Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.201 Lisboa out. 2011

The radical right ineurope, between slogans and voting behavior

Nicolò Conti*

* Unitelma Sapienza, University of Rome, Viale Regina Elena, 295, 00161 Rome, Italy. e-mail: nicolo.conti@unitelma.it

Abstract

The article analyzes the radical rights attitudes toward the EU focusing in particular on the level of congruence between the programmatic statements of their central offices and the voting behavior of their MEPs. It shows that although radical right parties are a source of opposition to the EU, within the EP they express their dissent by abiding by the rules of the game, voting with the opposition more than the other forces do, but also voting almost as often with the majority. The radical rights MEPs engage in the legislative process and cooperate with parties on both sides of the political spectrum more than the Eurosceptic rhetoric and statements of their central offices lead the public to believe.

Keywords: Radical right parties; attitudes; EU; Euromanifestos; MPEs.

A direita radical na Europa, entre slogans e comportamento de voto

Resumo

O artigo analisa as atitudes da direita radical em relação à UE, focando-se, em particular, no nível de congruência entre as afirmações programáticas dos seus dirigentes e o comportamento de voto dos seus membros no parlamento europeu. Demonstra que apesar de os partidos radicais de direita constituírem um foco de oposição à UE, quando no parlamento europeu expressam o seu desacordo dentro das regras do jogo, votando com a oposição mais do que as outras forças, mas votando também com a maioria quase com igual regularidade. Os grupos parlamentares inserem-se no processo legislativo e são mais colaborantes com outros partidos de toda a gama ideológica do que a retórica e as afirmações dos dirigentes centrais fazem crer.

Palavras-chave: Partidos radicais de direita; atitudes; UE; Euromanifestos; DPE.

Introduction1

Many studies show that Euroscepticism has become an ideological pillar of radical right parties. It is a theme that has acquired greater relevance within the political discourse of this area, to the point that these parties have become the main stronghold of EU-pessimism (Mudde, 2007). In particular, their political discourse has largely internalized the EU issue, making the radical right the political area where this issue has become more salient (Kriesi, 2007). In this article, I analyze the radical rights attitudes toward the EU, focusing especially on the level of congruence between the programmatic statements and the voting behavior of their MEPs. Notably, the aim of the article is to describe the problem along the following lines:

1) an analysis of the level of congruence of party positions within the programmatic supply of these parties, as well as within the voting behavior of their MEPs;

2) an analysis of the level of congruence between the political discourse of the party central office and the voting behavior of the party in public office.

It is an approach that aims at integrating several dimensions of party attitudes toward the EU examined in earlier studies, such as the dimension of the political discourse that was examined through the party manifestos for the European elections (Gabel & Hix, 2004), and of the institutional behavior of politicians that was examined through the voting behavior of MEPs (Hix et al., 2007). In sum, I will produce a description of what radical right parties say about Europe, what their MEPs do in order to translate the party rhetoric into concrete political action, and how congruent these two dimensions of the party stance on the EU are.

From the theoretical point of view, the article will contribute to understanding politics and the behavior of the radical right in different ways. First, the results of the comparative analysis will allow us to determine whether the radical right behaves cohesively enough to present the character of a real party family. Or, alternatively, it will determine whether the empirical evidence supports the argument maintained by the founder of the German Republicans Franz Schönhuber among others (in Mudde, 2007, p. 159) that a genuine European radical right does not really exist.

Second, assessing the level of congruence between the attitudes of different faces of party organization is a relevant problem that current research has just started to address (Conti, Cotta & Tavares de Almeida, 2010). Assessing the extent to which the official party stance on the EU overlaps with that of party officials holding public office is particularly meaningful for a comprehensive understanding of the broad phenomenon of party attitudes toward the EU. Recent research shows that citizens are far less pro-European than politicians (Best, Lengyel & Verzichelli, 2012). Given the gap in the support for the EU between citizens and politicians, it is indeed relevant to study whether the party central office pools together with the party in public office or whether it takes more cautious positions. In other words, does the stance of the MEPs within the European Parliament (EP) reflect the party discourse on the EU developed for usage in the electoral market? The comparison between the attitudes of the party central office and those of the MEPs presented in this article will allow us to answer this question.

The Contents of Euroscepticism: What the Radical Right Says About the EU

In order to analyze the attitudes of radical right parties toward the EU and to describe the main components of these attitudes (dissatisfaction with the defense of national interests, opposition to EU policies, protest against loss of sovereignty) I will examine the party positions on a set of specific issues. I will start my analysis with a study of party Euromanifestos, the programs that the national parties present for the EP elections. These documents provide a useful representation of the ideological structure and policy preferences of parties. Radical parties tend to have a particularly good electoral performance at the EP elections given the second-order nature of the scrutiny, and thanks to the Proportional Representation (PR) nature of the electoral system. Their visibility in these elections tends to be high and their programmatic assertiveness is consequently also high. It is important to note that Euromanifestos are usually issued by the party central office and present the overall party line for use with the party rank and file and with the electorate. Thus, these documents reflect a unitary vision of the party and do not offer much evidence of any possible intra-party division. This limitation, which is intrinsic to any manifesto analysis, is also the starting point for an interesting research question: Is a party cohesive enough in its stance on the EU? As mentioned in the introduction, this article begins to address the problem by means of a comparison between the analysis of party manifestos that I present in this section, and that of the voting behavior of the MEPs in the following section.

Given the level of complexity and the increasing number of policy areas in which the EU is involved, it seems useful to break down party attitudes across many aspects of European integration. This allows for a disentangling of party attitudes across different dimensions of the EU process and a determination of whether the same stance is confirmed across such dimensions. For this purpose I will focus the analysis on the dimensions of representation and policy. It is a research strategy that seeks to include several functional aspects of supranational integration in the analysis. In the recent past, the theoretical debate (Bartolini, 2007; Benhabib, 2002; Cotta & Isernia, 2009) as well as some empirical studies (Conti & Memoli, 2010; Hooghe, Marks, & Wilson, 2004, Hubé & Rambour, 2010; Gabel & Hix, 2004) have defined these dimensions as relevant for the analysis of the EU impact on member states and of the response of political actors to such an impact.

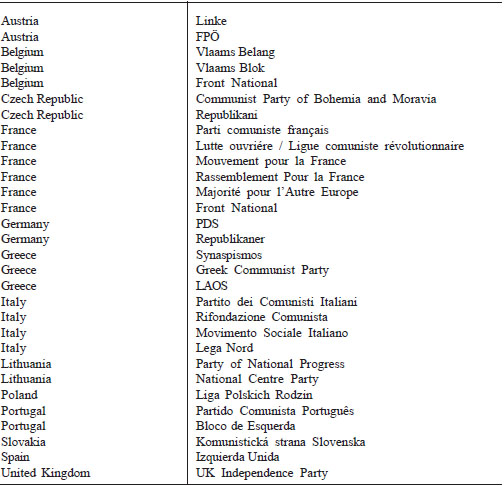

Table 1 - The coding scheme: dimensions, themes and positions in the analysis

The data base used for this part of the analysis was created by the IntUne project.2 A group of national experts coded 298 Euromanifestos3 of all political areas in 15 member states.4 Although these documents refer to the 1979-2004 period, the large majority actually refer to 1994-2004.5 One could claim that parties may have changed their attitudes over this period. In fact, this does not seem to be the case for radical parties, as the empirical analysis has already shown that a change in attitudes toward the EU can be found mainly in the moderate parties (Gabel & Hix, 2004). On the contrary, radical parties are not inclined to change their attitudes on the EU, they tend instead to be rather stable in their opposition (Szcerbiack & Taggart, 2003, 2008), which, over time, has only become more salient, especially in the case of the radical right (Kriesi, 2007). We expect, therefore, to find variations across time to be quite limited in scope. In any event, I will report these when they are deemed relevant.

The IntUne coding scheme created for the analysis of Euromanifestos allows for an accurate examination of the content regarding the EU arena, from two points of view: 1. the occurrence of EU-related themes; 2. the party positions on the EU. The coding process proceeded as follows. First, the Euromanifesto was taken as the unit of analysis. Then, coders examined whether or not a set of specific issues were mentioned within each Euromanifesto. They then coded the relevant party positions on such issues, regardless of their salience. We did not consider salience because some of our selected themes are so specific that they occupy very limited parts of the texts, while remaining very important in describing the party vision of Europe, especially in relation to issues such as sovereignty and deepening the EU. Before coding the national Euromanifestos, the coding system was tested on a standard text in English by all country experts. For the variables analyzed in the article and reported in Table 2, the tests inter-coder convergence rate in the coding exercise was 66%, a rate considered adequate by Krippendorff (2004, p. 241) for reliable content analyses.

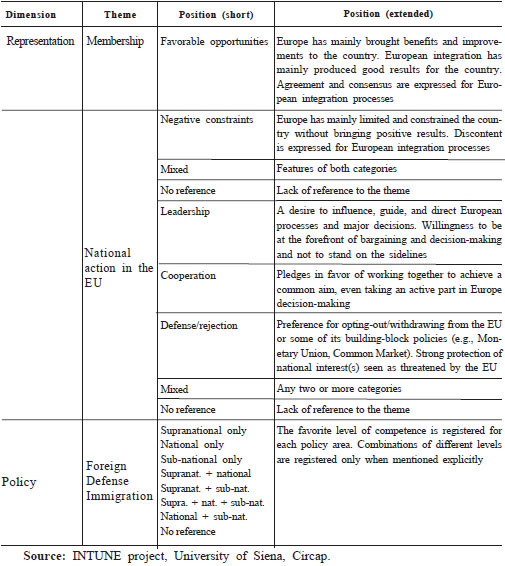

Table 2 - Euromanifestos that mention the analyzed themes (percentages)

We start the analysis with an examination of the level of occurrence of the selected themes within the Euromanifestos. In Table 2, we find evidence of the fact that, in their documents radical parties generally refer to such themes as often as (or even more often than) mainstream parties do. Certainly, the table does not contain any information about the direction of the positions expressed on the specific issues in the documents. However, it was relevant to find confirmation that the analyzed themes do play an important role in the party discourse on the EU. They are important components of the party stance on the EU. Although across parties some differences can be detected in terms of frequency of occurrence, overall, the selected themes recurred frequently in the Euromanifestos (in 51.7 to 88.8 per cent of Euromanifestos, depending on the theme). Hence, we can be confident that they represent good empirical referents for the analysis of party attitudes toward the EU, as they accurately structured the programmatic supply provided in the Euromanifestos.

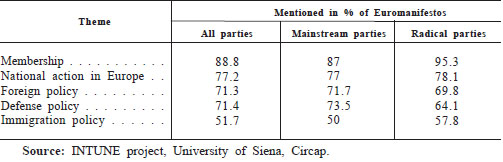

The analysis moves now to a more in-depth examination of the direction of party positions. For this purpose, I applied multinomial logistic regression models for the analysis of the content analytic variables drawn from the Euromanifestos. This technique allowed me to estimate the likelihood for radical parties to express Eurosceptical positions as compared to mainstream parties. Subsequently, within the radical party category I separated left from right. The comparison of attitudes between parties of different ideological orientations allows us to understand the phenomenon of Euroscepticism comparatively and to insert these attitudes within the broader context of inter-party competition and of contestation of the EU issue. Precisely, multinomial logistic regression models estimate the likelihood of different cases to belong to each category of the dependent variable when compared to a reference category. For example, in Table 3, the ExpB coefficient estimates the likelihood of each category of the dependent variable membership to occur compared to the reference category favorable opportunities. In other words, the model estimates how likely it is to find in the Euromanifestos (of the mainstream and radical parties respectively) no reference, a mixed, or a negative evaluation of the country membership, compared to the reference category favorable opportunities. I found that in their Euromanifestos, radical parties have an almost 11 times (ExpB=10.75) greater likelihood to represent membership as a negative constraint than to represent it as a positive opportunity. On the contrary, such likelihood is almost null (ExpB=0.2) for mainstream parties.6 In particular, I found that 70% of the Euromanifestos of the radical right (and 64.7% of those of the radical left) expressed a negative evaluation of the country membership. Consequently, the expectation of a broad Eurosceptism rooted in the radical parties is confirmed in the data.

Table 3 - Party positions on membership

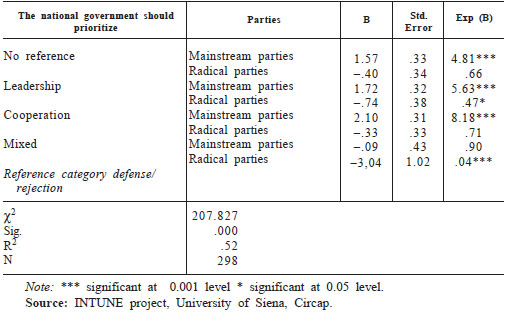

With this negative evaluation of membership on the side of radical parties comes their strong emphasis on the need for the national government to oppose decisions at the EU level that could constrain the member states. In order to find evidence of this, I analyzed how parties think the national government should behave in the EU arena. In Table 4, defense/rejection is the reference category. I found that mainstream parties are 8 times (ExpB=8.18) more likely to express a preference for a cooperative behavior, i.e., for an acquiescent conduct of the national government. Furthermore, they are over 5 times more likely (ExpB=5.63) to prefer the leadership of the national government within the EU arena, i.e., to be in favor of a voice option. In the end, as it was easy to predict, mainstream parties are divided on the assertiveness and the role that the national government should have within the EU. On the contrary, the category of radical parties is more focused on the defense/rejection solution, while the likelihood for the Euromanifestos of these parties to fall into any other category is not significant.7 However, it is important to highlight the differences in the attitudes of the two extremes. The defense/rejection category occurs in 43.3% of the Euromanifestos of radical right parties as compared to 6.7% of those of the radical left, whose most recurrent category (38.2%)8 is, instead, that of cooperation (occurring in only 6.7% of Euromanifestos of the radical right). These results show that, although Euroscepticism is deeply rooted in the radical parties under the form of a broad attitude, for instance when they evaluate country membership, when we break down the broad stance into more specific attitudes, we find that Euroscepticism is definitely more pronounced in the radical right.

Table 4 - Party positions on national action in the EU

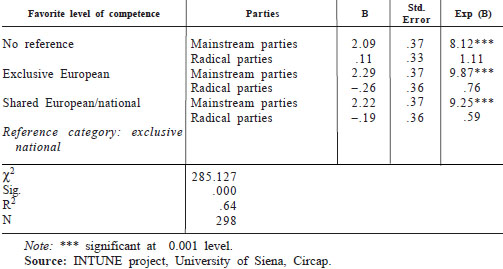

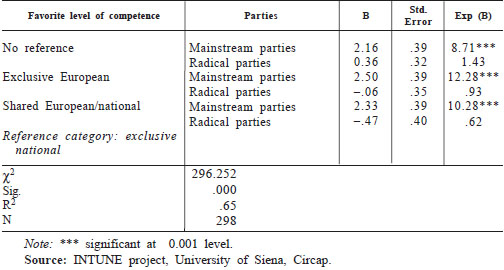

Moving the analysis to the policy dimension, we find the same pattern. In particular, we see the same tendency for attitudes toward foreign and defense policy. In Table 5, mainstream parties show a 9.9 and 9.3 times greater likelihood for the exclusive EU competence and a shared EU-national competence, respectively, as compared to the reference category of the exclusive national competence. Thus, mainstream parties are rather divided in terms of degree of involvement of the EU in foreign policy, something that could explain the difficulties in integrating the Second Pillar of the EU. However, they agree overwhelmingly on some kind of involvement of the EU, while they voice a preference for the exclusive national competence only very rarely. The same tendency can be found for defense policy (Table 6) as the preference of mainstream parties for the exclusive European competence and for the shared EU-national competence is 12.3 and 10.3 times greater than for the reference category of exclusive national competence. For both policies, values for the radical parties are, instead, not significant. The reason can be found in the dispersion of their preferences across different categories. Dispersion occurs between the radical left and radical right, as well as across countries. Overall, the preference of radical parties for the exclusive national competence exceeds that for any other option. They voice this sovereignist stance in foreign and defense policy in 27% and 25% of their Euromanifestos, respectively, without any particular distinction between left and right. However, somewhat unexpectedly, the share for the other categories is also similar. Notably, over time the radical left but not the radical right becomes more supportive of the EU competence, until a peak in 2004, when 66.6% of the Euromanifestos of the radical left supports the EU competence (either exclusive or shared) in foreign policy and 53.9% in defense policy.9

Table 5 - Party positions on foreign policy

Table 6 - Party positions on defense policy

In sum, differences between mainstream and radical parties are remarkable since the EU involvement in these two policy areas is much less popular with radical parties. However, only a minority of radical parties rejects the EU involvement in principle, while on this issue the radical left has become increasingly aligned with mainstream parties over time. In the end, the radical right is the main stronghold of opposition against the communitarization of foreign and defense policy. However, even for these parties, Euroscepticism is not absolute. Although integration of these policies deeply challenges one of the core values of the radical right, namely the defense of national sovereignty, its national components are divided on what the best level of competence is. In some countries, radical right parties support some EU competence in foreign and defense policy10 as they see the EU as a potential barrier against globalization and U.S. dominance, which they oppose more fiercely: against both forces, any national scale action would be powerless, especially from countries of small size or reduced strategic power. Ultimately, although at various degrees and certainly more to the left than to the right, the EU has acquired some legitimacy as a level of governance even within the programmatic supply of radical parties. Euroscepticism in this sphere prevails in the radical right, but as we have seen, not unanimously.

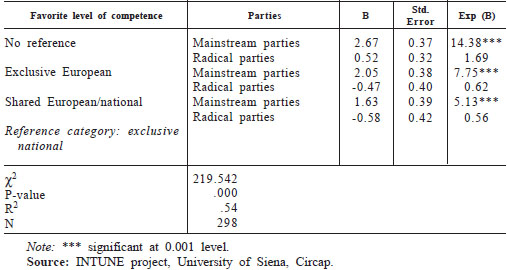

We move now to the analysis of immigration policy. On the one hand, the likelihood of a preference for the exclusive EU competence or the shared EU-national competence on the side of mainstream parties is almost 8 (ExpB=7.75) and 5 (ExpB=5.13) times greater than it is for exclusive national competence (reference category). However, a lack of reference to immigration issues is the most likely possibility for mainstream parties (ExpB=14.38). On the other hand, the preferences of radical parties are again dispersed among different categories. Even more than for foreign and defense policy, such dispersion is to be attributed mainly to the radical left. As a matter of fact, the position of radical right parties is more univocal, as 42.9% of their Euromanifestos support the exclusive national competence in immigration policy (as compared to 20.6% of the Euromanifestos of the radical left). It is evidence of the fact that radical right parties make their programmatic supply on this issue very distinctive from that of the other parties, and characterize their stance along the lines of a more openly nationalistic posture. Although fewer than half of the Euromanifestos of the radical right really favor the most nationalistic solution, the other most recurrent category is the no reference one, especially among the new member states11, while a preference for the EU involvement in the immigration policy is only residual among radical right parties.12

Table 7 - Party positions on immigration policy

To conclude this part of the analysis, we can summarize that we found confirmation of the fact that the radical right is the main stronghold of party-based Euroscepticism. However, this attitude is broad more than it is absolute, and most importantly, it is not univocal across the European countries. Although still very criticized, the EU has acquired legitimacy by radical right parties in some member states where its role as a policy-maker is relatively welcome. The very existence of the EU is therefore not questioned by these parties. The Euroscepticism of the radical right is still quite strident, especially if one compares their attitudes to those of mainstream parties and even of radical left parties whose opposition against the EU has become more nuanced over time. Still, it would be difficult to talk about a principled opposition of the radical right against the EU when parties are so divided about what role the EU should play in the European system of governance.

How Radical Right Parties Vote in the European Parliament

The article now moves to the analysis of the institutional behavior of the MEPs of the radical right. Specifically, I will examine whether they vote cohesively within the EP. As a matter of fact, in the previous section it was shown that the programmatic supply of the radical right is characterized by some common positions, as well as by some important differences. We now investigate whether these differences also translate into a diverse behavior of radical right MEPs within the EP. In addition, this part of the analysis allows us to shed light on the issue of the level of coherence existing between the protest-based rhetoric of radical right parties in the election campaign (however mitigated by specific policy positions that, as we have seen, are not so much opposed to the EU) and their institutional behavior after the elections.

For the analysis, I have selected the EP group Independence/Democracy (IND/DEM) of the 2004-2009 legislature. The group was created in 2004, when parties from the Eurosceptical Europe of Democracy and Diversities group made an alliance with some parties from the new member states. The most important parties of IND/DEM were the following13: the UK Independence Party (UKIP), the League of Polish Families, the Italian Northern League (suspended in 2006 and then expelled from the group after the scandal of the t-shirt worn by the party member Calderoli showing anti-Islamic cartoons), and the Movement for France. Additionally, some MEPs from the Czech Republic, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Sweden took part in the group. However, other important radical right parties such as the French National Front and the Vlaams Belang did not join IND/DEM, deciding instead to belong to the Non-Attached group. By the end of the legislature, especially after the expulsion of the Northern League, the group could rely on just 2.8 per cent of the seats in the EP. Definitely, this lack of unity within the EP of radical right parties provides evidence of a lack of cohesion of their intents and strategy. As a consequence, the argument of whether they could be considered a genuine party family finds negative evidence here. At the very least, these parties are not transnationally organized, as are most other party families, and this in turn creates an impediment for the establishment of greater coherence of action within this political area. This lack of transnational organization also creates a problem for the analysis undertaken in this article. Due to the dispersion of the radical right MEPs among various groups, any finding pertaining to IND/DEM only partially represents the radical right as a whole. Furthermore, the empirical referent considered in the two parts of the analysis is not identical, as the Euromanifesto data examined in the previous section referred to a larger number of radical right parties than the data on the voting behavior of the MEPs of Independence/Democracy. However, I will show that in spite of these limitations, it is still possible to produce some considerations and to advance some tentative conclusions about the phenomena under analysis.

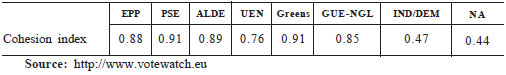

The first problem that I shall explore concerns the internal cohesion within IND/DEM. For this purpose, in Table 8 I report a measurement elaborated by Hix and Noury (2009) regarding the internal cohesion of the EP groups in the period 2004-2009 based on the roll-call votes (all data in this section are available on-line at http://www.votewatch.eu).14 It clearly emerged that within the EP context, IND/DEM was the group with lowest internal cohesion, comparatively as low as the Non-Attached group. To be more precise, their level of cohesion was about half the average level (0.8) of all party groups with the exclusion of IND/DEM and the Non-Attached.

Table 8 - Cohesion index of the EP political groups (2004-2009)

On the other extreme of the political spectrum, the European United Left/Nordic Green Left group (GUE-NGL) showed a level of internal cohesion in line with the above mentioned average. Hence, the radical right was internally divided along its national components much more than was any other group of the EP. Indeed, we need only recall that some ideological diversity also emerged in the Euromanifesto analysis, but strikingly wide divisions emerged in the way the radical right MEPs voted in the EP. It is interesting to note that the low level of internal cohesion of the IND/DEM is also revealed when we disaggregate votes by policy areas, as scores tend to be close to the overall cohesion rate:

0.5 for budgetary policy, economics, foreign and defense policy, and culture and education;

0.4 for justice and home affairs, unemployment, social policy, development, transportation, tourism, fishery, and equal opportunities;

0.3 for agriculture, environment, industry, energy, research, and internal market.

Precisely, among the parties in this group, the UKIP voted against the party line one out of three times and the League of Polish Families one out of five.15 Hence, among the larger parties that formed the group, the latter was the one that contributed more to determine the party line. However, its defection rate of one fifth should not be ignored, and it is the sign of rather undisciplined conduct and lack of leadership within the political group. Since we found an extremely low level of internal cohesion, this can not be explained by the defections of the British and Polish MEPS alone. It follows that the other MEPs of the group representing even smaller parties have all and together defected the party line more frequently.

Having established that radical right parties within the EP are not cohesive, it is now interesting to analyze how they behave vis-à-vis the other parties. One underlying characteristic of radical right parties is indeed their anti-system rhetoric. For this reason, they have alternatively been labeled as populist, extreme right, fascist, or protest-based organizations (Mudde, 2007, p. 29). Indeed, at the national level, they often reject the system from its constitutional foundations. At the same time, the system tends to exclude them; at the national level several institutional barriers such as those coming from the electoral rules have been erected in order to marginalize these parties. So, with only some exceptions and contrary to mainstream parties, radical right parties are usually rooted on the ground of the society more than they are in public office. As a consequence, they are also largely excluded from public resources consisting mostly of state financing that are instead more readily available to cartel parties (Katz & Mair, 1995). Hence, at the national level radical right parties can successfully represent themselves as standing apart from the system and their distinctiveness as a form of non-collusion and disinterestedness. They can do so especially when they criticize the state elites, one of the main threads in their rhetoric. What happens then when we shift the focus of the analysis to the EU system? Is their anti-system protest also transferred to the EU level? We found that the Euromanifestos are rich in criticism of the countrys membership in the EU (Table 3). Now we analyze whether such a broad stance also corresponds to an institutional practice of outsiders within the EP.

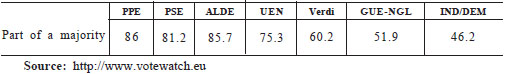

In reality, the tendency of IND/DEM, as well as of the radical left, to a participatory and even collusive behavior within the EP should not be underestimated. Although the number of times this group was part of a majority in the EP was the lowest among all party groups, the total rate (46.2 per cent) (Table 9) is still considerable, and certainly higher than what we could expect from any anti-system force. Hence, in almost half of the cases, IND/DEM was part of a parliamentary majority. To be sure, their votes only converged with large majorities composed of at least two large parties (the European Peoples Party [EPP], the European Socialist Party [PSE], or the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe [ALDE]). Therefore, their vote was not necessary to build minimum winning coalitions, and consequently their blackmail potential and coalition power remained very limited even when they joined a majority. Just as at the national level (where only few exceptions can be found in countries such as Austria and Italy), also in the EP the radical right is largely non-influential for the formation of coalitions. For this reason, it is surprising that they have voted along the lines of a parliamentary majority so often, especially when we consider that only a fraction of the votes of IND/DEM converged with those of parliamentary majorities of center-right leaning parties (either EPP, ALDE, or Union for the Europe of Nations [UEN]) and could therefore be justified on the basis of some common ideological inclinations. In most cases, the majority also included (to a greater or lesser degree) the PSE, the Greens, and the GUE-NGL. An in-depth analysis of the contents of the bills passed with the support of IND/DEM would be necessary in order to discover the motivations for their institutional behavior one that could certainly not be labeled as the behavior of outsiders. It is, however, a research goal that goes beyond the scope of the analysis presented in this article, but one that future research should consider in order to shed light on this interesting phenomenon concerning the institutional behavior of the public office of radical right parties.

Table 9 - Times when EP political groups were part of a winning majority (percentages)

Certainly, convergence with the EP majority is also due to the consensual nature of the EP, in which decisions are often the lowest common denominator agreements among the different forces that are represented in this assembly. However, even from this perspective, we can not avoid defining the strategy of the radical right in the EP as either one of voice, or one of acquiescence. As their votes converged with those of large coalitions and were therefore not necessary to form a majority, we can hypothesize that the blackmail potential of IND/DEM was really limited on those occasions, as well as their capacity to influence the final outcome in the decision-making process. Hence, their strategy should really be characterized by acquiescence more than by a real capacity to voice their preferences and force the other parties to compromise with them. In the end, it seems that radical right parties are rather maximalists on the EU in their rhetoric (although even in this respect the analysis of Euromanifestos has shown that in some countries they accept the EU as a level of governance) but they tend to exclude the most maximalist option of exit when they operate within the EU institutions. This result is also confirmed by the attendance rate (82.5%) to the plenary sessions of the EP by the MEPs of IND/DEM, a rate that is very close to the average of the other (mostly mainstream) groups (84.6%). As we have seen, a vote with the majority corresponds to this high attendance rate in almost half of the cases and a vote against (or abstention) in the remaining part. Only when they vote against the majority do they express their protest against the main groups, usually by voting with parties on the extremes of both left and right (Hagemann, 2009). It is evident that radical right parties collect votes in the European elections based on a broad Eurosceptical stance (with policy-specific positions that are sometimes not Eurosceptical to the same degree). However, once in the EP, it is important to note that they express their dissent making use of the rules of the game, voting with the opposition more than the other forces do, but voting almost as much with the majority. If these figures were known by the public at large, it would not be surprising if the protest-based electorate of these parties felt dissatisfied with their institutional conduct.

It seems that the public office of these parties is far less anti-EU than the political discourse of their central office. There may be several explanations for this behavior. On the one hand, there might be a search for legitimacy on the part of these parties. They wish to participate in the decision-making process and they wish to be considered credible coalition partners. This could be achieved more easily in an assembly such as the EP where coalitions are formed on an issue-by-issue basis, rather than by following pre-arranged coalition agreements between either the groups or the national delegations. On the other hand, radical right parties might be aware of the advantages that come with representation in the EP. They can have a public office that is often lacking at the national level where they are frequently excluded from institutional representation due to electoral rules, the impact of strategic voting in first-order elections, or the marginalization by mainstream parties. The advantages of representation in the EP are not negligible, especially for small radical parties. Notably, from a financial point of view, parties represented in the EP have access to public financing, which has become so important for the survival of parties in contemporary times (Katz & Mair, 1995; Aucante & Dézé, 2008). Such funds come directly from the EU budget, in order to allow the organizational functioning of the EP. They come from the national budget as well, in the form of ordinary contributions or electoral reimbursements of the expenses. Ultimately, either directly or indirectly, the EP is doing a great deal for the financial and organizational survival of small radical parties.

Alternatively, we could look for other non-strategic explanations of the institutional behavior of radical right MEPs. Just like any other actor who is inserted in the European decision-making system, they become gradually socialized to the practices and principles of the EU governance, through forms of interaction oriented toward consensualism, which in the long term creates a sense of trust and identification with the institution and with the system at large (Schimmelfennig, 2000). This could also explain why the radical right often takes a more pragmatic stance in the EP than the rhetoric of their central office would anticipate. None of these potential explanations can be examined in depth in this article, but certainly knowledge about the radical right, as well as about EU politics, would greatly benefit from an analysis of these possible determinants of the party conduct in the EP. In the meanwhile, although it is not yet possible to talk about a radical right in the EU that is anti-establishment but open to government, it seems that there is already enough evidence to talk about a radical right that is anti-establishment and part of the system.

Conclusions

The analysis that was carried out in this article shows that the radical right is the party block characterized by the lowest levels of internal cohesion in the whole context of European party families. This finding holds true both in the analysis of ideology that was examined through party Euromanifestos, and in that of institutional behavior carried out through data on the roll-call votes of the MEPs. The Euroscepticism of the radical right is well-known. However, after an accurate analysis, it was shown that it is discontinuous and it lacks a common vision across its national party components. If this diversity were verified not only with respect to the European issue but to other issues as well, there would be reason to question whether the radical right could be defined as a party family, or if it should instead be considered a disordered aggregation of national parties of erratic ideological positions. The article shows that the radical right in Europe is divided into a plethora of stances and policy preferences and by reciprocal enmities and political antagonism. From the analyses, it emerged that their ideological foundations, programmatic supply, and organizational features are so diverse that it even seems hard to group them under a distinctive party family name. This finding reinforces Muddes (2007) argument regarding the need to classify parties that common wisdom tends to pinpoint within the radical right with more accuracy.

Furthermore, a clear tendency toward a greater pragmatism and moderation of the MEPs emerged in the article as compared to the party programmatic announcements. Although radical right parties represent a source of opposition within the EP, they also take part in parliamentary majorities in almost the same proportion. This phenomenon shows that there is a remarkable distance between the central office and the public office of these parties, at least in terms of coherence between the statements of the former and the institutional conduct of the latter. Whether this is a conscious, or even a strategic game played by these parties, it is a question that the present article has not examined. Certainly, their conduct raises many questions that future research may address. Overall, the party public office in the EP is more institutionalized, more inserted in the legislative process, and even more collusive with the other parties of both sides of the political spectrum than the rhetoric and statements of central office leads the public to believe.

References

Aucante, Y. and A. Dézé (eds.) (2008), Les transformations des systèmes de partis dans les démocraties occidentales. La thèse du Parti de Cartel en question, Paris, Presse de Science Po. [ Links ]

Bartolini, S. (2005), Restructuring Europe: Centre Formation, SystemBuilding and Political Structuring between the Nation-state and the European Union, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Benhabib, S. (2002), The Claims of Culture: Equality and Diversity in the Global Era, Princeton, Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Best, H., Lengyel, G. and Verzichelli, L. (eds.) (2012), The Europe of Elites. A Study into the Europeanness of Europes Economic and Political Elites, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Conti, N., Cotta, M. and Almeida, P.T. de (2010) Citizenship, the EU and domestic elites. Special issue of South European Society and Politics, 15(1). [ Links ]

Conti, N. and Memoli, V. (2010), Italian parties and Europe: Problems of identity, representation and scope of governance. In Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 11(2), pp. 167-182. [ Links ]

Cotta, M. and Isernia, P. (2009), Citizens in the European polity. In C. Moury and L. de Sousa (dir.), Institutional Challenges in Post-Constitutional Europe, London, Routledge, pp. 71-94. [ Links ]

Gabel, M. J. and Hix, S. (2004), Defining the EU political space: an empirical study of the European election manifestos, 1979-1999. In G. Marks and M. Steenbergen (eds.), European Integration and Political Conflict, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 93-119. [ Links ]

Hagemann, S. (2009), Strength in numbers? an evaluation of the 2004-2009 european parliament, European policy centre issue paper no.58, brussels. [ Links ]

Hix, S., Noury. A. and Roland, G. (2007), Democratic Politics in the European Parliament, New York, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hix, S and A. Noury (2009), After enlargement: voting patterns in the sixth European parliament. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 34(2), pp. 159-174. [ Links ]

Hooghe, L., Marks, G. and Wilson, C. (2004), Does left/right structure party positions on European integration?. In G. Marks and M. Steenbergen (dir.), European Integration and Political Conflict, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 120-140. [ Links ]

Hubé, N. and Rambour, M. (2010), French political parties in campaing (1989-2004): A configurational analysis of politcal dicourses on Europe. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 11(2), pp. 146-166. [ Links ]

Katz, R.S. and Mair, P. (1995), Changing models of party organization and party democracy. The emergence of the Cartel Party. Party Politics, 1(1), pp. 5-28. [ Links ]

Kriesi, H. (2007), The role of European integration in national election campaigns. European Union Politics, 8(1), pp. 83-108. [ Links ]

Krippendorff, K. (2004), Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology, Thousand Oaks, Sage. [ Links ]

Mudde, C. (2007) Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe, New York, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Schimmelfennig, F. (2000), International socialization in the new Europe: rational action in an institutional environment. European Journal of International Relations, 6 (1), pp. 109-139. [ Links ]

Szczerbiak, A. and Taggart, P. (2003), Theorising Party-based Euro-scepticism: Problems of Definition, Measurement and Causality, Paper presented at the VIII Biannual International Conference of the European Union Studies Association, Nashville, March 27-29. [ Links ]

Szczerbiak, A. and Taggart, P. (2008), Opposing Europe, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Received 30-7-2010. Accepted for publication 16-8-2011.

Notas

1 An earlier version of the article was published as a working paper of the Institute of Advanced Studies of Vienna.

2 INTUNE (Integrated and United: A quest for Citizenship in an ever closer Europe), an Integrated Project financed by the VI Framework Programme of the European Union (CIT3-CT-2005-513421). The research in this article was also supported by the Italian National project Il processo di integrazione europea in una fase di stallo istituzionale: mutamenti nelle sfere della rappresentanza politica, dei processi decisionali e della cittadinanza sociale financed by the Ministry of Education (PRIN, 2007).

3 Among these documents there are 30 Euromanifestos of the radical right.

4 The countries included in the analysis were the following ones: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

5 In particular, only two Euromanifestos of the radical right date from 1989, the others date from 1994-2004.

6 I considered mainstream parties to be those belonging to the following party families: Christian democrats, socialists, liberals, conservatives, regionalists (with the exception of the Northern League), greens, and some other moderate parties at the suggestion of the national experts involved in the research. I categorized Communists, extreme left, nationalists and the extreme right as radical parties (see Appendix). The sample contains a larger number of Euromanifestos from the old member states, because they have participated in more EP elections, than from the new member states that have participated since 2004. It was not an aim of the article to differentiate between old and new member states, so in spite of their different representation in the sample, cases were not weighted.

7 Changing the reference category does not change the result, as radical parties have a tendency to concentrate their preference in the defense/rejection category.

8 In particular, Izquierda Unida and Synaspimos are the main advocates of this solution within the radical left.

9 The German PDS and the Greek Synaspimos were particularly in favor.

10 Among radical right parties, the MSI/National Alliance in 1994 in Italy (then coded as mainstream party in the following years), the Flemish Vlaams Belang, and the Francophone National Front in 2004 in Belgium supported the EU involvement in both policies.

11 For example, in 2004, the Lithuanian National Center Party and Party of National Progress, and the League of Polish Families did not make any reference to the issue of the favorite level of competence in immigration policy.

12 Only the Italian MSI-National Alliance in 1994 and the German Republicans in 1999-2004 supported the involvement of the EU in this policy.

13 The group ceased to exist in 2009 when some of its components united with the remnants of the Union for a Europe of Nations group to create a new group called Europe of Freedom and Democracy.

14For each vote, the group cohesion was calculated using the index of Rice: (Y-N)/(Y+N+A), where Y = nr. of votes in favor, N = nr. of votes against, and A = nr. of abstentions. The cohesion rate of each group is the mean score of all roll-call votes.

15The other parties of IND/DEM have fewer than five representatives in the group. It is not possible to calculate loyalty scores for national groups with fewer than five MEPs. A national group is made up of MEPs from the same member state who join the same European Political Group.

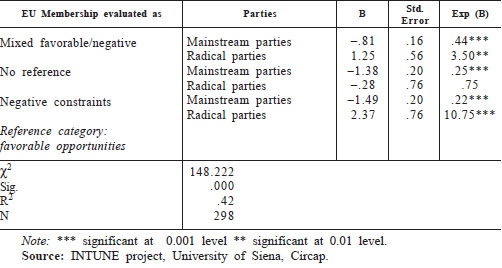

Radical parties considered in the analyses of Euromanifestos