Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social n.197 Lisboa 2010

The institutional dimension to urban governance and territorial management in the Lisbon metropolitan area

José Luís Crespo*, João Cabral*

* CIAUD, Faculdade de Arquitectura, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Rua Sá Nogueira, Pólo Universitário do Alto da Ajuda,1349-055 Lisboa, Portugal. e-mail: jcrespo@fa.utl.pt and jcabral@fa.utl.pt

Approaches to governance have been influential in the design and implementation of urban policies. The state and public administration no longer play the exclusive role, focusing now on the coordination of interests for achieving collective goals. The organisational capacities of the central/regional and local powers are, therefore, critical to urban management efficiency. The article analyses the Lisbon metropolitan area, looking into practices of planning and governance in terms of (i) the role of municipalities determining patterns of development relative to the central state and public companies; (ii) the emergence of municipal and inter-municipal institutions and companies in the management and provision of services.

Keywords: governance; territorial planning; metropolitan area; Lisbon.

A dimensão institucional da governança urbana e da gestão do território na área metropolitana de Lisboa

As abordagens da governança têm vindo a influenciar o desenho e a implementação das políticas urbanas. O Estado e a administração pública deixam de ter o papel exclusivo, concentrando-se na coordenação de interesses e procurando garantir metas colectivas. A capacidade de organização dos poderes central/regional e local é crítica para a eficácia da gestão urbana. Neste sentido, o artigo analisa práticas de planeamento e governança na área metropolitana de Lisboa em termos (i) do papel dos municípios, determinando padrões de desenvolvimento face ao papel do Estado e das empresas públicas, e (ii) da emergência de instituições municipais e inter-municipais na gestão e provisão de serviços.

Palavras-chave: governança; gestão territorial, área metropolitana; Lisboa.

Introduction

Governance is a long-standing term/concept and a still older reality (Pierre & Peters, 2000; Peters, 2002). Societies have always needed some form of orientation and guidance, leadership, and collective management. Variations in political and economic orders have produced different responses to fundamental issues relating to just how to guide and structure society and how best to meet the range of challenges resulting and generate the respective responses needed. In this sense, governance is no constant, as it tends to change to the extent that needs and values also change.

The usual responses to such questions were drafted by the state, but whatever solutions may have proven effective within one particular context soon turned out to be ineffective with the passage of time. The government/governance process represents a continuation of the joint set of policies of administrative adaptations and activities in reaction to changes in society, in terms of what is designed to represent a tailoring of the means of development and the achievement of collective goals (Peters, 2002).

The adaptative capacity of contemporary governance questions the assumptions upon which are based, and which regulate, those approaches deemed traditional, specifically as regards the centrality of state intervention and public authority in government. The notion of a single locus of sovereignty and a hierarchical structure to the governance system no longer corresponds to reality.

As a concept, governance emerges out of the shared conviction that, across various levels and degrees, the traditional structures of authority [...] failed (Kooiman, 1993, p. 251) and that the modern state is now forced into a cycle of re-legitimation. The traditional conceptualisation of government, recognising the state as the most prominent actor at play in public politics, is considered as an outdated approach for the organisation of social interactions. These perspectives on governance, instead, seek to aggregate the totality of theoretical conceptions on governing (Kooiman, 2003, p. 4) and are considered an effective process of orientation for society (Peters & Pierre, 2003, p. 2).

However, there are no replacements or generally accepted alterations to guide and structure these new assumptions and, consequently, these have become even more problematic than before, for both the academic world and practitioners.

Against this backdrop, this article seeks to discuss the concept of governance across its various facets, in terms of both meanings and perspectives. Another interpretative component relates a range of phenomena and changes taking place in society with the concept of governance itself. We then move on to emphasise those governance perspectives that have most moulded the thinkings on urban policy. Finally, for the Lisbon metropolitan area, we analyse governance and territorial management, illustrating two critical aspects: (i) the question of its role and its implications for public administration decisions at the central/regional and local levels in terms of territorial planning and development; (ii) the emergence of municipal and inter-municipal institutions and companies with responsibilities for the management of areas and services within the scope of local administrative competences, with the goal of promoting flexibility, especially contractual and institutional interaction to generate greater profitability in providing these services.

Governance: the adaptability of a concept containing various meanings and perspectives

Governance is a very loose term, an umbrella concept, sometimes badly interpreted due to the multiple meanings attributed to it (Pierre, 2005). Indeed, one reason for its popularity is its ability contrary to the more restrictive term governing/government to cover the whole range of institutions and relations involving the governing process (Peters & Pierre, 2000).

Initially, the concept was closely tied up with that of governing/government. In this limited sense, its utilisation for a long period was restricted to the juridical and constitutional field to describe the running of state affairs or the management of an institution characterised by a multiplicity of actors, where the expression government seemed excessively restrictive. More recently, a majority of authors have related the concept with distinct analytical frameworks (Stoker, 1998). It has mushroomed across the output and vocabulary of the social sciences as a term/concept in fashion in various fields: politics, economics, and international relations, among others. The ideas associated are fairly diverse even if only referring to good governance, international, European, regional, metropolitan, or urban governance, multi-level governance, vertical, and horizontal governance to mention but a few of the examples. Depending on interlocutors, their fields of activity or research or, more simply, their awareness, one or many of these possible meanings may be evoked (Borlini, 2004).

This change in the meaning of government, associated with governance, falls within the framework of new governing processes. Governance refers to self-organisation, characterised by the interdependence of inter-organisational networks, recourse to exchanges in which the rules of the game endow some autonomy in relation to the state (Rhodes, 1997).

Recently, Bevir et al. (2003, p. 45) defined governance as a change in the nature or meaning of government. Correspondingly, recent years have seen the concept break free of the shackles imposed by the aforementioned limitations to take on a broader meaning and field of application. This paradigmatic character enables its deployment across various fields. Kooiman (2003) identified no less than twelve different meanings1 (depending on the respective field of usage), with only one set of common denominators taking into consideration the main institutional spheres (the state, market, and community). This broad range of meanings becomes apparent in the way the branches of the social sciences draw on different and, on occasion, distinct interpretations (Kjaer, 2004).

The modes of socio-political governance always result from interaction between the public and the private. Interactive socio-political governance involves defining the tone and establishing the political-social conditions for the development of new interactive models that regulate through co-management, co-leadership, and co-orientation (Kooiman, 1993). Governance thus approximates the term coordination through the existence of coordinated actions dependent on contingent attitudes or institutional mechanisms for coordinating and concerting actors (Scharpf, 2001).

According to Milward (2004, p. 239), governance is a broad-reaching term (and not only governmental) concerning the conditions for creating rules for collective actions, very often including private sector actors. The essence of governance is its focus on leadership and management mechanisms (subventions, contracts, and agreements), which are not exclusively associated with either the entity or possible sanctions handed down by the government. These mechanisms or tools are deployed to connect the networks of actors operating across the different domains of public policies. One empirical issue is the extent of these operations, that is, just what autonomy do they enjoy, or are they state led. Governance means thinking about the means of orienting the economy and society, as well as the means of attaining specific collective goals in which the state plays a fundamental role, focusing on priorities and defining objectives (Peters & Pierre, 2000).

More recently, another conception portrays how networking governance creates more opportunities for individuals to participate in political decision making processes and thereby become able to build social and political capital, as well as self-governance competences (Sorensen, 2002, 2005; Sorensen & Torfing, 2003).

In Europe, in recent years, the notion of governance, as a challenge to management and coordination, was the subject of widespread debate, both scholarly and political: (i) governance taking a type of paradigmatic format, as a conceptual framework for posing a series of important questions about society but which, as this is posed in pre-theoretical terms, proves difficult to encapsulate (Stoker, 1998; Le Galès, 2003); (ii) other authors have already posited governance as a theory (Pierre & Peters, 2000; Pierre, 2000 and 2005) highlighting that while there is no complete theory of governance this does constitute an analytical framework or, at the very least, a set of criteria that define those objects worthy of study (Stoker, 1998), within a perspective on governance that moves on from the assumption of institutions fully and exclusively controlling urban management and approaching them as a variable (Pierre, 2005); (iii) in its normative dimension, governance is essentially bound up with a norm or an instrument of public utility, presented as some miraculous solution, for example, in the analysis of public policies in accordance with those management trends seeking to raise the effectiveness and efficiency of public actions and that perceives governance as a tool for broadening participation in decision making processes (Pierre, 2005); and (iv) governance from an analytical perspective framed in support of an ideological discourse and as an insight for reading the transformations in public action, in particular public territorial action contributing to the new types of leadership/orientation that have been put into practice in recent decades across various domains or territories, bringing about the (de)institutionalisation of public policy analysis through focusing on a set of actors participating in the construction and treatment of collective problems (Leresche, 2002).

Governance: relationships between the concept and the field

We now proceed to set out some hypotheses on both the development and successfulness of governance from the theoretical point of view and on the relationship between the concept and the set of phenomena it incorporates. In comparative empirical studies, the majority of interpretations are not sufficiently precise for differentiating between new forms of governance and traditional forms of government. Despite these divergences, there is a relative consensus around a certain number of core points.

There are countless studies on governance that effectively dress up mutton as lamb as many of the practices currently grouped under the governance concept were previously analysed from other perspectives, such as regulatory theories in terms of public and private partnerships, industrial districts, the study of networks, management and organisation, and the new public management (Jessop, 1998; Le Galès, 1995; Borlini, 2004).

Governance and government are sometimes approached not as distinct entities but as two poles on a continuum of different types of government. While the extreme form of government was the strong state in the era of big government (Pierre & Peters, 2000, p. 25), then the corresponding extremity in the form of governance essentially represents a self-organisation and coordination of the social actor network, in a sense of resisting government leadership and management (Rhodes, 1997). The connotation of government and governance as the extremities of some theoretical continuum is, however, unlikely to prove sufficiently sensitive for capturing changes in the form and function of governance.

Part of the recent literature on governance stresses the importance of multi-level governmental structures to the dissemination of new forms of governance. Its analytical focus is rather diffuse, concentrating primarily on the European Union (EU) level and without paying due attention to the way in which these new forms of governance are (or might be) implemented at the member state and lower levels. Pierre & Peters (2000) hold that the state is losing its role as director with control displaced to international and regional organisations, such as the EU, autonomous and municipal regions, to international corporations, non-governmental organisations, and other private or semi-private actors.

There is a close connection between the development and application of the governance concept and the social changes that have been taking place in recent decades with profound transformations impacting upon western societies. This has led to the identification of a crisis in governability across various levels of government institutions, in effect, whether at the state or municipal level, losing their capacity for action and for dealing with the ongoing transformations in society. The processes of economic globalisation, European unification, the movement toward post-Fordist economic-social relations, demographic transformations, the added complexity of societies driven by their respective fragmentation, the unpredictability of the future, the lack of connectivity between weakened political authorities and citizens, and undermining in terms of both its financial sustainability and legitimacy the capitalist welfare system all go some way to explaining the failure of traditional models of public policies. The loss of this capacity to orientate led to a conviction that the state needs to alter the culture of its civil service (Pollitt, 2000) or even delegate policies to actors beyond the state structure. Some authors conclude that both the opacity around the state (Rhodes, 1997) and the formation of networks at various levels raise the complexity characterising modern society. All these facets render it increasingly difficult for the national state to enact its role as the unique regulator of the economy and social services, and increasingly demand that means of coordination and cooperation are established between institutions, territorial levels, and differing actors (Le Galès, 2003).

There is a tendency in the political science literature to associate government with regulation, while governance is frequently seen as a demonstration of the appearance of new political instruments (Zito et al., 2003). Governance is thus characterised by the rising utilisation of non-regulatory political instruments. These are proposed, designed, and executed by non-state participants, working either in conjunction with state actors or independently. We find here the concept of governance presented as a useful tool for decision making, nominating, identifying, and, when studying a new situation, characterised by a multiplicity of regulatory forms and the fragmentation of power between the various layers that now make up the political-administrative, economic, and social reality.

Governance and urban policies

In recent years, theories on governance have shaped thinking on urban policies (Dowding, 1996; Goldsmith, 1997; Le Galès, 2006; Stoker, 1998). These approaches are primarily concerned with the coordination and merger of public and private resources, which represents the strategy adopted, to a greater or lesser extent, by local authorities across Western Europe. The governance theories seek to aggregate the totality of theoretical concepts around governing and are deemed to be an effective process for orienting and structuring a society (Kooiman, 2003; Peters & Pierre, 2003), referring to processes of regulation, coordination, and control (Rhodes, 1997), analysing processes of coordination and regulation in which the main concern is the role of the government in a governance process understood as an empirical issue (Kooiman, 1993; Rhodes, 1996 and 1997). This also incorporates all types of guidance mechanisms related to public policy processes, involving various types of actors, with a variety of actions associated with different participants and with consequences for governance (Kickert et al., 1997). Public policy is formulated and implemented through a large number of formal and informal institutions, mechanisms, and processes commonly referred to as governance (Pierre, 2000; Pierre & Peters, 2000).

In cities, especially metropolitan areas and what are designated urban regions, new configurations have emerged in the relationships between the state and local power. These alterations in the political and administrative landscape have taken on specific characteristics and dimensions, in which the problems to be resolved are so important to the public authorities that they generate fields in which new forms of public action may be tested but which depend ever more upon contractual negotiations between institutions with diverse and different statutes and purposes (Gaudin, 1999). In this institutional and political entanglement driving the major agglomerations, one of the overriding objectives of public policy is to establish scenarios for exchanging and negotiating between institutions staking a claim to legitimately holding part of the general interest and endowed with a proportion of the political resources (technical, financial, juridical, budgetary resources, etc.) essential to all public action. Planning and urban professionals and local authorities have been transformed into nodes in an institutional network. According to certain analysts, this capacity to establish inter-institutional relationships is a crucial resource in the competition between metropolitan areas. The institutionalisation of collective actions seems to represent an issue of equal or greater importance than the spatial framework of the metropolises, and thus the social, political, and economic objects are greatly fragmented.

Governance formalised a reconfiguration of the relationships between the institutions and actors participating in the production and implementation of policies applied in metropolises. This largely rests upon processes of restructuring modern states and upon the increasingly important role now attributed to non-state actors and institutions in the regulation of societies.

Within the contexts of the territorial and social fragmentation bound up with processes of internationalisation and the post-industrial nature of cities perceived within the framework of urban governance, we may encounter the opportunities and capacities for urban actors to put policies into practice, in particular for economic development, but also in terms of urban planning, through the capacity to integrate diverse social and political groups and produce shared visions around urban development.

Governance results from the types of arrangement that actors build up, developing a triple capacity for action, integration, and adhesion, which results in the capacity for representation. In this sense, a more sociological perception of urban governance is defined. On the one hand, this reflects the capacity to integrate the voicing of local interests, organisations and social groups, and on the other hand, there is the capacity for external representation, to engage in, to a greater or lesser extent, unified relationships with the market, with the state, other cities, and other levels of government.

In terms of the state, the urban governance institutions are themselves restricted by factors such as the organisation of its constitutional and legal conditions and other types of responsibilities ascribed to public organisations. Despite urban governance theories providing a new approach for comparative analyses of urban policies, recognition also needs to be given to the importance of the national context in which this urban governance is enacted. National politics remains a powerful factor for explaining various aspects of urban policies, including the urban economy, urban political conflicts, and the strategies in effect for mobilising local resources. The state continues to effectively limit local political choices, remaining the key entity in national sub-affairs (Pierre, 2000). The national state is today, more than ever, influential in determining the way in which municipal councils and regions respond to the challenges of globalisation (Harding, 1997), as well as the internationalisation of the economy with the state identified as the critical determinant in local political processes (Strom, 1996). Analysis of the organisational capacities of local power structures is essential to any understanding of urban management. This happens because these organisations are among the core participants in governing. From the governance perspective, the approach to the core questions is focused upon the role of local power in urban management (Pierre, 1999).

Governance and territorial management in metropolitan areas

These issues take on particular relevance when applied to the government and territorial planning of metropolitan areas in European Union member states associated with the imperatives of competitiveness and cohesion explicit in various community declarations and directives (see Faludi, 2006 and 2007). As locations concentrating both wealth and knowledge, as well as sources of innovation, the metropolitan areas are crucial actors in economic growth and the future prosperity of European society. They are also generally, and particularly in the cities of southern Europe, the sites of conflict between the different interests and local powers (municipalities) that tend to polarise development options that might be taken up by inter-municipal and metropolitan structures ending up controlled by the national level, losing capacities for mobilising local and regional interests. It is within this dual debate over the redefinition of competences at the local level, in terms of its interaction with transversal competences at a higher level and within contexts of metropolitan competitiveness, overlapping interests and jurisdictions, that the role of governance gains meaning and pertinence.

The question is explicitly raised in the European Green Book on Territorial Cohesion when referring to the need for cooperation so as to guarantee that EU territorial cohesion objectives are met and when considering how best to proceed with future decisions on community policies Improving territorial cohesion implies better coordination between sectoral and territorial policies and improved coherence between territorial interventions (EC, 2008).

The concept of territorial cohesion, and consequently the means of guaranteeing its policy objectives, however, are not clear, as may be seen in the results of the public debate promoted by the European Commission2.

The differing concerns of entities and institutions representing countries from the north and the south of Europe are renowned. Faludi (2006 and 2007) picked up this theme when referring to a European model of society and particularly in the case of France (but extendible to other countries within the family of Napoleonic planning) expressing concerns over a cultural dimension (in contrast to the Anglo-Saxon model) to the territory and its planning supported by a system that implies, for its efficient functioning, an appropriate level of interaction between the differing territorial scopes and levels of responsibility.

Agglomérations and pays are areas characterized by geographic, economic, cultural or social cohesion, where public and private actors can be mobilized around a territorial project (projet de territoire). There is a link with regulatory planning in that the pays are invited to formulate new-style structure plans, called Schéma du cohérence territoriale. Clearly, in French eyes, the sense of purpose generated by participation in territorial projects is important [Faludi, 2006, p. 673].

The question lies in the means to establish the conditions for this interaction to take place. In the debate over European Territorial Cohesion, the contribution submitted by the Portuguese Geography Association, itself the result of wide-reaching discussion carried out at the national level by this association, made the following appropriate statement:

Given the finding that the Portuguese legal framework is in itself sufficient, the development of new forms of governance should begin by approaching the lack of coordination between the entities responsible for each sector and between scales of intervention that still remain and that have hindered the emergence of new behaviours and the strengthening of actor participation3.

This lack of coordination between entities and jurisdictions reflects the tradition of intervention with public decision makers located at different institutional levels engaged in the same territory. The relationships between the different authorities are essentially based upon shared responsibilities and a division of competences. Meanwhile, the greater autonomy of local power in relation to the state and a European openness promoted changes. There is now a multiplication of contractual relationships between the state and local power and the development of direct relationships between local levels of power and European Union institutions. Thus, the challenge arises out of conciliating national and European priorities and local initiatives and finding new means of interrelating policies enacted across different scales.

Governance and territorial management in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area

The case of the Lisbon metropolitan area (LMA) is a paradigmatic example of national/regional relational problems, given that there is no elected and representative body at the metropolitan level as there is at the municipal level. This problem is compounded by the prevailing condition of having established a metropolitan area inheriting a non-representative system of government with the absence of a planning structure. That means there was no legal framework in effect for urbanisation processes and projects beyond those undertaken by public initiative, which were furthermore already limited in scope to local councils.

Correspondingly, the growth of Lisbon and its urban region did not happen in accordance with the regulatory models and standards of the majority of European cities. The mode of regulation structuring the interaction between urbanisation and social and economic development was, in the case of Portugal, peripheral and incomplete (Rodrigues, 1988). The concern shown regarding city planning as from the late 19th century (for example, the expansion with the construction of the Avenidas Novas) and the social state intervention in the 1940s, did not extend out to the wider and more peripheral areas of the city, nor was it then integrated into any coherent social and economic infrastructural model.

Hence, the LMA experienced urbanisation, intensely and extensively, as a response to the effective demand created by a peripheral model of industrialisation, with processes more illegal than legal, stretching out along the main axes of transport and communication, taking up large areas surrounding the traditional centres through processes allocating plots of land breaking up large estate holdings (Cabral, 2004). This process was not complemented by equivalent investment in terms of the conditions for social reproduction given the low role of internal consumption and public infrastructures for economic development.

The situation changed significantly from the end of the 1970s with the intense dynamics of urbanisation overwhelming the response capacity of the municipal planning system, representative but still incipient and without any appropriate interrelationship with the decisions handed down by the central administrative entities, in particular the public sector companies responsible for major infrastructures. What happens is not very different to the problems facing many urban regions or metropolitan areas under scenarios of development conditioned by the imperatives for interaction between decision making levels, actors, and institutions with different agendas and priorities and within which the local level is normally the weakest partner.

The relative fragility of the local level is the result of its proximity to users and citizens and a more direct dependence on market dynamics (in land and housing) contrary to the concessionaries and public service providers and higher level political bodies, less immune to conjunctural fluctuations, nevertheless remaining strongly interested in the benefits deriving from higher land values and the visibility and profile generated by viable major urban projects and infrastructural works.

Given its inherent nature defined by functional interdependencies and exchanges, the management of the LMA territory, with 19 municipalities, requires a regional administration with effective authority, competences, resources, and the legitimacy to tackle and resolve the complex problems facing the region. However, this metropolitan institution, founded in 1991, is endowed with neither the competences nor the resources, partly due to being an unelected body, and has not demonstrated the capacities necessary to deal with the challenges of metropolitan governability.

In this way, governance, given its characteristics, represents a great challenge for strategic modernisation, especially in the case of the LMA, its regions and sub-regions of extensive urban and suburban concentration, with a deficit in territorial planning, excessive state bureaucracy, a lack of coordination of the means available (public and private) and horizontal and vertical interaction, social autonomy, etc.

It is known that between putting forward a specific project/plan and actual implementation, a complex bureaucratic process has to be negotiated, with intermediary decisions, rulings, authorisations, regulations, etc., which frequently combine to induce project delays or even render it non-viable. This all takes place within a universe in which various responsible participants, the state (whether centralised, dispersed, or decentralised), civil society, and others, intervene. One of the greatest obstacles to effective governability/governance may be identified in the institutional labyrinth and overlapping competences present within any planning process. One recent study4 totalled no less than 180 public entities at work in the Lisbon region, in areas as different as territorial administration, regional development, and tourism, among many others.

The role of public administration in territorial planning and development

The results of a research project undertaken by a number of schools of the Technical University of Lisbon on the dynamics of localisation and transformation of the LMA region clarify the importance of the municipal level regarding central state decisions and investments in planning the metropolitan territory5.

This study cross-referenced two types of information: the zoning classification proposed in the different Municipal Land Use Plans (Plano Director Municipal PDM) associated with patterns of land use and the built environment registered through to 1992 (the point in time when many PDMs for LMA municipalities came into effect) and between 1992 and 2001. Land use patterns were based on the identification and evaluation of the various classes of utilisation set out in the PDMs resulting from the dominant prevailing land use types.

The existence of various different classifications for land use in LMA municipal PDMs resulted in the development of a methodology for the analysis and definition of common criteria, aggregating land use classifications with similar characteristics. This relative lack of coherence in terms of typology and zoning criteria partially stems from the temporal differences in establishing the plan and the duration of drafting, ratifying, and publishing the respective PDMs, which were produced by highly diversified teams.

The various classifications were subject to analysis and comparison as well as their respective constituent criteria. This led to the identification of a set of predominant patterns in accordance with the characteristics of land occupation practices across the LMA. This analysis focused upon an extremely complex reality and it was therefore necessary to carry out aggregations and simplifications to attain the analytical objectives.

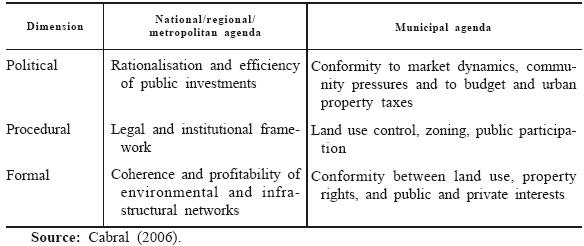

The consolidated urban environment corresponds to those territories with a planned and structured dense utilisation of the available urban space. The proposed area for urban development is standardised in all the plans, setting out large areas for urban expansion defined by the urban perimeters of the various centres, forecasting the strong urban growth identified in the map (Figure 1).

PDM spatial classifications for the LMA

[figure 1]

The areas defined in the PDM as tecido urbano consolidado (urban areas) in all municipalities is equal to around 10% of the LMA total area, with the greatest incidence attributed to municipalities on the north side of the Tagus, where this percentage rises to 13.5%. This greater density is connected to the LMAs urbanisation process, which first began around the hinterland of the national capital Lisbon supported by the first railway lines to Sintra and Cascais. Regarding the urban areas, the extent of the difference across LMA municipalities ranges from 2.4% in Alcochete, up to the 47.3% in Lisbon.

The filling out of the constructed space in urban areas reaches an average level of around 17% in the LMA, with no major disparities between municipalities. Only two cases stand out, Lisbon with the highest occupancy rate (30.3%) and, at the opposite extreme, Azambuja (4.5%), where the actual built area remains at a residual level.

The areas defined in PDMs as espaço urbanizável (urban development areas) across all municipalities account for around 5% of the total LMA without much difference between the northern and southern municipalities. The highest values, in terms of area, are in Oeiras (26.5%), Almada (38.5%), Barreiro (21.8%), and Amadora (11.4%). On the other hand, we find that the lowest percentage of urban development area is in Lisbon, which is understandable given the level of occupation and consolidation of urban areas.

The density, in terms of area, of buildings in urban development areas represents around 5% of the total LMA, again with little difference between municipalities. The distribution of occupation over the two periods displays some similarity (2.7% up to 1992 and 2.4% between 1992 and 2001). These low levels of urban occupation, recorded up to 2001, call into question the potential and forecast urban growth anticipated by the majority of the PDMs.

Furthermore, even in spaces with restrictions and limitations on construction, such as agricultural, forestry, or natural areas, we find some fairly dense incidences of construction where dispersed urbanisation has taken place.

Given these findings, an evaluation of the implementation of this generation of PDM finds, in general terms, an over-scaling of the land classified as urban/urban development areas, with spaces under this classification being far from necessary for urban expansion. This results from the excessively large PDM urban perimeters and extensive areas for urban growth punctuated by disconnected urban development projects. Thus, we encounter here an uncoordinated urban expansion in which land eligible for urban development remains vacant for long periods of time maintaining high land prices, effectively ensuring that it remains ineligible for swift intervention by the local authorities.

This overview reflects the role of administrative practises and the institutional framework regulating land use dynamics and changes. Thus, territorial transformations have been poorly influenced by planning as the tools available have proven to be non-operational, hence demonstrating the ineffectiveness of traditional rigid planning instruments.

Instead of expressing a model of territorial organisation, the PDMs reflect compromises, driven by the overlapping wishes of central administration and private interests and running counter to the objective of ensuring territorial urban coherence.

The project conclusions highlight the fact that the planning system, based on zoning, had a limited impact in the metropolitan territory. Additionally there was a lack of coordination among the different local systems. One of the aspects that potentially contributed to this lack of coordination and efficiency was the non-operational implementation of a Regional Development Plan6.

Another project conclusion was that, as one of the objectives of municipal policies is development control, these have not proven efficient, since it was primarily the infrastructures, especially road building, overseen by central authorities, that conditioned urban development, serving as guidelines for the location and development of new urban areas, equipment, and infrastructures. Within this scenario, the municipalities have played a minor role controlling urban development, which became dependent on the effectiveness of public companies, especially roads and infrastructures structuring the urban expansion process (Cabral et al., 2007).

This is the result of the confrontation between two logics of intervention that are associated with distinct agendas across two levels of intervention, the central/regional and municipal. Table 1 identifies the most significant differences between agendas with implications for urban development.

The agendas for the national/regional/metropolitan and municipal levels in territorial management and planning

[table 1]

Thus, the challenge for metropolitan governance relates to the potential synergies in institutional and operational agendas and to the capacity to foster the interrelationship between the macro-micro scales: strong institutions at the macro level and highly flexible and operational at the micro level (Portas et al., 2003, p. 39). However, the institutional and operational capacity necessary for the design and implementation of the appropriate policies raises other questions, especially in terms of ensuring compatibility between jurisdictions and the democratic legitimacy of the trans-municipal level, altering the approach and understanding of the different planning functions, capacity for innovation and additional competences (ibid, p. 208).

Flexibility in local administration management: municipal companies

The conclusions and data gathered in another recent research project on the LMA highlighted the emergence of institutions, municipal and inter-municipal companies with local government, and management responsibilities with the objective of bringing about greater flexibility and institutional interaction to ensure that services are provided on a financially viable basis. Within this context, local powers have sought to find new ways of managing public assets and interests as a general rule by handing over the direct management to more business-like regimes, seeking out partnerships with other municipalities or other public and private entities. These relationships between municipalities are marked out by broadening the systems of cooperation and exchange and by heightening competition.

The emergence of complementary municipal administrative structures only made sense in the wake of the April 1974 revolution and the 1976 Constitution, with the formalisation of a political power with autonomous administration. Thereafter, the municipalities have been taking on an increasing role in the development of their territories, gradually building up their competences across very diverse fields.

In Portugal, a process of administrative decentralisation took place in the early 1980s creating the opportunity for Portuguese municipalities to adopt a private sector approach to public services in the early 1990s7. The study produced by Crespo (2008) shows how municipal companies have swiftly become the most common form for councils to achieve a diverse range of goals. With new legislation, what was once the exception that is, companies with public capital replacing municipal departments for the provision of public services soon became the norm.

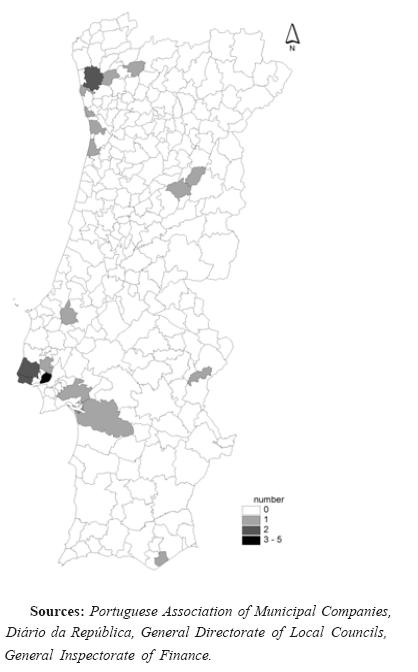

At the end of 1999, there were 25 municipal companies on mainland Portugal, with 60% of these concentrated in the two metropolitan areas of Lisbon and Porto (by 2008, this percentage had dropped by around a half). However, as from 2000, the locations of municipal companies began to expand to take in other municipalities in inland Portugal, particularly in the north of the country.

In 2001, 269 of the 308 municipalities thus, 88% of the total had direct holdings in the capital of public and private companies. Portuguese municipalities held business interests in 114 municipal and inter-municipal companies, 187 limited companies, 58 company shares, 19 banking institutions, 35 cooperatives, and 21 foundations a total of 434 entities.

Municipal Companies, Portugal (1999)

[figure 2]

According to the data available from the General Directorate of Local Authorities, in September 2005, there were 114 municipal and inter-municipal companies. Despite it being legally possible to found municipal companies since 1998, in fact, it was only in 2000 that numbers increased rapidly, with the formation of 31 companies (27.2% of a total of 114 companies). In 2001, there was a slight slowdown (28 new companies), however, in conjunction with the previous year, this two year period accounts for the formation of around 52% of existing companies.

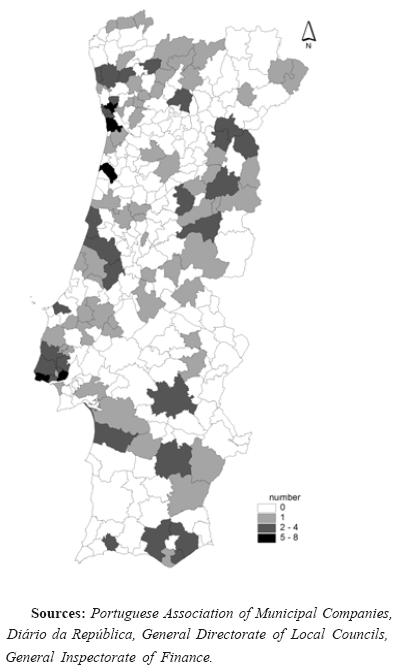

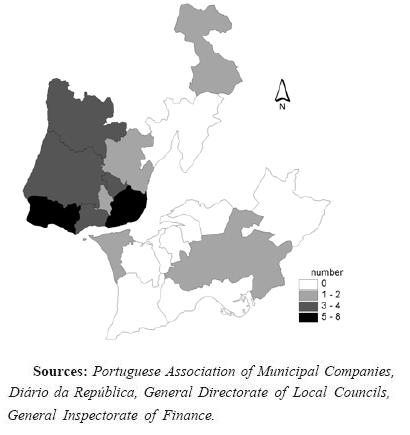

In August 2008, there were 167 municipal companies on mainland Portugal of which 43% were located in the metropolitan areas of Lisbon and Porto and in the main Portuguese cities corresponding to areas of greatest population. There is no location pattern to these municipal companies, dispersed across the country, except a slightly greater percentage in the north of the country (Figure 3).

Municipal Companies, Portugal (2008)

[figure 3]

Regarding a classification of the services provided by municipal companies, they are primarily linked to sport, recreation, and leisure (27%), culture (20%), tourism (15%), and housing (4%). The idea of municipalities handing over municipal services to municipal companies did not have widespread impact, as shown by the reduced importance of solid waste disposal, water supply, and sanitation companies. Municipal companies are mainly associated with the management and maintenance of infrastructures (swimming pools and theatre, amongst others), particularly in the municipalities outside the main urban areas.

In late 1999, 60% of these municipal companies were concentrated in the two metropolitan areas of Lisbon and Porto (in 2008, this percentage dropped by about half) with 44% located in the Lisbon metropolitan area.

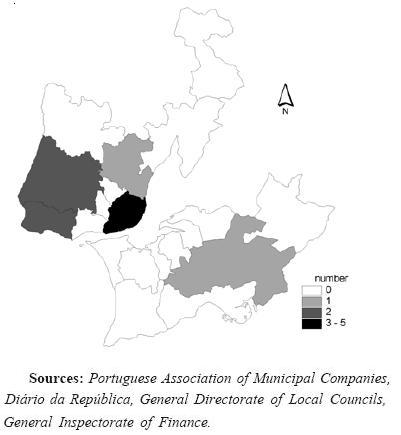

Municipal Companies, LMA (1999)

[figure 4]

Municipal Companies, LMA (2008)

[figure 5]

As mentioned above, both nationally and in the LMA, the creation and expansion of municipal companies is associated with the 1988 legislation, resulting in the greatest surge in LMA municipal companies dating to 2000 and 2001. The greatest concentration of municipal companies is in the capital, the municipality of Lisbon, where the density and diversity of problems is more acute, thus driving the need for new forms of management. The areas of intervention of municipal companies differ across the country but the most common are road transport and infrastructures (Crespo, 2008).

The reasons leading to local councils opting to set up a municipal company are not always apparent. Above all, there seem to be casuistic reasons of a political nature8 with personal attitudes guiding the choice in favour of one model or another, particularly when the entities are set up resulting from the direct initiative of the local authority. The municipal companies may also be established as a type of cloaked privatisation of municipal services. In practice, in the majority of cases, setting up municipal companies has meant little more than a transfer of competences of municipal services or departments along with their respective employees, which does not always result in their subsequent abolition.

The juridical status of municipal companies may represent an alternative to direct public management, and this delegated management may result in levels of efficiency equivalent to the private sector. However, this should in no way be perceived as a unique solution for the modernisation of local public services, as there remain countless opportunities for such modernisation to be carried out through the introduction of quality systems into public services. Another observation resulting from the information gathered enables us to state that it is still too early to provide any evaluation of the performance of this solution, especially in comparison with other public management models. For example, the question of the pricing of the services provided is a crucial factor in the decision chosen as regards the different management. In some municipal companies, the tariffs stay above average in comparison with neighbouring municipalities, while in other situations the reverse holds true (Silva, 2000).

Conclusions

The prevalence of typologies in governance studies reveals a broad spectrum of configurations. The governance without government approach argues that the direction of society on different levels increasingly depends on the interaction of networks of public and private sector actors that are to a large extent beyond the influence and control of central states (Rhodes, 1996 and 1997). Another approach accepts a central state that retains general primacy in core processes (Gilpin, 2001). A third view promotes a more participative style of government, although this does not mean a less powerful government even if in its nominal function through the concept of steering the state is restricted to subordinate positions (Kooiman, 2003). Hence, the differentiation between government and governance remains somewhat ambiguous, as there are those who affirm that the management of a particular community is a responsibility for all members, groups and sectors (Kooiman, 1999) while for others there is a certain susceptibility to absorb governance into conventional aspects of governing. Governance may be inclusive to the extent that it dilutes the border between the two concepts (government/governance).

The changes in the styles of governing involve corresponding changes to the instruments deployed as well as the makeup of the governing class. The changes in the content and targets for government are the clearest transformations. This change in solutions to basic issues became evident during the 1980s and 1990s in the majority of western European and North American countries, under neo-liberal ideas on the role of the state, with a significant reduction in public sector activities.

The governing of territories, traditionally led by the public powers in a centralised and normative fashion, has undergone accelerated mutations induced by the very evolution of society. Indeed, this new role raises serious challenges to the way central administration is internally organised and how it articulates with its surroundings and in terms of restructuring and cooperation, promoting an organisational culture based on dialogue and the surrender of old bureaucratic instruments for control and communication.

Responding to the challenges of contemporary regional (and metropolitan) governance is a necessary condition for the success of the Lisbon 2020 Regional Strategy9. However, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of the impact of socio-political processes on the governance of territories in general and to define a framework for institutional interaction in accordance with the administrative and regional civil society realities, as demonstrated by the study on the role of the different levels of intervention in LMA urban transformations, in particular.

The challenges to public power require the development and putting into practice of new institutional means of intervention. This extends far beyond the replacement of classic modes of public action and political control to include the integration of new procedures, producing new knowledge, and organising the services differently in order to ensure the effective management of public affairs. The emerging role of municipal and inter-municipal companies in the LMA illustrates these trends representing new perspectives on territorial management.

We should above all emphasise that public action should be based upon the alignment of all partners to the territorial project. This involves establishing procedures fostering exchanges between all parties, tackling shared problems, progressively building a consensus, and putting forward proposals for decision making. Evaluation equally represents a tool of the utmost importance. When effective, this may bring about a better response to the rising complexity of urban politics, strengthen the transparency of public action, inform the opinions of citizens, and promote democratic debate.

The notion of governance definitively opened up a field of research that is far from being exhaustively explored. The adaptation of the means of public regulation has continued to undergo change since the beginning of this century. The vocabulary is constantly being enriched with new terms, bringing about the renewal of mental frameworks for an understanding of emerging phenomena. Governance is no longer exclusively or even primarily a mere instrument for strategy, having become an end in itself, a concept for change, and an autonomous doctrine for the practice of modernisation.

References

Bevir, M., Rhodes, R. A. W. & Weller, P. (2003), Comparative governance: prospects and lessons. Public Administration, 81(1), pp. 191-210.

Borlini, B. (2004), Governance e Governance Urbana: Analisi e Definizione del Concetto. (http://www.sociologia.unical.it/ais2004/papers/borlini%20paper.pdf).

Cabral, J. (2004), A inovação nas políticas urbanas Modelos de regulação e sistemas de governança. GeoINova , 10, pp. 33-54. [ Links ]

Cabral, J. (2006), Urban development and municipal planning in urban regions learning from diverse planning and governance cultures and systems. Address to the WPSC-06 World Planning Schools Congress, Mexico City, 15 July.

Cabral, J., Morgado, S., Crespo, J. & Coelho, C. (2007), Urbanisation trends and urban planning in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. In M. Pereira (ed.), A Portrait of State-of-the-Art Research at the Technical University of Lisbon, Dordrecht, Springer, pp. 557-572.

Commission of the European Communities (2008), Green paper on territorial cohesion turning territorial diversity into strength, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg.

Crespo, J. (2008), Urban management in a governance context. The municipal companies in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. Address to the XI EURA Conference Learning Cities in a Knowledge Based Society, Milan, 9-11 October.

Dowding, K. (1996), Public choice and local governance. In D. King & G. Stoker (ed.), Rethinking Local Democracy, London, Macmillan, pp. 50-66.

Faludi, A. (2006), From European spatial development to territorial cohesion policy. Regional Studies, 40(6), pp. 667-678.

Faludi, A. (2007), The European model of society. In A. Faludi (ed.), Territorial Cohesion and the European Model of Society, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, pp. 1-22.

Gaudin, J.-P. (1999), Gouverner par contrat: laction publique en question, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po.

Gilpin, R. (2001), Global Political Economy: Understanding the International Economic Order, Princeton, University Press.

Goldsmith, M. (1997), Changing patterns of local government. ECPR News, 9, pp. 6-7.

Harding, A. (1997), Urban regimes in a Europe of the cities?. European Urban and Regional Studies, 4, pp. 291-314.

Jessop, B. (1998), The rise of governance and the risks of failure: The case of economic development. International Social Science Journal, 50, pp. 29-45.

Kickert, W. et al. (1997), Managing Complex Networks: Strategies for the Public Sector, London, Sage.

Kjaer, A. (2004), Governance. Key Concepts, Cambridge, Policy Press.

Kooiman, J. (1993), Modern Governance: New Government-Society Interactions, London, Sage.

Kooiman, J. (2003), Governing as Governance, London, Sage.

Le Galès, P. (1995), Du gouvernment des villes à la gouvernance urbaine. Revue Française de Science Politique, 45(1), pp. 57-95.

Le Galès, P. (2003), Le retour des villes européennes: sociétés urbaines, mondialisation, gouvernement et gouvernance, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po.

Le Galès, P. (2006), Gouvernement et gouvernance des territoires, Paris, La Documentation Française.

Leresch, J.-P. (2002), Gouvernance locale, coopération et légitimité. Le cas suisse dans une perspective comparée, Paris, Pedone.

Milward, B. (2004), The Potential and Problems of Democratic Network Governance. Democratic Network Governance, Copenhagen, Centre for Democratic Network Governance.

Peters, B. G. (2002), Governance: a garbage can perspective. Political Science Series, Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna, pp. 1-23.

Peters, B. G. & Pierre, J. (2000), Citizens versus the new public manager. The problem of mutual empowerment. Administration & Society, 32(1), pp. 9-28.

Peters, B. G. & Pierre, J. (2003), Handbook of Public Administration, London, Sage.

Pierre, J. (1999), Models of urban governance. The institutional dimension of urban politics. Urban Affairs Review, 34(3), pp. 372-396.

Pierre, J. (2000), Debating Governance: Authority, Steering, and Democracy, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Pierre, J. (2005), Comparative urban governance. Uncovering complex causalities. Urban Affairs Review, 40(4), pp. 446-462.

Pierre, J. & Peters, B. G. (2000), Governance, Politics and the State, Basingstoke, Macmillan.

Pollitt, C. (2000), Is the emperor in his underwear? An analysis of the impacts of public management reform. Public Management, 2(2), pp. 181-199.

Portas, N., Domingues, A. & Cabral, J. (2003), Políticas Urbanas Tendências, Estratégias e Oportunidades, Lisbon, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

Rhodes, R. A. W. (1996), The new governance: governing without government. Policy Studies, xliv, pp. 652-667.

Rhodes, R. A. W. (1997), Understanding Governance: Policy Network, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability, Berkshire, Open University Press.

Rodrigues, M. J. (1988), O Sistema de Emprego em Portugal, Lisbon, Dom Quixote.

Scharpf, F. (2001), Notes toward a theory of multilevel governing in Europe. Scandinavian Political Studies, 24(1), pp. 1-26.

Silva, C. (2000), Empresas municipais Um exemplo de inovação em gestão urbana. Cadernos Municipais Revista de Acção Regional e Local, xiv (69/70), pp. 13-20. [ Links ]

Sorensen, E. (2002), Democratic theory and network governance. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 24(4), pp. 693-720.

Sorensen, E. (2005), Metagovernance: the changing role of politicians in processes of democratic governance. The American Review of Public Administration, 36(1), pp. 98-114.

Sorensen, E. & Torfing, J. (2003), Network politics, political capital, and democracy. International Journal of Public Administration, 26(6), pp. 609-634.

Stoker, G. (1998), Cinq propositions pour une théorie de la gouvernance. Revue international des Sciences Sociales, 155, pp. 19-30.

Strom, E. (1996), In search of the growth coalition: American urban theories and the redevelopment of Berlin. Urban Affairs Review, 31, pp. 455-481.

Zito, A. et al. (2003), The rise of new policy instruments in comparative perspective: Has governance eclipsed government?. Political Studies, 53(3), pp. 477-496.

Notes

1 Minimum state, corporative governance, new public management, good governance, socio-cybernetic governance, self-organising networks, resource management-self-regulating societies, global governance, economic governance, governance and governability, European governance-multi-level governance, participative governance.

2 http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/consultation/terco/contrib_en.htm.

3 http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/consultation/terco/pdf/4_organisation/134_1_apg_pt.pdf

4 http://www.gestaoestrategica.ccdr-lvt.pt/1056/estrategia-regional:-lisboa-2020.htm

5 Project Totta/UTL/01(2004-2008) Dinâmicas de Localização, Transformação do Território e Novas Centralidades na Área Metropolitana de Lisboa: que papel para as políticas públicas? Project financed by the College of Integrated Studies - TUL with the participation of four Technical University of Lisbon Clara Mendes (FA) (coord.), Romana Xerez (coord. ISCSP), Manuel Brandão Alves (coord. ISEG CIRIUS), Fernando Nunes da Silva (coord. IST CESUR) and João Cabral (coord. FA).

6 At the LMA, tenuous steps have been taken in terms of governance, which are reflected in the relationship established between the CCDR-LVT and the municipal authorities, and specifically in the implementation of cooperation protocols that were agreed based upon the Regional Development Plan PROT-AML guidelines and their transposition into territorial planning instruments, especially the PDMs.

7 After various attempts, with a range of legislative packages for establishing a legal framework for the founding of municipal companies, Law no. 58/98 was approved enabling such entities to be set up (Silva, 2000). This legal framework was revised with the enactment of Law 53-F/2006. The legislation passed under these auspices provided scope for councils to participate in different management models: Associações de Municípios (Municipal Associations), Áreas Metropolitanas e Comunidades Urbanas (Metropolitan and Community Urban Areas), Fundações Municipais (Municipal Foundations), Sociedades Anónimas (Limited Companies), whether by shares or cooperatives, while Municipal Companies proved to be the most common option.

8 As shown in Figures 4 and 5, municipal companies are concentrated among the municipalities on the north bank of the LMA. Municipalities on the south bank are almost exclusively left wing in outlook (Communist Party) contrary to the north bank in which parties of the centre-left/centre (Socialist Party and Social Democrat Party) predominate. It would seem that it is above all casuistic reasons of a political nature that influence and structure the implementation of new forms of municipal management.

9 http://www.gestaoestrategica.ccdr-lvt.pt/1056/estrategia-regional:-lisboa-2020.htm