Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.201 Lisboa out. 2011

The Spanish extreme right and the internet

Manuela Caiani*; Linda Parenti**

* Institute for Advanced Studies, Department of Political Science Stumpergasse, 56 A, 1060 Vienna, Austria. e-mail: caiani@ihs.ac.at

** Università degli studi di Firenze, via Delle Pandette, 21, 50127 Firenze, Italia. e-mail: lindaparenti@gmail.com

Abstract

This article investigates the potential role of the internet for Spanish extremist right-wing organizations for their contacts (at the national as well as at the international level), the promotion of a collective identity and their mobilization. To address this issue, it employs a combination of quantitative and qualitative research techniques. A social network analysis, based on online links between about 90 Spanish extreme right organizations, aims to investigate the organizational (online) structure of the right-wing Spanish milieu, and a content analysis of right wing web sites to grasp the degree and forms of their internets usage for various goals. The analysis focuses on different types of Spanish extreme right organizations (from political parties to skinhead and cultural groups). The results are interpreted against the off line political and cultural setting of opportunities and constraints offered by the country.

Keywords:Extreme right movements; social networks; politics on the internet; Spain.

A extrema-direita espanhola e a internet

Resumo

O artigo investiga o papel potencial da internet para as organizações espanholas de extrema-direita, tendo em vista o estabelecimento de contactos (a nível nacional e internacional), a promoção da identidade colectiva e a mobilização. Para analisar este tema, o artigo combina a metodologia qualitativa e quantitativa. A análise das redes sociais, baseada nas ligações online de cerca de 90 organizações espanholas de extrema-direita, tem o intuito de analisar a estrutura organizacional (online) da extrema-direita espanhola e o conteúdo dos sítios na internet para compreender o grau e a forma da utilização deste canal para alcançar os seus objectivos. A análise debruça-se sobre diferentes tipos de organizações espanholas de extrema-direita (desde os partidos políticos aos skinheads, passando pelos grupos culturais). Os resultados foram interpretados em confronto com as oportunidades e limitações off line do cenário político e cultural do país.

Palavras-chave: Movimentos de extrema-direita; redes sociais; política na internet; Espanha.

Introduction1

The Internet is an increasingly powerful tool for politics, including radical politics. Traditionally considered as an instrument of democracy and global thinking, recent studies indicate that extremists use the web to spread propaganda, rally supporters, preach to the unconverted, and as a means of intimidating political adversaries (ADL, 20012). If up until now, research on the Internet as a channel (and arena) of political communication and mobilization has focused mainly on left-wing social movements (e.g., Zapata, NoGlobals) (Garret, 2006), recent scholars have started to pay attention to right-wing extremist groups and the Internet, as well (Atton, 2006; Chau and Xu, 2006).

In Europe hundreds of websites run by neo-Nazi and skinhead organizations have been identified (De Koster and Houtman, 2008) and European institutions have increasingly expressed interest (and concern) regarding this growing phenomenon (TE-SAT Report, 2007, p. 15). Although less prominent than in Northern European countries (e.g., Sweden, Norway, and Germany; Caldiron, 2001, p. 355), this phenomenon is also present in Spain. A recent European study found that Spanish extreme-right groups use the Internet to create web pages, blogs, forums, and chats (Informe Raxen, 2008), and 2006 saw the first case of a conviction for the establishment of an extreme right web site (Informe Raxen, 2007, p. 23). This trend was confirmed in the last (2007) local elections when the extreme-right party, Platform for Catalonia, strongly and successfully relied on the Internet to recruit members and voters (Hernández, 2010).

Research emphasizes that extreme-right organizations use the Internet for several different functions. Studies have found that the Internet is used for disseminating propaganda, rallying supporters and inciting violence (Whine, 2000 and ADL, 2001). It is argued that the web, boundless, difficult to be controlled, in a state of continuous change, is the ideal place for those at the boundaries between legal politics and illegal activities (Fasanella and Grippo, 2009, p. 156). Focusing on US groups, Zhou and colleagues (2005) demonstrated that extreme-right organizations use the Internet in order to facilitate recruitment, to reach a global audience, and for facilitating contacts with other right-wing organizations (De Koster and Houtman, 2008). Research on social movements underscores the capacity of the Internet to generate collective identities, since it favors the exchange of resources and information, and might thereby create solidarity and sharing objectives (della Porta and Mosca, 2006a, p. 538). Additionally, studies on violent radicalization stress that isolated individual consumers can find a common identity through extreme-right websites, convincing themselves that they are not alone, but instead part of a community, if only a virtual one (Post, 2005). Finally, attention is drawn to the role played by this new medium in helping mobilization and the development of transnational contacts, organizations, and protest campaigns (Chase-Dunn and Boswell, 2002; Petit, 2004; Bennett, 2003).

Existing studies on the Internet and the extreme right usually concentrate on the U.S. case (see Burris et al., 2000; Levin, 2002). In rarer instances attention is given to this phenomenon in Europe (the exception being the use of the Internet during electoral campaigns by right-wing political parties, for example Margolis et al., 1999; Cunha et al., 2003; Trechsel et al., 2003, Ackland and Gibson, 2004), especially concerning countries where the extreme right is traditionally weak and less violent, such as in Spain. This article contributes to filling this gap.

Studying the use of the Internet in Spain seems to be a particularly interesting case, as extremist right-wing forces are considered to be weaker there than in other European counties (Carter, 2005, pp. 4-5; Norris, 2005, p. 41), in terms of both electoral results and social acceptance (Casals, 1999; Rodríguez, 2006; Chibber and Torcal, 1997). The extreme-right party spectrum is composed of three main political parties (the Falangistas-Falangists, the Frente Naciónal-National Front, and the Fuerza Nueva-New Force), and many other tiny parties active only at a local level (Carter, 2005, pp. 3-5; Casals, 2001). Moreover, these parties have attracted minimal popular support in the last decade (Norris, 2005, p. 65), thus offering very few institutional channels of access to the political system for the Spanish extreme right.3

It has been argued that this failure is related to the inability of these political forces to create a stable organizational structure and ideology, and to develop a clear anti-democratic and anti-parliamentary program (Casals, 1999). The youth sub-cultural milieu, although successful in terms of social penetration, suffers several internal divisions (ibid.). Besides organizational limitations, observers also point out the ideological backwardness of the Spanish extreme right, which failed to develop a modern right-wing political program following the 1970s, and has in this way progressively lost touch with its social and electoral base (Casals, 1999; Rodríguez, 1999).

However (or perhaps due to this historical weakness), the Internet could be considered as a new and powerful alternative political arena for the Spanish extreme right to embrace in order to raise its profile. A question therefore arises: is the current Spanish extreme right able to face up to the challenges of modernity and to adopt new instruments of practicing politics such as the Internet? This study will help us to shed light on this important issue. Although the larger project of which this article is part includes six European countries, herein we will draw on data for the Spanish case only. However, we will often compare these data with the general trends regarding Internet use that have emerged in the other European countries (for Italy see also Caiani and Parenti, 2009) in order to draw attention to similarities and differences.

Combining a social network analysis (SNA) based on online links between organizations, with a formalized content analysis of right-wing extremist web sites, the current research investigates the role of the Internet for the extreme-right organizations in Spain with a view to organizational contacts (at the national as well as at international level), identity formation, and mobilization. The analysis includes political parties and non-party organizations, even encompassing violent groups (for a total of 90 groups). It centers on the following empirical questions: To what extent and in which forms do Spanish extreme-right organizations use the Internet as a tool for information and communication with the potential audience and to encourage mobilization? How and to what extent do right-wing extremist groups use the Internet for creating a sense of community among the groups adherents? To what extent do they rely on the Internet to build contacts with other similar groups at the national and international level?

In order to empirically investigate these issues, through social network analysis, by focusing on web links between right-wing websites and considering them as ties of affinity, communication, or potential coordination (Burris et al., 2000), we first examine the structural characteristics of the Spanish extreme-right (online) community. Emphasis will be also placed on the question of whether the Internet is used in order to build a cyber community that transcends national boundaries. Second, focusing on the content of the political web communication employed by Spanish extreme-right organizations, we explore the forms and degree of the Internets use for diffusion of propaganda, promotion of virtual communities, debate, and mobilization. The various specificities of the Spanish extreme rights Internet use are analyzed, seeking similarities and differences between different types of right-wing organizations (e.g., political parties vs. skinhead groups). The findings are interpreted against the background of the political and cultural opportunity structure in the sphere of off-line communications.

Methods and data

In order to identify all Spanish extreme right organizations with a presence on line, we used a snow-ball technique (Qin et al., 2007, p. 75). Using a variety of sources (e.g., watchdog organizations, governmental reports), we first identified the most important and well-known Spanish extreme-right organizations and their respective URLs. Then, starting from these and focusing exclusively on friend links that were explicitly indicated by these organizations (assuming that these can be considered proxies for affinity relations and a measure of closeness between the organizations, Burris et al., 2000), we discovered the websites of minor and less well-known groups (identifying a total of 87 organizational websites)4. We manually codified the relational patterns between them to serve as the basis for the SNA. In the second part of the study, we conducted a web content analysis on a reduced sample of about 50 websites, chosen as representative of the different types of extreme-right groups with a web presence5 (see Table 1).

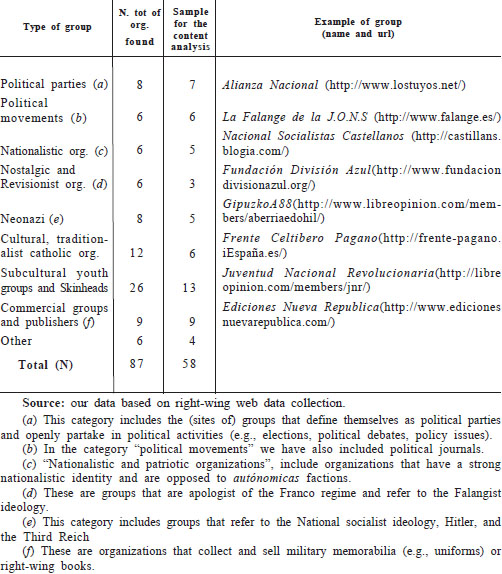

Table 1 - Spanish extreme-right organizations identified, by broader categories

In order to systemically capture the content of the extreme-right websites, we constructed a formalized codebook6, composed of several indicators (and respective lower level indicators) with the aim of measuring the features of the Internet use that we considered to be relevant: (i) the Internet for enhancing groups communication and identity (with variables capturing if and to what extent the group promotes web interactivity with members and sympathizers; hosts, martyrs, and leaders stories; presentations of the goals and mission of the group; inclusion of hate symbols and banners, see Zhou et al., 2005); (ii) offering information (with variable capturing the presence on the groups website of news reporting, documents from conferences and papers, and bibliographical references, Qin et al., 2007); (iii) organizing mobilization (with variables capturing the use of the web for advertising groups initiatives and for activating the members in online and offline actions, della Porta and Mosca, 2006a); and finally (iv) internationalization (with variables measuring the extent of the use of the web for building bridges with other groups in other countries, namely sharing common symbols and content, and creating on line contacts).

Networking online: the Internet as a tool for national and international contacts?

Do the Spanish extreme-right organizations use the Internet to build contacts either between themselves or internationally? Particular attention is paid in this section to investigating whether the web is used by these organizations to create a cyber community that transcends the nation, as has been demonstrated to be the case for extreme-right groups in many other countries (Genstenferld et al., 2003; Caiani and Parenti, 2009). The overall configuration of the Spanish extreme-right online community (comprising 87 organizations for a total of 356 links, appears to be fragmented and shows little internal cohesion7 (Fig.1).

Figure 1 - The online constellation of the Spanish extreme right (web links)

Indeed, according to our data, the network is characterized by a loose chain of contacts between the Spanish groups, and there are even a number of isolated organizations. The average distance between the organizations, is 2.980, which means that on average the organizations of this network are three nodes (actors) away from each other, and the average degree is 4.650, meaning that the average Spanish extreme-right organization is linked with about five other organizations. Therefore, many actors can only communicate with each other through long paths. Finally, the overall density of the network is 0.05, which means that only 5% of all possible contacts between the organizations are actually activated. Furthermore, three different subgroups of extreme right organizations (distinguished along sectorial cleavages, and not well connected to each other), can be indentified within the Spanish radical-right milieu: the cluster composed of the political parties (in the bottom right part of the graph), the (denser) cluster made up mainly by sub-cultural youth groups (e.g., skinhead and music groups) (in the central upper part of the graph), and the one comprising neo-Nazi, ultra nationalist, and cultural organizations (in the bottom left part of the network). Thus, there are not many contacts (at least virtual), among extreme right organizations belonging to different sectors of the same community. Finally, if political parties are usually important when discussing right-wing extremism (Minkenberg, 1998, p. 50), the situation in Spain is different: the Spanish extreme-right political parties (such as Democracia Naciónal, Frente Naciónal, Alianza Naciónal, La Falange, La Falange Auténtica, and La Falange Española), do not emerge as the most central actors of the network. In the language of SNA this is expressed in the very low levels of incoming links, namely contacts sent by other organizations of the network (in-degree values between 3-5, or even zero).

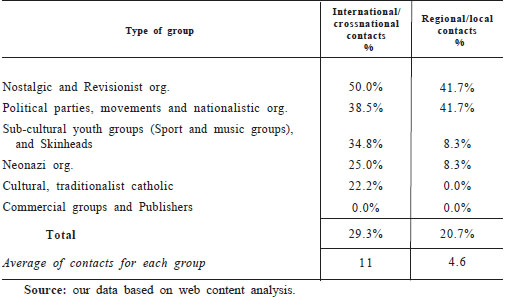

In addition to this internal fragmentation, the Spanish extreme right also emerges on the web as an internationally isolated community, not strongly linked to other European extreme rights, neither in terms of the content of the websites nor in terms of inter-organizational contacts. Focusing on the content, very rarely do Spanish extreme-right organizations make efforts to appeal to an international audience, offering on their websites content in languages other than Spanish (e.g., in English) (occurring in only 10.3% of the cases analyzed, i.e., 6 of 58 groups). Looking at the cross-national and international (online) contacts, only one third of the Spanish extreme-right organizations (29.3%) contain links on their websites to extreme-right groups in other countries or to international federations (e.g., European right-wing political parties) (Table 2). Moreover, it appears that these virtual contacts are not used by the Spanish extreme-right organizations to create cross-sectorial communication (i.e., across different types of extreme-right organizations across the borders of the country), but, on the contrary, they tend to connect mainly to similar organizations in other countries.8

Table 2 - International/Cross-national contacts (online), by type of extreme right organization

On the contrary, since Spanish extreme-right organizations do not appear to be embedded in a transnational right-wing community, one can wonder if they are not mainly characterized by regionalism and a tendency to localization, which has been showed to be a feature of the left-wing Spanish social movements (Jiménez and Calle, 2006, pp. 129-130). Analyzing all the links of the organizations (at the international, national, and local levels), however, it emerges that only 20.7% of them have contacts with local or regional groups, with an average of almost 5 local links for each group. In conclusion, the Spanish extreme right has been shown to be rather poorly connected through the web, at both the international and local levels.

Communication, identity and mobilization through the Web: the missed opportunity of the Spanish extreme right?

Our content analysis of extreme-right websites shows, first of all, that Spanish organizations use the Internet quite frequently for the diffusion of (political and non-political) information to their members and sympathizers. However, it occurs less frequently than we might expect. Indeed, the extent of the use of the Internet for this function is not homogeneous, depending strongly upon the type of extreme-right group being examined and the type of information diffused. Spanish extreme-right organizations often use their websites for news reporting and news coverage (half of the groups analyzed, 50%), repeating news drawn from other media, such as newspapers and TV, as well as for publishing articles, papers, and dossiers (48.3% of the organizations analyzed). Slightly less frequent is the use of the Internet in order to diffuse propaganda (only one third of the organizations analyzed published bibliographical references on their websites). This informative material is varied in nature. It ranges from articles, commentaries, pamphlets, and reports concerning political and social issues, either current or historical (e.g., the Basque country and the requests for autonomy; the fight against the ETA; reports on immigration, etc.)9 to biographies of leaders of the Nazi or Francos period10, and books and works written by intellectuals and founding fathers of Spanish nationalism (e.g., works on Primo de Rivera, Unamuno11). A smaller number of Spanish extreme-right organizations consistently update their websites with information concerning conferences and other current political activities (only 10% of the groups offer documents related to conferences and meetings on their sites).

In order to better understand Spain as a case study, we cite the results of a similar study focused on the Italian extreme right (Caiani and Parenti, 2009), which demonstrates that Spanish right-wing organizations use the Internet to the same (notable) extent as the Italian ones for the information function. However, when we investigate the use of the Internet by Spanish extreme-right organizations to enhance the communication between the group and the potential visitors, a moderate activism of the Spanish extreme right emerges from the analysis. Only one of the 58 websites analyzed offers the help function option, although approximately one third of the sites (31% of cases) provide a search engine. Surprisingly, for groups constantly at risk of being banned, our data show that another third of organizations (32.8%) offer contact information (such as an address, phone number, and fax) on their website, and 80% provide an mail address. On the contrary, the majority of the Spanish organizations do not seem interested in showing their success in terms of audience on their websites: in only 19% of cases (vs. 60.9% of cases for concerning the Italian extremist-right groups) is there a visible counter to record the number of online visitors.

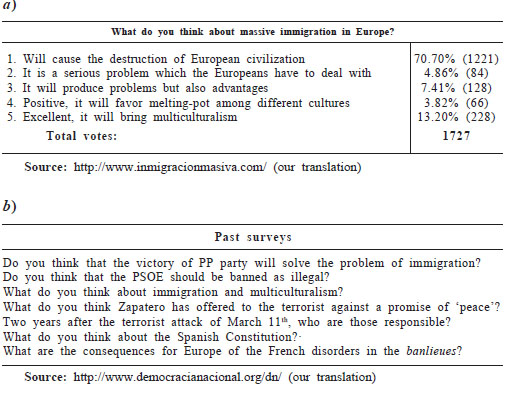

Reinforcing the impression of a moderate use of the web by Spanish right-wing extremist groups for the purpose of communication, we also observe that spaces of debates and web interactivities, such as forums for discussion or chat rooms where right-wing activists and members can meet and exchange their ideas, are not very frequent on the websites of these organizations. In particular, only 10.3% of our sample offer a newsletter on their websites; 19.0% have fora of discussion and/or mailing lists, and even rarer are online chats presented on the extreme-right websites (in 13.8% of cases). The Italian extreme right has appeared to be more prone to use the Internet in order to create virtual spaces of web interactivity and discussion (Caiani and Parenti, 2009). More frequent in the Spanish case is the presence of online surveys and questionnaires (19% of cases). These above all concern current politics and immigration issues, such as those posted on the homepage of the website Inmigración Masiva (Massive Immigration) entitled What do you think about massive immigration in Europe? and on the page of the political party Democracia Naciónal (National Democracy) (see table 3a and 3b). Nevertheless, a more in-depth look at these tools of communication with the audience reveals that they are not arranged for the purpose of a true expression of opinion by the users, but instead they seek to structure opinion in a quite hierarchical way (offering only a few pre-coded options for answers from the visitors).

Table 3 - Examples of online questionnaires on the Spanish extreme-right websites

Concerning mobilization through the web of the members in political activities (either via online or offline political actions, see della Porta and Mosca, 2006a), Spanish extreme-right organizations do not emerge as well-versed in using the Internet for this function. Fewer than a fifth of the organizations analyzed (17.2%) publish on their websites an agenda of their events and initiatives in order to promulgate information on meetings, demonstrations, assemblies, and concerts. Furthermore, in only a very few cases (3.4%) do these groups publish on their websites the agenda of the events and initiatives of another group, suggesting that the Internet is scarcely used by these organizations for reinforcing a sense of solidarity among organizations belonging to the same right-wing field (Cinalli, 2004).

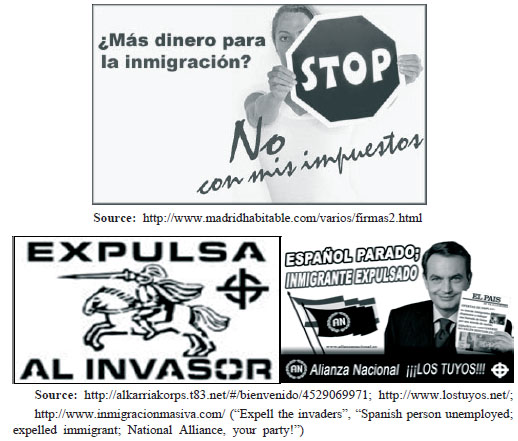

However, it is worth noting that almost a quarter of the organizations analyzed (24.1%) use the Internet to publicize their ongoing political campaign. For example, Nuevo Orden (New Order) promotes a campaign on its website against immigration, inviting visitors to sign an online petition against the use of public funds for the regularization and integration of immigrants. Political campaigns against immigration are also present in numerous other websites (e.g., Alianza Naciónal-Nacionalismo Social, Alkarria Korps, and Inmigración Masiva, see Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Example of political campaigns on the Spanish extreme-right websites

Other examples of political campaigns launched through the web by Spanish extreme-right groups focus on nationalism and revisionism. For example, in 2009 Alianza Naciónal launched a pro-Palestinian (and against Israel) campaign entitled holocaust of who?, and many other Spanish organizations advocate on the web similar pro-Palestinian campaigns (e.g., websites of the groups GipuzkoA88 and Joventudes de la Falange). Very common on the Internet are political campaigns organized in the defense of the national identity and unity of the country against regional autonomies12 (see, for example, the website of Falange Española de la JONS), as well as those against Europe13, the entry of Turkey into the EU14, and the EU Constitution.15

Regarding the use of the Internet by the Spanish extreme right in order to promote a collective identity and reinforce a sense of belongingness to the extreme-right community, our analysis shows that Spanish extreme-right organizations often use the Internet in order to present themselves and define their identity (72.4% of the groups analyzed have a section on who we are or about us on their website). However, it is rarer that one finds the description of the goal of the group (in 32.8% of cases), as well as the names of the leaders, martyrs, and above all the narratives of the group (in 12.1% of cases), which are considered to reinforce the sense of collective identity (Zhou et al., 2005).

Furthermore, beyond the degree of use of the Internet for this purpose, with regard to the type of identity that the Spanish extreme-right organizations construct through the web, a picture emerges of a very fragmented, incoherent, and somehow old identity offered on the websites of these organizations. Analyzing the sections who we are/our mission/our goals, we find, for example, that the term Spanish Falange, which indicates the direct heir of the earlier Spanish fascist party, is contested by several very different organizations (e.g., the Círculos Doctrinales José Antonio, the Falange Española Auténtica, and the Frente Naciónal Español). The Falange Española defines itself on the web as an organization which is the direct heir of Falange Española de la JONS of the 1930s and which defends, as the founding fathers, the social-national values (http://www.lafalange.org/). The Falange Española de la JONS focuses on a political program based, with neo-liberal and economic-istic overtones, on the centrality of the men in the current political and economic system (http://www.falange.es). The organization Falange Española Independiente focuses on historic events, and the Falange Auténtica has as a main point of its program on the web the unity of the country (http://www.falange-autentica.org/).

In terms of issues, themes, and topics presented on the websites, in a considerable portion of the organizations analyzed, the content seems to be distanced very far from the discourse of the (new) European extreme right, ans seems instead to express a nostalgic and closed political culture (Casals, 2004, p. 51). The Spanish organizations show an iconography that shares few features with other European extreme-right groups. Half of the websites analyzed (50% of cases) contain hate symbols. Most of them are typical of the old extreme right ideology recalling the fascist and Nazi period (such as swastikas, Celtic crosses, eagles, and symbols and photos of the Nazi period and Francos regime). Photos of the Francoist period are often found, especially on the websites of nostalgic and revisionist groups. Anti-Semitism does not appear as a characteristic feature of the Spanish extreme-right websites, whereas the anti-Semitic discourse is central for neo-Nazi groups, it is more peripheral for the neo-Falangistas groups and it emerges only when these organizations refer to WWII, or to the Arab-Israel conflict ( ). This derives from the fact that the neo-Falangist extreme right groups do not support anti-Jew racism and differentiate between Zionism and the interests of Jews (Rodríguez, 1999, p. 8).

Only a fifth of the organizations analyzed (22.4% of cases) contain animated and flash banners on their websites, depicting representative figures and symbols that incite visitors to violence toward specific social categories (mostly ethnic minorities and political adversaries). This can be attributed to the fact that the European Nazi-skin sub-culture, coming from Britain from the late 1970s, had little influence on the identity framework of the Spanish (especially political parties) extreme-right groups (Rodríguez, 1999). The main focus of Spanish extreme-right organizations is instead on domestic politics (as well as on the domestic past, e.g., the civil war and the dictatorship). For example, on the homepage of the Spanish extreme-right organization Orden Naciónal, the visitor reads: We have to defend our identity and the original roots of our nation, without forgetting that we possess a culture, a literature, a history and a language, among the most important in the world (from the home page of Orden Naciónal16). However, note that there is a difference between the majority of more nostalgic groups on the one hand, which refer specifically to the Francoist regime (for example, Fundación División Azul17); and, on the other hand, those groups using the Internet as a new tool to propose new contents and discourses (e.g., on immigration, unemployment, the illegal funds to political parties, etc. see for example the website of the group Plataforma per Catalunya18).

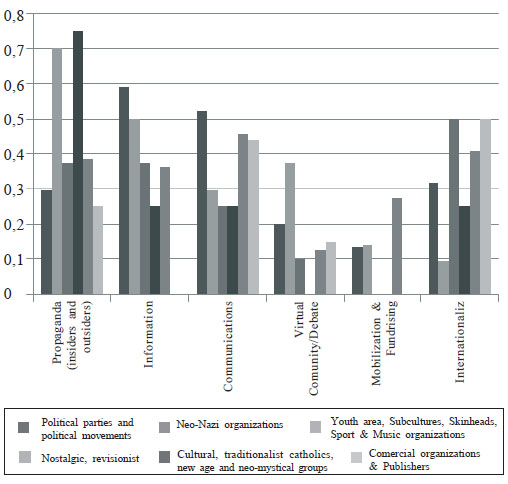

Figure 3 offers a summary of the various forms of online political activism explored in this article, expressing the degree of activity in each dimension (namely: information, communication, the creation of identity, mobilization, and internationalization) by the type of extreme-right organization (each of these additional indexes represents a normalized activity scale varying between 0 and 1).19

Figure 3 - Indexes of forms of Internet usage, by different types of E.R. organizations

The data seem to suggest that the offline organizational characteristics (i.e., belonging to the same sector of the extreme-right milieu) might have an impact on the forms and extent to which the Internet is used for political purposes by extreme-right organizations. Indeed, extreme-right political parties are those more likely to use the web to realize goals such as informing and communicating with the potential audience according to a more traditional use of the Internet as an additional channel to the usual means of politics. On the other hand, sub-cultural youth organizations are more likely to exploit the web in order to mobilize their adherents and to build international contacts and content suggesting a more innovative use of the Internet, as a substitute of sorts for face-to-face interactions and social processes (della Porta and Mosca, 2006a). Furthermore, right-wing nostalgic and revisionist groups are characterized by very high levels of political activism in the new arena of the Internet, especially concerning the use of the Internet for information and the construction of identity.

Conclusion

This study on the Spanish extreme right and its use of the Internet has revealed that the Spanish case does not adhere to the general trend advanced by many scholars and official sources that indicate an increasing use of the web by right-wing groups all over the world (Tateo, 2005). In fact, our data show an online political activism of the Spanish extreme-right groups that is moderate, despite the groups wishes to be present on the web (as testified by the considerable number of right-wing organizations identified that have an online presence).

As seen from our formalized content analysis of the websites, the Internet is a significant tool of these organizations, used for posting information and propaganda. However, unlike the case among other European countries such as Italy, it is not used to the same extent for communication with the potential audience or for stimulating virtual debates among like-minded people, both of which are considered as crucial activities for reinforcing the collective identity of the group (De Koster and Houtman, 2008). Furthermore, in terms of the content (as posted online) of collective identity (even if virtual), our analysis finds a marked cultural backwardness among Spanish extreme-right organizations, which do not use their websites to promote symbols, images, issues, and icons able to connect themselves to topoicommon to other (more successful) European extreme rights (on this point see also Casals, 2004; Caiani and Parenti, 2009). They are mainly focused on their past and, as simply holding up a mirror to other groups, on their web sites trot out the same off-the-shelf symbols, rhetoric, and texts considered as classic for Fascism/Nazism/Franchism, as an identity kit ( ) [of] icons, norms and values (Roversi, 2006, p. 108). Whereas Italian extreme-right organizations make some genuine attempts to promote virtual debates on their websites (Caiani and Parenti, 2009), the potential of the Internet for the mobilization of the activists in offline and online political actions (e.g., organize a demonstration, Petit, 2004) is only moderately exploited by the Spanish groups, which mainly use the web as little more than a showcase to publicize ongoing political campaigns.

According to our social network data, the Internet is not used by the Spanish extreme-right groups in an effort to create either an internal cohesive community or a transnational community (Schafer, 2002; Genstenferld et al., 2003). The network of the Spanish extreme right has emerged (at least on line) to be a very loose chain of contacts, where communication seems to be impeded by barriers of ideological and issue-specific interests (Diani, 2003). Furthermore, it has appeared as an internationally rather isolated community. However, our study also shows that different types of extreme-right organizations use the Internet in order to serve different political goals, suggesting that the offline identity of actors might have an impact on their online political behavior (Calenda and Mosca, 2007).

Although we are aware that the analysis of the use of the Internet by extreme-right organizations does not mirror their real political communication and mobilization outside the web, we are nevertheless convinced that such analysis can help us to better understand such groups (Burris et al., 2000). The results emerging from our study can be related to the political opportunity structure available to the Spanish extreme right in the offline reality. It is worth noting that Spain is one of the European countries showing the lowest level of Internet penetration, measured by access to the Internet (33.6%, whereas the European average is 46.9%; on this see della Porta and Mosca, 2006b). Moreover, the traditional organizational and ideological weakness of the Spanish extreme right (Rodriguez, forthcoming) seems to be in evidence on the web as well. Other studies focusing on the Spanish left-wing organizations have demonstrated that except for a few groups (more specialized in high technologies), social movement organizations are more interested in offline mobilizations and activities rather than in offering Internet services (Jiménez and Calle, 2006, p. 120). Aside from the general Spanish backwardness in the use of the Internet, and in a comparative perspective, it is worth noting that in contrast to what we see among the extreme-right organizations, in recent years their main antagonists (i.e., the Spanish left-wing social movements) have made more frequent use of the Internet for addressing political activities and purposes.20

The segmented structure of the Spanish extreme-right online community offers a reasonable representation of todays Spanish extreme-right outside cyberspace. The organizational milieu of the Spanish extreme right is, in fact, described by many commentators as extremely fragmented and divided into rival splinter factions that have been unable to shake their association with their ultra-authoritarian and antidemocratic history, as well as the fascism of the Franco regime (Norris, 2005, p. 66). Also, the divisions and ideological conflicts that characterize the Spanish extreme right in the real word are reproduced and emphasized in their representation on the web, often influencing their use of the Internet. The right-wing organizations analyzed use the web not only to spread their message and keep contact with other similar groups in the country, but also to build a collective identity. However the type of identity constructed on the web shows the same internal contradictions they suffer in the offline reality. The term Spanish Falange, which indicates the direct heir of the earlier Spanish fascist party, is, for instance, claimed by several groups that nevertheless demonstrate diverse ideologies and political action strategies. Some of thees refer specifically to the Francoist regime (for example, Fundación División Azul) and are less violent in their web-content language and imagery; others look directly to Nazism as the north star of their identity and ideology.

Moreover, the Spanish extreme right has been late in including in its ideological framework certain topics that are well spread in the New European extreme right, such as foreigners and immigration issues also using less violent tones in comparison to the radical right-wing forces in other European countries (e.g., France) (Casals, 1999). Indeed, as many authors emphasize, the Spanish extreme right has been not able to renovate itself by welcoming into its framework the ideological values of the so called new right (such as anti-Semitism and opposition to immigration), which were spreading in Europe (Rodríguez, 2006). According to Rodríguez (1991, 1999), Spanish extreme-right elites have not understood the needs of a modernizing society and have been unable to adapt the traditional values of Francos regime to a new democratic country and to the new challenges of modernity. In general, the Spanish extreme-right organizations on the web do not use the same symbols, or the same rhetoric linked to Fascism or Nazism that would enable them to build a coherent and unifying ideology. If some authors (Davies and Jackson, 2008, pp. 197-198) have pointed out that nostalgia for the Franco regime is a kind of glue that still unites activists, for other types of groups (youth and sub-culture organizations most of all) the Francoist heritage is irrelevant.

In sum, our study has shown that the Spanish extreme right does not make extensive use of the Internet, confirming what has been observed for other types of civil society organizations (in particular for left-wing groups). In general it has been demonstrated that except for a few civil society groups (more specialized in high technologies), social movement organizations are more interested in offline mobilizations and activities rather than in offering Internet services (Jimenez and Calle, 2006, p. 120). Characterized by historical organizational weakness and ideological fragmentation, the Spanish extreme right seems to reproduce these features online. It is unable to fully exploit the new potential offered by the Internet – failing to use it as a new forum of communication, as a means to renovate itself, for adopting new topics and action strategies, or to build an identity that stays abreast of the times.

References

Ackland, R. and Gibson, R. (2004), Mapping political party networks on the WWW. Paper presented at the Australian Electronic Governance Conference, 14-15 April 2004, University of Melbourne. Available at: http://acsr.anu.edu.au/staff/ackland/papers/politicalnetworks.pdf [ Links ]

Atton, C. (2006), Far-right media on the Internet: culture, discourse and power. New Media and Society, 8 (4), pp. 573-587. [ Links ]

Bennett, W. L. (2003), Communicating global activism: strengths and vulnerabilities of networked politics. Information, Communication and Society, 6 (2), pp. 143-168. [ Links ]

Burris, V., Smith, E., & Strahm, A. (2000) White supremacist networks on the Internet. Sociological Focus, 33 (2), pp. 215-235. [ Links ]

Caiani, M., Parenti, L. (2009) The dark side of the web: Italian right-wing extremist groups and the Internet. South European Society and Politics, 14 (3), pp. 273-294. [ Links ]

Caldiron, G. (2001), La Destra Plurale, Roma, Manifestolibri. [ Links ]

Calenda, D., Mosca, L. (2007), Youth online: researching the political use of the Internet in the Italian context. In B. Loader, (eds.), Young Citizens in the Digital Age: Political Engagement, Young People and New Media, New York/London, Routledge, pp. 52-68. [ Links ]

Carter, E. (2005), The Extreme Right in Western Europe: Success or Failure, Manchester and New York, Manchester University Press and Palgrave. [ Links ]

Casals, X. (1999), La ultraderecha española: una presencia ausente (1975-1999). Paper presented to the Ortega y Gasset Foundation Seminar. [ Links ]

Casals, X.(2001),Europa: una nova extrema dreta. Col. Papers de la Fundació, Fundació Rafael. [ Links ]

Casals, X. (2004), Lultradestra Spagnola (1975-2004): La lenta omologazione con lEuropa. Trasgressioni, 39, pp. 51-60. [ Links ]

Chase-Dunn, C., Boswell, T. (2002), Transnational social movements and democratic socialist parties in the semiperiphery. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the California Sociological Association, http://irows.ucr.edu/papers/csa02/csa02.htm. [ Links ]

Chau, M., Xu, J. (2006), A framework for locating and analyzing hate groups in blogs. In Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, July 2006. [ Links ]

Chhibber, P. and Torcal, M. (1997), Elite strategy, social cleavages, and party systems in a new democracy: Spain.Comparative Political Studies, 30 (1), pp. 27-54. [ Links ]

Cinalli, M. (2004), Horizontal networks vs. vertical networks within multi-organizational alliances: A comparative study of the unemployment and asylum issue-fields in Britain. European Political Communication Working Paper Series, 8 (4), Online available at http://www.eurpolcom.eu/exhibits/paper_12.pdf, [visited in 19-07-2011]. [ Links ]

Cunha, C., Martin, I., Newell, J., and Ramiro, L. (2003), Southern european parties and party systems, and the new ICTs. In R. Gibson, P. Nixon, and S. Ward (eds.), Political Parties and the Internet. Net gain?, New York & London, Routledge, pp. 70-98. [ Links ]

Davies, P., Jackson, P. (2008), The Far Right in Europe, Oxford/Westport, Cunnecticut, Greenword World Publishing. [ Links ]

De Koster, W., Houtman, D. (2008), Stormfront is like a second home to me: On virtual community formation by right-wing extremists. Information, Communication & Society, 11 (8), pp. 1155-1176. [ Links ]

della Porta, D., Mosca, L. (2006a), Democrazia in rete: stili di comunicazione e movimenti sociali in Europa. Rassegna Italiana di Sociologia, 4 (Oct-Dec), pp. 529-556. [ Links ]

Della Porta, D., Mosca, L. (2006b), Democracy in the Internet: a presentation. Report on Work Package 2 of the Project Demos (Democracy in Europe and the Mobilization of Society; http://demos.eui.eu). [ Links ]

Diani, M. (2003), Comunità reali, comunità virtuali e azione collettiva. Rassegna Italiana di Sociologia, 1, pp. 29-51. [ Links ]

Fasanella, G., and Grippo, A. (2009), LOrda Nera, Milano, Rizzoli. [ Links ]

Garrett, R. K. (2006), Protest in an information society: A review of literature on social movements and new ICTs. Information, Communication and Society, 9 (2), pp. 202-224. [ Links ]

Gerstenfeld, P. B., Grant, D. R., and Chiang, C. (2003), Hate online: a content analysis of extremist Internet sites. Analysis of Social Issues and Public Policy, 3 (1), pp. 29-44. [ Links ]

Hernández A., (2010), Plataforma per Catalunya: emergence, features and quest for legitimacy of a new populist radical right party in the region of Catalonia. Paper based on the project Immigration policy and disaffection in the local context: analysis of the social and spatial development of Plataforma per Catalunya executed by J. Subirats, M. Aramburu and A. Hernández and funded by the Spanish Centre for Sociological Research. [ Links ]

Informe Raxen. Xenofobia Ultra en España, (2007), Madrid, Movimiento contra la Intolerancia. [ Links ]

Informe Raxen. Racismo, Xenofobia, Antisemitismo, Islamofobia, Neofascismo, Homofobia y otras manifestaciones de Intolerancia a través de los Hechos. Especial 2008, (2008), Madrid, Movimiento contra la Intolerancia. [ Links ]

Jiménez, M. and Calle, A. (2006), Spanish report: Internet and the Spanish global justice movement. Report on Work Package 2 of the Project Demos (Democracy in Europe and the Mobilization of Society; http://demos.eui.eu). [ Links ]

Levin, B. (2002), Cyberhate: A legal and historical analysis of extremists use of computer networks in America. American Behavioral Scientist, 45, pp. 958-988. [ Links ]

Margolis, M., Resnick, D., and Wolfe, J. (1999), Party competition on the Internet: minor versus major parties in the UK and USA. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 4 (4), pp. 24-47. [ Links ]

Minkenberg, M. (1998), Die neue radikale Rechte im Vergleich, Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen. [ Links ]

Norris, P. (2005), Radical Right: Voters and Parties in the Electoral Market, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Petit, C. (2004), Social movement networks in Internet discourse. Paper presented at the annual meetings of the American Sociological Association, San Francisco, August 17. [ Links ]

Post, J. M. (2005), Psychology. In Addressing the Causes of Terrorism, Report of the working group at the International Summit on Democracy, Terrorism and Security, 8-11 March, Madrid, The Club de Madrid Series on Democracy and Terrorism, 1, pp. 7-12. [ Links ]

Qin, J., Zhou, Y., Reid, E., Lai, G., and Chen, H. (2007), Analyzing terror campaigns on the Internet: Technical sophistication, content rightness and web interactivity. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 65, pp. 71-84. [ Links ]

Rodríguez , J. L. (1991), Origen, desarrollo e disolución de Fuenza Nueva. Revista de Estudio Políticos Nueva Epoca, 73, pp. 261-187. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, J. L. (1999), Antisemitism and the extreme right in Spain (1962-1997). Acta, 15, Online Available at http://sicsa.huji.ac.il/15spain.html, [visited in 19-07-2011]. [ Links ]

Rodríguez , J. L. (2006), De la vieja a la nueva extrema derecha (pasando por la fascinación por el fascismo. Historia Actual Online, 9 (Invierno 2006), pp. 87-99. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, J. L. (forthcoming), The Spanish extreme right: from neo-Francoism to xenophobic discourse, in mapping the extreme right in contemporary Europe: from local to transnational. In A. Mammone, E. Godin, and B. Jenkins (eds.), Mapping the Extreme Right in Contemporary Europe: from Local to Transnational.Oxford, U.K. [ Links ]

Roversi, A. (2006), LOdio in Rete. Siti Ultras, Nazismo Online, Jihad Elettronica, Bologna, Il Mulino. [ Links ]

Schafer, J.A. (2002), Spinning the web of hate: web-based hate propagation by extremist organizations. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 9 (2), pp. 69-88. [ Links ]

Scott, J. (2000), Social Network Analysis: an Handbook, Sage, London. [ Links ]

Tateo, L. (2005), The Italian extreme right on-line network: An exploratory study using an integrated social network analysis and content analysis approach. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10 (2), Online available at http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10/issue2/tateo.html, [visited in 19-07-2011]. [ Links ]

TE-SAT (2007), Report on EU Terrorism Situation and Trend, Europol. [ Links ]

Trechsel, A., Kies, R., Mendez, F., and Schmitter, P. (2003), Evaluation of the Use of New Technologies in Order to Facilitate Democracy in Europe, E-democratizing the parliament and parties of Europe. Report prepared for the Scientific Technology Assessment Office, European Parliament, (http://edc.unige.ch/publications/edcreports/STOA/main_report.pdf). [ Links ]

Weimann, G. (2004), www.terror.net: How Modern Terrorism Use the Internet. Special Report, US Institute of Peace. [ Links ]

Whine, M. (2000), The use of the Internet by far right extremists. In T. Douglas (eds.), Cybercrime: Law, Security and Privacy in the Information Age, London, Routledge, pp. 234-250. [ Links ]

Zhou, Y., Reid, E., Qin, J., Chen, H., and Lai, G. (2005), U.S. domestic extremist groups on the web: link and content analysis. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 20 (5), pp. 44-51. [ Links ]

Received 11-10-2010. Accepted for publication 16-8-2011.

Notas:

1 This article is part of a broader project on right-wing Extremism Online in Europe and the United States financed by START, University of Maryland.

2 ADL (2001), Poisoning the Web: Hatred Online. Internet Bigotry, Extremism and Violence. Online available at http://www.adl.org/poisoning_web/introduction.asp, [visited in 19-07-2011].

3Between 2000 and 2004, for example, the Spanish extreme right won 0.1% of votes in the national elections (vs. 13.2% of votes in France and 16.3% in Italy in the same period), performing even worse in the most recent years (in the 2008 national elections, none of the extreme right parties were able to obtain even 0.1% of ballots cast).

4 On the reputational approach, see Scott (2000). The process was repeated up to the point when it became impossible to add new extreme-right web sites or organizations to our sample that had not already been encountered. The classification (inclusion in the population) of the Spanish extreme-right organizational websites was based on the self-definition of the group and content of the websites (see Tateo, 2005).

5 For the classification of the Spanish organizational websites into broader categories, we referred to the most common typologies that have been proposed for the study of the extreme right (Burris et al., 2000; Tateo, 2005), adapting them to the specificities of the Spanish contexts. However, we aware that these categories are not necessarily mutually exclusive and that in reality they can be found in combination. The analysis was conducted between March and June of 2009.

6For its construction we relied on terrorism research (e.g., Weimann, 2004) as well as on studies that have used a formalized approach for the study of extremist websites (e.g., Gerstenfeld et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2005; Qin et al., 2007). We also draw on a recent similar study on (radical) left-wing organizations websites (see the Demos project, http://www.demos.eui.eu/).

7 The instruments of social network analysis have not been frequently applied to the study of the Internet and even less so for its use by extremist groups. Hereinafter, we will treat the links as indicators of closeness, traces of communication, instruments for reciprocal help in attaining public recognition, and for potential means of coordination (Burris et al. 2000, p. 215). At the same time, social network analysis has been considered as particularly interesting for social movements, which are, indeed, networks in themselves, the formal characteristics of which have been referred to in the development of theories of collective behavior (see for example Diani, 2003). This section is based on a comparison between the levels of some of the most common measures of network analysis, namely the in-degree (which measures the centrality of an actor in a network, counting how many contacts a certain actor receives from other actors), the average distance (the distance, on average, of the shortest way to connect any two actors of the network), and the density of the network (which expresses the ratio between the existing contacts among the organizations in the network and the number of possible contacts). For these measures, see Scott (2000). All lower levels used in the codebook are binary (0-1).

8For example, Spanish extreme-right political parties are linked mainly with extreme-right political parties in other European countries, sub-cultural skinhead groups with skinhead groups, etc. On the website of the political party España 2000 we find more than 20 links to right-wing political parties of other European countries, such as the Dutch Vlaams, the French Front National, and the Italian Movimento Sociale Fiamma Tricolore and Forza Nuova, etc.

9 For example, on the website of Nuevo Orden (http://www.nuevorden.net/) we find leaflets on immigration, holocaust, Adolf Hitler, and the social nationalism of the 1930s. See also the website of the group Fundación División Azul (http://www.fundaciondivisionazul.org/).

10 E.g., Fundación División Azul (http://www.fundaciondivisionazul.org/).

11 E.g., http://www.viejaguardia.es/; http://libreopinion.com/members/bastion_norte/portada.htm.

12 E.g., http://www.lostuyos.net/

13 E.g., http://www.falange.es

14 E.g., http://www.turquianogracias.tk/

15E.g., http://www.falange-independiente.com/

16 http://www.libreopinion.com/members/orden_nacional/ordennacional.html

17http://www.fundaciondivisionazul.org/

18 http://www.pxcatalunya.com/webnormal/

19These five additive indexes derive from the sum of the lower level indicators used for each dimension (e.g., as for informing, indicators such as news reporting, publishing documents, offering bibliographical references etc.; see the method, Section 2), which has been normalized in order to vary between 0 and 1. In order to allow for comparison between indexes (composed of different numbers of indicators) each of them has been standardized to the 0 to 1 range by dividing the resulting score by the maximum possible value.

20For example, on May 15th 2011 (in the wake of similar protests in Greece and Portugal) a large national protest was organized in Spain (the so-called 15-M Movementor theSpanish revolution) by Democracia real YA (the Real democracy NOW), a civilian digital platform with 200 other small associations. It involved a series of demonstrations in many Spanish cities organized and coordinated through the social networks (such as Twitter and Facebook).