Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.221 Lisboa dez. 2016

ARTIGO

The Portuguese media system and the normative roles of the media: a comparative view

O sistema mediático português e os papéis normativos dos media em perspetiva comparativa

José Santa-Pereira*

Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa, Avenida Prof. An;íbal de Bettencourt, 9 1600-189 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: jose.pereira@ics.ulisboa.pt

ABSTRACT

This article analyzes the structure of the Portuguese media system and perceptions regarding the performance of its normative roles from a comparative perspective. This analysis allows us to determine if the patterns identified in the Portuguese case follow a common trend found in other western democracies as well as the structural constraints associated with performance differences. The empirical data analyzed show that the Portuguese media system is characterized by structural patterns and normative roles identical to those of other polarized pluralist systems, and that in Europe media performances depend greatly on the levels of journalist professionalization.

KEYWORDS: media systems; Portugal; quality of democracy; comparative study.

RESUMO

O presente artigo analisa a estrutura do sistema de media português e as perceções a respeito do desempenho dos seus papéis normativos em perspetiva comparativa. A análise comparativa permite perceber se os padrões identificados para o caso português seguem uma tendência comum noutras democracias ocidentais, e quais são os constrangimentos de natureza estrutural que estão associados a diferenças em termos de desempenho. Os dados empíricos analisados mostram que o sistema mediático português é marcado por padrões estruturais e de desempenho dos seus papéis normativos idênticos ao de outros sistemas pluralistas polarizados, e que, na Europa, o desempenho dos media depende em grande medida dos níveis de profissionalização dos jornalistas.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: sistemas de media; Portugal; qualidade da democracia; estudo comparativo.

INTRODUCTION

The debate on the relationship between the media, the political sphere, and the workings of democratic societies is almost as old as mass media itself (Lundberg, 1926). With the exception of the lull brought about by the minimal effects paradigm (Lazarsfeld, Berelson, and Gaudet, 1944), the media have been perceived as relevant instruments or agents, in the sense that they can affect the political attitudes and behaviors of the citizenry, interfering therefore in the democratic process. There remain, nevertheless, different normative stances on the positive or negative nature of that impact.

On the one hand, several studies underscore the positive role of the media. The mass media are the main source of political information for most citizens since the political sphere is usually well out of their reach. Political issues may be complex and far from the daily experience of most people, and the media therefore do their share to present the citizens with a better understanding of the political sphere, raising their levels of awareness and political sophistication. There are several empirical works about the positive influence of media exposure on the citizens level of political knowledge (Zhao and Chaffee, 1995; Chaffee and Kanihan, 1997; Eveland and Scheufele, 2000; de Vreese and Boomgaarden, 2006; Santana-Pereira, 2016; and several others).

On the other hand, a number of authors present negative and pessimistic views about the role and effects of the media. The proponents of terms such as video malaise (Robinson, 1976) or bowling alone (Putnam, 1995) underline the negative influence of media overexposure, namely the decrease of trust in institutions, a reduced perception of political efficacy, and the erosion of social capital. The media are charged with various other sins, such as promoting ignorance or the misunderstanding of important issues due to an excessively fast information flux, homogenizing society, creating the idea of a cruel world, bringing about a decrease in political identification and participation in political parties, focussing on formal aspects disregarding the content of political messages, promoting the implementation of short-term public policies, or contributing to the shortening of political shelf lives (see Newton, 2006, for a systematization of these arguments).

Empirical evaluations of media effects may be more or less pessimistic, but they tend to base themselves, either explicitly or implicitly, on a normative conception of the media focussed on their social responsibility (Siebert, Peterson, and Schramm, 1956), or more precisely, on the role the media should perform in a consolidated democratic society. Besides contributing to an informed citizenry via a regular, diverse, and timely delivery of meaningful information on important subjects, the media should foster a plurality of viewpoints on events and important aspects of society, and create fora in which candidates and political parties may present and debate ideas – a free marketplace of ideas, independent from government interference. The media should also serve as watchdogs, scrutinizing the actions of politicians on behalf of the citizens, thereby contributing to the accountability of political institutions (Lange, 2004; Voltmer, 2006).

In this article we uphold the idea that the performance or the contribution of the media vis-à-vis the functioning of a parliamentary democracy is dependant upon context. This argument stems from the apparent variety of media systems in contemporary democracies (Hallin and Mancini, 2004, 2012), as well as from the seeming connection between the macro context and the understanding of the role and performance of the media. To be concrete, many of the studies that focus on the negative effects of media exposure were carried out in the USA or in other highly commercialized contexts, while a considerable proportion of those concerning the positive impact of mass media (increase in the political information of less educated citizens, increase in political participation) make use of empirical data collected in less liberal and commercialized systems, such as those of northern Europe (Santana-Pereira, 2012).

The purpose of this article is to analyze the structure of the Portuguese media context and the performance of the Portuguese media from the standpoint of their normative roles, in comparison with other European Union member states. Our aim is to comparatively evaluate the contribution of mass media to the quality of the democratic process, namely through the performance of functions deemed important to this process: providing relevant information, airing different points of view on major current issues, creating debate arenas for different political agents, and scrutinizing the activity of institutions and of those who hold political office.

The article is divided into four sections. After the definition of media system and the presentation of the theoretical model and the data used in this work, we analyze the structure of the Portuguese media system in comparison with other European systems, an analysis that is further enriched by a consideration of the pluses and minuses of the Portuguese system and their consequences. Next, the analysis centers on the normative roles of the Portuguese media from a comparative perspective. The last section is dedicated to the relationship between structural patterns and media systems performances. The paper closes with a discussion of the implications of the empirical patterns observed.

MEDIA SYSTEMS: DEFINITIONS, DIMENSIONS, DATA

A media system can be defined as a network of media outlets – television channels, newspapers and magazines, radio stations, and internet sites – that exist, interact, and compete in a certain geographic area within the same historical period, serving the same population, using the same language and the same cultural codes, acting under the same legal framework, and meeting identical political, economic, and social constraints. In many cases these geographic areas correspond to countries, but when justified by cultural and linguistic diversity, one country may harbor two or more media systems. In Belgium, for instance, Flanders and Wallonia constitute two independent systems. On the other hand, when cultural and linguistic proximity allow, a transnational media system may come into being.

In 2004 Daniel Hallin and Paolo Mancini proposed one of the most useful and valuable analysis models for media systems. In Comparing Media Systems, the authors characterize the media systems of 18 Western European and North American countries, rating them according to four dimensions: the development of the press market, political parallelism (i.e., the existence of close connections between media outlets and political parties which, in extreme cases, would mean that each party would have, within the media system, a newspaper or television channel that would represent its views), the professionalization of journalists, and the degree of intervention by the state. Hallin and Mancini (2004) assert that, within the set of countries studied, there are three different kinds of media systems: liberal systems, like the British and North-American; democratic corporativist systems, typical of Scandinavian countries and western Europe; and the polarized pluralistic systems of southern Europe (Spain, France, Greece, Italy, and Portugal).

The expression polarized pluralism originates in Giovanni Sartoris (1976) typology of party systems and seeks to underscore the parallelism between the party systems present in southern European nations (polarized and pluralistic) and a politicized media sphere that is also polarized and pluralistic (Hallin and Mancini, 2004, 2010). Apart from the close relationships between media and parties, these systems stand out from the other two configurations (liberal and corporative democratic) by virtue of their fragile and underdeveloped press markets, the low professionalization of journalists, and a considerable intervention by the state in the domain of mass media (Hallin and Mancini, 2004).

It must be stressed that Portugals inclusion in this cluster has been criticized, due especially to the lesser political parallelism of the Portuguese system when compared to Italy or Spain (Traquina, 2010; Santana-Pereira, 2012; Álvares and Damásio, 2013) – a feature that is actually acknowledged by the authors (Hallin and Mancini, 2004, 2010). After all, one should bear in mind that the Spanish press sector has been nicknamed paper parliament (Schulze-Schneider, 2009), and that in Italy privileged connections between politics and the media have been promoted by a number of protagonists (Ricolfi, 1997; Padovani, 2009). In the Portuguese case, political parallelism may have become less salient after the stabilization of the democratic regime (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). Portugal is, following Denmark, the European Union member state in which the political proclivities of the most important journalists are less perceived by the public (Popescu et al., 2012); furthermore, about half of the Portuguese citizens have no opinion concerning the political stances of the media (Magalhães, 2009). Portugal may be one of the less polarized among the polarized pluralist systems of southern Europe, owing to a set of reasons that have been identified (Hallin and Mancini, 2010) but still need further empirical study. Nevertheless, the inclusion of the Portuguese case in a cluster composed of the other southern European democracies is more consensual when based on criteria such as press market development patterns or journalist professionalization, since, when these features are analyzed, it is clear that Portugals media system is closer to that of Spain or even Italy than to any western or northern European country.

In the next section we use the model proposed by Hallin and Mancini (2004) to analyze the Portuguese media panorama from a comparative standpoint. More specifica lly, we operationalize the models four dimensions with updated data. The origins of the data are quite diverse: the degree of political bias of the media and the professionalization of journalists are operationalized resorting to the data gathered by the European Media Systems Survey (EMSS)1 an expert survey (Popescu, Gosselin and Santana-Pereira, 2010; Popescu et al., 2012), while the States influence in the media realm and the development of the press market are gauged through data made available by the European Audiovisual Observatory and the World Association of Newspapers (EAO, 2010; WAN, 2010). Regarding the perceptions of media performance, discussed in the last sections of this article, the comparative focus is empirically based on the opinions of experts inquired by the EMSS project, while the analysis of the Portuguese case is enriched with data from public opinion surveys carried out in the last five years (Costa Pinto et al., 2011; BQD, 2014). The objectives of this article are carried out through the study of 26 member states of the European Union in 2009.2 This is the only year for which there are comparable data for all the variables, and also the last year before the spreading and deepening of the economic crisis across several European nations.

THE PORTUGUESE MEDIA SYSTEM IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

According to Hallin and Mancini (2004), the degree of press market development can be evaluated through indicators such as market size (in terms of number of readers, buyers, and/or subscribers), the balance between time dedicated to the reading of newspapers and time spent watching televised content, the diversity of the choices available to readers, and the difference between the newspaper consumption habits of men and women. In this article we use the first indicator – relative market size, measured by the average circulation of daily newspapers per million inhabitants – not just because this index provides a clear idea of the quantitative aspect of market development, but also because it is strongly correlated with the other indicators mentioned above in 2009 (Santana-Pereira, 2012), and is thus the most encompassing measure of development at our disposal.3

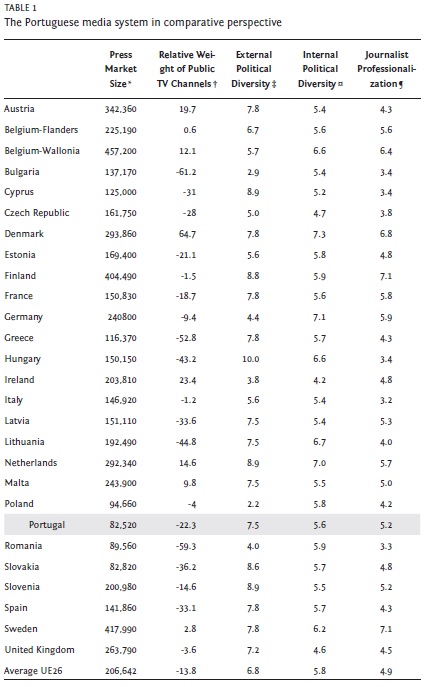

The Portuguese media panorama is often described as having a weak press market, with a small number of titles that are not read by the general public but, instead, by a small segment of the population, an elite (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). In 2009 Portugal was the European Union country with the lowest circulation of daily newspapers per million inhabitants. Still, Portugal was not an exceptional case in the European universe: the volume of newspaper circulation in the whole of southern and eastern Europe was also very modest (Table 1).

Färdigh (2010) and Santana-Pereira (2012) report the existence of a strong correlation between the volume of newspaper circulation and GDP per capita, the former being higher in wealthier societies. This being said, it is not surprising to find that newspaper reading seems to be a solidly widespread habit in countries like Austria, Finland, Sweden, and the French-speaking community in Belgium. In such contexts the average circulation varies between 342,000 and 457,000 copies per million inhabitants (Table 1).

The small dimension of the Portuguese press market strengthens the argument that Portuguese newspapers play an imperfect role as vehicles of vertical communication between the common citizen and the political elites, tending to work more as an instrument of horizontal communication among elites (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). Furthermore, the small size of the Portuguese market entails inherent problems with profits and liquidity, which may pose serious problems to the long-term survival of newspapers, as well as weaken their ability to withstand political and economic pressures. In 2009 the size of the press market was negatively correlated with the amount and degree of political and economic threats on the freedom of the press. The Portuguese case was, nonetheless, deviant: despite its small and underdeveloped press market, the economic and political pressures resulting in threats to press freedom were negligible (Santana-Pereira, 2015).

The Portuguese press market forecasts are anything but sunny. To start with, newspaper circulation has suffered a notable slump in the last few years, going from about 536 million in 2009 to about 383 million in 2013.4 The number of copies sold and distributed free of charge in 2013 amounted to 70% of the figures recorded four years earlier. The number of newspaper and magazine titles had, in 2013, regressed to that of 1995, with a remarkable decrease in printed newspapers (the number of newspapers simultaneously offered in print and online has remained stable since 2009/2010). Presumably, most of these defunct titles belong to regional and local newspapers, though some important national titles have also disappeared from the newsstands during the last decade, namely: Comércio do Porto and A Capital (2005), Independente (2006), the tabloid 24 Horas (2010), and the free newspapers Meia Hora and Global Notícias (2009 and 2010).

Let us now analyze the intervention of the State in the media sphere. According to Hallin and Mancini (2004), the strongest form of state intervention is the ownership and financing of the public television broadcasting service, along with some important aspects of industry regulation. In this article, for the sake of parsimony, our comparative analysis focusses on only the relative weight of public channels vis-à-vis the private television operators concerning audiences. However, we should mention that in 2009 77% of the funding received by RTP (the public television operator) was provided by the state (a value close to the EU average), and that the legal constraints to freedom of the press were, in Portugal – a country whose television sector was wildly deregulated (Traquina, 1995) – notably low (EAO, 2010; Freedom House, 2010). Generally speaking, there does not seem to be a strong connection between the degree of commercialization of the television subsystem and the reliance on state funding by the public broadcasters, but the systems in which such broadcasters maintain a reasonable ability to attract audiences tend also to be the ones in which regulatory constraints to freedom of the press are weaker (Santana-Pereira, 2012).

RTP started to lose the audience ratings battle during the mid-1990s, in part due to the bold style initially adopted by SIC and, in the following decade, by TVI. In 2009 the Portuguese television scene was clearly commercialized, and the difference in audience share between the public channels and the privately owned ones was above 20% (Table 1). In Europe the general trend is for the private channels to reach, on average, more than 14% of audience share than their public counterparts, although most member states possess highly commercialized panoramas. In countries such as Bulgaria and Romania, public television is absolutely irrelevant in terms of audience. This same pattern can be observed, although to a lesser extent, in the remaining eastern (except for Poland) and southern (except for Italy) European countries. In these two exceptional countries, as well as in the United Kingdom, Finland, Flanders, and Sweden, the balance between the relative strength of public and private channels is remarkable, revealing the existence of a television market duopoly, or of a dual television system (Ricolfi, 1997; Curran et al., 2009; Filas and Planeta, 2009; Padovani, 2009). Denmark is the only European Union country where public channels attract almost two thirds of TV audiences (Santana-Pereira, 2012, 2015).

The Portuguese television panorama is, thus, more commercialized than the European average, although following the trend seen in most European media systems. Worries about the relative weakness of public television have at their core the fear that private channels dedicate a small amount of air time to news content and offer audiences information of lesser quality (de Vreese et al., 2006; Curran et al., 2009; Iyengar et al., 2010; Aalberg, van Aelst and Curran, 2010, 2012). If the quantity and quality of the information presented by public channels are greater than that of the private ones, and if the majority of the population does not follow public channels, the probability of exposure to quality news content is considerably reduced. This obviously relies on the assumption that the public channels provide a public service to citizens, and are politically independent. In reality, the quality of the services delivered and the independence of the public television channels vary substantially across Europe (Hanretty, 2011; Popescu et al., 2012). In the Portuguese case, in 2009 public channels indeed offered more news content than their private counterparts, although there were no substantial differences in terms of the quality of the information provided (Santana-Pereira, 2015).

Besides having an underdeveloped press market and a commercialized television landscape, the Portuguese media system is also characterized by a considerable level of concentration. While the United Kingdom or Austria are good examples of systems with monomedia concentration patterns, in which the ownership of a specific activity sector (television, radio, press) is concentrated in a few hands (Humphreys, 2009; Thiele, 2009), Portugal is, together with other countries of southern Europe, a country where cross-media concentration patterns predominate. For instance, Impresa controls a generalist channel (SIC), several cable channels, a weekly newspaper (Expresso), and a news magazine (Visão), among other titles of non-news content; Media Capital controls a number of generalist and cable channels, some radio stations, and a web portal (IOL); Controlinveste (rebranded Global Media Group in 2014) owns a radio station (TSF) and the newspapers Diário de Notícias and Jornal de Notícias.

Media ownership concentration is considered a threat to editorial independence (Hanretty, 2014) and to the plurality of viewpoints in the media market, impacting both external and internal political diversity. In a system with high levels of external diversity there is a strong parallelism between the media and the party system: each media outlet is clearly associated with a given political party or ideological area. High levels of external diversity imply low levels of internal diversity, which is to say, pluralism or balance within each individual media outlet (Voltmer, 2000). Nevertheless, individual bias leads to diversity at the system level only if different sides of the ideological spectrum or the government/opposition divide are supported. Diversity (either internal or external) is a fundamental requisite for the enhancement of debate in the public sphere.

The data presented in Table 1 allow us to analyze the internal and external diversity of the Portuguese media system from a comparative standpoint. The external political diversity indicator is obtained through the difference between media outlets supportive of left-wing and right-wing parties,5 and has been recoded in order to be easily compared with the internal diversity indicator presented in the next column. Before analyzing these data, we should make some points clear. First, in building the external diversity indicator we took into consideration only the existence of partisanship in the media, independently of its degree, which may be moderate or intense; furthermore, the data concern only the seven to ten most important newspapers and TV channels in each country. Second, there is a great potential for external diversity fluctuations in fluid party systems, like those of the new democracies of eastern Europe (Mancini and Zielonka, 2012), and in consolidated systems in which control over state television can cause editorial interferences. As a result, the picture presented here may not match the present situation, which is impossible to analyze due to lack of comparative data. Lastly, this indicator should be read jointly with the internal diversity one, using the following key: 1) low to moderate levels of internal and external diversity indicate the existence of moderate to serious political biases in the media system, favoring just one side of the ideological/party spectrum; 2) low to moderate levels of external diversity and high levels of internal diversity mean that several neutral or pluralistic media outlets are present in contrast with few politicized media defending just one side of the spectrum; 3) high levels of external diversity and low to moderate levels of internal diversity reflect a polarized but pluralistic system; 4) finally, high levels in both indicators reflect the coexistence of pluralistic media outlets and of partisan media that support different political ideas.

In 2009 the majority of the European media systems were closer to a type 3 model, meaning a pluralistic and diversified environment. Germanys is the only type 2 system, due to the fact that most of the media considered biased stood close to the same political party in 2009: CDU (Christlisch Demokratische Union; Christian Democratic Union). Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Ireland, Italy, Poland, and Romania are type 1 systems, in which political-partisan biases seems more serious. In the Italian case this was due to the fact that Silvio Berlusconi, owner of the three main private TV channels and a number of newspapers, was also prime-minister, a fact that negatively affected the editorial independence of the RAI public channels (Padovani, 2009). Finally, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden are type 4 systems, in which two media subsystems seem to coexist (a neutral or internally diversified television system, and a press system that is relatively committed politically, creating a context of external diversity).

In Portugal, although the television channels are considered more biased than the newspapers (notwithstanding the fact that Público and JN are seen as more pluralistic than Expresso or Correio da Manhã), there seems to have existed, in 2009, some plurality within this television subsystem, with the public channels showing some pro-government (or pro-socialist) tendencies and the private stations exhibiting some sympathy toward the right-wing parties, i.e. the opposition with previous government experience (Popescu et al., 2012). There is a difference between the Portuguese and Spanish systems that is not apparent from the analysis of the data presented in Table 1 and that is worth pointing out: although both systems show relatively high levels of external diversity, the media that exhibit bias toward a specific party do so much more intensely and blatantly in Spain than in Portugal (see Popescu et al., 2012).

The fourth and last dimension proposed by Hallin and Mancini (2004) for the analysis of the European media systems is the professionalization of journalists. Here the term professionalization does not refer to the existence of a specialized body of knowledge acquired through formal and/or professional education, but rather to the autonomy of the journalist as a professional within the organization she works for, a set of values that makes her perceive her work as a service to the public, and the adoption of an internal code of professional norms (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). The professionalization index included in Table 1 is composed of items from the EMSS that were especially conceived to operationalize those conceptual elements.

Portugal is positioned favorably regarding this indicator, when compared both to the European countries taken as a whole and to the other southern European democracies. The professionalization of Portuguese journalists is greater than that of their colleagues in Spain, Greece, and chiefly, Italy – the least professionalized in the European Union, on a par with Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Cyprus (Table 1). The highest levels of journalist professionalization are found in Scandinavia. However, in a European context in which the average value for this index (4.9) is slightly lower than the middle point of the scale (5), one has to conclude that the professionalization of European journalists is, in general, rather modest. In the Portuguese case, the relative advantage over other nations belonging to the same geographic region does not mask the fact that the professionalization levels found in the country are modest.

The professionalization of journalists is a relevant factor because of the impact it may have on the quality of information, and for its boosting effect in journalists ability to resist pressures by political and economic agents. The quality of the information offered by the Portuguese media is, in fact, comparatively better that that of southern and eastern European nations, where journalist professionalization levels are lower (Popescu et al., 2012). Furthermore, the professionalization indicator is negatively correlated with the existence of threats to the freedom of the press in the set of countries under analysis (Santana-Pereira, 2015).

PERCEPTIONS OF MEDIA PERFORMANCE

In the previous section we characterized the Portuguese media system in structural terms, based on the analytic model suggested by Hallin and Mancini (2004). What follows is a performance evaluation of the Portuguese system regarding its normative roles. We shall assess, specifically, the extent to which the media help people to be informed on important issues, create room for the disputing of different political ideas, present diverse points of view on important subjects, and keep under check and scrutinize the activity of governments. For this purpose we will employ the opinions of the experts queried in the EMSS project (Popescu et al., 2012), which offer us a systemic comparative perspective, and data collected by a survey carried out during the first quarter of 2014, on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the April Revolution, that included questions aimed at measuring the normative performance of the media (BQD, 2014). This analysis is further complemented by data from the survey conducted in 2011 by the Barómetro da Qualidade da Democracia (Costa Pinto et al., 2012).

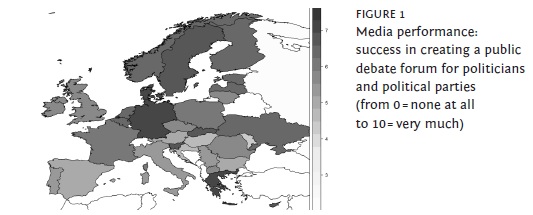

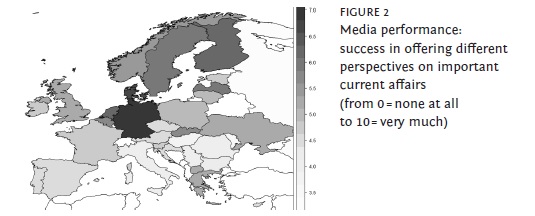

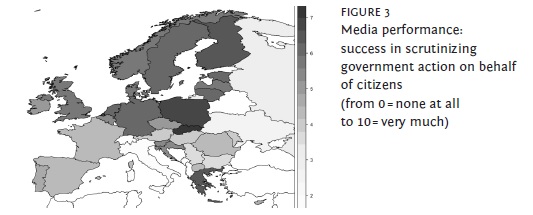

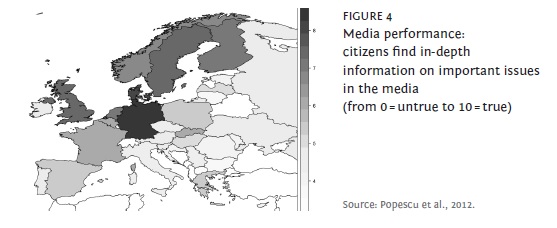

Among the four ascribed roles – to inform, to provide a forum for debate, to offer different perspectives on the same issue, and to act as watchdog – the Portuguese media fare better, according to the experts asked in the EMSS project, in the second one, scoring 5.3 on a scale of 0 to 10. The remaining functions score slightly lower, between 4.5 and 4.9 on the same scale (Popescu et al., 2012; Figures 1 to 4.)

Citizens seem to be more optimistic than communication and politics experts: their media performance assessments vary between 7.7 and 8 (BQD, 2014). Media outlets are, therefore, perceived by the public as actors that contribute in a positive way to the quality of democracy. Furthermore, 69% of the Portuguese people consider that allowing greater media access to the reasons and criteria used by the government in the decision-making process is an effective vertical accountability measure, and 48% think that attracting media attention to a given issue is an effective form of political engagement, even if only a minority believe in the capacity of the media to stop government abuse (Costa Pinto et al., 2012). All in all, the Portuguese media are essentially perceived as privileged agents with access to information about the backstage of the governmental or political spheres, that offer this information to the citizens and to representatives of other democratic institutions that can (and should) have the resources to act upon it.

In comparative terms (Figures 1 to 4), there seems to be a considerable difference between northern and southern European countries regarding these performance indicators. Such differences appear more pronounced in the case of the availability of in-depth information and of variety of perspectives. Within the cluster of polarized pluralist countries (Spain, France, Greece, Italy, and Portugal), the situation of Portugal tends to be more positive than the one identified in Italy, similar to the situation of the Spanish and French systems, and slightly less positive than the pattern identified by the Greek experts. Generally speaking, we can say that Italy was in 2009 the polarized pluralistic media system with the poorest performance, a fact that puts this country in line with new democracies of Eastern Europe such as Romania and Bulgaria.

THE STRUCTURE AND NORMATIVE PERFORMANCE OF MEDIA SYSTEMS

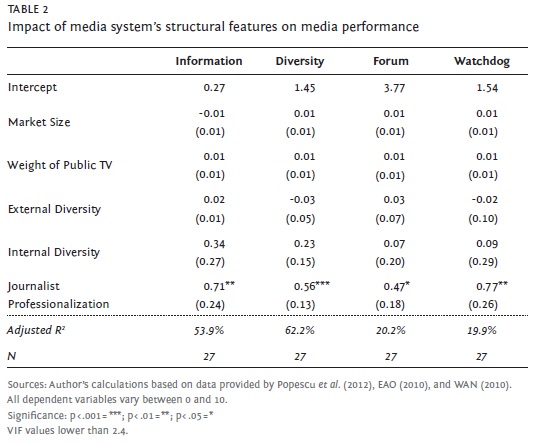

To what extent do the structural dimensions of media systems contribute to a more or less favorable performance of the media? In Table 2 we present the results of four linear regression models – one for each performance indicator – in which the impact of the five structural variables (market size, relative weight of public television, internal and external diversity, and journalist professionalization) is assessed.

The robustness of the results was tested by the estimation of other regression models with control variables related to economic wellbeing and to the educational standards of the population, as well as to the age of the democratic regime.6 Due not only to a high ratio between the number of variables and cases, but also to the strong correlation between some of these factors and the wish to avoid multicolinearity, we opted to include the factors to be controlled one at a time, meaning that for each dependent variable three regression models with control variables (one for each variable) were estimated. Space restrictions prevent us from presenting here the results of these regressions, but they are available upon request.

The level of journalist professionalization was the most important factor of media performance in the EU member states in 2009. Its impact is quite remarkable: if the remaining four factors are kept constant, a one-point increase in this indicator leads to a 0.77 increase in the scrutiny index, 0.71 in the in-depth information index, 0.56 in the diversity index, and 0.47 in the debate fora creation index (Table 2). It is, furthermore, a robust effect that maintains its significance even after the introduction of the control variables.7

Nevertheless, the explanatory power of the model is far greater when it comes to the provision of in-depth information and diversity of viewpoints on important issues (Table 2). The proposed model explains more than 50% of the variation in these two dependent variables, while accounting for just one fifth of the variation in the other performance indexes. This mostly happens not because the journalist professionalization index has a different explanatory capacity, but because the internal diversity index tends to have a positive impact on the quality and variety of the information provided by the media (although not statistically significant owing to the small number of cases under analysis), while being irrelevant to the remaining dependent variables.

CONCLUDING NOTES

The purpose of this article was to analyze the main features of the Portuguese media system in the context of the European Union. The analysis endorses the conclusion that several years after the publishing of the already classic book by Daniel Hallin and Paolo Mancini (2004), Portugal, the least polarized of the polarized pluralistic media systems, continued to be less polarized than the Spanish and Italian systems. The Portuguese press market is rather underdeveloped, posing obstacles to the survival of some titles. The professionalization levels of Portuguese journalists are on a par with the European average, but objectively low. Regarding state intervention, in an indisputably commercialized TV context, the State was responsible for injecting three quarters of the financial resources required by the public television service. On aggregate, despite some differences from the picture painted by Hallin and Mancini in 2004, Portugal still exhibits the main features that characterize the southern European cluster, particularly regarding the press market and its journalists.

Regarding the normative performance of the media, in terms of availability of quality information and diverse viewpoints, of the creation of spaces for political debate, and of government activity scrutiny, Portugal resembles, once more, other pluralistic polarized systems. The general panorama is, nevertheless, more positive in Portugal than in Italy, where the media seem to be lacking in the fulfilment of their normative roles. In any case, Portuguese experts show little enthusiasm about the performance of their media, ranking it well below the frankly positive evaluation made by the general public. All in all, the Portuguese media count themselves among the good students of southern Europe, but their performance lags well behind their western and northern European counterparts.

Lastly, the performance of the media seems to depend to a great extent on the levels of journalist professionalization. Therefore, it will be necessary to further encourage this professionalization in order to better the medias contribution to the democratic process. What can be done to secure high professionalization of the journalistic class? There is no clear-cut answer to this question, but there are some paths – many of them winding and complex – that may lead to improvement. First, the training of new generations of journalists must ensure that their career preparation includes not only the acquisition of technical skills, but a solid ethical and deontological component as well. Second, the media system must be regulated and supervised in order to neutralize political, legal, and economic threats that diminish the professionalization of this class (Santana-Pereira, 2015). On the one hand, this may imply the setting up of arrangements that guarantee the different political parties effective access to and an equitable and unbiased presence in the media, in order to reduce the amount of political coercion or the need to establish privileged relationships with certain journalists. On the other hand – and perhaps more importantly – it is crucial to find ways to fight job insecurity among journalists (a particularly worrying aspect in the Iberian Peninsula), since it may encourage the public service norm to take a back seat in relation to the pressing need to keep a job position. Considering that one of the causes of job insecurity within journalism is the frailty and underdevelopment of the press market, and that these arise mainly from the fact that large portions of the population lack the habit of accessing information through newspapers, the socialization processes of the new generations (in schools and other institutions) should be oriented toward fostering reading habits and conveying the importance of being well informed.

Finally, one must underscore the fact that the analysis reported here portrays the European media systems during a period quite different from the one that the Old Continent is presently experiencing. The data analyzed in this article are from 2009, and were thus collected before the onset of the financial crisis that, especially in the frailest member states, entailed several consequences for citizens, media organizations, political parties, and protagonists. Therefore, it is probable that some of the patterns mentioned need to be re-evaluated under this new context. There is, in fact, some empirical evidence that the situation with some media systems in the south and east of the European Union has been worsening during the last six years. Freedom House, for instance, has been signalling the erosion of press freedom in countries like Greece and Hungary, but also in Spain, the UK, and Cyprus.8 Also, the absence of trustworthy comparative data made it impossible for the analysis of the structural dimensions and performance carried out here to be extended to the last five years. Future research into this subject should, therefore, seek to produce data that allow us to draw a picture of the European media systems in times of crisis.

REFERENCES

AALBERG, T., VAN AELST, P. and CURRAN, J. (2010), Media systems and the political information environment: a cross-national comparison. International Journal of Press/Politics, 15 (3), pp. 255-271. [ Links ]

AALBERG, T., VAN AELST, P. and CURRAN, J. (2012), Media systems and the political information environment: a cross-national comparison. In T. Aalberg and J. Curran (orgs.), How Media Inform Democracy: a Comparative Approach, Nova Iorque, Routledge, pp. 33-49. [ Links ]

ÁLVARES, C. and DAMÁSIO, M.J. (2013, Introducing social capital into the 'pluralist polarised' model: the different contexts of press politicisation in Portugal and Spain. International Journal of Iberian Studies, 26 (3), pp. 133-153. [ Links ]

BDQ – Barómetro da Qualidade da Democracia (2014), Inquérito Sobre os 40 Anos do 25 de Abril, Dataset, Lisbon, ICS. [ Links ]

CHAFFEE, S.H. and KANIHAN, S.F. (1997), Learning about politics from the mass media. Political Communication, 14 (4), pp. 421-430. [ Links ]

COSTA PINTO, A. et al. (2012), A Qualidade da Democracia em Portugal: a Perspectiva dos Cidadãos, First Report, Lisbon, ICS. [ Links ]

CURRAN, J., et al. (2009), Media system, public knowledge and democracy: a comparative study. European Journal of Communication, 24 (1), pp. 5-26. [ Links ]

DE VREESE, C.H. and BOOMGAARDEN, H. (2006), News, political knowledge and participation: the differential effects of news media exposure on political knowledge and participation. Acta Politica, 41 (4), pp. 317-341. [ Links ]

DE VREESE, C.H. et al. (2006), The news coverage of the 2004 European Parliament election campaign in 25 countries. European Union Politics, 7 (4), pp. 477-504. [ Links ]

DRUCKMAN, J.N. (2005), Media matter: how newspapers and television news cover campaigns and influence voters. Political Communication, 22, pp. 463-481. [ Links ]

EAO – European Audiovisual Observatory (2010), Yearbook 2010 – Television in 36 States, Estrasburgo, EAO. [ Links ]

EVELAND, W.P. Jr. and SCHEUFELE, D.A. (2000), Connecting news media use with gaps in knowledge and participation. Political Communication, 17 (3), pp. 215-237. [ Links ]

FÄRDIGH, M.A. (2010), Comparing media systems: identifying comparable country-level dimensions of media systems. QoG Working Paper Series, 2, Göttenborg, University of Göttenborg. [ Links ]

FILAS, R. and PLANETA, P. (2009), Media in Poland and public discourse. In A. Czepek, M. Hellwig and E. Novak (orgs.), Press Freedom and Pluralism in Europe: Concepts and Conditions, Bristol, Intellect, pp. 141-163. [ Links ]

FREEDOM HOUSE (2010), Freedom of the Press 2010: Broad Setbacks to Global Media Freedom, New York, Freedom House. [ Links ]

HALLIN, D.C. and MANCINI, P. (2004), Comparing Media Systems. Three Models of Media and Politics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

HALLIN, D.C. and MANCINI, P. (2010), Comparing media systems: a response to critics. Media & Jornalismo, 9 (2), pp. 53-67. [ Links ]

HALLIN, D.C. and MANCINI, P. (2012), Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

HANRETTY, C. (2011), Public Broadcasting and Political Interference, Oxon, Routledge. [ Links ]

HANRETTY, C. (2014), Media outlets and their moguls: why concentrated individual or family ownership is bad for editorial independence. European Journal of Communication, 29 (3), pp. 335-350. [ Links ]

HUMPHREYS, P. (2009), Media freedom and pluralism in the United Kingdom. In A. Czepek, M. Hellwig and E. Novak (orgs.), Press Freedom and Pluralism in Europe: Concepts and Conditions, Bristol, Intellect, pp. 197-211. [ Links ]

IYENGAR, S., et al. (2010), Cross-national versus individual-level differences in political information: a media systems perspective. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 20 (3), pp. 291-309. [ Links ]

LANGE, B. (2004), Media and elections: some reflections and recommendations. In B.-P. Lange and D. Ward (orgs.), Media and Elections. A Handbook and Comparative Study, Mahwah, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 203-231. [ Links ]

LAZARSFELD, P.F., BERELSON, B. and GAUDET, H. (1944), The Peoples Choice: How the Voter Makes up his Mind in a Presidential Campaign, New York, Duell, Sloan, & Pearce. [ Links ]

LUNDBERG, G.A. (1926), The newspaper and public opinion. Social Forces, 4 (4), pp. 709-715. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, P. (2009), A Qualidade da Democracia em Portugal: a Perspectiva dos Cidadãos, Preliminary Report, Lisbon, ICS-UL. [ Links ]

MANCINI, P. and ZIELONKA, J. (2012), Introduction. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 17 (4), pp. 379-387. [ Links ]

NEWTON, K. (1999), Mass media effects: mobilization or media malaise?. British Journal of Political Science, 29 (4), pp. 577-599. [ Links ]

PADOVANI, C. (2009), Pluralism of information in the television sector in Italy: history and contemporary conditions. In A. Czepek, M. Hellwig and E. Novak (orgs.), Press Freedom and Pluralism in Europe: Concepts and Conditions, Bristol, Intellect, pp. 289-304. [ Links ]

POPESCU, M., GOSSELIN, T. and SANTANA-PEREIRA, J. (2010), European Media Systems Survey 2010, Dataset, Colchester, Department of Government, University of Essex. URL: www.mediasystemsineurope.org. [ Links ]

POPESCU, M. et al. (2012), European Media Systems Survey 2010: Results and Documentation, Report, Colchester, Department of Government, University of Essex. URL: www.mediasystemsineurope.org. [ Links ]

PUTNAM, R.D. (1995), Tuning in, tuning out: the strange disappearance of social capital in America. PS: Political Science and Politics, 28 (4), pp. 664-683. [ Links ]

RICOLFI, L. (1997), Politics and the mass media in Italy. West European Politics, 20 (1), pp. 135-156. [ Links ]

ROBINSON, M.J. (1976), Public affairs television and the growth of political malaise: the case of The Selling of the Pentagon. American Political Science Review, 70 (2), pp. 409-432. [ Links ]

SANTANA-PEREIRA, J. (2012), Media Systems and Information Environments. A Comparative Approach to the Agenda-setting Hypothesis. Doctoral Dissertation, Florence, European University Institute. [ Links ]

SANTANA-PEREIRA, J. (2015), Variety of media systems in third-wave democracies. In J. Zielonka (org.), Media and Politics in New Democracies: Europe in a Comparative Perspective, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

SANTANA-PEREIRA, J. (2016), The media as a window on the past? The impact of television and newspaper consumption on knowledge of the democratic transition. South European Society and Politics, 21 (2), pp. 227-242. [ Links ]

SARTORI, G. (1976), Parties and Party Systems: a Framework for Analysis, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

SCHULZE-SCHNEIDER, I. (2009), The freedom of the Spanish press. In A. Czepek, M. Hellwig and E. Novak (orgs.), Press Freedom and Pluralism in Europe: Concepts and Conditions, Bristol, Intellect, pp. 275-288. [ Links ]

SIEBERT, F.S., PETERSON, T. and SCHRAMM, W. (1956), Four Theories of the Press, Urbana, University of Illinois Press. [ Links ]

THIELE, M. (2009), The Austrian media system: strong media conglomerates and an ailing public service broadcaster. In A. Czepek, M. Hellwig and E. Novak (orgs.), Press Freedom and Pluralism in Europe: Concepts and Conditions, Bristol, Intellect, pp. 251-259. [ Links ]

TRAQUINA, N. (1995), Portuguese television: the politics of savage deregulation. Media, Culture and Society, 17 (2), pp. 223-238. [ Links ]

TRAQUINA, N. (2010), Prefácio. In D.C. Hallin and P. Mancini (eds.), Sistemas de Media: Estudo Comparativo. Três Modelos de Comunicação e Política, Lisbon, Livros Horizonte. [ Links ]

VOLTMER, K. (2000), Structures of Diversity of Press and Broadcasting Systems: the Institutional Context of Political Communication in Western Democracies, Discussion Paper FS III 00-201, Berlim, WZB. [ Links ]

VOLTMER, K. (2006), The mass media and the dynamics of political communication in processes of democratization. In K. Voltmer (org.), Mass Media and Political Communication in New Democracies, Oxon, Routledge, pp. 1-19. [ Links ]

ZHAO, X. and Chaffee, S.H. (1995), Campaign advertisements versus television news as sources of political issue information. Public Opinion Quarterly, 59 (1), pp. 41-65. [ Links ]

WAN – World Association of Newspapers (2010), World Press Trends – 2010 edition, Paris, WAN. [ Links ]

Received 29-09-2015. Accepted for publication 22-01-2016.

NOTAS

1More than 800 experts took part in this project: academics from prestigious universities with scholarly work and/or teaching experience in the fields of political communication, the relationships between politics and the media, and political attitudes and behavior. Each expert was invited to fill in a questionnaire regarding the profile of the media in their country of residence. Further information on the methodology used by the EMSS project is available in Popescu et al. (2012).

2The number of cases under analysis is 27, due to the fact that Belgium is composed of two systems: Flanders and Wallonia. Luxembourg is not included in the analysis owing to the absence of comparable data on media performance, journalist professionalization, and relationships between political parties and the media for this country. Croatia is not included in the analysis because in 2009 it was not yet an EU member state.

3A more detailed analysis of the structural features of the Portuguese press market can be found in Santana-Pereira (2012 and 2015).

4The data presented in this paragraph concerning the evolution of the Portuguese press market during the last few years is provided by Pordata (www.pordata.pt).

5In Santana-Pereira (2012), data on the external diversity of the European media systems regarding the government/opposition parties dichotomy are also presented and discussed. The correlation between the measure used in this article and that other measure is moderate and positive (Pearsons r=0.5; p<0.05).

6The control variables are the education index and the GDP per capita used to calculate the UN HDI (indexes described and data available in http://hdr.undp.org/en), as well as an index of democratic experience of societies in 2009 (with three levels: recent eastern European democracies, with fewer than 20 years of continuous existence; recent southern European democracies, with about 35 years of existence; older democracies).

7One of the control variables – GDP per capita – has a significantly positive impact on the relevant information availability index. Otherwise, the control variables have no significant statistical effect on the four dependent variables analyzed.