because scientists are expected to be less biased in their approaches to the world, as they work within a kind of pact of factual reading of reality. Such an expectation creates potential sanctions for wrongdoing and influences individual behavior, even without the assumption of higher ethical standards on the part of scientists. In addition, science can also be considered less prone to the influences of sensationalism and breaking news than genres such as journalism and (literary) non-fiction.

Science has been criticized as a social construction in which results are a consequence of the social interactions between scientists (Latour and Woolgar, 1979). Arguably, though, science arises from a unique kind of social interaction comprised of mechanisms of peer review and collective, public examination of production processes, as noted by Bourdieu (2001). This is a type of social interaction underpinning the very publishing of this paper. For Bourdieu, scientists have as their main audience other scientists who are their competitors and have incentives to challenge them regarding their work. Science thus possesses a “vast collective equipment for theoretical construction and empirical validation or refutation” based on the “real as referee” [p. 52; my translations from the French original]. In contrast, (travel) writers are usually subject solely to the scrutiny of editors and, after publication, literary critics and the general public on the internet.

METHODOLOGY

In order to identify the images of contemporary Portugal and Spain circulating within travel writing, books published between 1986 (when both countries joined the European Economic Community, later European Union) and the mid-2000s were considered[2]. Short texts appearing in magazines or newspapers were excluded, assuming that they are less prone to contain patterns. Also, book writers tend to spend more time within host cultures as they need more experience to produce longer texts, implying a different experience vis-à-vis writers of shorter texts. Finally, writers of shorter texts are in some cases guests of tourism promotion authorities or tourist businesses when visiting a place and writing about it, with implications on their writing that do not apply to book writers.

Below is the list of the works on Portugal included in this study, which were the only ones matching the abovementioned criteria:

HEWITT, Richard (1999). Uma Casa em Portugal. Lisboa, Gradiva (originally published as A Cottage in Portugal, London, Simon & Schuster, 1996.

HYLAND, Paul (1996), Backwards Out of the Big World: Voyage into Portugal. London, Harper Collins.

LLAMAZARES, Julio (1998). Trás-os-Montes: uma Viagem Portuguesa, Lisboa, Difel.

PROPER, Datus C. (1992). The Last Old Place: A Search through Portugal, London, Simon & Schuster.

Works on Spain were:

ARENCIBIA, Franck (2003), Spain: Paradox of Values/Contrasts of Confusion – A Foreigner's Personal Perspective, New York, iUniverse.

CELA, Camilo Jose (1986), Nuevo viaje a la Alcarría, Barcelona, Plaza & Janes.

EVANS, Polly (2003), It's not about the Tapas: A Spanish Adventure on Two Wheels, London, Bantam Books.

FRANCE, Miranda (2001), Don Quixote's Delusions: Travels in Castilian Spain, London, Phoenix.

STEWART, Chris (1999), Driving Over Lemons: an Optimist in Andalucia, New York, Phanteon Books.

Regarding Spain, the books identified that matched the criteria were more numerous than for Portugal. Therefore, the choice was narrowed to a number of works matching the number of works regarding Portugal. Thus, the set of books on Portugal corresponds to the relevant (known) universe, while the set of books on Spain corresponds to a part of such universe. This should be kept in mind when considering the results and justifies a more detailed comparison between works on Portugal and scholarly work on the country. Aside from the restriction on number, works on Spain were chosen in order to encompass a varied set of authors. Authors include a famous writer (Camilo José Cela, Nobel Prize in Literature); a self-published one (Frank Arencibia); the author of a first work with an important publishing house (Chris Stewart); and two women writers (Miranda France, an earlier published travel writer, and Polly Evans, publishing with a division of the Penguin group).

Cela's fame has been shown to have important consequences, including enabling the author to change the very social and cultural landscape in which he travels (Bento, 2017. The inclusion of the opposite extreme of a self-published writer (Arencibia) will allow a preliminary test on what the circumstances of self-publishing may entail, considering that self-published travel books are rarely or never studied. On another dimension, the set of authors includes locals (Cela), expats (Arencibia and Stewart) and occasional visitors (France and Evans).

Although gender is not the focus of the present study, women were included to make the set of authors varied regarding gender. This is important because specificities are usually expected from women's travel writing. According to Siegel (2004, p. 1) critics have seen women's travel writing as less directed, less goal-oriented, less imperialistic, and more concerned with people than place. Besides, social expectations regarding women have a strong potential to influence women's experience and, therefore, their writing. Women might, for example, have easier access to feminine realms – and in some cases, even easier access to masculine realms (for example, in one of the works being studied, Miranda France writes that her pregnancy possibly provided a better access to a gypsy community).

A QUANTITATIVE APPROACH TO TRAVEL WRITING

It is usual for studies of texts to engage in implicit quantification by using words or expressions conveying quantity without quoting figures. Many such approaches also perform qualitative analysis by selecting parts of text considered to be significant. These are problematic ways of approaching texts, as Hoover (2008) notes on commenting on Virginia Woolf's novel To the Lighthouse:

Examples are rarely significant ( ) unless they are either unusual or characteristic of the novel or the author - otherwise why analyze them? And the unusual and the characteristic must be validated by counting and comparison: the bare claim that Woolf uses a great deal of personification [of objects] is without value and nearly meaningless unless it is quantified.

In trying to minimize such issues, this study adopted a quantitative approach rarely used in studies of texts (for example, Moretti [2005] uses the number of titles published to gauge the popularity of subgenres of the novel, but he does not deal with the contents of texts). In such a quantitative approach the selected works on Portugal and Spain were searched for all textual images, that is, descriptions and comments on the countries or parts of the countries. Each image was categorized into one or more categories called themes, allowing the identification of the themes with more images[3]. In turn, themes were then classified on the axis traditional society/modernity and used to work out a quantitative positiveness/negativeness index (as detailed below).

These processes amount to content analysis as “a technique that is applied to non-statistical material ( ) to analyze such material in a systematic way” (Finn et al., 2000, p. 134), using exhaustive, mutually exclusive and universal categories (Krippendorff, 1980). Arguably, an advantage of the quantitative approach adopted in this study over non-quantitative analysis of texts is a higher degree of systematization and a lower degree of overlapping. Moreover, all the categories used to classify images (the themes) are presented (below); this means that while subjectivity necessarily underlies both the identification of images and their categorization, the process is made more explicit, allowing for criticism and replication.

In identifying and quantifying the images, a set of rules was followed. First, there was no imposition of a biunivocal correspondence between excerpts of text and images. Second, to avoid ambiguity and reification, cases deemed unclear were ignored and long-chained interpretation avoided. Third, to each image was attached a degree of generality, a notion frequently used in studies on travel writing.[4]

Degrees of generality have usually been divided in the literature into the micro-level, the meso-level, and the macro-level (Turner, 2003), while Brante (2001) proposes five levels (international, interinstitutional, institutional, interindividual, and individual). Adapted from these approaches, this study uses the following framework:

Level 1 – Images that refer to an individual, a thing, a concrete situation, or similar.[5]

Level 2 – Images of a group, a community, a village, a city, or similar. This includes both circumstances in which face to face relations predominate and otherwise.[6]

Level 3 – Images of a country, a people, a society, a culture, or similar[7].

The concept of levels of generality allows for two types of analysis of the images. The first type, which does not consider degrees of generality, was called the external analysis and corresponds broadly to that of the reader, assumed to read for leisure. The second type, the internal analysis, is that of the researcher, who tries to analyze texts as systematically and encompassingly as possible, considering levels of generality. The internal analysis consisted of attaching a weight of 1 to each level 1 image, a weight of 2 to each level 2 image, and a weight of 3 to each level 3 image. Generality-weighted frequencies were then calculated for groups of images belonging to a theme or a cluster of themes (see below).

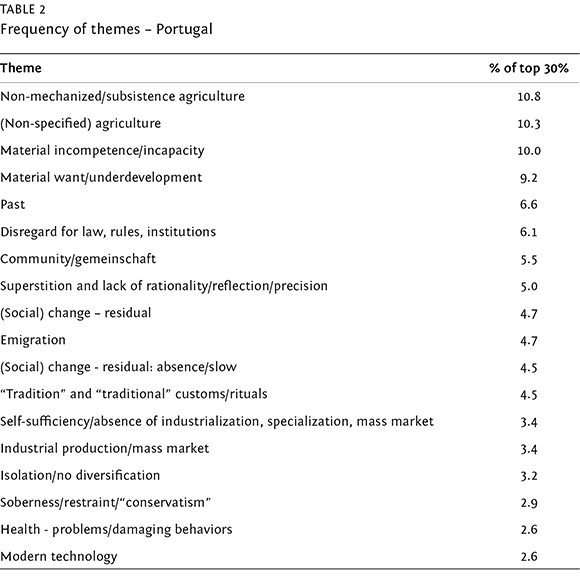

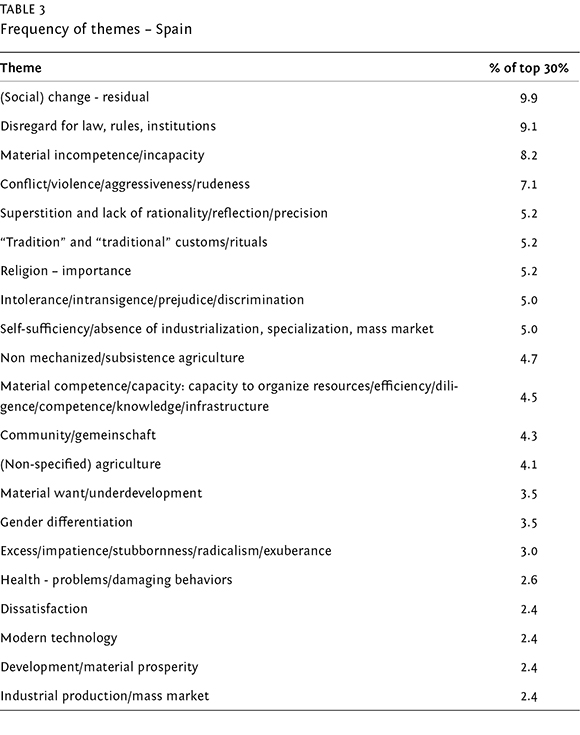

The most significant themes found are presented below. They are roughly the top 30% themes in terms of significance (that is, image frequency) and account for roughly 70% of total significance (details in results section). Definitions and examples of categorization of images into themes are provided for cases where such operation is not deemed straightforward.

• conflict/violence/aggressiveness/rudeness

• excess/impatience/stubbornness/radicalism/exuberance

• intolerance/intransigence/prejudice/discrimination

• disregard for law, rules, institutions (includes crime, dishonesty, reckless driving, and similar attitudes or behaviors)

• superstition and lack of rationality/reflection/precision

• “tradition” and “traditional” customs/rituals

The use of quotation marks above denotes a common sense use that corresponds largely to scientific use. The theme superstition and lack of rationality can be found, for example, in the “impenetrable logic” Hewitt sees in the Portuguese people (p. 12), but it is also inferred more indirectly in other cases – for example, after criticizing digging machines with rubber wheels, a local character in Stewart (p. 51) ends up by hiring one such machine, affirming: “You can't afford to be too fussy in these matters”.

• community/gemeinschaft (in opposition to society/gesellschaft)

• isolation/no diversification

Society and community are used in Tönnies's classical sense: small, relatively isolated integrated communities based upon primary relationships and strong emotional bonding versus the more anonymous and instrumental secondary associations of the modern metropolis (Featherstone, 1995).

• past

Past denotes the writer's experiences of aspects of otherness s/he deems belonging to a former period, either according to her/his personal background or at the level of (what s/he sees) as her/his own society. Underlying this theme is a linear vision of History that all societies go through the same developing stages, which is typical of 19th-century evolutionary anthropology but also frequent in travel writing (for example, in Nixon's (1991) notion of Conradian atavism, observed in Heart of Darkness, a journey up the Congo River moves backward through time, finding increasingly primeval humans). While emphasis on the past can be associated with a nostalgic mood, past differs from nostalgia (a theme with low found significance), as nostalgia refers to a mood noted on otherness by writers.

• self-sufficiency/absence of industrialization, specialization, mass market

• non-mechanized/subsistence agriculture

• (non specified) agriculture

• modern technology

Modern technology is contemporary with subsequent to the Industrial Revolution, obtaining power from sources other than humans, animals, or energy in its primary form (e.g. wind as opposed to electricity).

• industrial production/mass market

• development/material prosperity

• dissatisfaction

• emigration

• gender differentiation

• (social) change – residual

• (social) change – residual: absence/slow

Suffix residual in social change – residual, above, indicates that the theme does not encompass other themes denoting specific types of social change (an image of industrial production – decay implies social change, so that it was not double counted as social change – residual).

A NEGATIVENESS INDEX OF THE IMAGES

Regardless of the political/cultural location of an observer, some of the themes identified can be considered negative (desirable) or positive (undesirable), a distinction used, inter alia, in content analysis of news coverage of social groups (Dunn, 2003). An index of positiveness/negativeness of the images of otherness was calculated as number of images conveying positive themes minus number of images conveying negative themes per 10,000 words of the work to which each belongs. Besides this external analysis, an internal analysis was carried out, similarly calculating frequency-weighted indexes. The following rules were adopted: (a) exclusion of ambiguous themes meant excluding themes modern technology; industrial production/mass market; non-mechanized/subsistence agriculture; agriculture – absence/low level/decay (the latter could indicate industrialization and be positive for those seeing industrialization as positive). (b) the same applied to politically charged themes social equality; social inequality; liberal mores/liberalization of mores; gender differentiation; and to excess/impatience/stubbornness/radicalism/exuberance and modesty/low self-esteem (due to the ambiguity of modesty as positive or negative trait).

IMAGES OF TRADITIONAL SOCIETY AND MODERN SOCIETY

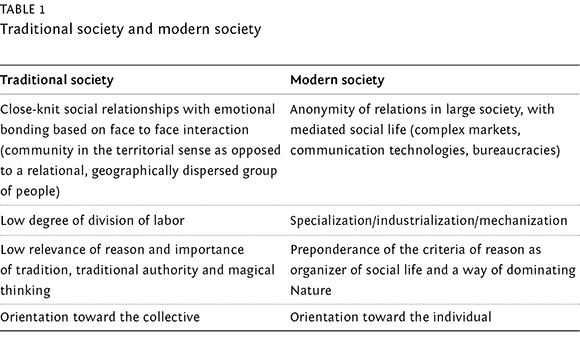

This study also analyzed how the countries were portrayed under the ideal-type pair traditional society/modern society (postmodernity being excluded given its high degree of generality[8]). For this, consideration was given to classic authors (Tönnies (quoted in Marshall & Scott (2009, p. 275)), Simmel (1950, quoted in Cresswell (2006, p. 17)); contemporary authors (Featherstone (1995), Bauman (1987), Calhoun (1992), Lowenthal (1999), Hollinger (1994); and social science manuals (Parker et al., 2003) (Table 1).

Religion is not considered an indicator of traditional society. For example, even though Inglehart (1997) speaks of a secularization process started with modernization, the United States of America, the third most populous country and according to the general view a non-traditional society, is highly religious (Putnam and Campbell, 2010, p.7).

TRAVEL WRITING AND SCHOLARLY WORK ON TURN OF THE 21ST CENTURY IBERIA: (MIS)MATCHES, EXPLANATIONS, CONSEQUENCES

1,294 images were identified, their distribution by themes following a slightly modified Pareto principle. A group of 30% of the themes account for roughly 70% of image frequency (number of images within a theme as percentage of total images). A group of 30% of the themes accounts for roughly 70% of total generality-weighted frequency.[9] Therefore, the description and discussion of results is focused on those 30% of themes. This means ignoring roughly 30% of significance and roughly 70% of themes, each of those themes with quantitative significance below 2%.

The four most frequent themes for Portugal (amounting to 40% of frequency), regard production and material circumstances. Excluding the theme (non-specified) agriculture because it is not necessarily an indicator of material insufficiency, we find that 30% of the themes identified convey a picture of material insufficiency (to which health – problems/damaging behaviors could be added). The three themes conveying material insufficiency (non-mechanized/subsistence agriculture; material incompetence/incapacity; material want/underdevelopment) are universally negative in the sense that any observer would accept them as such, with implications in the negativeness index (below). The theme countervailing this picture (industrial production/mass market) is offset by its opposite (self-sufficiency/non-industrial production ), as both show similar weight. Possibly related, the importance of emigration could be highlighting a causal mechanism in which writers observe the phenomenon resulting from the disadvantaged material position.

A group of themes amounting to 28% of frequency conveys a picture of traditional society. They are (separated by semicolons) past; community/gemeinschaft, self-sufficiency/absence of industrialization, specialization, mass market; “tradition” and “traditional” customs/rituals; superstition and lack of rationality/reflection/precision; and isolation/no diversification To these themes one could add soberness/restraint/“conservatism”, increasing the group's percentage to 30.5%. Such a theme reinforces the absence of change in Portugal: except for (social) change (residual category), no themes imply change – and the latter is offset by its opposite, with a similar percentage. Finally, disregard for law, rules and institutions ranks significantly sixth, matching the image of traditional society as a space where the State does not control the means of violence as in modern society (Weber, 1975). The Table below shows results for Spain.

Spain also shows up as disadvantaged in material terms, but significantly less so than Portugal. Themes material incompetence/incapacity; non-mechanized/subsistence agriculture; material want/underdevelopment; and health – problems make up 19% of the total. This compares with 30% in the neighboring country. Self-sufficiency/non-industrial production could be added to the group, increasing the total to 24%. Regardless of this inclusion, the frequency of the group is considerably lower than the equivalent for Portugal. Moreover, it is significantly counterweighted by themes material competence/capacity; modern technology; industrial production/ mass market; and development/material prosperity (which account for 12% of frequency).

Spain is also pictured as a traditional society in themes tradition and “traditional” customs/rituals; self-sufficiency/non-industrial production ; community/gemeinschaft; rationality /reflection/precision-absence ; and gender differentiation. However, the frequency of this cluster is 4.5 percentage points lower than for the equivalent cluster in Portugal and strongly counteracted by the frequency of the theme (social) change, the most important for Spain.

Disregard for law, rules, and institutions is more important than for Portugal. This is unexpected given, as argued for Portugal, in a less traditional society (as Spain is presented in the works being studied) the rule of law should be stronger. To accommodate this, to some extent one should consider that, together with conflict/ violence , Spain shows up as non-socially harmonious country (16.2% of frequency) and considerably different from Portugal in this regard (no themes regarding social harmony within the top 30%).

This conflict dimension pointed to Spain also helps in making sense of a group of qualities (nearing 10% of total frequency) that the authors being studied see in (the) people of the country: dissatisfaction and intolerance/intransigence/prejudice/discrimination; excess/impatience/stubbornness/radicalism/exuberance. Specifically, there could be a causal relationship from the last theme to the image of lack of social harmony. Santos and Rozier-Rich (2009) find that a set of mostly American writers resorts more to “dispositional factors” (personality-based explanation) when dealing with non-American places, associating that behavior with less knowledge of “situational factors” (or social cultural context). Similarly, the authors at hand could be explaining the lack of social harmony in Spain with the personality tendencies of Spaniards, instead of proposing causality in the opposite direction or a bidirectional one.

INTERNAL ANALYSIS OF THEMES

The above results do not change significantly in the internal analysis for Portugal, which extends the analysis to the generality of images. The first four major themes regard production and the material situation. Excluding again from this group the theme (non-specified) agriculture, insufficiencies in material terms persist (28% of generality-weighted frequency), to which self-sufficiency/non-industrial production could be added. Therefore, there is no significant difference between the internal and external analysis regarding the material situation.

The picture of pre-modernity is also confirmed in the internal analysis, accounting for 30% of total. This is slightly higher than in the external analysis due to the inclusion of the theme gender differentiation. Themes (social) change (residual category) and (social) change – residual: absence/slow roughly cancel each other out, but the picture of pre-modernity is not significantly eroded even when this cancellation is disregarded. A slight difference relative to the external analysis is the fact that health – problems/damaging behaviors is now absent from the top 30%, while disregard for law, rules, and institutions shows a slight reduction in significance.

The internal analysis for Spain continues to show a somewhat disadvantaged country in material terms (material want/underdevelopment and non-mechanized/subsistence agriculture, totaling 20%). Again, this could be considered reinforced by self-sufficiency/non-industrial production The major difference vis-à-vis the external analysis is that themes showing material sufficiency (now development/material prosperity and material competence/capacity) comprise only 3.8% of total generality-weighted frequency, down from 12% (mostly due to the absence of themes industrial production/mass market and modern technology). However, this reduction is comparable to the reduction in themes showing material insufficiency, so that the net picture in this regard does not change significantly.

Spain is still pictured as pre-modern in tradition and “traditional” customs/rituals; self-sufficiency/non-industrial production ; non-mechanized/subsistence agriculture; community/gemeinschaft; superstition and absence/low level of rationality ; gender differentiation and non-mechanized/subsistence agriculture. This cluster amounts to 24.6% of frequency, hardly a change from the external analysis. The pre-modernity cluster is still opposed by (social) change, now more salient as the most important theme for the country (12.6%) and also by liberal mores/liberalization of mores (2.1%), not previously showing within the top 30%. The overall picture in this regard is therefore slightly less pre-modern.

Although disregard for law, rules, and institutions does not greatly change its significance in the internal analysis, the cluster that includes this and the other themes conveying lack of social harmony now reach a significant 27.6% of the total (up from 16.2%). This reinforces the image of Spain as a not very socially harmonious country – in absolute terms and compared to Portugal. At the same time, the internal analysis sees the exclusion of (non-specified) agriculture; modern technology; and industrial production/mass market. The themes included are non-mechanized/subsistence agriculture; leisure (practice); liberal mores/liberalization of mores; and soberness/restraint/“conservatism”. Arguably, while the last two themes offset each other, they also make the representation of Spain more extreme from the internal point of view, matching to some extent the intensification of the representation of Spain as a non-harmonious society.

OVERALL COMPARISONS: MATERIAL CIRCUMSTANCES AND TRADITION/MODERNITY

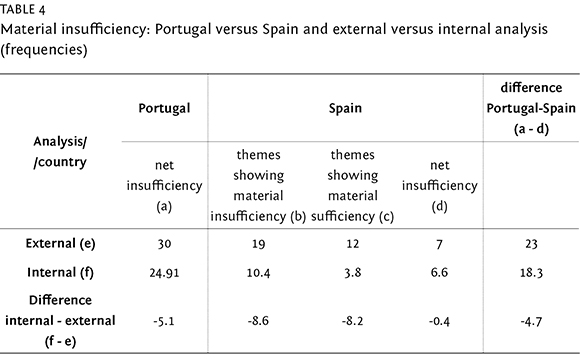

Table 4 summarizes the differences between Portugal and Spain considering material circumstances. Sufficiency indexes were calculated adding the frequencies of themes pointing to sufficiency and subtracting frequencies pointing to insufficiency (mutatis mutandis for generality-weighted frequencies). This resulted in net insufficiency for Portugal and net sufficiency for Spain, with Portugal's disadvantage slightly less intense in the internal analysis. Overall, the differences between the internal and the external analysis are not significant.

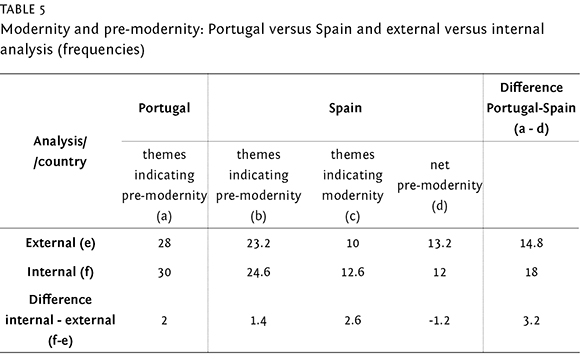

Table 5 summarizes differences between countries considering the axis traditional society/modern society. In the external analysis for Portugal, besides the theme (social) change – residual, there are no themes that may imply (social) change. In turn, this theme is offset by the its opposite, which shows a similar percentage. Therefore, there is no column for modernity (the same applying to the internal analysis). Overall, Portugal shows up as significantly more pre-modern than Spain, in both the external and internal analysis.

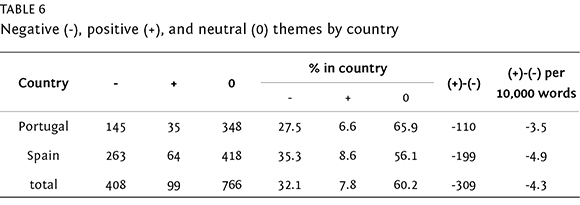

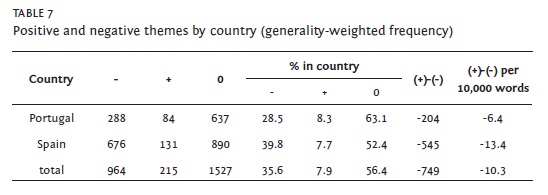

THE NEGATIVENESS INDEX

Table 6 shows in the last column the negativeness index for the external analysis. Negative views predominate regarding both countries, with Spain deemed more negative (40% greater than Portugal). The difference is magnified in the internal analysis (last column of Table 7), as Spain's negativeness index is now more than twice that of Portugal's.

The difference between Portugal and Spain depends greatly on the work of Frank Arencibia, though. In a scenario in which his work is excluded, Spain's negativeness changes to 60% of the negativeness for Portugal in frequency terms and to less than 50% in frequency-weighted terms. Arencibia'snegativeness is 3.3 times the average of the books under study in terms of frequency, with the other three works above average showing values of 45%, 22%, and 3% above the average . The difference is higher in terms of generality-weighted frequency (4.1 times against only one other work above average (41%)).

Considering a second scenario in which Arencibia is excluded from the analysis is justified given that its extreme negative content seems to stem in large part from a prejudiced attitude. This attitude is seen in structural characteristics not observed in the other works at hand. Arencibia often presents statistics conveying a negative view of Spain without comparison; when statistics are compared, Spain always leads in negativity; there is no single statistic showing Spain leading in a positive dimension; when positive images and negative images are simultaneously presented, negative images are presented last, leaving the impression that they predominate.[10]

SCHOLARLY VIEWS AND DISCUSSION

The above results show similarities and differences with the portraits produced by academic authors commenting on Portugal and Spain. Despite noting moves toward modernity, they see traditional cultural, political, and institutional influences persisting in Southern Europe (García and Karakatsanis, 2006). The area is also characterized by late industrialization and late introduction of market economy when compared with Northern Europe (Sapelli, 1995) and the Iberian neighbors are seen historically as semi-peripheral societies (Wallerstein, 1974).[11]

In the travel writing being studied, such dualisms can be seen reflected in the fact that Spain's top 30% themes show both themes under modernity and themes under pre-modernity. Differently from the scholarly views, though, pre-modernity predominates in Spain. In the case of Portugal, the travel writers tendency to convey premodernity – countervailing scholarly views – is clearer, as net pre-modernity is intense in both the external and internal analysis. The contrast becomes more striking considering that specific academic work on Portugal insists on the dualism in this matter. Barreto (1996) and Barreto and Preto (2000) see a clear, fast, economic and social modernization in the last decades of the 20th century, along with the persistence of insufficiencies and mismatches; some sectors and institutions have reached modernity and others are located at lower levels of development, the country showing both traces of First World and Third World.

In other dimensions there are similarities between the scholarly and travel writing approaches to the country. A second pattern of dualism found in scholarly writings is that in Portugal a significant part of individuals and families of rural extraction who changed their main activity to industry or services maintain small, family-run agricultural undertakings (Barreto, 1996), with more than one third of the families connected to the primary sector (Hespanha and Carapinheiro, 2001). This is well illustrated by a construction worker, described by Richard Hewitt, who promised to start working in three days because “the [planting of the] potatoes couldn't wait” (p. 8). More generally, themes related to agriculture – a visible cluster accounting for 15% of the images of top 30% themes (17.5% in the internal analysis) – also portray Portugal ambiguously within the axis modernity/pre-modernity.[12]

Within academic studies, Portugal is further considered to perform peripheral functions relative to the production and consumption patterns of core European countries, as shown by the hypertrophy of tourism and emigration (Sousa Santos, 1993). Correspondingly, the theme emigration is among the 12 most important in the top 30% for Portugal. Academic studies also see Portugal suffering from insufficiencies in the education system, noting that in the 1990s the illiteracy rate was still not residual as in most of Europe, while the development of the middle class and the improvement in consumption patterns did not have a positive influence in reading habits in Portugal (Barreto, 1996). Arguably, these visions are seen in themes material incompetence/incapacity; material want/underdevelopment; superstition and lack of rationality/reflection/precision (comprising 24% of frequency and 25% of generality-weighted frequency).

There is also a striking contrast between these travel writers and the UN's Human Development Index (HDI), according to which since 1980 Portugal and Spain have had “very high human development”[13]. A first, methodological explanation for this contrast is that, while the index considers most countries of the world, travel writers may be (implicitly) comparing the countries of Iberia with Western Europe or the Western World/First World, as the abovementioned scholarly views generally do. A second explanatory possibility is that all or some components of the HDI do not translate directly into a reality as could be experienced by travel writers, inter alia because the HDI addresses high(er) levels of generality. As Holland and Huggan (1998, 11) put it, travel writing “enjoys an intermediary status between subjective inquiry and objective documentation”. The genre is therefore differentiated in this regard from science, which is (ideally) located in the latter extreme of the opposition.

Travel writers are expected to rely on concrete images (or level 1, to follow the taxonomy presented above) more than social scientists. This is probable given the reader's supposed attraction to the narrative form, as stories are necessarily presented at this level. In the travel books at hand level 1 was actually the least used degree of generality (28.3% of images, against 30.6% and 41.0% for level 2 and level 3, respectively), but social scientists overwhelmingly stick with what would be levels 3 or 2 within the present framework. They resort to level 1 images as examples, anecdotal evidence or life histories, but the ultimate intention is to produce information and/or persuasion at levels 2 or 3, perhaps with the exception of anthropologists or very postmodern-oriented social scientists disliking grand or even middle range narratives.

Agency may also play a part in the difference between academic and travel writing textual productions. Specifically, while the horizons of expectation and the pact of factual reading of the genre may limit the extent of engagement with fiction, namely by endangering reputation if fictional liberties become known, such engagement has taken place, as was the case with travel writer Bruce Chatwin (Berndt, 1988). Even assuming that travel writers try to convey experience in their writings, they may themselves influence the kinds of experiences they are likely to have due to a priori general views, for example, by searching for cases that may illustrate those general views (Franck Arencibia, as noted above, is an extreme case of this). Scientists, in turn, are less prone to be involved in such high levels of subjectivity.

Travel writers may also be influenced by what they see as the expectations of their intended audience and follow them. At play here may be the influence of a hermeneutic circle of representation (Albers and James, 1988; Ryan, 2002; Caton and Santos, 2008), also called cycle of expectation (Nelson, 2007). In this, representations influence tourists to look for and confirm such representations when they gaze at the place or people, for example by photographing them (Jenkins, 2003; Stylianou-Lambert, 2012). Travel writing is expected to follow, in part, such clichéd representations (Dann, 2001) given that it caters to a significant extent to tourists.

Specifically, a non-prejudiced approach induced by the imagined audience may shape travel writing away from what the writer may actually experience, and also help to explain differences between travel writing and scholarly works. Under this approach, writers (and producers of representations in general) select mostly dimensions of reality where they find greater differences vis-à-vis their own societies. In doing so, they would try to satisfy the supposed preferences of audiences in such societies, who would mostly favor finding difference within otherness. For example, Sugnet (1991, p. 75) holds that Granta “magazine's overall coverage [of Africa], with its emphasis on disaster and bizarre behaviour, is probably even worse than mass media coverage”. Hence, an author may focus on dimensions in which difference prevails and produce an extreme general portrait. Where this portrait is a negative one, one finds the unexpected and worrisome result that it originates, at least partially, from a non-prejudiced point of view.

CONCLUSIONS

This study focused on the much ignored subject of recent travel writing on non-colonized societies. It sought to highlight in a systematic way portraits of Spain and Portugal circulating within the genre, considering that its truth-effect has important implications in the attraction of tourists, investment, and even in soft power. To achieve this goal, it identified all the images within a set of texts making up a relevant universe. Those images were codified into themes based on a frame of analysis interactively derived from the text and from social science concepts. This was intended to prevent the researcher from engaging in what would be a more subjective personal selection of certain kinds of themes. This reduction of subjectivity and the goal of exhaustiveness were deemed important methodological principles to render what readers might be finding in travel writing, although the intensity of images was not considered.

In addition to this emulation of the general perspective of readers (the external analysis), a perspective specific to the researcher (the internal analysis) was applied to consider the generality level of images. This implied codifying themes into groups defined by the researcher (material sufficiency, traditional society versus modern society and negativeness), following a cautious approach so that ambiguous and culturally/politically charged themes were left out of the analysis.

The application of this methodology found, in both the external and internal analyses, that Portugal is portrayed as insufficient in material terms and, fittingly, mostly as a traditional society. Spain also shows up as materially disadvantaged and traditional, but significantly less so. There is also the more pronounced difference that Spain shows up as a non-harmonious society, not the case for Portugal. Negative views predominate regarding both countries, but more on Spain, and the difference is greater in the internal analysis.

Spain's negativeness, though, was shown to be much dependent on a single work (that of Arencibia), prompting a qualitative inquiry that found it to be to some extent prejudiced. Such radicalism and the probably related fact that it is a self-published work (probably impacting readers less than the other travel writers) justified an additional analysis. Excluding Arencibia's work from the set of books under analysis made Spain much less negative in absolute terms and less negative relative to Portugal.

Adapting Dunn's (2003) proposition of promoting alternative representations of unfairly represented groups, tourist authorities and other stakeholders in the country may wish to engage in activities to counteract some aspects of these portraits produced by travel writers. As a possible contribution to that, this study compared the representations of the two countries produced by travel writing with the portraits produced by academic authors on Iberia in the same period, based on the assumptions that science is the most trustful discourse.

The portraits produced by scientists see a dualism between traditional society and modern society in Southern Europe, which can be seen reflected in the fact that Spain's most important themes regard both modernity and pre-modernity. In the case of Portugal, travel writers' tendency to convey pre-modernity is clearer, countervailing region- and country-specific scholarly views.

A more striking contrast was observed between the travel writing studied and the UN's Human Development Index, according to which since 1980 Portugal and Spain have had “very high human development”.

Such mismatches led to the proposition of explanations, the testing of which could be the base of future work on travel writing and of arguments by the Iberian tourism industry and other stakeholders. Agency is certainly at play here, influencing the kinds of experiences travel writers are likely to have due to a priori views and selecting/excluding experiences from texts, but more general explanations are also possible. First, in gazing at Iberia, travel writers make (implicit or explicit) comparisons with their own societies, while scientists are more encompassing. Second, having (usually) a high degree of generality, the objects of inquiry of scientists do not correspond neatly to the reality experienced by travel writers; moreover, travel writers tend to present images with low levels of generality considering their intended audience's attraction to stories. Finally, the intended audience may also imply an orientation by writers in which only dimensions in which the writer finds greater differences vis-à-vis her/his own society are considered. This raises the disturbing possibility of extremely negative portraits being made without an underlying prejudiced stance, to which the tourism industry should pay special heed.

These influences on the production of travel writing suggest how, even limited by the pact of factual reading and the horizons of expectation of the genre, its practitioners may be producing unrepresentative images of societies. Given the potential influence of representations in shaping attitudes and behaviors toward societies, an ethics of responsibility (Weber, 1975) could therefore be demanded of travel writers – and, more generally, of any producer of representations. Such ethics would try to be aware of all the abovementioned factors, noting that even an honest rendering of experience may not be sufficient.

In fact, even an honest rendering of a set of totally random experiences (e.g., depending solely on the people a writer finds on the way by chance supposing s/he also moves by chance) could face the problem of sample representativeness, given that on the move interactions between writers and people tend to be short(er). This places travel writing in a problematic epistemological position. Inspired by science, travel writers could try to overcome the issue (and some already do) by following many anthropologists and other social science practitioners who spend long periods within the people they study. In addition, as mentioned above, they should critically consider their own approaches and the very productions of social science.

REFERENCES

ALBERS, P., JAMES, W. (1988), “Travel photography: a methodological approach”. Annals of Tourism Research, 15 (1), pp. 134-158.

BARNES, B., CIEPLY, M. (2012), “New Zealand's hobbit trail”. The New York Times.Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/07/travel/new-zealands-hobbit-trail.html.

BARRETO, A. (ed.) (1996), A Situação Social em Portugal, 1960-1995, Lisbon, Imprensa de CiênciasSociais. [ Links ]

BARRETO, A., PRETO, C.V. (2000), A Situação Social em Portugal, 1960-1999: Indicadores Sociais em Portugal e na UniãoEuropeia, Lisbon, Imprensa de CiênciasSociais. [ Links ]

BARROW, J. (1968), An Account of Travels into the Interior of Southern Africa, in the Years 1797 and 1798, New York, Johnson Reprint. [ Links ]

BAUMAN, Z. (1987), Legislators and Interpreters, Oxford, Polity Press. [ Links ]

BEERLI, A., MARTÍN, J.D. (2004), “Factors influencing destination image”. Annals of Tourism Research, 31 (3), 657-681. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2004.01.010.

BENTO, P. (2017), “Substantial authenticity, (post/)modernity and transformation of otherness: the second trip of Camilo José Cela to the Alcarria”. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 15 (1), pp. 37-58.

BERNDT, C. (1988), “Review of the songlines”. Parabola, 13 (1), pp. 130-132.

BOURDIEU, P. (2001), Science de la science et réfléxivité, Paris, Raisons d'Agir. [ Links ]

BRANTE, T. (2001), “Consequências do realismo na construção de teoria sociológica”. Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas, 36, pp. 9-38.

CALHOUN, C. (1992), Habermas and the Public Sphere, Cambridge, MIT Press. [ Links ]

CATON, K., SANTOS, C. (2008), “Closing the hermeneutic circle? Photographic encounters with the other”. Annals of Tourism Research, 35 (1), pp. 7-26.

CHAMPEAU, G. (2004), “El relato de viaje, un génerofronterizo”. In G. Champeau (ed.), Relatos de viajes contemporáneospor España y Portugal, Madrid, Verbum, pp. 15-31.

CRESSWELL, T. (2006), On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World, New York, Routledge. [ Links ]

DAINOTTO, R.M. (2007), Europe (in Theory), Durham, Duke University Press. [ Links ]

DANN, G. (2001), “The self-admitted use of cliché in the language of tourism”. Tourism Culture & Communication, 3 (1), pp. 1-14.

DE JAGER, A. E. (2010), “How dull is Dullstroom? Exploring the tourism destination image of Dullstroom”.Tourism Geographies, 12 (3), 349-370. DOI: 10.1080/14616688.2010.495757.

DUNN, D. (2006), “Imagining Alexandria: sightseeing in a city of the mind”. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 4 (2), pp. 96-115.

DUNN, K. (2003), “Using cultural geography to engage contested constructions of ethnicity and citizenship in Sydney”. Social & Cultural Geography, 4 (2), pp. 153-165.

FEATHERSTONE, M. (1995), Undoing Culture: Globalization, Postmoderism and Identity, London, Sage. [ Links ]

FINN, M., WALTON, M., ELLIOTT-WHITE, M. (2000), Tourism and Leisure Research Methods: Data Collection, Analysis, and Interpretation, Harlow, Longman. [ Links ]

GALASIN, D., JAWORSKI, A. (2003), “Representations of hosts in travel writing. The Guardian travel section”. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 1 (2), pp. 131-149.

GARCÍA, M., KARAKATSANIS, N. (2006), “Social policy, democracy, and citizenship in Southern Europe”. In G. Richard, P. Diamandouros and D. Sotiropoulos (eds.), Democracy and the State in the New Southern Europe, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 87-134. DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199202812.003.0003.

GILBERT, D. (1999), “London in all its glory - or how to enjoy London': guidebook representations of imperial London”. Journal of Historical Geography, 25 (3), 279-297. DOI: 10.1006/jhge.1999.0116.

GORP, B., BÉNEKER, T. (2007), “Holland as other place and other time: alterity in projected tourist images of the Netherlands”. GeoJournal, 68 (4), pp. 293–305. DOI: 10.1007/s10708-007-9085-9.

HALL, S. (1992), “The question of cultural identity. In S. Hall, D. Held, T. McGrew (eds), Modernity and its Futures, London, Politic Press/Open University Press.

HESPANHA, P., CARAPINHEIRO, G. (eds.) (2001), Risco Social e Incerteza, Porto, EdiçõesAfrontamento. [ Links ]

HOLLAND, P., HUGGAN, G. (1998), Tourists with Typewriters: Critical Reflections on Contemporary Travel Writing. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

HOLLINGER, R. (1994), Postmodernism and the Social Sciences: a Thematic Approach, London, Sage. [ Links ]

HOOVER, D. (2008), “Quantitative analysis and literary studies”. In S. Schreibman, R. Siemens, A Companion to Digital Literary Studies, Oxford, Blackwell, retrieved from http//www.digitalhumanities.org/companionDLS.

INGLEHART, R. (1997), Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

JENKINS, O. (2003), “Photography and travel brochures: the circle of representation”. Tourism Geographies, 5 (3), pp. 305-328.

KAPLAN, C. (1996), Questions of Travel: Postmodern Discourses of Displacement. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

KAREN, R., CYNTHIA, C. (2011), “Women and news: A long and winding road”. Media, Culture & Society, 33 (8), 1148-1165.

KONSTANTINIDOU, C. (2007), “Death, lamentation and the photographic representation of the other during the Second Iraq War in Greek newspapers”. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 10 (2), pp. 147-166.

KONSTANTINIDOU, C. (2008), “The spectacle of suffering and death: the photographic representation of war in Greek newspapers”. Visual Communication, 7 (2), pp. 143-169.

KRIPPENDORFF, K. (1980), Content analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology, Beverly Hills: Sage. [ Links ]

LATOUR, B., WOOLGAR, S. (1979), Laboratory Life: The Social Construction of Scientific Facts. Beverly Hills, Sage Publications. [ Links ]

LOWENTHAL, D. (1999), The Past is a Foreign Country, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

MARSHALL, G., SCOTT, J. (2009), Dictionary of Sociology, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

MARKWICK, M. (2001), “Postcards from Malta: image, consumption, context”. Annals of Tourism Research, 28 (2), 417-438. DOI: 10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00049-9.

MERCILLE, J. (2005), “Media effects on image: The case of Tibet”. Annals of Tourism Research, 32 (4), 1039-1055. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2005.02.001.

MORETTI, F. (2005), Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History, London, New York, Verso. [ Links ]

NADEAU, J. et al. (2008), “Destination in a country image context”. Annals of Tourism Research, 35 (1), pp. 84-106.

NELSON, V. (2007), “Traces of the past: the cycle of expectation in Caribbean tourism representations”. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 5 (1), pp. 1-16.

NIELSEN, C. (2001), Tourism and the Media: Tourist Decision-Making, Information, and Communication, Melbourne, VIC, Hospitality Press. [ Links ]

NIXON, R. (1991), “Preparations for travel: the Naipaul Brothers' Conradian atavism”. Research in African Literatures, 22 (2), pp. 177-190.

OLINS, W. (2000), “Why companies and countries are taking on each other's roles”. Corporate Reputation Review, 3, pp. 254-265.

PARKER, J. et al. (2003), Social Theory – A Basic Tool Kit, Houndmills and New York, Palgrave McMillan. [ Links ]

PARSONS, T. (1949), The Structure of Social Action: A Study in Social Theory with Special Reference to a Group of Recent European Writers, Glencoe, Free Press. [ Links ]

PRATT, M.L. (2008 [1992]), Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation, London, Routledge. [ Links ]

PRITCHARD, A., MORGAN, N.J. (2001), “Culture, identity and tourism representation: marketing Cymru or Wales?”. Tourism Management, 22 (2), pp. 167-179. DOI: 10.1016/S0261-51

77(00) 00047-9.

PUTNAM, R.D., CAMPBELL, D.E. (2010), American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us, New York, Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

RIDANPÄÄ, J. (2011), “Pajala as a literary place: in the readings and footsteps of Mikael Niemi”. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 9 (2), pp. 103-117.

ROJEK, C. (1999), “Fatal attractions”. In J. Evans and D. Boswell (eds.), Representing the Nation: A Reader: Histories, Heritage and Museums, London, Routledge, pp. 185-207.

ROYO, S. (2010), “Portugal and Spain in the EU: paths of economic divergence (2000-2007)”. Análise Social, XLV (195), pp. 209-254.

RYAN, C. (2002), “Tourism and cultural proximity: examples from New Zealand”. Annals of Tourism Research, 29 (4), pp. 952-971.

SAID, E. (1978), Orientalism, London, Penguin. [ Links ]

SANTOS, C. (2004), “Framing Portugal”. Annals of Tourism Research, 31 (1), pp. 122-138. DOI: 10.1016/j.annals.2003.08.005.

SANTOS, C., ROZIER-RICH, S. (2009), “Travel writing as a representational space: Doing deviance'”. Tourism, Culture and Communication, 9 (3), pp. 137-150.

SAPELLI, G. (1995), Southern Europe since 1945: Tradition and Modernity in Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece and Turkey, London, Longman. [ Links ]

SOBRAL, J.M. (2004), “O Norte, o Sul, a raça, a nação– representações da identidade nacional portuguesa (séculos XIX-XX)”. Análise Social, XXXIX (171), pp. 255-284.

STYLIANOU-LAMBERT, T. (2012), “Tourists with cameras: reproducing or producing?”.Annals of Tourism Research, 39 (4), pp. 1817-1838.

SUGNET, C. (1991), “Vile bodies, vile places: traveling with Granta”. Transition, 51, pp. 70-85.

THOMAS, W.I., THOMAS, D.S.T. (1928), The Child in America: Behavior Problems and Programs, New York, A.A. Knopf. [ Links ]

TODOROV, T., PORTER, C. (1990), Genres in Discourse, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

TURNER, J.H. (2003), Human Institutions: A Theory of Societal Evolution, Lanham, Md, Rowman & Littlefield.

WALLERSTEIN, I.M. (1974), The Modern World-System, New York, Academic Press. [ Links ]

WANG, Y.A., MORAIS, D.B., BUZINDE, C. (2009), “American media representations of China's traditions and modernity”. Tourism Culture & Communication, 9 (3), pp. 125-135.

WEBER, M. (1975), Roscher and Knies: The Logical Problems of Historical Economics, New York, Free Press. [ Links ]

YAN, G., SANTOS, C.A. (2009), “China, forever”: tourism discourse and self-orientalism”. Annals of Tourism Research, 36 (2), pp. 295-315.

Received at 27-10-2016.

Accepted for publication at 06-06-2017.

[1] Sobral (2004), a rare example, studies representations of Portugal in the 19th and 20th centuries produced by intellectuals, whose audience is arguably more restricted than that of travel writing.

[2] The accession to the the EEC was “a catalyst for the final conversion of the Iberian countries into modern Western-type economies” (Royo, 2010).

[3] The analysis does not consider the intensity of each image, a fact that must be taken into account when interpreting the results. Only a survey on readers could possibly overcome this issue, but it would certainly face the difference between inner perceptions and their externalization, as well the very instability of those perceptions within the instability of the contemporary self (Hall, 1992).

[4] For example, for Said (1978, p. 229), written images of 19th-century Arabs “wipe out any traces of individual's life histories”, while on John Barrow's (1968) 18th-century travel writing Pratt (2008 [1992, p. 62]) finds a homogenization of people into a “collective they which distils down even further into an iconic he”.

[5] Cases are Richard Hewitt's descriptions showing the predominance of affective dimensions over instrumental ones (Parsons, 1949). They are level 1 because the author refers to cases as opposed to an excerpt where he talks of the “intrinsic motivation of the Portuguese worker” (p. 96), a level 3 image.

[6] Examples are the many references made by Camilo José Cela to the demographic or economic situation of the villages he visits.

[7] All the authors being studied use this level of generality, typically with expressions such as “Spain is ” or “the Portuguese are ”.

[8] Postmodernity (and the associated postmodernism) is taken here as encompassing postmaterialistic values reaching beyond material security; reflexivity; conscience of historical relativity; questioning of the place of Western culture; distrust of grand narratives and large explanation systems; emphasis on micro, local, or regional practices, and multiplicity and heterogeneity.

[9] The exact figures are as follows. For Portugal, the top 29.0% themes account for 70.8% of images; each of the remaining themes presents values below 1.9%. For Spain, the corresponding values are 29.6%, 70.2%, and 1.7%. In terms of generality-weighted frequency of themes, values for Portugal are 30.6%, 70.6%, and 1.8%. For Spain, values are 30.1%, 70.4%, and 1.5%.

[10] Arguably, the prejudiced approach of this self-published book could stem in good measure from a failed relationship with a Spanish wife, with whom he moved to Spain. When describing Spanish women, Arencibia holds that “their aggressiveness, moodiness and lack of passion make them unviable candidates for a successful relationship” (p. 245).

[11] His study focuses on a transformation toward a worldwide capitalist economy, starting from 1470.

[12] This cluster consists of the themes (non-specified) agriculture (ambiguous in terms of modernity) and non-mechanized/subsistence agriculture (clearly within pre-modernity) with similar significance.

[13] Results retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/en/data/explorer, July 10th, 2018.