Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.225 Lisboa dez. 2017

ARTIGOS

A tale of two elections: information, motivated reasoning, and the economy in the 2011 and 2015 Portuguese elections

Um conto de duas eleições: informação, raciocínio motivado e a economia nas eleições portuguesas de 2011 e 2015

Pedro C. Magalhães*

*Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Av. Prof. Aníbal Bettencourt, 9 - 1600-189 Lisboa, Portugal. pedro.magalhaes@ics.ulisboa.pt

ABSTRACT

A tale of two elections: information, motivated reasoning, and the economy in the 2011 and 2015 Portuguese elections. Economic performance is thought to be a powerful driver of incumbent electoral performance, and GDP growth and unemployment to be the “big two” factors involved. However, while in the 2011 elections, under a profound economic recession and growing unemployment, the Socialist incumbents lost about one-fourth of the electorate, the center-right coalition experienced losses of similar magnitude in 2015 under a recovering economy and growing employment. Why has this happened? I explore three hypotheses: (1) the economy became a less salient issue in 2015; (2) responsibility for economic outcomes became more blurred in 2015; and (3) national economic evaluations were more contaminated by partisanship and affected by cognitive resources and personal economic experiences in 2015.

Keywords: elections; economic voting; motivated reasoning; austerity policies.

RESUMO

Um conto de duas eleições: informação, raciocínio motivado e a economia nas eleições portuguesas de 2011 e 2015. Pensa-se que o desempenho da economia é um poderoso factor na explicação do desempenho eleitoral dos partidos do governo, e que o crescimento do PIB e o desemprego são os “dois grandes” factores envolvidos. No entanto, enquanto o Partido Socialista perdeu cerca de um quarto dos votos em 2011 sob uma profunda recessão económica e com o desemprego a crescer, a coligação de centro-direita sofreu perdas semelhantes em 2015 sob uma economia em recuperação e com crescimento do emprego. Por que razão sucedeu isto? Exploro três hipóteses: (1) a economia ter-se-á tornado um tema menos saliente para os eleitores em 2015; (2) a responsabilidade pelos resultados da economia ter-se-á tornado mais difusa em 2015; e (3) as avaliações da evolução da economia por parte dos eleitores foram mais contaminadas pela identificação partidária e mais afetadas pelos seus recursos cognitivos e experiências económicas pessoais em 2015.

Palavras-chave: eleições; voto económico; raciocínio motivado; políticas de austeridade.

Introduction

It was the worst of times for the Portuguese Socialists in government in the June 2011 elections. The economy was in its third consecutive quarter of GDP contraction. The unemployment rate, which by 2009 was still below 8%, was now reaching 12%. The budget deficit in 2010 surpassed 11% of GDP, a value of historical proportions. And this in spite of the successive packages of deficit reduction the Socialist government had passed since March 2010, raising direct and indirect taxes, freezing pensions, and reducing social benefits. Just two months before the election, Portugal became the third Eurozone country - after Greece and Ireland - to seek a bailout package from the EU and the IMF in order to maintain its debt obligations, in exchange for extensive policy conditionalities that included further cuts in public sector wages, pensions, benefits, public investment, and health and education expenditures, as well as further tax increases. In the June elections the Socialists got 28% of the vote, a loss of nearly one-fourth of their 2009 electorate and their worst electoral score in more than two decades.

It is hard to say that it was the best of the times for the Portuguese center-right coalition in government as it faced elections in October 2015. After all, since June 2011 the PSD/CDS government had been the one implementing the austerity measures contemplated in the bailout agreement with the EU and the IMF. However, this austerity effort was concentrated in the early years of the legislative term. By end of 2015 the structural deficit actually increased in relation to 2014, in contrast with the previous years. At the time of the election, October 2015, Portugal had enjoyed five consecutive quarters of modest but nevertheless positive GDP growth. The unemployment rate was still high, about 12%, but it had been brought down from the heights of nearly 18% it had reached in the first quarter of 2013. And yet, in the 2015 elections, the two government parties, running together in a pre-election coalition (Portugal à Frente), lost nearly 12 percentage points in vote share in relation to their combined score in the 2011 election, losing about one-fourth of their 2011 electorate, and obtaining their worst combined electoral score in a decade.

It is not easy to reconcile the similarity in the fates of the incumbent parties in these two elections with many of the core arguments in the literature about the relationship between economic performance and incumbent parties' electoral performance. In economic terms, “good times keep parties in office, bad times cast them out” (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, 2000, p. 183), and “the ‘big two' (…) are unemployment and growth” (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, 2013, p. 376). Furthermore, “voters are myopic, with a typical memory of one year” (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, 2013, p. 378). If this is true, a question becomes paramount: why did the incumbent parties perform so badly in both elections with such different economic contexts? This is the simple question investigated by this research note.

I explore three of several possible answers. The first is the possibility that in 2015 the economy had become a less important concern in people's minds, rendering evaluations and perceptions of national economic conditions less relevant for the vote function, at least in comparison with 2011. The second is the possibility that, for better or for worse, the center-right parties in government were seen by voters as less responsible for the country's economic situation in 2015 than the Socialists were for the economic crisis in 2011. Finally, I explore the possibility that regardless of the relevance of perceptions of the economic situation for vote choices and of the responsibility awarded to the government for that situation, voters' assessments of the economy were more influenced in 2015 by their political predispositions, their level of knowledge, and their personal economic experiences than in 2011. In other words, that the endogeneity of economic perceptions was more pronounced following the period of modest economic growth in 2015 than following the period of economic crisis in 2011. The data I have been able to amass so far favors this last interpretation. In the conclusion, some potential implications of this are discussed.

The salience of economic concerns

To restate: why did the incumbent parties perform so badly in both elections with such different economic contexts? One explanation for this may simply be that the state of the economy competes with other issues in the definition of what the elections are about. Regardless of whether we assume voters to be primarily retrospective or prospective, government's handling of the economy is not the single imaginable concern of voters. Corruption, crime, the environment, education, foreign policy, immigration, and many other issues may be downplayed or reinforced in importance as a result of objective conditions and political agenda-setting and framing, especially as a result of the efforts on the part of political actors who “own” those issues (RePass, 1971). This is thought to be highly consequential for the way voters evaluate incumbents: “any issue singled out as personally most important plays a substantially greater role for those who so view it than it does for others” (Rabinowitz, Prothro, and Jacoby, 1982, p. 57). Furthermore, and rather importantly for our case, several studies have shown that the salience of the economy as an issue and the reliance of voters on economic factors to base their vote choices seems to increase during economic downturns, because such downturns tend to generate greater media and public attention (Harrington, 1989; Soroka, 2006). In a recent comparative study, Singer summarizes these findings by showing that “economic issues gain widespread importance as the economic climate worsens” (Singer, 2011, p. 301), and that “voters who said that the economy was important place greater weight on economic outcomes [when voting] than the rest of the citizenry” (Singer, 2011, p. 297). This suggests that, for Portuguese voters, the economy may simply have become less important an issue in 2015 than it had been in 2011.

Our ability to test all implications of these ideas is limited by the fact that we are dealing with just two cases, and are furthermore unable to look at this explicitly at the individual level. The 2011 and 2015 Portuguese post-election surveys are not exactly alike, differing in one crucial aspect. In 2011, the survey contained an open-ended question about “the most important issue, for you personally, in this election.” Following recoding, only ten issues received mention by more than 1 percent of respondents. The economy - expressed in terms like “the economic situation”, “the economic crisis”, and “unemployment” - was mentioned directly by 23% of respondents and was, by far, the most mentioned topic. However, in 2015, there is no such question on the basis of which to make an aggregate-level comparison, and much less to test whether different individuals voted differently on the basis of their issue priorities.

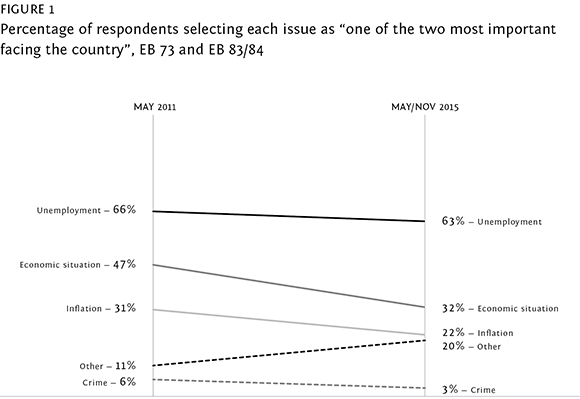

However, other data sources allow us to at least evaluate the plausibility of the idea that by 2015 the economy had become less salient an issue for voters than in 2011. The Eurobarometer regularly poses a question about “the two most important issues facing (our country) at the moment?” The slope graph in Figure 1 shows the proportion of respondents who selected the three most mentioned issues in the Eurobarometer waves of May 2011 (one month before the election) and on the average of the May 2015/November 2015 surveys (the election was in October). Furthermore, I show the similar trend pertaining to the most mentioned issue besides those “big three” (“Other”) and also for the most mentioned non-economic issue (“Crime”).

First, note that “unemployment,” “the economic situation,” and “inflation/cost of living” were, in both periods, the three issues most mentioned as “most important.” To be sure, the percentage of respondents who were concerned with the economic situation and with inflation seems to have fallen from 2011 to 2015, while the fourth most mentioned issue (“Other”) picked up steam from one period to the next. However, there is no substantial decline for the most mentioned issue (“unemployment”). Furthermore, note that while in May 2011 the fourth most selected issue was “taxes,” in all subsequent surveys until 2015 that issue was “government debt/budget deficit,” which is obviously connected with the management of the economy by the government. Finally, of all issues included in the EB surveys' questionnaire, the one that is most mentioned while being clearly decoupled from the economy is “crime.” As we can see, in 2015 mentions of “crime” had become even fewer than they were in 2011. In other words, the evidence that the state of the economy and economic developments ceased to be paramount in the minds of Portuguese voters in 2015 is far from clear on the basis of these data.

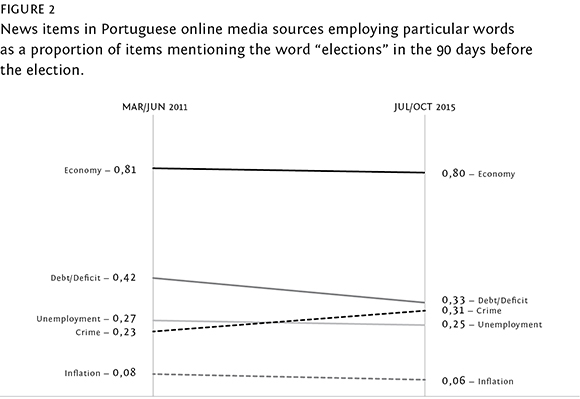

Another way of capturing the salience of different issues is to look at the media. Figure 2, another slope graph, shows the number of news items in the Portuguese media containing particular words or expressions as a proportion of the number of news items containing the word “elections,” in the 90 days before the date of each election. I used an API from the News web service developed by SAPO Labs, containing the texts of all online news items issued by all major Portuguese news sources (including all major newspapers and TV and radio stations, as well as online-only news websites) and by the Portuguese news agency, Lusa.

In the 90 days before the 2011 election, 18,881 news items employed the word “economy” (“economia”) in their title or in the body of the text, representing 0.81 of all items containing the word “elections” (“eleições”) in the same period. In the 90 days before the 2015 election, that proportion was basically the same (0.80). Mentions of “public debt” (“dívida publica”) or “deficit” (“défice”) did fall in comparison to 2011, but mentions of “unemployment” (“desemprego”) or “inflation”/“cost of living” (“inflação”/“custo de vida”) remained mostly stable, while mentions of “crime”/“criminality” (“crime”/“criminalidade”) increased, but still below those of the two most mentioned economic topics. Thus, in general, using an admittedly rough measure of the presence of these themes in news items, and in this case with the exception of “public debt”/“deficit,” we see again little evidence that economic issues had became less important in the news agenda during the campaign in 2015 in comparison to 2011.

A final piece of evidence concerning the salience of the economy for voting is a more direct one, and concerns the relationship between voters' retrospective evaluation of the state of the economy and their voting choices. If the economy had become a less salient issue for voters, one should expect evaluations of the economy to play a smaller role in the vote function in 2015 in comparison with 2011, which in turn might account for the inability of the incumbent center-right parties to capitalize on the economic improvement of 2014-2015. In both post-election surveys conducted in 2011 and 2015, respondents were asked about whether, in the last 12 months, the state of the economy had become “much worse,” “somewhat worse”, “stayed the same,” “somewhat better,” or “much better,” i. e., the basic retrospective sociotropic question.

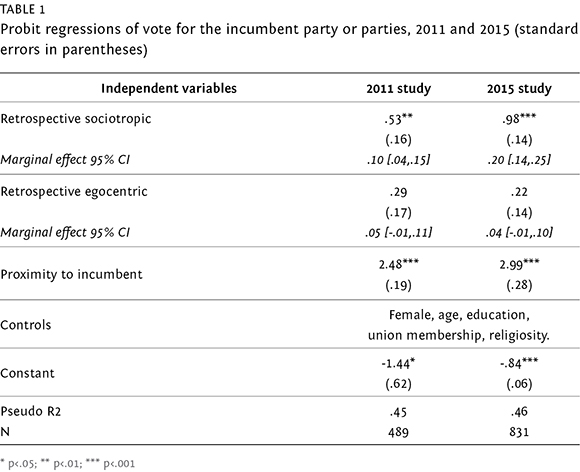

Table 1 shows the result of probit regression analyses of the vote for the incumbent party in 2011 (the Socialist Party) and 2015 (the PSD/CDS coalition) vs. the vote for any of the opposition parties. All independent variables are either dummy variables (Female, Union membership, Proximity to incumbent party) or have been standardized by being divided by two standard deviations, rendering coefficients roughly comparable with those pertaining to the dummy variables.

From the results we see no evidence that in 2015 economic evaluations were weaker correlates of the vote for the incumbent than in 2011. In fact, the results point in the opposite direction. The size of the coefficient for retrospective sociotropic evaluations in 2011 is about half of the size in 2015. Moving from the minimum to the maximum retrospective evaluation of the economy in 2011 - while keeping the remaining variables at their mean values - is estimated to increase the probability of voting for the incumbent party by about 10 percentage points. That increase, for 2015, is estimated to be of about 20 percentage points, with the 95% confidence intervals of this and the previous marginal effect barely overlapping. Other results point to a predictably very large effect of partisanship and to the negligible effect of egocentric evaluations once both sociotropic evaluations and partisanship are taken into account - both findings being widely reported in the literature. In any case, the main message is relatively simple. The decreasing salience of the economy as a campaign issue, and the possible decrease in importance of economic evaluations as determinants of the vote for the incumbent party, do not seem, on the basis of these data, particularly promising explanations for the puzzle being addressed.

Responsibility for the economy

Another reason why the incumbent parties in 2015 may have failed to benefit from improvements in the objective economy could be related to “clarity of responsibility.” Governments control the economy to different extents. Lower control makes it more difficult for voters to blame or reward governments for past performance (Powell and Whitten, 1993) or leads them to give more weight to exogenous factors when using past performance to select a new incumbent (Duch and Stevenson, 2008). Variables that shape control are thought to be institutional features that increase opposition influence in national policymaking (Powell and Whitten, 1993; Duch and Stevenson, 2008, pp. 277-286) or disperse power across multiple levels of government within a country (Anderson, 2006), as well and levels of economic interdependence that diminish elected policy makers' control over the economy (Hellwig, 2001; Hellwig and Samuels, 2007). Furthermore, several studies have shown that even under relatively stable structural conditions, messages and framing on the part of political elites and the media can operate important effects on the extent to which people perceive governments to be in control of the economy and, thus, assign responsibility to incumbents for economic outcomes (Hellwig and Coffey, 2011; Magalhães, 2014).

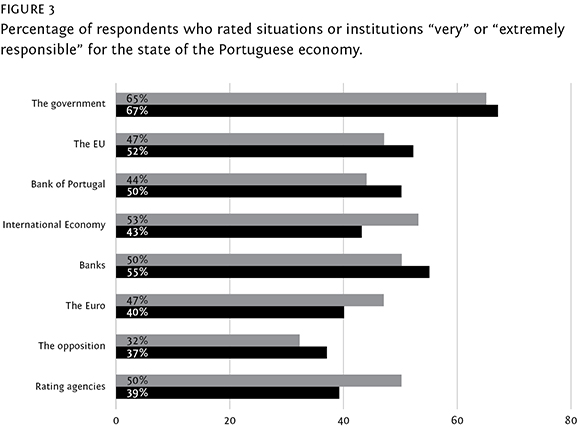

Although I obviously lack the number of cases that would allow me to explore variation in “clarity of responsibility” across elections, the 2011 and 2015 post-election surveys allow us to gain some insight in this respect. Following the questions on the state of the economy, the two post-election surveys asked respondents “To what extent do you think the following institutions and situations are responsible for the state of the economy in recent years?”. Following that introduction, respondents were asked to rate a list of agents and factors as being “not at all responsible,” “with little responsibility,” “somewhat responsible,” “very responsible,” and “extremely responsible”. Figure 3 shows the percentage of respondents that, in both surveys, rated each factor as “very” or “extremely” responsible.

There are some small fluctuations from 2011 to 2015. In particular, in comparison with 2011, fewer respondents thought in 2015 that rating agencies, the international economy, and the Euro were “very” or “extremely” responsible for the state of the Portuguese economy. In contrast, the European Union, the Bank of Portugal, banks in general, and the opposition parties were seen as responsible by more respondents than in 2011. Having said that, these differences between the two surveys are relatively small, and the same basic structure is maintained: while the government stands out as the factor most people see as responsible for the economic situation, many voters also assign strong responsibility for the economy to many agents and forces.

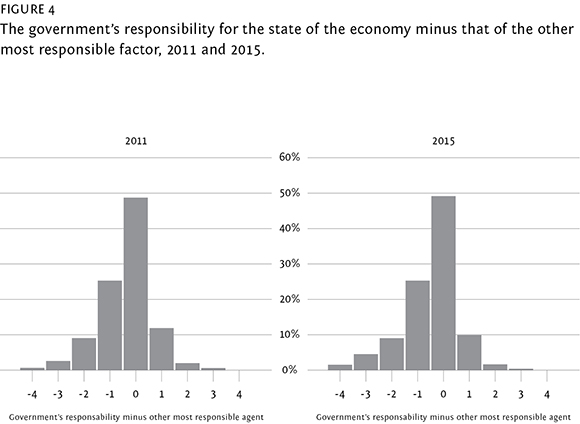

Fuller use of the survey information available on this topic can be made. Responsibility for the economy for each of those factors is coded from 1 to 5, from “not at all” to “extremely” responsible. Thus, a new variable was created in which the maximum value awarded to each factor other than the government was subtracted from the value awarded to the government. Positive values mean that the government was seen as more responsible for the state of the economy than any other factor. Negative values mean that at least one of those factors is held more responsible for the economy than the government. Figure 4 shows how respondents were distributed along the values of this variable for both surveys.

The two histograms are remarkably similar. The most frequent value is zero, meaning that most respondents attributed equal responsibility for the economy to the government and to at least one of the other agents or factors. Conversely, in 2011 and 2015, respectively, only about 12% and 14% of respondents thought the government was more responsible than any other factor for the state of the economy. The picture that emerges, therefore, is one in which government's responsibility for the economy is considerably blurred for many voters, in both 2011 and 2015. Early on, I speculated that one of the reasons why the center-right coalition failed to capitalize on the positive economic performance in the year and a half before the 2015 election was that it was held less accountable for economic performance than the Socialists were in 2011. However, in general, we end up seeing no difference in the overall distribution of these assignments of economic responsibility to the government from one election to the next.

It is not entirely surprising that few changes took place between 2011 and 2015 in this respect. None of the structural features thought to be crucial witnessed any major change in this period. None of the incumbents was a single-party majority government. Instead, while the Socialists ruled alone with a minority government, PSD and CDS ruled with a majority coalition. By 2015 the country remained as much a centralized state - one of the most centralized in Europe - as it had been in 2011. And Portugal obviously remained as a relatively small and open economy in those years, with its economic policies constrained by Eurozone membership and all that it entails.

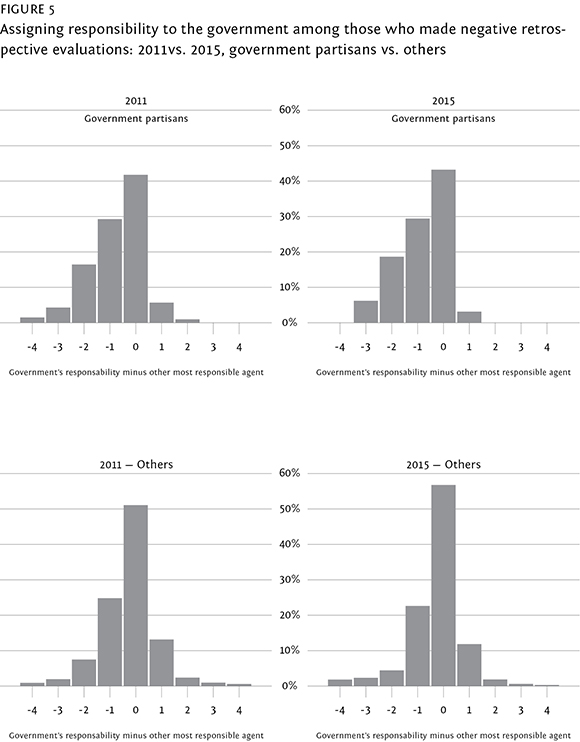

Furthermore, regardless of the contextual aspects, institutional and economic, that might conceivably affect the assignment of responsibility to the government, there is increasing evidence that these judgments of responsibility are shaped by relatively stable predispositions of voters. As Bisgaard (2015) shows, even when they converge on a consensual negative evaluation of economic conditions, individuals construct, with the help of partisan cues and media spin, their own accounts about who is responsible for that negative outcome, an account that tends to be consistent with their partisan identities. Portugal was no different in this regard. Figure 5 shows, for 2011 and 2015, how, among those who made a negative retrospective evaluation of the economy, government partisans and other voters assigned responsibility for the economy to the government, using the measure described above. Among partisans of the incumbent party, PS in 2011 and PSD/CDS in 2015, the distribution is clearly more skewed to the left, meaning that more voters assigned greater responsibility for the (negative) economy to any factor other than the action of the government. For the remaining voters who evaluated the economy negatively, the exoneration of the government was much less pronounced. The patterns are very similar in both elections.

The conditional endogeneity of economic evaluations

So why was the right punished by an improving economy as much as the Socialists were punished by a massive economic crisis? A third possibility is that, although several objective indicators pertaining to the Portuguese economy were indeed improving before the 2015 elections, other factors interfered with the perception of such improvements. In contrast to the two preceding speculations, this does not imply that the economy was less important an issue in the political agenda in 2015 or that economic perceptions were more weakly correlated with the vote (the “salience” hypothesis). Nor does it require that the government was seen to be less responsible for economic conditions (the “responsibility” hypothesis) in 2015. Instead, it implies that in 2015 voters' views of the state of the economy may have been less a function of objective macroeconomics than in 2011, and instead more a function of their own predispositions, knowledge, and personal economic experiences. In other words, it implies that economic perceptions may have been more endogenous in 2015 than in 2011.

In the last decade and a half, an important body of research has shown that, as Anderson puts it, “citizens are likely to systematically misjudge the state of the economy even when it is presented to them on a silver platter” (Anderson, 2007). That misjudgment is not random. When seeking information, “directional goals”, which motivate individuals to “apply their reasoning powers in defense of prior, specific conclusion” (Taber and Lodge, 2006, p. 756), are often paramount. The result is that citizens' understanding of the political, social, and economic contexts is pervaded by partisan motivated reasoning that serves those directional goals (Bartels, 2002). One implication of this is that the impact of economic perceptions on the vote is likely to be overestimated if one does not take into account how those perceptions are themselves conditioned by partisanship and other aspects of partisan approval in the first place (see Evans and Andersen, 2006 and Evans and Pickup, 2010, among many). On the other hand, even when motivated by “accuracy goals,” individuals are affected by the information they have accumulated on the basis of their personal experience and constrained by their ability to seek further information. Thus, it is not surprising that “how people view economic performance is shaped by their political predispositions, personal financial experiences, socioeconomic situation, and level of understanding about the political economy” (Duch, Palmer and Anderson, 2000, p. 649).

Having said that, the extent to which economic perceptions become endogenous is likely to be contingent upon different factors. There are two main arguments, one of a more general nature, and another more specific to the economic and political context experience by a country like Portugal from 2011 to 2015, that may explain the extent to which economic perceptions become endogenous. First, economic performance itself may be relevant in this respect. Evans and Andersen (2006, p.195) suggested early on that serious economic downturns “would elicit shared and reasonably perceptive responses that are not powerfully affected by political conditioning.” As Dickerson (2015, p. 2) puts it, “voters are more heavily exposed to negative economic information during economic downturns, which may conflict with their prior political attitudes - attitudes that subsequently become less useful as cognitive shortcuts for processing economic information”. In contrast, under conditions of relative stability, “partisan ‘contamination' of voters' understanding of economic performance is much more likely” (Evans and Andersen, 2006, p. 195). Chzhen, Evans, and Pickup (2014), using panel surveys covering two different periods, one of moderate economic growth (1997-2001) and another of economic crisis (2005-2010), show that in the former the positive correlation between economic perceptions and incumbent approval should be seen as a consequence of the fact that people who approve of the incumbent develop a better evaluation of the economy. In contrast, during the period of economic crisis, economic perceptions do seem to have an exogenous effect on incumbent approval. They conclude that “when voters perceive the economy as a salient issue and react to clearer economic signals, they adjust their preferences accordingly”, and thus that “during economic crises, the role of economic perceptions as sources of electoral accountability (…) is to some degree validated” (Chzen, Evans, and Pickup, 2014, p. 308). However, under conditions of economic stability or modest growth, economic perceptions are more determined by partisan preferences. Similarly, Dickerson, also using panel data, finds that economic perceptions had a stronger exogenous effect on presidential approval in the US during the Great Recession than in other periods (Dickerson, 2015).

The second argument as to why economic perceptions may have been more endogenous in 2015 than in 2011 has to do with the specific political and economic circumstances that preceded the former election. Examining the popular reactions to the Great Recession and summarizing the contributions to their edited volume, Bermeo and Bartels note that such reactions were often “associated less with the direct economic repercussions of the crisis than with the government initiatives to cope with those repercussions” (Bermeo and Bartels, 2014, p. 4). Austerity provides “a much more salient focal point for mobilization than the release of statistics on economic growth and unemployment,” and serves as a “trigger that enables ordinary people to link economic hardship directly to the action of incumbent political elites” (Bermeo and Bartels, 2014, p. 29). Furthermore, as Achen and Bartels argue (2016), if it is generally true that voters' “factual judgments are likely to be significantly and pervasively influenced by their partisan dispositions” (Achen and Bartels, 2016, p. 284), this “contamination” can be further strengthened in reaction to particular political developments: “when political events make a particular identity salient or threatened, powerful psychological forces can be evoked, with effects that go well beyond the impact of the issues involved” (Achen and Bartels, 2016, p. 267). In other words, the austerity policies pursued in the sequence of the Portuguese bailout - whose rejection by the Portuguese electorate increased continuously since 2011 (Moury and Freire, 2013) - their enormous salience and contentiousness, may have constituted triggers that activated among voters a stronger connection between their personal economic circumstances and their partisan identities and their views of the “objective” economy.[1]

A PATH MODEL

Unfortunately, we lack panel survey data for the period preceding either the 2011 or the 2015 Portuguese elections, which would allow us to examine the question of endogeneity of economic perceptions more fully. However, a somewhat better examination can be made than by just modeling the vote for the incumbent as the combined direct and unmediated effect of economic perceptions, partisanship, and other factors, as I did in the analysis whose results are presented in Table 1. Instead, I propose and estimate a path model for the vote choice in both elections, using structural equation modeling.

In the analysis whose results were presented in Table 1, we could see the relationship between the vote and a list of variables assumed, for theoretical reasons, to be predictive of that vote - such as retrospective economic evaluations, partisanship, etc. The multiple regression - in that case, a probit regression - allowed the estimation of the independent contribution of each predictor to the determination of the dependent variable, i. e., taking into account the collinearity patterns among the predictors. However, path analysis allows us to also examine the structure of the relationships between the predictor variables, and thus of the plausibility of a particular causal path among the predictors and toward the criterion variable. In other words, path analysis contemplates not only direct effects, in which one predictor affects the response variable, but also indirect effects, in which one predictor affects another predictor, which in turn affects the response variable. Obviously, the use of “causal” language is allusive: path analyses do not establish causality, but only reveal the extent to which hypothesized causal paths fit the observational data.

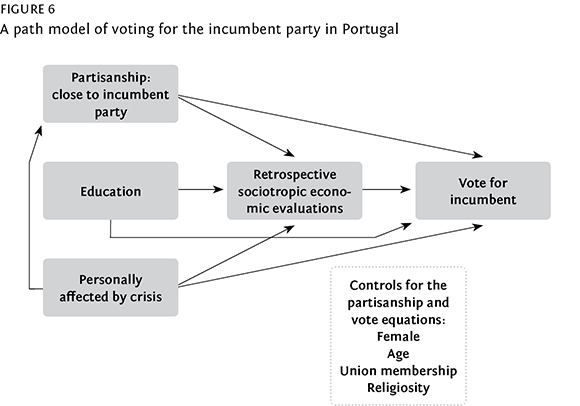

Figure 6 presents our proposed path model. Vote for the incumbent party vs. opposition (a dichotomous variable with 1 representing vote for incumbent) is modeled as a function of partisanship, retrospective sociotropic evaluations of the economy, and several control variables (gender, education, age, union membership, education, and religiosity). The controls are not detailed in the diagram, with the exception of education, for reasons that will be explained later. Furthermore, an additional variable in the vote equation aims to capture the retrospective personal economic situation of the respondent. However, instead of relying on the conventional retrospective egocentric or pocketbook question -“would you say that your personal economic situation has gotten worse, better, or stayed the same?” - I employ a different strategy less likely to generate answers contaminated by voters' prior partisan predispositions. In both surveys, respondents were asked a factual question: if, at any point since the last election, they had “lost their job,” “had their salary or pension cut or frozen,” or moved from “full time to part time” work, i. e., all aspects that reflect the potential impact of the economic crisis and the austerity measures taken by the Socialist, first, and the center-right government, later.

Another implication of this path model is that I assume neither partisanship nor economic evaluations to be exogenous variables. Instead, I assume that evaluations of the national economy to be affected by partisanship, as a result of partisan motivated reasoning, and also by individuals' cognitive resources and personal economic experiences. In other words, I expect economic perceptions to be affected by education and the extent to which individuals were personally affected by the crisis. For partisanship, the basic expectation is that incumbent partisans will have more positive evaluations of the economy. I also expect that people who were more personally affected by the crisis should make a more negative evaluation of the evolution of the national economy. Finally, I expect people with higher levels of education to be more informed of the actual changes in the national economy, controlling for their partisanship, how they were personally affected and regardless of how education may affect the vote and partisanship in the first place. Therefore, education should have a negative sign in 2011 and a positive sign in 2015. Partisanship is also treated as an endogenous variable, determined not only by the set of control variables (including education) and also by the objective economic experiences of respondents during the term of office of the incumbent. Finally, and most importantly, if Evans and Andersen's (2006) speculation is correct and taking into account the findings by Chzhen, Evans, and Pickup (2014) and Dickerson (2015), economic evaluations around the election that followed a pronounced economic downturn (2011) should be less contaminated by all of these factors than in 2015.

RESULTS

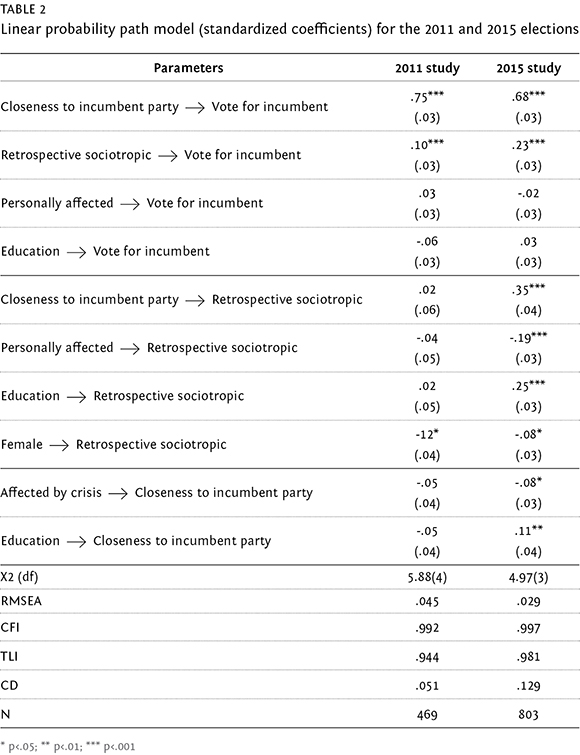

Path models are a particular case of structural equation models, but containing only observed variables and one indicator per variable. I first estimated the model in Figure 6 for both the 2011 and 2015 elections, using linear probability models, i. e., treating all variables as continuous, in order to be able to obtain fit statistics (later I test a more appropriate specification using probit and ordered probit). These models already showed a reasonably good fit but also that, in both cases, after estimating modification indices, fit could be further improved by including Female in the equation for national economic evaluations. Table 2 thus shows the results of the final linear probability path model for both elections. Parameters for the control variables are not shown.

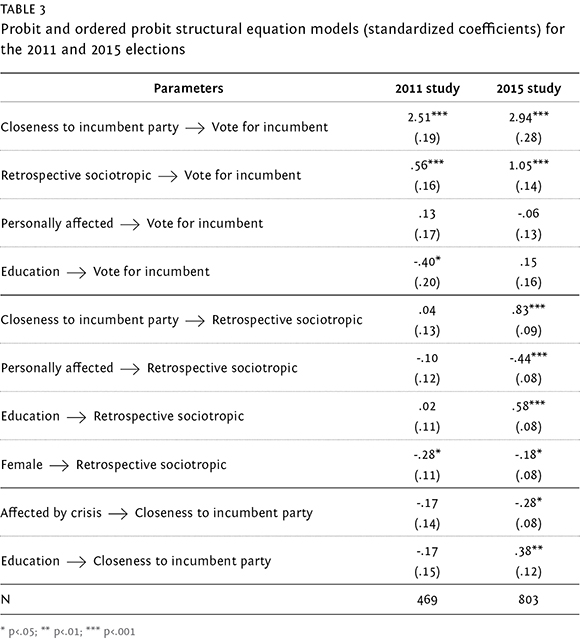

The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) measures of model fit, in all cases indicate a good model fit. The coefficient of determination (CD) is tantamount to an R-squared, indicating that variance explained is lower in 2011 than in 2015. In the vote equation, in the first section of the table, we can see the result we have already observed: economic evaluations have a significant positive relationship with the vote, stronger in 2015 than in 2011, and personal economic circumstances have no direct effects on vote choice.

However, the results for the economic evaluations equation, in the second part of the table, are completely different in the two elections. In 2015 economic evaluations were driven by partisanship, the extent to which the respondent was personally affected by the crisis, and education (with more educated respondents making a better evaluation of the economy). In 2011 none of these variables has a coefficient that is statistically different from zero. In other words, while economic evaluations were strongly predictive of the vote for the incumbent in 2015, such evaluations were clearly endogenous. The same cannot be said for 2011, on the basis of this analysis.

Another interesting aspect of the results pertains to the effect of the respondent's personal economic situation, captured here in terms of how his or her income and job security was affected in recent years. The standard account in the economic voting literature is that “pocketbook effects are weak to nonexistent” (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, 2013, p. 371), and that much could be concluded by looking at the results either in Table 1 or the vote equation in the first section of Table 3. However, a more complete analysis of the 2015 elections suggest that, even employing a measure of personal economic circumstances more likely to be exogenous than the traditional “egocentric retrospective” measure, individual economic difficulties do matter for the vote. But they seem to do so indirectly: both by decreasing the probability that one has remained a partisan of the incumbent party and, especially, by promoting a more negative evaluation of national economic conditions. This only occurred, however, in the election where, objectively, those conditions were more favorable. Under the economic crisis context of 2011, no such effects emerge.

Table 3 shows the results after I use probit for the vote choice and partisanship equations, and ordered probit for the economic evaluations equation, using a generalized structural equation model. They do not differ in any major way from those obtained in the linear probability structural equation model.

The implications are simple. Although the economy was doing better in 2015, voters' perception of the state of economy, consequential as it was for the vote choice, seems to have been much more contaminated by causally prior aspects than in 2011. Those voters who were not partisans of any of the government parties were not only less likely to vote for them - as in 2011 - but also less likely to form a positive evaluation of the economy in the first place. Less educated voters were also less likely to have perceived any improvements in the national economy, and so were those who had been personally affected in terms of their income and job security during the preceding term of office of the legislative term. In 2011 no such indirect effects of partisanship, education, or personal economic circumstances are visible.

Discussion

Why did voters punish the government parties in a context of economic crisis in 2011 but also under an improving economy in 2015? I discussed three possible answers to that question. The first was the possibility that the economy had become a less salient issue than in 2015 than it was in 2011. However, we saw little evidence of that being the case, and even showed a stronger relationship between economic perceptions and the vote in 2015. The second was the possibility that voters failed to attribute responsibility to the government for the economic situation in 2015. We indeed saw that many voters attributed such responsibility to actors and forces beyond the government's control, but also that, from this point of view, 2015 was no different from 2011. Finally, I discussed the possibility that economic perceptions, regardless of the strength of their relationship with the vote, were in and of themselves shaped by different forces in 2011 and 2015. And this seems indeed to be the case.

Why? With just two different elections analyzed with cross-sectional survey data, with all the limitations that implies, it is impossible to be categorical. However, two possible answers emerge. The first is that economic perceptions are generally more likely to be exogenous in contexts where objective economic performance is negative (Evans and Andersen, 2006). This would explain why, unlike what happened in 2011, the period of real but modest economic growth that preceded the 2015 elections led to divergences around the perceived state of the economy being structured not only on a partisan basis, but also in terms of cognitive resources and personal economic experiences. Furthermore, it would help to account for the often replicated finding (Mueller, 1970; Nannestad and Paldam, 1997; Bélanger and Meguid, 2008; Singer, 2011) that economic effects on the vote are asymmetric, i.e, that incumbents are more harmed by negative economic developments than they are benefitted by positive ones.

The second argument, more specific to the context of Portugal and other countries after 2011, is that the austerity policies pursued with greater public salience and vigor during part of the term that led to the 2015 elections were themselves responsible for activating the personal economic hardships and partisan identities of voters as lenses through which to view the national “objective” economy (Bermeo and Bartels, 2014; Achen and Bartels, 2016), thus dampening the effect of recovery. This would help to account for why, in other countries also experiencing economic improvements in post-austerity contexts - such as Spain in 2015 or Ireland in 2016 - incumbent parties nonetheless experienced important electoral losses (16 points for PP in Spain, 22 points for FG and Labor in Ireland. Furthermore, this should also lead us to reconsider the circumstances under which traditional “retrospective sociotropic” accounts of economic voting prevail and those under which resilient personal economic hardship (Marsh and McElroy, 2016, p. 170), labor market marginalization (Fernández-Albertos, 2015), and other enduring legacies of crisis and austerity prevent the incumbent parties from fully reaping the benefits of objective economic recovery at the national level.

REFERENCES

ACHEN, C. H., and BARTELS, L. M. (2016), Democracy for Realists: Why Elections do not Produce Responsive Government, Princeton, Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

ANDERSON, C. D. (2006), “Economic voting and multilevel governance: a comparative individual-level analysis”. American Journal of Political Science, 50 (2), pp. 449-463. [ Links ]

ANDERSON, C. J. (2007), “The end of economic voting? Contingency dilemmas and the limits of democratic accountability”. Annual Review of Political Science, 10, pp. 271-296. [ Links ]

BARTELS, L. M. (2002), “Beyond the running tally: partisan bias in political perceptions”. Political Behavior, 24 (2), pp. 117-150. [ Links ]

BÉLANGER, É. and MEGUID, B. M. (2008), “Issue salience, issue ownership, and issue-based vote choice”. Electoral Studies, 27 (3), pp. 477-491. [ Links ]

BERMEO, N. and BARTELS, L. M. (2014), “Mass politics in tough times”. In L. M. Bartels and N. Bermeo (eds.), Mass Politics in Tough Times, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 1-39. [ Links ]

BISGAARD, M. (2015), “Bias will find a way: economic perceptions, attributions of blame, and partisan-motivated reasoning during crisis”. The Journal of Politics, 77 (3), pp. 849-860. [ Links ]

CHZHEN, K., EVANS, G., and PICKUP, M. (2014), “When do economic perceptions matter for party approval?”. Political Behavior, 36 (2), pp. 291-313. [ Links ]

DICKERSON, B. (2015), “Economic perceptions, presidential approval, and causality. The moderating role of the economic context”. American Politics Research, 44 (6), pp. 1037-1065. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X15600787 [ Links ]

DUCH, R. M., and STEVENSON, R. T. (2008), The Economic Vote: How Political and Economic Institutions Condition Election Results, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

DUCH, R. M., PALMER, H. D., and ANDERSON, C. J. (2000), “Heterogeneity in perceptions of national economic conditions”. American Journal of Political Science, 44 (4), pp. 635-652. [ Links ]

EVANS, G., and ANDERSEN, R. (2006), “The political conditioning of economic perceptions”. Journal of Politics, 68 (1), pp. 194-207. [ Links ]

EVANS, G. and PICKUP, M. (2010), “Reversing the causal arrow: the political conditioning of economic perceptions in the 2000-2004 US presidential election cycle”. The Journal of Politics, 72 (4), pp. 1236-1251. [ Links ]

FERNÁNDEZ-ALBERTOS, J. (2015), Los votantes de Podemos, Madrid, Catarata. [ Links ]

HARRINGTON, D. E. (1989), “Economic news on television: the determinants of coverage”. Public Opinion Quarterly, 53 (1), pp. 17-40. https://doi.org/10.1086/269139 [ Links ]

HELLWIG, T. T. (2001), “Interdependence, government constraints, and economic voting”. Journal of Politics, 63 (4), pp. 1141-1162. [ Links ]

HELLWIG, T. and COFFEY, E. (2011), “Public opinion, party messages, and responsibility for the financial crisis in Britain”. Electoral Studies, 30 (3), pp. 417-426. [ Links ]

HELLWIG, T., and SAMUELS, D. (2007), “Voting in open economies. The electoral consequences of globalization. Comparative Political Studies, 40 (3), pp. 283-306. [ Links ]

LEWIS-BECK, M. S. and STEGMAIER, M. (2000), “Economic determinants of electoral outcomes”. Annual Review of Political Science, 3 (1), pp. 183-219. [ Links ]

LEWIS-BECK, M. S. and STEGMAIER, M. (2013), “The VP-function revisited: a survey of the literature on vote and popularity functions after over 40 years”. Public Choice, 157 (3-4), pp. 367-385. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, P. C. (2014), “The elections of the great recession in Portugal: performance voting under a blurred responsibility for the economy”. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties, 24 (2), pp.180-202. [ Links ]

MARSH, M. and MCELROY, G. (2016), “Voting "SpellE", Londres, Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 159-184. [ Links ]

MOURY, C. and FREIRE, A. (2013), “Austerity policies and politics: the case of Portugal”. Pôle Sud, 2, pp. 35-56. [ Links ]

MUELLER, J. E. (1970), “Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson”. American Journal of Political Science, 64 (1), pp. 18-34. [ Links ]

NANNESTAD, P. and PALDAM, M. (1997), “The grievance asymmetry revisited: a micro study of economic voting in Denmark, 1986-1992”. European Journal of Political Economy, 13 (1), pp. 81-99. [ Links ]

POWELL JR, G. B. and WHITTEN, G. D. (1993), “A cross-national analysis of economic voting: taking account of the political context”. American Journal of Political Science, 37 (2), pp. 391-414. [ Links ]

RABINOWITZ, G., PROTHRO, J. W., and JACOBY, W. (1982), “Salience as a factor in the impact of issues on candidate evaluation”. The Journal of Politics, 44 (1), pp. 41-63. [ Links ]

REPASS, D. E. (1971), “Issue salience and party choice”. American Political Science Review, 65 (2), pp. 389-400. [ Links ]

SINGER, M. M. (2011), “Who says “It's the Economy”? Cross-national and cross-individual variation in the salience of economic performance”. Comparative Political Studies, 44 (3), pp. 284-312. [ Links ]

SOROKA, S. N. (2006), “Good news and bad news: asymmetric responses to economic information”. Journal of Politics, 68 (2), pp. 372-385. [ Links ]

TABER, C. S., and LODGE, M. (2006), “Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs”. American Journal of Political Science, 50 (3), pp. 755-769. [ Links ]

Received at 02-03-2017. Accepted for publication 20-09-2017.

[1] I thank one of the anonymous reviewers for calling attention to these points.