Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.201 Lisboa out. 2011

A new era for French far right politics? Comparing the FN under two Le Pens

Michelle Hale Williams*

* University of West Florida, 11000 University Pkwy Pensacola, Florida 32514, EUA. e-mail: mwilliams@uwf.edu

Abstract

With 2012 elections looming on the horizon in France, much political attention has focused on the new leader of the National Front, Marine Le Pen. She is polling quite well outpacing many of her mainstream party candidate rivals for the 2012 French presidency and the public appears to have embraced her with open arms. Hailed as a promising new face of French politics, a wide swath of the French electorate indicates confidence in her ability to bring needed changes to France. Yet does she really represent a dramatic departure from former FN policies and positions? This article examines the model of the FN during the leadership of Jean-Marie Le Pen in comparison with that seen in the first eight months of Marine Le Pens leadership in order to address this question.

Keywords: Marine Le Pen; National Front; France (FN); radical right-wing parties.

Uma nova era para a extrema-direita francesa? Uma comparação entre a Frente Nacional dos dois Le Pen

Resumo

Com a iminência das eleições francesas de 2012, muita da atenção política se tem centrado na nova líder da Frente Nacional, Marine Le Pen, que tem tido um desempenho notável nas sondagens, ultrapassando muitos dos seus rivais dos partidos tradicionais na corrida para a presidência francesa, e sendo aparentemente acolhida de braços abertos por grande parte do eleitorado. Considerada uma nova e promissora figura no panorama político francês, uma larga fatia do eleitorado demonstra confiança na sua capacidade para trazer ao país a mudança necessária. Mas será que ela representa, de facto, uma ruptura com as antigas posições políticas da FN? O presente artigo examina o modelo da FN sob a liderança de Jean-Marie Le Pen comparando-o com o dos primeiros oito meses da liderança de Marine Le Pen por forma a analisar esta questão.

Palavras-chave: Marine Le Pen; Frente Nacional; França (FN); partidos de direita radical.

Introduction

Jean-Marie Le Pen called the early years in the life of the National Front as a far right political party a period of crossing the desert (DeClair, 1999, p. 42). With this reference he expressed the difficulty encountered in constructing a viable far right party in France and the experience of his party from its founding in 1972 until its initial signs of stability and growth in the early 1980s. Radical right-wing parties had languished in France for nearly four decades following World War II. After the collapse of Marshall Petains Vichy regime and the reinstatement of democracy under the Fourth Republic, only loose groupings of nationalists, authoritarians, and ethnocentrists remained. They existed largely at the periphery of the political system and exerted negligible influence.

It was not until the early 1980s that fortunes began to be reversed for French parties of the radical right wing, as they started to have localized success in gaining public office. Since then, the French National Front party (FN) has steadily gained ground. This growth was seen clearly in 2002, when Jean-Marie Le Pen received the second highest percentage of the popular vote on the first ballot and advanced to the second round of elections. The party languished somewhat thereafter, earning disappointing electoral results in 2007. However, in 2011, with the first party leadership transition passing the torch from father to daughter, national attention has turned to the FN once again. Marine Le Pen appears to be repositioning and refocusing the FN. Early indications ahead of 2012 parliamentary and presidential elections in France suggest a favorable electoral response.

There is a temptation to interpret the leadership transition of the FN as the inauguration of not only a new era but of a new breed or brand of the party. This article investigates the extent to which such temptations should be indulged through a structured case-study comparison of the FN under two leaders, Jean-Marie Le Pen and Marine Le Pen. While acknowledging that data for the latter case are limited to the initial months following the leadership transition, the author contends that initial indicators have already emerged. Using a structuralist approach and logic for understanding party behavior based on opportunities and constraints, the analysis employs descriptive indicators for classifying party system dynamics as well as party organization characteristics. Descriptive indicators were selected based on empirical evidence and the scholarly literature on the FN under Jean-Marie Le Pen, then juxtaposed with either confirmation or disproof based on the preliminary evidence in the case of Marine Le Pen.

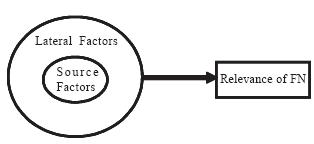

Operating under the assumption that party competitiveness involves both endogenous or source factors pertaining mainly to intra-party dynamics as well as exogenous or lateral factors pertaining to the party system and opportunity structures therein, both types are considered here.1

Explaining Far Right Party Competitiveness in France

Examination of exogenous or lateral factors requires focus on the party system. This includes the position of other parties on a Downsian spectrum and the ideological space occupied by other parties compared to that left vacant for opportunism by the far right parties (Downs, 1957). By contrast, endogenous or source factors involve people, structure, and dynamics within the political party itself. In the evaluation that follows, key features of the Jean-Marie Le Pen party model will be compared with those of the Marine Le Pen party model, based on the preliminary evidence gathered from her first eight months in the office of party leader.

THE NATIONAL FRONT UNDER JEAN-MARIE LE PEN: LATERAL EXPLANATORY FACTORS

Party System Alignments, Openings and Opportunity Structures

The French party system has experienced various periods of change in the Fifth Republic, as parties have developed, adjusted positions, split, and merged. However, the party system has arguably been one of greater stability rather than volatility in the sense that parties and their ideological lines of division have remained largely intact. Party genealogy models illustrate the endurance of French parties of the FifthRepublic, most of which have their roots dating to earlier times (see for instance, Safran, 2003; Knapp 2004, p. 5; Platone, 1997, p. 56). In fact, relatively few new parties have emerged in the French system after 1958, most notably the Greens and the FN.

A period of perceived instability followed the Socialist governance that ended in 1986. This stemmed from several sources and created opportunities for small parties (Cole, 2003, p. 14). Small parties like the FN benefitted from the lack of ideological coherence among socialists, communists, and Gaullists at this time. The rupture in traditional ideological threads proved especially profound in its impact on the French party system, for at least two reasons. First, France is asserted to possess a relatively high level of ideological orientation and partisan discourse in its republican political tradition (Cole, 2003, p. 24; Knapp, 2004, p. 13). To confuse traditional lines of cleavage means more in the case of France than what may be the case in other countries. Second, this shift marked the beginning of a right to left alternation of the governing party coalitions that was unprecedented in the Fifth Republic. Prior to this point, the Gaullists had governed without interruption from 1958 to 1981, followed by Socialist rule to 1986. From this point on, control swung back and forth between the mainstream parties in 1981, 1986, 1988, 1993, 1997, and 2002 (Knapp, 2004, p. 44). The initial rise of the FN coincided with a sea change in French governance that likely contributes to the lasting presence and impact-potential of the FN.

Communism in Decline Impacts the Working Class Vote

The discrediting of left-wing ideologies, and in particular communism, has created opportunities for the FN to expand its base of support, attracting constituents formerly positioned on the left. Beginning in the early 1980s, communists in France have modified their ideological position to move into alliances with the center-left socialists (Hayward, 1990). As they have moderated and moved toward the center, radicals that favor the more revolutionary politics of Marxism-Leninism have become disgruntled. For example, a core base of support for the communist left has traditionally come from the working class. Yet the FN planned its 2002 election campaign in attempts to appeal to the working class voter (Ceccaldi, 2002; Gollnisch, 2002). Working class frustrations had become a target of far right issue positioning and populist appeals, as the record of communist parties to deliver on their promises revealed continued failure, and worse still in the minds of true ideologues, continuous compromise.

Issue Co-optation Favoring the Co-optee

To the extent that issue co-optation in the zero-sum game world of electoral politics can mean having ones thunder stolen and ones voters along with it, the fact that the FN experienced considerable issue co-optation on two of their most central issues, immigration and law & order, might prove a hindrance to party advancement. After all, if other parties were essentially stealing their hot issue and their policy positioning around the issue, one might expect the other parties to steal the supporters away as well. However, the opposite actually came about. From the party founding in the mid-1980s, they have been leading the pack among French political parties when it comes to taking particular issue positions on immigration and law & order. Scholarly evidence apparently supports his claim with the finding that on the immigration and law & order issues the FN did set the political agenda, leading other parties to embrace the FN position to one degree or another and focus on immigration, along with the imperative of restriction (Schain, 1999, p. 8; Schain, 2002; Hainsworth and Mitchell, 2000, p. 453). Jean-Marie Le Pen consistently claimed to say out loud what French people were thinking and feeling in the classic style of populism, and other parties in the French system seized upon his claim.

One reason that issue co-optation strengthened rather than weakened the FN testifies to the issue-positioning skill of the FN in the 1980s. They were able to recognize an issue that was becoming increasingly significant before other parties did so. They appeared to have a better finger on the pulse of the French public than other parties at the time and were paying closer attention to voter demands. While Pippa Norris placed greater emphasis on party supply side factors in her comprehensive book that seeks to account for the success of radical right parties around the world (Norris, 2005), she devoted a chapter to demand, suggesting that successful radical right parties listen to the concerns of the electorate, even if they end up manipulating them when the time comes to offer them up to the voters for electoral consumption. To effectively utilize an omnibus issue like immigration (Williams, 2006, pp. 60, 97) requires political acumen in the sense of knowing precisely how to position the public appeal. When other parties began to respond and take positions on the immigration issue, the issue ownership already belonged to the FN. Thus, rather than taking votes away from the FN through co-optation, larger party encroachment served to increase the FNs stature, moving the French political center farther to the right (Williams, 2006, pp. 107-108). Co-optation in fact served to bolster the FNs legitimacy claims.

It must be noted that following the 2002 elections a reversal occurred whereby issue co-optation began to favor the co-optor rather than the co-optee. By 2007, the publicly perceived ownership of those issues had transferred to Nicolas Sarkozys Union for a Popular Movement party (UMP). Sarkozy and the so-called blue wave of support blue being the color of the party appeared to displace the FN, using its own message and priorities. The UMP became the party of law & order and restrictive immigration and Sarkozys popularity and perception as a results-getter led to suggestions of a decline or even demise of the FN. Sarkozy made key appointments to his new government in order to showcase his focus on immigration and law & order, such as his creation of a new government Ministry of National Identity and Immigration (Bell and Criddle, 2008, p. 191). Sarkozy appeared to do what his predecessor Jacques Chirac had not, namely win back the mainstream right and all those within the French electorate concerned about law & order and immigration.

THE NATIONAL FRONT UNDER JEAN-MARIE LE PEN: SOURCE EXPLANATORY FACTORS

Leadership Style and Strategy

The personality and leadership style of Jean-Marie Le Pen have, without doubt, provided a crucial ingredient in the progress of the National Front through various stages of its development. His style has strong elements of charisma and populist approachability, yet is infused with ideology masquerading as everyday discourse and concerns. There is a latent political acumen behind Le Pens commanding presence and rhetoric that is decidedly strategic and savvy, as well. He crafted much of the mid-1980s transformation of the party. Yet, he also appeared to know when to call in counsel from party intellectuals and other right-wing ideologues.

The public image and style of Jean-Marie Le Pen has been widely compared with that of other West European radical right-wing party leaders of the late twentieth century, including Jörg Haider, the former leader of the Austrian Freedom party (FPÖ), and then of its splinter party, the Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ), prior to his death in 2008, Filip Dewinter of the Belgian Vlaams Belang, and Pim Fortuyn of his namesake party LPF in the Netherlands. Le Pen is frequently noted as an eloquent and effective public speaker (Givens, 2005, p. 41; Hainsworth, 2004; Pedhazur and Brichta, 2002). In France in early 2002, at what some have called a pinnacle year for Jean-Marie Le Pens success as leader of the FN, a staff assistant to French MP Jean-Marie Bockel of the Socialist Party (PS) described the allure of FN leader Jean-Marie Le Pen in an interview saying, the media will not be able to resist the temptation to put him [Le Pen] forward. That is what has happened because he is so appealing, so attractive, and the media ratings go high when he appears and when he speaks (Prager, 2002). She described how the French cannot help themselves and are drawn to Le Pen magnetically even when they disagree with him.

Jean-Marie Le Pen has been plagued from time to time by gaffes, including the use of inflammatory language and racist imagery. This has hurt the credibility of the party at various points in time. Yet, a populist-likeability coupled with his charisma helped to redeem Le Pen among many supporters. Both charisma and populism thrive on crisis. Crisis points often produce opportunities for charismatic leaders who move in to supply messages of understanding, comfort, problem-solving, and restabilization (Eatwell, 2005, p. 109). Populists capitalize on crises, pointing to the failure of other parties as producing or contributing to current problems (Betz, 1994). Jean-Marie Le Pen chose the right time to adopt a populist rhetoric and style (Vernet, 2002), making him both interesting and approachable.

It would be a mistake to reduce Le Pens leadership to style alone. The substance of Le Pens rhetoric and message shows deep roots in intellectual traditions combined with contemporary nuances often emerging from right-wing think tanks. Le Pens articulation of ideology might easily be called veiled, to the extent that it was presented in relatable and accessible ways that mask elements of intellectual sophistication within right-wing thought. As Le Pen undertook repositioning of the party in the early to mid-1980s, he employed ideology dating to Poujadism, combining elements of fresher waves of right wing thought coming from the nouvelle droite with the assistance of party ideologues (Rydgren, 2004, pp. 17-18). Particularly during the period leading up to the 1988 presidential elections, Le Pen recruited intellectuals away from splinter groups of the mainstream right (Declair, 1999, pp. 64 and 162). Bruno Mégret emerged within the FN as a chief architect of its reinvented positions.

Issue Focus and Positioning to Expand the Base

The evidence has already been presented above on issue co-optation showing how the FN brought immigration and law & order to the forefront of the French political agenda beginning in the mid-1980s. Immigration was not a contentious issue driving French political behavior or causing alarm among French people until the FN made it an issue in the minds of people. This strategic maneuver allowed the party to position itself for maximum visibility and response.

Yet, in addition to crafting its niche issue positions, the party had to recast its image to establish itself as a legitimate competitor with clear distance from fascists, Nazis, and racists of all varieties. This task proved complicated, in part because the FN of the 1970s had made overtly racist and white supremacist remarks in its official party publications (Davies, 1999, p. 21). However, Jean-Marie Le Pen and others in the party executive committee known to articulate markedly conservative-right ideas on questions of national identity, such as Bruno Gollnisch, battled constantly to avoid gaffes through their use of inflammatory or overtly racist rhetoric in public speeches and interviews. Bruno Mégret employed the term national preference from the early 1990s to sanitize the partys strong opposition to immigration and their coupling of law & order as a border control issue related to security (Pégard, 2002). The arguments became more rational in appearance when framed in this way. Pascal Perrineau noted how astute the FN was to realize that in raising security concerns with regard to immigrants, such as those Muslims in France coming predominantly from North Africa; it could tap into unresolved feelings of the French with respect to the Algerian War (Perrineau, 2000, p. 267). Increasingly, the FN arguments were couched in terms of economic and political threats rather than as an issue of cultural identity.

The ultimate goal of all repositioning efforts was to broaden the support base for the party. Rather than targeting a narrowly proscribed demographic niche, the FN increasingly aimed at capturing the median voters, those situated on the right ideologically but not just the far right, and also the working class. Like their larger mainstream party counterparts on the left and right, they wanted to cast their nets widely in order to attract as many supporters as possible. In 2002, when I spoke with a party bureaucrat at the FN main office located at that time in St. Cloud, he stressed that the target demographic for upcoming elections was the wider French electorate. He said We reflect what people think. We are not like the communists or socialists who are just about ideology. We think with reflection. We think always of the national interest. If you think of the national interest, you preserve the interest of the people (Ceccaldi, 2002).

There are strong populist undercurrents in such a statement with the idea of representing the average person, the median voter, and by saying that their party manifests the national interest. Yet, he also specifically claimed that the FN renounces ideology. Here the implication was that the FN goal structure is consistent with that of a catch-all party whereby parties strive to win at the expense of ideological purity (Williams, 2009, p. 594). The aim becomes party growth, and for a traditionally far-right-of-center party this means expanding toward the center. The FN reached not only toward the center to attract moderates of the right-wing but also across the left / right dividing line to disenchanted leftists including the working class voters who formerly voted for either the socialists or the communists. As James Shields noted, the catch-all strategy worked for the FN to the extent that they became contenders and a threat to the traditional mainstream parties. He indicated that especially with their showing in regional elections by the late 1990s, the FN had started to, threaten the two big mainstream right parties (Shields, 2011). While the majoritarian French electoral system has always done much to restrict FN access to seats in the national parliament, apart from 1986, when the electoral law was temporarily changed to proportional representation, both of the mainstream parties confronted encroachment from the FN. These parties resorted to evasive action at one point, going so far as to change electoral rules at the regional level as a stop gap measure to avoid significant loss of their base to the FN.

PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS OF THE NATIONAL FRONT UNDER MARINE LE PEN: LATERAL EXPLANATORY FACTORS

Party System Alignments, Openings, and Opportunity Structures

The perceived legitimacy and public credibility on law & order and the immigration issues with which Nicolas Sarkozy took office in 2007 appear to have been exhausted by 2011. As Michel Onfray puts it, Sarkozy has exhausted the patience of supporters through his accumulation of errors politically (Onfray, 2011). Despite a fair record of policy change that has produced some tangible benefits for the French people, Sarkozys approval and public confidence have waned among the French electorate. In May 2011, a TNS / SOFRES poll showed Marine Le Pen to be the favorite candidate on the right wing, capturing 29 percent of the popular favor, while Nicolas Sarkozy lagged a full nine percentage points behind her (Pierre-Brossolette, 2011). The rationale for Sarkozys falling poll numbers cannot be readily attributed to a lack of policy action or even policy success to deliver on his promises. He has acted to bring change in the areas of policy that put him in office in 2007, including right-wing economic reform measures such as a law raising the retirement age of workers, change to labor laws to limit the power of unions, and a government pledge to taxpayers that they will not be asked to pay more than half of what they earn in taxes (Caldwell, 2011, pp. 21-22). In policy measures, he has been tough on crime and restrictive on immigration, just as he said he would be.

Meanwhile, the mainstream left struggled to find a suitable candidate to oppose Sarkozy in 2007 when they settled on Ségolène Royal, and they appear to be struggling to do the same ahead of the 2012 elections. As Christopher Caldwell expressed it in March 2011, their party [PS] seems booby-trapped against producing a candidate the electorate at large can tolerate (Caldwell, 2011, p. 23). For the PS, the elections of 2002 have ignited a firestorm on the left with criticism of the handling of the campaign abounding (Bergounioux et al., 2002; Noblecourt, 2002). The Socialists had a weak platform in 2002 and positioned themselves in the ideological center, which many voters on the left found unappealing (Riding, 2002, p. A6). They continued to lack a clear message and position in opposition to the mainstream right UMP in 2007. By all accounts, the Socialist Party in France has faced a critical juncture over the past decade. They sit at an ideological fork in the road, needing to carve out clear issue space on the left and choose between a traditional pro-worker orientation and a shift toward more liberal economic policy ideas. With the global economic downturn of recent years and EU austerity measures to address the crisis in Europe, an economic-liberal positioning of the PS could position the Socialists to recapture centrist voters with pragmatic, material motivations. Such voters prioritize their pro-business economic interests and have aligned themselves with the center-right camp in recent years not because of the Union for a Popular Movement nationalist rhetoric or advocacy of a return to basic values, but strictly on the grounds of economic policy. On the other hand, their traditional working-class constituency appears to be looking for its proponent and has increasingly looked toward the FN for this.

Furthermore, both the UMP and PS appear guilty by omission in the eyes of the French public on the issue of European unity. The French public has become increasingly anti-EU in the wake of the global financial crisis, and this sentiment builds upon existing resistance to deeper integration under EU supranationalism voiced by the French public overtly with their majority voice rejection of the Lisbon Treaty in 2005. The UMP and PS increasingly appear to have lost touch with the French electorate as they continue to pursue overt support of the EU against the popular will (Onfray, 2011). Survey data from February 2011 show a French public clearly rejecting the EU in the wake of the global financial crisis. Eighty-nine percent of French indicated that today economic markets rather than states run the world and 74 percent said that the European treaties have put France in a straightjacket in terms of policy options (Mergier and Fourquet, 2011, p. 30). While the mainstream parties remain committed to the EU endeavor, the FN has made their anti-EU position well known, tapping into such public concerns over the consequences of excessive restrictions for recovery from the global financial crisis (Caldwell, 2011, p. 24).

With disarray and uncertainties on both the mainstream left and right ahead of 2012 elections, opportunity structures have been favorable, with openings appearing in the French party system for the FN. In fact, polls have consistently shown Marine Le Pen to be outpacing the best candidates from the expected field of the left and right during her first eight months in office. Among Sarkozy voters polled, just slightly more than half (57 percent) of them said that they would vote for him again, while 15 percent said that they would vote for Marine Le Pen (Mergier and Fourquet, 2011, p. 10). Between October 2010 and April 2011, Marine Le Pen gained intended voters across all demographic categories and from voters who had supported all other political parties contesting 2007 elections that were mentioned in the survey, including the UMP, PS, UDF, and Communists (Mergier and Fourquet, 2011, p. 15).

Attracting the Working Class Vote: Is Communism still in Decline?

The working class vote is being courted by a variety of parties. At the PS Party Congress in Dijon in May of 2003, they began extending an olive branch to their counterparts on the Left, the various French communist party manifestations. Union leaders who are also prominent communists were invited to address the party congress. Those in attendance discussed recruitment efforts for the 2004 regional and European elections, suggesting an appeal to all French left-wing parties to collaborate in candidate selection. However, the move toward the left fell short of advocating a union of the French Left. As Socialist party first secretary François Hollande explained, there is no need to get married in order to live happily together (Economist, 2003, p. 55). The opportunities available to Socialists during the time of François Mitterrand to join forces with other left-wing parties may not exist for the Socialist party today. Instead, Communists, Trotskyists, and Greens have been pursuing their own self-interested advance.

All indications are that Marine Le Pen is incredibly popular among working-class voters. The French communist parties and the PS have neglected the concerns of the working class, allowing Marine Le Pen to win this constituency away from them (Onfray, 2011). In April 2011, polls indicated that 42 percent of the French working class supports Marine Le Pen (Mergier and Fourquet, 2011, p. 18).

Issue Co-optation Favoring the Co-optee

Marine Le Pen pointed out publicly to the press in March 2011 that one of Nicolas Sarkozys most trusted advisors prior to taking office as Interior Minister in France in January 2011, Claude Guéant, was overtly aping or imitating her. She quipped that Guéant ought to become an honorary member of the FN based on recent statements that he had made about Muslim immigration to France and considerations of French secularism (Le Point, 2011), in which he seemed to be borrowing his lines from the FN. Le Pen said that Guéant appeared to have been touched by grace with the inspired positions he was taking on these issues, with the implication being that he had been all too directly inspired by the FN.

In the days following the remarks, Pascal Perrineau, professor at the Institut dÉtudes Politiques de Paris and Director of the Center for Political Research at Sciences Po (CEVIPOF), confirmed in an interview that the UMP Interior Minister Claude Guéant had been putting out targeted messages aimed at FN voters in an attempt to recapture their focus and support for the mainstream right UMP (Me, 2011). Perrineau indicated that out of concern for the challenge to UMP support posed by the strength of Marine Le Pens polling numbers, the UMP recognized and reacted to the FN. They did so by having Guéant mimic the themes from the FN that were most appealing to the right-wing conservatives that the UMP wants to poach from the FN. Such accounts suggest that the FN is once again the co-optee, and that this is proving favorable to their legitimacy and political position.

PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS OF THE NATIONAL FRONT UNDER MARINE LE PEN: SOURCE EXPLANATORY FACTORS

Leadership Style and Strategy

Undeniably, Marine Le Pen shares common traits with her father, including charisma, populist approachability, and veiled ideology expressed in laymans terms. By all accounts she is also a savvy politician with political acumen. Still, the political brand offered up in the form of Marine Le Pens FN appears markedly different from that of her fathers party, according to many accounts. There is a new generation of activists attracted by the social discourse of Marine, according to Thierry Gourlot, head of the FN in Lorraine in an interview with Le Point (Bastuck, 2011). Gourlot joined the FN in October of 2011 after seeing Marine Le Pen speak at a public event. He noted that there were no racist remarks to be overheard in the crowd assembled around him and he took this to be an indication of a new FN. The gaffes of Jean-Marie Le Pen contributed to a certain amount of demonization and pejorative portrayals that the FN under his leadership had to struggle against. With Marine Le Pen, the opposite appears to be true. She is professional in her persona and style, measured in her speech, and adept at public speaking. A new generation of FN supporters appears to be relating to a new generation of FN leadership in Marine Le Pen (Bastuck, 2011).

Like her father, who turned to think tanks and intellectuals to reinvigorate and recast the partys ideological stance and platform positioning, Marine Le Pen turned in 2010 to the think tank created by politician and lawyer, Louis Aliot of the FN, called Ideas Nation (Idées nation) to advise her campaign (Mestre, 2011). Aliot became a vice-president of the National Front in January 2011 and is a member of the executive committee of the party. Ideas Nation held its first conference in June, with the theme The Republic Confronts Zones of Lawlessness making insecurity concerns the central topic of the conference (Mestre, 2011). The FN rhetoric in 2012 has reflected this focus as well, turning away from the identity issues that took center stage in the past and focusing more on insecurity and economics. The security policy espoused by the FN, as explained by Marine Le Pen, portrays an apocalyptic scenario for criminality and violence in neighborhoods. She said the response should be swift justice with harsh penalties whereby, action is met with immediate reaction and sanction from the first act of delinquency. She went on to say, We must rid the neighborhoods of thugs who terrorize (Mestre, 2011). She spoke also of the need for increased funding to the judiciary by as much as 25 percent in order to accommodate the increased policy-emphasis on insecurity that she advocates, which requires quick prosecution of criminal offenders and tough penalties for their crimes. Along these lines, she also mentioned urban renewal programs designed to overcome the ghettoization problem in cities associated with increased criminality.

Issue Focus and Positioning to Expand the Base

The gap has narrowed to a point of obvious overlap in the positions of the UMP and the FN on the issues of immigration and law & order. In an interview with Le Point, Philippe Bilger, the Advocate General at the Court of Appeal of Paris, said that he sees little difference between the UMP and FN on matters of policy these days (Pierre-Brossolette, 2011) and this view is widely shared among the French public. While the issue co-optation over two decades has meant that the message of the two parties has sounded strikingly similar and this is not an original observation that differentiates Marine Le Pen from her father Bilger alluded to a stylistic factor that contributes to her broadening and more mainstream appeal than seen previously with the FN. Namely, she is not demonized like her father, as he puts it. This suggests that while Jean-Marie Le Pen also attempted a catch-all strategy for the FN in the 1990s, Marine Le Pen stands better positioned to actually achieve it.

Present indications suggest that thus far the catch-all strategy has produced the desired result of winning over more supporters for the FN. In an interview in May 2011, Marine Le Pen told Le Point magazine that she has seen party membership in the FN double in size over the preceding ten months and that people from all economic classes, both genders, varied demographics, and across social milieu are turning to her and the FN with their support (Pierre-Brossolette, 2011). Public opinion barometers appear to back up her claims of a widening net of support. In a BVA/Les Echoes poll, respondents indicated that they now believe the FN is a party like the other parties in the sense of being perceived as a contender with credibility and legitimacy like that possessed by mainstream parties (Pierre-Brossolette, 2011).

Scholars who study France have attested to the catch-all claims regarding the widening base of FN support in 2011. Nonna Mayer, a political scientist at CEVIPOF, who has published widely on the subject of French voting behavior, said the following in an interview in February of 2011,

We have people from all social groups voting for the National Front, and it changes from election to election, but the two strongholds are small shopkeepers, afraid by the modernisation and globalisation on the one hand; and the working classes. Usually, whatever the election, these people define themselves as either right-wing, the majority, people who feel that the right is not tough enough; or what we call here, neither nor-ers, neither left, nor right, people, mostly working classes, who have the feeling that the little people are not listened to, that nobody cares except the National Front today. Maybe 20 years ago, they would have voted for the Communist party, but now the Communist party doesnt represent anything anymore, so they turn to the National Front [Mayer, 2011].

By all accounts, since the partys leadership transition in January 2011, Marine Le Pen has expanded the base of the FN, exceeding expectations to attract considerable media attention.

Conclusions

Marine Le Pens FN resembles that of Jean-Marie Le Pen in terms of both the lateral and source factors explored above. Similarly, both FN leaders benefitted from their context in which French mainstream parties have proven somewhat weak and relatively unpopular for nearly two decades now, apart from perhaps the period after 2002 when Sarkozys mainstream right coalition made a comeback with its tide of popularity in the form of the blue wave. Both have largely been able to use issue co-optation to their advantage, exhibiting publicly perceived ownership of key issues such as law & order and immigration. Both have exuded charisma and relatability, employing a populist style of speaking directly to the average citizen, although by many accounts Marine Le Pen gives a more polished interview or public speech than her father. In sum, the analysis above suggests that rather than being a substantial departure from the old FN, in many ways Marine Le Pen represents a continuation of the style and strategy that brought her fathers FN to a culmination point in 2002. However, one differential factor stands out: she appears to be doing it all in a way that is both qualitatively and quantitatively better than he did.

As a final cautionary note, however, the FN continues to struggle to maintain its presently successful internal balance. One semi-exogenous factor affecting the FN as it moves forward under Marine Le Pen remains the ability of her father to allow the new FN to operate independently of his influence. Stepping down as party leader in January 2011, Jean-Marie Le Pen should be a factor external to the party at this point. However, he has provided some evidence that he is not quite ready to relinquish all ideological control of the party. Following the domestic terrorist attack in Norway that killed 77 people in July 2011, Jean-Marie Le Pen used the website of the FN to speak out about racist views, calling the Norwegian government naïve in its lack of awareness of the dangers of terrorism and mass migration (Monnot, 2011). Marine Le Pen had chosen to remain noticeably silent on this issue, and her political rivals in the two French mainstream parties the UMP and PS took issue with her silence, publicly suggesting that she should have commented on the killings and condemned or challenged the remarks of her father (Le Monde, 2011a; 2011b). This incident brought a weakness of the FN to the foreground, namely the fact that the party has potentially volatile factions. The new supporters of the FN represent a generational shift in many ways, away from the dated party ideologues still obsessed with identity politics. By moving away from identity politics in her focus, Marine Le Pen has pushed to the backburner those within the FN as well as within the party elite who hold more racist and xenophobic views to be their primary political motivation. Holding together a party with sharp internal divisions may prove cumbersome.

References

Bastuck, N. (2011), Chez les nouveaux lepénistes. Le Point, 12 May. [ Links ]

Bell, D. S., Criddle, B. (2008), Presidentialism enthroned: The french presidential and parliamentary elections of April-May and June 2007. Parliamentary Affairs, 61, pp. 185-205. [ Links ]

Bergounioux, A., Evin, C., Richard, A., Sapin, M., Soulage, B. (2002), Quel renouveau pour le Parti socialiste?. Le Monde, 21 June. [ Links ]

Betz, H. (1994), Radical Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe, New York, St. Martins Press. [ Links ]

Caldwell, C. (2011), The future of the European right? Christopher Caldwell interviews Frances Marine Le Pen. The Weekly Standard, pp. 21-24, 14 March. [ Links ]

Ceccaldi, M. (2002), Personal Interview, National Front Deputy Director of Legal Affairs, Conducted at party headquarters in St. Cloud, France, 22 January 2002. [ Links ]

Cole, A. (2003), Stress, strain and stability in the French party system. in J. Evans (ed.), The French Party System, New York, Manchester University Press, pp. 11-27. [ Links ]

Davies, P. (1999), The National Front In France: Ideology, Discourse, and Power, New York, Routledge. [ Links ]

DeClair, E. (1999), Politics on the Fringe: The People, Policies and Organization of the French National Front, Durham, Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Downs, A. (1957), An Economic Theory of Democracy, New York, Harper Collins Publishers. [ Links ]

Eatwell, R. (2005), Charisma and the revival of the European extreme Right. in J. Rydgren (ed.), Movements of Exclusion. Radical Right-wing Populism in the Western World, Hauppauge, Nova Science, pp. 101-120. [ Links ]

Economist, (2003), Frances socialists against change, pp. 55, 24 May. [ Links ]

Givens, T. (2005), Voting Radical Right in Western Europe, New York, CambridgeUniversity Press. [ Links ]

Gollnisch, B. (2002), Personal Interview, National Front Party Delegate General and member of the European Parliament, Conducted at party headquarters in St. Cloud, France, 22 January. [ Links ]

Hainsworth, P. (2004), The extreme right in France: The rise and rise of Jean-Marie Le Pens Front National. Representation, 40, pp. 101-114. [ Links ]

Hainsworth, P., Mitchell, P. (2000), France: The National Front from crossroads to crossroads? Parliamentary Affairs, 53, pp. 443-56. [ Links ]

Hayward, J. (1990), Ideological change: The exhaustion of the revolutionary impetus. in P. Hall, J. Hayward, and H. Machin (eds.), Developments in French Politics, New York, St. Martins Press, pp. 15-32. [ Links ]

Knapp, A. (2004), Parties and the Party System in France: A Disconnected Democracy?, New York, Palgrave. [ Links ]

Le Monde (2011a), Attentats dOslo: Marine Le Pen refuse de condamner les propos de son père. 31 July, retrieved 15 August 2011 from http://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2011/07/31/aubry-condamne-les-propos-de-jean-marie-le-pen-sur-oslo_1554642_ 823448.html. [ Links ]

Le Monde (2011b), Norvège: PS et UMP dénoncent le silence de Marine Le Pen. 1 August, retrieved 15 August 2011 from http://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2011/08/01/norvege-segolene-royal-denonce-le-silence-de-marine-le-pen_1555031_823448.html. [ Links ]

Le Point (2011), Marine Le Pen: Guéant est touché par la grâce. 17 March, retrieved 21 May 2011 from http://www.lepoint.fr/politique/marine-le-pen-gueant-est-touche-par-la-grace-17-03-2011-1307851_20.php. [ Links ]

Mayer, N. (2011), Marine Le Pen elected to lead National Front. Transcript of an interview by Keri Phillips broadcast on ABC News radio on 16 February, retrieved 8 August 2011 from http://www.abc.net.au/rn/rearvision/stories/2011/3133960.htm. [ Links ]

Me. A. (2011), Interview with Mr. Perrineau: The reaction of Mr Le Pen is a return of the repressed. Le Monde, Politique, p. 9, 2 August. [ Links ]

Mergier, A., Fourquet J. (2011), Le point de rupture: Enquête sur les ressorts du vote FN en milieux populaires, Paris, Éditions Jean Jaurès Foundation. [ Links ]

Mestre, A. (2011), Mme Le Pen prône la tolérance zéro contre linsécurité et accable M. Sarkozy. Le Monde, Politique, p. 13, 18 June. [ Links ]

Monnot, C. (2011), Jean-Marie Le Pen juge la naïveté de la Norvège plus grave que la tuerie dOslo. Le Monde, Politique, p. 8, 31 July. [ Links ]

Noblecourt, M. (2002), La crise retardée, le Parti socialiste sattaque à sa reconstruction. Le Monde, 2 July. [ Links ]

Norris, P. (2005), Radical Right: Voters and Parties in the Electoral Marketplace, Cambridge, CambridgeUniversity Press. [ Links ]

Onfray, M. (2011), Plus personne à gauche na le souci des ouvriers ou ne les représente. Le Point, p. 60, 12 May. [ Links ]

Pedahzur, A. and Brichta, A. (2002), The Institutionalization of extreme right-wing charismatic parties: a paradox?. Party Politics, 8, pp. 31-49. [ Links ]

Pégard, C. (2002), Etat de choc: La faute á qui? Le Point, pp. 8-13, 25 April. [ Links ]

Perrineau, P. (2000). The conditions for the re-emergence of an extreme right wing in France: the National Front 1984-98. in E. Arnold (ed.), The Development of the Radical Right in France: From Boulanger to Le Pen, New York, St. Martins Press. [ Links ]

Pierre-Brossolette, S. (2011), Marine Le Pen, lattrape-tout. Le Point, p. 46-49, 12 May. [ Links ]

Platone, F. (1997), Les partis politiques en France, Toulouse, Éditions Milan. [ Links ]

Prager, M. (2002), Personal Interview, Legislative staffer for Jean Marie Bockel (Parti Socialiste), conducted at a restaurant near the legislative office building, Paris, 17 January 2002. [ Links ]

Riding, A. (2002), Jospins loss reveals a left that is losing its platform. New York Times, p. A6, 22 April. [ Links ]

Rydgren, J. (2004), The Populist Challenge: Political Protest and Ethno-Nationalist Mobilization in France, New York, Berghahn Books. [ Links ]

Safran, W. (2003), The French Polity, sixth edition, New York, Longman. [ Links ]

Schain, M. (1999), The National Front and the French party system. French Politics and Society, 17, pp. 1-16. [ Links ]

Schain, M. (2002), The impact of the French National Front on the French political system. In M. Schain, A. Zolberg and P. Hossay (eds.), Shadows over Europe: The Development and Impact of the Extreme Right in Western Europe, New York, Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Shields, J. (2011), Marine Le Pen elected to lead National Front. Transcript of an interview by Keri Phillips broadcast on ABC News radio on 16 February, retrieved 8 August 2011 from http://www.abc.net.au/rn/rearvision/stories/2011/3133960.htm (file retrieved August 8, 2011). [ Links ]

Vernet, D. (2002), Populismes dEurope. Le Monde. pp. 13-20. [ Links ]

Williams, M. (2006), The Impact of Radical Right-Wing Parties in West European Democracies, New York, Palgrave. [ Links ]

Williams, M. (2009), Kirchheimers French twist: A model of the catch-all thesis applied to the French case. Party Politics, 15, pp. 592-614. [ Links ]

Received 12-9-2011. Accepted for publication 30-10-2011.

Notas:

1 Pippa Norris (2005) and others refer to such a causal or catalytic dichotomy of factors that are internal and external to the party in terms of demand side and supply side factors.