Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.211 Lisboa jun. 2014

FÓRUM

Sustainability beyond austerity: possibilities for a successful transition to a wellbeing society

Tim O'Riordan*

*School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia » Norwich, uk nr4 7tt. E-mail: t.oriordan@uea.ac.uk

OVERVIEW

This paper looks at the emergence of a lost economy and the end of a period of effective prosperity for the many. It highlights the beginnings of planetary constraints on long-established growth paradigms and supportive political institutions, and indicates the potential for social disruption and malaise of seeking to continue on such growth pathways. It analyses the literature on societal transitions to sustainability and finds these studies embryonic and wanting. It suggests that the coming decade will make or break the effectiveness of any meaningful transition to sustainability no matter how this deeply ambiguous concept is defined.

It begins by examining three prisms of profound dilemmas and searches for solutions based on emerging notions of wellbeing and enterprise and social investment.

THE FIRST PRISM OF DILEMMAS: UNEMPLOYMENT AND YOUNG PEOPLE

The Economic and Financial Affairs Directorate of the European Commission (2013, p. 5) put a brave face on its winter 2012/3 economic forecasts. It does not foresee any real growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the EU economy as a whole. Throughout 2014 it does not expect much beyond modest growth, largely dependent on stimulus packages and a small improvement in global trade. The European Commission (2014a) recognizes the persistence of structural impediments and very high rates of unemployment especially amongst the young. Meanwhile real incomes of the majority of EU households have fallen to levels of a decade ago, with no immediate expectation of any significant uplift. The Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR, 2012, p. 14), the independent economic forecasting organization in the UK, concludes that spending cuts and tax rises will continue to reduce real household incomes by the equivalent of 0.4 per cent of GDP each decade for decades to come. This is because of the very high social costs of providing adequate health and social care and extensive publicly supported pension contributions for a rapidly ageing population. Even with growth there will be overall income loss. The independent Institute of Fiscal Studies (Joyce, 2012) has reinforced this conclusion.

One immediate effect is the unprecedented vision of middle income and aspiring lower income households experiencing increasing living costs (in the form of increasing charges for fuel, for water, for food, for health, for pension contributions, and for mortgages) from a platform of declining incomes. This doleful prospect has not yet fully sunk in. When it does there will be destabilizing political repercussions as the squeezed middle class seek more responsive politicians to champion their cause. Few governments will be politically secure for more than a term. This is not conducive to promoting the kinds of courageous and visionary leadership which will be sought, and which is examined later in this paper.

Another immediate effect is the growth of unemployment, especially amongst the young. The Economist (2013a, pp. 59-61) estimates there could be as many as 500 million unemployed young people in the world. For the wealthier countries the main reasons for this are rigidity and protectionism of labour markets, lack of suitable vocational training and in-job further training, and poor matching of emerging skills with investment in technological innovation. The EU Commission (2014b) summarizes the current position:

More than 5.5 million young people are unemployed in the EU-28 area today.

This represents an unemployment rate of 23.4% (24.0% in the euro area). More than one in five young Europeans in the labour market cannot find a job; in Greece and Spain it is one in two.

7.5 million young Europeans between 15 and 24 are not employed, not in education, and not in training (NEET).

In the last four years, the overall employment rates for young people fell three times as much as for adults.

The gap between the countries with the highest and the lowest jobless rates for young people remains extremely high. There is a gap of over 50 percentage points between the Member State with the lowest rate of youth unemployment (Germany at 7.7% in December 2013) and the Member State with the highest rate, Greece (58.3% in December 2013). Greece is followed by Spain (54.6%), Croatia (49.8%), Italy (41.7%), Cyprus (40.3%) and Portugal (34.4%).

The unleashed potential of job mobility to help tackle youth unemployment remains to be further developed: the workforce in employment in the EU is around 216.1 million persons of which only 7.5 million (3.1%) are working in another Member State. EU surveys show that young people are the group most likely to be mobile.

There is a real danger that many millions of young adults staying at home could become a forgotten generation. EU policymakers and stakeholders are well aware of the potential social dangers, but fear they appear powerless to halt the rising unemployment among young people. Here is a comment from a policy think tank which specializes on this topic:

This is a huge problem to tackle, but it is essential that young people are encouraged to develop skills that are in demand and that they are given the chance to obtain meaningful work experience that enables them to gain a foothold in the labour market [Andrea Broughton of the Institute for Employment Studies 2012 http://www.employment-studies.co.uk/press/10_12.php]

The Princes Trust (2012), is a UK charity which specializes in providing leadership and work experiences for disadvantaged young people in the UK. It has found that two in five of youngsters not in employment, education, or training were deeply pessimistic about their ability to cope with their depressing lives. They exhibit very little self-confidence about their abilities to enter into any kind of meaningful work. Bell and Blanchflower (2009) found that young adults were at risk of being long term unemployed if they had an unemployed father, few or no qualifications, low work motivation, and if they were of Caribbean origin. Bell and Blanchflower (2009, p. 16) also state that unemployment while young, especially of long duration, causes permanent scars rather than temporary blemishes. They also found that for people even at the age of 40 a period of unemployment when young reduces annual income by between 9 and 21% (the more the loss the longer the period of being out of work). This is a huge aggregate cost to the coming generation especially in the light of rising housing costs and pension payments. As we shall see this will have a material effect on future wellbeing for the generation of family formers.

Unemployment and loss of competitive skills do not bode well for job opportunities arising from the green economy, in which high rates of commitment and flexible and adaptable skills transfer will be required (Environment Audit Committee, 2012). Stafford et al. also found that unemployed young people, from social class 4 and 5, or female, generally suffered from poor mental health (as measured by the General Health Questionnaire). This added to anxiety and depression which further inhibited motivation and self-confidence. When these young people actually got into some form of mentored work involvement their mental health improved and their levels of motivation increased.

Here is one challenging facet of the prism of dilemmas currently afflicting us. Young people who are vulnerable due to personal experiences of poverty, violence, and abuse, and who come from broken families and unmotivated parents, are seriously at risk from persistent unemployment.

To train them for the rapidly adaptive jobs of the emerging economic age will take a large investment in mentoring, in skills training, in confidence building, and in many qualities of social and work experiences. At present much of this resides in the public sphere of social investment. But nowadays that public sphere is shrinking fast and will probably never recover to its earlier levels of spending. One feature of the transition to sustainability beyond austerity, therefore, is the emergence of a more socially responsive private sector and charitable investment for transforming young people to meaningful enterprise and to responsible citizenship in its broadest sense. This facet will be examined later in this paper.

THE SECOND PRISM OF DILEMMAS: GROWING INEQUALITY

The UN Human Development Report (2005, p. 4) revealed the widening gap of income and social justice across the globe. Even then, the Report stated:

The richest 50 individuals in the world have a combined income greater than that of the poorest 416 million. The 2.5 billion people living on less than $2 a day – 40% of the worlds population – receive only 5% of global income, while 54% of global income goes to the richest 10% of the worlds population.

The Economist (13th October 2012) brings these figures up to date. The top 0.1% of Americans own more than 5% of US national income, a greater proportion than was the case in 1900. The Gini coefficient, a measure of the distribution of wealth, has shown a 30% to 50% increase in concentration of national wealth over the past decade. Globally the Gini coefficient is lowering due to growth in the emerging economies. But income inequality is widening in almost all nation states. With it come social tension, illness, civil disturbance, and lower growth rates.

In a study for the think tank, Share the Worlds Resources, Rajesh Makwana (2006) quoted the UNs Report on the Worlds Social Situation (2005), which claimed that:

Non-economic aspects of global inequality (such as inequalities in health, education, employment, gender and opportunities for social and political participation) are causing and exacerbating poverty. These institutionalised inequalities result in greater marginalisation within society. The report emphasises the inevitable social disintegration, violence and national and international terrorism that this inequality fosters. Ironically, the diversion of social development funds to national/international security and military operations produces further deprivation and marginalization, thus creating a vicious cycle.

According to the International Forum on Globalization (2005), 52 of the wealthiest 100 economic entities of the world are global corporations. These are bigger than many national economies; they are free to ignore national borders; they enjoy massive lobbying power; and they largely control the destinies of national finance ministries.

Action Aid (2012, p. 2) in its report Under the Influence spells out the connections:

Under the influence reveals a worldwide explosion of corporate lobbying which contributes to unfair trade rules that undermine the fight against poverty. The report highlights examples of privileged corporate access to, and excessive influence over, World Trade Organization policymaking process. In the EU alone, there are 15,000 lobbyists based in Brussels – around one for every official in the European Commission. Annual corporate lobbying expenditure in Brussels is estimated at 750 million to 1 billion. In the US, 17,000 lobbyists work in Washington DC – outnumbering US Congress lawmakers by 30 to one. Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry is reported to have spent over $1 billion lobbying in the US in 2004.

Another aspect of growing inequality is the sequestration of the wealth of individuals and corporations in tax havens or offshore financial centres. The Economist (16th February 2013) estimates up to $21 trillion lies in such centres compared to global total financial private wealth of $123 trillion. James Henry, a consultant for the Tax Justice Network (2012), believes that almost 30% of global financial direct investment is transacted through such centres. Indeed they are so powerful as to dominate banks and governments. The Economist survey suggests that these centres are resilient and will survive any moderately serious attempt at improving international financial regulation. There is no shortage of investment funds in the current flat-lining economies. There is only a carefully massaged shortage. It could significantly be liberated by the successful implementation of a financial transactions tax (the so-called Tobin tax). A charge of 0.01% on specified international transactions, the lowest rate of take being suggested, could yield up to $100 billion annually. This could be managed as social and environmental trust funds for progressive sustainability. But it continues to be blocked by a sophisticated combination of financial institutions and their heavyweight political backers, all carefully lobbied by the wealth of those which would be hardly affected by such a levy. The European Parliament has also continued to oppose any move to introduce this tax. Surely its day will come.

THE THIRD PRISM OF DILEMMAS: DEFINING PLANETARY BOUNDARIES

The UN Summit on Sustainable Development, colloquially referred to as Rio+20 to reflect the 20th anniversary of the UN commitment to global sustainability, received huge amounts of evidence of the scale of human influence on the life-force viability of the planet.

One of these was the international science convention, Planet under Pressure, held in London in March 2012. Its leaders concluded:

Research now demonstrates that the continued functioning of the Earths system as it has supported the wellbeing of human civilization in recent centuries is at risk. Without urgent action, we could face threats to water, food, biodiversity and other critical resources: these threats risk intensifying economic, ecological and social crises, creating the potential for a humanitarian emergency on a global scale [Brito et al., 2012, p. 3].

GEO 5: the fifth Global Environmental Outlook of the UN Environment Programme (2012, p. 5) reached similar conclusions:

As human pressures on the Earth system accelerate, severe critical global, regional and local thresholds are close or have been exceeded. Once these have been passed, abrupt and possibly irreversible changes to the life support functions of the planet are likely to occur, with significant adverse implications for human wellbeing.

These two massive scientific reports are buttressed by much painstaking evidence. One of these is a very useful and accessible summary of the drawdown of natural and social capital offered by Jules Pretty (2013). His conclusion that humanity is starting to stray outside the safe operating space for humanity acknowledges the impressive work by Johann Rockström et al. (2009) and extended in Rockström and Klum (2012). Rockström and his many colleagues claim to have the scientific evidence that humanity is near or past safe planetary boundaries in the areas of climate change, biodiversity loss, nutrient cycling, and ocean acidification.

Such grand conclusions always excite criticism. One such contested challenge (Nordhaus et al., 2012) applies to doubts that scientists do not enjoy the necessary levels of scientific understanding to define a boundary, let alone its location. Another concern is the geography and economy of limits. Nitrogen cycling caused by fertilizers in agriculture may breach a global boundary. But at the scale of impoverished agriculture better use of artificial fertilizer may be sustainable, and indeed vital for future food security. There is a whiff of scientific grandstanding about the planetary boundaries initiative. But this should not undermine its value in determining that the remaining ecological space within which future growth should roam, is ultimately confined but not tethered. What is more challenging is to encourage economists, business interests, the military, and beleaguered politicians, that there is indeed some framing of sustainable growth in an age of austerity. As we shall examine below, this is one task of the emerging sustainability science.

Nevertheless, the planetary boundaries initiative is guiding the work of the UN High Level Panel on Global Sustainability (2012) which asked for all future economic and social improvement to have regard for such boundaries. This initiative in turn is guiding a series of discussions over what to include in global sustainable development goals for all nations to agree to and to advance as an intrinsic purpose of their green and equitable future economic development paths. In order to achieve this, the aim is to devise measures of economic progress in terms of social wellbeing (including the wellbeing of all future generations), and to encourage governments and businesses to develop accounting procedures for incorporating the social and ecological effects of their commerce into their overall balance sheets. This will require more formal and comprehensive reporting with both international and national regulatory back-up.

The aim here is to coordinate better both international and national economic policy into a more sustainability orientated framework. This in turn will require improved measures of wellbeing (which will be addressed below), as well as much more formal means of incorporating wellbeing indicators into policy analysis at all scales of government . The trigger for all of this is the planetary boundaries concept, as this provides a frame for both the ceiling of resources and ecosystem services availability for any future growth, as well as the (bumpy) floor of social justice and dignity (bearing in mind the peaks and troughs of inequalities in every corner of the planet). At the heart of this important initiative lie the dilemmas already introduced above: reliable growth, resilient ecosystems, fairness of opportunity, and the removal of poverty, set within the struggle to break the bondage of austerity and unemployment.

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

We face a dilemma over the integrity of the various tried and largely failed socio-technical approaches to connecting growth to widened prosperity and to ecological maintenance. Walker and Shove (2011, p. 215) explore the role of ambivalence in revealing any transition to sustainability. They point out that sustainability actually thrives on lack of definition and multiple interpretations, especially of goals and mechanisms for reform.

The ordering function of language, and the cultural and political need to divide the world into the progressive and enlightened and the backward and undesired, made and makes this process both inevitable and irresistible. It was not possible to talk about sustainability, or to define it, without simultaneously unleashing its practical and political application and attachmentand hence its ambivalence.

This perspective has enabled a discussion of multiple layers of introducing sustainable transitions from global governance through national policies to local level citizen-based actions. This is not always a helpful framing as there are usually inadequate linkages between patterns of power and inequalities (as discussed above) and any scope for coordinated regulatory cooperation either in economic strategy or social betterment at each of these scales. Markand et al. (2012) provide a fine summary of the progress of this literature and research pathways. Walker and Shove assert that the very language of learning from experimentation combined with new combinations of concepts (sustainable prosperity sustainability science) add to confusion and distort understanding of achievement and aspiration. In essence, transitions to sustainability are difficult to conceptualize, problematic to research in supposedly value-free methodologies (because they necessarily involve interventionist and participatory approaches which can destabilize community actors), and are potentially biased by informal and formal power relations amongst the participants themselves (Avelino and Rotmans, 2010, p. 544).

Any transition also faces a form of power struggle between the forces of economic and social management and reformist approaches to transformation. Avelino and Rotmans consider this from both the power relations and the agent based perspectives. They also reflect on both elitist and pluralist power relations. In assessing all of these dimensions they reinforce the Walker/Shove triumphing of ambivalence. There may be no clear route to any sustainability transition. Indeed, the very frames of analysis are rooted in patterns of power relations and ways of thinking which inhibit genuine transformation. The dependence of reflexivity, on ecological modernization, on socio-technological innovation, on systems dynamics, and on creating accounting by businesses and governments, fly in the face of the kinds of institutional settings of anti-sustainability realities outlined above.

Shove and Walker (2007, p. 768) put all of this nicely in perspective:

We are wary of the notion that transition management, with its accompanying repertoire of concepts and tools, provides a neat model of how managers might intervene (albeit reflexively) to shape and modulate processes of change. We have observed that these approaches can all too easily obscure their own politics, smoothing over conflict and inequality; working with tacit assumptions of consensus and expecting far more than participatory processes can ever hope to deliver.

Maybe all that can be said here is that efforts to transform societies into sustainability require a degree of ambivalence, depend upon fresh approaches to action-based research, focus on people and their empathies and aspirations, and probe the ways in which governing institutions can be adjusted toward greater support and flexibility. Most important will be the shifts in conception of institutional blockages and innovative transformations which are as yet limited in both the theoretical and applied research literature. This sets the scene for the antidotes which follow.

ONE ANTIDOTE: SUSTAINABILITY SCIENCE

Science is the art of acquiring reliable and credible knowledge for peaceful survival of humans on this planet. The scientific community follows various tribal rules through which they prove for themselves that they meet this objective. In the past these rules demanded the test of proof against robust attempts to disprove underlying theories, hypotheses, and evidence. Science evolves by triumphing over scepticism. The community also seeks tests of independence and critique by its own exponents. So there has been a wish for public acceptance through profound internal scrutiny.

In recent decades it has become very clear that science is tangled with prejudice, with the bias of commercial interests, with the world of lobbying, and with the outburst of organized pressure and dissent. (For a comprehensive perspective, see Jasanoff (2012)).This turbulence is most clearly found in the vast domains of climate change science. Here the very fundamentals of evidence gathering, of theory building, and of modelling trends and abrupt discontinuities are being challenged (see Hulme, 2012 for a fine analysis). Most of the worlds scientific academies now accept that they have to engage in a very different approach to credibility, though this is by no means a universal sentiment. This involves discussion with a range of political, commercial, and community interests, for more attention to communicating uncertainties, much more creative use of scenarios and storytelling, and a genuine predisposition to accommodate to contradictory interpretations. These shifts, which have rarely proven easy to accommodate, have paved the way for sustainability science. And this is now the focus of global interest and scientific renaissance.

Sustainability science is continually evolving within the prisms of dilemma covered in this paper above. It takes as its overarching theme a form of economy which acknowledges ecosystems as both encouragement and impediment. It seeks to enable societies to address their humanness of responsibility, empathy, and compassion. It strives for measures of wellbeing and resilience, geared to greater social justice and decency of living. What could be special about sustainability science is that it searches its way through processes of conversation, listening, and teaching. It is based on the mutuality of companionship. Companions learn consciously and innately how to support each other through transitions with no clear end. They progress through recognizing signposts which give them strength, courage, and determination to continue. They may be surrounded by hostility, but more likely by incomprehension. So they need to learn to communicate through humility, empathy, and courtesy, winning new friends by exemplifying their common purpose and pleasing destiny. We shall see below that these qualities are part of the hallmarks of wellbeing. Indeed unless wellbeing is championed, sustainability science may not survive.

The theoretical perspectives of ambivalence, of searching for identities, of exploring and re-defining power relations are all relevant here. Indeed, higher education generally still has to grasp the significance of sustainability science. One reason here is that the very notion of science carries its cultural interpretative baggage, as stated by Walker and Shove (2012). We shall see below that the promotion of education and learning for sustainability is being stalled by conceptions of science rooted in past paradigms. Knowledge for sustainability may cause less offence (see International Social Science Council 2013, which addresses this theme in a number of its contributions).

Sustainability science has a long and difficult birth. Hal Mooney and his colleagues (2012) comprehensively chart this history. Three aspects stand out. One is the persistence of the international science community, led by the International Council for Science (misleadingly retaining its original acronym: ICSU), working together to bridge the natural and social sciences in addressing global environmental change for the betterment of people and the planet. Conference after conference inched their meandering ways toward this goal. This costly endeavour was persistently supported by the International Group of Funding Agencies for Global Environmental Change (IGFA: the bigger spending part of which is called The Belmont Forum).

A second is the interconnection with the UN global sustainability conferences and the shifting institutional architecture of the creaking UN policy guiding machinery. This has tied advances in sustainability science to creative movement in global measures geared to sustainable development goals. The third is the remarkable openness of the modern science community to embrace the companionship qualities of a listening and experimental approach to learning though example and emblematic casework. The emphasis shifted to applied usage, to a wide variety of stakeholder parties, including the normally marginalized poor and the politically weak, the quiet shadows of the unrepresented. And the notion of defining problems, where agreement is always tenuous, is giving way to a much more positive and optimistic framing of redefining problems as possible solutions.

The outcome is the current initiative under the title Future Earth: research for global sustainability. This is a ten year programme involving all of the major international science communities, UNESCO, UNEP, and the UN Universities, operating under the rather grand umbrella name of Science and Technology Alliance for Global Sustainability (Future Earth Transition Team, 2012: http://www.futureearth.info). This will engage scientists, but especially young scientists to work across disciplines, countries, and cultures. It will address solutions, not problems. It will explicitly incorporate the wide range of social sciences and humanities, heretofore not so directly engaged in action research of this kind. It will seek out research companions in business, government, and civil society for joint understanding and cooperation. This time, perhaps conscious of the dangers of the Anthropocene, the whole science community is more united to make this vision work.

These are early days. Many challenges remain to be tackled. These apply to the procedures for defining the career paths of all scientists but especially young scientists, where it is still difficult to tackle action orientated research through long running inclusive stakeholder involvement. There are also blockages in funding, in publication, in defining successful impacts and achievements, and in creating perforated walls in universities to enable action research to take place in the streets and fields where the sustainability transition ultimately has to emerge. This in turn opens up the difficult arenas of changing human habits and cultural norms, hugely entrenched vested corporate interests, and deeply engrained political outlooks. These massive blockages were emphasized in the second prism of dilemmas introduced above. Convulsive shifts in these critical domains will be neither easy nor speedy. And even excellent sustainability science on its own will not achieve this vital transition. It will take time for sustainability scientists to be understood and appreciated for the betterment of wide and long which they seek to create.

The theoretical perspectives introduced above make a strong point of probing the troubling relationships between transformative challenges and the buttresses of the established order. In the new learning for sustainability (Ryan and Tilbury, 2013; Higher Education Academy, 2014) claims are forcefully made for greater off-campus learning, for the use of social media as a research base, and for more reflective and crucial approaches to interpreting existing power relations. Yet in the fields of higher education the very innovations to learning are subtly being challenged by mindsets of the established order, particularly around disciplinary competence and supposedly value-free research methods, inhibiting the transitions to a knowledge base for sustainability transitions, which should be the hallmark of Future Earth.

A SECOND ANTIDOTE: INTRODUCING WELLBEING AS A BASIS FOR REDEFINING SUSTAINABILITY

Wellbeing is a touchstone for three debates:

1. The clear need nowadays for a more comprehensive measure of economic and social betterment than just gross domestic product (GDP) (for a fine review see Van den Bergh, 2007; Legatum Institute, 2014). Such a move is becoming vital for better policymaking. This will require a set of measures which emphasize social enrichment, a sense of being fairly treated, training to enhance personal capabilities, providing security and amenity in local neighbourhoods, and enrichment of community connectedness. Such measures should be offered in parallel with the more familiar wealth, jobs, and economic performance items associated with established GDP accounts.

2. A means for capturing the qualities of living which many people cherish and which they fear are being lost for lack of attention and concern in the drive to reactivate conventional economic growth. This picks up both research and opinion poll data which indicate that many citizens are looking for a different form of living, with more attention to the quality of their locality, and to remaining mentally and physically healthy as the economy fails to thrive along conventional measures (see Ipsos-Mori, 2005).

3. The basis for a whole new approach to creating an equitable and just society which provides everyone with the capabilities, the confidence, and the prospects for their flourishing as both creative individuals and responsible citizens. This is nothing short of a new social and political engagement. There is a lot more to wellbeing than just happiness (see Hawksworth, et al., 2012; IPPR, 2012).

At stake is something of a struggle to grasp the basis for steering the economy toward enhancing a more robust and appreciated natural world giving more recognition to social investment and enterprise as a basis for creating secure prosperity. Also relevant are the themes of social cohesion (or breakdown), of equality of income and opportunity (or growing divide), and of social mobility and aspiration (or stagnation and depression).

ON MEASURING WELLBEING

A report by Forward Scotland (2008), which considered many approaches to wellbeing indicators including a nationwide survey, suggests 18 different measures for tackling wellbeing indicators. These relate to six prime variables and three domains (individual, community, and society). What follows are the six variables with the three domains indicated in brackets. The full report (Forward Scotland, 2008, pp. 25-44) provides much detail of these indicators, probably the most comprehensive in the literature.

Family and immediate social relationships (satisfaction with immediate family connections, general trust, community involvement);

Work and income (job satisfaction, work security, feelings about the health of the economy);

Mental and physical health (self-reported health, satisfaction with health and care services, chances of living beyond 80);

Wider social context (housing, satisfaction with neighbourhood, overall feelings about governance and democracy);

Environmental quality (especially noise, interior and exterior air quality, litter, neighbourhood dreariness, access to open nature, feelings about the habitability of the future);

Education and training (satisfaction with own education, with the education and training for children, and for education for bettering society as a whole).

There is a strong case for improving self-reported measures for all of these six fields and for each of the three domains. However, self-reporting has its dangers. Not all wellbeing measures can be self-reported (for example air quality, noise) and on-line reporting disfavours those with no access to the internet (who may be the most in need of wellbeing reporting). The Scots team pleaded for better international validation. That is provided in part by a companion report (Wallace and Schmuecker, 2012, p. 9) which selects a variety of case studies from Canada, the US, France, and the UK. The selection by Forward Scotland suggests that work could be done to establish on-line self-reporting both in everyday experience (work, healthcare, schools, and higher education and training) and during particular occasions, say during local and national elections and the census. The Forward Scotland report also asked for better measures of psychological aspects of leisure, freedom, identity, and connectedness.

Taking this further, Dolan et al. (2006) suggest six ways for putting wellbeing measures into effect, depending on whether the frame is evaluating a policy measure (the first three) or discovering inner feelings (the last two). These are:

Preference measures around income preferences and spending set in established welfare economic frames;

Objective lists commonly thought to be proxies for wellbeing such as material comforts and freedom of expression and the exercise of choice, but building on preferences;

Functioning accounts of relationships and overall meaning of social contacts and trust;

Hedonic accounts of feelings over a given period of recent time (favoured by ONS);

Evaluative accounts of individuals overall feelings about life in general.

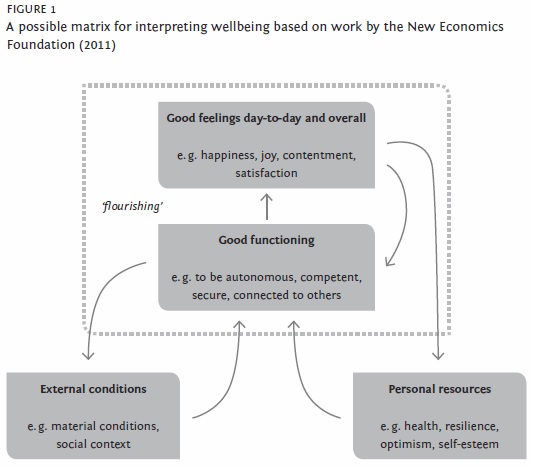

This work has led to a core diagram which links the various dimensions of wellbeing as developed by the Centre for Wellbeing (2011) at the New Economics Foundation.

WELLBEING AS SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION

Much of the interpretation of this diagram follows from enlarging the two lists above. External conditions relate to housing and home, to work and career progress, to local amenities and neighbourly trust, to walkability (a measure of community safety and local amenity), and to involvement in active voluntary organizations. Personal resources apply overall to health and self-respect, with close links to mental strength (or mental weakness, which is related to feelings of worthlessness, rejection, and despair) and to learned optimism (seeing the world as positive opportunities), as well as good cognitive capacities in grasping meanings and associations from day to day experiences and social encounters. These personal qualities spill over into good functioning. This relates to feelings of a good life overall (using the word from Aristotle: eudaimonia). The list of social psychological features normally associated with good functioning includes self-acceptance, positive relations with others, personal growth, purpose in life, environmental mastery, and autonomy. The top box is the apex of the wellbeing process, the themes sought by the ONS in its surveys. These apply to feelings of contentment, happiness, and positive judgements about life in general. In essence these feelings relate to the combination of the other factors, experiences and personality traits in the connected loops.

Most important are the feedback loops (upper right arrows) arising from positive feelings. One of these relates to better control of mental and physical strength allowing for a sense of coping and resilience and autonomy when facing difficult circumstances (loss of a job, changes in neighbourhood social composition). The other loop applies to developing both the personal qualities of commitment and staying power as well as an improved capability for improving external conditions (such as volunteering and joining supportive community organizations). In this important sense the ONS data relate to windows for further discovery. They are not end points in the search for a group of wellbeing measures. What are of importance are the qualities of the three boxes and the power of their interrelations.

Ultimately what we are seeking in wellbeing is less to do with happiness or even contentment. It is much more to do with flourishing, with the capacity to cope with change of whatever kind and to help others to cope better. It may follow that good government, namely government which follows the practices of integrity, or responsiveness, of sharing and exploring together, and of responsible devolution will be the government of wellbeing.

Ultimately the promotion of wellbeing requires five drivers as summarized below, but extended here, offered in the report by IPPR North and the Carnegie Trust (Wallace and Schmuecker, 2012, pp. 41-3). These are:

Wellbeing measures should be based on full civic involvement and commitment across the nation, devolved, regionally and locally. They should give a sense of direction for betterment for all and for improving the flourishing capabilities of the disadvantaged in particular. Wellbeing accounts should be regular and important events which lie directly alongside GDP accounts;

Leadership throughout governance generally is critical as this process will require changes in policy, in policy making, and in policy delivery, which will demand conviction and openness of mind. Leadership should come throughout the whole of civil society and be endorsed as such;

Coalitions of support need to be built right across the nation. This is not a process to be run from the top. It requires painstaking commitment and understanding and should be built into all elements of education;

The presentation of wellbeing indicators needs to be clear and intelligible and exciting. This will demand the utmost from statisticians and graphic designers working with the people most directly affected;

Civil society as well as community foundations should directly drive wellbeing research and findings and ensure through competent arrangements their incorporation into policy. It is important that non-monetary values are treated as such as they sit alongside monetary based measures and often supersede them in the importance which they are given by citizens across the fabrics of society. The active cooperation and engagement by people in the delivery of what is best for them through mutual responsibility and efficacy will improve the public provision of services through a variety of pathways. In this important sense a nation should be guided by a Council of Economic and Wellbeing Advisors and not just a Council of Economic Advisors.

CRITIQUES OF WELLBEING

The Centre for Confidence and Wellbeing (2012) challenges these seemingly too simplistic constructions of the notion of wellbeing. They see these as being too naïve in the many-sidedness of modern cultures. Furthermore, they stress the impact of vulnerability and inability to make choices for many disadvantaged people and social groupings, for whom wellbeing is a heavily nuanced concept. They also point to the overdependence of psychological measures on what is much more a longitudinal social framing. From the perspective of this paper there is also a very real danger that wellbeing provides a loose antidote to the dominance of gross domestic product as a guide to economic performance, and hence could offer a parallel social account for measuring betterment. Yet as we have seen in the reviews of transition societies, there remains a deep ambiguity over what constitutes betterment. And current practices of planning strike against improving even fairly basic interpretations of betterment (Rydin, 2013). Once again we need to evolve in our approaches to these antidotes, constantly being aware of opportunities and blockages.

A THIRD ANTIDOTE: SOCIAL INVESTMENT

One logical outcome of wellbeing is the current interest in social investment. This is of two kinds. One is essentially charitable giving in which investors place funds in schemes which are designed to better people and society who are other- wise disadvantaged. The other is to offer schemes of incentives and support to those who are a cost to themselves and to society more generally, so that they take on responsibility and avoid future financial burdens of the public purse.

The first form of charitable investment is the driver behind the social investment bank (Cabinet Office, 2011). The aim here is to draw funds from dormant bank accounts and use these to support social enterprises and charities which aim to improve the training and self-worth of young people and to give them the basis for creating their own businesses in social enterprise marketing. Ideally, the outcome is not only a whole new form of gainful employment, based on the fundamentals of wellbeing, it is also a way of capturing the imagination, innovation, passions, and skills flexibility of modern youth, particularly with their facility in social networking and information technology more generally.

It is too early in the development of the social investment bank to assess its overall value. But the many barriers expounded in the introductory part of this paper seem to be suffocating it. There are no spare funds in dormant accounts as many of the most relevant are being swept away to tax havens; few social initiatives can work for long periods if the charitable sphere is contracting; most social enterprises depend on a tax holiday for at least a start-up period, which is not forthcoming in an age where tax incomes are vital for the resurrection of investment in the conventional economy. And there is a grumbling amongst market fundamentalists that this is not real value but some kind of charity of a kind more commonly found in Victorian times. Consequently social investment will require a concerted effort from businesses which are either strapped for cash as the banks restrict and channel lending for measurable gains, or which are really only prepared to pay lip service to what they regard as government responsibility. Alternatively such investments will need to be fuelled by a new set of charitable not-for-profit trusts specifically set up to encourage the wealthy to divert some of their otherwise taxable inheritance into the betterment of the coming generation. This would require mighty leadership and careful handling of public relations by finance ministries and central government. But it does have promise as a basis for transferring wealth from the fortunate post war boom generation to their struggling offspring (see Willetts, 2009).

The second form of social investment is more promising. This depends on the intervention in the lives and consumption habits of people who are proving a cost to themselves (alcoholism, obesity, diabetes type 2, self-harm, early and unwished pregnancy, and substance abuse). All this tends to result in expenditures to various other parties, such as other insurance contributors, or to health authorities. For example, in the UK the cost of obesity alone is estimated to be over £5 billion annually and the cost of treating depression over £4 billion per year (UK Department of Health, 2011).

The Foresight study on mental health and wellbeing (2008) discovered a mental dip amongst 12 to 15 year olds (especially boys). This is a function of poor parental guidance, bullying, peer pressure, and loss of self-esteem. This can lead to anti-social behaviour which disrupts learning, as well as breeding gang cultures and street violence. Often absenteeism from school is associated with such symptoms, which in turn adds to the likelihood of poor educational performance and unemployability. The Foresight report (2008, p. 21) estimates that as many as half of young adults from disadvantaged communities do not have the transferrable skills to hold down a job.

Mental disorders in the UK affect about 16% of adults and about 10% of children. Many are afflicted by the scourges of poverty, of un-love, of abuse, and of unhealthy habits. All could be enhanced by early intervention to give them wellbeing in the senses outlined above. What is missing are the mechanisms to encourage this opportunity and to test out that it leads to a better overall future citizenry as well as a lower maintenance society.

But social investment is not easy to promote even when there are potential savings in lost social capital and diminished wellbeing in the pipeline. Finance ministries hate to invest in schemes where the potential savings are not proven. In the UK there is a huge row between schemes for rewarding mentoring of young offenders which pay the participating charities on the basis of much lower reoffending rates over a five year period. At present some 47% of youth prisoners with fewer than six months of incarceration reoffend. Each costs some 20,000 Euros on an annual basis to look after. The Treasury is willing to test out this scheme on the basis that the mentoring leads to improved indicators of wellbeing, but the publically funded Probation Service, sensing a loss of their income base and the displacement of career professionalism in this sensitive social area, is strongly opposed.

There is as yet no clear evidence of the effectiveness of particular schemes for volunteering or mentoring or social enterprise creation (where young people may form not-for-profit businesses to undertake such tasks). Undertaking research where such mechanisms aimed particularly at the hard to reach young adults suffering mental depression, drugs and alcohol abuse, early unwanted pregnancies, and obesity/diabetes type 2, is virtually untested in a framework of wellbeing enhancement. Without this research it is unlikely that there will be any revolution in the troubled arena of social investment. There are no clear mechanisms for delivering such uncertain outcomes unless the fabric of social order clearly becomes irreparably torn. And then it will be too late. What we must keep in our minds is the lingering overall generosity still built into most of the public, a generosity favouring a better deal for the coming generation and a fairer distribution of wealth (see Hawksworth, et al., 2012; Willetts, 2009). This is also the overall lesson from recent wellbeing research.

RETURNING TO THE PRISMS OF DILEMMAS

We face a troubled decade to come. The effects of continuing sluggish growth, uncertainty over the future integrity of the Euro, continuing reduction of household incomes, and constantly failing aspirations, as well as underinvestment in human and capital infrastructure could give rise to a deeply ill-being society. The need to address the incorporation of wellbeing as a central tenet of sustainability, bearing in mind the vital need to address simultaneously planetary boundaries and rising inequalities, is becoming urgent. There is scope for transition. It is happening in the streets and fields of the unexplored niches of heartening sustainability transitions (see Flanigan and Weatherall, 2013 for some helpful examples). But these are ephemeral and easily abandoned if the external conditions for their flourishing are not made compatible. All too often the unhelpful setting of unsupportive public and financial organizations suffocate such innovative transitions. Their value for sustainability and their experiences of frustration and obfuscation need to be carefully studied.

This transition will not be easy. One glaring need is to reduce the devastating consequences of inequality and blocked life chances for over a third of most modern western societies. A significant change of culture will be required. For example, we may have adapt to a three day working week, much more family and intergenerational sharing of care and support, self-built and affordable homes, and widespread formal and informal mentoring (see Hawksworth, et al., 2012). Cultural norms rarely shift quickly, and even less probable is long-term sustained transformation. Yet arguably we have too little leeway for even a decade of waiting. There are many reasons for this friction of cultural shift.

Habits dominate. Yet habits are tricky to identify and to alter. Habits are accustomed and comforting behaviour, and help to identify social status and acceptance of peer groups. Much of consumption of food, water, energy, and carbon (as fuel and as embedded in consumables) is driven by habit;

Powerful interests block any change which disfavours them. This is evident in the financial services sector which seems to have emerged from its collectively induced crisis as politically and economically strong as before. Lobbying by overwhelming vested interests in the main sectors of energy and food and chemicals is almost unconquerable even in the face of courageous non-governmental group protest (see for example Carbon Tracker, 2012)

Governments may not be popular, but they do control social initiatives and create regulatory and financial hurdles which are hard for well-meaning community based organizations to overcome on their own initiative. Some of these provisions are helpful for the pursuit of wellbeing. But the savage slashing of charitable funding from most governments is hurting the weak and limiting the historic support base of many well-meaning community based initiatives

Following from this, it is often difficult for any significant individual or community led transition initiatives to expand or even to flourish in a setting where government led rules and financing arrangements are often working at cross purposes and confound sincere action. This is why so much emphasis needs to be placed on training and experience for emphasizing with transition activities at the local scale.

Collective action is arduous to mobilize. It takes time, effort, and leadership along with persistence and commitment to triumph. The key ingredient is leadership. This is in short supply unless the schools breed genuine game changers, and political leaders are willing to work over the long haul with community aspirations

Now is the time for the social sciences to grasp the nettle. There is a golden opportunity for research to identify the scope for incorporating wellbeing into national performance frameworks as the Scots are proposing. There is also a hole in the work of social investment performance and viability as indicated in the discussion above. To explore new forms of not-for-profit wellbeing trusts, especially at the regional and local scales, is of the utmost importance. Most of all, there is a need for leadership within the academic community along with like-minded colleagues in government, civil society, and in business, as is being proposed for Future Earth.

The challenge here is profound. We do not really know how existing institutionalized cultures of regulation and steering, as well as comfortable but dysfunctional codes of practice, die or are replaced. We also do not know how community-based movements can coalesce through responsive and innovative institutional cultures of progressive transformation. Here is the great opportunity for the knowledges and learning processes of sustainability which underpin Future Earth yet which still face the resistances of the very academic cultures which they seek to replace. The most likely outcomes lie in the combination of the persistence of the prisms of dilemmas, which will lead to social convulsion and personal pain, and new political confrontations. These include: immigration, household budgetary squeeze, discontent with the fundamental moral unfairness of stretching inequality, and failures of international and national governments to contain irresistible moves toward sub-national cultural and landscape identity formation and more autonomous governance. This pernicious combination might well unleash examination of the deficts in understanding and in societal progression which to date have eluded us.

REFERENCES

ACTION AID (2012), Under the Influence: Exposing undue Corporate Influence Over Policy Making at the World Trade Organization, London, Action Aid. [ Links ]

AVELINO, F. & ROTMANS, J. (2010), Power in transition: an interdisciplinary framework to study power in relation to structural change. European Journal of Social Theory, 12 (4), pp. 543-569. [ Links ]

BELL, D.;N.;F. & BLANCHFLOWER, D. (2009), What Should be Done about Rising Unemployment in the UK?, Stirling, Scotland, The University of Stirling. [ Links ]

BROUGHTON, A. (2012), The Institute for Employment Studies (http://www.employment-studies.co.uk/press/10_12.php). [ Links ]

CABINET OFFICE (2011), Growing the Social Investment Market: a Vision and a Strategy, London, Cabinet Office. [ Links ]

CARBON TRACKER (2012), The Carbon Bubble, London, Carbon Tracker. [ Links ]

CENTRE FOR CONFIDENCE AND WELLBEING (2012), Critique of Flourishing by Martin Seligman, London, Centre for Confidence and Wellbeing. [ Links ]

DOLAN, P., PEASGPOOD, T., & WHITE, M. (2006), Review of Research on the Influences on Personal Well-being and Application to Policy Making, London, Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. [ Links ]

ENVIRONMENT AUDIT COMMITTEE (2012), A Green Economy, London, Parliamentary Environmental Audit Select Committee. [ Links ]

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2014a), Executive Summary of the Fiscal Sustainability Report, Brussels, pp. 1-5. [ Links ]

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2014b), EU Measures to Tackle Youth Unemployment, Brussels. [ Links ]

FORESIGHT (2008), Mental Capital and Wellbeing: Making the Most of Ourselves in the 21st Century, London, Government Office of Business. [ Links ]

FLANIGAN, B. & WEATHERALL, D. (2013), Sustainable Consumption in the UK: a Selection of Case Studies, London, Institute of Public Policy Research. [ Links ]

FORWARD SCOTLAND/SCOTTISH COUNCIL FOUNDATION (2008), A Wellbeing Framework for Scotland: a Better Way for Measuring Societys progress in the 21st century, Edinburgh, Forward Scotland. [ Links ]

FUTURE EARTH TRANSITION TEAM (2012), A Framework for Research, Paris, International Science Union. [ Links ]

GEO 5 (2012), Environment for the Future We Want, Nairobi, UN Environnent Programme. [ Links ]

HAWKSWORTH, J., JONES, N.;C., & USHER, K. (2012), Good Growth, London, Demos/PwC. [ Links ]

HENRY, J.;S. (2012), The Price of Offshore Revisited, London, Tax Justice Network. [ Links ]

HIGHER EDUCATION ACADEMY (2014), Education for Sustainable Development: Guidance for UK Higher Education Providers, Bristol, The Higher Education Academy. [ Links ]

HULME, M. (2012), Why we Disagree about Climate Change, Cambridge , Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

INTERNATIONAL FORUM ON GLOBALIZATION (2005), Report on Corporate Power, New York. [ Links ]

INTERNATIONAL SOCIAL SCIENCE COUNCIL (2013), World Social Science Report: Changing Global Environments, Paris. [ Links ]

IPSOS-MORI (2005), Liveability-Where are we Now?, London, Ipsos-Mori. [ Links ]

JASANOFF, S. (2012), Science and Reason, London, Routledge. [ Links ]

JOYCE, R. (2012), The Decline in Household Income over Recession and Austerity, London, Institute of Fiscal Studies. [ Links ]

LEGATUM INSTITUTE (2014), Wellbeing and Public Policy, London. [ Links ]

MAKAWANA, R. (2006), Share the Worlds Resources, New York. [ Links ]

MARKAND, J., RAVEN, R., & TRUFFER, B. (2012), Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Research Policy, 41, pp. 955-967. [ Links ]

MOONEY, H., DURAIAPPUH, A., & LARIGUADERIE, A. (2012), Evolution of natural and social science research interactions in global environmental change programs. Proceedings of the American Academy of Sciences (http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1107484110). [ Links ]

NEW ECONOMICS FOUNDATION (2011), Measuring our Progress: the Power of Well-being, London, New Economics Foundation. [ Links ]

NORDHAUS, T., SCHELLENBURGER, M., & BLOMQVIST, L. (2012), The Planetary Boundaries Hypothesis: a Review of the Evidence, Washington, DC, Breakthrough Institute. [ Links ]

OFFICE OF BUDGET RESPONSIBILITY (2012), Fiscal Sustainability Report 2012, London, OBR. [ Links ]

PRETTY, J. (2013), The consumption of a finite planet: well-being, convergence, divergence and the nascent green economy. Environment and Resource Economics, DOI 10.1007/s10640-013-9680-9. [ Links ]

ROCKSTROM, J. et al. (2009), Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461, pp. 472-475. [ Links ]

ROCKSTROM, J. & KLUM, M. (2012), The Human Quest: Prospering within Planetary Boundaries, Stockholm, Langenskiolds. [ Links ]

RYAN, A. & TILBURY, D. (2013), Flexible Pedagogies: New Pedagogical Ideas, Bristol, The Higher Education Academy. [ Links ]

RYDIN, Y. (2013), The Future of Planning: Beyond Growth Dependence, Bristol, Polity Press. [ Links ]

SHOVE, E. & WALKER, G. (2007), CAUTION! Transitions ahead: politics, practice, and sustainable transition management, Environment and Planning A, 39, pp. 763-770. [ Links ]

THE ECONOMIST (2012), Special report: global inequality, London, The Economist, 13th October. [ Links ]

THE ECONOMIST (2013), Storm survivors: a special report on offshore finance, London, The Economist 17th February. [ Links ]

THE ECONOMIST (2013a), Generation jobless, 27th April, pp. 69-61. [ Links ]

THE PRINCES TRUST (2012), The Undiscovered Generation, London, The Princes Trust. [ Links ]

UK DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH (2011), Obesity, London. [ Links ]

UN HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT (2005), Sustainability and Equity: a Better Future for All, New York, UN Development Programme. [ Links ]

UN (2005), Report on the Worlds Social Situation, New York, UN. [ Links ]

VAN DEN BERGH, J.;C.;J.;M. (2007), Abolishing GDP, Amsterdam, Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper, Free University. [ Links ]

WALKER, G. & SHOVE, E. (2011), Ambivalence, sustainability and the governance of socio-technical transitions. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 9 (3-4), pp. 213-225. [ Links ]

WALLACE, J. & SCHMEUCKER, K. (2012), Shifting the Dial: from Wellbeing Measures to Policy Practice, Dunfermiline, Scotland, IPPR North and Carnegie Trust. [ Links ]

WILLETTS, D. (2009), The Pinch: How the Baby Boomers Took Their Childrens Future and Why They Should Give it Back, London, Atlantic Books. [ Links ]